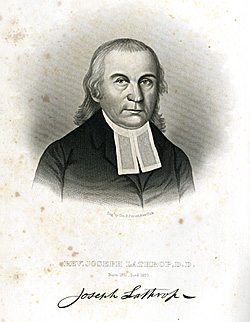

Joseph Lathrop  (1731-1820) Biography:

(1731-1820) Biography:

Lathrop was born in Norwich, Connecticut. After graduating from Yale, he took a teaching position at a grammar school in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he also began studying theology. Two years after leaving Yale, he was ordained as the pastor of the Congregational Church in West Springfield, Massachusetts. He remained there until his death in 1820, in the 65th year of his ministry. During his career, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity from both Yale and Harvard. He was even offered the Professorship of Divinity at Yale, but he declined the offer. Many of his sermons were published in a seven-volume set over the course of twenty-five years.

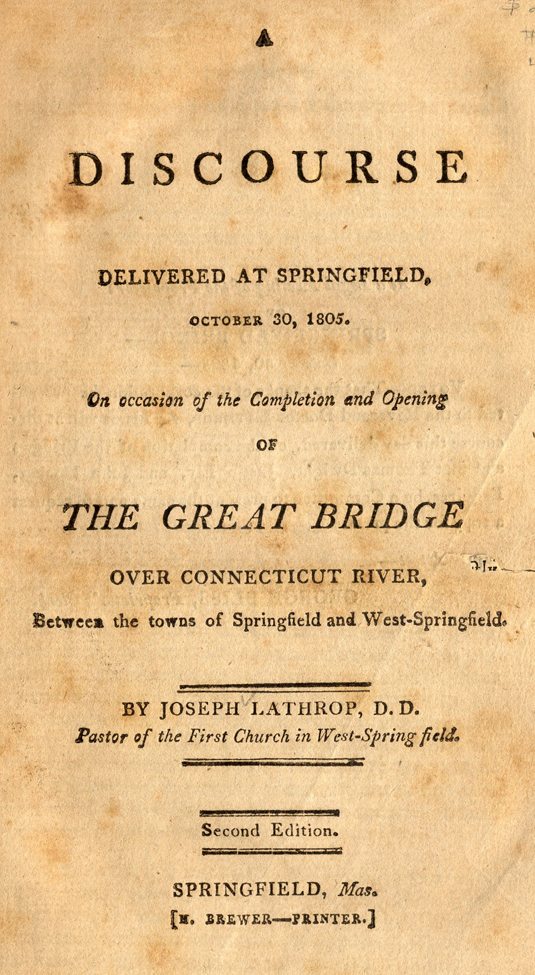

This sermon was preached on the opening of a bridge over the Connecticut River in Massachusetts.

DISCOURSE

DELIVERED AT SPRINGFIELD,

OCTOBER 30, 1805.

On occasion of the Completion and Opening

OF

THE GREAT BRIDGE

OVER CONNECTICUT RIVER,

Between the towns of Springfield and West-Springfield.

BY JOSEPH LATHROP, D.D.

Pastor of the First Church in West-Springfield.

At a Legal Meeting of the Proprietors

OF THE

SPRINGFIELD BRIDGE—

October 30, 1805—

Voted—That the thanks of the corporation be presented to the Reverend Doctor Lathrop, for his excellent discourse this day delivered, on the completion of the Bridge; and that Thomas Dwight, Justin Ely, and John Hooker, Esquires, be a Committee to present the same and to request a copy for the press.

Attest—

GEORGE BLISS, Proprietor’s Clerk.

Every rational being directs his operations to some end. To labor without an object, and act without an intention, is a degree of folly too great to be imputed to men. We must then conclude, that the Being, who created the world, had a purpose in view adequate to the grandeur of the work. What this purpose is the prophet clearly expresses in our text and a preceding verse. “He made the earth—he created man upon it—he formed it to be inhabited;” to be inhabited by men; by such beings as we are.

Let us survey the earth, and we shall find it perfectly adapted to this design.

Moses, in his history of the creation, informs us, that man was the last of God’s works. The earth was enlightened and warmed with the sun, covered with fruits and herbs, and stocked with every species of animals, before man was placed upon it. It was not a naked and dreary, but a beautiful and richly furnished world, on which he first opened his eyes. He was not sent to subdue a rugged and intractable wilderness, but to occupy a kind and delightful garden, where, with moderate labor, his wants might be supplied.

