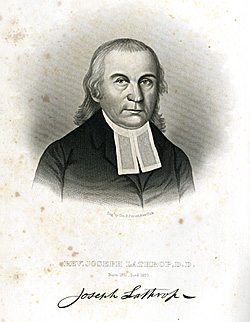

Joseph Lathrop  (1731-1820) Biography:

(1731-1820) Biography:

Lathrop was born in Norwich, Connecticut. After graduating from Yale, he took a teaching position at a grammar school in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he also began studying theology. Two years after leaving Yale, he was ordained as the pastor of the Congregational Church in West Springfield, Massachusetts. He remained there until his death in 1820, in the 65th year of his ministry. During his career, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity from both Yale and Harvard. He was even offered the Professorship of Divinity at Yale, but he declined the offer. Many of his sermons were published in a seven-volume set over the course of twenty-five years.

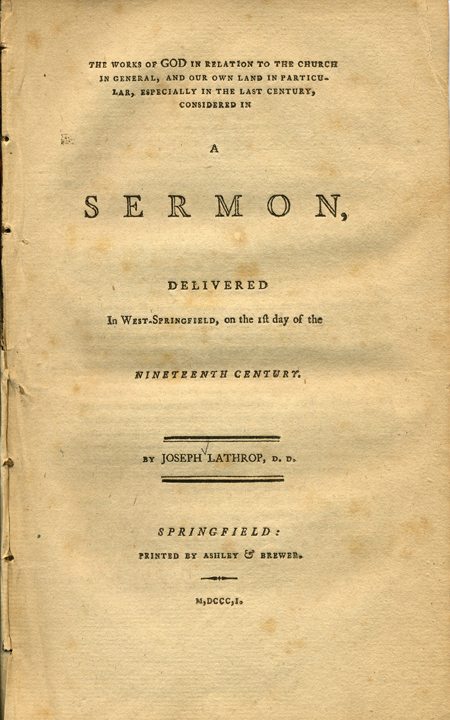

Lathorp delivered this message on January 1, 1800, ushering in the new era.

Dr. Lathrop’s

CENTURY SERMON.

The works of GOD in relation to the church in general, and our own land in particular especially in the last century, considered in

A

SERMON,

Delivered

In West-Springfield, on the 1st day of the

NINETEENTH CENTURY.

By JOSEPH LATHROP, D. D.

PSALM LXIV. 9

All men shall fear, and shall declare the work of God for they shall wisely consider of his doing.

As God manifests himself to us in his works, it is our wisdom to contemplate them, as far as they come within our view. And we are to consider them wisely; in their connection with one another, and their relation to their end; in the benefits resulting from them to ourselves and to mankind. To consider them piously and devoutly, that our conceptions of the Author may be enlarged, our gratitude to him enlivened, and our faith in him established.

The contemplation of God’s works may be daily exercise, but there are particular seasons which especially invite us to this agreeable employment. The anniversary of great events and the beginning of a new year may, with great propriety, be chosen for this devout purpose. The emancipation of the Jews from Egypt gave them a new epoch, and fixed the month in which their ecclesiastical year should in future begin. This event was ever after to be recognized by a festival celebrated in the same month.

Civilized nations have generally had an era from which they dated their time. The Greeks dated their time. The Greeks dated from the institution of their public games; the Romans from the building of their city; the Turks and Arabians date from the flight of their prophet from Mecca to Medina. Christian nations have a more remarkable epoch, the birth of that wonderful person, who taught their religion, founded their Church, and purchased their salvation. This epoch came not into immediate use among Christians It was first used by Dionysius a Roman abbot, in the beginning of the sixth century; and next by Bede, and English writer, in the beginning of the eights century. After him it soon came into general use. The French that they might wipe away the very remembrance of Christianity, have with the Sabbath, abolished this era, and substituted their own revolution. Other nations retain it, and all Christian nations will doubtless continue to retain it in memory of the great Redeemer.

As this day begins, not only a new year, but a new Century from that memorable era, it is proper that we should employ a part of it in recollecting the works of God, and wisely considering his doings. And as we date our time from the birth of the Savior of men, and the Ruler of the Church, God’s doings in relation to the Church in general, o our own country in particular, and more especially in the last century, will most naturally fall under our contemplation.

In surveying so spacious a field, we can only select some of the most prominent objects.

The though which first meets us is grand and solemn. Eighteen hundred years ago was born in Judea the great Redeemer of our fallen race. After spending about thirty years in private life, he appeared on the public theatre, taught that divinely excellent religion which is conveyed to us, and confirmed the truth of it by his miraculous works, then voluntarily submitted to a death on the cross for the expiation of human guilt and for the father proof of his heavenly mission; soon returned from the dead, and, after spending a few days among his disciples, visibly ascended into heaven in the presence of more than five hundred people. Before his ascent, he founded a Church, or rather enlarged the foundation of the ancient Church, and commissioned a number of his disciples, whom he had educated for the work, to go forth into all the world, and by their preaching and miracles to collect subjects into his kingdom. And he left them a promise, that he would never forsake the faithful ministers of his word, and that his Church founded on the truth, as on a rock, should stand unmoved, and the gates of hell should never prevail against it. His promise we, to this day, see remarkably verified, and hence receive fresh evidence of the truth of his religion.

