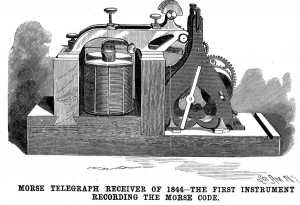

Samuel Finley Breese (F.B.) Morse (1791-1872) is best remembered for being the inventor of the American telegraph system and the Morse Code alphabet which is still widely used today. It was his development and perfection of an instantaneous method of electronic communication over long distances which contributed to the rapid expansion of the West during the late 1800’s and laid the groundwork for today’s 24/7 mass media culture.

Something which history widely forgets today about Morse’s great inventions, however, is the role God played throughout the process. Educated on religious matters from birth by his father, the notable Rev. Jedidiah Morse, Samuel developed a deep and sincere faith in God. In the two volume work, Samuel F.B. Morse: His Letters and Journals, his own son describes the inventor’s character:

The dominant note was an almost childlike religious faith; a triumphant trust in the goodness of God even when his hand was wielding the rod; a sincere belief in the literal truth of the Bible, which may seem strange to us of the twentieth century; a conviction that he was destined in some way to accomplish a great good for his fellow men.

Next to love of God came love of country. He was patriotic in the best sense of the word. While abroad he stoutly upheld the honor of his native land, and at home he threw himself with vigor into the political discussions of the day, fighting stoutly for what he considered the right….

A favorite Bible quotation of his was “Woe unto you when all men shall speak well of you.” He deeply deplored the necessity of making enemies, but he early in his career became convinced that no man could accomplish anything of value in this world without running counter either to the opinions of honest men, who were as sincere as he, or to the self-seeking of the dishonest and the unscrupulous.1

Morse’s pious character clearly exhibits itself in the historic message relayed during the public demonstration of the telegraph on May 24, 1844. Morse had promised Annie Ellsworth, the daughter of the Commissioner of Patents that she would get to decide what would be said. After talking with her mother, Annie decided to send a portion from Numbers 23:23: “What hath God wrought!”

Morse’s pious character clearly exhibits itself in the historic message relayed during the public demonstration of the telegraph on May 24, 1844. Morse had promised Annie Ellsworth, the daughter of the Commissioner of Patents that she would get to decide what would be said. After talking with her mother, Annie decided to send a portion from Numbers 23:23: “What hath God wrought!”

Early that morning, Morse and his guests gathered in the chamber of the Supreme Court while his assistant prepared to receive the fateful transmission in Baltimore. Then, at 8:45 a.m. on May 24, 1844, the electricity flowed through the line:

| . – – | . . . . | . – | – |

| W H A T |

| . . . . | . – | – | . . . . |

| H A T H |

| – – . | . . | – . . |

| G O D |

| . – – | . . . | . . | . . – | – – . | . . . . | – |

| W R O U G H T |

That message inaugurated the beginning of electronic media in America, setting off a chain of technological advancements which continues to this day nearly two-hundred years later. From the telegraph to the telephone to the internet, we all have good reason to declare, “What hath God wrought!”

Samuel Morse never forgot the role that God had in the development and success of the telegraph, always bearing in mind the powerful phrase selected by Annie Ellsworth. Later in life Morse explained that the telegraph was not merely an example of American ingenuity, but rather an example of God’s gracious providence:

Yet in tracing the birth and pedigree of the modern Telegraph, ‘American’ is not the highest term of the series that connects the past with the present; there is at least one higher term, the highest of all, which cannot and must not be ignored. If not a sparrow falls to the ground without a definite purpose in the plans of infinite wisdom, can the creation of an instrumentality so vitally affecting the interests of the whole human race have an origin less humble than the Father of every good and perfect gift?

I am sure I have the sympathy of such an assembly as is here gathered if, in all humility and in the sincerity of a grateful heart, I use the words of inspiration in ascribing honor and praise to Him whom first of all and most of all it is preeminently due. ‘Not unto us, not unto us, but to God be all the glory.’ Not what hath man, but ‘What hath God wrought?’2

