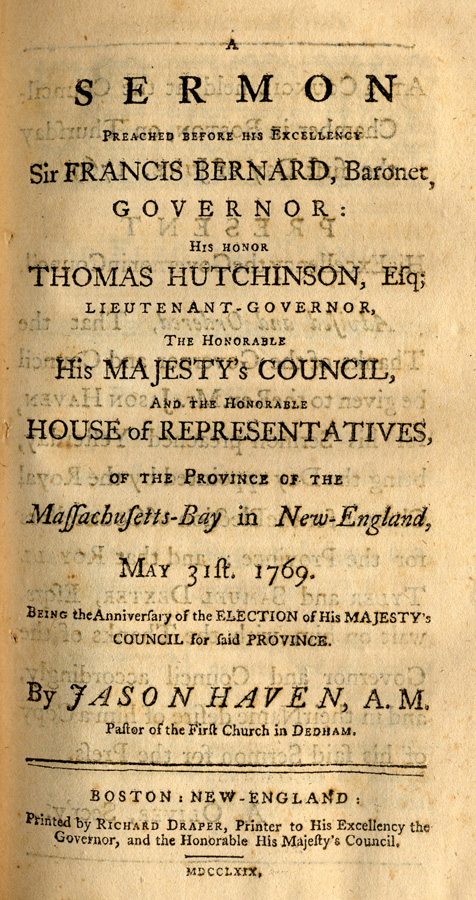

Jason Haven (1733-1803) preached this sermon in Massachusetts on May 31, 1769.

SERMON

PREACHED BEFORE HIS EXCELLENCY

SIR FRANCIS BERNARD, BARONET,

GOVERNOR:

HIS HONOR

THOMAS HUTCHINSON, Esq;

LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR,

THE HONORABLE

HIS MAJESTY’S COUNCIL,

AND THE HONORABLE

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES,

OF THE PROVINCE OF THE

MASSACHUSETTS BAY in NEW ENGLAND

MAY 31ST. 1769.

Being the Anniversary of the ELECTION of His MAJESTY’s COUNCIL for said PROVINCE.

BY JASON HAVEN, A.M.

Pastor of the First Church in DEDHAM.

Chamber in Boston, on Thursday

the first Day of June, 1769.

PRESENT

His Excellency the Governor in Council,

Advised and Ordered, That the Thanks of the Governor an council be given to the Rev. Mr. Jason Haven, for his Sermon preached Yesterday being the Day appointed by the Royal Charter for the Election of Councellors for the Province : and that ROYALL TYLER and SAMUEL DEXTER, Esqrs. wait on him with the Thanks of the Governor and Council accordingly, and in their Name desire of him a Copy of his said Sermon for the Press.

A. OLIVER, Secr’y.

Psalm LXXV. 6, 7.

For promotion cometh neither from the east, nor from the west, nor from the south: But God is the Judge; He putteth down one, and setteth up another.

By the light of reason and nature, we are led to believe in, and adore God, but not only as the maker, but also as the governor of all things. In the same way we may be satisfied that it is agreeable to the divine will, that civil government be established among men, on principles equitable in themselves, and conductive to the common good. But in these points, revelation comes in the assistance of reason, and shews them to us in a clearer light than we could see them without its aid. This is done by many passages of sacred scripture, and by that which I have now read in particular; which, without a critical examination of its connection, or any labored comment on it, may consider – God’s approbation of civil government – His agency in putting men into, and removing them from places of power – what views persons should have in seeking and accepting a part in government – what rules should be observed in introducing men into office – how those that are promoted should behave towards the people – and how the people should behave towards them. The two former of these heads of discourse lie plainly in the words of my text; the others are natural inferences from them.

The first thing to be considered is God’s approbation of civil government among mankind. This might be argued from the dispositions and capacities which he hath implanted in human nature. Buy these men are adapted to society, and inclined to associate together; and by associating, the happiness of each individual may be greatly improved.

By forming into civil society, men do indeed give up some of their natural rights; but it is in prospect of a rich compensation, in the better security of the rest, and in the enjoyment of several additional ones, that flow from the constitution of government, which they establish. Individuals agreeing in certain methods, in which their united force and strength shall be employed for mutual defense and security, is a general idea of civil government. These methods of defense being lawful in right in themselves, must be agreeable to the will of God “who loveth righteousness.” They must please him who is “a God of order and not of confusion;” as they tend to prevent “confusion and every evil work,” which otherwise would prevail, without restraint, among such imperfect creatures as we are.

The state of things in our world is evidently such, as to render civil government necessary. But for this, life liberty, and property would be exposed to fatal invasion. The lusts of men, from whence come wars and fightings, would not be under sufficient restraint. Their conduct would be like that complained of in Israel, when they had no king. “Everyone did that which was right in his own eyes. ” 1 Men would resemble the fishes in the sea, the greater devouring the less. This state of things as fully determines the will of God, who delights in the happiness of his creatures, in favor of civil government, as it could have been done by an express revelation. The voice of reason, in this case is the voice of God.

