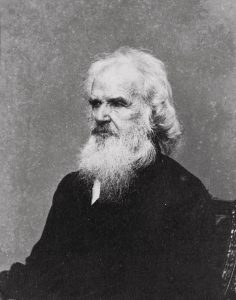

John Pierpont (1785-1866) Biography:

Born in Connecticut to a well-known family, he graduated from Yale in 1804. He worked as an educator for several years, then began studying law. In 1812, he passed the bar and went to work as a lawyer in Newbury, Massachusetts. But being dissatisfied as an attorney he became a merchant in Boston, then Baltimore, and next entered the study of theology. He graduated from Cambridge Divinity School and was ordained in 1819. He pastored a Boston church until 1845, then a church in Troy, New York, until 1849, and then another church in Massachusetts, where he pastored until 1856. While a pastor, Pierpont penned two of the more popular classroom school readers of that day. He was an abolitionist, a member of the temperance movement, a Liberty Party candidate for governor in the 1840s, and then a Free-Soil Party candidate for governor in 1850. He served as a Massachusetts field chaplain during the Civil War, but the physical demand was too great for his aging body, so he took an appointment in the Treasury Department in Washington, where he worked until his death in 1866. He was an accomplished poet and penned many published poems as well as sermons.

Born in Connecticut to a well-known family, he graduated from Yale in 1804. He worked as an educator for several years, then began studying law. In 1812, he passed the bar and went to work as a lawyer in Newbury, Massachusetts. But being dissatisfied as an attorney he became a merchant in Boston, then Baltimore, and next entered the study of theology. He graduated from Cambridge Divinity School and was ordained in 1819. He pastored a Boston church until 1845, then a church in Troy, New York, until 1849, and then another church in Massachusetts, where he pastored until 1856. While a pastor, Pierpont penned two of the more popular classroom school readers of that day. He was an abolitionist, a member of the temperance movement, a Liberty Party candidate for governor in the 1840s, and then a Free-Soil Party candidate for governor in 1850. He served as a Massachusetts field chaplain during the Civil War, but the physical demand was too great for his aging body, so he took an appointment in the Treasury Department in Washington, where he worked until his death in 1866. He was an accomplished poet and penned many published poems as well as sermons.

“Who Goeth A Warfare At His Own Charges?”

A DISCOURSE

Delivered Before the

ANCIENT AND HONORABLE

ARTILLERY COMPANY

OF MASSACHUCHETTS,

On the Celebration of Their 190th ANNIVERSARY,

BOSTON, JUNE 2, 1828

By JOHN PIERPONT.

Published at the Request of the Company.

BOSTON

Bowles and Dearborn, 72 Washington Street.

1828

Boston. Press of Isaac R. Butts & Co.

DISCOURSE

1 Corinthians, 9:17

Who goeth a warfare, at any time, at his own charges?

This question is proposed by the apostle Paul by way of illustration or argument. The point that he would prove is, that, as an apostle of Christ, giving up his time and powers for the benefit of those to whom he had been sent, and submitting to the labors and privations of the service in which he was engaged, he had a right to such compensation, from those for whom he labored, as would support him under his labors; or, as he himself states his point, he would prove that they who preached the gospel had a right to a living out of the gospel. This proposition he proves and illustrates by a variety of comparisons. The law of Moses permitted the priests, who were to superintend the offering of sacrifices in the temple, to feed upon the sacrifices they offered; and the ox, employed in treading or threshing corn, to eat of the grain that he threshed. And who, asks the apostle, feeds a flock, and does not eat of the fruit of the vineyard? Or who goeth a warfare at any time, at his own charges? Whoever thinks of serving as a soldier, of doing military duty, at his own expense; or, as the analogy of his argument requires, without being paid for his services by those for whose benefit they are rendered?

