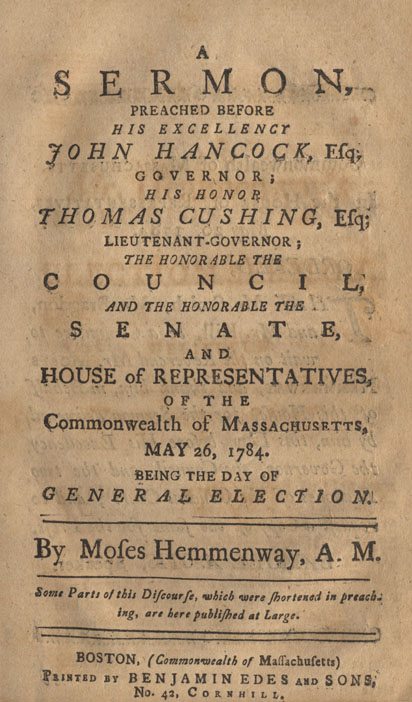

Moses Hemmenway (1735-1811) graduated from Harvard in 1755, a classmate of John Adams. He preached at Lancaster, Boston, Townsend, Wrentham, and New Ipswich after graduating college; then settled as pastor of Wells (1759-1810). This sermon was preached by Hemmenway on May 26, 1784 in Massachusetts.

SERMON,

PREACHED BEFORE

HIS EXCELLENCY

JOHN HANCOCK, Esq.

GOVERNOR;

HIS HONOR

THOMAS CUSHING, Esq;

LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOR;

THE HONORABLE THE

COUNCIL,

AND THE HONORABLE THE

SENATE,

AND

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES,

OF THE

Commonwealth of Massachusetts,

MAY 26, 1784.

BEING THE DAY OF

GENERAL ELECTION.

By MOSES HEMMENWAY, A.M.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

In the House of Representatives,

May 26, 1784.

ORDERED,

THAT Mr. Smith, Mr. Bragdon, and Mr. Hill, be a Committee to wait on the Reverend Mr. Moses Hemmenway, and thank him, in Behalf of this House, for the Sermon delivered by him, this Day, before His Excellency, the Governor, the Council, and the two Branches of the General Court; and to request a Copy of the same for the Press.

SAMUEL A. OTIS, Speaker.

ELECTION SERMON.

Vth Chap. to the GALATIONS, 13 Ver.

“For brethren ye have been called unto liberty; only use not liberty for an occasion to the flesh, but by love serve one another.”

When Moses, being called by God from an obscure state of life, to stand before a court, and deliver the message of Heaven to them, would have excused himself, alleging that “He was not eloquent,” his false modesty was frowned upon; his pleas were all over-ruled; and he was animated to his great work, with a promise of special assistance from God: “I will be with thy mouth, and teach thee what thou shalt say.”

This instance may, I think, encourage us to hope for divine assistance, whenever we are by the providence of God called to undertake services for which we may seem too unequal. It is this hope emboldens me now to appear in this place: and it is also hoped that the present attempt, undertaken in obedience to authority, may be favorably accepted, or at least excused.

On this occasion, it will not, I presume, be expected, or desired, that I should attempt to go beyond my own line, or affect to discourse as a connoisseur in politics; but that I assist as a Christian Minister at the solemn acts of religious worship which are this day publicly offered by a Christian State to the supreme King of nations, whose ordinance civil government is; from whom all the authority of rulers and all the rights of subjects are originally derived; to whom the mutual duties of all orders of men are to be ultimately referred; and by whose blessing alone, communities, as well as individuals, can be happy.

The knowledge of ourselves is confessedly a capital and fundamental point of true wisdom. “The proper knowledge of mankind is man.” And of this there is no branch which more deserves the attention of everyone, than to understand our duty on the one hand, and our rights and privileges on the other. For want of clear and just apprehensions of these things, some have been ready to imagine that there is a kind of opposition between duty and right; or in other words, that the bonds of duty are a restraint and abridgment of liberty; and that liberty is a license to do whatever we please.—Hence different men have inclined to different extremes. Some by urging the obligations of duty in such a manner as tends to beget and cherish a spirit of bondage, and by lying heavy burdens on the consciences of men in things where God has left them free, have entrenched on the rights and liberties of mankind. Others, in their unguarded zeal for liberty, have relaxed the bonds of duty, and have given and taken too much encouragement to licentiousness, “using liberty for an occasion to the flesh.”

