By David Barton1

In December 2008 following the election of Barack Obama as president, noted atheist Michael Newdow filed suit to prohibit religious acknowledgments or activities from being part of the inaugural ceremonies, specifically seeking to halt the inclusion of “So help me God” as part of the presidential oath as well as halt inaugural prayers by clergy.2

Newdow has an established record of bringing suits to eradicate long-standing public religious practices, including to:

- remove “under God” from the Pledge of Allegiance3

- eliminate “In God We Trust” (the National Motto) from coins and currency4

- prohibit California textbooks from mentioning Biblical events found in Genesis 1-35

- exclude clergy prayers from presidential inaugurations6

- reverse the time-honored tax exemptions for housing provided by churches to clergy7

- abolish chaplains hired by Congress8

Newdow insists that his quest for a completely secular public square is based on constitutional mandates, Founding Fathers’ intent, and American history. Regarding the latter, in his 2008 lawsuit, Newdow claimed that the use of the phrase “So help me God” in presidential oaths was of relatively recent origin – that George Washington had not used the phrase and that it did not become part of legal oaths, especially for presidents, until the inauguration of President Chester A. Arthur in 1881.9 Although courts and scholars have routinely rejected Newdow’s preposterous historical assertions, this specific one, for some inexplicable reason, gained traction among some media and academics, pitting them against many distinguished historical authorities.

The Chief Historian of the United States Capitol Historical Society, the Library of Congress, the U. S. Supreme Court (and numbers of its Justices), the Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies, the Architect of the Capitol, and other notables have affirmed that “so help me God” is a traditional practice dating back to George Washington. Significantly, for almost two centuries, it was universally accepted that “So help me God” had actually been said as part of the official oathtaking process, but Newdow and his fellow travelers insist that everyone except themselves has been wrong for the past two centuries.10

One of those who agrees with Newdow is Matthew Goldstein, a regular writer for atheist and secularist sites. To help prove his case, he cites with approval an article by USA Today claiming that there is “no eyewitness documentation he [Washington] ever added ‘so help me God’.”11 (So USA Today is now an authoritative historical source? Really?) Other secularist voices have joined the chorus, including attorney/writer Jim Bendat, who claims that George Washington’s use of “So help me God” is a “legend”;12 Professor Peter Henriques of George Mason University calls it a “myth,” adding that any such claim to the contrary “is almost certainly false”;13 and Charles Haynes of the First Amendment Center says that not only is it a “popular myth” but also that it’s time to completely get rid of “So help me God” as part of the oath.14

What is the historical basis for claiming that George Washington did not say “So help me God” as part of the presidential oath? According to Newdow and other critics, no records of the day specifically show Washington reciting the phrase, therefore he did not say it.

Numerous historical documents and practices disproving Newdow’s claim will be shown below, but first consider the historical unreasonableness of claiming that someone did not do something unless it is specifically written that he did so. Even Wikipedia characterizes this type of logic as an “appeal to ignorance” – an approach asserting that something is false only because it has not been proven true – that the lack of evidence for one view is substitutionary proof that another view is true.15

Consider all the inaugural absurdities that can be “proven” under the approach taken by Newdow. For example, since there is no detailed record that President James Monroe did not launch into a string of profanities at his inauguration, then he certainly must have done so; and since no one wrote on Inauguration Day 1825 that the sun rose in the east and set in the west, then it must have been otherwise. These scenarios are ridiculous, but they illustrate the inherent fallacies in the methodology used by Newdow.

Three specific strands of historical evidence will be presented below that demonstrate the absurdity of the modern claims. First, at least seven different religious activities were part of the first inauguration, thus the proceedings were indisputably heavily religiously-permeated. Second, the entirety of American legal practice at that time, including the specific stipulations of statutory law, required the phrase “So help me God” be part of any oath administered by or to government officials. Third, Washington himself, and numerous other Founding Fathers, repeatedly affirmed that an oath of office was a religious act; they explicitly rejected any notion that an oath was secular.