This last illustration of the apostle—this appeal of his to the common usage of nations, and to the common sense of mankind, as to what would be equitable,– might have been very pertinent in his day, to the point before him. Its force would have been felt, and his question must have been unanswerable. But in our days, should a soldier of the Cross, in an argument to prove that, as a minister of religion, he had a right to a support from those for whose benefit he labors, ask, “Who goeth a warfare at any time at his own charges?”—whoever does military duty at his own expense?—not one of his hearers but would answer, every militia-man in the country.

My friends and fellow citizens, I do not forget where I stand. I do not forget in whose presence, nor yet at whose bidding I speak. I stand in a Christian church—in one of the oldest of the churches of our fathers. I speak in the presence of the chief rulers and counsellors of the commonwealth, and at the bidding of an ancient and an honorable military company; a company the most ancient on the continent, and one in which some of the most honorable men of our country have been enrolled. I cast myself upon the honorable feelings which become men , whether they become soldiers or magistrates, with the full conviction that what I shall now say will not be misconstrued, as it certainly would be, were it construed into anything disrespectful to the memory or wisdom of our fathers, or to any individual of all those before whom I stand. Personal worth, as well as the feelings and opinions of all who are worthy, I cannot but hold in reverence. But while I do not forget where I am, I would not forget “whose I am, and whom I am bound to serve.” Knowing that, officially at least, I am a servant of the Lord, and being taught that “where the spirit of the Lord is there is liberty,” I know that, if that liberty is anywhere, it ought to be here, in his church; and believing that it is here, I claim it as my own, and as my own I will use it. I will use it; and will ask no protection of my gown from any responsibility for the manner in which I use it, if I speak of plain things in a plain way. Every citizen, so long as he is respectful to the legislator, has a right to examine his laws. If he sees that they are inequitable, if he feels that they are “needlessly oppressive to the community, and benefiting nobody on earth,” he has a right to say so. Nay, it is his duty to say so. It is his duty to lift up his voice against them; and, so far as he can, to make the pulpit and the press lift up their voices against them. It is his duty to examine them; if he deems them useless, to show their inutility; if absurd, to expose their absurdity. He will thus draw the public mind to them. They will become more and more, the subjects of free discussion. If there is good reason for them, good reasons will be given for them, and the wisdom of the laws will be made more widely manifest. If there are no such reasons, the public mind will , in time, become satisfied that there are none; and the public arm will, soon after that, disencumber itself of everything that burdens without strengthening it—will free itself of every thong, but that which carries as a sling, and that which binds on its shield.

Far be it from me, to say that there is no advantage gained, no blessing secured, by the militia system of our country, even as it is at present arranged and administered. The question that I would raise is this; Are the benefits that we secure by it, in any degree proportionate to the expense at which they are secured? Far be it from me to speak disparagingly of the wisdom of our fathers generally, or particularly of that wisdom which, in their day, they displayed, in the laws by which their military force was organized and governed—the laws by which they sought protection from danger which they felt. The question I would propose is, whether it is wise in us, under our circumstances, to do the same things, that it was wise in them to do under theirs. Far be it from me to question the bravery of American troops, even of militia-men. That has been doubted too often, and proved too often on those who have doubted it, for me to bring any skepticism in relation to it within the scope of the present discourse. I would rather ask, is there anything, in the present state of the country and the times, which requires our militia-men, at so great an expense to themselves, to show how valiant they would be if their valor were called for? Set an enemy of blood and bone upon our shore, and I think it would be very wise in us to let our militia-men charge bayonet upon him, and push him back into the water; and I verily believe, that the militia-men of Massachusetts would not be long in showing that they thought it very wise in them to do it. But is it as wise to keep them standing on the shore, with their bayonets bright and bristling, against such an enemy comes? Or marching and countermarching …

“——–In battailous aspect

Bristled with upright beams innumerable

Of rigid spears and helmets thronged,”

to guard against a foe that has already fallen—to overawe “The British ghosts that in battle were slain,” when, in other times, they came upon the shore?

True wisdom, I suppose, consists in adapting our conduct, and our laws, the rules of our conduct, whether as individuals or states, to the circumstances in which we are placed.

