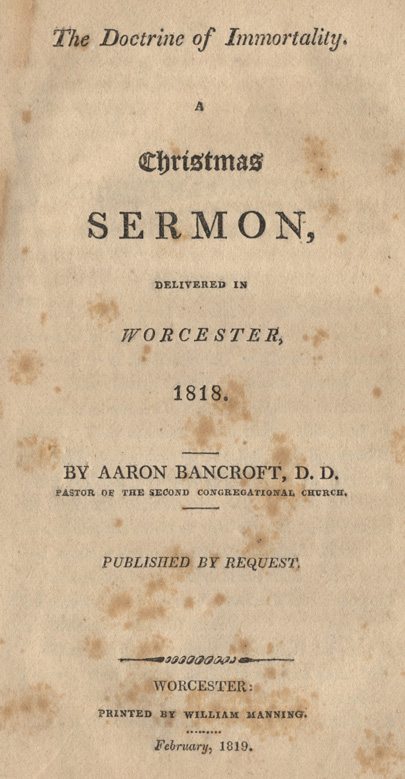

Aaron Bancroft (1755-1839) was a minute-man who served during the Revolution, fighting at Lexington and Bunker Hill. He graduated from Harvard in 1778 and was a missionary in Yarmouth, Nova Scotia for 3 years. Bancroft served as pastor of the Congregational Church in Worcester, MA (1785-1839). The following Christmas sermon was preached in1818 in Worcester by Rev. Bancroft.

The Doctrine of Immortality.

A

Christmas

SERMON

Delivered in

WORCESTER,

1818.

BY AARON BANCROFT, D. D.

PASTOR FO THE SECOND CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH.

A Christmas Sermon.

The human mind is prone to pass from one extreme to its opposite. This observation may be illustrated from the history of the Christian community. The Roman Catholic Church carried ceremonial observances in religious worship to extreme abuse. They canonized numerous saints, and appointed so many days to be religiously observed in honor of their memory, as greatly to int4erfere with the important business of society. Like the Pharisees of old, the rulers of this church, in its corrupt age, made religion essentially to consist in the superstitious observance of external forms; and public worship with them degenerated into a splendid but lifeless ceremonial service.

But when the English Church threw off the yoke of Popery, their rulers, in the opinion of many discerning and pious men, retained too many of the forms of the ecclesiastical establishment from which they separated. The ceremonies which they did preserve, were certainly enforced by measures which in their operation infringed the rights of private judgment, and violated the humane spirit of their religion.

Our ancestors, who fled from this imposition on conscience, associated with their disaffection to the dominating temper and the abusive practices of that hierarchy, a dislike to nearly all the circumstances common to its public services. Every instrument of music was excluded from houses of religious worship; and a form of ecclesiastical government and religious service was excluded from houses of religious worship; and a form of ecclesiastical government and religious service was adopted, the best suited, perhaps, to the infant state of the colony, but not fitted for a great and independent nation in the state of improved society.

Christmas was pre-eminently distinguished among the holy days of the Romish and the English church; and the general opposition of our forefathers to their superstitions and abuses was extended to this festival. They through several succeeding generations not only refused to join in the religious offices of the season, but they also scrupulously abstained on this anniversary from those articles of the table, which usually composed a part of a Christmas dinner.

We, their favored descendants, fondly cherish the highest veneration for their memories; we dwell with delight on their live of civil and religious liberty, on their piety and patriotism; our hearts are warmed by grateful recollections as often as we review the invaluable institutions which they have transmitted to us; and at the same time we rejoice that we are liberated from the prejudices which their situation rendered unavoidable Not feeling the pressure of that iron hand which bore heavily on them, we can calmly separate accidental circumstances from essential principles. With higher means of instruction, we can consistently drop the weak and indifferent appendages of their system, while we sacredly adhere to its sound and vital parts.

In respect to ceremonial observances, a more liberal spirit now prevails through our country. In many of our religious societies organs have been in introduced in church music; and in most of them other instruments are now used without giving offence. While, in the progress of society, all other institutions have their appropriate ornaments, many think, that if social worship be left without decoration, it will be destitute of those external attraction, which to a large portion of mankind are beneficial, if not necessary. And they imagine that embellishment may be introduced without corrupting the spirituality, or lessening the moral influence of public worship.