But our duties, and our rights or privileges, if rightly stated, are so far from interfering, or being inconsistent, that they mutually infer, establish, and support each other.

The apostle, in the words now read, appears to have had both the mentioned extremes distinctly in his view. As there were some who, by endeavouring to impose the observance of the abrogated ordinances of the Jewish law, encroached on the rights and liberty of Christians, St. Paul asserts these their rights, reminds his Christian brethren that Christ had made them free, and exhorts them to stand fast in their liberty to which they were called, and not be entangled with a yoke of bondage. At the same time he cautions them against the opposite extreme of abusing liberty for an occasion to the flesh; or of indulging themselves in a carnal licentious life; and then directs them “by love to serve one another,” and not think such mutual subjection to be any way unsuitable the honor they were called to, of being the Lord’s free men.

But whatever may be the special occasion of the words, and however we may expound them in reference to that occasion, we may, I think, be allowed to consider them as applicable to all those liberties which belong to us either as men, or as citizens, or as Christians. GOD has called us to liberty in all these different respects; and the gospel furnishes us with a good warrant to assert and claim these our rights. And though the main design of the sacred writers be to instruct us in the great concernments of our eternal salvation; yet they have also given us to understand, that liberty, in a more general sense, is our indefensible right. Christianity is indeed alike favorable to the liberty of subjects, and the rightful authority of rulers; and is the best security and support of both in their proper consistency with each other. And we are more beholden to the oracles of GOD than to the schools of philosophy, for just and generous notions of the rights of mankind.—A Christian, besides his peculiar spiritual privileges, holds his natural and civil liberty by a stronger handle than any other, and can maintain it to better advantage. He has by the gospel, a new covenant right to the common privileges of humanity, as well as to those special ones he is entitled to as a child and heir of GOD. That state of liberty to which he is called, and which he is authorized to claim and maintain, comprehends those natural and civil rights which belong to him as a man, or as a member of the commonwealth, as well as those special privileges which appertain to him as a subject of the kingdom of heaven. If I should therefore take occasion to offer some considerations on LIBERTY in this general view, the argument would, I conceive, be not foreign to my text, nor unsuitable to the present solemnity, nor unworthy of the attention of this grave and respectable audience.

Here are three points which require to be distinctly considered, as the time will allow: and I shall take them in the same order in which they lie before us in our text.

First. That GOD has called us to liberty?

Secondly. Liberty ought not to be used for an occasion to the flesh, or a pretence for carnal and licentious indulgencies.

Thirdly. It is our duty, and no infringement of our rights and privileges, to serve one another in love.

First. GOD hath called us to liberty.—

It is his declared will, that mankind should be free. The cause of liberty is the cause of GOD, which he approves, favors, and befriends. The law and light of nature make it evident that liberty is the right of all mankind. But the scriptures make it yet more evident that the people of GOD, the subjects of his heavenly kingdom, are entitled to, and invested with, this invaluable privilege, of which they have in the gospel an authentic charter, ratified, sealed, and sworn by GOD himself.

But it seems necessary that we here examine what we are to understand by that liberty which we claim as our right, by virtue of a Divine grant. For thou we are generally forward to profess ourselves to be its friends and advocates, and the love of it is said to be natural to us; yet there are many who do not well understand what they say, or whereof they affirm, in their flourishes on this subject. Indeed, if the matter be duly considered, we shall have reason to think that none but persons of real virtue are heartily friendly to true liberty, or desire the enjoyment of it either for themselves or others, whatever flattering encomiums they may bestow upon it.

When we speak of liberty as our right or privilege, we must be supposed to mean something valuable, dignifying, and desirable; something which our nature and state are capable of; something which is consistent with our moral agency, and our being under the obligations of law, and duty to our maker and our fellow-creatures.

Hence it follows clearly, that human liberty cannot consist in lawless licentiousness, or in being independent, and not subject to any authority; or in being allowed to invade the rights of others; to act unreasonably, and make ourselves and our fellow-creatures miserable. Far be it from any of us to imagine that the state of liberty, to which God has called us, dissolves the bonds of our duty, or confounds the essential differences of right and wrong: or to conceive that an exemption from the obligations of morality, and from subjection to rightful authority, would be any desirable privilege.—A lawless person is the basest, most odious and contemptible creature in the world.