The religion of Jesus soon made a mighty progress. It subverted the idolatry and polytheism of the heathens, reclaimed them from their abominable vices, introduced among them a traditional worship, and formed them to virtuous manners. Within the age of the Apostles it had spread over the greatest part of the Roman Empire, and found a place even in Cesar’s household. That a religion so holy, so contrary to the opinions and vices, the habits and prejudices of the world, should, in so short a time, so far extend its power, in the hands of such weak instruments, is an undeniable evidence, that a divine energy accompanied it, and that its origin was from Heaven.

In its progress, however, it met with great opposition: but this opposition operated to display its dignity and increase its influence.

Among the Jews arose the first persecutors of the Christian Church. Of the believing Jews many fled into other parts to escape the persecuting rage of their countrymen. The dispersed Christians carried their religion with them, and by their means it became more extensively known.

The Jews, at this time, had only a limited government of their own: their country was a province of the Roman Empire. In about forty years after the crucifixion, they were totally subdued and extirpated by the Romans, whom they had exasperated by repeated insurrections, being excited thereto by a false expectation of a Messiah to deliver them from this foreign government, and to give them dominion over all nations.

Their rejection of the gospel of Christ was the direct cause of their destruction. Had they believed in the Savior already come, they would not have looked for another, nor in this vain expectation have risen in arms against the Romans. In this war, in which they resisted their enemies with an enthusiastic ardor, they were finally conquered, multitudes perished, the rest were captivated and dispersed. The have never since existed in a national form, and never will, till the fullness of the Gentiles shall come in. They fell by their infidelity, we stand by faith. Let us not be high minded, but fear. If a people, who have had the gospel, explode it for the abominable licentiousness of infidelity, misery, and destruction await them.

The first Christian Church was in Judea. It might naturally have been expected, that the conquest of that country would have been the extinction of the Church. But it proved the reverse this conquest was an awful display of God’s wrath against the enemies of truth, and a striking accomplishment of the prophecies delivered by Christ, a few years before, concerning this grand catastrophe. The dissolution of the Jewish state suppressed the most implacable enemies of the Church. The dispersion of the Jews spread the knowledge of the Old Testament, and the flight of Christians disseminated the doctrines of the New, and both concurred to awaken enquiry and excite attention. The present state of the Jews, wholly expatriated, everywhere dispersed, generally despised, often oppressed, and still preserved a distinct people, is so singular, so correspondent to prophecy, and so expressive of God’s design to collect them again into a national capacity, that it must be regarded as a standing proof of the divinity of the gospel.

Christianity, in the second and third centuries, while it was in progress in the empire, suffered repeated persecutions from the pagan powers. But still it increased and grew. Persecution kept the zeal of Christians alive, and directed it to its proper object, their exemplary piety, peaceableness and benevolence confounded the accusations of their enemies; and the power of divine grace remarkably animated them in their dangers, and supported them in their sufferings. Hence many were constrained to confess, that God was among them of a truth.

In the beginning of the fourth century, the Church had a season of rest. Constantine the Great was called to the imperial throne. He, being a friend to Christianity, put an end to her grievous persecutions. In him was in some measure fulfilled the prophet’s prediction concerning the Church that “kings should be her nursing fathers.” This prediction will be more eminently fulfilled in a happy age yet to come. After the government of the empire fell into the hands of Christian princes, the Church enjoyed a season of prosperity. Her increase and happiness in this period, John, in the 7th chapter of the Revelations, describes by the sealing of 144,000 out of the tribes of Israel, and by the accession of innumerable multitudes from all nations of the earth. The happy alteration in the state of the Church consequent on the transition of the government from Heathen to Christian Princes was a new subject of praise in Heaven. On this occasion the saints and the angels fell down before the throne of God, ascribing to him blessing and glory and thanksgiving for the salvation which he had granted to the Church. If any imagine that civil government in a Christian land may safely be committed to infidels, let them recollect that this is not the opinion of Heaven. Saint Paul, indeed, directs Christians to be subject to, and peaceable under the then existing government, though administered by heathen magistrates : but where Christians have the power of choice, he instructs them to submit their temporal controversies to wise men chosen from among themselves; not to unbelievers, or heathens, who were least esteemed in the Church.

In this state of security, the Church, after some time, degenerated into a lukewarm and worldly spirit. Heresies of various kinds started up, as is common, when the power of religion declines; and Christians, now delivered from their common enemy, fell into warm altercations and violent animosities among themselves. In this period, Arianism, or the denial of the proper divinity of Jesus Christ, first disturbed the peace of the Church. Before this time, Christians had spoken of the Trinity in the God head, and the character of Christ, very much in the language of scripture, and thus had avoided all dangerous controversy on these mysterious subjects. But, Arius a presbyter of Alexandria, hearing, in the assembly of Elders, the divinity of Christ asserted in terms, which he thought exceptionable, rose in opposition to it, and affirmed, that Christ, though the noblest of creatures, still was but a creature. His opinion was warmly embraced by many, and by many as warmly opposed. The Church was divided; the parties hereticated each other, and by their intemperate zeal produced distraction and violence. Other controversies grew out of this; an immoderate heat attended them; and pure and practical religion was in danger of being consumed in the flame of party zeal. Christians now needed, and soon they experienced new judgments to arrest their attention to, and engage their hearts in the practical concerns of religion.