When Adam first awoke into existence, contemplated his own wonderful frame, surveyed the ground on which he trod, beheld the groves which waved around him, tasted the fruits which hung before him, and traced the streams which meandered by his side, at once he knew, that there must be an invisible Being, who formed this pleasant place for his habitation.

The same evidence have we, that the earth was made for the children of Adam.

The sun, that vast body of fire in the heavens, is so stationed, as to cheer and fructify the globe, and render it a fit mansion for human beings. By the regular changes of the seasons, those parts of the earth become habitable, which otherwise would be burnt with intolerable heat, or sealed up with eternal frost.

Around this globe is spread a body of air, so pure as to transmit the rays of light, and yet so strong as to sustain the flight of birds. This serves for the breach of life, the vehicle of sound, the suspension of waters, the conveyance of clouds, the promotion of vegetation, and various other uses necessary to the subsistence, or conducive to the comfort of the human kind.

The earth is replenished with innumerable tribes of animals, of which some assist man in his labors, some yield him food, and some furnish him with ornaments and clothing. “To man God has given dominion over the work of his hands: Under man’s power he has put all things; all sheep and oxen, the beasts of the field, the fowl of the air, the fish of the sea, and whatsoever passeth thro’ the paths of the deep.”

The productions of the earth are various beyond conception. Some spontaneous—some the effects of human culture—some designed for the support of the animal tribes, and some more immediately adapted to the use of man.

On the surface of the earth we meet with springs and streams at convenient distances to satisfy the thirsty beast, as well as to serve the purposes of the rational inhabitant. And beneath the surface there are, every where, continual currents of water, spreading, like the veins in a human body, in various ramifications, from which, with little labor, daily supplies may be drawn.

The great bodies of water, with which the land is intersected, furnish food for man, facilitate the commerce of nations, and refresh and fertilize the earth.

By the heat of the sun, and other co-operating causes, waters from the seas, rivers and fountains are raised into the cooler regions of the atmosphere, there condensed into clouds, wafted around by winds, and sifted down in kind and gentle showers. Thus, are our fields watered without our labor or skill.

The earth supplies us with timber, stone, cement, metals, and all necessary materials, from which we may fabricate implements for labor, coverts from cold and storms, Bridges for passing the streams, and vessels for navigating the seas.

The natural world is governed by uniform and steady laws. Hence we may judge, within our sphere, what means are necessary to certain ends, and what success may ordinarily attend the works of our hands.

Now to what end was all this order and beauty of nature—this fertility and furniture of the earth, if there were none to contemplate and enjoy them? Without such an inhabitant as man to behold the works, and receive the bounties of God, this earth would be made in vain; it might as well have been a sandy desert, or an impenetrable rock.

But still the earth, richly furnished as it is, would lose more than half of its beauty and utility, if man the possessor were not endued with a faculty of invention and action. “This also cometh forth from the Lord of hosts, who is wonderful in counsel and excellent in working—for his God doth instruct him to discretion, and doth teach him.” God has done much for man; but has left something for man to do for himself. The materials are furnished to his hand; he must sit and apply them to actual use.

In the first stages of the world, when its inhabitants were few, its spontaneous productions in a great measure supplied human wants. But as men increased in numbers, they found it necessary to form society, institute government and introduce arts for a more easy, and less precarious subsistence, and for more effectual defense and security. History carries us back to the time when arts first began—when iron and brass were first wrought into utensils by the hand of the artificer—when tents and houses were constructed for human accommodation—when musical instruments were invented to amuse the mind, or to assist devotion. The history which we have of the beginning and progress of arts—the state in which we now see them, and the improvements made in them within the time of our own recollection, all tend to confirm the Mosaic account of the origin of the world.

The improvement in arts, tho’ in general but slow, has nearly kept pace with human exigencies. For some time past, their progress has been remarkable. Their present state of advancement would have been thought incredible a century ago. A century hence there may be such additional discoveries and improvements as would seem incredible now.

Not only in Europe, but also in our own country, especially since our late revolution, great progress has been made in astronomical discoveries, by which navigation is assisted;—in medical science by which diseases are prevented or cured—in agriculture by which our lands have much increased in their produce and value—in instruments and machines to expedite and diminish human labor—in the mechanical construction of mills and other water-works to effect the same and superior ends by a lighter impulse of water—in the formation and erection of Bridges to break the power of ices, and withstand the impetuosity of floods—in opening artificial canals by which the falls and rapids of streams are surmounted or avoided, and in “cutting our rivers among the rocks, and binding the floods,” so that an inland navigation is accomplished.