Every man is necessarily subject to the authority of God. This is indeed an argument of our imperfection and dependent state. But we are so far from having any reason to be uneasy at it, that it is matter of joy and glorying to us that the Lord is our king. And his authority over us is so far from depriving us of any desirable liberty, that it is indeed the basis, guard and security of it. We therefore claim it as our right to be free from every yoke of bondage which can justly be accounted any grievance, because we are the servants of God, who allows none to tyrannize or usurp authority over any, and forbids our submitting to such unauthorized claims. And though we are required to be subject to our lawful superiors in families, in church and state, yet God requires us to yield this obedience not with a slavish, but a free and liberal spirit—we are to be subject to the higher powers in the Lord, and for the Lord’s sake, whose ordinance they are. And while we obey their lawful commands, it is our right and duty to disown them for our absolute masters. For we are not the servants of men, but of God alone.

If I should attempt a definition or description of liberty in general, considered as a right or privilege claimable by mankind, I would say that it consists in a person’s being allowed to hold, use and enjoy all his faculties, advantages, and rights, according to his own judgment and pleasure, in such ways as are consistent with the rights of others, and the duty we owe to our maker and our fellow creatures. Liberty must never be used but within the bounds of right and duty. God allows us not to hold, use, or enjoy anything to the injury of anyone. A licence to do wrong and encroach on the rights of others, is no part of that liberty which God has granted us; nor is it any restraint of our true freedom for us to be restrained by laws from wicked, unreasonable and injurious actions.

But that we may understand more distinctly the nature and extent of our liberty under the government of God, we may consider ourselves in three different states—1st. As individual persons in what is called the state of nature, that is previous to such confederation as forms a civil community.—2dly. As united and incorporated into a political society.—3dly. As members of the church of God.—Answerably to these several states or capacities, we may consider that liberty which we claim as our right as coming under a threefold distinction and denomination: supposing anyone to be in a state of nature, he has then a right to NATURAL LIBERTY: if we consider him as a member of a civil body, he has a right to CIVIL LIBERTY; and if a member of the Christian church, he is entitled to CHRISTIAN LIBERTY.

NATURAL LIBERTY does not consist in an exemption from the obligations of morality, and the duties of truth, righteousness and kindness to our fellow men; nor does it give anyone a right to seize by force or fraud whatever he may have a mind for, how much soever it may be to the damage of others; as some have most absurdly taught. The obligation of the law of God, which we are all under, and which requires us to love our neighbour, and do as we would be done unto, does not take its force from human compacts. Our natural rights are bounded and determined by the law of nature, which binds us to be subject to the will and authority of God, to love and worship him; to be just and benevolent to our fellow creatures, doing them all the good in our power, and offering no injury or abuse to anyone. It is therefore no violation of our natural liberty and rights for us not to be allowed to do wrong, and to be restrained by force and punishments, from invading the right and property of others.

But in a state of natural liberty, everyone has a right to be exempt from subjection to the authority of any man. There is also a right to think, speak, and act freely, without compulsion or restraint; and to use our faculties and property as we please, provided that none are thereby injured, nor the obligations of morality infringed. Liberty of conscience is also the natural and unalienable right of everyone: a right of which no man can be justly deprived; which can never be forfeited, never given up to anyone upon earth. Our Supreme Lord allows us not to subject our consciences to the authority of any but himself alone. If therefore anyone should consent to give up this previous branch of liberty, and acknowledge any man as the Lord of his conscience, such an unwarrantable act would be null and void.—In a state of natural liberty, men have also a right to form such associations with others, and enter into such confederations, and submit to such laws and constitutions, as shall be for the general good. In other words, they have a right to form into a civil society, and authorize fit persons to exercise the powers of government necessary to effectuate the good ends for which the social union is formed.

But it is to be carefully remembered, that no man has ever any rightful liberty to consent to any constitution or compact inconsistent with his own safety and welfare, and that of his fellow men: for instance, to authorize any to govern unrighteously and oppressively.—The establishing a pernicious tyranny is a great injury to mankind, and so is beyond the limits of our natural rights. No human laws or covenants can give any authority or validity to an act which God disallows: and if any people have been so imprudent and blameable as to consent to, and put themselves under a tyrannical government, they are so far from being bound in honor or conscience to support it, that it is their duty to overthrow and abolish it as soon as they can—As individual persons in a state of natural liberty have no right or leave from God to make themselves miserable, or to injure and oppress others; so they have no right or leave to join and concur with others in any measures inconsistent with the interest of mankind.—And as no society has a right to oppress any of its members, it cannot convey to anyone a rightful authority to oppress. All tyrannical government is therefore an unauthorized invasion of the rights of mankind, and no obedience is due to it.