In the fifth century the northern barbarians in prodigious numbers broke into the western empire, and carried conquest and devastation with them. They plundered and demolished opulent cities, laid waste large tracts of country and took and sacked Rome itself, overturned the ancient government and established their own, and divided the empire into those ten kingdoms, which Daniel and John had foretold under the figure of ten toes on the feet of Nebuchadnezzar’s image, and ten horns on the head of the beast. From the fulfillment of these prophecies there arose a new proof of the divinity of the scriptures. These calamities, for a while threatened the destruction of the empire and the extinction of the Church; but they ultimately proved favorable to mankind, and to the Christian cause. They repressed the exorbitant power of the empire, checked the growing luxury of the age, and called the attention of serious Christians to the solid doctrines and precepts of religion; and they eventually contributed to the spread of the gospel; for these victorious barbarians, instead of imposing their own superstitions, adopted the religion of the countries which they conquered. They, however, mingled with Christianity some of their pagan ceremonies, and thus unhappily prepared the way for a more easy introduction of the papal superstition. But the corruption, now openly appearing, awakened, for the present, the concern of pious Christians, and roused the zeal of the abler and better part of the clergy, to explain the nature, assert the simplicity and vindicate the truth of the religion taught in the gospel. Thus pure religion was maintained amidst gross and threatening corruptions.

When Christianity began to assume a worldly form, avarice and ambition became motives to spiritual offices and ecclesiastical distinctions. The successive pastors of the church in the city of Rome felt and discovered the influence of these motives in a peculiar manner. They contended for a superiority in office above other ministers, and for the preeminence of this Church above other Churches. And in the beginning of the seventh century, the Bishop then in office succeeded I his ambitious project so far as to obtain from the Emperor the title and authority of Pope, or Supreme Head of the Church. In the middle of the next century the Roman pontiff was vested with civil authority. This papal power is supposed to be the beast in the Revelation. This is to continue from the time of its rise, 1260 years. If we date its rise from the former of these periods, it is within about 60 years of its fall; if from the latter, it will stand 200 years longer. Its present condition does not promise so long a duration.

After the papal power began to operate, ignorance and superstition more and more prevailed, and the Church sunk into dismal bondage and darkness. The pontiff claimed a superiority over kings, assumed the power of remitting and indulging sins, pretended to infallible knowledge, took the scriptures out of the hands of the people, and disposed of their property and their souls according to his own sovereign will. The spirit of liberty and enquiry was almost suppressed, and pure, genuine Christianity scarcely to be found.

In this dark period, however, there were some, who had better discernment, maintained the truth, and lamented the general corruption. These were the two witnesses, who, during the reign of the beast, were to prophecy, clothed in sackcloth. Some efforts for a reformation, from time to time, were made; but with little success, until the beginning of t the 16th century when God remarkably appeared for the support of the sinking Church and the revival of expiring Christianity. Men of eminent ability and invincible fortitude were raised up, who opposed the vices and corruptions of the times with a force of argument which confounded their adversaries, and with boldness of spirit, which astonished the world. Their preaching awakened the drowsy multitude to enquiry, and their writings, aided by the art of Printing, now lately invented, gave the pure doctrines of the gospel a rapid spread. The Pope, feeling his danger, had recourse to arms: many princes, embracing the reformation role in its defense. A war commenced which, continuing for some years with various success, terminated in favor of the reformed religion.

The reformation soon made a public appearance in England, the country of our fathers, where the principles of it had been more privately taught for many years. It met, however, with violent opposition, and suffered severe persecution. In one reign it was conceived and protected, in another it was condemned and execrated by the ruling powers, until about the middle of the sixteenth century, when, in the reign of Elizabeth, it was fully established. Attempts to subvert it were afterward made, but they were providentially defeated.

The reformation, though a glorious, was an imperfect work. Many pious and discerning people wished it might be carried to greater purity: but if this might not be done, they at least, wished for themselves to be excused from a compliance with certain ceremonies retained in the English Church; and on this condition, they would gladly have continued in her bosom. But in this request they could not be indulged. An unqualified conformity to all her established ceremonies was an indispensable term of communion. They were therefore compelled to withdraw. These puritans, as they were now called, suffered great oppressions and cruelties from the bigotry of the Church and the tyranny of the court. They were deprived of the rights of humanity as well as of conscience. They were dragooned from the sanctuaries of worship, hunted in their secret retreats, ferretted from place to place, until wearied out with dangers, and worn down with sufferings, they sought asylum, firs in Holland, and then in the deserts of America.

We are now, in the course of our narrative, come to our own country. Had persecution and tyranny been unknown in Europe, America might long have remained a wilderness. How important are the consequences of those oppressions, which our fathers suffered! What a mighty territory is here cultivated, once a wilderness, the haunt of savage beasts and men more savage! How much has Europe been populated by emigrations to, and enriched by commerce with the American world! She supports millions more than could have been nourished in her bosom, if she had derived no assistance from America. What an increase of human liberty – what a spread of knowledge – what a growth of wealth – what an enlargement of the Church, have followed from events which portended nothing but misery! How unsearchable are the ways of God!