Situated as we are, may we not, without unreasonable bias, determine the degree of estimation in which Christmas services ought to be holden by a Christian community? The New Testament has not appointed anniversary services in commemoration of the birth of our Savior. If we celebrate this event, we should consider it as a privilege with which we are indulged, not as a duty divinely enjoined. This celebration is not by divine authority appointed; it is not by divine authority forbidden. Its expediency should be determined by its probable effects. We publicly commemorate the anniversary of our national independence; we publicly honor the memories of the benefactors of our country. Is it not then proper, that we should celebrate the advent of Emanuel into our world? Is any other event great in comparison with this? Has any other being appeared among men to whom we are under obligations of gratitude, when compared with him?

Should any object to the time of this celebration, on the plea,, that we have not conclusive proof respecting the particular day on which our Savior was born, our answer is, the objection on the point before us has no force. Christ the Savior was born into our world; whether we celebrate his appearance on the precise day of his birth, or on some other, to a religious purpose is a circumstance of no importance. The Christian community in general entertain the same opinion respecting the time; if the event be publicly noticed, it is convenient, and therefore desirable, that there should be uniformity in the day of celebration.

The useful purposes contemplated by the religious observances of the season are these : to direct our serious attention to the great salvation, which Jesus Christ descended from heaven to publish to a sinful world; to excite in us suitable returns of gratitude for the inestimable privileges we possess as his disciples; to animate us to sustain with firmness and consistency the Christian profession; to inspire us with diligence in the cultivation of the Christian graces and virtues; and to insure our perseverance in the path towards Christian perfection.

The passage of Scripture which I have chosen as the theme of our Discourse, will be found in

HOSEA xiii. 14. I will ransom them from the power of the grave; I will redeem them from death. O death, I will be thy plague. O grave, I will be thy destruction.

THOUGH these sublime declarations be considered as having a primary reference to the nation of Israel, yet, in their general sense, they may without violence be taken as expressive of the great doctrine of immortality, which Jesus Christ came into our world to establish and proclaim. In this doctrine we all have the deepest interest. Admit, that existence of endless duration, and of unchangeable happiness, is attainable by us, and all worldly objects lose their comparative worth. Admit, that the Christian path leads to the realms of glory, honor and immortality, and the motives to Christian piety and virtue are presented to the human mind, which all the temptations to the unlawful pursuits and to the inordinate indulgences of the world cannot weaken. Can we then, my Christian brethren, better improve the season, than in contemplating our title to eternal life by the promise of the Gospel? We then shall be excited to religious gratitude to him, who died that we might live forever; we shall establish ourselves in the resolution strenuously to exert ourselves to acquire the qualifications of the disciple of the Prince of Life; and shall, by the blessing of God, become prepared to passion in the way of salvation with joy and gladness.

From our text, we will,

1. Review in a cursory manner the history of the doctrine of immortality among the nations of the earth before the birth of our Savior.

2. Attend to the information of the Gospel on this important subject.

3. Consider the influence which the instruction and the promises of the Gospel ought to have on our dispositions and conduct.

1. To review the history of the doctrine of immortality among the nations of the earth before the birth of our Savior.

The expectation of a future state of existence has been common to men in every age of the world. Nations the most ignorant and barbarous discover this persuasion. Men, who appear to have bounded their inquiries by the simple wants of animal existence, express their belief of life beyond the grave. Whether these apprehensions naturally result from religious principles, interwoven into the human constitution principles, interwoven into the human constitution and which cause men, without the aid of revelation or philosophy, to rise superior to the threatening appearances of death, and to embrace the hope of immortality; or, whether these are traditionary notions, transmitted from the early age of the world, and which had their origin in divine communication, is not easy to determine. The unquestionable fact is, that men, in situations the most unfavorable for religious inquiries, have entertained the expectation of existence after death. Though they believe the human body to be corruptible; though they are the witnesses of the death of their friends, and see their bodies mingling with the dust; yet they imagine their deceased relations and acquaintances still to exist, and they suppose them existing with the same bodily shape, with the same appetites and passions, which they possessed on earth. Being unacquainted with the higher pleasures of an intellectual and moral nature, the heaven of the ignorant savage consists in the gratification of animal desires; and his expected happiness in a future world is merely the completion of his earthly wishes.

