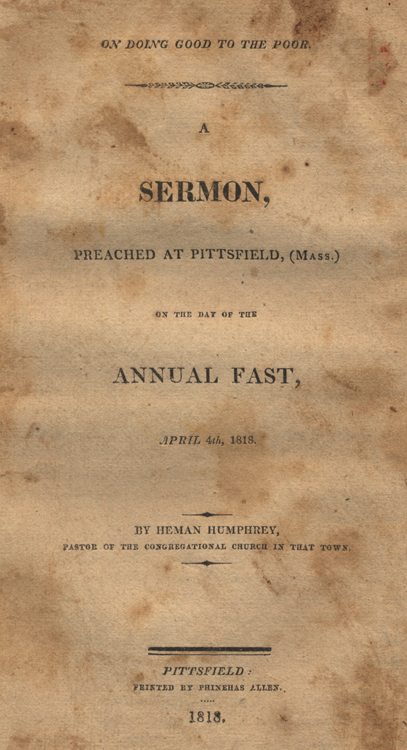

Heman Humphrey (1779-1861) graduated from Yale in 1805. He was minister of the Congregational church in Fairfield, CT (1807-1817) and a church in Pittsfield (1817-1823). Humphrey also was president of Amherst College from 1823-1845. This fast day sermon was preached by Humphrey in Massachusetts in 1818.

A

SERMON,

PREACHED AT PITTSFIELD, (Mass.)

ON THE DAY OF THE

ANNUAL FAST,

APRIL 4TH, 1818.

BY HEMAN HUMPHREY,

PASTOR OF THE CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH IN THAT TOWN.

For ye have the poor with you always, and whensoever ye will ye may do them good: but me ye have not always.

The disciples of our blessed Lord drew upon themselves this sharp rebuke, by charging Mary with having wasted a very precious and costly box of ointment, which she had just poured upon his head. They regarded it as wantonly thrown away, whereas it might have been sold for a large sum, and distributed, to great advantage, among the poor. How many of the disciples united in this complaint, against the pious and afflicted Mary, we are not informed: but no one appears to have been so much disturbed as Judas. None of the company, he would fain have it believed, felt so much for the suffering of the indigent, as himself. Why was not this ointment sold for three hundred pence and given to the poor? This he said, not that he cared for the poor, but because he was a thief, and had the bag, and bare what was put therein. The motives of the rest were good, though their indignation was entirely out of place; but Judas was influenced by the basest of passions.

Far was it from the mind of Christ, to discourage liberality to the poor. They were the objects of his tender compassion. In his human nature, and as a poor man, he sympathized with them in their privations. He strongly enjoined upon his followers the giving of alms, as an essential evidence of love to himself; and this Christian duty is clearly implied, in the very reproof which we are now considering. The poor ye have with you always, and whensoever ye will ye may do them good: but me ye have not always. As if he said, Let the poor, by all means, share in your bounty. They are always with you, and may be relieved at any time; but I am about to be taken away from you. I must die for your sins upon the cross, and the time draweth near. Whatever is done for me, must be done speedily. This act of Mary is, therefore, a well timed testimony of her love and gratitude. She hath wrought a good work upon me. She is come aforehand to anoint my body to the burying.

This view of the text may serve to correct the mistakes of some, and to expose the covetousness of others, in regard to religious charities. It fully justifies those earnest and pressing calls, which are multiplying upon us, for aid, in evangelizing the world. The missionary cause is the cause of Christ, and he now regards every pious sacrifice, for the advancement of his kingdom, as a testimony of love to himself. As it was, however, when Mary anointed his head and washed his feet, so it is, even in this enlightened age of Christian benevolence. Some who stand by, are filled with indignation. They severely blame those, who cast their gifts into the treasury of the Lord. They regard all that is done for Christ, as no better than thrown away; and too many, there is reason to fear, like Judas, express the deepest concern for the poor, merely to hide their covetousness. The truth is, they care as little in their hearts for the poor, as for Christ; but they must invent some plausible excuse for withholding their offerings from the Lord; and not content with shutting their own hands, must complain of the prodigality of those pious women, who, like Mary, come forward, to testify their love for the Saviour. But, me thinks, I hear a voice from the excellent glory. Let them alone, they have wrought a good work upon me.

It is not my intention, however, to give you a missionary sermon on this occasion. I have another important object in view. Our text brings directly before us an interesting class of the community, whose wants and sufferings have, I am happy to find, recently excited strong public, as well as private commiseration. Nor, I hope, will the discussion, on which I am about to enter, be thought unappropriate to the present season of humiliation, fasting and prayer. “Is not this the fast, saith the Lord, that I have chosen, to loose the bands of wickedness, to undo the heavy burdens, and to let the oppressed go free, and that ye break every yoke? Is it not to deal thy bread to the hungry, and that thou bring the poor, that are cast out, to thy house? When thou seest the naked, that thou cover him: and that thou hide not thyself from thine own flesh?” If such are the duties which we owe to the oppressed and the indigent, when we fast and afflict our souls before God, no subject can be more appropriate this day, than the one which I have chosen. Ye have the poor with you always, and whensoever ye will ye may do them good.

In looking round upon these pitiable objects—visiting their cheerless abodes, listening to their complaints, and thinking of their privations, many anxious inquiries croud upon the benevolent mind. What can be done for their immediate relief? How were they reduced to this state of suffering and dependence? Is their poverty unavoidable and incurable? Might not some of them, at least, be put in a way to maintain themselves? What public provision ought to be made for their support? What should be the measure of my private benefactions? How much, how often, and to whom am I bound to give? Is there not some danger of increasing the evils of poverty, by the very means which are employed to relieve it? Does not the known liberality of a town, or a neighborhood, unhappily operate, in too many instances, as a premium upon idleness and profligacy? Is it not a fact, that some of the best meant efforts to cure the disease, serve only to spread the infection?

Such are the queries, which I doubt not, every week and every day, perplex the minds of thousands, whose ears are ever open to the cry of the poor and the forsaken; whose hearts devise, and whose hands execute liberal things.

If God should enable me, satisfactorily, to answer any of these questions; to throw but a little light upon the path of duty, and to excite proper dispositions towards the poor, in your minds and my own, I shall not have labored in vain.

In the further prosecution of my design, I shall

I. Consider the fact, specified by our Lord in the text. Ye have the poor with you always.

II. Point out some of the most common and alarming causes of poverty, in this country, particularly among ourselves.

III. Propose various methods of mitigating these evils, or of bettering the condition of the poor. And,

IV. Suggest motives and encouragements for a speedy, united and persevering course of measures, for the accomplishment of this great object.

I. Let us attend to the fact stated in our text, Ye have the poor with you always. This is a matter of universal experience and observation. It has been so from the beginning. History furnishes not a solitary exception, in any age or quarter of the world. Neither fertility of soil, nor healthfulness of climate, nor profusion of wealth, nor progress of science, nor encouragements to industry, nor legal provisions, nor penal statutes, nor charitable institutions, nor private munificence, have been found adequate to banish the evils and miseries of pauperism, from any country. On the contrary, poverty has sometimes made the most alarming progress, where the rewards of industry have been most liberal, and where the amplest provision has been made for its relief. The adventurous and enterprising spirit of modern voyagers and travelers has discovered new Islands and strange people, but which of them has found the Utopia, where poverty has no dwelling-place, where want claims no relief?