It is wise to foresee evil, and to guard against it. Prudence is a part of wisdom; prudence, which foresees danger. Courage is a part of wisdom; courage, which confronts the danger that it sees. But it is no more a part of wisdom to foresee danger and to confront it promptly, than it is to calculate the contingencies well, on which danger depend—to measure well the danger that may be apprehended, and to preserve a due relation between the probability of an uncertain evil, or the magnitude of a certain one, and the expense at which we would protect ourselves from an evil, certain or uncertain.

Does this position require illustration? It was wise, then, in Cairo or Constantinople to guard against the plague, at the expense of personal comfort and convenience. Would it be wise to demand the same sacrifices to guard against the same evil in St Petersburgh or Quebec? It is wise in the Hollanders, who have dyked out the German ocean from their plains, to look well to their dykes; to tax themselves freely for the support of their waterstaat; to keep a patrol moving, day and night, along those barriers, in raising and supporting which the Dutchman has purchased the right to take upon his lips, and that without impiety, the language of the Omnipotent, “Hitherto shalt thou come, and no farther, and here shall thy proud waves by stayed.” –But would the police which is wise on the east side of the German ocean, be as wise on the west?—and, if the guidman who tenants a ninth story on the rock of Edinburgh, should pay as readily and as roundly to insure himself against “the danger of the seas,” as does the respectable burgher of Amsterdam, should we think him eminently wise? In feudal times it was very wise in the English baron to make his house a castle. But if a New England farmer were, now, in order to protect himself against his neighbors, to make his house a castle, with its round-towers, and its donjon-keep, with its moat, and draw-bridge and port-cullis;–if he were to constitute his seneschal and wardours; and keep his…

“Nine and twenty yeomen tall,

Waiting duteous in his hall,

Ten of whom, all sheathed in steel,

With belted sword, and spur on heel,

Quitted not their harness bright,

Neither by day nor yet by night,

But lay down to rest with their corslet laced,

Pillowed on buckler cold and hard,

And carved at the meal with gloves of steel,

And drank the red wine through the helmet barred”—

His neighbors, I imagine, would begin to suspect that all was not right at “the castle,” and would take measures to place the knight upon a peace establishment in the asylum at Charlestown.

Perhaps I need not further illustrate my meaning when I say that true wisdom, whether we act as individuals or as states, consists in adapting our conduct, to the circumstances under which we are placed.

Now, with due deference to the opinions of the patriots of former days, by whom the militia laws were made, and with due deference to the opinions of the patriots of our own days, by whom those laws are not yet unmade, it does appear to me that, in the present constitution and operation of those laws, when considered in reference to the present circumstances of this Commonwealth and of our common country, there is not that wisdom discovered, which is shown in the general provisions and requirements of our civil polity.

But, as much as it is becoming the fashion of the day—and an excellent fashion it is—in adopting or rejecting opinions, whether in religion or politics, to ask. What are the reasons that support an opinion? Rather than who are the men that hold it?—I crave the ear of my audience, while I state a few of the reasons on which rests the opinion I have ventured to advance in respect to the militia laws of our country.

First, then, the militia system does not seem to me to discover the true wisdom of which I have spoken, because, under this system, we seek protection at an expense more than commensurate to our danger.

To satisfy ourselves whether this is so, we must compare the expense with the danger:–a comparison, it is admitted, which cannot be made with very great accuracy, though, I trust it may be well with all the accuracy that is necessary. What, then, is the annual expense of the militia of Massachusetts, to the state of Massachusetts?

