COVID Outbreak

With the worldwide Coronavirus outbreak in 2020 many people have been shocked at “the unprecedented steps government leaders have taken to contain the coronavirus.”[1] Groups of people are no longer allowed to assemble, Churches have been closed, theaters and “non-essential” businesses have been shuttered—all by order of the government, whether local, state, or federal. Rushes on items like toilet paper, milk, and hand sanitizer led to nationwide shortages, and companies with production based in foreign nations have had their factories nationalized or exports restricted, compounding the issues.[2]

The economic damages from the virus were incomprehensibly immense. Since the start of forcible shutdowns of “non-essential” businesses nearly 16.8 million Americans lost their jobs either temporarily or permanently.[3] At one-point economic forecasters worried that the US GDP could drop nearly 40% in the second quarter,[4] and international financial groups predicted anywhere from a Great Recession to a Great Depression level of crisis.[5] Across the globe, 81% of workers “have had their workplace fully or partly closed.”[6]

Civil Liberties

Such events led many to wonder about the effects which this pandemic will have upon the civil liberties in America. Some have cheered the expansion of government, exclaiming that “there are no libertarians in an epidemic,”[7] and that Americans “need efficient, talented, thriving bureaucracies.”[8] Others warn that “big government has hurt our ability to deal with this crisis.”[9] Lawmakers have seen the pandemic as an opportunity to push their policies and agendas, while media outlets hope that Americans “will not only come to rely on the policies, but begin to see them as a right.”[10]

These varying predictions, imaginations, and hopes all lead towards the underlying questions—what will America look like after this is all over? Will our political institutions even be recognizable? Can free markets survive? Will the Constitution lay shredded on the floor? Will there even be an America? What will become of this “last best hope of earth”?[11]

While only time will truly answer these questions, history provides us a way to anticipate what could happen and what Americans need to be on guard against. The Bible explains that, “there is nothing new under the sun” (Ecclesiastes 1:9). History hold answers to the problems of the present. So let us, “remember the days of old; consider the years of many generations; ask your father, and he will show you, your elders, and they will tell you” (Deuteronomy 32:7).