The theological systems of those Heathen nations which had made the greatest attainments in science and literature, were not favorable to the acquisition of religious knowledge, or the cultivation of the moral virtues. These systems contained many principles well calculated to make ignorant men the submissive subjects of civil government, and recommended a round of weak and debasing services, fitted, in the apprehension of a deluded people, to induce the Presiding Divinity propitiously to regard national prosperity and individual safety; but which possessed little to instruct inquiring mind respecting the nature of moral government, or to enlighten the man in rational views of futurity, who was anxiously desirious to look behind the curtain of death. A man might scrupulously fulfil every requisition of the established religion of Greece and Rome, and at the same time cherish the worst propensities of the human heart, and habitually indulge himself in the most impure acts of vice. The doctrines respecting futurity, publicly inculcated, were blended with extravagant fables and superstitious rites, and they did not furnish adequate motives to persuade men to discipline their passions, or soberly to govern their lives.

The reasonings of the Heathen philosophers never gave satisfaction on the subject of immortality. The wisest of them labored for the discovery of proofs to establish this interesting position in theology. Their arguments are plausible, and perhaps lay a foundation for the support of a good moral life, and for hope in death; but the greatest of them express uncertainty on the point, and acknowledge that adequate information can never be obtained, unless it should please God to send a messenger from heaven to publish to the family of man his future intentions respecting them. None of the Heathens sages had any apprehensions of the resurrection of the body; and many of them, in their reasonings on the doctrine of immortality, bewildered themselves with metaphysical distinctions, and darkened the subject by words without knowledge. Perhaps a candid and discerning man would rise from the perusal of all the dissertations composed by the moral philosophers of the old world on the doctrine of immortality, with a mind rather perplexed than enlightened; with his doubts and fears rather multiplied, than his belief and hope established. This appears to have been the state of the case in the Gentile world on the point before us. The natural reason and conscience of men direct their views to a future life, in which they will receive a reward corresponding with their present actions. Every man, learned and ignorant, perceives the influence of these principles. Moral philosophers stretched their powers to lay a stable foundation for the belief of that future existence of which they had a glimpse, and to acquire adequate views of that condition of being to which they aspired; but they did not succeed; they arrived not at a conclusion on which they could rely with certainty or satisfaction. In the vain attempt to define the human soul, and to explain the mode of its future existence, and the manner of its future exercises, they met with insuperable difficulties, and divided into various sects. Some of them, failing in the endeavor to support a favorite hypothesis by solid arguments, renounced their scheme, and with it the doctrine of immortality, and stifled the natural apprehensions of the human mind as erroneous.

The people of Israel possessed better means of instruction on the sublime doctrine of immortality, than had the Pagan nations around them. They were taught the unity, the holiness, and the universal supremacy of God. They had the fullest evidence of the super intendency of God over the affairs of men. Their history furnished them with examples of an immediate intercourse with the spiritual world; and the translation of Enoch and Elijah were fitted to raise their views to a higher state of being. I cannot therefore for a moment doubt, that the individuals among this people, who were distinguished for their piety, supported themselves, under the trials of the present life, by a belief of a future state of retribution, and died in the hope of a blessed immortality. Nor can I suppose, that the nation generally were destitute of the expectation of a future life. But we know that the Sadducees, not a small sect, totally rejected, even in the time of our Savior, the doctrine future existence : they said “that there is no resurrection, nor angel, nor spirit.” The Mosaick institution was preparatory to that of the Gospel. In the doctrine of immortality was but imperfectly revealed. Future rewards and punishments composed no part of the sanction of the law of Moses. Indeed, some learned and pious Christians are of the opinion, that was the doctrine is not to be found in this dispensation. We cannot with certainty say, that the devout Jews, who believed in a future state, adopted the opinion merely on the authority of their sacred books.

The result of our review then is this. The doctrine of the immortality of man was not established with moral certainty before the appearance of Jesus Christ in our world.

Let us,

2. Attend to the information of the Gospel on this important subject.

Christ has abolished death and brought life and immortality to light. Jesus, the Prince of Life, has dispersed the clouds which obscured our prospects of a future state. He has solved the doubts on this subject which perplexed the wisest of men. He has broken down the wall of partition between time and eternity, and presented the heavenly world to our view in all its glories. He has established the doctrine of a future retribution on a foundation that cannot be moved, made it an adequate support of a pious and virtuous life, and the sure ground of hope and joy in death. By his own resurrection he has given an earnest of the future resurrection of his disciples. Then the prophetical declaration of our text will be fully accomplished. “I am he,” says our Savior, “that liveth and was dead : and behold I am alive forever more, and have the keys of death.” “I am the resurrection and the life: he that believeth in me hath everlasting life, and I will raise him up at the last day.” “The hour is coming, in which all that are in their graves shall hear the voice of the Son of God, and come forth.” “The sea shall give up the dead that are in it; and death and the grave shall deliver up the dead that are in them.” “We must all appear before the judgment-seat of Christ, that every one may receive the things done in the body, according to that he hath done, whether it be good or bad.” Such is the language of the New-Testament on this subject.

