During the early days of the War for Independence—while the gun smoke still covered the fields at Lexington and Concord, and the cannons still echoed at Bunker Hill—America faced innumerable difficulties and a host of hard decisions. Unsurprisingly, the choice of a national flag remained unanswered for many months due to more pressing issues such as arranging a defense and forming the government.

During the early days of the War for Independence—while the gun smoke still covered the fields at Lexington and Concord, and the cannons still echoed at Bunker Hill—America faced innumerable difficulties and a host of hard decisions. Unsurprisingly, the choice of a national flag remained unanswered for many months due to more pressing issues such as arranging a defense and forming the government.

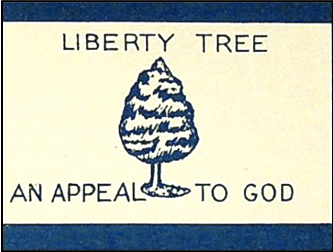

However, a flag was still needed by the military in order to differentiate the newly forged American forces from those of the oncoming British. Several temporary flags were swiftly employed in order to satisfy the want. One of the most famous and widespread standards rushed up flagpoles on both land and sea was the “Pinetree Flag,” or sometimes called “An Appeal to Heaven” flag.

As the name suggests, this flag was characterized by having both a tree (most commonly thought to be a pine or a cypress) and the motto reading “an appeal to Heaven.” Typically, these were displayed on a white field, and often were used by troops, especially in New England, as the liberty tree was a prominent northern symbol for the independence movement.1

In fact, prior to the Declaration of Independence but after the opening of hostilities, the Pinetree Flag was one of the most popular flags for American troops. Indeed, “there are recorded in the history of those days many instances of the use of the pine-tree flag between October, 1775, and July, 1776.”2

In fact, prior to the Declaration of Independence but after the opening of hostilities, the Pinetree Flag was one of the most popular flags for American troops. Indeed, “there are recorded in the history of those days many instances of the use of the pine-tree flag between October, 1775, and July, 1776.”2

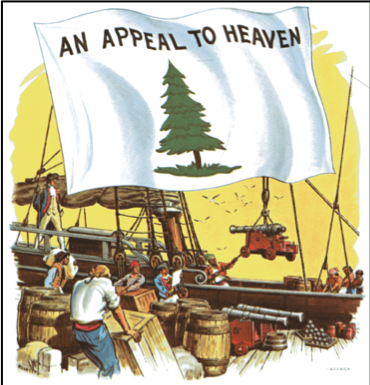

Some of America’s earliest battles and victories were fought under a banner declaring “an appeal to Heaven.” Some historians document that General Israel Putnam’s troops at Bunker Hill used a flag with the motto on it, and during the Battle of Boston the floating batteries (floating barges armed with artillery) proudly flew the famous white Pinetree Flag.3 In January of 1776, Commodore Samuel Tucker flew the flag while successfully capturing a British troop transport which was attempting to relieve the besieged British forces in Boston.4

The Pinetree Flag was commonly used by the Colonial Navy during this period of the War. When George Washington commissioned the first-ever officially sanctioned military ships for America in 1775, Colonel Joseph Reed wrote the captains asking them to:

Please to fix upon some particular color for a flag, and a signal by which our vessels may know one another. What do you think of a flag with a white ground, a tree in the middle, the motto ‘Appeal to Heaven’? This is the flag of our floating batteries.5

In the following months news spread even to England that the Americans were employing this flag on their naval vessels. A report of a captured ship revealed that, “the flag taken from a provincial [American] privateer is now deposited in the admiralty; the field is a white bunting, with a spreading green tree; the motto, ‘Appeal to Heaven.’”6

As the skirmishes unfolded into all out warfare between the colonists and England, the Pinetree Flag with its prayer to God became synonymous with the American struggle for liberty. An early map of Boston reflected this by showing a side image of a British redcoat trying to rip this flag out of the hands of a colonist (see image on right).7 The main motto, “An Appeal to Heaven,” inspired other similar flags with mottos such as “An Appeal to God,” which also often appeared on early American flags.

As the skirmishes unfolded into all out warfare between the colonists and England, the Pinetree Flag with its prayer to God became synonymous with the American struggle for liberty. An early map of Boston reflected this by showing a side image of a British redcoat trying to rip this flag out of the hands of a colonist (see image on right).7 The main motto, “An Appeal to Heaven,” inspired other similar flags with mottos such as “An Appeal to God,” which also often appeared on early American flags.

For many modern Americans it might be surprising to learn that one of the first national mottos and flags was “an appeal to Heaven.” Where did this phrase originate, and why did the Americans identify themselves with it?