The commonwealth has more than fifty thousand men, on her militia rolls. Grant that these are called out for review, drill, elections, and parade, no more than three days a year; and we have 150,000 days devoted to military duty by those who do that duty. Allow then only one spectator for one soldier—and it must be a very stupid affair if it there are not as many to see the show, as there are to make it,–and there are 150,000 days more. Allow moreover only two thirds as much time for each individual to prepare for the field—for fatigue or frolic—and to recover from its duties, or its debauch, as there is spent upon the field,–and we have 200,000 days more. Now, allowing that there is truth in the remark of a native citizen of Boston, who passes for a very sensible man, viz. that “Time is money,” and allowing one day to be worth only one dollar, the militia of Massachusetts costs the state of Massachusetts, half a million dollars a year. I make no accounts here, of the money spent upon arms, ammunition, uniforms—the ammunition that is burned up—the muskets and swords, and the costly coats of many colors are laid up—treasures that are kept, for the moth and rust to corrupt, three hundred and sixty days, that they may glisten and look gay for five:–I make no account of the monies, or the morals, that are thrown away in the low revelry of tents and taverns, though of these things there is a fearful account made by “ the Judge of all the earth:”—I estimate even the time of the militia-men at less than one third of the value which, in the form of fines for non-attendance, the law itself gives it, and the commonwealth of Massachusetts pays half a million of dollars a year for the protection which it seeks from its militia system.

Now, what is the danger against which protection is purchased at this rate? There are but two forms of danger against which a military force can protect the people of this commonwealth:–danger from insurrection, and danger from invasion. What is the danger to the citizens from insurrection? You have already answered this question, my hearers, in the view you entertained of the sanity that good farmer whom we just now supposed to have made his house a castle, fortified and guarded according to the usage of feudal times. And if there were danger from insurrection, the insurgents will have gained, from militia drilling, the same advantage in the use of arms against the loyalists, as the loyalists would have gained against them;–and it is worth our while to inquire what benefit, in a time of civil war, would result to the whole body politic, by having previously strengthened each of the hands of which both are using all the strength they have, in tearing the body to pieces. From the danger of insurrection, then, how are protected by your militia, granting that there were there danger from that quarter?

And what is our danger from invasion that we sacrifice so much of our substance to be protected from it?—what is the danger of Massachusetts? What if this Samson of the New England family rest,–ay, sleep even,–on the lap of Peace? Who are the Philistines that are going to be upon him before he can wake up and shake his locks at them? Are the Winnebagoes, and the Pawnees, and the Flat-heads, coming down to argue with us the title to the hunting grounds of the Pequods and the Narragansetts? And are we willing to compromise the suit and buy our peace at half a million dollars a year? Or do we make a good bargain when we pay that price, or any price, to secure our shores against invasion?

You do not need my friends, that I should answer these questions. I fear, rather, that you will say I am trifling with you when I ask them; and that they are below the dignity of my subject. But, before you say this, I beg you to consider that my present subject is the dangers that impend our civil state, dangers from which we seek protection under our militia system. If these dangers are trifles in themselves, we do not descend below the dignity of truth, in treating them as such. Truth does not always look black, and talk pontifically in her teachings. There is much truth, and as salutary truth, in the sunshine that plays upon the flower that it is showing you, or in the breeze that handles it lightly, while it gives you its odor, as there is in the voice or the visage of the thunder cloud that shows it. You pay seriously for that security from invasion, for which you look to the present operations of the militia system. If your danger from these quarters is such a trifle that it cannot be seriously named, my first objection to that system is a sound one, for you to look to it to protect you, at an expense that is beyond measure more than commensurate with your danger; and we have endeavored to show that to do this is not wise, for that “it is out of all proportion and relation of means to ends.”

My second objection to the present system is, that, granting a real danger, it affords a very inadequate security; and all the security that it does afford might be derived from it, were it so modified that it should be sustained at incomparably less expense.

That militia, trained or untrained, are competent to contend with regular and disciplined troops, during a whole campaign, no one pretends; or, if anyone believes that they are, let him inquire of any military man, and he will change his opinion. They are efficient only in a sudden emergency, or when acting in small parties, falling upon an enemy by surprise, or hanging upon his rear as sharp shooters, and taking off his numbers in detail. And this, I maintain, is a species of service for which the inhabitants of New England,–unless their right hand has strangely forgotten its cunning since the retreat of their enemy from Concord, and their own defeat at Bunker Hill—are as competent without the discipline of training days, and without red coats and plumes, as with them. I do but use the words of another, a distinguished advocate for the militia, a full believer in it, as well as an ornament of it, when I say, “The success which attended the mode of warfare by undisciplined troops at Lexington, was so marked that it is wonderful that it should since have been so much disregarded. The very men who , when formed in a body, scattered like sheep, upon the approach of the British columns, rendered signal services the same day, on the enemy’s retreat, when they were left to their intelligence.”[i]