Spanish Flu

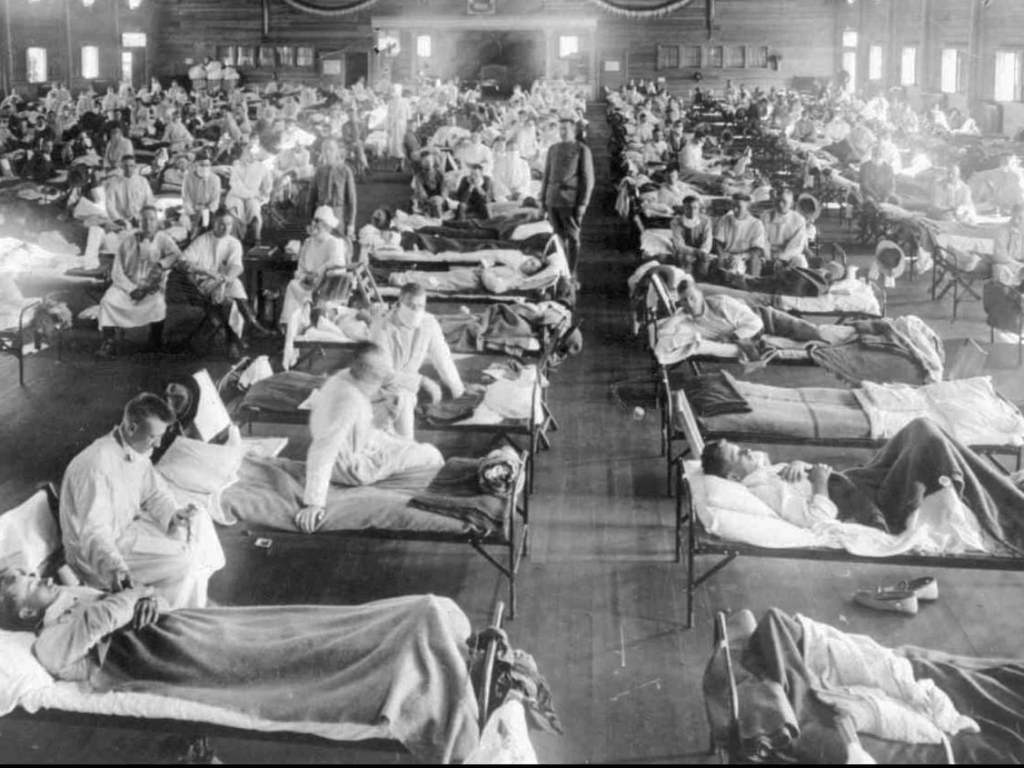

It might come as a surprise, but this is not the first time America has been through such a pandemic. For all the talk of quarantines, closures, and shutdowns being unprecedented there is a remarkable amount of precedent. Perhaps the situation which most parallels our current situation is the deadly Spanish Flu outbreak of 1918-1919. Quickly spreading, deadly, and confounding to the science of the time, it eventually claimed 675,000 lives in America alone. And upwards of 50 million globally.[12]

It might come as a surprise, but this is not the first time America has been through such a pandemic. For all the talk of quarantines, closures, and shutdowns being unprecedented there is a remarkable amount of precedent. Perhaps the situation which most parallels our current situation is the deadly Spanish Flu outbreak of 1918-1919. Quickly spreading, deadly, and confounding to the science of the time, it eventually claimed 675,000 lives in America alone. And upwards of 50 million globally.[12]

In response to the seriousness of this new strain of flu the local and state governments across the country enacted many different guidelines and regulations to slow the spread. For example, Wisconsin approached the situation with, “one of the most comprehensive anti-influenza programs in the nation.”[13] By October of 1918 the state ordered the closure of all public institutions such as schools in accordance with the suggestion of the U.S. Surgeon General. Going on to then command localities, “to immediately close all schools, theaters, moving picture houses, other places of amusement and public gatherings for an indefinite period of time.”[14] This included churches as well. When one city refused to immediately comply the state officials threatened to “quarantine the entire town.”[15] When the hospitals ran out of beds for patients, emergency facilities were opened and large numbers of charities and volunteers filled in as nurses and sources of financial aid.[16]