But the will of God, as to this thing, is not only deducible from these reasoning’s. His word of revelation declares it. “The powers that be are,” expressly said to be, “ordained of God.” Civil rulers are called “the ministers of God.” And “he that resisteth them” is said to “resist the ordinance of God.” 2

But though God’s approbation of civil government is so evident; yet he hath not seen fit to point out any particular form of it, in which all men are obliged to unite. This is left as a matter of free choice and agreement. Men have a natural right to determine for themselves, in what way, and by whom they will be governed. The notion of a divine indefeasible right to govern, vested in particular persons, or families, is wholly without foundation; and is I think as generally exploded at this day, by en of sober minds, as that of uninterrupted succession in ecclesiastical office, from the apostles of Christ, in order to the validity of Christian administrations.

“The most impartial disquisitions of this matter, faith an anonymous writer, founded on the common sense and practice of mankind, have long ago convinced the wise and unprejudiced, that no individual, however nobly born, has a right over the person or property of another, except only from mutual compact, entered into for general benefit; the conditions of which are as obligatory on the governing, as on the governed parties. No man, in the nature of things, is in anyway superior or inferior to his fellow citizens, but on such conditions, as they are supposed to have mutually consented to. It is only to prevent the confusion which riches, interest, or ambition might create among persons equally qualified, that the sovereignty hath been settled in particular families. It is in regard only to conveniency, that the succession should remain uninterrupted, as long as it can be consistent with the good of the whole. But where this is infringed, dispensed with superseded, the obligation is cancelled. The people are free, and may either choose a new form of government, or put their old, into other hands.”

All nations have not chosen the same form of government. Nor can we determine that anyone would be best for all. The different genius, temper and situation of nations and countries, may make different constitutions of civil policy eligible, as different temperaments in human bodies, and the different climates in which they are placed, require different methods of regimen.

The Theocracy of the Jews doth not disprove this natural liberty of choice. That people, while it continued; and it was ungrateful in them to be so soon weary of it. Other nations were left to their liberty, to choose such a form of government, as they might think would best answer the end of all government, the public welfare; whether that of Monarchy, Aristocracy, or Democracy; or a mixture of these. It is a mixture of these that our nation fixed upon. And this we are ready to think the happiest that can be. We may possibly be prejudiced in favor of it, because it is our own. Indeed we have less reason to think we are since we have so many testimonies of strangers to its excellency. Besides these testimonies, we have had such proofs of its goodness, as are most convictive, those of experience. By it “we have enjoyed great quietness, and important favors have been done to our nation.”

In this form of government, power and privilege are happily united. They are wrought into its foundation, so that they cannot be separated, but by pulling down the pillars of it. Magistrates cannot exercise their power of magistrates. We have reason to be thankful to the great Founder of civil government, that under his influence, our nation hath agreed in this constitution, which hath already contributed so much to its happiness; and the important blessings of which, we hope, will flow down to the latest posterity.

Indeed the best form of government will not render a people safe and happy, without a good administration. More depends on places of public trust being properly filled, than on the constitution. A people may perhaps, for a season be tolerably happy under the most exceptionable form of government;’ but can scarcely be so, under the best, when administration is grossly corrupt. Their rights and privileges are very nearly affected by the character and conduct of their rulers. The advancement of persons to places in government is therefore a most interesting affair. It requires the serious attention of all, who have a hand in it : And it will lead every man of religion, to implore the favor and influence of the supreme ruler, who putteth down one, and setteth up another.

This leads me,

SECONDLY. To consider the agency of God, in putting men into, and removing them from places in government.

PROMOTION, faith the penman of my text, cometh neither from the east nor from the west, nor from the south. We cannot (as one remarks on the words) “gain it either by the wisdom of the men of the east or by the numerous forces of the western isles; or from those of Egypt or Arabia, which lie southward of Judea. The reason why the north is not mentioned may be because the same word which is rendered north signifies God’s secret place or counsel, from whence promotion doth come.” Perhaps no more is intended by this poetical expression, than that the most favorable concurrence of second causes, will not prevail to advance persons in government, without the influence of the first. A truth which none can disbelieve, who admit God’s superintendencey over all human affairs. A truth, in the faith of which our own observation may have been sufficient to confirm us. Have we not known some ready to compass sea and land, and to go from east to west, and from north to south, in pursuit of honor? And yet have they not found it like a shadow, in this respect, as well as in some other, that it hath fled before them with a motion as swift as that with which they have followed it? While they have tried every promising method to climb the slippery hill of honor, all their attempts have been blasted, and blasted in such secret and unexpected ways, as could not be accounted for but by the agency of him “who disappoointeth the devices of the crafty, so that their hands cannot perform their enterprise. 3

Promotion being denied to the power of second causes, is attributed to that of the first. God is the judge: He putteth down one, and setteth up another.