Arguments in favor of immortality, drawn from the nature of the human soul, from the attributes of God, from the traces of a moral government visible in the present state and from every view which can be taken of natural religion, all have their place in the defense of Christianity, and help to make it the more credible. But the information of the Gospel on the doctrine of our future existence is most plain and direct. It is adapted to every capacity, and fitted to enlighten every mind. It is information, not given as the result of abstract reasoning and logical deduction, but it is given by the Parent of Life, and the moral Governor of the Universe; and he, in his goodness and mercy, has been pleased to confirm our faith in his divine communication, by raising his Son from the grave, whom he commissioned to publish the glad tidings of salvation to a guilty world. The future existence of men is exemplified to human view in the renewed life of the savior; and our belief of its reality may rest on a fact capable of proof like other facts — a fact made credible to us by the testimony of plain men, who were witnesses of its reality; and whose testimony is fortified by their general character, by the cheerful sacrifice of worldly interest and of life in support of their veracity, and by every circumstance which has attended the establishment and preservation of Christianity.

The enlightened, the confirmed Christian, cannot doubt his own immortality. He can never entertain fears of annihilation, from the mere contemplation of which our minds recoil in horror.

The more forcibly to show the value of the instruction of the Gospel, permit me to place before you in contrast, the views of a Heathen and of a Christian philosopher on our subject. We will select, as an example, the moral sage who was a master of all Grecian and Roman learning, who wrote on the nature of the Presiding Divinity, on moral virtue, and on the immortality of man, and who, in every accomplishment, stood pre-eminent among the great and the wise. Cicero, the ornament and the boast of Rome, observes, that one time a future state seemed to him to be fully proved; that at another, all his arguments appeared to vanish and he was left in doubt. He remarks, that it was in his retired moments, and whilst he devoted himself to deep meditation, that he felt satisfied with the result of his researches, and without reserve admitted the belief of immortality; and that, as soon as he entered society, other feelings arose, and amidst worldly pursuits the expectation of a future life passed from his mind. Writing to a friend, Cicero expresses himself in the following manner: — “I do not see, why I may not venture to declare freely to you what my thoughts are concerning death. Perhaps I may discover, better than others, what it is , because I am now, by reason of my age, not far from it. I believe that the Fathers, those eminent persons and my particular friends, are still alive, and that they live the life which only deserves the name of life. Nor has reason only and disputation brought me to the belief, but the famous judgment and authority of the chief philosophers. O glorious day! when I shall go to the council and assembly of spirits; when I shall go out of this tumult and confusion; when I shall be gathered to all those brave spirits who have left the world; and when I shall meet the greatest and best of men. But if, after all, I am mistaken herein, I am pleased with my error, which I would not willingly part with, while I live; and if, after my death, I shall be deprived of all sense, I have no fear of being imposed upon and laughed at in the other world for this my mistake.”

Here the moral philosopher of Rome mentions a future state of being as a probable truth, and as the object of his hope, but not as a doctrine founded on such clear proof as to fix his unshaken faith. Even this probability draws from him an impassioned eulogy on its felicity. But his doubts damp the ardor of his feelings, and he derives security to his hope from the consideration, that if the present life should close human existence, annihilation will free him from ridicule.

St. Paul, the apostle of Jesus Christ, was also a believer in the doctrine of man’s immortality. He entertained the hope of being admitted, at death, not only to the spirits of just men made perfect, but also to the assembly of angels, to the company of his Divine Master, and to the presence of God. But his opinion rested not on that slight evidence which, thought sufficient to charm the imagination under the shade of philosophy, or in the silent hour of meditation, yet did not furnish a principle to support the mind under the conflicts of the world. The belief of eternal life was so fully established in his mind, as to become the first object of desire, and the goal to which every exertion was directed. To preach the doctrine of the resurrection and of eternal life, he was ready to sacrifice all worldly enjoyments; and while suffering the heaviest evils incident to the present state of man, he declared, “None of these things move me, neither count I my life dear unto myself, so that I might finish my course with joy, and the ministry of the Lord Jesus, to testify the Gospel of the grace of God.” Paul also, has left a treatise on death and immortality. In it he expresses neither doubt nor anxiety : he declares the proof of future existence to be complete and satisfactory : so fully was his mind possessed of the expectation of immortal life, that to him it became a present reality : a view of its glories transp0orts his should; and he breaks forth in songs of joy and triumph — “O! death where is thy sting? O! grave where is thy victory? The sting of death is sin, and the strength of sin is the law; but thanks be to God, who giveth us the victory through Jesus Christ our Lord.”