Shutdowns & the Spanish Flu

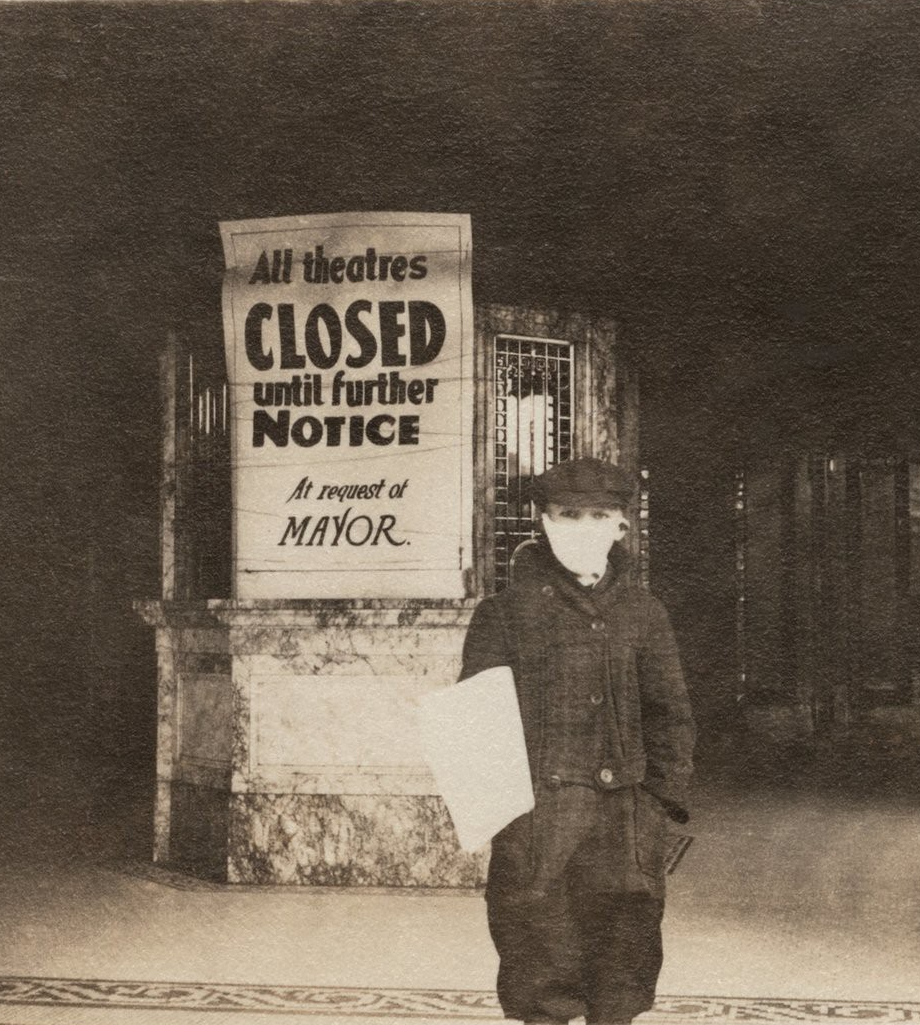

From a city perspective, San Diego instituted many similar restrictions. Once confirmed cases appeared, the local government “closed all public amusements and facilities indefinitely.”[17] San Diego then authorized the police to enforce the shutdown of, “theaters, motion picture houses, churches, dance halls, swimming pools, gymnasiums, schools, bath houses, auction sales, billiard and pool halls, libraries, women’s weekly club meetings, and outdoor meetings.”[18] Masks were to be worn and instructions were issued so that people could make them at home. When cases began to decline the regulations were loosened, but thereafter another wave arrived and the health board demanded more closures.

This time, however, businesses and citizens fought back, frustrated that after five weeks of being closed by the government they were once again to shut down. Eventually, the statewide California Board of Health forcibly ordered, “a quarantine of theaters, churches, schools, and other public places and gatherings.”[19] In this second wave of government-mandated closures the order “only exempted businesses providing essential services.”[20] Schools did not reopen until the following year.[21]

This time, however, businesses and citizens fought back, frustrated that after five weeks of being closed by the government they were once again to shut down. Eventually, the statewide California Board of Health forcibly ordered, “a quarantine of theaters, churches, schools, and other public places and gatherings.”[19] In this second wave of government-mandated closures the order “only exempted businesses providing essential services.”[20] Schools did not reopen until the following year.[21]

Elsewhere, other places followed suit. San Antonio closed “all public gathering places, including schools, churches, and theaters,” telling stores not to hold sales and even banning jury trials and public funerals.[22] Citizens were instructed to, “avoid contact with other people as far as possible.…keep your hands clean and keep them out of your mouth.”[23] In Las Vegas they bemoaned that, “nobody knows how long it will last, but until further notice the churches, schools, clubs, and other places of public gathering will be closed.”[24]

Likewise in Seattle they closed “places of amusement” in addition to “schools, churches, theaters, pool halls, and card rooms.”[25] Seattle is also noted for inventing and administering their own vaccine and commanding people to wear masks with police enforcement.[26] In total:

“The flu caused a six-week closure of churches, theaters, many places of business, and the University of Washington. It threatened to cripple wartime industry at a time of national emergency. It disrupted transportation and communication and taxed a medical community already depleted by conditions of war. It squelched campaign debate before the 1918 elections.…the second wave of flu further destabilized an already shaken society. The beginnings of the disillusionment that characterized the immediate postwar period might well be found in the flu epidemic and its aftermath.”[27]

Economic Ramifications

Economically, the ramifications of the closures were dramatic and damaging. In Little Rock, Arkansas, business reported that there was a 40% to 70% decrease in business, and on average those establishments suffered about $10,000 of actual loss per day during the pandemic (over $170,000 in 2020 dollars).[28] In Memphis and the across of Tennessee, mines and industrial plants struggled to maintain their workforce and even the telephone companies had to begin censoring “unnecessary” calls due to the loss of capacity.[29] Overall, “many businesses, especially those in the service and entertainment industries, suffered double-digit losses in revenue.”[30]

Clearly the Spanish flu had drastic effects upon the nation throughout its duration. From the churches, to the economy, to the election, nothing seemed to be left uninfected by the disease which had covered the country. Literally tucked in between death notices of people dying it was noted during the 1918 midterms that the, “election day passed off quietly here.”[31]

1920 Presidential Election

After all of this the Presidential Election of 1920 soon began to loom over the horizons. The political effects of the Spanish Flu continued to be felt all the way up to the presidential election of 1920. After a global war, deadly pandemic with strict government regulations, and an increasing level of commitment overseas, Americans seemed ready for a different direction.