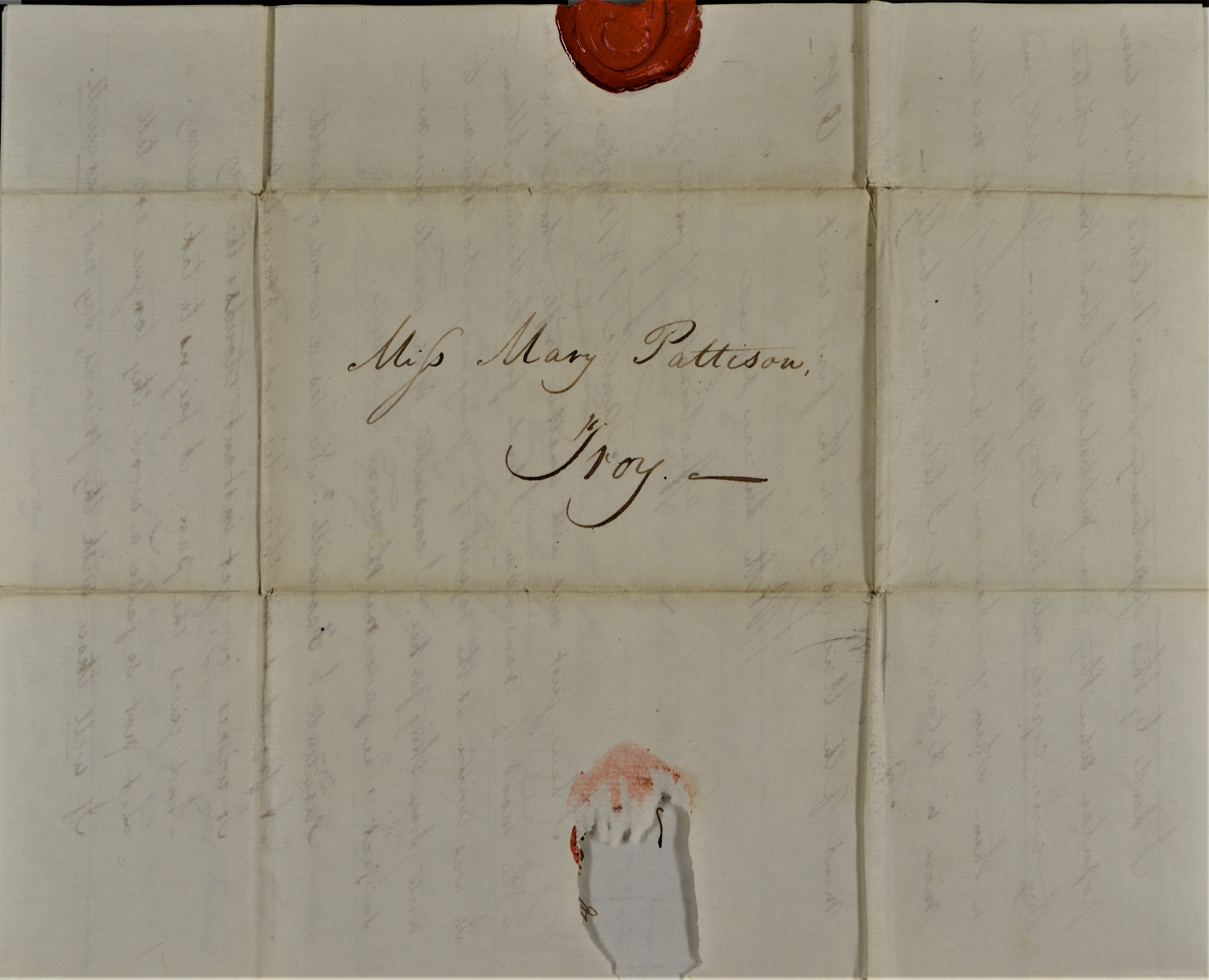

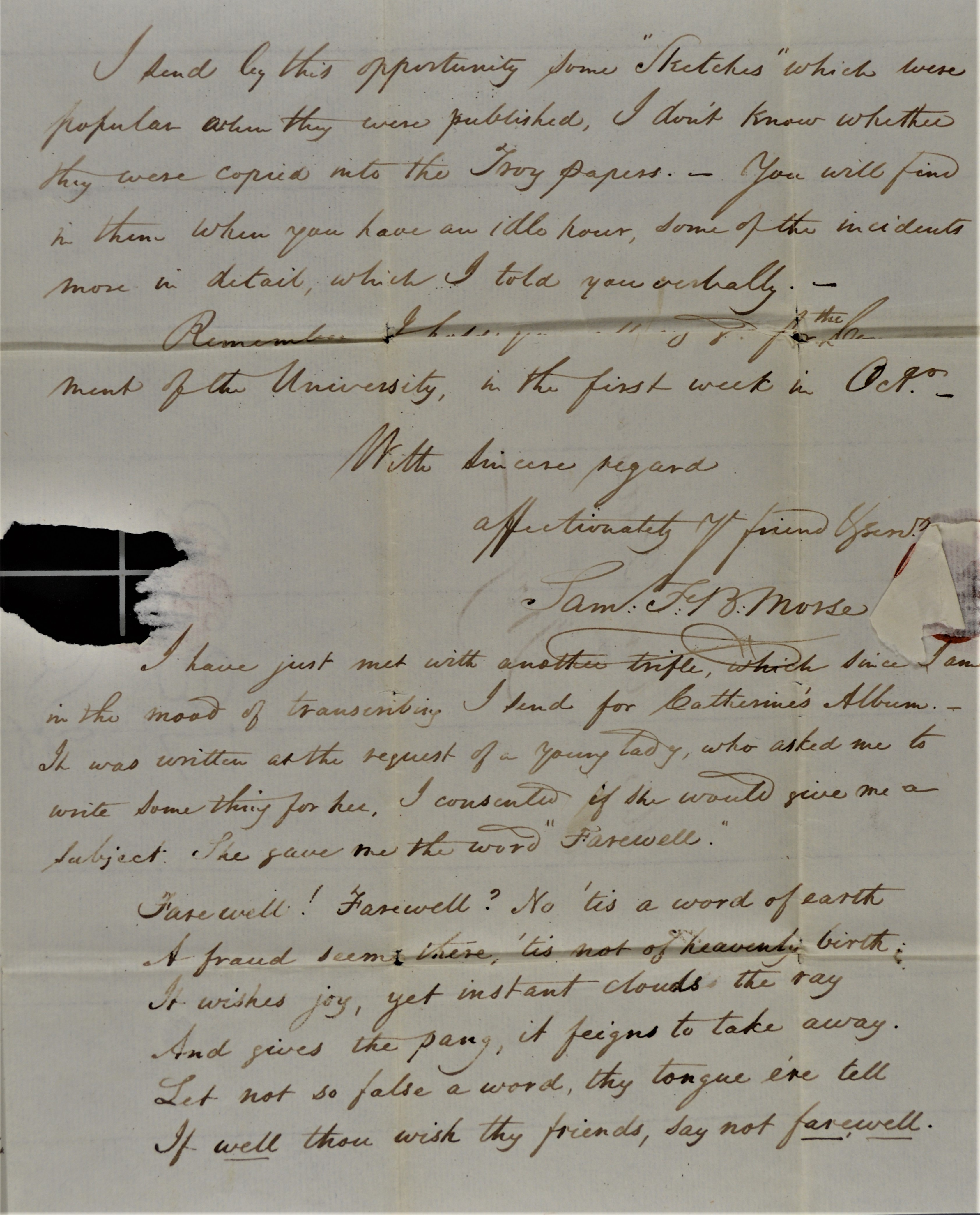

The WallBuilders’ Library is home to a handwritten letter from Samuel Morse composed in 1836, a full eight years before the triumph of the telegraph. In this personal letter to Miss Mary Pattison we get a glimpse into artistic side Morse’s mind through the portions of poetry he records, which also exhibit his deep devotion to God. Below is the transcript of the WallBuilders’ letter followed by pictures of the document itself.