Look where you will, at the present moment, and you will find pauperism in many of its distressful and appalling forms. The great empires of the east, swarm with a degraded and beggarly population. Most of the large cities, on the continent of Europe, are filled with paupers, and besieged by squalid and clamorous hordes of mendicants. Ireland is overrun by the same unhappy description of human beings. And in England, it is estimated, that one million, five hundred forty-eight thousand four hundred, or more than one ninth of the whole population, are entirely, or partly supported by the poor rates. Nor can we, in this highly favoured land of liberty and plenty, boast of our exemption from the miseries and claims of poverty. Increasing multitudes, in our cities and large towns, are miserably dependent on the aids of charity, for their daily subsistence; and even in the country, we have the poor always with us. We meet them every where in our little excursions, and are almost every day besieged by their importunities.

Of the number and wants of the poor in this town, I can form no comparative estimate, between the present and former years: but it is agreed, on all hands, that the increase of pauperism, in our country at large, far out runs its increasing population; and I have reason to believe, that Pittsfield cannot be excepted from this remark. The expenses of supporting the poor in this place, are said to be steadily advancing.

Now what, my brethren, is the conclusion to which these alarming facts should lead us? Not surely to this, that the poor are to be utterly forsaken and forgotten. Nor to this, that every thing that is contributed for their relief, is worse than thrown away. Much less, are we to sit down in despair, concluding that poverty is a sort of malignant epidemic, which must and will continue to spread, in spite of every effort and precaution, till the great mass of our people shall become incurably diseased. Much may be done to alleviate present sufferings, and to mitigate, if we cannot wholly cure the distemper. With this hope and this purpose in view, it is our present business,

II. To ascertain, if we can, the causes of a calamity, at once so distressful and so threatening, that we may the better judge what remedies and preventives are necessary.

It might, on some accounts, be an interesting speculation, to go over the ground, with those English and Scotch writers, who have, within a few years past, discussed this subject with singular ability, in reference to their own country. But many of their wisest and profoundest speculations are irrelevant to our circumstances. The alarming increase of the evil in question, among ourselves, cannot, as in Great-Britain, be ascribed to the decay of manufactures; to the enormous burdens of taxation; nor to the want of sufficient territory, to afford scope for the enterprise of an increasing population. Leaving these points, therefore, to be settled by those foreign champions, who may choose to range themselves on the one side or the other, let us confine our attention to this rising western empire, the legitimate field of our present inquiries. In pursuing this course, however, let us not refuse to be instructed, by the operation of those general laws and principles, which have had time for a more ample development, on the other side of the Atlantic.

Were I called to address an audience, in one of our great cities, on the subject before us, I should not hesitate to number among the causes of this mighty drawback upon their prosperity, lewdness, in all its fearful and horrible resorts; and gambling, in all its forms, of cards, dice, billiards, wheels of fortune, lotteries and pawnbrokers. Nor should I think it right to pass unnoticed those packed cargoes of human flesh and blood, under the name of emigrants, which the cupidity of unprincipled men has lured from foreign countries, and disgorged upon our shores, without a shilling to support them in a strange land.

Happily, the wasting operation of these causes is chiefly confined within comparatively narrow limits. That they operate with some effect, more or less obviously, to a great extent, cannot indeed be questioned; but they are not the great and prominent causes of pauperism in New-England. It is our present business to inquire what these causes are. And,

1. In this highly favoured section of the United States of America, some are placed upon the list of paupers by unavoidable necessity. In this class we may reckon, from time to time, a considerable number of sober, prudent, temperate, industrious men, who, in the course of business; by the fluctuations of trade; by the failure or dishonesty of debtors; by the ravages of floods and fire, and by storms at sea, have been reduced, with large and helpless families, to extreme indigence.

Other persons, belonging to the same class are reduced by long continued and expensive sickness; by lameness, blindness, palsy, or other adverse providences.—While they had strength and ability to labour, they were industrious, frugal and comfortable. But every means of self-support is now cut off. What they had, in better days, laid up of their hard earnings, they have been obliged to expend, and now they must look to the opening hand of charity, as their only earthly resource.

Others again, who were barely able, by industry and good management, to keep themselves off from the town, while their strength lasted, unavoidably become chargeable in their old age. While some look to their children for support, in similar circumstances, alas! Nor sons nor daughters have they. These props have fallen one after another, and mingled with their native dust. The aged and desolate widow, struggled hard and struggled long, and suffered much, before a whisper of complaint escaped from her lips. But the decays of nature, the progress of infirmities, could not be hindered nor retarded. She was constrained to yield, and is now an interesting and helpless pensioner upon public or private bounty.

Now all those, who belong to the class which has been mentioned, I call the virtuous and respectable poor. To such, poverty is no disgrace. They have done what they could. They are still willing to do every thing in their power, for their own support. They have, therefore, the strongest claims upon the public, and upon our private charities. To let them suffer for want of necessaries, is cruel; and if this neglect should at any time be chargeable upon us, God will not hold us guiltless.

2. A partial want of capacity is, in some cases, the cause of extreme indigence. Men are not formed alike. While the calculations of some are always sagacious and profitable, others have not what is called the faculty of setting themselves to work, or of turning any thing to advantage. Every step they take is in a down-hill course. Their intentions are good, and they improve their talent as well, perhaps as their prosperous neighbours. But their talent is small. They are always in a state of dependence. Now, we may lament this. We may complain of these people. We may insist that they might do better. But it becomes us to pause a moment, and answer the Apostle’s question, “Who maketh thee to differ from another, and what hast thou which thou hast not received?” Surely those who are thus deficient in natural capacity, are objects of universal compassion, and are entitled to a comfortable maintenance, when from this cause alone, they are reduced to want.

3. Many, in the providence of God, are rendered incapable of labour, and even of self-preservation, by insanity. Of all human calamities, this is the most dreadful, the most appalling. Hunger, cold, watching; the distress of a fever; the pain of a broken bone; the loss of limbs, of sight, of hearing; the persecution of enemies; the treachery of friends; the walls and fetters of a prison: any, or all of these sufferings taken together, are not worthy to be compared with the loss of reason.—“The spirit of a man will sustain his infirmity; but a wounded spirit, and may it not be added, a distracted mind, who can bear?” Have you ever, my friends, heard the ravings of a maniac, and the clanking of his chains? Have you seen the distortions of his countenance; the hurried wildness of his eye; the frightful disorder of an immortal mind in ruins? What would you not rather be, than that object of terror and compassion, even if the wealth of the kingdoms was pledged for your support, and the humane efforts of thousands were constantly employed in your behalf?

What, then, think you, must be the condition of the distracted, who have no parents, or children, or brothers, or sisters, or friends, to watch over them, or even to supply them with food and raiment! O, what yearnings of compassion should we feel for such? How freely should we contribute for their support! What pains should we take to render their situation, in all respects, as comfortable as the nature of the case will permit. Let us, for a moment, if we can endure the thought, place our souls in their souls’ stead. What are the duties which we feel that our fellow-men would owe to us, if God should take away our reason, and cast us poor, friendless, distracted, upon their charity? “All things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them; for this is the law and the prophets.”

4. Some are reduced to extreme want, by their prodigality. They might have saved enough from their patrimony, or from their earnings, to have defrayed the expenses of sickness, and to have made them comfortable, if not independent, in old age. But having enough for the present, they were regardless of the future. They spent their substance in riotous living. They wasted the bounties of providence, fondly imagining, that “to-morrow should be as this day, and still more abundant.” But their resources were soon exhausted. While they were eating, and drinking, and making merry, and saying “soul, thou hast much goods laid up for many years,” poverty stood watching at the door. The sheriff was not far behind. Suddenly, houses, lands, goods, every thing passed into other hands; and the late prodigal possessors are now upon the town, supported in part, by those whose property they have wasted; by creditors, whom their prodigality has cruelly defrauded.