A just apprehension of our natural rights is very useful and necessary in order to our conceiving aright the nature and extent of CIVIL LIBERTY, which is next to come under our consideration. And we are now to view mankind as united together in political societies or states, that so the united wisdom and strength of a community may be employed to advantage for the good of the whole, and of the several individual members, in a consistency with the public interest.

That the human species were formed and designed for civil union, appears from the rational faculties, and social affections which God has given them. It appears also from their moral character, and state, and the need they stand in of mutual assistance, in order that their rights and properties may be better secured, and enjoyed to greater advantage. The state of nature, tho’ attended with some peculiar privileges, is yet very unsafe, and subject to great and manifold difficulties and disadvantages. Civil polity is evidently for the interest of mankind: and in a well constituted and regulated state, subjection to civil government is no way prejudicial to true liberty. For though some of our natural rights and property are, as it were, put into a common stock, under the management of the community; yet this is supposed to be done by our own free consent, and in the prudent exercise of our natural liberty. And as each one continually receives his share of the vast profits thence accruing to the community, and has his most important rights so secured and improved as to be much more valuable; he is, upon the whole, a great gainer by all the expense he is at for the public service, and enjoys more liberty for the restraints he submits to.

Nay, further: since civil polity is evidently for the good of mankind, and since no individual ought to hold his natural right of independence, if it stands in opposition to the general interest—it would seem that men’s entering into civil society was a matter of duty as well as right; and that they may be justly compelled to it, when the general interest so requires.—

Now, in every civil body there must be a governing authority and power, to be exercised on the behalf of the community, over the several members—ordering matters of common concernment for the good of the whole: and the rightful authority of those who are entrusted with the powers of government, is the ordinance of God. They are not only the trustees of the state, but the ministers of GOD, who ratifies their commission, requiring every soul to be subject to them, and not resist them on their peril, in the due exercise of their authority.

From the brief account here given of a state of civil polity, it is plain that civil liberty divides into two branches, which will require some distinct notice. It includes the freedom of the state considered as a system or collective body. It includes also the freedom of the several parts or members of which the community is composed.

The FORMER BRANCH of civil liberty is possessed by a people, when they hold and are allowed freely to exercise the rights, powers, and prerogatives of FREE AND INDEPENDENT STATES. These are much the same with those of an individual in the state of natural liberty and independence; of which we have given some account: and are alike limited by the law of nature and of GOD, who is the sovereign of nations as well as of particular persons. But it is to be observed, that free states have also right to rule their own members: whereas individuals have no natural right which properly answers to this.

Notwithstanding what has been so boldly pretended by some, of the transcendent authority, and omnipotency of the supreme civil power, and of those who are entrusted with the administration of government, it is plain that the whole authority of a state over its members is limited. The liberty and authority of a free commonwealth to enact and execute laws and ordinances for the public good, must be always understood with this limitation, viz.—that the sacred rules of righteousness are not to be violated at any rate. The liberty and sovereignty of a state implies no right or authority to serve its own interest by unjust or immoral measures; even though such measures should be thought for the public advantage. It has no rightful liberty, under any such pretence, to violate the laws of GOD, or the rights of any of its members, to oppress or injure any of its neighbours, or falsify the public faith. That common maxim, “that the safety and welfare of the people is the supreme law,” how much soever it has been applauded, is, therefore, unfound morality, unless it be understood and applied in an invariable agreement with that divine rule, “that evil is not to be done that good may come.” Every man has his private, unalienable rights, particularly the right of conscience, which he ought to hold and use without restraint or disturbance from any human authority. There can scarce be a worse mistake than to think that the laws of morality must give way to serve any interest, whether public or private; or that all personal rights in the subjects are absolutely at the disposal of the supreme civil power.