To understand the meaning behind the Pinetree Flag we must go back to John Locke’s influential Second Treatise of Government (1690). In this book, the famed philosopher explains that when a government becomes so oppressive and tyrannical that there no longer remains any legal remedy for citizens, they can appeal to Heaven and then resist that tyrannical government through a revolution. Locke turned to the Bible to explain his argument:

To avoid this state of war (wherein there is no appeal but to Heaven, and wherein every the least difference is apt to end, where there is no authority to decide between the contenders) is one great reason of men’s putting themselves into society and quitting [leaving] the state of nature, for where there is an authority—a power on earth—from which relief can be had by appeal, there the continuance of the state of war is excluded and the controversy is decided by that power. Had there been any such court—any superior jurisdiction on earth—to determine the right between Jephthah and the Ammonites, they had never come to a state of war, but we see he was forced to appeal to Heaven. The Lord the Judge (says he) he judge this day between the children of Israel and the children of Ammon, Judg. xi. 27.8

Locke affirms that when societies are formed and systems and methods of mediation can be instituted, armed conflict to settle disputes is a last resort. When there no longer remains any higher earthly authority to which two contending parties (such as sovereign nations) can appeal, the only option remaining is to declare war in assertion of certain rights. This is what Locke calls an appeal to Heaven because, as in the case of Jephthah and the Ammonites, it is God in Heaven Who ultimately decides who the victors will be.

Locke goes on to explain that when the people of a country “have no appeal on earth, then they have a liberty to appeal to Heaven whenever they judge the cause of sufficient moment [importance].”9 However, Locke cautions that appeals to Heaven through open war must be seriously and somberly considered beforehand since God is perfectly just and will punish those who take up arms in an unjust cause. The English statesman writes that:

he that appeals to Heaven must be sure he has right on his side; and a right to that is worth the trouble and cost of the appeal as he will answer at a tribunal that cannot be deceived [God’s throne] and will be sure to retribute to everyone according to the mischiefs he hath created to his fellow subjects; that is, any part of mankind.10

The fact that Locke writes extensively concerning the right to a just revolution as an appeal to Heaven becomes massively important to the American colonists as England begins to strip away their rights. The influence of his Second Treatise of Government (which contains his explanation of an appeal to Heaven) on early America is well documented. During the 1760s and 1770s, the Founding Fathers quoted Locke more than any other political author, amounting to a total of 11% and 7% respectively of all total citations during those formative decades.11 Indeed, signer of the Declaration of Independence Richard Henry Lee once quipped that the Declaration had been largely “copied from Locke’s Treatise on Government.”12

The fact that Locke writes extensively concerning the right to a just revolution as an appeal to Heaven becomes massively important to the American colonists as England begins to strip away their rights. The influence of his Second Treatise of Government (which contains his explanation of an appeal to Heaven) on early America is well documented. During the 1760s and 1770s, the Founding Fathers quoted Locke more than any other political author, amounting to a total of 11% and 7% respectively of all total citations during those formative decades.11 Indeed, signer of the Declaration of Independence Richard Henry Lee once quipped that the Declaration had been largely “copied from Locke’s Treatise on Government.”12

Therefore, when the time came to separate from Great Britain and the regime of King George III, the leaders and citizens of America well understood what they were called upon to do. By entering into war with their mother country, which was one of the leading global powers at the time, the colonists understood that only by appealing to Heaven could they hope to succeed.

For example, Patrick Henry closes his infamous “give me liberty” speech by declaring that:

If we wish to be free—if we mean to preserve inviolate those inestimable privileges for which we have been so long contending—if we mean not basely to abandon the noble struggle in which we have been so long engaged, and which we have pledged ourselves never to abandon—we must fight!—I repeat it, sir, we must fight!! An appeal to arms and to the God of Hosts, is all that is left us!13

Furthermore, Jonathan Trumbull, who as governor of Connecticut was the only royal governor to retain his position after the Declaration, explained that the Revolution began only after repeated entreaties to the King and Parliament were rebuffed and ignored. In writing to a foreign leader, Trumbull clarified that:

On the 19th day of April, 1775, the scene of blood was opened by the British troops, by the unprovoked slaughter of the Provincial troops at Lexington and Concord. The adjacent Colonies took up arms in their own defense; and the Congress again met, again petitioned the Throne [the English king] for peace and settlement; and again their petitions were contemptuously disregarded. When every glimpse of hope failed not only of justice but of safety, we were compelled, by the last necessity, to appeal to Heaven and rest the defense of our liberties and privileges upon the favor and protection of Divine Providence; and the resistance we could make by opposing force to force.14

John Locke’s explanation of the right to just revolution permeated American political discourse and influenced the direction the young country took when finally being forced to appeal to Heaven in order to reclaim their unalienable rights. The church pulpits likewise thundered with further Biblical exegesis on the importance of appealing to God for an ultimate redress of grievances, and pastors for decades after the War continued to teach on the subject. For example, an 1808 sermon explained:

War has been called an appeal to Heaven. And when we can, with full confidence, make the appeal, like David, and ask to be prospered according to our righteousness, and the cleanness of our hands, what strength and animation it gives us! When the illustrious Washington, at an early stage of our revolutionary contest, committed the cause in that solemn manner. “May that God whom you have invoked, judge between us and you,” how our hearts glowed that we had such a cause to commit!15

Thus, when the early militiamen and naval officers flew the Pinetree Flag emblazoned with its motto “An Appeal for Heaven,” it was not some random act with little significance or meaning. Instead, they sought to march into battle with a recognition of God’s Providence and their reliance on the King of Kings to right the wrongs which they had suffered. The Pinetree Flag represents a vital part of America’s history and an important step on the journey to reaching a national flag during the early days of the War for Independence.