God is the judge – When several parties contend for the prize of the preferment he determineth it to which he pleaseth so as best to serve his own purposes it is not only safe but happy for the world, that absolute and uncontrollable power should be possessed by a being of infinite wisdom, invariable justice and boundless mercy. Such power is often ascribed to God, in the inspired writings. “Wisdom and might are his : He removeth kings, and setteth up kings : He hath put down the mighty from their seats, and exalted them of low degree. The most nigh ruleth in the kingdom of men, and giveth it to whomever he will.” 4

God is the judge of men’s qualifications for government and his “judgment is always according to truth.” He knows whom to promote and whom to depose, in order to answer the wise plan of his universal providence. This power God doth not usually exercise in an immediate way, but by the intervention of several second causes; and these are united and combined together in such a manner, as could be done by no understanding but one that is infinite. Scared, and other histories furnish us with instances hereof. The advancement of Joseph to great dignity and power in the Egyptian court, is a remarkable one. A variety of unconnected cause operated to bring this about unconnected in themselves, but united by him, “whose kingdom ruleth over all.” It was by the agency of God, that king Saul was disgraced, and David advanced; an event, to which it is probable, our text has special reference. By this it came to pass that proud Haman was hanged on the gallows he had made, of fifty cubits high; while Mordecai the Jew, for whom he had prepared the same, was promoted. By this, that haughty Nebuchadnezzar was turned a grazing among the beasts, to teach him that “the heavens do rule.” By this, that boasting Herod was eaten of worms, because he did not consider the he was one himself.

The influence of the supreme governor of the world, in bringing about such events, in later ages, is not less real, though perhaps less evident and immediate. It must be acknowledged in putting down some, and setting up others, in our own nation and land. The fall of that unhappy and misguided king, Charles the first, was an instance of it. So was that ever memorable event, so happy in its consequences to Great Britain, and to these Colonies, called the Revolution, when king James the second abdicated the throne, and King William and Queen Mary, of glorious memory, were advanced to it; which made way for the present happy establishment in the house of Hanover. The people of this province, not only shared in common with their fellow subjects, on the other side of the Atlantic, in the advantages arising from this great change in government, but were particularly happy, in being delivered from the oppressive and tyrannical administration of Sir Edmund Andros. The agency of heaven in these events, doth not determine the innocence or guilt of those, who were the voluntary instruments of bringing them about. “Thou couldest have no power at all against me,” said our Savior to Pilate, “except it were given thee from above.” 5 Yet this did not prove him innocent, in “condemning that just one.”

The promotion of men to places of power and trust, who either have no talents for government, or are disposed to use those that they have, to wicked purposes, is an event, which may seem hard to be accounted for. “God’s judgments are a great deep.” This however must be a settled principle with us, “that the Judge of all the earth doth right.” His providence is by no means to be impeached. The moral evils which take place, in consequence of such promotions, are not to be charged on him. He may permit such things to punish a bad temper, either in the persons promoted, or in the people over whom they are set or in both. We should consider it as the primary design of such punishment to reform them; but if they remain incorrigible under it, a fuller display of God’s rectoral justice and hatred of sin, will be made in their ruin. “The scripture faith unto Pharaoh, even for this same purpose have I raised thee up, that I might shew my power in thee, and that my name might be declared throughout all the earth. ” 6 In judgment to Israel, Saul, and several wicked kings, were set over them. “There is (says Doctor Tillotson) a kind of moral connection and communication of evil and guilt, between princes and people; so that they are many times mutually rewarded for the virtues and good actions, and punished for the sins and faults, of one another.”

Good men, who have excellent talents for governments, and disposition to use them for the public advantage, are sometimes kept out of place, or suddenly stripped of that civil power with which they had been clothed. This is a chapter in the book of providence hard to be explained. In this way, we have reason to think, God sometimes designs to punish a people’s ingratitude to him for a good administration, which they have enjoyed; their unsubmissiveness to it, and abuse of its blessings. He may also intend the advantage of the persons thus displaced, by a dispensation generally grievous enough to them. He may behold their virtue endangered by their elevation. He may foresee that they would not be proof against the temptations of it; and that they would neglect, what to them, as well as to others is “the one thing needful.” The care of their souls. Many have lost ground in religion by advancement, and recovered it by a return to private life.

Having remarked on the agency of God in advancing and deposing men, I go on.

Thirdly, to consider what views they should have in seeking and accepting places in government. I here mention seeking places, for I do not imagine that all kinds and degrees of this, are to be condemned; though the character of seekers, in general, is a very odious and individious one. Importunity in a candidate for promotion is a presumptive evidence, that he is unfit for it. Me on the best qualifications have generally disdained those low arts and intrigues, by which some have made their way into places of power. It is hard to say what can be more base and wicked than the conduct of those, who attempt to rise by the help of adulation and bribes, unless it be that of those who hearken to them, and become the tools of their pride and ambition. That temper, however, deserves to be denominated a false modesty, which makes men always decline preferment, when it comes in their way; or avoid those offices which require great abilities, when they know themselves to be possest of them. Hereby they may be chargeable with hiding talents which they ought to improve for the public good.

But all men’s endeavors to rise in government should be such, as they have reason to think God approves; such as they can with sincerity recommend to his blessing, and wait on him to succeed. If this is not the case, they are in effect fighting against God. They ought not to seek, nor even to accept such offices as they know they cannot discharge, in a good measure answerable to the nature and importance of them.

God is the judge – You should be able to look up to him in confidence, that he approves every step you take in the way to posts of honor; and with a willingness to be disappointed, if in his unerring wisdom he sees you to be unfit for them; and that your success would operate either to the damage of the public, or of yourselves. Such a serious regard to God as the fountain of all power would shame men of virtue and modesty, out of those base methods, by which, it is to be feared, some are seeking after promotion.