The settlement of New England, which began in the year 1620, was at a time, and in a manner the most favorable that can be imagined, to the introduction of the Gospel in its genuine purity. It was a little after the reformation from Popery, and just before the eruption of infidelity in England. The reformation was there established about sixty years before, and the first deistical book was there published by Lord Herbert about ten years, and the next by Hobbes, about thirty or forty years after the settlement of this country began. Had it begun a little earlier, Popery would have been the prevailing religion: had it been deferred a little longer, the seeds of infidelity, planted with it, would have taken root in the soil, and produced their poisonous fruits with the luxuriance, in which they have appeared in some parts of Europe. The period of the settlement seems to have been providentially chosen for the purpose of preserving the purity of religion. The principal adventurers in this arduous enterprise were men distinguished for their ability and learning their zeal and fortitude. Hence Churches were immediately erected, eminent ministers settled, decent provision made for their support, and a college soon founded and endowed to supply the Churches with learned ministers. Our fathers had too much wisdom to think that illiterate men were capable of performing the ministerial duties; they had too much honesty to pretend that divine inspiration would supersede a learned education; they furnished themselves for the service of the Churches, should perform the service at their own charges.

The settlement of New England was begun by a small number of people. There arrived at Plymouth in 1620 no more than 101 persons; and of these nearly half died in the ensuing winter. In the space of twenty years, there came over from England about 21,000 persons, men, women and children, of whom few settled in Plymouth were the soil was uninviting, but the greater part planted in Massachusetts, Hampshire, Maine, and other places. After the year 1640, there were few emigrations from England, as persecution had then ceased; and many, who had come hither, returned to enjoy the sweets of their native land.

The perils and distresses of these settlers in a dreary wilderness, filled with savages, must have been inconceivable, and their preservation and increase remarkably providential; as it was at any time in the power of savages to have extirpated them, had they not been mercifully restrained. There were times, however, when the natives, apprehensive of danger from these increasing foreigners, attempted a general combination for their destruction. The most distinguishable seasons of danger, were in the conspiracy of 1630, in the Pequot war of 1636, and in Philip’s war of 1675, in which Springfield was burnt, and many other towns; some within 20 miles of Boston. But these combinations were broken and defeated; and the two last with such destruction and terror to the natives as greatly facilitated the progress of the English settlements. These wars, however, were exceedingly calamitous. By a computation made at the close of Philip’s war, the losses sustained by the English amounted to £150,000 besides expenses incurred in their defense. There were 1,200 houses burnt: 8,000 head of cattle of all kinds killed; several thousands of bushels of grain destroyed; and great numbers of the active men and promising youth of the country slain. Of the Indians, it is said, more than 3,000 were destroyed.

About the year 1664, the colonies were alarmed with a danger of a different kind. Their enemies here and in England had been secretly plotting to annihilate or abridge their charter privileges. Commissioners were now sent from the king, vested with powers incompatible with these privileges; and they opened and exercised their powers with a hauteur which indicated no friendly design. By the prudent firmness of the colonial assemblies, especially that of Massachusetts, the commissioners were disappointed and with some disgust embarked for England. Apprehensions still remained, that by their unfavorable report to the king, new displeasure would be raised, and a new attempt made against the colonies. But the commissioners, in their homeward voyage, by storms and capture, lost all their papers, and no report was ever made.

In 1686 the design was renewed with more serious effect. James II a bigoted papist and an arbitrary tyrant being seated on the throne, resolved, as his brother Charles had done before him to establish through his dominions the popish religion and an absolute government. But he proceeded with less cautious steps, than Charles had done. He seized the charters of corporations in England, and demanded the New England charters. These infant colonies, unable to contend with the king, yielded to the imperious mandate. The Connecticut charter was saved by an artifice, and afterward resumed; but for the present it efficacy was lost with the rest. Sir Edmund Andros was appointed governor-general, and vested with absolute powers to rule the colonies. He arrived at Boston in December 1686, and soon began the exercise of his authority. From this time, for about two years, all civil and religious liberty was suspended, and seemed to be lost. Printing presses were restrained; congregational ministers were treated as laymen, and personally insulted; attempts were made to invalidate their marriages; meeting houses were threatened with demolition, and congregational worship with interdiction. The fees of officers were fixed by themselves at an exorbitant rate. The business of probate was conducted by the governor; and widows and orphans from the remote parts of the country were obliged to repair to Boston, and pay an immoderate fee for the probate of a will. Few estates in that early period would bear the expense of a settlement in the probate office. Titles to lands were declared void without a patent from the governor, the cost of which, in many instances was more than the owners could pay; nor was the current money in the country adequate to the purchase of new titles for all the possessors. In this matter the Governor found it necessary to relax. The people were taxed at the pleasure of the Governor and four or five of his Council, without an assembly of their own. No town meeting could be held without special license. In short, ever vestige of former liberty was obliterated. Provoked by intolerable oppression and encouraged by intelligence of a probable revolution in England, the people took the desperate resolution to seize and imprison the Governor and his creatures, and to resume their charter-government. This was a bold and adventurous act: But the abdication of James and the accession of William in 1688, delivered the people from servitude and danger, and restored them to liberty and security. In four years after this, our charter was granted by William and Mary. By this the colonies of Plymouth and Massachusetts were united. This, though less popular than the charter, which was lost, yet placed the people in a tolerable situation, and soon gave general satisfaction. If Britain had not been too exorbitant in her claims, it is probable we should for some time have been happy and contented under it. We have come to the century which is just closed. Here we meet events no less interesting. To trace their connection would be entertaining; but time will permit us only just to detail, them. This country in its dependence on Britain was involved in all her wars, which have occupied one half of the past century. These wars, though calamitous in themselves, have usually terminated favorably for us; and, together with the frequent incursion of the natives, they have obliged us to keep op that military spirit, which displayed itself so successfully in our late conflict with Britain.