The liberty of a state may be violated and abridged several ways. It is so when a foreign authority, to whom the state owes not subjection, claims and exercises a governing and controuling power over it. This is also the case when a part of the state, without right, seizes on the powers of government, or hinders the free exercise of them: or, when those who are entrusted with authority, stretch their prerogatives beyond due bounds, to the enslaving of the people. If the whole authority of a state over its members be limited, as has been shewn, much more is the authority of rulers so, who have not the whole authority of the state put into their hands to be used by them as they please, but only so much of it as is judged to be needful to fit them to answer the end of their appointment. The supreme civil authority remains always in the community at large, whose will and order is the supreme law of the state. And they have always a right, when their rulers are evidently unfaithful and unworthy of their trust, to restrain them and revoke their powers.—They have a right to alter and reform their laws when they are found to be pernicious; any law or compact to the contrary notwithstanding. Civil rulers are indeed to be considered as the ordinary representatives of the state, and the laws enacted by them as the will and law of the state, when the contrary does not appear: but surely such laws ought not to stand in force against the manifest will and interest of the community.—For a people to be so enslaved, either to their rulers, or even their own laws, as not to be able to exercise their essential right of sovereignty for their own safety and welfare, is as inconsistent with civil liberty, as if they were enslaved to an army, or to any foreign power. Whatever form of government a people may choose to be under, the supreme civil authority remains always attached to, and diffused through the whole body: nor can they give it up without injuring and enslaving themselves, their fellow-citizens and their posterity, which they have no natural right to do.

It is therefore a wise provision in our frame of government, that an orderly way is left open, and pointed out, for the state to revise its civil constitution, and make such amendments as may be found necessary. Alterations of this nature, are not, indeed, to be attempted for light reasons, since they are always attended with inconvenience and danger. But when the safety and interest of a people requires that such alterations be made, they have an indefeasible right to make them.

Having thus far considered the first great branch of civil liberty, and then touched a little on the rights of a free state, I will now attend to the other branch, which includes the rights and privileges of the several members of a political body IN THEIR INDIVIDUAL AND PERSONAL CAPACITY.—Liberty is the right of every member, as well as of the whole body, or system. And a person may justly be accounted a free citizen, when he is allowed to hold and use his natural rights and faculties, together with the civil privileges proper to his rank in the commonwealth, according to his own judgment and pleasure, in such ways as are consistent with his obligations to the community, and his fellow citizens, and with the just and reasonable laws of the state.

The order and interest of a civil society require that there should be different ranks of men, with different civil rights and privileges annexed to them; and subject to different restrictions. Nor is the true liberty of any rank infringed by this subordination, but rather secured, improved and enjoyed by all to better advantage. But through the several ranks in a political system may rise one above another in a long scale of subordination, yet we may conveniently distribute them all into two general classes, viz. Rulers and Subjects. Indeed in a free state the right of authority and the duty of subjection are interwoven, and, as it were, incorporated together through the whole system, so that they are mutually tempered by each other. They who are vested with most authority are yet fellow-subjects with their inferiors, who are governed by them. They are not only alike subject to the law of GOD, but also to the law and authority of the state, whose ministers they are. And the lowest orders of men have a rightful share in that sovereignty or supreme civil power which is lodged in and diffused through the whole community.

As the bounds of civil liberty are determined by just and reasonable civil laws, it is plain that when RULERS are allowed freely to use the powers committed to them for the public good, and enjoy the privileges annexed to their rank, they then enjoy that civil liberty which is their right. But when they are overawed and controlled in the exercise of their rightful authority, or are not allowed the privileges they have a right to, their civil liberty is then infringed. But as rulers have no rightful liberty to claim and exercise powers to which they are not entitled by law, or to violate the rules of righteousness, or to oppress the community, or any of its members, by hindering them from holding and using their just rights, their liberty is not infringed in the least, if the state interposes its sovereign authority, when it is necessary to restrain them from effecting unrighteous and pernicious designs; which, whenever they attempt, they act without authority. GOD never gave them authority for any such purpose: the people never meant to do it: they could not do it if they would: they had no such authority to give.