1. RELIGIOUS ACTIVITIES AT GEORGE WASHINGTON’S INAUGURATION

Constitutional experts abounded in 1789 at America’s first presidential inauguration. Not only was the inauguree a signer of the Constitution but one fourth of the members of the Congress that organized and directed his inauguration had been delegates with him to the Constitutional Convention that produced the Constitution.16 Furthermore, this very same Congress also penned the First Amendment and its religious clauses. Because Congress, perhaps more than any other, certainly knew what was constitutional, the religious activities that were part of the first inauguration may well be said to have had the approval and imprimatur of the greatest congressional collection of constitutional experts America has ever known.

That inauguration occurred in New York City, which served as the nation’s capital during the first year of the new federal government. The preparations had been extensive; everything had been well planned.

The papers reported on the first inaugural activity:

[O]n the morning of the day on which our illustrious President will be invested with his office, the bells will ring at nine o’clock, when the people may go up to the house of God and in a solemn manner commit the new government, with its important train of consequences, to the holy protection and blessing of the Most High. An early hour is prudently fixed for this peculiar act of devotion and . . . is designed wholly for prayer.17

As subsequent activities progressed, things seemed to be proceeding smoothly, but as the parade carrying Washington by horse-drawn carriage to the swearing-in was nearing Federal Hall, it was realized that no Bible had been obtained for administering the oath, and the law required that a Bible be part of the ceremony. Parade Marshal Jacob Morton therefore hurried off and soon returned with a large 1767 King James Bible.

The ceremony was conducted on the balcony at Federal Hall; and with a huge crowd gathered below watching the proceedings, the Bible was laid upon a crimson velvet cushion held by Samuel Otis, Secretary of the Senate. New York Chancellor Robert Livingston then administered the oath of office. (He was one of the five Founders who drafted the Declaration of Independence, but had been called back to New York to help guide his state through the Revolution before he could affix his signature to the document he had helped write. Because Livingston was the highest ranking judicial official in New York, he was chosen to administer the oath of office to President Washington.)

Standing beside Livingston and Washington were many distinguished officials, including Vice President John Adams, Supreme Court Chief Justice John Jay, Generals Henry Knox and Philip Schuyler, and several others. The Bible was opened (at random) to Genesis 49;18 Washington placed his left hand upon the open Bible, raised his right, took the oath of office, then bent over and reverently kissed the Bible. Chancellor Livingston proclaimed, “It is done!” Turning to the crowd assembled below, he shouted, “Long live George Washington – the first President of the United States!” That shout was echoed and re-echoed by the crowd. Washington and the other officials then departed the balcony and went inside Federal Hall to the Senate Chamber where Washington delivered his Inaugural Address.

In that first-ever presidential address, Washington opened with a heartfelt prayer, explaining that . . .

it would be peculiarly improper to omit in this first official act my fervent supplications to that Almighty Being Who rules over the universe, Who presides in the councils of nations, and Whose providential aids can supply every human defect – that His benediction may consecrate to the liberties and happiness of the people of the United States a government instituted by themselves for these essential purposes.19

Washington’s inaugural address was strongly religious, and he called his listeners to remember and acknowledge God:

In tendering this homage [act of worship] to the Great Author of every public and private good, I assure myself that it expresses your sentiments not less than my own, nor those of my fellow-citizens at large less than either. No people can be bound to acknowledge and adore the Invisible Hand which conducts the affairs of men more than those of the United States. Every step by which they have advanced to the character of an independent nation seems to have been distinguished by some token of Providential Agency. . . . [and] we ought to be no less persuaded that the propitious [favorable] smiles of Heaven can never be expected on a nation that disregards the eternal rules of order and right which Heaven itself has ordained.20

Having finished his address, Washington offered its closing prayer:

Having thus imparted to you my sentiments as they have been awakened by the occasion which brings us together, I shall take my present leave – but not without resorting once more to the benign Parent of the Human Race in humble supplication [prayer] that . . . His Divine blessing may be equally conspicuous in the enlarged views, the temperate consultations, and the wise measures on which the success of this government must depend.21

The next inaugural activities then began – activities arranged by Congress itself when the Senate directed:

That after the oath shall have been administered to the President, he – attended by the Vice-President and members of the Senate and House of Representatives – proceed to St. Paul’s Chapel to hear Divine service.22

The House had approved the same resolution,23 so the president and Congress thus went en masse to church as an official body. As affirmed by congressional records:

The President, the Vice-President, the Senate, and House of Representatives, &c., then proceeded to St. Paul’s Chapel, where Divine Service was performed by the chaplain of Congress.24

The service at St. Paul’s was conducted by The Right Reverend Samuel Provoost – the Episcopal Bishop of New York, who had been chosen chaplain of the Senate the week preceding the inauguration.25 He performed the service according to The Book of Common Prayer, including prayers taken from Psalms 144-150 and Scripture readings and Bible lessons from the book of Acts, I Kings, and the Third Epistle of John.26

(Significantly, in his lawsuit Newdow claimed not only that “So help me God” was of recent derivation but also that the “practice of including clergy to pray at presidential inaugurations began in 1937.”27 That claim, like so many of his others, is obviously wrong: the Rev. Provoost had offered clergy-led prayers during Washington’s inaugural activities a century-and-a-half before Newdow claimed they began.)

Significantly, seven distinctly religious activities were included in this first presidential inauguration that have been repeated in whole or part in every subsequent inauguration: (1) the use of the Bible to administer the oath; (2) solemnifying the oath with multiple religious expressions (placing a hand on the Bible, saying “So help me God,” and then kissing the Bible); (3) prayers offered by the president himself; (4) religious content in the inaugural address; (5) the president calling on the people to pray or acknowledge God; (6) church inaugural worship services; and (7) clergy-led prayers.

2. THE LEGAL STATUS OF OATHS AT THE TIME OF WASHINGTON’S INAUGURATION

Significantly, long before and long after the adoption of the Constitution, the legal requirements for oathtaking specifically stipulated that “So help me God!” be part of the official oath of all legal process, whether the oaths were taken by elected officials, appointed judges, jurors, or witnesses in a court of law.

This fact is readily demonstrated by a survey of existing laws at the time – such as those of CONNECTICUT (which will be seen were reflective of what was typical in the other states). Connecticut’s original 1639 legal code governing its very first election required that elected officials were to “swear by the great and dreadful name of the everliving God . . . so help me God, in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ.”28 When new oath laws were subsequently passed in 1718, 1726, 1731, 1742, etc., all retained the same general form, including the mandatory use of “So help me God.” Those same provisions were retained long after the federal Constitution was adopted.29

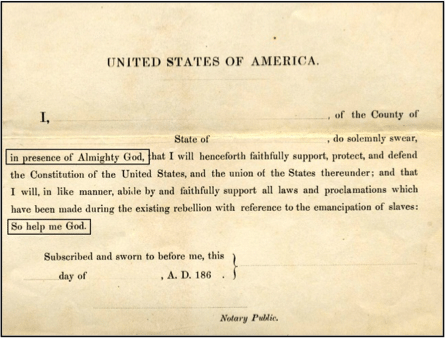

GEORGIA required that elected officials, judges, jurors, and witnesses take their oath “in the presence of Almighty God . . . so help me God,” and not only that they take their oath on the Bible but specifically “on the holy evangelists of Almighty God.”30 (Like the other states, this provision was the same long before and after the adoption of the federal Constitution.)

NORTH CAROLINA required “the party to be sworn to lay his hand upon the Holy Evangelists of Almighty God . . . and after repeating the words, ‘So help me God,’ shall kiss the Holy Gospels.”31 In SOUTH CAROLINA, officials were also required to take their “oath on the Holy Evangelists of Almighty God.”32

Other states had similar requirements, but consider those in place in NEW YORK when President Washington was sworn in by the state’s top judicial official. At that time, New York law required that “the usual mode of administering oaths” be followed (i.e., “So help me God”) and that the person taking the oath place his hand upon the Gospels and then kiss the Gospels at the conclusion of the oath.33 (Like the other states, these provisions remained the legal standard long after the inauguration.34)

