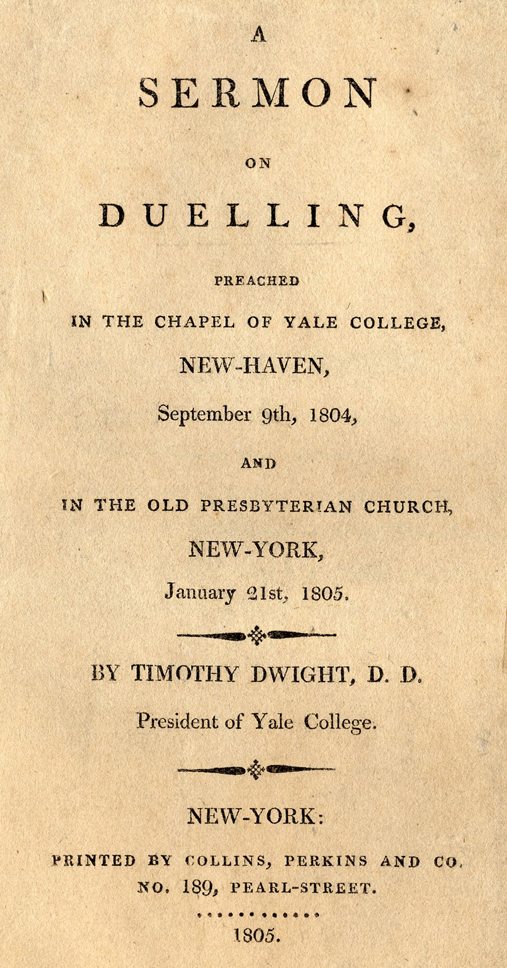

Timothy Dwight (1752-1817) graduated from Yale in 1769. He was principal of the New Haven grammar school (1769-1771) and a tutor at Yale (1771-1777). A lack of chaplains during the Revolutionary War led him to become a preacher and he served as a chaplain in a Connecticut brigade. Dwight served as preacher in neighboring churches in Northampton, MA (1778-1782) and in Fairfield, CT (1783). He also served as president of Yale College (1795-1817). Dwight preached this sermon in 1804 and again in 1805 on dueling.

SERMON

ON

D U E L L I N G,

PREACHED

IN THE CHAPEL OF YALE COLLEGE,

NEW-HAVEN,

September 9th, 1804,

AND

IN THE OLD PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH,

NEW-YORK,

January 21st, 1805.

BY TIMOTHY DWIGHT, D. D.

President of Yale College.

ADVERTISEMENT.

The Gentlemen to whom the publication of the following Discourse was entrusted, think proper to mention, that a cop of it was requested for the Press, by a number of the Citizens both of New-Haven, and of New-York, who heard it preached, and who considered it as calculated to be extensively useful.

New-York, May 20, 1805.

When this Sermon was delivered, it was prefaced with a declaration, of the following import.

The following discourse will not intentionally apply to any facts or persons; it being the Preacher’s design to examine principles, and not to give characters.

SERMON

ON

D U E L L I N G.

A man that doeth violence to the blood of any person, shall flee to the pit; let no man stay him.

This passage of scripture is a republication of that general law concerning homicide, which is recorded in Genesis 9. 5, 6. But surely your blood of your lives will I require: at the hand of every beast will I require it, and at the hand of man; at the hand of every man’s brother will I require the life of man. Whoso sheddeth men’s blood, by man shall his blood be shed: for in the image of God made he man. This law was published at the time when the killing of beasts for food was permitted. No time could have been equally proper. As the shedding of animal blood would naturally remove the inherent horror at destroying life, and prepare men to shed the blood of each other; the law became indispensable for the prevention of this crime, from the beginning. It ought to be observed, that the detestation with which God regards this sin, is marked with a pen of iron in that singular declaration: “At the hand of every beast will I require it.” If homicide is so odious in the sight of God, as to expose the unconscious brute, which effected it, to the loss of his own life, as an expiation; with what views must He regard a man, a rational agent, formed in his own image, when accomplishing the death of his brother with design, from the indulgence of malice, and in the execution of revenge?

As this original law was given to Noah, the progenitor of all post-diluvian men, it is evidently binding on the whole human race. Every nation has accordingly felt its force, and executed it upon the transgressor.

In the text, the same law is promulged with one additional injunction—“He shall flee to the pit, let no man stay him.” However strongly the past services of the criminal, or the tender affections of his friends, may plead for his exemption from the sentence; no man, from any motive, or with any view, shall prevent, or even retard, his progress towards the punishment required. To this punishment God has consigned him, absolutely, and with his own voice. No consideration, therefore, can prevent, or hinder, the execution.

A sober man would naturally conclude, after reading these precepts, that, in every country, where their authority is acknowledged to be divine, homicide would in all cases, beside those excepted expressly by God, be invariably punished with death. At least, he would expect to find all men in such countries agreeing, with a single voice, that such ought to be the fact; and uniting, with a single effort, to bring it to pass. Above all, he would certainly conclude, that, whatever might be the decision of the vulgar, and the ignorant, there could be but one opinion, in such countries, among those who filled the superior ranks of society.