Yes, to prove that militia cannot long be depended on, for defense against regular and veteran troops, the seat of our National government is a melancholy witness. And if, in proof of their efficiency in a sudden exigency, or in one brief struggle, I am pointed to Baltimore, or to New Orleans, or to Plattsburgh, or to Bunker Hill, or to the road “back again” from concord to Phipps’s farm, I answer—that just so efficient they would have been, indeed may we not say, thus dreadfully efficient they were, without the years of previous dressing, and drilling, and drumming—without the fifes and finery—without the pomp, and the pompons, and the parades which now cost the Commonwealth more than all she pays for the support of her municipal government, in its legislative, its judicial, and its executive departments:–ay, more than all that twice told.

I object, then, to the military system, in its present form and mode of operations, because in times of danger it affords inadequate security; as well as because in times when there is no danger it costs a very adequate price.

There is still another ground of skepticism as to the wisdom of the militia system, I its present form and operations. It is not equitable; and I need not labor to prove, that where there is no equity there is no wisdom. It is not equitable; for, while it purports to protect the whole, it throws the burden of all the protection that it does give upon a part of the community;–upon a small part;–upon a part not the most able to bear it, even, if it were righteous that they should bear it.

A late venerable chief magistrate of Massachusetts, when, in one of his general orders, he is magnifying the importance of the militia to the state, says—“the militia system was established for the protection of the property of the wealthy.” Then I say, let the wealthy pay for that protection. Do they pay for it? Look at the operation of the law. A wealthy justice of the peace, in the country, hires half a dozen young men to work upon his farm for six months, from the first of May to the last of October; the whole seasons for military operations. They are warned to do military duty, “for the protection of the property of the wealthy.” If they go, their wages, for the time employed in going, staying and returning, he diligently deducts in the day when he “reckoned with them.” If they do not go, he is the magistrate before whom you, as clerk of the company, bring your suits against them for their fines. You come into his presence with the delinquents.

“He wonders to what end you have assembled

Such troops of citizens to come to him,

His grace not being warned thereof before”–

but he pronounces upon them the sentence of the law, pays his own fine out of his own fees, deducts the “court day” from their calendar, and, if they cannot pay the amount of judgment, for fines, and fees, and costs of suit, the poor debtor’s prison will secure them, for six days, at least, from any further of their country’s claims upon their services in “protecting the property of the wealthy.”

“We should like to understand, if we may,” says a writer in one of the English Reviews, while commenting upon the orations of our Everett, and our Sprague, and our Webster—“We should like to understand, if we may, upon what principle the poor and the rich are taxed as they are, in the United States of North America, under the militia law. By the poor we mean those that are not rich, those who are neither wealthy nor destitute. Of both these are demanded about twelve days of their time to defend the property of the rich man. The rich, of course, do not appear in the field: the poor do. The latter cannot afford to keep away:–the former can. The poor lose, the rich gain, therefore, by submitting to the penalty. It is, moreover, notoriously true that, while the rich men never turn out, and the poor always do, the rich seldom or never pay the fine when they should pay it, and the poor seldom or never escape. The rich are let off; here, because they belong to this or that profession, either in church or state, or because they are doctors, or because they are teachers; there, because they are supported by the public, or have carried a commission two or three years in the militia: here, because they have contributed to the purchase of a fire engine; there, because they have encouraged a lottery: as if such people, were to have that property, whether of this or that profession,–teachers or not,–preachers or not,–officers or not,–having property, were to have that property defended by those who have no property—insured, we may say, at the charge of the latter.