Miss Mary Pattison, Troy

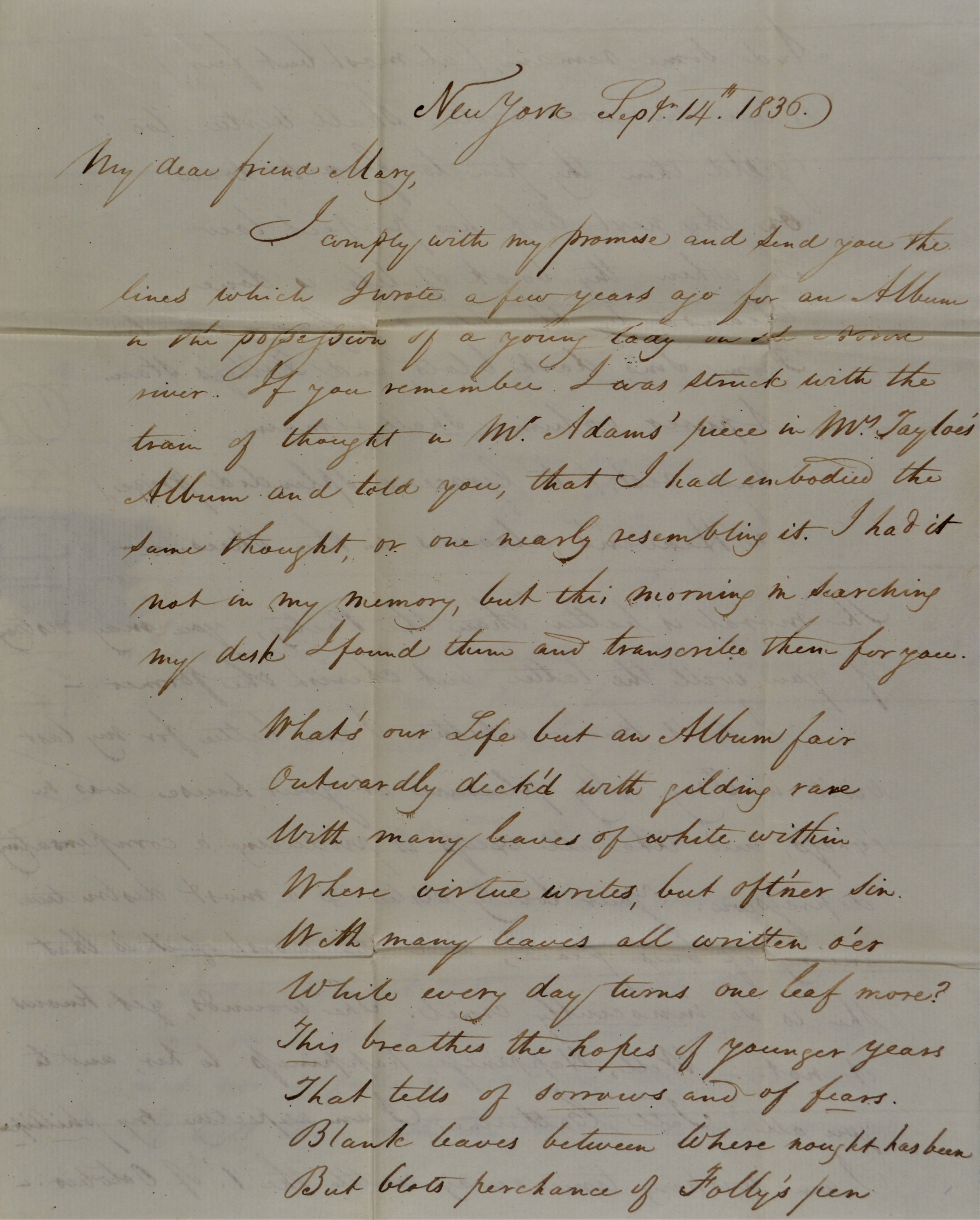

New York, Sept. 14th, 1836

My dear friend Mary,

I comply with my promise and send you the lines which I wrote a few years ago for an Album in the possession of a young lady on the North river. If you remember I was struck with the train of thought a Mr. Adams’ piece in Mr. Taylor’s Album, and told you, that I had embodied the same thought, or nearly resembling it. I had it not in my memory, but this morning in searching my desk I found them and transcribe them for you.

What’s our Life but an Album fair

Outwardly deck’d with gilding name

With many leaves of white within

Where virtue writes, but oft’mes sin

With many leaves all written o’er

While every day turns one leaf more?

This breathes the hopes of younger years

That tells of sorrows and of fears.