How greatly then, must such a person be astonished, when he is informed, that in Christian countries only, and in such countries among those only, who are enrolled on the list of superiority and distinction, homicide, of a kind nowhere excepted by God from this general destiny, but marked with all the guilt of which homicide is susceptible, is not only not thus punished, but is vindicated, honoured, and rewarded, by common consent, and undisguised suffrage!

The views which I entertain of dueling, may be sufficiently expressed under the following heads:

The Folly,

The Guilt, and

The Mischiefs, of this crime.

Duelling is vindicated, so far as my knowledge extends, on the following considerations only: That it is

A punishment,

A reparation, and

A prevention of injuries; and

A source of reputation to the parties.

If it can be shewn to be neither of these, in any such sense as reason can approve, or argument sustain; if it can be proved to be wholly unnecessary to all these purposes, and a preposterous method of accomplishing them; it must evidently fail of all vindication; and be condemned as foolish, irrational, and deserving only of contempt.

As a punishment of an offence, which for the present shall be supposed to be a real one, dueling is fraught with absurdity only. If a duel be fought on equal terms, the only terms allowed by duelists, the person injured exposes himself, equally with the injurer, to a new suffering; always greater in truth, and commonly in his own opinion, than that which he proposes to punish. The injurer only ought to suffer, or be exposed to suffering. No possible reason can be alleged, why the innocent man should be at all put in hazard. Were tribunals of justice to place the injured party, appealing to them for redress, in the same hazard of being obliged to pay a debt, with the fraudulent debtor; in the same danger of suffering a new fraud, with the swindler; or in an equal chance of suffering a second mayhem, with the assaulter of his life; or were they to turn him out on the road, to try his fortune in another robbery, with the highwayman; what would common sense say of their distributions? It would doubtless pronounce them to have just escaped from bedlam; and order them to be strait-waistcoated, until they should recover their reason. Here the injured person constitutes himself his own judge; and resolves on a mode of punishment, which, if ordered by any other umpire, he would reject with indignation! “What!” he would exclaim; “am I, because I have been injured once, to be injured a second time? And is my enemy, because he has robbed me of my character, to be permitted also to rob me of my life?” Let it be remembered, that the decision is not the less mad, because it is voluntarily formed by himself. He who wantonly wastes his own well-being, is of all fools the greatest.

As a reparation, duelling has still less claim to the character of rational. What is the reparation proposed? If it be anything it must consist either in the act of fighting, or in the death of the wrong-doer. If the injury be a fraud, neither of these will restore the lost property; if a personal suffering, neither can restore health; nor renew a limb, or a faculty. Or if the wrong be an injury to the character, it cannot need to be asserted, that neither fighting as a duelist, nor killing the wrong-doer, can alter at all the reputation which has been attacked. The challenger has, perhaps, been charged with lying. If the charge is just, he is a liar still. If it be known to be just, neither fighting, nor killing his antagonist, will wipe off the stain. The public knew him to be a liar before the combat; with the same certainty they know him to be such after the combat. What reparation has he gained? No one man will believe the story the less, because he has fought a duel, or killed his man. If, on the other hand, the charge is false; fighting will not, in the least degree, prove it to be so. Truth and falsehood must, if evinced at all, be evinced by evidence; not by fighting. In the days of knight-errantry this method of deciding controversies had, in the reigning superstition, one rational plea, which now it cannot claim. God was then believed to give success, invariably, to the party which had justice on its side. Modern duellists neither believe, nor wish, God to interfere in their concerns.

The reparation enjoyed in the mere gratification of revenge, will not here be pleaded, because duellists disclaim with indignation, the indulgence of that contemptible passion. In the progress of the discourse, however, this subject will be further examined.