5. Pride sends its thousands to the alms-house every year. The foolish desire of imitating the wealthy, in their dress, in their entertainments, in their equipage, in their pleasures, proves the ruin of multitudes, who might always have enough and to spare, by living within their means. Their destruction is, that they cannot bear to be out-done. They must have as many parties, and as many dishes, and as costly apparel, as their more opulent neighbours. And to support all this, they are obliged to live beyond their income. They encroach upon their capital. They run themselves in debt. They mortgage their estates. Bankruptcy stares them in the face. Still, perhaps, they might retrieve their affairs. But their pride will not permit them to retrench their expences. Appearances must be kept up, as long as possible. At length the baseless fabric falls, or rather vanishes. There is nothing left of all this magnificence. Dreadful a the thought is, the poor-house must, in many cases, be their refuge, their only refuge.

Nor let it be supposed, that this destructive emulation is confined to the class immediately below the most wealthy. It prevails among all classes. Those who are sensible that they can never rival the first, are apt still to aim higher than they can afford; and in this way, not a few of the lower classes ar added to the list of paupers.

6. Idleness covers multitudes with rags, and reduces hem to extreme poverty. God has put the means of competency within their reach: he has given them health and strength. By the sweat of their brow they might eat their bread; but they set themselves to counteract the decree of heaven. They are the sluggards who will not plough by reason of the cold. What they possess is wasted for want of care. Every thing indicates neglect, and presages ruin.

“I went by the field of the slothful and by the vineyard of the man void of understanding; and lo! It was all grown over with thorns, and nettles had covered the face thereof, and the stone wall thereof was broken down. Then I saw and considered it well, I looked upon it and received instruction. Yet a little sleep, a little slumber, a little folding of the hands to sleep: So shall thy poverty come as one that travelleth, and thy want as an armed man.” But,

7. Intemperance is by far the greatest and the most horrible of all the causes of pauperism, in this country. If other vices slay their thousands, this slays its tens of thousands. It is the overflowing source of that mighty flood, or rather it is that fiery deluge itself, which threatens to sweep away all that is valuable to man. There can be no question, that it sends crowds to hell every year, while it also consigns an incredible multitude of bloated masses of pollution, and of broken-hearted wives and helpless children, to rags and beggary. The extent of its ravages would exceed all credence, were we not furnished with facts and estimates, which cannot be controverted. I have room only to exhibit the following.

In the fore part of 1816, it was stated in the report of the Moral Society of Portland, that out of 85 persons, supported at the work-house, in that town, 71 became paupers, in consequence of intemperance; being five-sixths of the whole number: and that out of 118, who were supplied at their own houses, more than half were of that character.

Again: In the winter of 1817, alarmed by the rapid increase of pauperism, the citizens of New-York appointed a very respectable committee, to inquire into the state of want and misery among the poor in that city, and to devise some plan to prevent, as far as possible, a recurrence and increase of these evils. A part of the report of this committee, is in the following words.

“If we recur to the state of the poor, from year to year, for ten years past, we find that they have yearly increased, greatly beyond the regular increase of population. At the present period, there is reason to believe, from information received from the visiting committees in the several wards, that 15,000 men, women and children, equal to one-seventh of the whole population of our city, have been supported by public or private bounty and munificence.

“In viewing this deplorable state of human misery, the committee have diligently attended to an examination of the causes which have produced such dire effects. And after the most mature and deliberate reflection, they are satisfied, that the most prominent and alarming cause, is the free and inordinate use of spirituous liquors. To this cause alone, may be fairly attributed seven eighths of the misery and distress among the poor the present winter; one sixteenth to the want of employment, owing to the present distressing state of trade and commerce; and the remaining portion, to circumstances difficult to enumerate, and which possibly could not be avoided.” Think of this!

But one sixteenth part of the poverty of a great commercial city, and that, too, during a period of peculiar embarrassment, owing to want of employment, and seven eighths to intemperate drinking! What a picture! And what would be the probable result, if similar inquiries were made in all our great cities and towns; if they were extended to every section of our country; prosecuted through all the wards of our alms-houses, and carried into all those abodes of poverty, whose tenants are partially dependant upon charity for their subsistence? Would not the result be calculated to fill the hardest heart with pity, and the stoutest heart with dismay? Let the inquiry, my brethren, be made among yourselves. I am a stranger to most of those, who are maintained at the public expense, or who depend on your private bounty. I am ignorant of their history, and of the causes by which they have been reduced. But I strongly suspect, that intemperance has contributed far more than any other single cause, to crowd your poor-house, and to multiply objects of suffering and compassion around you. I am now,

III. To propose remedies, to point out ways and means of bettering the condition of the poor. This is, by far, the most difficult part of our subject. It is incomparably easier to trace the calamities of human life back to their causes, than to cure them. Thus a neighbor is desperately sick, and we are at no loss, perhaps, to account for it; but the disease may baffle all the skill of the ablest physicians. Thus a man has kindled a slow fire in his own vitals, and we know when and where he did it; but how shall it be extinguished, and how shall others be most effectually guarded against this horrible species of self-murder? Thus, also, we see the poor; they are with us always; we hear their complaints; we know their wants; we can trace their downward progress from competency, perhaps from independence, to forsaken grey hairs and helpless infirmity.

But of all the problems which have exercised the ingenuity of great statesmen and distinguished philanthropists, in modern times, this appears to be the most intricate:—What are the best means of managing existing poverty, and what the surest preventives of pauperism? Human industry, and genius, and perseverance, have accomplished a thousand wonders. The circumference of this great globe has been measured. The phenomena of tides, and of winds also, to a great extend, have been explained. The great law of gravitation, which binds the Universe together, is now well understood. The distances, magnitudes and motions of the sun and his attendant worlds, have been ascertained, by the infallible rules of Geometry. Fire, and air, and water, and light, have been decomposed. A mild and certain preventive of the small pox, that terrible scourge of former ages, has been discovered. But who, after all the alarm that the increasing demands of poverty have recently produced, both in Great-Britain and our own country; who, after all the anxious thought which has been bestowed on the problem, and with the help of all that has been written up to this moment; who can pretend to be a perfect master of the subject? Who can point us, with a sure and steady aim, to the cheapest and most benevolent means of relieving present want, and of saving future generations from the burdens and sufferings of pauperism?

Have we then nothing further to do, in this great cause of humanity? Must we sit down in despair? Must all the fond desires and hopes of Christian philanthropy be given to the winds?

God forbid, that we should yield to this unchristian despondency. If we cannot accomplish all that is desirable , we may yet do something. If we should fail of satisfying our own minds, on every point, we may possibly gain more than we anticipate, and more than enough to pay for our trouble. Though we should not be able to strike out a single new path, who knows but we may improve some of the old ones? Let us do what we can, though much should be left for more enlightened minds to finish. Let us proceed as far as possible, and while we rest there, to gain new strength, let us “thank God and take courage.”

In theorizing on the subject before us, even wise and good men have often mistaken first principles; and hence the disappointment of their fondest hopes; hence the failure of their best endeavours to mitigate the evils of pauperism. They have not taken man as he is, a fallen depraved creature; naturally proud, indolent, evil and unthankful; but as he should be, holy, humble, industrious, conscientiously disposed to do every thing in his power to maintain himself, and thankful for the smallest favours.

