Today, most Americans are taught Black History from a southern point of view. That is, they are exposed to the slave trade and the atrocities of slavery that were common in the South but hear nearly nothing about the many positive things that occurred in the North.

Today, most Americans are taught Black History from a southern point of view. That is, they are exposed to the slave trade and the atrocities of slavery that were common in the South but hear nearly nothing about the many positive things that occurred in the North.

For example, who has been taught about Wentworth Cheswell1 — the first black elected to office in America, in 1768 in New Hampshire? Or the election of Black American Thomas Hercules to office in Pennsylvania in 1793? Or that in Massachusetts, blacks routinely voted in colonial elections? Or that when the Constitution was ratified in Maryland, more Blacks than Whites voted in Baltimore? Such stories are absent from textbooks today.

History is properly to teach the good, the bad, and the ugly — all of it; but students today usually get only the bad and the ugly, rarely the good. For example, students are regularly told that the first load of slaves sailed up the James River in Virginia in 1619 and thus slavery was introduced into America,2 but few learn about the first slaves that arrived in the Massachusetts Colony set up by the Christian Pilgrims and Puritans. When that slave ship arrived in Massachusetts, the ship’s officers were arrested and imprisoned, and the kidnapped slaves were returned to Africa at the Colony’s expense.3 That positive side of history is untold today.

Similarly, most Americans are unaware that American colonies passed anti-slavery laws before the American Revolution, but that those laws were vetoed by Great Britain, who insisted on the continuance of slavery in America. In fact, several Founders who owned slaves while British citizens freed them once America declared her independence. Sadly, we have been taught to identify Founding Fathers who owned slaves but are unaware of the greater number who opposed slavery or worked with anti-slavery societies.

Similarly, most Americans are unaware that American colonies passed anti-slavery laws before the American Revolution, but that those laws were vetoed by Great Britain, who insisted on the continuance of slavery in America. In fact, several Founders who owned slaves while British citizens freed them once America declared her independence. Sadly, we have been taught to identify Founding Fathers who owned slaves but are unaware of the greater number who opposed slavery or worked with anti-slavery societies.

WallBuilders owns numerous documents showing these positive aspects of Black History, including of praiseworthy efforts to end oppression of African Americans.

For example, the 1774 letter on the right is from Quaker John Townsend, who wrote to inquire after an African slave he had earlier sold. He wanted to reacquire that slave in order to “have the opportunity to set her free.” (The Quakers, like several colonial denominations, firmly opposed slavery and pushed their members to do all possible to end the evil.)

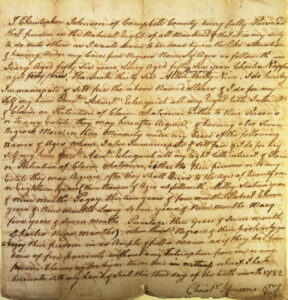

In this 1782 document, Christopher Johnson, a soldier in the American Revolution, declares that he is “fully persuaded that freedom is the natural rights of all mankind & that it is my duty to do unto others as I would desire to be done by in the like situation.” Having fought a war to win his own political freedom, and invoking the Golden Rule delivered by Jesus in Matthew 7:12, he freed (that is, manumitted) his slaves.

In this 1782 document, Christopher Johnson, a soldier in the American Revolution, declares that he is “fully persuaded that freedom is the natural rights of all mankind & that it is my duty to do unto others as I would desire to be done by in the like situation.” Having fought a war to win his own political freedom, and invoking the Golden Rule delivered by Jesus in Matthew 7:12, he freed (that is, manumitted) his slaves.

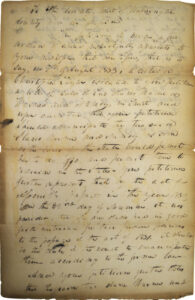

In this 1837 document, Dorcas, a Black American who is “a free woman of color,” petitions the court to recognize the legality of two slaves that were freed. According to the Tennessee Act of 1831,4 freed slaves were required to move out of the state, but the subsequent act of 18335 permitted slaves to remain in the state if they had received their freedom prior to 1831. In her letter, Dorcas affirms that “the said two slaves, Warner and Nancy” had received “their freedom long before the passage of the act of 1831” and asks the court to take appropriate action for ensuring their freedom.

In this 1837 document, Dorcas, a Black American who is “a free woman of color,” petitions the court to recognize the legality of two slaves that were freed. According to the Tennessee Act of 1831,4 freed slaves were required to move out of the state, but the subsequent act of 18335 permitted slaves to remain in the state if they had received their freedom prior to 1831. In her letter, Dorcas affirms that “the said two slaves, Warner and Nancy” had received “their freedom long before the passage of the act of 1831” and asks the court to take appropriate action for ensuring their freedom.

On our website, there are many more such documents and many inspiring stories, illustrating a side of Black History of which few Americans are told today

Endnotes

1 “A Black Patriot: Wentworth Cheswell,” WallBuilders, https://wallbuilders.com/resource/a-black-patriot-wentworth-cheswell/.

2 “Slavery,” Harper’s Encyclopaedia of United States History, ed. Benson Lossing (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1974); W. O. Blake, The History of Slavery and the Slave Trade (Columbus: J. & H. Miller, 1858), 98.

3 Blake, History of Slavery (1858), 370-371; Thomas R.R. Cobb, An Inquiry into the Law of Negro Slavery (Philadelphia: T. & J. W. Johnson & Co., 1858), I:cxlvii-cxlviii; W. E. Burghardt DuBois, The Suppression of the AfricanSlave-Trade to the United States of America (New York: Social Science Press, 1954), 30.

4 “Emancipation: 1831–Chapter 102,” A Compilation of the Statutes of Tennessee, Of a General and Permanent Nature, From the Commencment of the Government to the Present Time, eds. R. L. Caruthers & A. O. P. Nicholson (Nashville: James Smith, 1836), 279.

5 “An Act to explain an act, entitled “an act concerning free persons of color, and for other purpose,” passed December 16, 1831,” November 23, 1833, Public Acts Passed at the First Session of the Twentieth General Assembly of the State of Tennessee 1833 (Nashville: Allen A. Hall & F. S. Heiskell, 1833), 99-100.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!