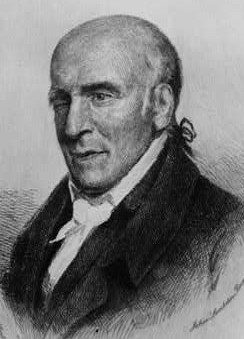

In the last year of his life Daniel Webster (1782-1852) stood before the New York Historical Society and declared:

That if we, and our posterity, shall be true to the Christian religion, if we shall respect his commandments, if we, and they, shall maintain just, moral sentiments, and such conscientious convictions of duty as shall control the heart and life, we may have the highest hopes of the future fortunes of this country.1

Such a stance was, however, not a rarity for Daniel Webster who regularly defended the Christianity throughout his life. One example was in 1844, when Webster rose for the final summation in the case of Vidal v. Girard’s Executors and “delivered one of the most beautiful and powerful arguments in defense of the Christian religion ever uttered.”2

The case concerned the legality of the will of Stephan Girard. In his will Girard had set aside a trust of two million dollars3 for the formation of a college for the education of “as many poor white male orphans, between the ages of six and ten years, as the said income shall be adequate to maintain.”4 The executors of his will, and specifically of the construction and maintenance of the college, were declared the Mayor, Aldermen, and Citizens of Pennsylvania.5 After proceeding through many of the details concerning the organization of the school, Girard lists several “conditions on which my bequest for said college is made and to be enjoyed.”6 The second of these restrictions dictated stipulations regarding the teachers to be employed:

I enjoin and require, that, no ecclesiastic, missionary, or minister of any sect whatsoever, shall ever gold or exercise any station or duty whatever in the said college, nor shall any person ever be admitted for any purpose or as visitor, within the premises appropriated for the purposes of said college.7

After making such a striking demand, Girard attempted to explain and justify this action writing:

In making this restriction, I do not mean to cast any reflection upon any sect or person whatsoever; but as there is such a multitude of sects, and such a diversity of opinion amongst them, I devise to keep the tender minds of the orphans, who are to derive advantage from this bequest, free from the excitements which clashing doctrines and sectarian controversy are so apt to produce.8

The familial heirs of Girard, however, contested the viability the bequest by saying that these sections of the will rendered it void. The plaintiff’s case was argued by Daniel Webster and another preeminent advocate of the day, Walter Jones. The attorneys submitted two main objections to the will. The Court summarized these two objections, writing that:

The principle questions, to which the arguments at the bar have been mainly addressed, are; First, whether the corporation of the city of Philadelphia is capable of taking the bequest of the real and personal estate for the erection and support of a college upon the trusts and for the uses designated in the will: Secondly, whether these uses are charitable uses valid in their nature and capable of being carried into effect consistently with the laws of Pennsylvania.9

The second of these issues addressed whether or not the will was valid according to the laws of Pennsylvania. Webster submitted two reasons why it would be unacceptable. He first argued that the beneficiaries of the bequest (i.e. the “poor white male orphans”) were a category:

So loose a description, that no one can bring himself within the terms of the bequest, so as to say that it was made in his favor. No individual can acquire any right, or interest; nobody, therefore, can come forward as a party, in a court of law, to claim participation in the gift.10

The second objection Webster offers (which takes up the vast majority of his speech) is that the will is invalid due to the breach of the common law by being averse to Christian education. He declares that:

In the view of a court of equity this devise is no charity at all. It is no charity, because the plan of education proposed by Mr. Girard is derogatory to the Christian religion; tends to weakens men’s reverence for that religion, and their conviction of its authority and importance; and therefore, in its general character, tends to mischievous, and not to useful ends.11

Webster argues at length that due to the will banning the presence of any ecclesiastic from ever entering the college compound, Mr. Girard attacks Christianity to such an extent that it will substantially harm the community; thus creating a breach of both the common law of America and the general interests of Philadelphia.12 To show this he questions the Court asking:

Did the man ever live that had a respect for the Christian religion, and yet had no regard for any of its ministers? Did that system of instruction ever exist, which denounced the whole body of Christian teachers, and yet called itself a system of Christianity?13

Pressing further against anti-religious intention he found apparent in Girard’s will, Webster denounces its claim to charity by explaining that any charity which excludes Christ fails to even meet the definition of charity.

No, sir! No, sir! If charity denies its birth and parentage—if it turns infidel to the great doctrines of the Christian religion—if it turns unbeliever—it is no longer charity! There is no longer charity, either in a Christian sense, or in the sense of jurisprudence; for it separates itself from the fountain of its own creation.14

Webster, understanding that the will did not explicitly exclude all Christian teaching, next argues that any attempt to declare the will allows for lay-teaching of religion would be completely antithetical to the spirit and intention of the will—thus rendering the trust equally void. Webster submits that if Girard’s desire was to prevent all conflict concerning the Christian faith from arising and splitting apart the contingent of young scholars, then any religious education would lead to differences of opinion, especially if the students were taught by lay ministers. He inquires:

Now, are not laymen equally sectarian in their views as clergymen? And would it not be just as easy to prevent sectarian doctrines from being preached by a clergyman as being taught by a layman? It is idle, therefore, to speak of lay preaching. … Everyone knows that laymen are as violent controversialists as clergymen, and the less informed the more violent.15

Next Webster takes on the premise of Girard’s exclusion itself. He derides the reasoning of Girard, declaring:

But this objection to the multitude and differences of sects is but the old story—the old infidel argument. It is notorious that there are certain great religious truths which are admitted and believed by all Christians. All believe in the existence of a God. All believe in the immortality of the soul. All believe in the responsibility, in another world, for our conduct in this. All believe in the divine authority of the New Testament. … And cannot all these great truths be taught to children without their minds being perplexed with clashing doctrines and sectarian controversies? Most certainly they can.16

To give an example of how all the various sects and denominations can work, Webster refers the Court to the example the Founding Father’s established in the first Continental Congress. There, setting aside all differences in religious opinions, they came together to pray and ask God’s help in the War for Independence, Webster reminded the Court that many of the delegates doubted the propriety of praying together due to their differences but Samuel admonished them:

It did not become men, professing to be Christian men, who had come together for solemn deliberation in the hour of their extremity, to say that there was so wide a difference in their religious belief, that they could not, as one man, bow the knee in prayer to the Almighty, whose advice and assistance they hoped to obtain.17

Building upon that image of the Founders on their knees in prayer, Webster closes his case by clearly defining the two positions on the issue of Girard’s will. On the one side, there are “those who really value Christianity,” and who “plainly see its foundation, and its main pillars… [who] wish its general principles, and all its truths, to be spread over the whole earth.”18 On the other side, however, are those who do not value Christianity, and thus, “cavil about sects and schisms, and ring monotonous changes upon the shallow and so often refuted objections.”19 With that dichotomy, Webster charged the Court to likewise defend the Christian faith and preserve American society.

Although a unanimous decision for Girard’s executors, the Court, in its written opinion, agreed with all of Webster’s arguments concerning the breach of common law arising from flagrant attacks upon Christianity. Justice Joseph Story, author of the opinion, confirms Webster’s understanding of the law’s relationship to the Christian religion:

It is said, and truly, that the Christian religion is a part of the common law of Pennsylvania.20

We are compelled to admit that although Christianity be a part of the common law of the state, yet it is so in this qualified sense, that its divine origin and truth are admitted, and therefore it is not to be maliciously and openly reviled and blasphemed against, to the annoyance of believers or the injury of the public.21

Such a case is not to be presumed to exist in a Christian country. … There must be plain, positive, and express provisions, demonstrating not only that Christianity is not to be taught; but that it is to be impugned or repudiated.22

In the areas pertaining to Christianity and the common law Webster and the Court concurred. The difference did not come from a disagreement concerning the interpretation of the law, but rather the interpretation of the will. Webster held that where the letter of the will may not have openly assailed Christianity, the spirit of the will clearly did. The Court, however, rejected this interpretation, insisting instead that the exclusion of Christian pastors from the school on the grounds of sectarian conflict did not necessitate exclusion of Christian education in general. Story explains:

But the objection itself assumes the proposition that Christianity is not to be taught, because ecclesiastics are not to be instructors or officers. But this is by no means a necessary or legitimate inference from the premises. Why may not laymen instruct in the general principles of Christianity as well as ecclesiastics. There is no restriction as to the religious opinions of the instructors and officers. … Why may not the Bible, and especially the New Testament, without note or comment, be read and taught as a divine revelation in the college — its general precepts expounded, its evidences explained, and its glorious principles of morality inculcated? What is there to prevent a work, not sectarian, upon the general evidences of Christianity, from being read and taught in the college by lay-teachers? Certainly there is nothing in the will, that proscribes such studies.23

So the Court dismissed Webster’s argument that the will was hostile to Christianity, thus deciding the trust to be valid. Even though the Court differed from Webster’s reading of the will, this case provides an interesting view into the mindset of this early Supreme Court regarding the freedom of religion in American schools. Both Webster and Story advocated clearly for the important role of the Bible in education.

Endnotes

1 Daniel Webster, An Address Delivered before the New York Historical Society (New York: New York Historical Society, 1852), 47.

2 Fanny Lee Jones, “Walter Jones and His Times,” Records of the Columbia Historical Society Vol. V (Washington: Columbia Historical Society, 1902), 144.

3 The Will of the late Stephan Girard (Philadelphia: Thomas Silver, 1848), 16.

4 The Will (1848), 21.

5 The Will (1848), et al.

6 The Will (1848), 22.

7 The Will (1848), 22-23.

8 The Will (1848), 23.

9 Vidal et al. v. Girard’s Executors, 43 US 127, 186 (1844).

10 Daniel Webster, In Defense of the Christian Ministry, and in Favor of the Religious Instruction of the Young (Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1844), 10.

11 Webster, In Defense of the Christian Ministry (1844), 10.

12 Webster, In Defense of the Christian Ministry (1844), 11.

13 Webster, In Defense of the Christian Ministry (1844), 13.

14 Webster, In Defense of the Christian Ministry (1844), 16.

15 Webster, In Defense of the Christian Ministry (1844), 21.

16 Webster, In Defense of the Christian Ministry (1844), 35.

17 Webster, In Defense of the Christian Ministry (1844), 36.

18 Webster, In Defense of the Christian Ministry (1844), 37.

19 Webster, In Defense of the Christian Ministry (1844), 37.

20 Vidal et al. v. Girard’s Executors, 43 US 127, 198 (1844).

21 Vidal et al. v. Girard’s Executors, 43 US 127, 198 (1844).

22 Vidal et al. v. Girard’s Executors, 43 US 127, 198 (1844).

23 Vidal et al. v. Girard’s Executors, 43 US 127, 200 (1844).

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!