It was once pretty generally supposed, and is still believed by many, that the existing ills of poverty might be cured, and the increase of it prevented, by generously and promptly feeding and clothing it. On this subject, men reason thus:—Here is a certain number of paupers and vagrant beggars, to be wholly maintained; and here are so many other poor people, to be supported, in part, out of the funds of charity. Now let us make our estimates accordingly, and then promptly follow them, with the necessary public and private appropriations. Let us generously feed and clothe the destitute, without discrimination. In this way we shall at once make up a given deficiency. We shall excite the gratitude of all whom we relieve. Our bounty will doubtless operate as a stimulus to future industry, by which many, who are now dependant, will hereafter maintain themselves; or, upon the most unfavourable calculation, should a burden equal to the present still remain, it will not, in the ordinary course of things, be augmented.

Such is the theory: but what is the testimony of facts? This seemingly benevolent plan has been tried, for a long course of years, and upon a great scale, in one of the most enlightened portions of the globe. It has also been tried, effectually, in many other places. But it has utterly disappointed the hopes and doings of charity. Many a well-fed beggar has, by proclaiming his success in the ears of the idle and unprincipled, induced ten men to embark in the same nefarious speculation. Many a charitable fund has operated as a premium upon improvidence and vice.

Many a soup-house has, to the sore disappointment of benevolence, proved a most efficient recruiting post for pauperism. The demands of poverty, in the city and in the country, have steadily increased. To meet these demands, charity has opened her hand wider, and still wider; and thus has she gone on, giving and hoping, till the poor rates in England, alone, amount to the enormous sum of seven millions of pounds, besides all her immense public and private charities: and till, within the space of eleven years, no less than 5000,000 of her citizens were added to the list of paupers!

The same result, though not so alarming in extent, has been experienced in many parts of our own country. It is now pretty well agreed, both at home and abroad, that benevolence has been all this while employed in a feeding a consumption; in throwing oil upon the fire which she would fain extinguish; and that if other means of cure cannot be found out, the case is hopeless.

Now, in this lamentable failure, there is nothing but what may be accounted for upon obvious principles.—Man, by the fall, lost the image of his Maker. He is totally depraved. Reason and conscience are dethroned and enslaved by passion and appetite. Restless as he is, labour and business are extremely irksome. Indolence and vice are his favourite elements. If he can gain a subsistence, however scanty and precarious, without the sweat of his brow, he will not work. It requires strong motives, and even pressing necessities, to rouse him to action; to make him industrious and frugal. I lay it down as a well established maxim, that no part of human industry is spontaneous. It is all the effect of habit, principle and necessity. Take any number of human beings you please, in a state of nature, and not one of them will betake himself to any regular and laborious employment, so long as he an subsist without it. Who ever heard of an industrious savage?

If you would raise up a generation of sots, and beggars, and banditti, try the experiment in your own families. Leave them to the impulse of their inclinations. Let them do as much and as little as they please. Ply them with no motives; employ m=no means to make them industrious. Let them never feel the stimulus of necessity; and where, a few years hence, would be your enterprising young men; your highly cultivated and productive fields; your trade, your domestic peace, you schools and your religion? Alas! How soon would idleness, profligacy, ignorance and barbarism demolish and sweep away all the memorials of virtue, intelligence and general prosperity. Take, then, but this single view of human nature along with you in the present investigation. Apply the remarks which have just been made, to the case in hand. First, make every allowance for the power of habit, the sense of shame and the influence of principle upon the minds of men, and how many still, if they find they can be maintained, or but half maintained, in idleness and tippling, will deliberately throw themselves and families upon your hands. Nor will the evil stop here. Make the poverty of such people honourable, or even tolerable, by your benefactions, and multitudes, who have hitherto supported themselves, will follow an example so congenial to human depravity.

Increase your charities, augment your gifts, and you add fuel to the fire. The calls of real distress will multiply faster around you, than you can possibly furnish means to relieve them. Establish a permanent charitable fund, to any amount; put half the property of the town into that fund to-morrow, and you will soon find more than enough, of an intemperate, starving and ragged population, to swallow up the income.

Such, my brethren, is human nature; and in all our plans for ameliorating the condition of the poor, we must take men as they are, and try to make them what they should be. A raging fever is not to be cured by stimulants. Poverty is not to be bribed away by costly and repeated presents. If you would cure the disease, you must have recourse to other means. You must purge out the morbid humors, and impart a new tone to the system. If you would prevent the further spread of pauperism, you must remove the causes of contagion.

With these things in view, let your attention be directed first, to the adult poor; secondly, to their children; and thirdly, to those great religious and moral preventives of needless poverty, which alone can stay the plague.

1. Let your humane attention be diverted to the adult poor. They are with you always, and whensoever ye will ye may do them good. Study to fulfill this duty in the largest sense. Endeavour to lay the foundation for their future comfort and usefulness, as well as to supply their present necessities; to make them respect themselves; to do good to their souls, as well as to their bodies.

The adult poor may be divided into three classes, viz. vagrant beggars, resident paupers, or persons who have formally thrown themselves upon the public, and a large class, who depend much on the occasional aids of charity.

It is a subject of general complaint in most of our towns, that they are exceedingly infested with vagrant beggars; most of whom are excessively filthy, clamorous, impudent and unthankful; and the question is, How ought these miserable objects to be treated? My answer is, generally, with frowns and a flat denial. This may sound harsh; but it is deliberately, and I hope kindly spoken. Experience has proved, over and over, a thousand times, that most of these disgusting fragments of humanity are arrant impostors. It is their trade to deceive the credulous, and to subsist upon the earnings of industry. They “will not work,” and therefore, “neither should they eat.” By feeding and clothing, and occasionally giving them money, you not only encourage them to continue their depredations upon society; but you inflict a lasting injury upon themselves. Where a beggar happens to have some shame and conscience still lingering about him, at the commencement of his career, these uncomfortable companions will soon be wholly discarded. And when all self-respect, when all regard for character is gone, what can you look for, from a depraved creature like man? What, but that he will “wax worse and worse,” will soon become the vilest of the vile?

Taking human nature as it is, we might safely pronounce vagrant beggary to be one of the most effective schools of immorality that ever was encouraged, even if experience and observation had not taught mankind a syllable on the subject. But a thousand facts, drawn from the history of mendacity, in various countries, might be adduced, to prove more than it could otherwise have entered into the heart of man to conceive. A few only will be given, as specimens, chiefly from Count Rumford’s interesting view of street-beggary, as it existed, about thirty years ago, in the principality of Bavaria.

“The number of itinerant beggars,” he says, “of both sexes, and all ages, as well foreigners as natives, who strolled about the country in all directions, levying contributions from the industrious inhabitants; stealing and robbing, and leading a life of indolence and the most shameless debauchery, was quite incredible. So numerous were the swarms of beggars in all the great towns, and particularly in the capital; so great their impudence, and so persevering their importunity, that it was almost impossible to cross the streets, without being attacked and absolutely forced to satisfy their clamorous demands.—These beggars not only infested all the streets, public walks and public places; but they even made a practice of going into private houses, where they never failed to steal whatever fell in their way.

“In short, these detestable vermin swarmed every where; and not only their impudence and clamorous importunity were without any bounds; but they had recourse to the most diabolical arts, and the most horrid crimes, in the prosecution of their infamous trade. Young children were stolen from their parents by these wretches, and their eyes put out, or their tender limbs broken and distorted, in order, by exposing them thus maimed, to excite the pity and commiseration of the public.

“Some of these monsters were so void of all feeling, as to expose even their own children, naked and almost starved, in the streets, in order that by their cries and unaffected expressions of distress, they might move those who passed by to pity and relieve them; and in order to make them act their part more naturally, they were unmercifully beaten when they came home, by their inhuman parents, if they did not bring with them a certain sum, which they were ordered to collect.”