Men indeed are generally partial to themselves. They think their accomplishments greater than they are. Under the influence of this partiality, some may with honest simplicity solicit, and enter into, such departments in government as they can by no means fill with dignity, and to the satisfaction of the public. This evil is to be guarded against by those, whose part it is to introduce men into office.

The rules to be observed by such is the

Fourth thing to be considered. The should act with great fidelity and caution is necessary, both in superior magistrates, in their appointments, and in the people, who choose persons into office. The business is of a very interesting nature; in doing it they should consider themselves as instruments in the hand of God, and therefore bound to consult his will, and to govern themselves by it. This teaches them to promote men according to their apparent merit; and not to be influenced by private connections, and prospects of personal advantage. The public prosperity greatly depends on your faithful discharge of your duty in this respect. You are accountable to God for the manner in which you discharge it. You are bound as you will answer it to him, to consider the qualifications of candidates, for places in government and to promote such and such only as you think in some good measure possessed of them.

What these qualifications are, I have not time particularly to consider. Tow of the most essential, and in which most others may be included, I shall briefly mention – Wisdom and Religion

No small degree of wisdom and knowledge is necessary to constitute a good ruler, whether he fills a place in the legislative, or executive part of government Solomon when advanced to be king over Israel, prayed for a wife and understanding heart. God approved his petition as seasonable, and gave a gracious answer to it. Wisdom is not only necessary for kings, and for persons in the highest seats of government, but proportionable degrees of it, for those who hold subordinate places. Rulers are compared to light, which, by a familiar metaphor, signifies knowledge. “The heads of the tribes of Issachar,” chosen to represent their brethren on a certain important occasion, are expressly said to be “men, that had understanding of the times, to know what Israel ought to do.” 7

Government is by no means safe in the hands of weak and ignorant men, how good soever their intentions may be. When such men have the management of our public affairs what can we expect, but that they run into confusion and disorder?

Nor is it every kind of knowledge that will qualify a man to govern. He must be acquainted with men, as well as things; otherwise he will be in continual danger of being imposed on, by the subtlety and address of designing men around him. He will confide in those who are not to be trusted and make those his counselors, who will take pains to lead him astray. It is the character of the supreme ruler, that, “He is a God of knowledge, by whom actions are weighed.” 8 Rulers among men, should have skill to form a due estimate of the actions of persons, under all that coloring which they lay on them. If they have not, how can they approve and reward those that have salutary influence on the public? How can they disapprove and counteract those of a contrary nature.

Rulers should not only be acquainted with the natural rights of the people, which are the same under every form of government, but also with those which originate from the constitution of the country where they live; that they may be tender of both, and able to defend both. They should know how to state the bounds of their own authority, and of the rights of the people; that while with firmness they assert the former, they may not infringe on the latter. Wisdom is necessary direct them in all that variety of business, to which their stations call them; which variety cannot now further consider.

Religion is the other qualification which I mentioned, as necessary to the character of a good ruler. He must be a man of religion, who discharges the duties of a magistrate with fidelity. By a man of religion, I mean once that is a true fearer of God, on that is in a good measure sanctified by his grace, formed to the temper recommended by the Gospel of Christ, and sincerely endeavors to act up to those rules of piety and virtue, which are therein prescribed.

Piety towards God is the only basis, on which a proper conduct towards men, can stand firm and steady against those blasts of temptation, to which all men are exposed; and which beat on those that are in elevated stations, with peculiar violence, as storms do on a house that stands on an eminence. “He that fears not God, will not regard man,” will not regard him with that tender concern for his prosperity, and that sincere endeavor to promote it, which the laws of religion require. True patriotism (for such a thing no doubt there is, though many may be strangers to it, who are fond of the name) hath its foundation in religion. A vicious man hath no settled principle of action. He is ruled by selfish passions to gratify these, he will sacrifice his conscience; he will trample on law, when he can do it with impunity; he will betray his friends; he will fell his country; having first “sold himself to work” all the kinds of “wickedness.”

Directly the reverse of this, is the tendency of religion, when it is pure and undefiled. It regulates the passions; it enlarges the mind; it fills it with noble and benevolent designs; it leads men to enterprise great things for the public good; it drives away the mists of prejudice and temptation, which are so apt to obscure the path of duty; it inspires a noble fortitude and resolution to pursue the end of government, though it should lead through a scene of painful opposition; though the best intentions should be misconstrued, and the most important services go unrewarded.

Now those that are concerned in promoting men to publish stations, are bound to have great regard to their virtue and religion. “For the God of Israel said the Rock of Israel spake to me – He that ruleth over men must be just, ruling in the fear of God.” 9 King David determined to act on this principle in calling men to office under him. “Mine eyes shall be upon the faithful in the land : He that walketh in a perfect way he shall serve me.” 10

God who is the judge, and who never errs inn judgment, hath plainly intimated the necessity of the tow leading qualifications for rulers, which I have mentioned – and not barely mentioned, but a little enlarged upon, as this head of discourse hath a particular aspect on the public transactions of this day. and are you not under the most solemn obligations to rega5rd the will of God in the promoting men? When you do so, you are workers together with him in the matter. When you do not, you set yourselves in opposition to him; and if he suffers you to succeed it will no doubt be in judgment to you, and to the land.