As a prevention of crimes generally, it is equally absurd. I acknowledge readily, that the fear of and suffering will, in a greater or less degree, prevent crimes; and that men may, in some instances, be discouraged from committing private injuries by the dread of being called to an account in this manner. But these instances will be few; and this mode of preventing injuries, therefore, almost wholly ineffectual. Duelling is always honourable among duellists; and, to be generally practiced, must be generally esteemed honourable. That which is honourable will always be courted. The danger to life will, therefore, recommend dueling, to most men, instead of deterring from it. None, who call themselves men of honour, ever shew any serious reluctance to give, or accept, a challenge. All are brave enough to hazard life, whenever the hazard becomes a source of glory. Every savage, that is, every man in a state of nature, will fight, because it is glorious. Civilized men have exactly the same natural character. Persuade them that it is glorious to give and accept challenges, and to fight duels, and few or none of them will hesitate. The dread of danger, appealed to, and relied on, in this case, is therefore chiefly imaginary. Few persons will, ultimately, be prevented from doing injuries by the practice of dueling. Affronts, on the contrary, will be given, merely to create opportunities of fighting. Fighting, in the case supposed, is glory; and to acquire glory men will make their way to fighting through affronts, injuries, and every other course of conduct, necessary, or believed to be necessary, to the end. This fact in the case of humbler and more vulgar battles has long been realized. Many a bully spends a great part of his life in fighting; and will at any time abuse those, with whom he is conversant, not from malice or revenge, but merely to provoke them to battle, that he may obtain the honour of fighting. The nature of all classes of men is the same; and polished persons will do the same things, which are done by clowns, without any other difference than that which exists in the mode. The clown will fight vulgarly; the polished man genteelly: the provocations of the clown will be coarse; those of the gentleman will be more refined. With this dissimilarity excepted, the conduct of both will be the same; but as the gentleman, will feel the sense of glory more exquisitely, so he will seek it with more ardour, and will do wanton injuries with more frequency, and less regret. Thus the ultimate effect will be to increase, and not to prevent, injuries; and the extent of the increase cannot be measured. Besides, injuries so slight as to be ordinarily disregarded; nay imaginary and unintended injuries, will, amidst the domination of such pride and passion as regulate this custom, be construed into serious abuses; and satisfaction will be demanded with such imperiousness, as to preclude all attempts at reparation, on the part of the offender; lest, in the very offer of them, he should be thought to forfeit the character of an honourable man. Wherever fighting becomes the direct and chief avenue to glory, no occasion on which it may be acquired will be neglected. The loss of any opportunity will be regarded of course as a serious loss; and the neglect of the least, as a serious disgrace. The mind will therefore be alive, vigilant, and jealous, lest such a loss, or such a disgrace, should be incurred. Almost everything, which is either done, or omitted, will by such a mind be challenged as an affront, and resented as an injury. Thus the injuries, which will be felt, will be incalculably multiplied. To what a condition will this reduce society!

But dwelling is considered as a source of reputation. In what does the reputation, conferred by it, consist?

“The duelist is a brave man.” So is the highwayman; the burglar; the pirate; and the bravo, who derives his name from gallant assassination. Nay the bull-dog is as bold as either. Bravery is honourable to man, only when exerted in a just, useful, rational cause; where some real good is intended, and may hopefully be accomplished. In every other case it is the courage of a brute. Can a man wish to become a competitor with an animal?

But this claim to bravery is questioned. If from the list of duellists were to be subtracted all those, who either give, or receive, challenges from the fear of being disgraced by the omission, or refusal; how small would be the remainder! But is acting from the fear of disgrace, merely, to be regarded as bravery in the honourable sense; or as courage in any sense? Is it not, on the contrary, simply choosing, of two evils, that, which is felt to be the least? Is there any creature which is not bold enough to do this?

Genuine bravery, when employed at all, is always employed in combating some real evil; something which ought to be opposed. When public opinion is false and mischievous, it will of course meet, resolutely, public opinion; and dare nobly to stem the torrent, which is wasting with its violence the public good. Genuine bravery would nobly disdain to give, or receive, a challenge; because both are pernicious to the safety and peace of mankind. No man is truly great, who has not resolution to withstand, and will not invariably and undauntedly withstand, very false and ruinous public opinion.

But suppose it were really reputable in the view of the public; the question would still recur with all its force—Is it right? Is it agreeable to the will of God? Is it useful to mankind? No advance is made towards the defence of dueling, until these questions can be answered in the affirmative. The opinion of the public cannot alter the nature either of moral principles, or of moral conduct. In the days of Jeroboam, the public opinion of Israel decreed, and supported, the worship of two calves; and, both before and afterward, sanctioned the sacrifice of children to Moloch. The public opinion at Carthage destined the brightest and best youths of the State as victims to Saturn. In a similar manner public opinion has erred, endlessly, in every age and country. An honest and brave man would, in every such case, have withstood the public opinion; and would always firmly resolve, with Abdiel, to stand alone, rather than fall with multitudes. He who will not do this, when either the worship of a stock, the immolation of a human victim, or the murder of his fellow men, is justified by public opinion, is not only devoid of sound principles, but the subject of miserable cowardice. It is a mockery of language, and an affront to common sense, to call him, who, trembling for fear of losing popular applause, sacrifices his faith and his integrity to the opinion of his fellow men, by any other name than a coward.

But duellists claim the character of delicate and peculiar honour. On what is this claim founded? Are they more sincere, just, kind, peaceable, generous, and reasonable, than other men? These are the ingredients of an honourable character. They themselves cannot deny it. That some men, who have fought duels have exhibited greater or less degrees of this spirit, I shall not hesitate to acknowledge. Men of real worth have undoubtedly been guilty of this folly and sin, as well as of other follies and other sins. But these men derived all their worth from other sources; and gained all that was honourable in their minds, and lives, by the character which they sustained as men, and not as duellists. As duelists, they fell from the height, to which they had risen. He, who will explain in what the honour or the delicacy of the spirit of duelling consists, will confer an obligation on his fellow men; and may undoubtedly claim the wreath due to superior intellect.

On the contrary, how generally are duellists haughty, overbearing, passionate, quarrelsome, and abusive; troublesome neighbours, uncomfortable friends, and disturbers of the common happiness? Their pretensions to honour and delicacy are usually mere pretensions; a deplorable egotism of character, which precludes them from all enjoyment, and prevents those around them from possessing quiet, and comfort, unless everything is conformed to their vain and capricious demands.