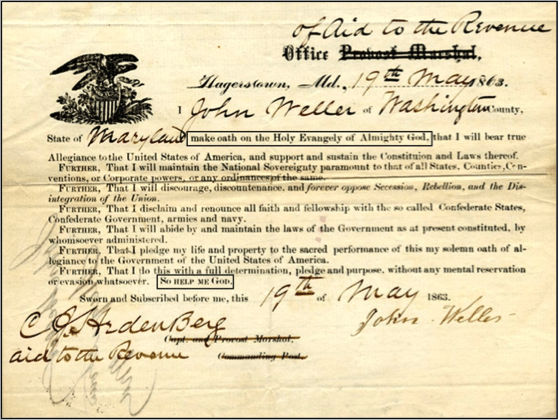

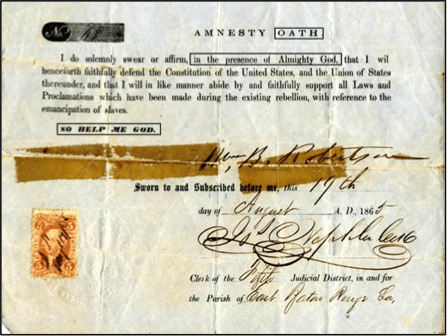

Standard oath forms, both state and federal, still in use even decades after Washington’s inauguration, retained those phrases. See some examples below – and notice that each is from a period decades prior to the time that Newdow claims the practice began:

(These are just a few of the many original oath-related documents personally owned by the author;

countless others are found in the records of the Library of Congress)

Clearly, using the phrase “So help me God” (as well as placing one’s hand on and then kissing the Bible) was established legal practice throughout the Founding Era.

No one disputes that Washington placed his hand on the Bible or that he kissed it, so why is it now claimed that he did not say “So help me God”? Are critics saying that Washington would not have done the easiest of the three legally required parts of oathtaking? Or would they prefer that officials stop saying “So help me God” but kiss the Bible instead? Their argument is ludicrous. Furthermore, the omission of “So help me God” from the oathtaking ceremony in the Founding Era would have been a clear and obvious aberration from established legal practice of the day, therefore it is the omission of that phrase rather than its inclusion that would have been particularly noticed and commented upon by observers; but such an omission was never mentioned by any witness.

3. THE FOUNDING FATHERS’ VIEWS:

WERE OATHS INHERENTLY RELIGIOUS OR INHERENTLY SECULAR?

Five locations in the U. S. Constitution address oaths to be taken by federal officials. As has already been shown, oath clauses were not a unique or original innovation of the federal Constitution but were already in use in each of the states and the national Congress long before the Constitution was written and remained in force long thereafter.

Significantly, every existing law or legal commentary from before, during, and after the writing of the Constitution unanimously affirmed that the taking of any oath by any public official was always an inherently religious activity; and numerous Framers and early legal scholars agreed (emphasis added in each quote):

[An] oath – the strongest of religious ties.35 JAMES MADISON, SIGNER OF THE CONSTITUTION

[In o]ur laws . . . by the oath which they prescribe, we appeal to the Supreme Being so to deal with us hereafter as we observe the obligation of our oaths. The Pagan world were and are without the mighty influence of this principle which is proclaimed in the Christian system.36 RUFUS KING, SIGNER OF THE CONSTITUTION, FRAMER OF THE BILL OF RIGHTS

Oaths in this country are as yet universally considered as sacred obligations.37 JOHN ADAMS, SIGNER OF THE DECLARATION, FRAMER OF THE BILL OF RIGHTS

An oath is an appeal to God, the Searcher of Hearts, for the truth of what we say and always expresses or supposes an imprecation [calling down] of His judgment upon us if we prevaricate [lie]. An oath, therefore, implies a belief in God and His Providence and indeed is an act of worship. . . . In vows, there is no party but God and the person himself who makes the vow.38 JOHN WITHERSPOON, SIGNER OF THE DECLARATION