Similar impositions and cruelties, we may well suppose, have elsewhere marked the ravages of this “overflowing scourge,” on the continent of Europe. To a most astonishing length has the predatory system of which I am now complaining, been carried in England, especially in and about the metropolis. To an amazing height has the audacity of the vilest miscreants proceeded, under the cloak of extreme poverty. It appears, from the report of a select Committee of the House of Commons, appointed to investigate the causes and extent of pauperism, that hundreds of hale and sturdy beggars, infest the streets of the capital, and occupy all the approaches to it by day; and that they have places of rendezvous in the environs, to which they repair at night, to make their report, and to riot and fatten on their ill-gotten spoils. Can the demoralizing tendency of practices like these, admit of a single doubt? If the grand object were to furnish victims for the gallows and tenants for the state-prisons; to train men to theft, robbery, murder, rape and blasphemy, could any more promising school of violence, pollution and blood be countenanced and patronized in any community?

I trust, brethren, that scourging and maiming helpless children, have not, as yet, attended the progress of mendacity in this enlightened and highly favoured country. But who can pronounce, with confidence, that these horrible enormities have not been practiced even here? Human nature is every where the same; and there is no philosophical truth more firmly established than this, that like causes produce like effects. If the system has not yet had time to develop all its haggard and diabolical features, in the United States, it is surely and steadily tending to the fullest maturity of sin and suffering.

Who does not know, that most of those loathsome, strolling wretches who infest our towns, are addicted to lying, swearing, drunkenness and theft. How many of them seem to take it for granted, that whatever you possess is theirs, and most outrageously abuse you, in your own houses, if you venture to deny them. How many of these insufferable drones and impostors have you found intoxicated, with the very money which you had given them to procure a night’s lodging at the public house. How often have they profanely assailed you with quotations from scripture, and dreadful imprecations of divine vengeance, when you have thought it your duty to send them away empty. Which of you would trust one of them alone, for a moment, in a room where you have any thing valuable that can be taken away? And are such impositions and abuses as these to be tolerated? Can we justify ourselves before God, in squandering upon these impious vagabonds what ought to be given away in real charity? No; let the harpies find, that what they get costs much more than it is worth. Make their nefarious trade as disgraceful and unprofitable as possible, and you will soon be freed from their impertinence. Let the same course be pursued every where, and I hesitate not to say, that it must produce a great blessing to the vagrants themselves. It will drive most of them to labour for their own support; and thus, while their best good is promoted, the public will be relieved from a most unreasonable burden. In the mean time, the few who are really incapable of self-support, will find their way to almshouses and other asylums, where they will, in general, be made far more comfortable than they are, or can be, in their present vagrant course of life.

Upon the whole, I am constrained, brethren, to give it as my deliberate opinion, that more than nine tenths of all that is bestowed upon itinerant beggars, in the shape of charity, is far worse than thrown away. It goes to feed a nest of vipers. It fearfully increases the evil which it is intended to relieve.

But here, benevolence may ask, what then ought to be done? Shall all these miserable beings be spurned from every door, and left to starve in the streets? No, my brethren, far from it. Your laws have made ample provision for their support; and under some of the best regulations, I believe, that human wisdom has ever devised. They have, in the first place, ordered to be built, in every county, “a house of correction, to be used and employed for the keeping, correcting and setting to work of rogues, vagabonds, common beggars, and other idle, disorderly and lewd persons.” To carry the provisions of the statute into effect, every justice of the peace is expressly authorized “to commit to the said houses of correction, all rogues, vagabonds and idle persons, going about in any town, or place, begging; also, common drunkards, and such as neglect their calling or employment; misspend what they earn, and do not provide for themselves and for the support of their families.”

Let every vagrant beggar, then, be reported to the nearest justice of the peace, and sent away immediately to the house of correction, where, if able, he may be compelled to labour for his own support. This course might be attended with some little inconvenience at first; but it would, I am persuaded, be the most effectual, and, in its operation, the most benevolent course that can be taken with common beggars. If any doubt, however, should arise in your minds, whether the stranger applying for charitable aid, ought to be ranked with such, direct him to the Selectmen of the town; and if, upon inquiry, they find him a proper object of their attention, let him be provided for as a state pauper. This would have a surprising effect. Not one in twenty would ever apply to the fathers of the town; for vagrants, of all men, hate the trouble of substantiating their claims, by any higher evidence, than their own declarations. Few of them are deficient in natural sagacity; and many are gifted with extraordinary shrewdness. They soon learn where they can prosecute their trade to the best advantage, and with the fewest embarrassments. Let half a dozen of them find that nothing can be obtained with an application to the Selectmen, and nearly the whole tribe will soon abandon any town, as a theatre wholly unfit for their operations.

2. The claims and wants of that class of the adult poor which I call resident paupers, next demand your attention. These, it is agreed on all hands, must be taken care of. They must be sheltered, and fed, and clothed. But how, where and under what regulations, are questions of considerable moment. The laws of this Commonwealth hold all the rateable property of each town solemnly pledged for the support of its own poor. Whether this is the best mode of providing the necessary funds, I shall not stop to inquire. It has, I am aware, recently been questioned by some very able writers. But we must take the law as it is; and perhaps it could not be altered for the better. It certainly manifests a very benevolent concern for those who cannot maintain themselves.

In providing for adult paupers, you should endeavour, as far as practicable, to make a distinction between the virtuous poor, and those of a contrary character; and to unite comfort, economy, reformation and prevention in your system.

There is no where, perhaps, a greater difference of character, than among paupers. The dependence of some, or rather the cause of it, is their deepest guilt and shame. They are self-destroyed. They have, in a sense, cut off their own hands. They have thrown their property into the fire, or what is far worse, have cast it into the bottomless gulf of intemperance. Now reason and religion seem alike to require, that a difference should be made between the precious and the vile. I think, my brethren, you will feel no hesitation in saying, that the sober and the virtuous are entitled to more aid, and deeper commiseration, than the victims of prodigality, idleness and still more shameful vices.

It may be difficult, perhaps, to hit upon the best mode of making those discriminations, at which I have just hinted; and it may be found more difficult to unite comfort, economy, reformation and prevention, in the management of pauperism. But I shall venture to suggest a few thoughts, for your serious consideration. And here my views accord so entirely with the provisions of admirable statute of this Commonwealth, passed in January, 1789, that I shall offer no apology, for making it the basis of my present remarks.

The act, in question, begins by empowering towns, either separately or conjointly, as may be most convenient, to erect work-houses within their respective limits, and to appoint overseers, whose duty it shall be, to order and manage these establishments, by making all reasonable and necessary by-laws, appointing masters, and committing all such persons as the law contemplates. The persons so liable, are thus described in the seventh section of the act. “All poor and indigent persons, that are maintained by, or receive alms from the town; also all persons, able of body to work, and not having estate, or means, otherwise to maintain themselves, who refuse, or neglect so to do, live a dissolute and vagrant life, and exercise no ordinary calling, or lawful business, sufficient to gain an honest livelihood, and such as spend their time and property in public houses, to the neglect of their proper business, or by otherwise misspending what they earn, to the impoverishment of themselves and their families.”

The statute then proceeds to enjoin the providing of all the requisite materials, tools and implements, for the use of those who may be sent to these work-houses; and explicitly requires, that all who are able to work, shall be kept diligently employed in labour, during their continuance there.

Here then, brethren, is a system prepared to your hands, and can you frame a better? If not, let a convenient house, with a small farm attached to the premises, be built, or purchased, at the expence of the town. Let every thing about the establishment be neat and comfortable. Let economy be studied, in the construction of rooms, stoves and fire-places. Let materials and implements be provided, so that all who have strength to do any thing, may be employed, either within doors or out. Let the establishment be placed under the immediate care of a discreet, humane, and if possible, religious man, with a liberal and definite compensation. Let him be instructed to take particular care of the sick, the aged and the infirm; and to require every person to do what he can for his own support. This is an essential part of the system. It is no kindness to the poor, to maintain them in idleness. It is injustice to the public; and is, moreover, a toleration which will inevitably increase your burdens, by inviting idlers to your alms-house, as a refuge from the sweat of industry.