There is neither delicacy nor honour, in giving or taking affronts easily and suddenly; nor in justifying them on the one hand, nor in revenging them on the other. Very little children do all these things daily, without either honour or delicacy, from the mere impulse of infantine passion. Those who imitate them in this conduct, resemble them in character; and are only bigger children.

“But duelling is reputable in the public opinion.” I have already answered this declaration; but I will answer it again.

Who are the persons of whom this public is constituted? Are they wise and good men? Can one wise and good man, unquestionably wise and good, be named, who has publicly appeared to indicate duelling? If there were even one, his name would, ere this, have been announced to the world. This public is not then formed of such men, and does not include them in its number. Is it formed of the mass of mankind; either in this, or any other, civilized country? I boldly deny, that the generality of men, in any such country, ever justified duelling, or respected duellists. Let the appeal be made to facts. In this country, certainly, the public voice is wholly against the practice. Some persons, who have fought duels, have unquestionably, been here respected for their talents, and their conduct; but not one for duelling. The proof of this is complete. This part of their conduct is never the theme of public, and hardly ever of private, commendation. On the contrary, it is always mentioned with regret, and generally with detestation. Who then is this public? It is the little collection of duellists; magnified by its own voice, as every other little party is, into the splendid character of the public. That duellists should pronounce duelling to be reputable, cannot be thought a wonder, nor alleged as an argument.

“But it is dishonourable not to give a challenge when affronted; and to refuse one, when challenged. Who can endure the sense of shame, or consent to live in infamy? What is life worth without reputation; and how can reputation be preserved, as the world now is, without obeying the dictates of this custom?”

This, I presume, is the chief argument, on which duelling rests; and by which its votaries are, at least a great part of them, chiefly governed. Take away the shame of neglecting to give, or refusing to accept, a challenge; and few men would probably enter the field of single combat, except from motives of revenge.

On this argument I observe, that he, who alleges it, gives up the former arguments, of course. If a man fights, to avoid the shame of not fighting, he does not fight, to punish, repair, or prevent, an injury. If the disgrace of not fighting is his vindication for fighting, then he is not vindicated by any of these considerations; nor by that of delicate honour, nor by anything else.

The real reason, and that on which alone he ultimately relies for his justification, is, that if he does not fight he shall be disgraced; and that this disgrace is attended with such misery, as to necessitate, and justify his fighting.

In alleging this reason as his justification, the duel list gives up, also, the inherent rectitude of duelling; and acknowledges it to be in itself wrong. Otherwise he plainly could not need, nor appeal to, this reason, as his vindication. The misery of this disgrace, is therefore, according to his declaration, such, as to render that right, which is inherently, and which but for this misery would still be, wrong, or sinful.

This is indeed a strange opinion. God has, and it will not often be denied that he has, prohibited certain kinds of conduct to men. These he has absolutely prohibited. According to this opinion, however, he places men by his providence in such circumstances of distress, that they may lawfully disobey his prohibitions; because, otherwise, they would be obliged to endure intolerable misery. Has God, then, published a law, and afterwards placed men in such situations, as to make their disobedience to it lawful? How unreasonably, according to this doctrine, have the scriptures charged Satan with sin? His misery, as exhibited by them, is certainly more intolerable than that, which is here professed, and of course will warrant him to pursue the several courses, in which he expects to lessen it. This is the present plea of the duelist; Satan might make it with double force.

Had the Apostles bethought themselves of this argument, they might, it would seem, have spared themselves the scorn, the reproach, the hunger, the nakedness, the persecution, and the violent death which they firmly encountered, rather than disobedience to God. Foolishly indeed must they have gone to the stake, and the cross, when they might have found a quiet refuge from both in the mere recollection, that the loss of reputation was such extreme distress, as to justify him who was exposed to this evil, in any measures of disobedience, necessary in his view to secure his escape.

What an exhibition is here given of the character of God? He has published a law, which forbids homicide; a law universally acknowledged to be just; and particularly acknowledged to be just in the very adoption of this argument. At the same time, it is in this argument averred, that he often places his creatures in such circumstances, that they may lawfully disobey it. Of these circumstances every man is considered as being his own judge. If then any man judge, that his circumstances will justify his disobedience, he may, according to this argument, lawfully disobey. If the argument were universally admitted, how evident is it, that every man would disobey every law of God, and yet be justified. Obedience would therefore vanish from men; the law become a nullity; and God cease to govern, and be unable to govern, his creatures. This certainly would be a most ingenious method of annihilating that law, every jot and tittle of which he has declared shall stand, though to fulfill it heaven and earth shall pass away.

On the same ground might every man, in equal distress, seek the life of him who occasioned it, however innocently, and hazard his own. But poverty, disappointed ambition, and a thousand other misfortunes, involve men in equal sufferings; as we continually see by the suicide, which follows them. Of these misfortunes, generally, men, either intentionally, or unintentionally, are the causes. He, therefore, who causes them, may, on this ground, be lawfully put to death by the sufferer. What boundless havoc would this doctrine make of human life; and how totally would it subvert every moral principle!