“But why so unequal a tax, under a show of equality? If watchmen were needed for the guardianship of a city, where would be the wisdom, where the justice, of calling out every free male citizen of a particular age, for so many nights in the year—every one, rich or poor—under a penalty which would be very sure to keep the latter abroad in all weathers, while the former would be exempted, or excused, or suffered, in some way or other, to escape from the duty of watching their own houses? What if the poor man, who does go forth, were paid by the rich man who does not, for the guardianship of the public?—or at least for watching over the property of the rich man?”[ii] “Militias are but watchmen. The subject of their charge may be either a city or a state. Now the tax which is paid in the United States of North America for that guardianship is a poll tax. It should be a property tax. What if the militia were paid so much for every day’s labor?”

Thus asks the Reviewer: and I repeat the question—“What if the militia were paid for every day’s labor?”—I answer, in the first place, justice would then be done to the militia, which now is not: and, in the second place, I answer, that if they were paid, and if “a tax were laid equally upon every part of the community for the purpose of paying them,” I will consent to do militia duty again myself, if “every part of the community” were not stirring the inquiry, very soon, whether that enormous tax were necessary—whether the circumstances of the country and of the times were so fraught with danger, as to justify such sacrifices for security against that danger. The question would come up, whether anything more were called for, by a wise reference to the circumstances of the times, than, that arms should be provided at the public charge for the public defense,–that they should be deposited in places where they might be kept in order in time of security, and seized on in an hour in time of alarm: and if this were now thought to be enough, and if some measure like this were now adopted, for one, I doubt not that the good old commonwealth of Massachusetts, whenever she sees that “the Cambells are comin’” indeed, will soon muster a man to a musket,–a man, too, who, though he has never handled it on parade, will show his enemy that he knows what his musket was made for.

I have, thus far, endeavored to present to you, my hearers, some considerations, the object of which has been to bring your attention to the system of militia laws, in this commonwealth, especially so far as that system is subject to the legislative wisdom of the commonwealth,–apart from the provisions and requirements of the laws of the United States,–that, if it be found capable of amendment, it may, in due time, become the subject of amendment. I have endeavored to make myself understood. Would that I had power to make the evils of the system felt here, as they are felt by the citizen abroad.—If it be said that I manifest no respect for the law, my answer is, that I feel none. The framers of the system may have framed it wisely for their times; but since they have slept, and their graves have been hallowed, as they are hallowed, by the gratitude of their children, the times have changed; and if we are as wise as our fathers, our laws will be so changed as to be as well adapted to our times, as the laws of our fathers were to theirs. I would not be insensible to the value of those men’s services who have labored to accommodate the system to our times, nor yet deaf to the arguments which its advocates advance in its favor. Shall we consider one or two of these arguments?

We are told that the present trainings of the militia “teach civility and respect for authority.”—That the respect of the militia-man for the authority that subjects him to sacrifices and inconveniences, to fatigue and exposure and expense, which, with but half the sagacity and sensibility of an ordinary New Englander, he must see to be unnecessary, and feel to be oppressive,–will be proved, that his veneration for the laws will be put to a severe test, by these trainings—and that his civility, towards those officers who are required by their duty to exercise this authority, will be very adequately tried by these days of drill and review, indeed, I do not doubt. Bur that he will be taught respect for this authority;–or that he will learn any great civility, or show much of what he has already learned, while moving under the instant fear of being put under guard, I should think he must have a strong natural affinity to civility towards “men in office,” and a particular aptitude to learn respect for authority, to encourage us to hope.

We hear, too, of the benefit which the laboring part of the community derives from the relaxation and recreation furnished by the military holidays, and are told that the health and spirits are recruited by them.

