All arguments making Christopher Columbus a villain comparable with Adolf Hitler1 or Saddam Hussain 2 start with the premise that the world he discovered was populated by peaceful inhabitants who lived in a golden age. It was only with the introduction of the white man, critics claim, that this paradise was destroyed by the tyrannical oppression perpetuated by the European Christians.

The current romanticized presentation of the native cultures is the underlying assumption which permits the narrative that Columbus was a villain. Academics push this to justify tearing down statues of the explorer and removing his name from the calendar. Proponents of the alternative to Columbus Day—which they call Indigenous People’s Day—are also proponents of alternative history.

Howard Zinn, in his massively influential yet famously inaccurate work A People’s History of the United States, propagated this myth of the noble savage:

So, Columbus and his successors were not coming into an empty wilderness, but into a world which in some places was as densely populated as Europe itself, where the culture was complex, where human relations were more egalitarian than in Europe, and where the relations among men, women, children, and nature were more beautifully worked out than perhaps any place in the world.3

According to Zinn (and most if not all of the modern outcry against Columbus can be traced to his book), the indigenous people were far more advanced in their social morality than the Europeans. This, of course, leads to the conclusion that the white man was (and still is) a racist tyrant oppressing whomever he might. This leads to the conclusion that America was (and still is) one of the worst nations in all of history.

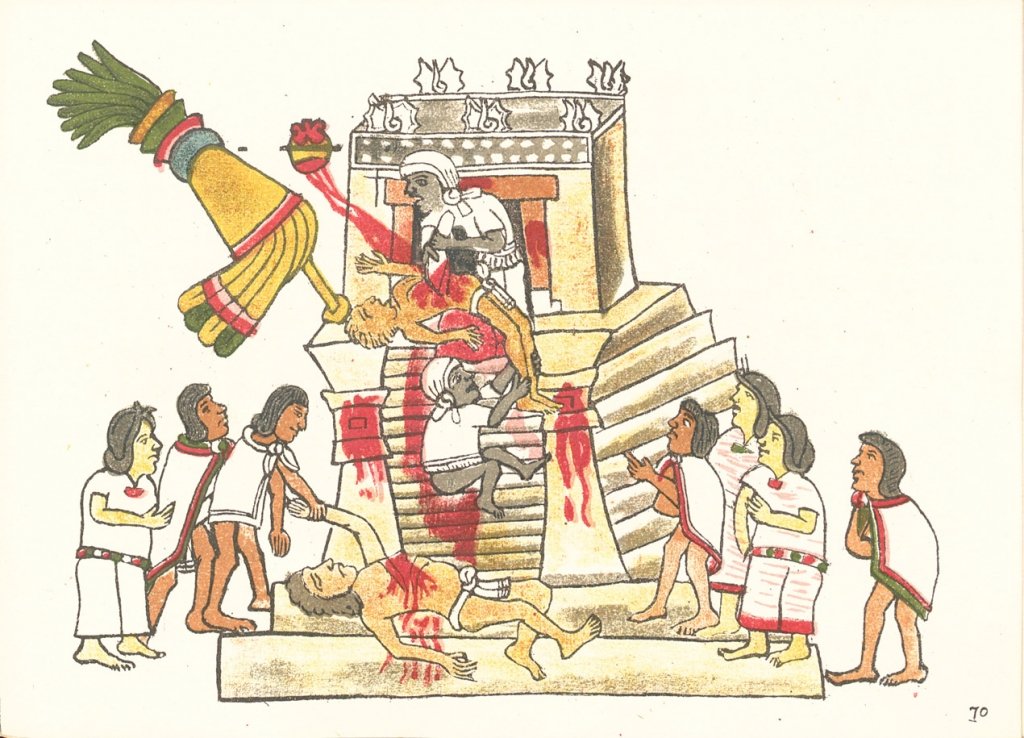

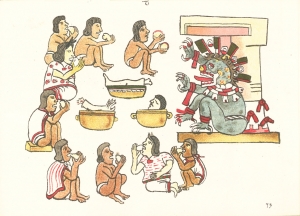

What Zinn and his followers fail to account for are the facts. The world Columbus discovered was full of slavery, murder, genocide, sodomy, sexual exploitation, and general barbarity. Zinn only mentions the famous atrocities of the Aztec culture in passing to say that, “the cruelty of the Aztecs, however, did not erase a certain innocence.”4 Let’s take a look at the “certain innocence” prevalent in the cultures encountered by Columbus and the other pre-Columbian natives.