How different was the conduct of St. Paul, in sufferings inestimably greater than those here alleged! Being reviled, says he, we bless; being defamed, we entreat. Thus he acted, when, as he declares in the same passage, he was hungry and thirsty, and naked, and buffeted, and had no certain dwelling place.

But what is this suffering? It is nothing but the anguish of wounded pride. Ought, then, this imperious, deceitful, debasing passion to be gratified at the expense of murder, and suicide? Ought it to be gratified at all? Is not most of the turpitude, shame, and misery, of man the effect of this passion only? Angels by the indulgence of this passion lost heaven; and the parents of mankind ruined a world.

“But a good name is by the Scriptures themselves asserted to be an invaluable possession.” It is. But what is a good Name, in the view of the Scriptures? It is the Name, which grows out of good principles, and good conduct. It is the result of wisdom and virtue; not of folly and sin; a plant brought down from the heavens, which will flourish, and blossom, and bear fruit forever.

“But is not the esteem of our fellow-men an inestimable enjoyment? And have not wise men, in every age of the world, given this as their opinion?” The esteem, let me ask, of what men? The esteem of banditti is certainly of no value. The character of the men is, therefore, that which determines the worth of their esteem. The esteem of wise and good men is undoubtedly a possession, of the value alleged; particularly, because it is given only to wise and good conduct. If you covet esteem then, merit it by wisdom and virtue; and you will of course gain the blessing. By folly and guilt you can gain no applause, but that of fools and sinners; while you assure yourself of the contempt and abhorrence of all others.

I shall conclude this part of the discussion with the following summary remarks.

Duelling is eminently absurd, because the reasons, which create the contest, are generally trivial. These are almost always trifling affronts, which a magnanimous man would disdain to regard. A brave and meritorious Officer in the British army was lately killed in a duel, which arose of the fighting of two dogs.

As an adjustment of disputes, it is supremely absurd. If the parties possess equal skill, innocence and crime are placed on the same level; and their interests are decided by a game of hazard. A die would better terminate the controversy; because the chances would be the same, and the danger and death would be avoided. If the parties possess unequal skill, the concerns of both are committed to the decision of one; deeply interested; perfectly selfish; enraged; and precluded by the very plan of adjustment from doing that which is right, unless in doing it he will consent to suffer an incomprehensible evil. To avoid this evil he is by the laws of the controversy justified in doing to his antagonist all the future injustice in his power. Never was there a more improper judge, nor a more improper situation for judging. To add to the folly, the very mode of decision involves new evils; so that the injustice already done can never be redressed, but by doing other and greater injustice. 1

Finally, it is infinite folly, as in every duel, each party puts his soul, and his eternity, into extreme hazard, voluntarily; and rushes before the bar of God, stained with the guilt of suicide and with the design of shedding violently the blood of his fellow-man.

The guilt of dueling involves a train of the most solemn considerations. An understanding, benumbed by the torpor of the lethargy, only, would fail to discern them; a heart of flint to feel them; and a conscience vanquished, bound, and trodden under foot, to regard them with horror.

Duelling is a violation of the laws of Man. “Submit to every ordinance of man for the Lord’s sake,” is equally a precept of reason and revelation. The Government of every country is the indispensable source of protection, peace, safety, and happiness, to its inhabitants; and the only means of transmitting these blessings, together with education, knowledge, and religion, to their children. It is therefore a good, which cannot be estimated. But without obedience to its laws no government can continue a moment. He, therefore, who violates them, contributes voluntarily to the destruction of the government itself, and of all the blessings which it secures.

The laws of every civilized country forbid duelling, and forbid it, in its various stages, by denouncing against it severe and dreadful penalties; thus proving, that the wise and good men of every such country have, with one view, regarded it as an injury of no common magnitude. The duelist, therefore, openly, and of system, attacks the laws, the peace, and the happiness, of his country; loosens the bonds of society; and makes an open war on his fellow-citizens, and their posterity.

At the same time he takes the decision of his own controversies out of the hands of the public, and constitutes himself his own judge and avenger. His arm he makes the umpire of all his concerns; and insolently requires his countrymen to submit their interests, when connected with his own, to the adjudication of his passions. Claiming and sharing all the blessings of civilized society, he arrogates, also, the savage independence of wild and brutal nature; wrests the sword of justice from the hand of the magistrate, and wields it, as the weapon of an assassin. To him government is annihilated. Laws and trials, judges and juries, vanish before him. Arms are his laws, and a party his judge; his only trial is a battle, and his hall a field of blood.

All his countrymen have the same rights which he has. Should they claim and exercise what he claims, what would be the consequence? Every controversy, every concern of man would be terminated by the sword and pistol. Civil war, war waged by friends and neighbours, by fathers, sons, and brothers; a war of that dreadful kind which the Romans denominated a tumult, would spread through every country: a war, in which all the fierce passions of man would be let loose; and wrath and malice, revenge and phrenzy would change the world into a dungeon filled with maniacs, who had broken their chains, and glutted their rage with each other’s misery. Thus duelling, universally adopted, would ruin every country, destroy all their peace and safety, and blast every hope of mankind. Who but a fiend could willingly contribute to this devastation?