And though subjects, as such, have no rightful claim to the peculiar civil privileges of rulers, they have yet a right to civil liberty, and to all the privileges of citizens of their rank, unless they have forfeited them by some high misdemeanor. And they may justly be said to enjoy this their right, when they are allowed the free use of their natural unalienable rights, the most important of which are, the rights of conscience; and also to speak and act, to use and dispose of their property, to hold and enjoy every rightful privilege, without disturbance or control, in such ways as are not injurious to any, or contrary to the reasonable laws of that civil body of which they are members. And though such laws as lay the subject under needless and burdensome restraints may justly be accounted an abridgment of liberty, yet no one has any reason to complain that he is denied the liberty of a free citizen, when he is restrained by human laws and penalties, from vice and immorality, and obliged to yield due obedience to civil authority, and observe such ordinances, and pay such taxes, as are necessary for the support of government, and to maintain the order, peace and welfare of the commonwealth.

Natural and civil liberty is the right of every man and member of a civil community. But there is yet another branch which belongs peculiarly to Christians, and which we may therefore fitly term, CHRISTIAN LIBERTY.

The gospel does not curtail any of our natural rights, or civil privileges, but allows and acknowledges them, and ratifies the right which Christians in common with other s have to the enjoyment of them. But the new covenant contains a grant of special privileges, and those of the highest importance. It calls us to, and invests us with the “glorious liberty of the children of God.” The apostle seems to have had the peculiar privileges of Christians most directly in his view, when he said in our text, “Brethren ye have been called to liberty.” It seems therefore but fit that some distinct notice should be taken of these, though the time and present occasion will not allow of enlargement.

The liberty we are called to as Christians, does not in any measure relax the obligation we are under to be subject to the authority and laws of GOD, and also to submit ourselves to those who, under him, have rightful authority, whether economical, political, or ecclesiastical. But the gospel calls us to liberty from the bonds of guilt, the condemning power and curse of the divine law, and from the obligations to punishment which sin had laid us under, which is a most miserable bondage. We are also called to liberty from a slavish subjection to the power of sin, and of Satan the God of this world, who rules in the children of disobedience, and leads them captive at his will; than which what slavery can be more wretched, abject and ignominious? We are called also to liberty from a slavish spirit in the service of GOD, and of one another; so that a Christian is not driven on in the way of his duty against his inclination, but acts with a cheerful, free, and ingenuous spirit. “Where the spirit of the Lord is there is liberty.” We are also discharged from subjection to any master or dictator on earth, in matters of faith and worship; and are to acknowledge no lawgiver to the church but Christ alone. We have liberty to use the ordinances instituted by Christ for the edification of his church, and to have communion with him, and his saints in them, and that without any human inventions, or unscriptural terms of communion imposed on us. Finally, we may think, and speak, and act, and use our spiritual privileges with all freedom, according to the measures of wisdom and grace given to us; nor may any human authority forbid or restrain us from it.

I have taken the freedom to enlarge a little in opening the nature and stating the extent and proper bounds of NATURAL, CIVIL and CHRISTIAN LIBERTY; because the right understanding hereof might, I conceive, be of great use to us: and at this day in particular, it may seem to be a matter which needs to be considered with some special attention. In the next place, I am to shew “that we have been called to liberty.” It belongs to us by virtue of a divine grant—we claim it as our RIGHT; and blessed be GOD, we hold and enjoy it as our INHERITANCE. The expression “ye have been called to liberty,” may be taken both ways, and may signify either that GOD has given us a right to liberty, or that he has given the possession and use of this right. In the former sense, he calls us to liberty, by declaring to us that it is his will that we be free, and requiring us to assert and maintain our right. In the latter sense, he calls us to liberty, when he gives us the possession of it, and breaks those yokes of bondage which had been imposed upon us.

That God has called to the RIGHT of liberty; that he allows us to claim and maintain it, against all who would bring us into bondage; that he favors the glorious cause, and would have us stand up for it, is evident from the light of nature, and from the oracles of divine revelation.

The light of our own REASON and CONSCIENCE, that “candle of the Lord” which he hath put within us, makes it plain that we have a right to be free. There is no need of long and subtle trains of reasoning in the case. We appeal to the moral sense, the inward feelings and resentments of every honest heart. Can it be right that men, made in the image of God should be slaves? That fellow servants of the same Lord should usurp and tyrannize over one another? Are not the pretences urged to justify such usurpation so weak, so pitiful, so unfair, that it is a painful exercise of patience to a man of reason and virtue, and generous feelings, to have his understanding and heart affronted, and harrowed with them? It is true, the interests of society require subordination: but this deprives none of liberty, but helps all to enjoy it better. In short, if equity, requires us to do to others as we would that they should do to us; if the plainest and surest dictates of our reason are to be believed; if the law of nature be of force, then liberty is our right; and consequently it is the will of God that we be free. Nor is it easy to determine, whether the injustice of those who would put a yoke of bondage on their brethren, or the meanness of those who would tamely stoop to take it on, be the greater reproach to human nature.