Who among us, twenty years ago, expected to see the two banks of Connecticut river united at Springfield by a Bridge, which should promise durability? Yet such a structure we see, this day, completed and opened for passage—a structure which displays the wealth and enterprise of the Proprietors, and the skill and fidelity of the artificers, and which will yield great convenience and advantage to the contiguous and neighboring towns and to the public at large.

“Except the Lord build the edifice, they labor in vain that build it; and except the Lord keep it, the watchmen wake in vain.” In a work of this kind, there is the same reason to acknowledge the favoring and preserving hand of God, as in all other enterprises and undertakings; and more in proportion to its complexity, difficulty and magnitude. The seasons have kindly smiled on the operations; and the work was nearly completed without any unhappy accident or evil occurrent.

We lament the casualty, by which a number of the workmen were endangered, some were wounded, and one lost his life, A NAME=”R1″>1 a life important to his family and valuable to society. And yet, considering the nature of the work, the length of time spent, and the number of people employed in it, we must gratefully ascribe it to the watchful care of providence, that no other casualty has occurred. And when we consider the suddenness and unforeseen cause of that event, by which so great a number were imminently exposed, we see great cause of thankfulness, that it was not more disastrous. They who escaped without injury, or with but temporary wounds, ought often to look back to the time, when there was but a step between them and death.

This work, tho’ the unhappy occasion of one death, may probably be the means of preserving many lives. If we were to calculate on the same number of men, employed for the same number of days, in constructing and erecting our ordinary buildings, we should certainly expect casualties more numerous and disastrous, than what have happened in this great, unusual, and apparently more dangerous undertaking.

The structure which we this day behold, naturally suggests to us a most convincing evidence of the existence and government of a Diety.

Let a stranger come and look on yonder Bridge; and he will at once know that some workmen have been there. Let him walk over it, and find that it reaches from shore to shore; and he will know that it was built with design, and will not feel a moment’s doubt what that design is. Let him then descend and examine the workmanship; and he will be sure, that much skill and the nicest art have been employed in it. And now let this same man cast his eyes around on the world, observe its numerous parts, the harmonious adaptation of one part to another, and of all to the use and benefit of man; and he will have equal evidence, that there is a God, who made, sustains and rules this stupendous fabric of nature, which he beholds every day, and which surrounds him wherever he goes.

Such a structure as yonder Bridge convinces us of the importance of Civil Society, and of a Firm and Stead Government.

It is only in a state of society and under the influence of government, that grand works of public utility can be effected. There must be the concurrence of many—there must be union and subordination—there must be transferable property—there must be a knowledge of arts—there must be some power of coercion; none of which can take place in a savage state. An agreement purely voluntary among a number of individuals, without any bond of union, but each one’s mutable will, would no more have been competent to the completion of this Bridge at Springfield, than it was anciently to the finishing of the tower on the plains of Shinar. It was necessary here, that there should be a corporation vested with a power of compulsion over each of its members, and with a right to receive gradual remuneration, for the expense of the work, from those who should enjoy the benefit of it. And such a corporation must derive its power and right, as well as existence, from superior authority.

The man of reason will pity the weakness, or rather despise the folly of those visionary and whimsical philosophers, who decry the social union, and the controlling power of government, and plead for the savage, as preferable to the civilized state of mankind, pretending that human nature, left to its own inclinations and energies, “tends to perfectability.”

If society were dissolved and government abolished, what would be the consequence? All the useful arts would be laid aside, lost and forgotten; no works of public utility could be accomplished, or would be attempted; no commercial intercourse could be maintained; no property could be secured, and little would be acquired; none of the conveniences and refinements of life could be obtained; none of the cordialities of friendship and relation would be felt; more than nine tenths of the human race must perish to make room for the few who should have the good fortune, or rather the misfortune, to survive.