The capture of Louisbourg, in 1745, by the New England forces, assisted by a few British ships, was a wonderful event. It raised the respectability of the colonies, gave them an idea of their strength and importance and enabled the British government to conclude a tolerable peace, after an unsuccessful war in Europe, and while it excited in that government a jealousy of our future attempts for independence, and suggested the expedience of bringing us more absolutely under their control, it strengthened our resolution to defend our liberties.

The defeat of the formidable French fleet, which, in the following year, was sent to recapture Louisbourg and destroy our coasts, and which had escaped the vigilance of the British fleet, was a striking instance of the care of providence for this favored country; for this defeat was effected wholly by the hand of Heaven – by unusual storms, sickness and mortality, without any human means.

The war, which began in 1755, and closed in 1763, was still more important in its consequences. It not only delivered us from the incursions of the savages, by which for 130 years we had been frequently alarmed and distressed; but drove the French from their encroachments on the claims of the British government, and put into the hands of that government a territory extending from the Atlantic to the Mississippi. In consequence of this acquisition, we now possess a territory vastly larger than could have been ceded to us in our treaty of peace with Britain, if the French had retained their encroachments. That war prepared the way for us to become a great and might nation. It operated to our independence in another respect. The prodigious expenses of that war put the British ministry on devising new expedients to increase their revenue. Among these the taxation of America was one. Their unbounded claims alarmed the spirit of freedom, which had ever distinguished the people of this country. As the ministry refused to recede from their claims, and we refused to submit to them, a war necessarily ensued, which, after a severe conflict terminated in our independence.

This is one of the most remarkable events recorded in the history of nations. Compared with our enemies we were few in number – without an army or navy – naturally brave, but undisciplined and unarmed – we had few experience officers – possessed little property, except the soil and its appendages – were thinly scattered over a wide country – without an energetic government – without any band of general union, but mere advice and recommendation, and without any coercive method to raise money or levy troops. We were to contend with a nation opulent, numerous, powerful and warlike; furnished with all the apparatus of war, and in a situation to form alliances if necessary. Great was the disparity – we saw it. But we felt the justice and importance of our cause. We were encouraged by able patriots. We entered the lists, trusting in the power and addressing the throne of the Almighty – we were united – we raised armies without compulsion, and we supported them almost without means – they soon were able to face veteran troops on equal ground – they endured hardship and met danger without complaining – we astonished the ocean with ships of force – we from various sources procured arms, ammunition and all the furniture of war. In many encounters we had success; in disastrous seasons we maintained our courage – we captured whole armies of invaders – we formed an advantageous alliance – we reduced our enemies to the necessity of withdrawing their forces and acknowledging our independence – we negotiated peace, which was ultimately established on terms equal to our wishes and superior to our hopes. Through the whole scene the hand of heaven was conspicuous in the production of events by disproportionate means; and in raising up and employing in the great work of men of eminent ability and unshaken fidelity, whose names will naturally occur to your mind. Among these General George Washington and President Adams were distinguished; the former in the field, the latter in the cabinet. The one at the head of his army conducted the war to a successful issue; the other, with his colleagues, negotiated an advantageous peace.

Nor can we overlook the divine influence in directing the people to the formation and adoption of constitutions, which happily combine energy with liberty; and to the choice of men to administer them, whose wisdom and fidelity have in the main preserved peace and respectability abroad, and tranquility and order at home, promoted industry, restored public credit and mutual confidence and rendered the nation prosperous and happy. If we can judge of the goodness of a government from its good effects, and this is certainly the best criterion, we must approve our own in its construction and administration.

The progress of our country in population, wealth, navigation and learning, is beyond example; and this has been most conspicuous since the revolution.

The growth of the Plymouth colony was, at first, but slow. In four years after it began, there were in it but 180 persons and 32 houses. In thirteen years its inhabitants were not more than sufficient to populate a single town. In the space of forty years it had only twelve small towns, on saw mill and a bloomer. The other colonies made greater progress. In 1643 there were in Massachusetts thirty incorporated towns, including four then under its jurisdiction within the limits of New Hampshire. Some other plantations were begun. There are within what is now the State of Massachusetts nearly 300 towns, 500 worshiping assemblies, and 400 settled ministers. The county of Hampshire was erected in 1662. There were then only three towns, Springfield, Hadley and Northampton. Within the same territory, which included Berkshire, there are now more than 90 towns.