The guilt begun in the violation of the laws of man, is finished in the violation of the laws of God. This awful Being, who gave us existence, and preserves it; who is everywhere, and sees everything; who made, and rules, the universe; who will judge, and reward, both angels and men; and before whom every work, with every secret thing, shall be brought into judgment; with his own voice proclaimed to this bloody world, from Mount Sinai, Thou shalt not kill. The command, as I explained it in this place, the last season, forbids killing absolutely. No exception, as I then observed, can be lawfully made to the precept, except those which the lawgiver has himself made. These, I farther observed, are limited to killing beasts, when necessary for food, or plainly noxious; and putting man to death by the sword of public justice; or in self-defence; whether private or public: this being the only ground of justifiable war. As these are the sole exceptions, it is clear that duelling is an open violation of this law of God.

The guilt of duelling in this view is manifold; and in all its varieties is sufficiently dreadful to alarm any man, whose conscience is susceptible of alarm, and whose mind is not too stupid to discern, that it is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God.

If the duelist is a mere creature of solitude, in whose life or death, happiness or misery, no human being is particularly interested; if no bosom will glow with his prosperity, or bleed with his sufferings; if no mourner will follow his hearse, and no eye drop a tear over his grave; still he is a man. As a man, he owes ten thousand duties to his fellow-men; and these are all commanded by his God. His labours, his example, his prayers, are daily due to the neighbour, the stranger, the poor, and the public. He cannot withdraw them without sin. The eternal Being, whose wisdom and justice have sanctioned all these claims, will exact the forfeiture at his hands; and enquire of the wicked and slothful servant, why, in open defiance of his known pleasure, he has thus shrunk from his duty, and buried his talent in the grave.

Is he a son? Who licensed him, in rebellion against the fifth command of the Decalogue, to pierce his parents’ hearts with agony, and to bring down their grey hairs with sorrow to the grave? Why did he not live, to honour his father and his mother; to obey, to comfort, to delight, and to support them in their declining years; and to give them a rich reward for all their toil, expense, and suffering, in his birth and education, by a dutiful, discreet, and amiable life, the only reward which they asked? Why did he shroud the morning of their happiness in midnight, and cause their rising hopes to set in blood? Why did he raise up before their anguished eyes the spectre of a son, slain in the enormous perpetration of sin; escaping from a troubled grave; or coming from the regions of departed spirits to haunt their course through declining life; to alarm their sleep, and chill their waking moments, with the despairing, agonizing cry,

“Death, ‘tis a melancholy day

To those that have no God.”

Is he a husband? He has broken the marriage vow; the oath of God. He has forsaken his wife of his youth. He has refused to furnish her sustenance; to share her joys; to sooth her sorrows; to watch her sick bed; and to provide for his children and hers, the means of living here, and the means of living for ever. He has denied the faith, and is worse than an infidel. Where, in that fatal, guilty moment, when he resolved to cast away his life, were his tenderness to the partner of his bosom; the yearnings of his bowels towards the offspring of his loins; his sense of duty; his remembrance of God? In every character, as a dependent creature, as a sinful man, his eternal life and death were suspended on his forgiveness of his enemies. He, who alone can forgive sins, and save sinners, has said, If ye forgive not men their trespasses, neither will your heavenly Father forgive you. He has gone farther. He has forbidden man even to ask pardon of God, unless with a forgiving spirit to his fellow-men. In vain can the duelist pretend to a forgiving temper. If he felt the spirit of the cross, could he possibly for an affront, an offence lighter than air, shed the blood of his neighbour? Could he plunge the friends of the sufferer into an abyss of anguish; sink his parents in irrecoverable despair; break on the wheel the hearts of his wife and children; and label on the door-posts of his house, Mourning, Lamentation, and Woe?

Satisfaction for a professed injury is the very demand which he makes; the only basis of his contest. Is this the language of forgiveness? It is an insult to common sense, it is an outrage on common decency, to hold this language, and yet profess this temper. The language is the language of revenge. The spirit is the spirit of revenge. The varnish, notwithstanding it is so laboriously spread, is too thin to conceal the gross materials, or to deceive the most careless eye. Revenge for a supposed affront, revenge for wounded pride, for disappointed ambition, for frustrated schemes of power, dictates the challenge, seizes the weapon of death, and goads the champion to the field. Revenge turns the heart to stone, directs the fatal aim, and gloomily smiles over the expiring victim. Remove this palliation, miserable as it is, and you make man a fiend. A fiend would murder without emotion; while man is hurried to the dreadful work by passion only.