In order to save all unnecessary expence, let the strictest economy reign through the whole establishment.—Let it be practiced in the purchase of provisions and fuel; in various experiments, to ascertain how the greatest quantity of nutritious and palatable food can be furnished, at the lowest price, and how it can be prepared at the smallest expence of fuel. This, you must be sensible, is not the place for more particular details. Let those who wish to pursue these hints, consult Count Rumford’s admirable economical essays, which are replete with entertainment and instruction.

Let the industrious and well disposed in your alms-house, receive every encouragement that the institution will permit: let all means of intoxication be religiously withheld from the intemperate. Let your establishment be a house of correction and restraint for the bad, while it affords a comfortable asylum for the deserving. Let it, also, as far as practicable, be made a school of moral and religious improvement. Fail not to furnish every apartment with bibles and tracts. Require all who are able, regularly to attend public worship. Let your clergyman consider them as a part of his charge; let him visit them often, and give them such religious instructions and advice as may be suited to their characters and circumstances. Let private Christians, also, as they have opportunity, labour for the spiritual good of these their indigent neighbours and acquaintance.

Perhaps the expences of such an establishment, including purchase money, might, for a few of the first years, be greater, than if the poor were annually and publicly cheapened under the hammer; though even this is questionable. But sure I am, that within a moderate period, the system would commend itself to the public, as the cheapest, and in all respects the best, that has yet been tried. It has been adopted, in all its essential parts, by many towns in this and a neighbouring State, and has been productive of the best effects. Let the example be followed here; let this admirable system have time to display its happy results, and I am persuaded it would effect a clear annual saving to this town of more than one thousand dollars.

The third class of adult poor, is made up of such as are not nominally upon the list of paupers; but still depend, more or less, upon charity for subsistence. With respect to these, the question of duty is oftentimes exceedingly perplexing. That some of them are real objects of charity, cannot be doubted. But why you, my brethren, should be required, or expected, to maintain the idle and the intemperate out of your sober earnings, is more than I can comprehend. It is true, that many of these wretches, (I cannot employ a milder term,) have families, which must not be left to starve. Of their children, I shall speak more particularly under the next head. But how shall we get over the present necessity? Shall we give, or shall we not give, to these next door neighbours to the poor-house? What are the duties which we owe them? An outline of my views, on this part of our subject, is contained in the following brief observations. It is a fundamental principle with me, that nothing should be done, which has a known tendency to encourage indolence or improvidence. It is of the first importance, that you should acquaint yourselves fully with the habits, character and circumstances of those whom you are called upon to relieve. In this way, you will find, that some evidently prefer charity to the rewards of industry. A strong, healthy person, well known in the town where I once resided, used unblushingly to give this reason for spending her time in begging, that she could get more by it, than by her labour. Many, I doubt not, secretly act upon the same principle; and from such persons every thing ought to be withheld, till stern necessity drives them to some honest calling for a living. The rule of the Apostle, already quoted, is plain and peremptory. “If any man will not work, neither should he eat.” Now if the idle have no right to eat, I have no right to feed them; for in so doing, I shall become, in some degree at least, accessory to their guilt.

Your aid, my brethren, to the necessitous around you, should, as far as possible, be afforded in the shape of encouragement to industry. This is the true way of doing good to the poor, who have any ability left of helping themselves. He that encourages and assists them to earn five dollars, is a greater benefactor, than if he had given them fifty out of his own pocket. By turning your attention to the subject, you will easily find various expedients for the encouragement of industry among that class of the poor of whom I am now speaking.

Sometimes employ them, even when you could do without their labour. Pay them generously and promptly for every thing they do, and frequently add some small gratuity. If they cannot go abroad, furnish them with the materials of industry at their own houses. If you find them faithful and honest, make interest for them with your friends. Strive to gain their confidence. Enter into their feelings. Assist them in laying out their money to the best advantage. Teach them how to make the most of a little. Inculcate the importance of cleanliness, economy and sobriety. Fail not to check the first symptoms of pride, or unnecessary expence in their own or their children’s dress. Hold up this before them continually, that if they expect help from you, they must help themselves; that they must not look to you for succor in sickness, unless they are diligent and saving in time of health. When the feeble try to walk, and cannot support themselves, reach them a helping hand. When their contrivance fails, contrive for them. Labour to inspire them with confidence in their own resources and efforts. Teach them to rely, under Providence, as much as possible upon themselves. Employ that ascendency, which their dependence upon your bounty and friendship can hardly fail to give you, for promoting their moral and religious improvement. Earnestly inculcate the duties of temperance, frugality, honesty, thankfulness to God for all his benefits, contentment under the allotments of Providence, and universal holiness of heart and life.

Let this course be judiciously and perseveringly pursued, and great good might certainly be done, with small means. By the blessing of God, not a few of the vicious might be reclaimed. To the hopes and exertions of the desponding, a new spring might be given, which would soon release them from dependence on their neighbours; and thus, instead of multiplying, this class of the poor would be diminished from year to year.

There may be some, indeed, on whom no salutary impressions can be made; men, with whom the abuse of your beneficence is a matter of calculation; men, who either earn nothing, or squander what they earn, under the impression, that when their families come to want, they will be supported by the hand of charity, and that they themselves shall enjoy a large share of their neighbour’s bounty. In the meantime, others of the same character, standing by and witnessing the success of this diabolical experiment, are induced to embark in the same speculation upon your sympathies, and in this way, the indiscreet bestowment of charity upon one undeserving object, may prove the indirect cause of impoverishing many families.

In cases like these, where human shapes are utterly lost to honour, and shame, and gratitude, and conscience, I can think of no remedy, but the strong arm of the law. Let not that corrective, then, sleep an hour in your statute-book. Let those worse than infidel husbands and fathers, who will not provide for their own households, be visited with the heaviest legal penalties, which the wisdom of your ancestors has provided, as a just retribution upon their heads, and a solemn warning to others.

From the preceding sketch of what is due to the adult poor, we pass,

2. To consider what can be done for their children.—Here, I think, the general course which ought to be pursued is plain. The children of the poor should be regarded equally with others, as rational, accountable and immortal beings; as equally with others, as rational, accountable and immortal beings; as equally capable of improvement in knowledge, in virtue, in holiness; as no unlikely candidates, under wise management, for wealth, and power, and influence. If your first object, therefore, should be to clothe their nakedness and satisfy the cravings of hunger, your ultimate views should be directed to more important and durable benefits. Upon your wisdom, union and perseverance, in regard to their education, using the term in its largest sense, almost every thing must depend. By proper management, they may become useful members of society, and even ornaments of the next generation. But should their education be neglected, what can you expect from them hereafter, but ignorance, vice and poverty? Let them all, then, be sent early to school. Let them be faithfully instructed in common learning, at the public expence. Let them, as early as possible, be placed in good families, where they may be well fed and clothed; where they may be trained up in habits of industry and sobriety, and where their minds may be early imbued with the principles of sound morality and true religion. Your laws have very wisely devolved this duty upon the selectmen, as overseers of the poor, and have constituted them the guardians and protectors of such children. But these overseers ought to be assisted in finding suitable places, by all who wish well to the poor, and who have a desire to promote the best interests of society. In order to give full effect to this benevolent provision, the pious and charitable must sometimes make a trifling sacrifice of present interest, by receiving poor children into their families, before they are old enough to earn their living.