In 1665, according to the report of the general court to the king’s commissioners, there were, in Massachusetts, 4,400 militia, exclusive of those excused by age, infirmity and office; and probably from 25 to 30,000 souls. The inhabitants at the present time may amount to 500,000. According to the same report, the shipping belonging to the colony was not far from 5,000 tons. The shipping of Massachusetts, exclusive of Maine, is now more than 200,000 tons. In the beginning of the past century, we may probably suppose, New England contained upwards of 100,000 souls; the other colonies a greater number. Virginia alone in 1671, contained 46,0000 white inhabitants, and 2,000 slaves. In 1760 there were in New England half a million, in 1790 more than a million of inhabitants. At this time there are probably 13 or 1,400,000; and in the united 5 million or more.

Within the last seven years, Pennsylvania has increased in taxable more than one fifth, and is supposed to have increased in inhabitants in equal ration, and to contain 530,000 souls. Her slaves, in this time, have diminished more than half, and are now but about 1500.

Within a century have arisen six new governments, and four within a few years, where before was only an uncultivated wilderness. Husbandry and commerce, by their mutual aid, are rapidly increasing. The shipping of the United States exceeds that of any nation, except the British. The armed ships of all descriptions, public and private, are said to amount to 300. In case of a war, which should offer inducements to the enterprise for private adventurers, the number might soon be doubled. In the Louisbourg expedition, fifty-five years age, it was with difficulty that a squadron of 12 armed ships, the largest mounting 20 guns, could be collected from New England.

In the year 1771, the exports from all the British colonies in America, including Bermuda and the Bahamas, and the shipments from colony to colony, amounted to about 15 millions of dollars. In the year 1790, the exports from the United only, exclusive of the colonies which the British retain, and of the home shipments, amounted 18 million. In 1796 they exceeded 67 million; in 1799 the amounted nearly to 79 million. They have considerably increased in the year past. The value of exports, in the space of nine years, has more than quadrupled. New York alone in 1799 exported as much in value, as all the states nine years before. Our exports in one year amount to more than the national debt. It is owing to our increasing commerce that our husbandry is in so flourishing a state. Our farmers had never less cause of complaint. The revenue arising from all our resources, chiefly from our commerce, was in 1791 short of five millions, in 1799 it was twelve and a half millions of dollars; and in this whole period it has amounted to above seventy-seven millions. This has been sufficient to defray the current expense of government, pay the interest of the national debt, and make some reduction of the principal; and all this at a time when our commerce suffered largely by wanton depredations, and when our expenses were increased by two insurrections, by Indian wars, by the building and arming of ships for the protection of our trade, and by the supposed necessity of assuming a warlike attitude on land. If we should enjoy external peace, internal tranquility and a wise administration of government, our strength and opulence in half a century will almost exceed calculation.

About the commencement of the last century, there was only one college in America, and in that number of students did not rise to seventy. Now there are in New England six colleges some of which contain from 150 to 240 students; and more than double this number of colleges in the other States.

Our country has produced many eminent characters in all the departments of civil and social life

In the late war our military officers soon equaled those of Europe in personal bravery and tactical knowledge. Our commander in chief was an honor to his country and to human nature. His reputation is surrounded with a glory to which no European can approach.

Our public ministers in the treaties which they have negotiated have shown a diplomatic skill not inferior to that of the ablest foreign ministers.

In our legislative assemblies there are speakers whose extensive science and commanding eloquence would do honor to a British parliament. And in our judicial courts, the bench and bar may boast of characters which would fill with dignity a correspondent place in the king’s bench.

Some of our literary writers in theology, history, philosophy, poetry and other sciences, might appear with reputation and acquire celebrity on an European theatre. American publications within twenty years have been multiplied, some of which are read with attention on the other side of the Atlantic. Too many7, however are frivolous some are vile. The increase of printing offices indicates the diffusion of knowledge. Newspapers are circulated through the nation and read by almost every citizen. These, if executed with regard to truth and decency, are useful vehicles of information. But when they are basely prostituted to irreligion, falsehood, slander, sedition, anarchy and party intrigue, they are the greatest curse that a nation can suffer. The moderate price at which they are obtained, and the facility with which they are circulated give them a peculiar advantage speedily to disuse their poison through all the veins of the body. A free and independent press is highly beneficial; but a licentious one is abominable. The former deserves encouragement; the latter will meet the execration of the wise and virtuous. There is no way in which a people can more rapidly accelerate their corruption and misery, than by patronizing newspapers of the latter description.

The American Revolution has been productive of serious consequences to other countries. By means of the French army and navy, which co-operated with us in the latter part of our late war the sentiments of liberty were spread through France; and, concurring with other causes, produced a revolution there. The opposition made to this revolution by the neighboring powers has involved Europe in a war, which has exceedingly deranged her ancient system of politics. Though the immediate effects of this war have been extremely calamitous, and though the French revolution, instead of exalting, has almost extinguished the liberties of the people, yet we doubt not, that the great events, which have taken place in that hemisphere, will, in the hands of providence, be made the means of accomplishing the predictions of scripture concerning the happy state of the Church and the world. The present events wear the complexion which prophecy has impressed on those which are to precede that glorious issue.