Although the first tribe (led by the chieftain Guacanagari) was extremely friendly to Columbus—so much so that the Columbus even declared that, “a better race there cannot be, and both the people and the lands are in such quantity that I know not how to write it”5—they were not the pacifistic society often portrayed. This first tribe was part of the Taino community which occupied many of the islands in the West Indies. They held those islands, however, because they themselves had conquered, driven out, and replaced the earlier Siboney culture. The Taino domination was so complete that Columbus only ever encountered one such Siboney native.6

The Taino’s warrior culture was noticeably lacking when compared to the truly savage culture of the Carib (or Canib) tribes. These indigenous peoples (from whose name we derive both the words “Caribbean” and “cannibal”) were feared by the Taino because of the constant raids and attacks. During his first voyage, the Taino told Columbus about “extremely ferocious…eaters of human flesh” who “visit all the Indian islands, and rob and plunder whatever they can.”7

Columbus and his shipmates had extensive encounters with the Caribs during the subsequent voyages. The things they saw corresponded exactly with the description giving by their Taino friends, and many other atrocities which they had failed to mention.

For instance, the Caribs would spend up to a decade plundering any particular island until they completely depopulated it through slavery and cannibalism.8 Specifically, on these campaigns they would cannibalize the men and enslave the women and young boys. One of Columbus’s crew member left us with a description of what the Caribs would do to their captives, saying that he found:

twelve very beautiful and very fat women from 15 to 16 years old, together with two boys of the same age. These had the genital organ cut to the belly; and this we thought had been done in order to prevent them from meddling with their wives or maybe to fatten them up and later eat them. These boys and girls had been taken by the above mentioned Caribs;9

The testimony by the Taino of cannibalism was confirmed by the amount of human bones and even cooking limbs found in the villages.10 Another shipmate on the voyage, the lead doctor, also related in depth the terrible acts of the Caribs. He explained:

In their wars upon the inhabitants of the neighboring islands, these people capture as many of the women as they can, especially those who are young and handsome, and keep them as body servants and concubines; and so great a number do they carry off, that in fifty houses we entered no man was found, but all were women. Of that large number of captive females more than twenty handsome women came away voluntarily with us.

When the Caribbees take any boys as prisoners of war, they remove their organs, fatten the boys until they grow to manhood and then, when they wish to make a great feast, they kill and eat them, for they say the flesh of boys and women is not good to eat. Three boys thus mutilated came fleeing to us when we visited the houses.11

The same doctor describes another instance where they came to a Carib slave camp and:

As soon as these women learned that we abhor such kind of people because of their evil practice of eating human flesh, they felt delighted…. These captive women told us that the Carribbee men use them with such cruelty as would scarcely be believed; and that they eat the children which they bear to them, only bringing up those which they have by their native wives. Such of their male enemies as they can take away alive, they bring here to their homes to make a feast of them, and those who are killed in battle they eat up after the fighting is over. They claim that the flesh of man is so good to eat that nothing like it can be compared to it in the world; and this is pretty evident, for of the human bones we found in their houses everything that could be gnawed had already been gnawed, so that nothing else remained of them but what was too hard to be eaten. In one of the houses we found the neck of a man undergoing the process of cooking in a pot, preparatory for eating it.

This authentic eyewitness picture of the indigenous people is radically different that the one presented by Zinn. If this is what he means by “certain innocence” what does guilt looks like? Remember, these are the people of whom he proclaimed that their “relations among men, women, children, and nature were more beautifully worked out than perhaps any place in the world.” It may comes as a shock to Zinn, but no one ought to consider slavery, sexual exploitation, and infant cannibalism as “beautifully worked out.”

This is the New World which Columbus discovered. It wasn’t filled with friendly, peaceful, tribes, but people numerous and warlike. It is against this backdrop that we must evaluate the actions of Columbus and not the fabricated history created by fake historians like Howard Zinn and his followers.

Endnotes

1 Russel Means, quoted by Dinesh D’Souza in “The Crimes of Christopher Columbus,” First Things, November 1995.

2 Eric Kasum, “Columbus Day? True Legacy: Cruelty and Slavery,” Huffington Post, October 10, 2010.

3 Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (New York: Harper Collins, 2015), 21.

4 Howard Zinn, A People’s History of the United States (New York: Harper Collins, 2015), 11.

5 Christopher Columbus, The Journal of Christopher Columbus, trans. Clements Markham (London: Hakluyt Society, 1893), 131.

6 Samuel Morrison, Admiral of the Ocean Sea (New York: MJF Books, 1970), 464.

7 Christopher Columbus, “Letter sent by Columbus to Chancellor of the Exchequer, respecting the Islands found in the Indies,” Select Letters of Christopher Columbus, trans. R. H. Major (London: Hakluyt Society, 1870), 14.

8 “Michele de Cuneo’s Letter on the Second Voyage, 28 October 1495,” Journals and Other Documents on the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, trans. Samuel Morrison (New York: Heritage Press, 1963), 219.

9 “Michele de Cuneo’s Letter on the Second Voyage, 28 October 1495,” Journals and Other Documents, trans. Morrison (1963), 211-212.

10 “Letter of Dr. Diego Alvarez Chanca,” Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1907), 48:438, 440.

11 “Letter of Dr. Diego Alvarez Chanca,” Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections (Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 1907), 48:442.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!