But what an image is presented to the eye by a man, thus dreadfully executing revenge! A worm of the dust; a sinful worm, an apostate, who lives on mercy only; who would not thus have lived, had not his Saviour died for him; who is crimsoned with ten thousand crimes, committed against his God; who is soon to be tried, judged and rewarded for them all; this worm raises its crest, and talks loftily of the affront which it has received, of injured honour, of wounded character, of expiation by the blood of its fellow worm. All this is done under the all-searching eye, and in the tremendous presence, of Jehovah; who has hung the pardon of this miserable being on his forgiveness of his fellow. Be astonished, O Heavens, at this! And thou earth, be horribly afraid!

Nor is this crime merely an execution of revenge; it is a cold, deliberate revenge. The deliberate killing of a man is Murder, by the decision of common sense, by the decision of human laws, by the decision of God. How few murderers have an equal opportunity, or equal advantages, to deliberate! By a mind informed with knowledge, softened with the humanity of polished life, enlightened by revelation, conscious of a God, and acquainted with the Saviour of mankind, a cool, deliberate purpose is formed, cherished, and executed, of murdering a fellow-creature. The servant, who forgave not his fellow-servant his debt of an hundred pence but thrust him into prison, was delivered over to the tormenters by his Lord, until he should pay the ten thousand talents, which he owed, when he had nothing to pay? What will be the destiny of that servant, who, in the same circumstances, for a debt, an injury, of the tenth part of the value of an hundred pence, robs his fellow-servant of his life?

Had an Apostle, had Paul, amidst all the unexampled injuries which he suffered, sent a challenge, or fought a duel, what would have become of his character as an Apostle, or even as a good man? This single act would have destroyed his character, and ruined his mission. Infidels would have triumphantly objected this act, as unquestioned proof of his immorality, of his consequent unfitness to be an Apostle from God to mankind, and of his destitution, therefore, of inspiration. Nor could Christians have answered the objection. But can that conduct, which would have proved Paul to be a sinner, consist with a virtuous character in another man?

Had the Saviour of the world 2 (I make the unnatural supposition with shuddering, but I hope with becoming reverence for that great and glorious Person) sent a challenge, or fought a duel, would not this single spot have eclipsed the Sun of Righteousness forever? Can that spot, which would have sullied the divinity of the Redeemer, and obscured his mediation, fail to be an indelible stain, a hateful deformity, on those whom he came to save? If any man have not the spirit of Christ, he is none of his.

All these things reason, and humanity, and religion plead; yet how often, even in this infant country, this country boasting of its knowledge and virtue, they plead in vain! Duels in great numbers are fought; revenge is glutted; and the miserable victims of wrath and madness are hurried to an untimely end. Come then, thou surviving, and in thine own view, fortunate and glorious champion; accompany me to the scenes of calamity, which thou hast created, and survey the mischiefs of duelling.

Go with me to yonder church-yard. Whose is that newly opened grave? Approach, and read the letters on the yet uncovered coffin. If thou canst retain a steady eye, thou wilt perceive, that they denote a man, who yesterday beheld, and enjoyed, the light of the living. Then he shared in all the blessings and hopes of life. He possessed health, and competence, and comfort, and usefulness, and reputation. He was surrounded by neighbours who respected, and by friends who loved him. The wife of his youth found in him every joy, and the balm of every sorrow. The children of his bosom hung on his knees, to receive his embrace, and his blessing. In a thousand designs was he embarked, to provide for their support and education, and to settle them usefully and comfortably in the world. He inspired all their enjoyments; he lighted up all their hopes.

Yesterday he was himself a creature of hope, a probationer for immortality. The voice of mercy invited him to faith and repentance in the Lord Jesus Christ, to holiness, and to heaven. The day of grace shone, the smiles of forgiveness beamed upon his head. While this happy day lasted, God was reconcilable, his Redeemer might be found, and his soul might be saved. The night had not then come upon him, in which no man can work.

Where is he now? His body lies mouldering in that coffin. His soul has ascended to God, with all its sins upon its head, to be judged, and condemned to wretchedness, which knows no end. Thy hand has hurried him to the grave, to the judgment, and to damnation. He affronted thee; and this is the expiation which thy revenge exacted.

Turn now to the melancholy mansion, where, yesterday, his presence diffused tenderness, hope, and joy. Enter the door, reluctantly opening to receive even the most beloved guest. Here mark the affecting group assembled by this catastrophe. That venerable man, fixed in motionless sorrow, whose hoary head trembles with emotions unutterable, and whose eye refuses a tear to lessen his anguish, is the father who begat him. That matron wrung with agony, is the mother who bore him. Yesterday he was their delight, their consolation, the staff of their declining years. To him they looked, under God, to lighten the evils of their old age; to close their eyes on the bed of death; and to increase their transports throughout eternity.

But their comforts and their hopes have all vanished together. He is now a corpse, a tenant of the grave; cut off in the bloom of life, and sent unprepared to the judgment. To these immeasurable evils thou hast added the hopeless agony of remembering, while they live, that he was cut off in a gross and dreadful act of sin, and without even a momentary space of repentance: a remembrance, which will envenom life, and double the pangs of death.

Turn thine eyes, next, on that miserable form surrounded by a cluster of helpless and wretched children. See her eyes rolling with frenzy, and her frame quivering with terror. Thy hand has made her a widow, and her children orphans. At thee, though unseen, is directed that bewildered stare of agony. At thee she trembles; for thee she listens; lest the murderer of her husband should be now approaching to murder her children also.