Furthermore, the Pinetree Flag was far from being the only national symbol recognizing America’s reliance on the protection and Providence of God. During the War for Independence other mottos and rallying cries included similar sentiments. For example, the flag pictured on the right bore the phrase “Resistance to Tyrants is Obedience to God,” which came from an earlier 1750 sermon by the influential Rev. Jonathan Mayhew.16 In 1776 Benjamin Franklin even suggested that this phrase be part of the nation’s Great Seal.17 The Americans’ thinking and philosophy was so grounded on a Biblical perspective that even a British parliamentary report in 1774 acknowledged that, “If you ask an American, ‘Who is his master?’ He will tell you he has none—nor any governor but Jesus Christ.”18

Furthermore, the Pinetree Flag was far from being the only national symbol recognizing America’s reliance on the protection and Providence of God. During the War for Independence other mottos and rallying cries included similar sentiments. For example, the flag pictured on the right bore the phrase “Resistance to Tyrants is Obedience to God,” which came from an earlier 1750 sermon by the influential Rev. Jonathan Mayhew.16 In 1776 Benjamin Franklin even suggested that this phrase be part of the nation’s Great Seal.17 The Americans’ thinking and philosophy was so grounded on a Biblical perspective that even a British parliamentary report in 1774 acknowledged that, “If you ask an American, ‘Who is his master?’ He will tell you he has none—nor any governor but Jesus Christ.”18

This God-centered focus continued throughout our history after the Revolutionary War. For example, in the War of 1812 against Britain, during the Defense of Fort McHenry, Francis Scott Key penned what would become our National Anthem, encapsulating this perspective by writing that:

Blest with vict’ry and peace may the heav’n rescued land

Praise the power that hath made and preserv’d us a nation!

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto: “In God is our trust.”19

In the Civil War, Union Forces sang this song when marching into battle. In fact, Abraham Lincoln was inspired to put “In God we Trust” on coins, which was one of his last official acts before his untimely death.20 And after World War II, President Eisenhower led Congress in making “In God We Trust” the official National Motto,21 also adding “under God” to the pledge in 1954.22

Throughout the centuries America has continually and repeatedly acknowledged the need to look to God and appeal to Heaven. This was certainly evident in the earliest days of the War for Independence with the Pinetree Flag and its powerful inscription: “An Appeal to Heaven.”

Endnotes

1 “Flag, The,” Cyclopaedia of Political Science, Political Economy, and of the Political History of the United States, ed. John Lalor (Chicago: Melbert B. Cary & Company, 1883), 2.232.

2 Report of the Proceedings of the Society of the Army of the Tennessee at the Thirtieth Meeting, Held at Toledo, Ohio, October 26-17, 1898 (Cincinnati: F. W. Freeman, 1899), 80.

3 Schuyler Hamilton, Our National Flag; The Stars and Stripes; Its History in a Century (New York: George R. Lockwood, 1877), 16-17.

4 Report of the Proceedings (1899), 80.

5 Richard Frothingham, History of the Siege of Boston, and of the Battles of Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1849), 261.

6 Frothingham, History of the Siege of Boston (1849), 262.

7 Frothingham, History of the Siege of Boston (1849), 262.

8 John Locke, Two Treatises of Government (London: A. Millar, et al., 1794), 211.

9 Locke, Two Treatises (1794), 346-347.

10 Locke, Two Treatises (1794), 354-355.

11 Donald Lutz, The Origins of American Constitutionalism (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1988), 143.

12 Thomas Jefferson to James Madison, August 30, 1823, National Archives.

13 William Wirt, The Life of Patrick Henry (New York: McElrath & Bangs, 1831), 140.

14 Jonathan Trumbull quoted in James Longacre, The National Portrait Gallery of Distinguished Americans (Philadelphia: James B. Longacre, 1839), 4:5.

15 The Question of War with Great Britain, Examined upon Moral and Christian Principles (Boston: Snelling and Simons, 1808), 13.

16 Jonathan Mayhew, A Discourse Concerning Unlimited Submission and Non-Resistance to the Higher Powers (Boston: D. Fowle, 1750) [Evans # 6549]; John Adams to Abigail Adams, August 14, 1776, National Archives.

17 Benjamin Franklin’s Proposal, August 20, 1776, National Archives.

18 Hezekiah Niles, Principles and Acts of the Revolution in America (Baltimore: William Ogden Niles, 1822), 198.

19 Francis Scott Key, “The Defence of Fort M’Henry,” The Analectic Magazine (Philadelphia: Moses Thomas, 1814) 4:433-434.

20 B. F. Morris, Memorial Record of the Nation’s Tribute to Abraham Lincoln (Washington, DC: W. H. & O. H. Morrison, 1866), 216.

21 36 U.S. Code § 302 – National motto.

22 Dwight Eisenhower, “Statement by the President Upon Signing Bill To Include the Words “Under God” in the Pledge to the Flag,” June 14, 1954, The American Presidency Project.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!