On top of that, during the months leading up to the election a massive economic recession came on the back of the Armistice and the lingering worries for the Spanish Flu. The then Vice-Presidential candidate Calvin Coolidge recalled later that:

“The country was already feeling acutely the results of deflation. Business was depressed. For months following the Armistice we had persisted in a course of much extravagance and reckless buying. Wages had been paid that were not earned. The whole country, from the national government down, had been living on borrowed money. Pay day had come, and it was found our capital had been much impaired.”[32]

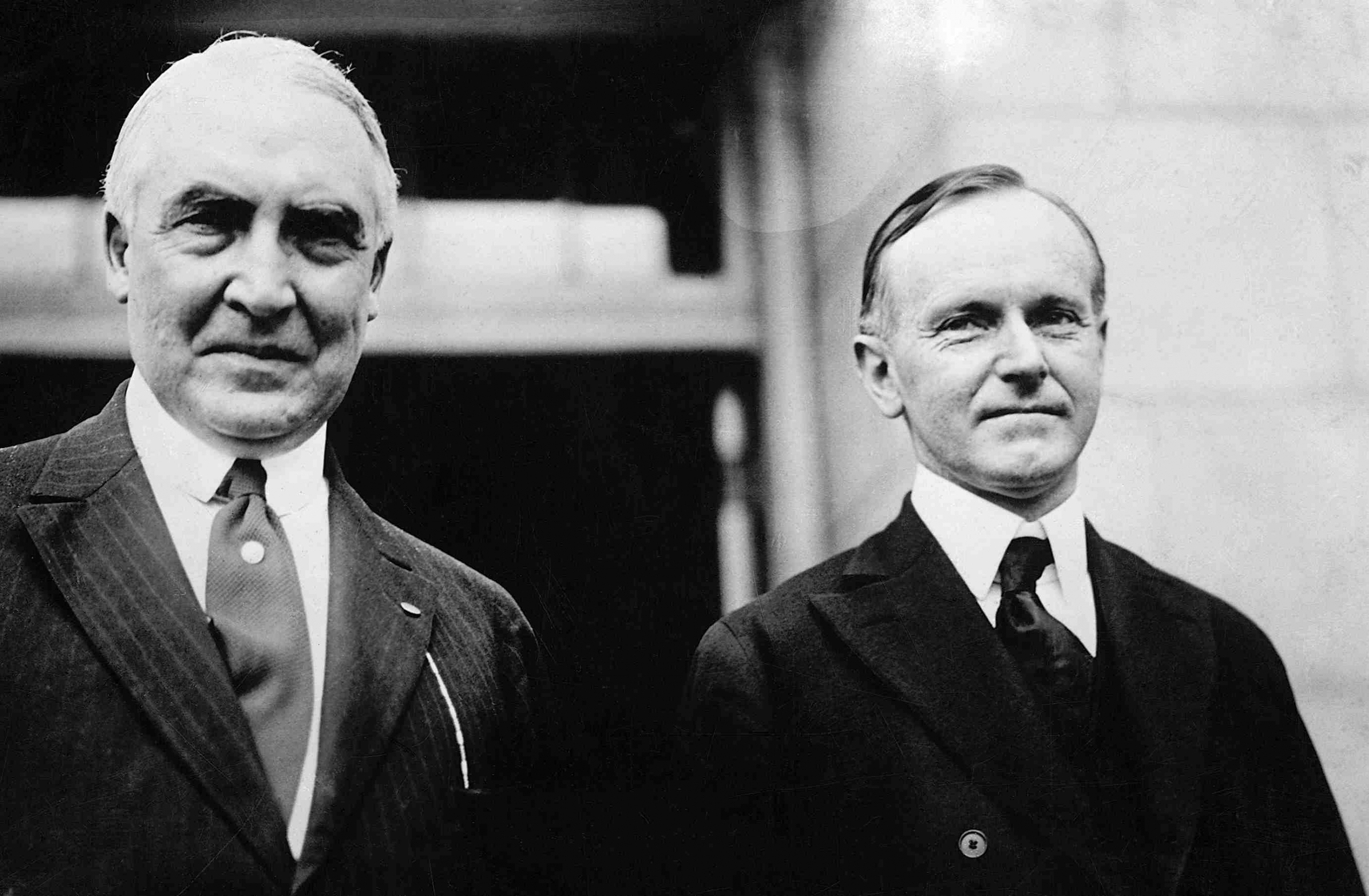

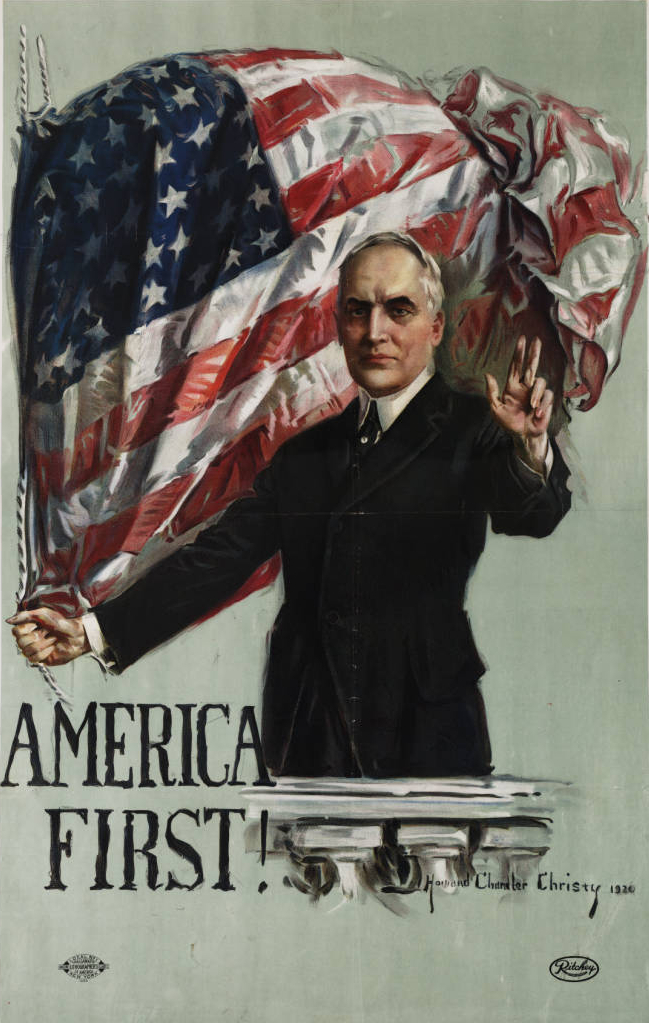

In response to war, globalism, pandemics, and an increasingly regulatory policy, the nation overwhelmingly elected Republicans Warren G. Harding and his Vice President Calvin Coolidge to the White House. The Harding/Coolidge ticket won by a margin of 277 electoral votes in addition to 26% of the popular vote. This clearly indicated a rejection of the progressivism championed by Woodrow Wilson and his party for so long.

In response to the recession Harding, “cut the government’s budget nearly in half between 1920 and 1922,” instituted tax cuts across the board, and saw the national debt, “reduced by one-third.”[33] When Harding died in office, Coolidge continued in that direction ensuring the booming economy of the 1920s.

A Different Outcome?