The Constitution enjoins an oath upon all the officers of the United States. This is a direct appeal to that God Who is the avenger of perjury. Such an appeal to Him is a full acknowledgment of His being and providence.39 OLIVER WOLCOTT, SIGNER OF THE DECLARATION, GOVERNOR

According to the modern definition [1788] of an oath, it is considered a “solemn appeal to the Supreme Being for the truth of what is said by a person who believes in the existence of a Supreme Being and in a future state of rewards and punishments . . .”40 JAMES IREDELL, RATIFIER OF THE CONSTITUTION, U. S. SUPREME COURT JUSTICE APPOINTED BY GEORGE WASHINGTON

The Constitution had provided that all the public functionaries of the Union not only of the general [federal] but of all the state governments should be under oath or affirmation for its support. The homage of religious faith was thus superadded to all the obligations of temporal law to give it strength.41 JOHN QUINCY ADAMS, PRESIDENT

“What is an oath?” . . . [I]t is founded on a degree of consciousness that there is a Power above us that will reward our virtues or punish our vices. . . . [O]ur system of oaths in all our courts, by which we hold liberty and property and all our rights, are founded on or rest on Christianity and a religious belief.42 DANIEL WEBSTER, “DEFENDER OF THE CONSTITUTION”

There are many other similar declarations.43 And America’s leading legal authorities and reference sources likewise affirmed that taking an oath was a religious activity. For example, in 1793, Zephaniah Swift, author of America’s first law book, declared:

An oath is a solemn appeal to the Supreme Being that he who takes it will speak the truth, and an imprecation of His vengeance if he swears false.44

In 1816, Chancellor James Kent, considered to be one of the two “Fathers of American Jurisprudence,” noted that an oath of office was a “religious solemnity” and that to administer an oath was “to call in the aid of religion.”45

In 1828, Founding Father Noah Webster, an attorney and a judge, defined an “oath” as:

A solemn affirmation or declaration made with an appeal to God for the truth of what is affirmed. The appeal to God in an oath implies that the person imprecates [calls down] His vengeance and renounces His favor if the declaration is false, or (if the declaration is a promise) the person invokes the vengeance of God if he should fail to fulfill it.46

In 1834, a popular judicial handbook declared:

Judges, justices of the peace, and all other persons who are or shall be empowered to administer oaths shall . . . require the party to be sworn to lay his hand upon the Holy Evangelists of Almighty God in token of his engagement to speak the truth as he hopes to be saved in the way and method of salvation pointed out in that blessed volume; and in further token that if he should swerve from the truth, he may be justly deprived of all the blessings of the Gospels and be made liable to that vengeance which he has imprecated on his own head; and after repeating the words, “So help me God,” shall kiss the holy Gospels as a scale of confirmation to said engagement.47

In 1839, Bouvier’s Law Dictionary, considered one of America’s most popular law dictionaries (and still widely used by courts even today), stated that an oath was:

[A] religious act by which the party invokes God not only to witness the truth and sincerity of his promise but also to avenge his imposture or violated faith. . . . . Oaths are taken in various forms; the most usual is upon the Gospel by taking the book [the Bible] in the hand; the words commonly used are, “You do swear that,” &c., “so help you God,” and then kissing the book. . . . Another form is by the witness or party promising, holding up his right hand while the officer repeats to him, “You do swear by Almighty God, the searcher of hearts, that,” &c., “And this as you shall answer to God at the great day.”48

In 1854, the House Judiciary Committee affirmed:

Laws will not have permanence or power without the sanction of religious sentiment – without a firm belief that there is a Power above us that will reward our virtues and punish our vices.49

Early legal historian James Tyler penned an extensive work on the historical and legal nature and form of oaths and concluded:

The object of the form of adjuration [oath] should be to point out this: to show that we are not calling the attention of God to man, but the attention of man to God. . . . [T]he mode now universally adopted among us is imprecatory – the invoking of God’s vengeance in case we do not fulfill our engagement to speak the truth, or perform the specific duty, “So help me God.”50

Significantly, courts had agreed with the conclusions of the Founding Fathers and early legal authorities, issuing numerous declarations making the same affirmations.51 Even school textbooks in that day taught students that in the American constitutional process, an oath was always a religious act.52