She and they have lost their all. Thou hast robbed them of their support, their protector, their guide, their solace, their hope. In the rave all these blessings have been buried by thy hand. If his affront to thee demanded this terrible expiation, what, according to thine own decision, must be the sufferings, destined, to retribute the immeasurable injuries, which thou hast done to them?

The day of this retribution is approaching. The voice of thy brother’s blood crieth from the ground, and thou art now cursed from the earth, which hath opened her mouth to receive thy brother’s blood. A mark is set upon thee by thy God; not for safety, but for destruction. Disease, his avenging Angel, is preparing to hurry thee to the bed of death. With what agonies wilt thou there recall thy malice, thy revenge, and the murder of thy friend! With what ecstacy will thy soul cling to this world, and with what horror will it quake at the approach of eternity! Alone, naked, drenched in guilt, thou wilt ascend to God. From him what reception wilt thou meet From his voice what language wilt thou hear? “Depart, thou cursed into everlasting fire.” And lo! The melancholy world of sin and suffering unfolds to receive thee. Mark, in the entrance, the man, whom thou hast plundered of life, and happiness, and heaven, already waiting to pour on thy devoted head, for the infinite wrongs which thou hast done to him, the wrath and vengeance of eternity.

At the close of this awful survey, cast thine eyes once more around thee, and see thyself, and thy brother duellists, the examples, the patrons, and the sole causes, of all succeeding duelling. Were the existing advocates of this practice to cease from upholding it; were they to join their efforts to the common efforts of man, and hunt it out of the world; it would never return. On thee, therefore, and thy companions, the innumerable and immense evils of future duelling are justly charged. To you, a band of enemies to the peace and safety of man, a host of Jeroboams, who not only sin, but make Israel to sin through a thousand generations, will succeeding ages impute their guilt, and their sufferings. You efficacious and baleful example, will make thousands of childless parents, distracted widows, and desolate orphans after you are laid in the grave. You invite posterity to wrest the right of deciding private controversies out of the hands of public justice; and to make force and skill the only umpires between man and man. You entail perpetual contempt on the laws of man, and on the laws of God; kindle the flames of civil discord; and summon from his native abyss anarchy, the worst of fiends, to lay waste all the happiness, and all the hopes of mankind.

At the great and final day, your country will rise up in judgment against you, to accuse you as the destroyers of her peace, and the murderers of her children. Against you will rise up in judgment all the victims of your revenge, and all the wretched families, whom you have plunged in hopeless misery. The prowling Arab and the remorseless Savage, will there draw nigh, and whiten their crimes by a comparison with yours. They indeed were murderers, but they were never dignified with the name, nor blessed with the privileges of Christians. They were born in blood, and educated to slaughter. They were taught from their infancy, that to fight, and to kill, was lawful, honourable, and virtuous. You were born in the mansion of knowledge, humanity, and religion. At the moment of your birth, you were offered up to God, and baptized in the name of the Father, of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost. You were dandled on the knee, and educated in the school of piety. From the house of God you have gone to the field of blood, and from the foot of the cross, to the murder of your friends. You have cut off life in the blossom, and shortened, to the wretched objects of your wrath, the day of repentance and salvation. The beams of the Sun of righteousness, shining with life-giving influence on them, you have intercepted; the smile of mercy, the gleam of hope, the dawn of immortality, you have overcast forever. You have glutted the grave with untimely slaughter, and helped to people the world of perdition. Crimsoned with guilt, and drunk with blood, Nineveh will ascend from the tomb, triumph over your ruin, and smile to see her own eternal destiny more tolerable than yours.

Endnotes

1. This, however, is beyond a doubt the real state of the subject. Duellists profess to fight on equal terms, and make much parade of adjusting the combat so as to accord with these terms. But all this is mere profession. Most of those who design to become duellists, apply themselves with great assiduity to shooting with pistols at a mark placed at the utmost usual fighting distance. In this manner they prove that they intend to avail themselves of their superior skill, thus laboriously acquired, to decide the combat against their antagonists. It makes not the least difference, whether the advantage consists in better arms, a better position, an earlier fire, or a more skillful hand. In each case the advantage lies in the greater probability which it furnishes one of the combatants of success in the duel. Superior skill ensures this probability, and is, therefore, according to the professions of duellists, an unfair and iniquitous advantage.

2. It is, I believe, universally admitted by Christians, that the conduct, which would have been sinful in Christ, considered merely as placed under the law of God, and required to obey it, is sinful in every man acquainted with the Gospel; and that the conduct of Christ as a moral being, is in every instance applicable to our circumstances, a rule of duty to us. I have put this strong case, because I believe few of those, who may evade with various pretences the preceding arguments will be at a loss to determine here. In the same manner divines customarily make, on certain occasions, the supposition of injustice, falsehood, or other turpitude, and apply it to the divine character; to shew, forcibly, what deplorable consequences would follow, were the supposition true.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!