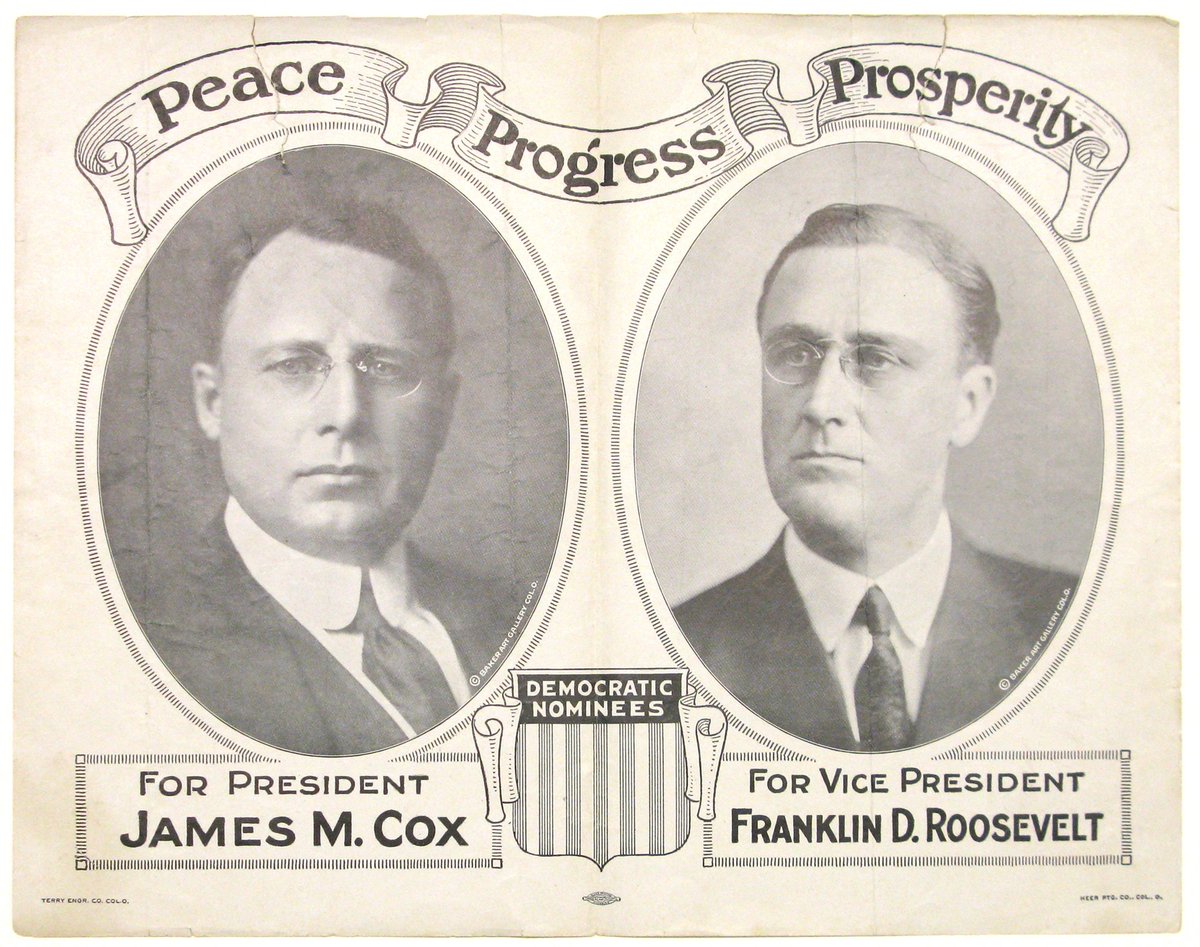

When the chains were removed from the nation the economy recovered to such a degree that the effects of the Spanish Flu were largely forgotten. But it could have been much different. In 1920 the democratic ticket consisted of James Cox for President and Franklin Delano Roosevelt for Vice President. Roosevelt’s predisposition towards widespread government involvement would become obvious during the 1930s and the New Deal legislation.

When the chains were removed from the nation the economy recovered to such a degree that the effects of the Spanish Flu were largely forgotten. But it could have been much different. In 1920 the democratic ticket consisted of James Cox for President and Franklin Delano Roosevelt for Vice President. Roosevelt’s predisposition towards widespread government involvement would become obvious during the 1930s and the New Deal legislation.