Compare now the savage and the civilized state, and say; Is it better, when you are on a journey, to climb ragged mountains, and descend frightful precipices, than to travel in a plain and level road? Is it better to pass a dangerous stream by swimming with your arms, or by floating on a log, than to walk securely on a commodious bridge? Is it better to till your ground with your naked hands, or with a sharp stone, than with the labor of the patient ox, and with instruments fabricated by the carpenter and the smith? Is it better to cover your bodies with hairy skins torn from the bones of wild beasts, than with the smooth and soft labors of the loom? Is it better to starve thro’ a dreary winter in a miserable hut, than to enjoy a full table in a warm and convenient mansion? Is it better to live in continual dread of the ruthless and vengeful assassin, than to dwell in safety under the protection of the law and government?

When men plead for the preference of the savage to the social state, they either must talk without thought; or must wish to abolish a free government, that it may be succeeded by another more absolute, in the management of which they expect a pre-eminent share.

The work, which we this day see accomplished, suggests some useful thoughts, in relation to the nature of civil society.

The undertakers of this work have steadily kept their great object in view, have pursued it with unanimity and zeal, have employed artificers skillful in their profession, and workmen faithful to their engagements, and they have spared no necessary cost. Thus, they have seen the work completed to their satisfaction and to universal approbation.

Here is an example for a larger society. Let every member act with a regard to the common interest, and study the things which make for peace. In his single capacity, let him be quiet and do his own business; but when he acts in his social relation, let the general interest predominate. Let him detest that false and miserable economy, which, under pretext of saving, enhances expense, and ultimately ruins the contemplated object. Let him never consent to withhold from faithful servants their merited compensation. In the selection of men to manage the public concerns, let him always prefer the wise to the ignorant, the experienced to the rude, the virtuous and faithful to the selfish and unprincipled, the men of activity in business, to the sauntering sons of idleness and pleasure; and in such men let him place just confidence, and to their measures yield cheerful support. Thus he may hope to see the works of society conducted as prudently, and terminated as successfully, as the work which we this day admire.

In the work itself we see an emblem of good society. The parts fitly framed and closely compacted together, afford mutual support, and contribute, each in its place, to the common strength; and the whole structure rests firm and steady on a solid foundation. In society there must be a power of cohesion, resulting from benevolence and mutual confidence; and there must be a ground work sufficient to support it, and this must be Religion.

It is obvious, that no society can subsist long in a state of freedom, without justice, peaceableness, sobriety, industry and order among the members; or without fidelity, impartiality and public spirit in the rulers. It is equally obvious, that the basis of these virtues can be nothing less than religion. Take away the belief of a divine moral government, and the apprehension of a future state of retribution; and what principle of social or private virtue will you find?

It is too much the humor of the present day to consider religion as having no connection with civil government. This sentiment, first advanced by infidels, has been too implicitly adopted by some of better hearts….But it is a sentiment contrary to common experience, and common sense, and pregnant of fatal evils. As well may you build a castle in the air, without a foundation on the earth, as maintain a free government without virtue, or support virtue without the principles of religion. Will you make the experiment? Go, first, and tear away the pillars from yonder Bridge. See if the well-turned arches will sustain themselves aloft by their own proportion and symmetry. This you may as well expect, as that our happy state of society, and our free constitution of government will stand secure, when religion is struck away from under them.

If a breach should happen in those pillars, immediate reparation will doubtless be made. Let the same attention be paid to the state of religion and morals. Let every species of vice and every licentious sentiment be discountenanced—be treated with abhorrence—Let virtue and piety be encouraged and cherished—Let the means of religion be honored and supported. Thus only can our social happiness be maintained; thus only can we hope, it will descend to our posterity.

The progress of arts naturally reminds us of the importance of revelation.

The acquisition of these is left to human experience and invention. Hence they are more perfect in the present, than they were in preceding ages. But to instruct us in moral duties and in our relations to the invisible world, God has given us a Revelation, and this he has communicated to us by men inspired with his own spirit, and by his son send down from Heaven. Some arts, known in one age, have been lost in succeeding ages. If we attentively read the book of Job, we shall find, that in his day, the arts, among the Arabians, had risen to a degree of perfection, of which some following ages could not boast. But the revelation, which God has given us, he has taken effectual care to preserve, so far that no part of it is lost to the world.

Now say, Why has God given a revelation to instruct us in the truths and duties of religion, and none to instruct us in the husbandry, astronomy, mathematics and mechanics? May we not hence conclude, that religion is a matter which demands our principal attention?