Additional sources could be cited, but the evidence is unequivocal that the taking of an oath was universally considered to be a religious activity. For this reason a secular oath was not admissible before a court of law,53 and well into the latter half of the twentieth century, even the U. S. Supreme Court continued to reaffirm the religious nature of oaths.54 After all, as one early court noted, to remove the religious meaning of oaths and to exclude the Bible on which they were sworn would make “an oath . . . a most idle ceremony.”55

Returning to Washington’s inauguration, he took the presidential oath of office as prescribed in Article II of the Constitution – an oath he had helped write:

I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will faithfully execute the office of President of the United States, and will to the best of my ability, preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States.

Why was the phrase “So help me God” not specifically included in the Constitution as part of the prescribed wording? Because to have added it would have been redundant: that phrase, as well as placing one’s hand on and then kissing the Bible, was already standard legal practice; there was no reason to duplicate in the Constitution what was already universally required both by law and tradition.

Significantly, Washington was so concerned that the oathtaking process remain inherently religious that in his famous Farewell Address at the end of his presidency, he pointedly warned Americans to never let it become secular:

[W]here is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths . . . ?56

Endnotes

1 David Barton is the President of WallBuilders, a national pro-family organization that presents America’s forgotten history and heroes, with an emphasis on our moral, religious and constitutional heritage. Barton is the author of numerous best-selling books, with the subjects being drawn largely from his massive library of tens of thousands of original writings from the Founding Era. His exhaustive research has rendered him an expert in historical and constitutional issues. He serves as a consultant to state and federal legislators, has participated in several cases at the Supreme Court, was involved in the development of History/Social Studies standards for public schools in numerous states, and has helped produce history textbooks now used in schools across the nation. David has received numerous national and international awards, including multiple Who’s Who in Education, DAR’s Medal of Honor, and the George Washington Honor Medal from the Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge.

2 Newdow v. Roberts, 603 F.3d 1002, Ct. of Appeals, Dist. of Columbia (2010).

3 Elk Gove Unified School District v. Newdow, 542 U.S. 1 (2004).

4 Newdow v. Lefevre, 598 F.3d 638, Ct. of Appeals, 9th Cir. (2010).

5 “Michael Newdow Joins CAPEEM’s Legal Team,” December 17, 2007, Capeem.org.

6 Newdow v. Roberts, 603 F.3d 1002, Ct. of Appeals, Dist. of Columbia (2010).

7 “FFRF v. Geithner Parsonage Exemption,” Freedom from Religion Foundation, accessed on November 23, 2011.

8 Newdow v. Eagen, 309 F. Supp. 2d 29, Dist. Court of Columbia (2004).

9 See, for example, Newdow v. Roberts, Complaint 1:08-cv-02248-RBW (2008). See also Cathy Lynn Grossman, “No proof Washington said ‘so help me God’ – will Obama,” USA Today, January 9, 2009.

10 “So Help Me God in Presidential Oaths,” nonbeliever.org, accessed November 23, 2011.

11 Cathy Lynn Grossman, “No proof Washington said ‘so help me God’ — will Obama?” January 9, 2009, USA Today.

12 Jim Bendat, Democracy’s Big Day: The Inauguration of our President 1789-2009 (New York: iUniverse Star, 2008), 21.

13 Peter R. Henriques, “ ‘So Help Me God’: A George Washington Myth that Should Be Discarded,” January 12, 2009, History News Network.

14 Charles C. Haynes, “Inside the First Amendment: Are ‘so help me God,’ inaugural prayer still appropriate?” January 18, 2009, First Amendment Center.

15 “Argument from Ignorance,” Wikipedia, accessed November 23, 2011.

16 Significantly, many of the U. S. Senators at the first Inauguration had been delegates to the Constitutional Convention that framed the Constitution including William Samuel Johnson, Oliver Ellsworth, George Read, Richard Bassett, William Few, Caleb Strong, John Langdon, William Paterson, Robert Morris, and Pierce Butler; and many members of the House had been delegates to the Constitutional Convention, including Roger Sherman, Abraham Baldwin, Daniel Carroll, Elbridge Gerry, Nicholas Gilman, Hugh Williamson, George Clymer, Thomas Fitzsimmons, and James Madison.