But James Cox’s views were not dissimilar to his more successful running mate. Even those in his own party recognized that Cox “thrives on campaigns” and offered no rebuttal to his acknowledged tendency of “being dictatorial.”[34] Indeed, even businessmen who supported Cox knew that his policies would be, “hostile to all our financial interests,” begrudgingly confessing that, “my financial interests must not and will not taint my political views.”[35] In short, Cox argued for the continuation of Wilson’s expansion of progressive government policies.[36]

Warren, on the other hand, ran on the platform of returning back to the basic foundations of Americanism. He explained that for all the government efforts and interventions:

Warren, on the other hand, ran on the platform of returning back to the basic foundations of Americanism. He explained that for all the government efforts and interventions:

“Normal thinking will help more. And normal living will have the effect of a magician’s want, paradoxical as the statement seems. The world does deeply need to get normal.…Certain fundamentals are unchangeable and everlasting.”[37]

Harding went on to observe that those who expanded the government during times of crisis, whether it be because of war or disease, are typically reluctant to return those powers back to the people:

“We have a right to assume the automatic resumption of the normal state, but power is seldom surrendered with the same willingness with which it is granted in the hour of emergency. But I think the conscience and conviction of the republic will demand the restored inheritances of the founding fathers.”[38]

In this Harding was soon proved to be correct. The American people did demand the return of their liberties and constitutional government. His election, followed by Coolidge’s leadership, steered America away from a growing government. However, such a direction did not last. The economic policies of Hoover allowed for the rise of Franklin Roosevelt who instituted the kind of sweeping action which Wilson and Cox only dreamed of.

Conclusion

As Americans today treads cautiously through a political landscape dominated by the threat of coronavirus, they would do well to remember the lessons of the Spanish Flu and the election of 1920. Similarly, in 1779, Thomas Jefferson, along with fellow signer of the Declaration George Wythe, explained that:

“Experience hath shown, that even under the best forms [of government] those entrusted with power have in time, and by slow operations, perverted it into tyranny; and it is believed the most effectual means of preventing this would be to illuminate, as far as practicable, the minds of the people at large, and more especially thereby of the experience of other ages and countries, they may be enabled to know ambition under all its shapes, and prompt to exert their natural powers to defeat its purposes.”[39]

The best way to defend America and the liberties we inherited is to learn from the past, and, “stand firm therefore, having girded their waist with the truth” (Ephesians 6:14). Otherwise, through measures sometimes imperceptible, conducted often during times of great duress, those freedoms which we ought to hold dear will be buried until a time when a new generation of patriots will rise up to retake them.

However, the American people on a whole have been vigilant throughout the centuries. If the election of 1920 is any indication, we have good reason to hope that this will continue. Let us all learn from the lessons of history, and fight the good fight, strongly finish the race, and keep always the faith.

Endnotes

[1] Kevin Daley, “California’s Stay-at-Home Order Raises Constitutional Questions,” The Washington Free Beacon (March 20, 2020), here.

[2] Gordan Chang, “Coronavirus Is Killing China’s Factories (And Creating Economic Chaos),” The National Interest (February 24, 2020), here; Keith Bradsher and Liz Alderman, “The World Needs Masks. China Makes Them, but Has Been Hoarding Them,” The New York Times (April 2, 2020), here.

[3] Jeffry Bartash, “Jobless Claims Soar 6.6. Million in Early April as Coronavirus Devastates U.S. Labor Market,” MarketWatch (April 9, 2020), here.

[4] U.S. Chamber Staff, “Quick Take: Coronavirus’ Economic Impact,” U.S. Chamber of Commerce (March 16, 2020), here.

[5] Eric Martin, “Coronavirus Economic Impact ‘Will be Severe,’ at Least as Bad as Great Recession, says IMF,” Fortune (March 23, 2020), here; “Coronavirus: Worst Economic Crisis Since 1930s Depression, IMF Says,” BBC News (April 9, 2020), here.

[6] “Coronavirus: Four Out of Five People’s Jobs Hit by Pandemic,” BBC News (April 7, 2020), here.

[7] Peter Ncholas, “There Are No Libertarians in an Epidemic,” The Atlantic (March 10, 2020), here.

[8] Nolan Smith, “Coronavirus Might Make Americans Miss Big Government,” Bloomberg Opinion (March 4, 2020), here.