If we now turn our eye to the oracles of DIVINE REVELATION, we shall find clear and manifold evidence that God approves and favors the cause of liberty, and that tyranny is most offensive to him—This appears in his delivering the Israelites from a state of miserable bondage, and punishing their oppressors with a mighty hand, and stretched-out arm. It appears in the laws and form of government he gave them; whereby liberty and property were secured to everyone. It appears in the awful threatnings denounced by the prophets against the enslavers and oppressors of mankind; and which have been terribly executed. It appears in the whole strain, spirit, and tendency of the doctrine and religion taught and inculcated throughout the scriptures; which is to promote the practice of goodness, righteousness and truth, with all other divine and social virtues; and to dissuade men from all acts of injustice or unkindness, whereby the rights or liberties of any might be violated. It appears further, from express directions and exhortations to Christians, that they stand fast in their liberty, and be not entangled with a yoke of bondage; nor be the servants of men; nor call any man master upon earth; nor exercise lordly dominion over one another. Finally, it appears from the example of Christ, and the apostles, prophets, and holy men, whose characters and conduct are recorded for our imitation; who spoke and acted with the most ingenuous freedom, and most reverse to a base servile spirit. These hints might be copiously illustrated from the scriptures, 1 which might be both instructive and entertaining. But I must wave it.—

But this call to liberty, which we are now considering, may be understood to import God’s giving us the ACTUAL POSSESSION of, as well as a right to this invaluable privilege. And here this divine goodness deserves our grateful notice, that, through the kind and wonderful disposals of providence, mankind enjoy so much liberty. For though it is a melancholy truth that there is much tyranny and oppression in the world, and all are more or less entangled with yokes of bondage in some kind, and are not so free as they ought to be; yet it must also be acknowledged, that as every degree of liberty which men enjoy, is the gift of God, so there are none but have a share of this sweet blessing: and indeed the greater part enjoy considerable degrees of it.—Notwithstanding the despotic claims of tyrants, we see that their pernicious and oppressive power is restrained by God in ways innumerable. These fierce beasts are chained, their horns are shortened, their mouths muzzled, and they are diverted from their purposes. By this means men often enjoy no small share of liberty, even under those forms of government which are most unfriendly to it.

It is, however, to be observed, that as God has a sovereign right to deal out his own gifts in what measure and proportion he pleases, so he calls different men to different kinds and degrees of liberty. Though the natural rights of men may, in general, seem much alike, they being, in this respect, “all FREE and EQUAL;” yet it is in different degrees that they are permitted to use them. According to the different civil constitutions which men are under, their civil liberty is larger, or more restricted.—And, indeed, under every form of government it is necessary that some ranks and denominations of men should be allowed more ample civil privileges than others. And as to Christian liberty, this is the peculiar right and privilege of the disciples of Christ: no others have any lot or portion in this matter. And though all Christians are free indeed, and are by the special grace of GOD, entitled and admitted to the liberties and privileges of his heavenly kingdom; yet all do not enjoy them in like measure: nor is the liberty of any perfect in this world; but is more or less entangled and restrained by the power of sin and Satan, and the men and things of the world. It will, however, gradually work itself clear of all these clogs; and our call to the glorious liberty of the children of GOD, will, in the heavenly state, have its full effect.

As it is a great happiness to a people when their civil constitution and laws are favorable to civil and religious liberty; so there is perhaps no part of the world more happy, in this respect, than these United State, or that have been called by Divine Providence to the possession and enjoyment of such a degree of liberty as we have been.

If what has been offered under this first head should seem too long, abstruse, and speculative, I will endeavour to make some atonement by being shorter, plainer, and more practical in what remains.

OUR SECOND GENERAL POINT is, “That they who are called to liberty should be careful not to abuse it for an occasion to the flesh.” They should not run wild because they are free; or take encouragement to indulge themselves in a lawless and licentious temper and practice.