Black eaves between Where naught has been

But blots perchance of Folly’s pen

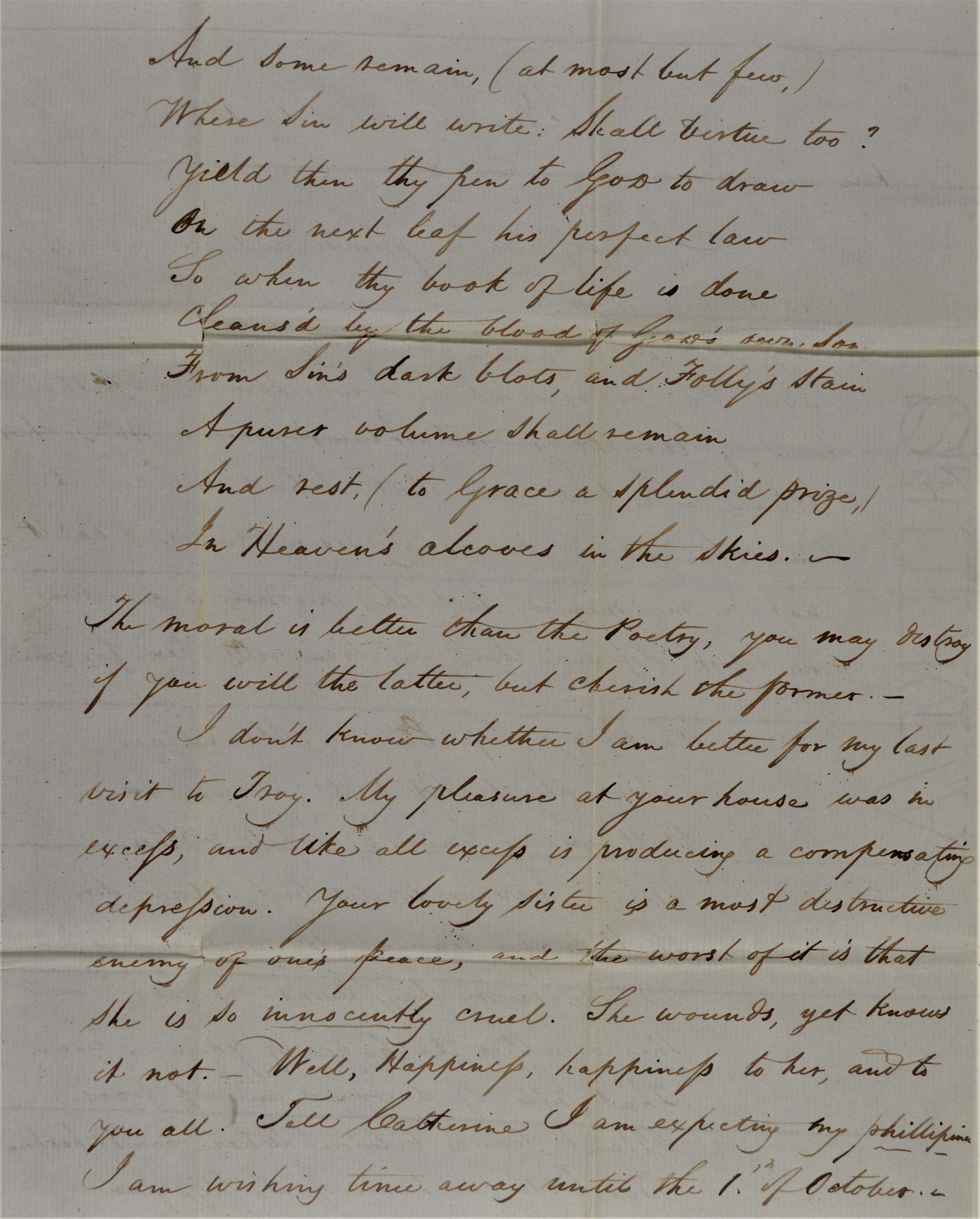

And some remain, (at most but few,)

Where Sin will write: Shall Virtue too?

Yield then thy pen to God to draw

On the next leaf his perfect law

To when thy book of life is done

Cleans’d by the blood of God’s own son

From Sin’s dark blots, and Folly’s stain

A purer volume shall remain

And rest, (to Grace a splendid prize,)

In Heaven’s alcoves in the skies.

The moral is better than the poetry, you may destroy if you will the latter, but cherish the former.

I don’t know whether I am better for my last visit to Troy. My pleasure of your house was in excess, and like all excess is producing a corresponding depression. Your lovely sister is a most destructive enemy of one’s peace, and the worst of it is that she is innocently cruel. She wounds, yet knows it not. Well, Happiness, happiness to her, and to you all. Tell Catharine I am expecting my Philippina. I am wishing time away until the 1st of October.

I send by this opportunity some “Sketches” which were popular when they were published, I don’t know whether they were copied into the Troy papers. You will find in them where you have an idle hour, some of the incidents more in detail, which I told you verbally.

Remember I hold you all engaged for the Commencement of the University, in the first week of October.

With sincere regard,

Affectionately your friend & servant

Sam. F.B. Morse

I have just met with another trifle, which since I am in the mood of transcribing I send for Catherine’s album. It was written at the request of a young lady, who asked me to write something for her. I consented if she would give me a subject. She gave me the word “Farewell.”

Farewell! Farewell? No ‘tis a word of earth

A fraud seen there, ‘tis not of heavenly birth.

It wishes joy, yet instant clouds the ray

And give the pang, it feigns to take away.

Let not so false a word, thy tongue ‘ere tell

If well then wish thy friends, say not farewell.

1 Edward Lind Morse, Samuel F.B. Morse: His Letters and Journals (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914), I:438-439.

2 Edward Lind Morse, Samuel F.B. Morse: His Letters and Journals (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1914), Vol. II, 472.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!