Fifthly. This subject instructs those who are advanced to places of power and trust, how they should have and presses fidelity on them by most serious motives. They are to consider themselves as promoted by God, and accountable to him for their conduct in public life. God is the judge: He putteth down one, and setteth up another.

Rulers ought always to look on their authority as derived to them. They are not originally possessed of any. This consideration should make them humble. I6t should give a check to a proud and haughty spirit; if, at any time, they find such an one ready to prevail. It should guard them against an overbearing tyrannical behavior. They should frequently make the reflection of the apostle; What have we that we did not receive? And if we received it, why do we boast?

They should consider their authority also as limited by the author of it; and that, both as to degree and continuance. God putteth down, as well as ariseth up. The triumphing of wicked rulers, who abuse their power in ways of pride and oppression, is generally short. To one of this character, the remark of the ancient sage concerning a hypocrite may be applied; “Though this excellency mount up to the heavens, and his head reach unto the clouds, yet he shall perish forever. – They that have seen him shall say where is he”? 11 When a virtuous people are oppressed, they may carry their complaints to God, in humble confidence, that he will not long “suffer the rod of the wicked to rest on the lot of the righteous.” 12

The consideration that their promotion cometh from God, should make rulers careful to improve it in a way, the most agreeable to his will, that they can. They do this, when they faithfully pursue the ends of government; when they studiously intimate the supreme ruler of the universe, “the scepter of whose kingdom is a right scepter.” Legislators do this, when they are solicitous that all the laws they enact, be just and good, correspondent to those of the supreme law giver. And those that execute the laws, when they act in their offices with steadiness and impartiality, that they may be a terror to evil-doers, and a praise to them that do well. All those who are vested with authority do this, when they have a tender concern for the rights and privileges of the people, and endeavor to preserve them entire and inviolate when they feel for them under all their burdens; and “in all their afflictions are afflicted” – when they construe their conduct into the most favorable sense it will bear – when they are ready to pass by, and excuse as many faults and offences, as will consist with the regular support of government – when they are willing to lose something of the severity of the magistrate, in the tenderness of a father – In a word, when in their administration, “mercy and truth meet together, righteousness and peace Kiss each other.” 13

Rulers should use their influence in an especial manner to promote religion. This they should do, not only by rewarding virtue, and punishing vice; but by what is often more influential their own pious and good example. People in the lower classes in life, have a peculiar fondness to imitate those that are in stations of eminence and dignity. This would operate for the general good, were “great men always wise,” virtuous, and circumspect, in their conversation. The morals of a people are greatly affected by those of their rulers. Religion flourished or declined in Israel very much according to the disposition and practice of their kings. Solomon observed that “if a ruler hearken to lies, all his servants are wicked.” 14 Vices receive a currency from the example of princes, as money doth, from their image and superscription. If magistrates are eminently pious and good, they are lights in the world, which shining before others induce them to “glorify our Father who is in heaven,” by a correspondent practice of piety and goodness. But if they are vicious they are like baleful sonnets, that spread plagues and desolations throughout a land, by their malignant influences.

God is the judge, says our text. Rulers should always consider him in that character. To him they are accountable for their conduct. I say not indeed that they are not, in some sense, accountable to men. The power of government is by God, the original source of it, logged in the people. By them it is delegated, under divine providence, to certain of their brethren, to be improved for the common good. When therefore they prostitute it to oppress and enslave, in direct contradiction to the ends of government; the people have a right to call them to account, and to take out of their hands the power which they have so abused.

But they are especially to consider themselves as accountable to God. They should remember that he now acts the part of a judge, so far as by his impartial eye to survey all their counsels, designs and actions. They should consider him as always present with them; and that their most secret purposes and schemes, are “naked and open to the eyes of him, with whom they have to do” 15; whose “eyes are as a flame of fire ” 16; and that this “righteous Lord loveth righteousness, and his countenance approveth the upright.” 17

A solemn sense of God in this tremendous character, cultivated in the minds of rulers, would banish a thousand temptations to venality and corruption. It would lead them to a humble review of their past behavior, that the errors of it may be repented of, and similar ones avoided, for time to come. It would make them afraid to indulge to any selfish and sinister designs, which militate against the public welfare, though they were sure to conceal them from the eye of men. The fear of God would check the fear of man, and prevent its prevailing on them so as to ensnare them. They would not fear losing their places, by faithfulness in discharging the duties of them. The would consider, it is the favor of God that makes their mountain stand strong; that their times are in his hands; the date of their political, as well as natural life.

Rulers should look forward to that approaching day, when they must appear before God’s august tribunal, and give account of all the talents he hath committed to them. The should endeavor to bring that day near in their meditations. It is apt to appear more distant than it really is, and so lessens to the eye of the mind, as objects to by their distance that of the body, The word of revelation assures us, that “it is appointed for all once to die, and that after death is the judgment; 18 and that “ever one shall give account of himself to God, ” 19 who is no respecter of persons; but will render to every one according to which God will proceed in the judgment, “that unto whomever much is given, of him shall much be required.” 20 Rulers have much committed to them; unfaithfulness in the use of it, will render their guilt very great, and their doom very dreadful. If they are now conscious of being habitually and allowedly unfaithful, they may well tremble, as a wicked governor once did, upon hearing of a judgment to come.