We will,

3. Consider the influence which the instruction and the promises of the Gospel ought to have on our dispositions and conduct.

Whether we consider the object of the instruction and promises of the Gospel, or the character of the Being who gave them, we shall perceive the value of our Christian privileges, and feel our obligation to improve them. The object is a blessed immortality; their author Christ, the Son of God to the goodness and mercy of God are we indebted for the scheme of our salvation. God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have ever lasting life. But Christ devoted himself, as Mediator, to the execution of the purposes of divine grace and mercy. The angels of heaven were the heralds of the advent of Emanuel; and proclaiming his birth, they gave glory to God on high, and published peace and good will to men. In the high concern of our salvation, Jesus appeared in the nature of man, subjected himself to all the wants of humanity, endured the contradiction of sinners, and yielded himself the victim of the cross. Grateful to God for the gifts of his Son, grateful to Christ for his voluntary mediation, Let us under the influence of our religion, conform ourselves to the divine image, and imitate the example of the Saviour. God in his goodness has given us an assurance of future life : do we with indifference receive the information? In mercy he has by his own Son promised us endless felicity in a future world, on conditions which rove that he consults our present as well as our immortal happiness : can we be unmoved by the gift?

Respecting the influence which religion ought to have on our tempers and practices we may take useful lessons, even from those whose ignorance and superstition we justly compassionate. The infatuated Pagan, in compliance with the requisitions of his system, with alacrity subject himself to the severest bodily tortures, and with apparent delight offers his life in sacrifice to his idol deity. The deluded follower of Mahomet never supposes his religious duty performed, till he has made a painful journey to Mecca, and worshipped at the tomb of his prophet. Shall we Christians, then, we who are instructed in all truth pertaining to eternal life and vindicated into perfect liberty, refuse gratefully to acknowledge Jesus Christ as our Lord and Master? Shall we neglect to observe those gracious directions which are designed to transform us into a likeness of his perfect character, to make us in disposition the most amiable, in practice the most benevolent and to qualify us for the society of heaven?

May the example of primitive Christians more especially, enliven our diligence in the path of piety and virtue, and fortify our minds with resolution to sustain the conflicts of our probationary course. Animated by the hope of the Gospel, the apostles of our Lord subjected themselves to all terrors of persecution, not accepting deliverance, that they might obtain a better resurrection. The great body of the first converts to our religion gave full evidence of their faith in the promises of the gospel, and clearly manifested that it had a salutary influence on their tempers and lives. These died in the faith, not having received the promises; but seeing the afar off, were persuaded of their reality, embraced them as the objects of their supreme dependence, and in consequence professed themselves strangers and pilgrims on earth. The motives and assistances, which supported them, are presented to our minds, and our course is free from many of the difficulties and dangers, with which theirs was beset. Let us then, imitate those who, through faith and patience have inherited the promises.

As Christians, we are bound to give a fair exemplification of our religion before the world. As candidates for immortality, it is our first duty and our highest interest to walk worthily of our Christian vocation; for the salvation of our souls is suspended on the improvement of our privileges as the disciples of Jesus Christ. May our religion in its life dwell in our hearts; may it in all its beauty and lustre shine in our lives.

In the consciousness of sincerity and diligence in the high concerns of our probation, let us open our minds to the hope and the joy, to which the Christian character is entitled. Disposed to approach the light of truth, and make it manifest that our deeds are wrought in God, a dependence on the promises of the Gospel being in us the principle of Christian life, let not debasing fear enter into our religious services; but through all worldly vicissitudes, let us rejoice in the Lord, and joy ourselves in the God of our salvation. Not resting satisfied with the things that are seen, but seeking first the kingdom of God and its righteousness, may we with supreme delight consider ourselves as children of God; and if children, then heirs, heirs of God, and joint heirs with Christ, unto an inheritance that is incorruptible, undefiled, and that will not fade away. — Amen.

*Originally Posted: Dec. 25, 2016

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!