We see the prophecies fulfilling. Popery has received a mortal wound and is tending to its exit. According to prophecy, the mahometan and the papal powers will fall nearly together. The same duration is prefixed for both. Mahometanism arose about the time that the bishop of Rome was declared universal head of the Church. These two systems of superstition are equal obstructions to the spread of Christianity. This never can generally prevail, while either of those systems stands in the way. The Turkish Empire has for some time been tottering. Its government, though despotic, is feeble and inefficient. The French have taken and still keep possession of Egypt. Passawan Oglou makes progress and gives terror to the Turkish government. He is probably assisted by the French and Russians. The Russians, who border upon and are enemies to the Turks, will probably soon make war upon them, and reduce till lower, their declining power. When popery and mahometanism have fallen, the two grand obstacles to the spread of the gospel will be removed. After this perhaps in about forty five years, if we rightly understand Daniel, a glorious reformation will begin to make its appearance. Previously, however there will be a great prevalence of infidelity. This, I fear, has not yet risen to his height, nor spread to its extent. It will be most bold and daring toward the commencement of grand reformation. The devil will come down with great wrath, when he sees that his time is short. Under the seventh vial in the Revelation, Babylon will completely fall. We are now supposed to be under the sixth vial perhaps near the last running of it. Under this we are warned, “Unclean spirits, the spirits of devils will go forth unto the kings of the whole world, and gather them to the battle of the great day of God Almighty.” These spirits of devils are supposed to be the malignant enemies of the gospel, who will apply every artifice to spread their pernicious sentiments and undermine the interest of Christ’s kingdom; and they will probably use force, as well as intrigue. This seems to be imported in the expression, “They will gather the kings to the battle,” Though they deny the right of rulers to support religion, they will call in their power to subvert it. They will, use every stratagem to put the power of the government into the hands of their own partisans, and to corrupt those in whom this power is vested. They will make a kind of open war against God. They will seem, for a while, to prevail against the friends of God and religion. This perhaps will be the slaying of the witnesses mentioned by Saint John. But these witnesses will not long lie dead. They will wonderfully rise up again and stand on their feet, to the terror of their enemies and astonishment of the world. On these enemies of the truth, awful judgments will now be executed thousands of them will be slain, and the remnant will be affrighted and give glory to God. Such a scene as we have described, prophecy instructs us, will precede the happy day.

“Blessed is he that watcheth and keepeth his garments.” Something of the kind seems already to have begun in Europe. Our safety will depend on our maintaining the religion of Christ, and standing firm against the machinations of its enemies. The gospel is a most benevolent and friendly institution: opposition to it must therefore proceed from a settled malignity of heart; and to what lengths this malignity may proceed, none can foretell. Let us not be shaken in mind, but stand fast in the Lord.

The 18th century has closed – and closed with an event, which, we hope, may be of happy consequence; a treaty of amity with the French. Of the merits of the treaty we pretend not to be judges. The disposal of it we leave to the continued authority. At least we flatter ourselves that it may lead to the termination of an unhappy controversy.

We wish this new century may begin with an event of more general importance, the establishment of a peace in Europe. Negotiations have been opened; but, I fear there is but a faint prospect of a pacific issue. The war has so deranged the ancient relations of the European powers, that an adjustment of their disputes will be extremely difficult; the satisfaction of their interfering aims will be utterly impossible. If necessity should compel them to a peace, it probably will be only a breathing spell to gather strength for war. This, if I mistake not, is that eventful period, in which there must be convulsions and over-turnings to prepare the way for the glory of the Redeemer’s kingdom. A people, among whom virtue and Christianity reign, will need no essential change; for the kingdom of Christ is already with them. O that we may be thus secured from a share in those judgments which will fall on a guilty world.

I will conclude this discourse with some general reflections.

1. In the dispensations of God toward his Church, we have full evidence of the truth of the gospel. From the beginning of the Christian institution; yea, from the beginning of the world, god has taken the Church under his protection. Mighty changes have been made in the world. Nations have risen, conquered, spread, declined and become extinct; others have succeeded them, followed their fortune, and shared their fate. But the Church has sustained and preserved; yea, to prevent its extinction God has often marvelously interposed. When we review God’s dealings toward it for eighteen centuries past, we plainly see that he has exercised over it a most peculiar care, and has directed the methods of his Providence in subservience to its interest. Can we doubt, then, whether the gospel be divine? On this the Church is founded: in this are foretold many of the great events which history records: evidence of its truth is constantly exhibited to our view. If the gospel is so much an object of God’s care, it must be highly important: indifference to it is a contempt of his grace; opposition is an outrage on his government.

2. Our subject gives us a humbling view of human corruption.

In all ages mankind, in a greater or less degree, have been favored with revelation. This, though in fact much confined, has been given under such circumstances, that, if men were as attentive to their eternal, as they are to their temporal interest, it would have prevailed universally. The partiality of it is no real objection against its divinity, but is a mortifying proof of human depravity. Were there the same attention to the concerns of futurity, as to those of the present life, the gospel would as easily and as rapidly spread among men, as discoveries in arts and sciences. It is a humiliating thought that when we need a remedy for our corruption, we are so obstinate in this corruption, as to spurn the remedy provided.