In regard to these benefits, I shall not speak with confidence. It belongs rather to the medical generation to give an opinion in regard to them; and though every man, under our happy form of government, has a right to give his opinion as a statesman, not every man has a right to prescribe as a doctor. I have always understood, however, that alternation is one of the leading principles of discipline in the animal economy. The relaxation of the sedentary man is, therefore, to be sought in action, and that of the laborer in repose. What sanative power there may be to a laboring man, in the difference between working all day in one field-with a hoe, and working all day in another field with a gun, is a question which I shall leave with the faculty. I cannot but remark, however, that, admitting all the great benefit to the man who eats his bread in the sweat of his brow, that is claimed for him in an occasional relaxation from toil, and in a season of comparative repose, that benefit is secured to him by the gentle and most happy authority of our religion; which allows to him not five, but fifty days a year, in which he feels it a religious duty to rest from his labors, and enjoy the fruits of them in grateful adoration of the Divine Being.

But we are told, once more, that in discharging his military duties, a soldier, and especially an officer cultivates his sense of self-respect; he feels his importance to society, and acquires a habit of acting with a regard to his character. “Every man,” it is said, “who wears an epaulette, feels in a greater or lesser degree, the pride his station.”[iii]

Ay, “the pride of his station”—the pride of office. And are we certain that it is well that he should feel this pride of office, even as he does? Well for the community, or for the man himself who wears the epaulette?

Have you never seen the industrious young farmer, the respectable and thriving young mechanic, soon after he had put on his epaulette, pushed on by his pride out of sight of his prudence; stimulated by that badge of his country’s trust, to displays of hospitality, to the “gentlemen officers and fellow soldiers” of his corps, to which his means were not equal; taking counsel of his pride, rather than of his purse, for his own costume, and for the

“—–tilting furniture, emblazoned shields,

Impresses quaint, caparisons, and steeds,

Bases and tinsel trappings”

of his station; till his shop was forsaken, his farm mortgaged, his habits of industry broken up, and the man himself broken down? The zeal of the soldier hath eaten many a citizen up.

And if this pride of office will drive a man with one epaulette into a forgetfulness of himself, well may it be expected to drive a man with two, into a forgetfulness of others. Are you sure that your militia laws will always keep, within the limits which they have themselves marked out, those distinguished military characters, otherwise, most worthy and most valuable men, who have felt most sensibly this pride of office? If your laws allow as I suppose they do, a brigadier general, within certain limits, and on certain conditions, to call out his brigade for review in one body; is there no danger that a major general will mount an analogy of his own, and gallop to the conclusion that your laws allow him, which I suppose they do not, to call out his division for review in one body? And that your young men of civic habits and with constitutions conformed to civic habits, will be called out to fatigue duty, to sleep upon the tented field, and even on ground where no tents are, to wage a warfare, and that at their own charges, with cold and wet; a warfare at which a veteran might tremble, and in which Death seeks—ay, and ere yet has found, and followed till he seized, the soldier of a feebler frame! Have we not ground to suspect the pride of military office, and guard against its assumptions? Is there not a reason to believe, that where it conduces once to the public weal, it conduces twice to private wo?

But, it may be asked, shall we set at naught the parting counsel of the illustrious Father of his country, “that in peace we prepare for war. Let your navy guard your coasts at home, and plead for your interests and for your rights abroad—guard your coasts with fire, and plead with thunder for your rights. Let your armories ring with the “busy note of preparation.” Let your magazines of arms and ammunition be kept full, for the common safety, at the common charge. Let them stand, in their fullness, by your temples of justice, and, if need be, by every one of your temples of religion ; and doubt not, that when there is need, the worshippers in either temple will well know what those weapons mean. When, and where, did New England ever complain that, in her danger, she could not man all her guns? Or that she had more powder and shot on her hands, than her children were ready to take off? I have never read that chapter of her Lamentations. May we not argue to the future from the past? Dare we not trust our ships for protection from invasion—our ships of war, that, at the first foot-fall of a coming foe, would growl along our coast like watch-dogs? If we dare not, let us, like the prudent Belgians, listen to the suggestions of wisdom, and raise our barriers where our perils press. Let us listen to the teachings of our shores themselves, and what Nature has made strong, let us make stronger. Let our granite fortresses, that know look down in defiance upon the waves, be made to look down in defiance upon all that can float thereon. Let those surly and laconic pleaders, that argue the cause of nations in the last appeal—the “black but comely” brethren of your “Hancock’ and your “Adams” whose brighter, but not more honest faces are shining upon us today—be restrained, at the common expense, and seated, tier above tier, on our shore, their mouths filled with weighty arguments; and trust me, though the land behind them, in the meantime, be permitted to repose in security that has been graciously given it, whenever the trial comes on, those managers of your cause will show that a spirit of utterance has been given them.