17 The Daily Advertiser (New York: April 23, 1789), 2.

18 Clarence W. Bowen, The History of the Centennial Celebration of the Inauguration of George Washington (New York, D. Appleton & Co., 1892), 52, Illustration; “The George Washington Inaugural Bible,” National Park Service, accessed June 24, 2025.

19 The Debates and Proceedings in the Congress of the United States, ed. Joseph Gales (Washington: Gales & Seaton, 1834), I:27; George Washington, Messages and Papers of the Presidents, ed. James D. Richardson (Washington, D.C.: 1899), 1:44-45, April 30, 1789.

20 Debates and Proceedings, ed. Gales (1834), I:27-29, April 30, 1789.

21 Debates and Proceedings, ed. Gales (1834), I:27-29, April 30, 1789.

22 Debates and Proceedings, ed. Gales (1834), I:25, April 27, 1789.

23 Debates and Proceedings, ed. Gales (1834), I:241, April 29, 1789.

24 Debates and Proceedings, ed. Gales (1834), I:29, April 30, 1789.

25 Bowen, History of the Centennial (1892), 54; “About the Senate Chaplain,” United States Senate, accessed June 24, 2025.

26 Book of Common Prayer (Oxford: W. Jackson & A. Hamilton, 1784), s.v., April 30th.

27 Newdow v. Roberts, Complaint 1:08-cv-02248-RBW (2008).

28 R.R. Hinman, A.M., Letters From the English Kings and Queens, Charles II, James II, William and Mary, Anne, George II, &C., To the Governors of the Colony of Connecticut, Together With the Answers Thereto, From 1635 to 1749; And Other Original, Ancient, Literary and Curious Documents, Compiled From Files and Records in the Office of the Secretary of the State of Connecticut (Hartford: John B. Eldredge, Printer, 1836), 26-28.

29 The Public Statute Laws of the State of Connecticut (Hartford: Hudson and Goodwin, 1808), 535, Title CXXII: Oaths, Ch. 1, Sec. 6, law passed in May, 1742; 540, Title CXXII: Oaths, Ch. 1, Sec. 25, law passed in May, 1726; 541, Title CXXII: Oaths, Ch. 1, Sec. 30 & 32, law passed in May, 1718.

30 “An Act for the case of Dissenting Protestants, within this province, who may be scrupulous of taking an oath, in respect to the manner and form of administering the same,” passed December 13, 1756, Oliver H. Prince, A Digest of the Laws of the State of Georgia (Milledgeville: Grantland & Orme, 1822), 3.

31 “Oaths and Affirmations. 1777,” John Haywood, A Manual of the Laws of North Carolina (Raleigh: J. Gales, 1814), 34.

32 Joseph Brevard, An Alphabetical Digest of the Public Statue Law of South Carolina (Charleston: John Hoff, 1814), II:86, “Oaths-Affirmations.”

33 Laws of the State of New- York (New York: Thomas Greenleaf, 1798), 21, “Chap. XXV: An Act to dispense with the usual mode of administering oaths, in favor of persons having conscientious scruples respecting the same, Passed 1st of April, 1778”; James Parker, Conductor Generalis: Or the Office, Duty and Authority of the Justices of the Peace (New York: John Patterson, 1788), 302-304, “Of oaths in general.”

34 George C. Edward, A Treatise on the Powers and Duties of Justices of the Peace and Town Officers, in the State of New York (Ithaca: Mack, Andrus & Woodruff, 1836), 91, “Of the proceedings on the trial.”

35 James Madison, observations by Madison on the vices of the political system of the United States, April 23, 1787, The Writings of James Madison, ed. Gaillard Hunt (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1901), 2:367.

36 Rufus King, October 30, 1821, Reports of the Proceedings and Debates of the Convention of 1821, Assembled for the Purpose of Amending The Constitution of the State of New York (Albany: E. and E. Hosford, 1821), 575.