3. We see the importance of an attention to succeeding generations.

If the tendency of human nature is to corruption in sentiments and manners, it concerns us to communicate to our children just notions of religion, and to inculcate on them the virtues which it teaches. Let the generation on the stage faithfully discharge their duty to the next, and this again to the succeeding, and religion will be preserved. But the neglect of one generation opens the door to increasing corruption; and the neglect continued opens the door wider still; and in a succession of such generations the mounds will be broken down, and vice and error, breaking in like a flood, will overwhelm the land.

4. We see that the happiness of a nation depends on the existence of the Church among them.

This is God’s promise to his Church, “I am with thee to save thee: Though’ I make a full end of all nations, I will not make a full end of thee.” As the Church is under the protection of this promise, the nations which have a civil connection with her hence derive a national security. “Beautiful for situation is Mount Zion, the city of the great king; God is known in her palaces for a refuge.” Our security as a nation depends on our maintaining that religion which God, by a wonderful series of dispensations, has brought down to our days and put into our hands. If we neglect and despise it, and from us, our defense will depart with it, and we shall be made to feel, that it is an evil and bitter thing, that we have forsaken our God.

5. The events, which we have detailed, must awaken an expectation of still greater events.

The mighty drama is not closed. The day is coming, when the kingdom of Christ will overspread the world, and God will purge out of it all things that offend. But before this can take place, there is much to be done. God usually employs human agency in effecting the great purposes of his government, so that they seem to be brought forward in a natural way. He is now disposing the affairs of the world to introduce the mighty scene, and removing the obstacles which retard its appearance. Great alterations must be made before the gospel can have a general spread. Ignorant nations must be enlightened and arbitrary governments reformed. The paganism of heathens, the delusion of mahometans, the infidelity of the Jews, the superstition of papists, the corruptions of Protestants, the stupidity and formality of nominal Christians must all be removed. And all this must be a work of time. None of us can expect to see the glorious day foretold. It is our wisdom, however to seek and pray for such a state of religion among ourselves, as that which the world will hereafter enjoy. If we cannot see mankind as happy as we wish, yet let us be solicitous to obtain for ourselves that personal happiness, which religion offers. Let us diligently promote the faith and practice of religion within the circle of our influence – within the families in which we preside – within the societies of which we are members.

Through the goodness of God we have begun a new century. We saw not the beginning of that which is past, nor shall we see on earth the end of that which is begun. Great events have we seen, and great events will our children see. And there is one which we all must see, and which, as it concerns the individual, is more important than all that have passed before us – that within a short time, we must relinquish our earthly interests and connections, and remove, not from one clime, but from one world to another; must enter on a new state of existence; appear in presence of the Almighty Judge; receive our eternal destination to felicity or woe; dwell among spirits, holy or impure, according as our character is assimilated to the one, or the other – Good God! How amazing the thought! – To thine unbounded mercy we resort and here we rest. Compared with such a change, what is the revolution of a kingdom or the dissolution of an empire what multitudes have experienced such a change in the century past? What multitudes will experience the same in the century to come? Countless millions not yet in existence will, within a hundred years, come on the stage, act a part, and pass away to receive their retribution in another world. We have already come on the stage; our part is assigned us; our end will be according to our works. To us the gospel of salvation is given: whether our descendants will enjoy it, depends on our wisdom and fidelity. Let us cordially obey it, and faithfully hand it on to them. Thus we shall ensure our own salvation, and in the best manner contribute to theirs. Though we cannot in this low vale see all the vast events, with which the new century is pregnant, yet we may rise to a superior station, and thence behold them with admiration and joy. Though we shall not see the Church in its glory on earth, yet we may join a more glorious Church above, and thence look down on the wonders of Divine Providence toward the Church below, and join the Heavenly choir in ascribing glory and blessing to God for his great salvation to the faithful, and his righteous judgments on their enemies. Great and marvelous are thy works, Lord God Almighty: Just and true are all thy ways, thou King of Saints

A HYMN

Sung after sermon.

With wonder we survey they ways,

In which our God to men imparts

The blessings of his love; with praise

Our mouths are fill’d with joy our hearts.

From Heaven he sent his glorious son,

To dwell with men; for them to die;

From death he rais’d him to a throne,

With pow’r to rule through earth and sky.

Proud are the kingdoms of the world;

But though of wealth and pow’r they boast,

They all to ruin shall be hurl’d,

Rather than his Redeem’d be lost.

Rear’d by his hand, bought with his blood,

Firm stands his Church, though earth assail;

Through twice nine ages it has stood,

Nor will the gates of hell prevail.

Like Moses’ bush on Midian’s plains,

Oft has it been enwrapt in flame;

But unconsum’d it still remains,

Secur’d by Jesus’ mighty name.

By superstition’s madness driv’n,

To these Columbian wilds it fled;

Here nurtur’d by the care of Heav’n,

It , like a vine has grown and spread.

This vine, Dear Savior, nurture still;

Vile shoots prune off, but spare the root:

Increase it, till the land it fill

And bless the nations with its fruit.

With joy we contemplate the day,

When Christ shall through the earth be known:

Ye lin’ring years, come, roll away,

To speed the glories of his throne.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!