If a number of men should combine to exterminate the arts, who would not deem them enemies to mankind? Who would no rise to oppose so nefarious a design?—But these would be harmless men compared with the malignant enemies of revelation. Yet the latter may talk and write; and hundreds may attend to, and smile at their talk, and may read and circulate their writings; and few seem concerned for the consequences. Yea, some will scoffingly say, “If religion is from God, let him take care to preserve it;” as if they thought, none were bound to practice it, and none but God had any interest in it.

While we contemplate the progress of arts, we are led to believe a future state existence.

If this world was made for man, certainly man was not made merely for this world, but for a more exalted sphere. We have capacities which nothing earthly can fill—desires which nothing temporary can satisfy. This rational mind can contemplate the earth and the heavens—can look back to its earliest existence and forward to distant ages—can invent new arts—can improve on the inventions of others, and on its own experience—can devise and accomplish works, which would have been incredible to preceding ages—can make progress in science far beyond what the present short term of existence will allow. Its wishes hopes and prospects are boundless and eternal. There is certainly another state, in which it may expand to its full dimensions, rise to its just perfection, and reach the summit of its hopes and prospects…o, my soul, what is wealth or honor, a mass of earth or a gilded title to such a being as thou art, who canst contemplate the glorious Creator, partake of his divine nature and rejoice forever in his favor? The inhabitants of the earth, like travelers on the bridge, appear, pass away and are gone from our sight. They enter on the stage, make a few turns, speak a few words, step off, and are heard and seen no more! Their places are filled by others, as transient as they. How vast is the number of mortals, who in one age only, make their appearance and disappearance on this globe? Can we imagine, that these millions of moral and rational beings, who, from age to age, tread the earth, and then are called away, crop into eternal oblivion? As well may we suppose, that the successive travelers on that Bridge terminate their existence there. This surely is a probationary state. Here we are to prepare for a glorious immortality. For such a design the world is well adapted. Here God makes known his character and will, dispenses a thousand blessings, mingles some necessary afflictions with them, calls us to various services, puts our love and obedience to some trials, gives opportunity for the exercise of humility, gratitude, benevolence, meekness and contentment, and proves us for a time, that in the end he may do us good.

This world has every appearance of a probationary state—that it really is such, revelation fully assures us. Happy is our privilege in the enjoyment of a revelation, which instructs us, what beings we are, for what end e were created, what is our duty here, and what is the state before us.

God manifests himself to us in the frame of our bodies, in the faculties of our minds, in the wonders of his creation, in the wisdom of his providence, in the supply of our wants, and the success of our labors; but more fully in the communications of his word. Into our world he has sent his own Son, who, having assumed our nature, dwelt among mortals, taught them, by his doctrines and example, how they ought to walk and to please God, opened to them the plan of divine mercy, purchased for them a glorious immortality, and prepared a new and living way into mansions of eternal bliss.

Let us gratefully acknowledge and assiduously improve our moral and religious advantages; regard this life, as it is, a short term of trial for endless felicity and fullness of joy; and while we remain pilgrims here on earth, walk as expectants of the heavenly world.

Let us be fellow helpers to the kingdom of God. That is a kingdom of perfect benevolence. To prepare for that state, we must begin the exercise of benevolence in this. God is the great pattern of goodness. Our glory is to be like him. We then shew ourselves to be like him, to be his children and heirs of an inheritance in his kingdom, when we love our enemies, relieve the miserable, encourage virtue and righteousness, and promote the common happiness within the humble sphere of our activity and influence.

How active and enterprising are many in the present day, to facilitate an intercourse between different parts of the country by preparing smooth roads in rough places, by stretching Bridges over dangerous streams, and by opening canals around rapid falls, and through inland towns?—Their motives, we trust, are honorable; but whatever be their motives, they are advancing the interest and prosperity of their country. May all these works be a prelude to works more pious and more extensively beneficent. May the time soon come, when an equal zeal shall appear to remove all impediments, which lie in the way of a general spread of the gospel and a general conversion of mankind to the Christian faith. May the public spirit, which operates so successfully in the former cause, rise and expand until it ardently embraces the latter. May we soon hear a voice, crying in the wilderness, “Prepare ye the way of the Lord, make strait in the desert a high way for our God. Cast ye up, cast ye up, prepare the way, take up the stumbling blocks out of the way of his people.” And may we see thousands and thousands promptly obeying the call. “Then shall every valley be filled, and every mountain and hill shall be brought low; the crooked shall be made strait, and the rough ways shall be made smooth. And all flesh shall see the salvation of God.”

Endnotes

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!