[9] Michael Tanner, “Big Government Has Hurt Our Ability to Deal with This Crisis,” The National Review (March 18, 2020), here.

[10] Abdallah Fayyad, “The Pandemic Could Change How Americans View Government,” The Atlantic (March 19, 2020), here.

[11] Abraham Lincoln, Message of the President of the United States to the Two Houses of Congress at the Commencement of the Third Session of the Thirty-Seventh Congress (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1862), 23, here.

[12] “1918 Pandemic (H1N1 Virus),” Center for Disease Control and Prevention (March 20, 2019), here.

[13] Steven Burg. “Wisconsin and the Great Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 84, no. 1 (2000): 44.

[14] Burg. “Wisconsin and the Great Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 84, no. 1 (2000): 45.

[15] Steven Burg. “Wisconsin and the Great Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 84, no. 1 (2000): 46.

[16] Burg. “Wisconsin and the Great Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918.” The Wisconsin Magazine of History 84, no. 1 (2000): 48-49.

[17] Richard H. Peterson, “The Spanish Influenza Epidemic in San Diego, 1918-1919,” Southern California Quarterly 71, no. 1 (1989): 92.

[18] Peterson, “The Spanish Influenza Epidemic in San Diego, 1918-1919,” Southern California Quarterly 71, no. 1 (1989): 92.

[19] Peterson, “The Spanish Influenza Epidemic in San Diego, 1918-1919,” Southern California Quarterly 71, no. 1 (1989): 96.

[20] Richard H. Peterson, “The Spanish Influenza Epidemic in San Diego, 1918-1919,” Southern California Quarterly 71, no. 1 (1989): 96.

[21] Richard H. Peterson, “The Spanish Influenza Epidemic in San Diego, 1918-1919,” Southern California Quarterly 71, no. 1 (1989): 97.

[22] Ana Luisa Martinez-Catsam, “Desolate Streets: The Spanish Influenza in San Antonio,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 116, no. 3 (2013): 297.

[23] Martinez-Catsam, “Desolate Streets: The Spanish Influenza in San Antonio,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 116, no. 3 (2013): 297.

[24] “Las Vegas,” Albuquerque Morning Journal (October 20, 1919), 5, here.

[25] Nancy Rockafellar, “‘In Gauze We Trust’ Public Health and Spanish Influenza on the Home Front, Seattle, 1918-1919,” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 77, no. 3 (1986): 106.

[26] Rockafellar, “‘In Gauze We Trust’ Public Health and Spanish Influenza on the Home Front, Seattle, 1918-1919,” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 77, no. 3 (1986): 109.

[27] Rockafellar, “‘In Gauze We Trust’ Public Health and Spanish Influenza on the Home Front, Seattle, 1918-1919,” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 77, no. 3 (1986): 111.

[28] Thomas Garrett, Economic Effects of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Implications for a Modern-Day Pandemic (St. Louis: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2007), 19, here.

[29] Garrett, Economic Effects of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Implications for a Modern-Day Pandemic (St. Louis: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2007), 20, here.

[30] Garrett, Economic Effects of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic: Implications for a Modern-Day Pandemic (St. Louis: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 2007), 21, here.

[31] “Nisqually Valley,” The Washington Standard (November 8, 1918), 4, here.

[32] Calvin Coolidge, The Autobiography of Calvin Coolidge (New York: Cosmopolitan Book Corporation, 1929), 153, here.

[33] Thomas Woods Jr., “The Forgotten Depression of 1920,” Mises Institute (November 27, 2009), here.

[34] Charles Morris, The Progressive Democracy of James M. Cox (Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1920), 11, here.

[35] Roger Babson, Cox—The Man (New York: Brentano’s, 1920), 127, here.

[36] See, “1920 Democratic Party Platform,” The American Presidency Project (June 28, 1920), here.

[37] Warren Hardind, Rededicating America: Life ad Recent Speeches of Warren G. Harding (Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1920), 109, here.

[38] Warren Hardind, Rededicating America: Life ad Recent Speeches of Warren G. Harding (Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1920), 177, here.

[39] See, First Century of National Existence; The United States as There Were and Are (Hartford: L. Stebbins, 1875), 444, here

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!