But a prospect happily different from this – a prospect as bright and glorious as this is dark and gloomy, opens upon that ruler, who cultivates in his heart the principles of undissembled piety and virtue, and forms his conduct upon them; whose governing aim is to comply with the will of God in all things, and to secure his approbation. He can look forward to that important day, in which God will judge the secrets of men by Jesus Christ, with calmness and comfort. He then shall receive the plaudit of his Judge, before assembled worlds of angels and men — “Well done good and faithful servant; thou hast been faithful in a few things; I will make thee ruler over many things; enter thou into the joy of thy Lord!” 21

FINALLY. Our subject suggests the duty of a people to their rulers. Rulers and subjects are correlate terms; they cannot subsist separately. If God sets some in the place of rulers, and invests them with a power to govern; He certainly appoints others to the place of subjects, and makes in their duty to submit to government. People are bound to regard the will and agency of God in clothing persons with civil authority. When they do so, they will obey “not only for wrath, but also for conscience sake;” 22 and treat them according to the nature and design of their offices, and their fidelity in the discharge of them.

It is incumbent on a people cheerfully to support civil government. This is not to be view as the part of charity and generosity, but of justice. The support of those, who employ their time and talents to serve the public, should be made easy and honorable. Those who diligently attend to the duties of their stations, have care, labor and anxiety enough. People should not increase these, by withholding from them an adequate reward for their services. This would tend to dishearten them, and to weaken their efforts for the public good.

A respectful treatment of their rulers is also the duty of a people, it is an apostolical injunction, that we “render honor to whom honor is due.” 23 It is due to those, who are raised to important seats of government. We should pray for them. We should treat their persons with veneration and esteem. We should speak of them, and to them, in decent and respectful language. To act contrary to this, is to weaken the springs of government, and to encourage those to speak evil of dignities,” who are already too much inclined to do it. “It is written thou shalt not speak evil of the ruler of thy people.” 24

A People are in duty bound to submit to their political fathers, in everything lawful. If they refuse this, they frustrate the design of God and men, in clothing them with this character and government is at an end. Submission is enjoined on a people, by several of the inspired writers. The passages in which it is so, have been often quoted, on occasions similar to the present, and are I trust too well known to need repeating at large. 25 They have by some been made to prove too much. They are no doubt to be understood with some limitation. “He is the minister of God to thee for good,” says St. Paul, of the civil magistrate. This implies, that so far as he pursues the end for which God placed him in office, he is to be obeyed. Nor should small instances in which we imagine he fails of this, be looked upon sufficient ground for refusing submission. These may arise rather from human frailty, than any settled disposition in him to abuse his power. But when he uses his authority for purposes just the reverse of those for which it was delegated to him – when he evidently encroaches on the natural and constitutional rights of the subject – when he tramples on those laws which were made, at once to limit his power, and defend the people – in such cases they are not obliged to obey him. They are guilty of impiety against god; and of injustice to themselves, and the community, of which they are members, if they do : For his commands interfere with those of the supreme ruler, and overthrow the foundations of government, which he hath laid. “We must obey God rather than man.” 26

The doctrine of passive obedience and non-resistance, which had so many advocates in our nation, a century ago is at this day, generally given up, as indefensible, and voted unreasonable and absurd. The unreasonableness and absurdity of it, hath indeed been proved by some of the greatest reasons of our age.

“Wheresoever law ends” (says the great Mr. Locke) “tyranny begins if the law be transgressed to another’s harm. And whoever in authority exceeds the power given him by law, and makes use of the force he hath under his command, to compass that upon the subject, which the law allows not, ceases in that to be a magistrate; and, acting without authority, may be opposed as any other man, who invades the right of another” – “Here, ‘tis likely, (continues he) the common question will be made, who shall be judge, whether the prince or legislature act contrary to their trust? This, perhaps, ill-affected and factious men may spread among the people, when the prince only makes use of his just prerogative. To this I reply : The people shall be judge; for who shall be judge whether his trustee or deputy acts well, and according to the trust reposed in him, but he who deputes him, and must by having deputed him, have still a power to discard him, when he fails in his trust? If this be reasonable in particular cases of private men, why should it be otherwise in that of the greatest moment, where the welfare of millions is concerned; and also where the evil, if not prevented, is greater, and the redress very difficult, dear and dangerous?”

There may indeed be danger that ill-disposed men – men disaffected to government in general, will “use this liberty,” which the God of nature hath given us, “for an occasion to the flesh,” to gratify the disorderly lusts of it; and so to disturb the peace of the society, of which they are members. Bu this is not a sufficient reason why we should discontinue our claim to it.

Subjects will, however, find it to their advantages to suffer great inconveniences, rather than to rise up against men in authority. They are not to expect an administration without faults. Small faults should not be remarked on with bitterness, or magnified with all the power of invention. This would increase the burden of government, already heavy enough on those, who are faithful in discharging the duties of it; and tend to discourage those from taking a part in it, who are best qualified. A generous readiness to make very kind allowance for what may be amiss in others, is perhaps one of the rarest qualities in the world. It is however a very necessary one, in the several connections of society, and particularly in that between rulers and people.