Gentlemen of “The Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company”—in the freedom with which I have spoken of the present state and exactions of our militia laws—in questioning, as I have done, and as every citizen has a right to do, both their wisdom and their righteousness—I am sure that you will not understand me as treating with disrespect either the men who administer, or the men who obey those laws, it is but just to observe, that their altercations have almost uniformly been amendments, in that they have almost always consisted in softening their antecedent severity, and, in taking off something of the burden which they had before laid upon the shoulders of the citizen. In any age of improvement, it is not to be expected that public laws should be in advance of the public sentiment; but it is inevitable that, in a government of the people especially, they should not gradually follow the convictions and feelings of the community, in regard to the rights of the private citizen, and the degree of liberty, and of exemption from onerous duties, which he may justly claim, and securely enjoy. Your own records furnish evidence that the state of things, in this respect, is much better now than it was in the infancy of your company, when Upshal was doomed, by the voice of the law, to perpetual imprisonment, because, as a matter of the law, to perpetual imprisonment, because, as a matter of conscience, he refused to bear arms; and we ought to not doubt that, in time, the onward movement of the age will be so far felt by the laws, that they will no longer require the private citizen to go a warfare at his own charges, for the public benefit; or even to put on his panoply at all, against an ideal enemy, and, day after day, so to fight, “as one that beateth the air:” and till that time arrives, far be it from me, whatever I may think of the law, to speak disrespectfully of those who obey it. No; let every citizen who obeys the laws, be respected because he obeys them. If they are bad, let him change them, but not break them. Let him change them if he can, and let him lift up his voice, and put forth his power where he can, that they may be changed. We respect the citizen who obeys a law which he feels to be wise and righteous; but still more profoundly do we respect the citizen who obeys a law which he feels to be unrighteous and unwise, merely because it is the law. There is that which challenges not respect merely, but veneration in the sight of thousands of our fellow citizens quitting their homes, and, at their own inconvenience and cost, moving in martial array, toiling under the heats and burdens of a military day, and feeling, at the same time, that they are spending their strength for naught, and their money for that which is not bread, merely as an act of homage to the majesty of law.

No man in the community, however, is so insignificant that he may not do something for the benefit of the community. Your own company may do much, by the weight of your influence, and by the authority of your example, towards undoing the heavy burdens which may yet be borne by any part of society, without profit to the rest, and breaking every yoke under which the citizen is made to bend his neck, without either enriching or strengthening the state. By recurring to your past history, we see that yourselves have not unfrequently felt the pressure of pecuniary demands to be greater than you could conveniently bear; and though, by sumptuary laws, you have repeatedly striven against this pressure, and though some individuals of ample means have always been upon your roll, and though by great efforts , or by the excitement of particular occasions, your numbers have been swelled for a season; yet, again and again have they been “minished and brought low,” by the expenses incident to the objects and usages of your association.

It becomes you, to give a proper tone to the public feeling on this subject. Let me exhort you, therefore, having in all past time shown that, as soldiers, you cannot forget the state when she needs your services, to show now, that, as citizens, you will not forget yourselves, when she does not. Husband your resources; squander neither them nor your time in vain parade, or thankless hospitalities, in time of peace; and show that you are contributing to the glory and strength of the state, not by playing the soldier, but by acting the citizen: then: in times of danger and of war, if those times shall come, rally around the altar of your country, with the fruits of your of your peaceful labors. Cast your treasures upon that altar, with the promptness of the ancient and the honorable of other days; nay, if it must be so, leap upon that altar yourselves—a living and a willing sacrifice—and then, not on earth alone, but in heaven, will you be regarded as having offered a reasonable service.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!