I have no time, brethren, to fill up the outline of this plan. You will easily do it at your leisure. It has no claim to originality. Time was, when it was extensively pursued in New-England, and was productive of the best effects. O may that bright sun of better days speedily shine again upon the sons of the pilgrims!

It now only remains,

3. Under this head, that we direct our inquiries to those great moral and religious preventives of poverty, which alone can stay the plague. Without derogating, in the smallest degree, from the importance of foregoing topics, this must confessedly stand pre-eminent. It is always better, and generally much easier, to prevent evils, than to cure them. He who visits the sick, and administers consolation to the dying, when the yellow-fever is spreading desolation over a great city, does well; but he who effectually guards against the introduction of this terrible disease, or prevents it, by a timely removal of the causes of contagion, does better. If we have not been unprofitably employed, in contriving how to check the growth, and lop off the branches of a baleful stock, it is not, after all, like “laying the axe unto the root of the tree. It is not enough to show how needless pauperism may be kept within its present limits, or even very much contracted; we must, if possible, dry up the sources of this turbid and turbulent stream. Happily, all the requisite means are placed, by a kind Providence, within our reach. If we ultimately fail, it will be our own fault, and the fault of those who ought to co-operate with us, in this benevolent enterprise. The causes of poverty have been enumerated, and to these we must direct our earnest attention. We must raise a warning voice against prodigality, which, like a pitiless whirlpool, has ingulfed thousands of our countrymen, ere they saw or suspected the danger. We must do every thing in our power, both by precept and example, to discountenance pride and extravagance of every kind, as prominent causes of numberless attachments and sales at auction, followed by a long and melancholy train of houseless, supperless, broken-hearted families. It is especially incumbent on the wealthy, not to be extravagant in their dress, or their entertainments; as every thing of this sort has an extremely mischievous influence upon society. What though you may be able, without seriously feeling the expence, to entertain large parties, and feast them upon all the delicacies that can be purchased with money; your guests, your intimate friends, perhaps, can ill afford to return the civility. And must it not be unkind in you, (I have selected the mildest term) to raise the style of this kind of social intercourse so much above their reach, that they must either impoverish their families, to emulate your profusion, or receive you with a mortifying consciousness of the striking contrast between their tables and yours? What a mighty influence would plainness and frugality, in the higher walks of life, have, to check the growth of extravagance among all classes of men, and in this way, by removing the cause, to prevent much of the shame and many of the sufferings of poverty.

Again: As idleness is known to clothe such multitudes with rags, we must use every proper argument, and employ all suitable measures, to promote industry. As intemperance is seen to be the great cause of causes, by which humanity is disgraced and our poor-houses are crowded, we must direct our most strenuous efforts against this crying sin, this sweeping curse, this raging pestilence, this devouring conflagration, this horrible reproach of our land! We must consider whence we are fallen; must revert to first principles; must begin at the foundation. If all men were honest, sober, industrious, frugal and virtuous; if none were addicted to expensive and ruinous vices, it is certain there would be no unnecessary poverty. Whatever, then, has a tendency to prevent vice and immorality; to form good habits and good principles, must be a preventive of pauperism.

Education, (especially that part of it which is denominated moral and religious;) education is the great instrument by which, with a divine blessing, the next generation may be freed from most of the burdens and miseries which we now feel and witness. Yes, my brethren, God has put into our hands a more potent lever than Archimedes ever dreamed of; and the bible has discovered to us that other world, which he could never find, where we may place our machinery for moving this!

We must, then, unite our exertions, our prayers, and our influence, in the grand business of education. The infant mind is wonderfully susceptible. Moral impressions, either good or bad, will it receive, much earlier than is generally supposed; and it is our business, while we guard against wrong impressions, to sow the seeds of virtue and religion.

Childhood is the prime of spring. It is a short and critical period. It is the true golden age, which never returns. Government and subordination, moral and religious instruction, must commence in families. Parents must teach their children diligently, and must enforce their precepts by a corresponding example. Schools must be cheerfully and liberally patronized. Great care must be exercised in the choice of instructers; and they must be encouraged and supported in all their measures. Every teacher must be required to inculcate good principles upon the minds of his pupils, to make his school, if possible, a nursery of piety, as well as literature. The bible and the catechism must be restored to their place and use, both in the school-room and family. Children must be taught, from their infancy, to abhor falsehood, profaneness, drinking, gaming and every other evil habit. They must be faithfully trained up in habits of industry and economy. Idleness, at any age, is vice, and vice is ruin. Children must be taught to despise every mean and sordid action. They must be warned against associating with wicked companions; must be kept as far as possible from all the haunts of vice, and must be accustomed to seek enjoyment in that kind of society, where their minds may be improved, and every virtuous habit strengthened. Above all, they must be brought up in the fear of God. They must be taught to look up to him as their Creator, Preserver and Judge; to humble themselves before him as sinners; to believe on the name of his Son Jesus Christ; to take his word for their rule; to love their neighbours as themselves, and to lay up their treasures in heaven.

Let this course be pursued, my brethren, with the rising generation; let the preceding outline be filled up by parents, guardians, school-masters and ministers, and you will hereafter have very few candidates for the poor-house. Take this plain course, and by God’s blessing, your children will be sober, industrious and comfortable, in their worldly circumstances. Your sons will walk with the wise men and will be wise, and not with fools, whose “end is destruction, whose God is their belly, who glory in their shame.”

They will shun and abhor the dram-shop, as they would the mouth of the lion, or the embraces of a serpent. They will be the “crown of your gray hairs,” instead of “bringing them down with sorrow to the grave.” They will be “eyes, and feet, and hands to you, when those that look out of the windows are darkened, and the strong men bow themselves.” In the time of sickness, they will watch over you with filial affection; will support your heads and close your eyes in the hour of death; will bedew your clay with no ambiguous tears, and will bless your memory.

Think not, my brethren, that this is the baseless fabric of a vision. It is but a plain, unvarnished sketch of the blessed effects of a virtuous and pious education. “Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old, he will not depart from it.”

But chiefly owing to former neglects, one thing further is necessary, to remove the existing causes of pauperism, and save our children from the contamination to which they are now exposed. The laws against vice and immorality must be executed upon such, if any such there are, as will not be reformed by milder means. There are evil habits which must be corrected; bad examples which must not be tolerated; inroads upon our moral and religious institutions which must no longer be winked at. The laws against tippling, swearing, gaming and Sabbath breaking, must be executed, with a prudent, but steady and determined hand. Against intemperance especially, every friend of God and man must boldly lift up his voice, and exert all his influence.

The cries of starving and shivering families against dram-shops, and other similar resorts, in every part of our land, have long since gone up to heaven; and they must no longer die away unheeded, upon human ears. These gates of hell must be closed, locked, bolted, barred and covered with death’s heads, flames and furies!

I say, my brethren, there must be one grand and united effort, for the support of all that is dear in society, and to prevent the increase of those intolerable burdens, which idleness and profligacy have everywhere, almost, imposed upon virtue and industry. Let the excellent laws of this Commonwealth be awaked, if they have been left to fall asleep: Let them rise in their majesty and their might, and your poor rates will soon be diminished more than one half; and in the place of rags, and dirt, and hunger, and cold, you will find cleanliness, sobriety and competence. Yes, my brethren, every moral, religious and legal preventive of poverty, which has been named, or omitted, must be employed, with a humble reliance on the blessing of God, and the work will soon be done.