If anything hath been suggested in this discourse, which may serve to lead rulers, or people, in to a better understanding of their duty, and to animate them to diligence and fidelity in discharging it, the design of our assembling in this house of worship is not lost. I will suppose you possessed of every instructive sentiment that hath been suggested, if any such there hath been, and therefore shall not make a recapitulation of what hath been said, in the way of particular address.

Inattention to the duties of their stations is inexcusable in all orders of men. It becomes criminal and dangerous, in proportion to the importance of these duties. The public welfare greatly depends on the fidelity and vigilance of civil rulers.

It is I hope with sincere gratitude to god, that we see this anniversary. The public transactions of it, Honored Fathers, we look upon to be very interesting to this people. We have been seeking to the fountain of wisdom, for guidance and direction to be afforded to you, in them. To day you exercise an important privilege of our happy constitution, that of choosing Gentlemen to sit at the Council board; who are not only to constitute one branch of the legislature, but “to the best of their judgment, at all times, freely to give their advice to the Governor, for the good management of the public affairs of this government.” This is a privilege on which the happiness of this people not a little depends. It was always dear to our fathers, and is so to us. By it we have the great satisfaction of seeing the Council consist of men from among ourselves, whose interest is the fame with that of the people; and who are under all conceivable obligations to seek their welfare. This is a privilege secured to us by royal charter; on which security, I trust, under God, we may depend, for the continuance of it down to the latest posterity. A privilege which we have not forfeited; and God forbid we should, in any furniture time, be guilty of such conduct, as might render it just to deprive us of it.

What we enjoy by charter, is not to be looked upon barely as matter of grace; but, in a measure at least, of right. Our fathers faithfully performed the conditions, on which charter privileges were grated. To do this they passed through a scene of hardships labors and sufferings. These were productive of great advantages to the mother country. Our charter privileges are those of Englishmen; those of the British constitution; as our form of government, in this province, is an image in a miniature of that of our nation.

The appointment of the Governor, and commander in chief, is by the province charter, which we wish never to see vacated, reserved to the crown, In this we acquiesce. We indeed consider it as preferable to annual elections by the people.

Both the other branches of the legislature, we have the liberty of choosing. We hope the good people f this province have acted, with due consideration, in the choice they have made of persons to represent them, in the present assembly; and that all who are to be concerned in the elections of this day, will be influenced by motives, truly religious and patriotic. It is not wealth 27 — it is not family — it is not either of these alone, nor both of them together, tho’ I readily allow neither is to be disregarded, that will qualify men for important seats in government, unless they are rich and honorable in other and more important respects. This providence hath had men and such I doubt not there are still among us, in whom all these qualities are happily united. But in the first place, and before all other things, you should regard wisdom and integrity, understanding and religion, as qualifications for the business of government. If you aim to choose men thus qualified, you are “workers together with God,” who is the fountain of all promotion. If you give your suffrages for those, whom you know to be of a contrary character, you are chargeable with nothing less than a voluntary opposition to the will of heaven. A serious thought with which we wish to have our minds deeply impressed. It is always important to have wise and faithful rulers. It is peculiarly so, when the state of a people is difficult and perplexed. None can doubt ours being such, at the present day. All must agree in this, however different their sentiments may be, as to the immediate occasions of our troubles. Mutual confidence and affection, between Great Britain and these Colonies, I speak it with grief seems to be in some measure lost. I trust nothing of our loyalty to the best of Kings, or of our readiness to yield obedience to the due exercise of the authority of the British Parliament, is lost. People indeed generally apprehend some of their most important civil rights and privileges to be in great danger; and that several of them cannot be enjoyed under the execution of certain acts, lately passed in the Parliament of Great Britain, how far these apprehensions are just, is not my province to determine. Nor shall I pretend fully to point out the political causes of our unhappiness; or these steps which are necessary to be taken, for the redress of our grievances.

This matter more immediately belongeth to you, our honored Fathers. If we suffer by being misrepresented to our most gracious Sovereign, or to his ministry, ‘tis your part to remove the hurtful influence hereof, in such ways, as you shall think most proper and decent. ‘Tis your’s, to plead their cause, with “right words,” which “are forceable,” and “words of truth” which must, which will prevail.

The Ministers of religion will unite their endeavors, to investigate and declare the moral cause of our troubles. We should endeavor, my reverend Fathers and Brethren, and I trust we have been endeavoring, to direct the eye of our people to the hand of God, in the evils which are come upon us, and which threaten us. “Is there any evil in the city, and the Lord hath not done it?” 28 Are not these calamities to be viewed as tokens of the divine displeasure against us, on account of our sins? Is it not a day in which we ought to “cry aloud and not spare, to shew our people their transgressions and their sins?” 29 Should we not most importunately call them to repentance and reformation, as the only way in which we can expect the removal of our difficulties? It hath probably been the fault of this people, in these days of darkness and doubtful expectation, that they have fixed their thoughts too much on second causes, with our duly regarding the first – that they have been too ready to censure the conduct of others, without making proper reflections on their own. Hath not God reason to complain of us, as he did of Israel, in a day of calamity; “I hearkened and heard, but they spake not aright. No man repented him of his wickedness, saying what have I done?” 30