37 John Adams to the Officers of the First Brigade of the Third Division of the Militia of Massachusetts, October 11, 1798, The Works of John Adams, ed. Charles Francis Adams (Boston: Little, Brown and company, 1854), IX:229.

38 John Witherspoon, “Lectures on Moral Philosophy,” The Works of John Witherspoon (Edinburgh: J. Ogle, 1815), VII:139, 142.

39 Oliver Wolcott, January 9, 1788, Jonathan Elliot, The Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution (Washington: Printed for the Editor, 1836), II:202.

40 James Iredell, July 30, 1788, Elliot, Debates (1836), IV:196.

41 John Quincy Adams, The Jubilee of the Constitution (New York: Samuel Colman, 1839), 62.

42 Daniel Webster, Mr. Webster’s Speech in Defense of the Christian Ministry and in Favor of the Religious Instruction of the Young, Delivered in the Supreme Court of the United States, February 10, 1844, in the Case of Stephen Girard’s Will (Washington: Gales and Seaton, 1844), 43, 51.

43 See, for example, Zephaniah Swift, A System of Laws of the State of Connecticut (Windham: John Byrne, 1796), II:238; Jacob Rush, Charges and Extracts of Charges on Moral and Religious Subjects (Philadelphia Geo Forman, 1804), 34-35, 37, 40; Daniel Webster, Speech in Defence of the Christian Ministry (1844), 43, 5; From an original document in our possession, executed by John Hart on March 24, 1757; Updegraph v. The Commonwealth, 11 S. & R. 394 (Sup. Ct. Pa. 1824); City Council of Charleston v. S.A. Benjamin, 2 Strob. 508, 522-524 (Sup. Ct. S.C. 1846).

44 Swift, System of Laws (1796), II:238.

45 James Kent, Memoirs and Letters of James Kent, ed. William Kent (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1898), 164.

46 Noah Webster, A Dictionary of the English Language (New York: S. Converse, 1828), s.v. “oath.”

47 James Coffield Mitchell, The Tennessee Justice’s Manual and Civil Officer’s Guide (Nashville: Mitchell and C. C. Norvell, 1834), 457-458.

48 John Bouvier, A Law Dictionary Adapted to the Constitution and Laws of the United States of America, and of the Several States of the American Union (Philadelphia: T. & J. W. Johnson, 1839), s.v. “oath.”

49 “Rep. No. 124. Chaplains in Congress and in the Army and Navy,” March 27, 1854, Reports of Committees of the House of Representatives Made During the First Session of the Thirty-Third Congress (Washington: A. O. P. Nicholson, 1854), 8.

50 James Endell Tyler, Oaths; Their Origin, Nature, and History (London: John W. Parker, 1834), 14, 57.

51 See, for example, People v. Ruggles, 8 Johns 545, 546 (1811); Commonwealth v. Wolf, 3 Serg. & R. 48, 50 (1817); City Council of Charleston v. S.A. Benjamin, 2 Strob. 508, 522-524 (Sup. Ct. S.C. 1846); and many others.

52 William Sullivan, The Political Class Book (Boston: Richardson, Lord, and Holbrook, 1831), 139, §392.

53 Alexis de Tocqueville, The Republic of the United States of American and Its Political Institutions, Reviewed and Examined, trans. Henry Reeves (Garden City, NY: A. S. Barnes & Co., 1851), I:334, 344n. See also Daniel Webster, Speech in Defence of the Christian Ministry (1844), 43; Joseph Story, Life and Letters of Joseph Story, ed. William W. Story (Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown, 1851), II:8-9; Swift, System of Laws (1796), II:238.

54 Abington v. Schempp, 374 U.S. 203 (1963).

55 Updegraph v. The Commonwealth, 11 S. & R. 394 (Sup. Ct. Pa. 1824).

56 George Washington, Address of George Washington, President of the United States . . . Preparatory to His Declination (Baltimore: George and Henry S. Keatinge, 1796), 23.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!