It is no new system, which I have proposed for the prevention of pauperism. I plead for no dubious experiments. I only request that you will “stand in the way, and ask for the old paths.” It is not left for us to digest a system of education, adapted to the genius of a free government, and calculated to diffuse the blessings of science, virtue and religion through the whole community. Such a system was matured and in successful operation, long before we were born.

Our ancestors have not devolved upon us the difficult task of framing, in a degenerate age, all the necessary laws for the punishment of evil doers, the prevention of crimes, the encouragement of sobriety and industry; and whatever else is essential to the well-being of society. Almost every thing is prepared to our hands, and has come down to us from our ancestors, the pious fathers of New-England. I need not say, how much those illustrious founders of our happy republic have been ridiculed and vilified, as weak, and bigoted, and fanatical, by some of their puny and degenerate offspring. But I will say, without fear of contradiction, that they were higher from their shoulders and upward, than their tallest revilers: that there were men among them, who, for rectitude of principle, soundness of judgment, largeness of views, and piety of heart, would not suffer in comparison with the wisest and best legislators of any age or country. The whole world may be challenged to produce a code of laws, which, for the government of a free and enlightened people, can be compared, for one moment, with those which they bequeathed to posterity.

It is wonderful to observe, in their early statutes and institutions, with what prospective, I had almost said prophetic sagacity, they guarded against almost every danger, civil, political, moral and religious, which might menace the security and prosperity of their descendants. Had the laws which they framed been faithfully executed; had their noble spirit proved hereditary; had their “mantle” fallen upon their children, and then upon their children’s children, vice would never have gained its present alarming ascendency. The evils and sufferings of poverty would have been comparatively few and light. It is by degeneracy that we have brought upon ourselves these heavy burdens, and that we stand exposed to still greater evils. We have stood by, with our arms folded, and permitted the enemy to make wide breaches in our walls; to drive our sentinels before them, and to overawe the whole garrison. Let us now, at length, arise, expel these “armies of the aliens;” build up these breaches; adhere steadily to the principles and measures of our forefathers, and we shall reap a rich harvest of public and private blessings.

We have only to repair the machinery which our ancestors have bequeathed us; to brush away the cobwebs and rub off the rust, which have accumulated through disuse; to put and keep the wheels and springs in motion, and the reformation, which every good man prays for, will follow almost of course. It now only remains,

IV. To suggest motives and encouragements for a speedy, united and persevering course of measures, for accomplishing so important and benevolent a design. But what shall I say? I have scarcely room left for a bare enumeration of these interesting topics. They present themselves in every view which can be taken of the subject, and press upon the considerate mind, with an urgency, which admits of no delay. They appeal to your interest, to your philanthropy, to your “bowels and mercies,” to your consciences, to your affections, and indeed, to every feeling, to every principle, which ought to govern a rational and benevolent mind.

If the means which have been pointed out for bettering the condition of the poor; for stimulating them to exertion, by the honours and substantial rewards of industry; for affording prompt and adequate relief to the helpless; for clearing our streets of profligate beggars; for compelling the idle and intemperate to maintain themselves; for educating poor children and placing them in good families: if these means are all brought, by a kind Providence, within your reach, then you cannot neglect them,, without incurring the guilt of outraging both humanity and benevolence. If you have it in your power to dry up so many sorrows, to remove so many causes of pauperism, by your exertions and example; if the moral and religious preventives of this wasting and spreading disease are placed, by a merciful God, in your hands, will you not hold yourselves solemnly bound to unite in every proper measure for warding off evils so many and so terrible, and for the attainment of blessings so desirable to the present generation, and so important in their future consequences.

Think of the difference between a sober, industrious, moral, religious, well-educated and prosperous people, and an ignorant, unprincipled, unpolished, drinking, quarrelsome, stupid, idle and beggarly population. Consider what it is that makes this immense difference, and surely you cannot fail of being impressed with the overwhelming importance of our subject. Do you, then, my brethren, pity the poor? Have you any compassion for those who are past feeling for themselves; who are eagerly sacrificing their food and raiment, their reputation, their health, their consciences, their bodies and their souls on the altars of Bacchus? Have you any feeling for their broken-hearted wives and suffering children? Are your hearts affected with what your eyes see and your ears hear? Does the love of Christ constrain you? Has the bible any influence upon your minds? Then you will not be “forgetful hearers, but doers of the word.” You will unite heart and hand, in persevering exertions to better the condition of those who are now dependent upon the aids of charity, and to bring into full operation those moral and religious preventives, which have been pointed out in this discourse. “Blessed is he that considereth the poor: the Lord will deliver him in time of trouble. The Lord will preserve him and keep him alive, and he shall be blessed upon the earth: and thou wilt not deliver him unto the will of his enemies. The Lord will strengthen him upon the bed of languishing; thou wilt make all his bed in his sickness.”

What shall I say more? Look a moment, brethren, at the heavy bearing of this subject upon taxation. This is one of the smallest evils attendant upon the alarming prevalence and rapid increase of needless pauperism. But even this, I think you will say, is no trifle. See how it affects your property. Fifteen hundred, or two thousand dollars annually, is no small sum for a town, containing 2600 inhabitants, to pay for the support of its poor. Possibly one third of this sum is necessary, to maintain such as have been reduced to want by sickness, derangement, unavoidable losses, and other adverse circumstances. What becomes of the other two thirds; of one thousand dollars, at least, paid every year out of your hard earnings? I need not stop to answer so plain a question. Go to the poor-house, and ask from the beginning to the end of the alphabet, How came you here? Go to the grog-shop, and if you can hold your breath long enough, count up the mysterious marks upon the walls and the shelves.

And will you continue to pay this enormous tax? If you suffer things to go on in their present course, you must pay it, with ten or fifteen per cent. In addition, every twelve months. You may remonstrate and put off, but there is no relief. The day of settlement will come, and the collector must be satisfied.

Have you seriously thought of the subject in this light? Do you consider, that almost every idler and drunkard in the community, is a public pensioner? Are you sensible, when you see men reducing their families to want, by tippling and its attendant vices, that you have got to be four-folded, for all this waste of health, and time, and property? Do you know, that while a man is drinking up his own estate, he is every day lessening the value of yours? That while you stand by and calmly look on, he is actually laying a mortgage upon every foot of your lands, which neither you nor your children can ever pay off? This whether you realize it or not, is capable of mathematical demonstration. Dram-shops are kept up at your expence. The revenue of those who subsist by dealing out ardent spirits to hard drinkers, is indirectly drawn from your pockets. You will find it charged to you, with heavy interest, in the rote-book. The intemperate are constantly running you in debt without your consent. They are doing it from day to day, when you are at work, and from night to night, while you are asleep. And are you willing to be taxed in this way, for that which does you no good; and to have these accumulating burdens entailed upon your posterity? I know you are not, and I have pointed out the means of relief.

“Choose ye this day” what you will do; whether you will endeavour to “make the tree good, that its fruit may be good;” whether you will go to work in earnest, to lessen the evils and expences of existing poverty; whether you will faithfully test the efficacy of those preventives on which I have insisted, or whether, “despairing of the Commonwealth,” you will flee before increasing swarms of foreign beggars and resident paupers; and thus exchange the blessings of industry, competence, education, social enjoyment and religious order, for hunger and nakedness, ignorance and profligacy, idleness and ruin.

I do not say, that you can banish poverty from your borders, or that you ought to attempt it. “Ye have the poor with you always;” and this is wisely ordered, no doubt, that you may have opportunity to show your gratitude to God, and your compassion for suffering humanity, by giving to him that needeth. Sickness, and other adversities, will bring their well substantiated claims to your doors; but these, presented in behalf of the virtuous and deserving poor, will be few, in comparison with those which are now arrogantly preferred, by lying vagrancy and resident improvidence.