The prospect at this day is indeed dark: The darkest part of it arises from the decay of religion, and the prevalence of wickedness among us. Is it not too evident to be denied, that “inquiry greatly abounds,” and that “the love of many” to God and religion, “is waxen cold?” Must we not own that by our sins, we have forfeited all our privileges, into the hands of God; though I trust not, into the hands of men? And are not many of the evils we suffer, the natural and necessary, as well as moral effects of our vices? Is it possible a people should be happy, when pride, and extravagance, luxury, and intemperance abound among them? Will not poverty and disease, uneasiness and contention naturally spring from these vices? Doth not the providence of God loudly call on all orders of men, to unite their most vigorous endeavors, to check the growth of the sins which I have mentioned, and of others which might be named; such as the profanation of God’s name, 31 and day; uncleanness; and acts of violence, injustice, and oppression. We confide in the wisdom and fidelity of our rulers, to make and execute good and wholesome laws for the suppression of these vices; and for the encouragement of industry, frugality, and temperance, and all those virtues which constitute and adorn the Christian character; and to add life and energy to law, by their own good example. And I hope we shall all, in our several stations, most heartily abet the important design. Our temporal salvation, under God, depends upon it. a virtuous people will always be free and happy.

“Righteousness exalteth a nation.” Could we see people in general humbling themselves under the mighty hand of God, in the evils that are come upon us – could we see a general disposition in them, to break off from their sins by righteousness, and from their iniquities by turning to the Lord – could we see practical piety and religion prevailing among all ranks of men – how much would the prospect brighten up? God would appear for us, “who is the hope of his people, and the savior thereof in the day of trouble. ” 32 And “if God be for us, who can be against us? ” 33 He can work deliverance for us in a thousand ways to us unknown. Then our peace shall be as a river, when our righteousness is as the waves of the sea. Mutual harmony and affection shall be restored between Great Britain and her colonies, and between all orders of men in them. The burdens under which we groan shall be removed. We shall no longer be so unhappy, as to be suspected of wanting loyalty to our King, or of having the least disposition to refuse a constitutional subjection to our parent country. The great evils which we now suffer, in consequence of such groundless suspicions, shall be removed. We shall sit quietly enjoying the fruit of our fathers unremitting labors, and of our own, and have none to make us afraid. We shall behold our settlements extending themselves into the yet uncultivated lands. “The wilderness shall become a fruitful field and the desert shall blossom as the rose.” Our navigation shall be freed from its present embarrassment; and trade recover a flourishing state. Our rights and privileges shall be established on a firmer basis than ever. Every revolving year shall add something to the glory and happiness of America. And those that behold it shall see occasion to say, “Happy art thou O people! Who is like unto thee, saved of the Lord! The shield of thy help, and who is the sword of thine excellency!” 34

Whose breast doth not burn with desires to see his dear native land in such a state, the happy reverse of it’s present one! Who would not be ambitious of contributing something towards it! This we have all power to do. Let us up, and be doing and the Lord shall be with us.

But Christianity, my respectable hearers, which we profess, carries our thoughts beyond this present state of things. This life is but the preface of our existence. Affairs will never be in so happy a situation in it, as we could wish for. It is not agreeable to God’s universal plan of government, that we should here be free from every pricking brier and grieving thorn. We are too apt to lay our account for refined happiness in this life. Frequent disappointments are necessary to teach us our error, and to wean us from the vanities of time and sense. This is the salutary effect of our troubles; and when we find it in ourselves, we should acknowledge the kindness of heaven in permitting them.

A few days will close the present scene with us all. We must quit our stations, be they higher or lower. We must bid adieu to this world, and enter into the eternal one. There an endless circle of happiness, infinitely greater than can be derived from the most prosperous state of things here, is provided – provided by the mercy of God, through the mediation of Christ – provided for all, who repent and believe the gospel – for all, who act their part well on the stage of the present life – who serve God and their generation faithfully, according to his will.

Be this the object of our principal hopes, and desires! Let us continue patient in the ways of well doing; seeking for glory, honor and immortality; till, through the riches of God’s grace in Christ, we be crowned with eternal life.

Endnotes

4. Dan. II. 21. Luke I. 52. Dan. IV.

27. When L. Quintius Cincinnatus was created Dictator, riches were not by the generality of the Roman citizens thought necessary to preferment. His estate was a farm consisting only of four acres of land. He was at plough when the deputies came to him from the Senate, to acquaint him of his promotion. Wherever wisdom and virtue were found in a person, though destitute of a fortune, he stood fair to be advanced. And yet there were a few among the Romans even in that day, as there is a greater number among us in this, who are well described by Livy, when he says — “Operæ pre4tium est udire, qui omina præ divitiis humana spernunt; neque honori magno locum, neque viruti putant esse, nisi essuse affluent opes.

31. If God’s holy name is, at this day, too frequently and sometimes irreverently invoked, even in a judicial manner, every sincere friend to virtue and religion must wish to have this practice, so affrontive to the deity, and so destructive to the morals of the people, discontinued.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!