It is a great evidence of the weakness and folly of men that they, in general, can no better bear that state of freedom to which they are called; and when they have such a price in their hands, they so seldom use it wisely and soberly, and to advantage. Their lusts and passions are ready to break out into wild excesses when they find themselves free from outward restraints. The apostle, well aware of this danger, has left this caution in the text, “use not liberty for an occasion to the flesh.” And St. Peter also speaks to the same effect; “As free, but not using your liberty for a cloak of maliciousness.” We are pleased with the thought of being free; but how often do we shew that we have not a heart rightly to improve our privileges? When we get the helm into our own hands, what wild courses do we often steer! When we find ourselves at liberty to direct our steps, how prone are we to turn aside into crooked paths!

We cannot therefore be too much on our guard against these licentious abuses: for, besides our liableness thereto, it should be considered that they are highly criminal. When we make an ill use of liberty, we shew ourselves most unworthy to have it, and deserve to have our talent taken from us. It is ungrateful to GOD, and injurious and uncharitable to men. It turns our glory into shame, and exposes to reproach that perfect law of liberty by which we profess to be governed.

The public abuse of liberty draws after it also a train of the worst consequences. It is, we may say, “the root of all evil.” It makes our privileges become our grievances, and turns our blessings into curses: yea, it destroys liberty itself, and is an inlet to tyranny and slavery. True liberty is a tender thing: it languishes and dies under licentious abuses. Rulers, by abusing their liberty, betray their trust; and their authority degenerates into tyranny. And when subjects abuse their privileges, and become disorderly, ungovernable, undutiful, factious, and irreligious, their social union is greatly weakened, and they suffer the worst effects of slavery, while they have only an empty shadow of freedom. It is true virtue, and religion, and subjection to the laws and ordinances of GOD, that can only preserve the liberty of any people. Without this, declarations of rights and forms of government are vain: And I know not whether it be not better for a licentious people to be under a despotic government than any other. Such a people may well expect to come under such a government, as the natural and penal effect of their vices—Thus it befell the Israelites as they had been forewarned: “That if they would not serve the Lord they should serve their enemies, who would put a yoke of iron on their necks.”

No less prejudicial is the abuse of religious liberty to the spiritual interests of the Christian church. From this source an inundation of infidelity, and manifold corruption in doctrine, discipline, worship, and practice, with most uncharitable contentions, and schisms, have issued, which have made terrible havoc in God’s heritage. Hence—But I must leave it to my hearers to pursue these reflections. The evils flowing from this source are so many, that it is impossible to give a detail of them.

For the like reason I can only suggest a few short and general hints, respecting the several ways in which we might be in danger of abusing our liberty; a point highly worthy of special attention, and which I had thought to have considered more particularly: But on such a subject one would hardly know where to stop. I shall therefore only say, we should take heed that Liberty of thinking for ourselves, or the right of private judgment become not an occasion of infidelity, or skepticism, or of our being carried away with unsound doctrines, and our minds corrupted from the simplicity that is in Christ. Liberty of speaking our thoughts must not be abused to the dishonor of God, and religion and virtue; to the encouragement of vice, or hurtful errors; to the detriment of the commonwealth; or to the injury, grievance, or scandal of anyone. Liberty of conscience must not be abused into a pretence for neglecting religious worship, prophaning God’s Sabbaths and ordinances, or refusing to do our part for the support of government and the means of religious instruction. In a word,–as we would avoid the abuse of liberty, let us all take heed that we use it not irreligiously, by transgressing God’s commands, or by neglecting or prophaning his worship and ordinances: nor undutifully, by refusing due honor and subjection to rightful authority, in families, churches or commonwealth: nor injuriously, unkindly, and uncharitably, to the wrong, the damage, the grief and offence of our brethren: nor inordinately, exceeding the bounds of moderation, sobriety and expediency, even in things that are in themselves lawful.

As a preservative from these, and all other abuses, let it be our care thoroughly to imbibe the spirit of the gospel, “that perfect law of liberty,” and have our sentiments, our temper, and manners, formed by its divine doctrines and rules. Let us cherish in our hearts the fear and love of God, with that benevolence and charity which is the fulfilling of the law, and which only can effectually correct the inordinacy of those selfish affections which are the malignant root of these abuses. And, to add no more, let it be our care to understand, distinctly, the nature and extent of our liberty, and of our duty, in their connection and consistency with each other; and that our freedom can no otherwise be maintained and exercised, so as to be any real privilege, than by our being the servants of God, and “by love serving one another.”

This was the THIRD POINT contained in our text, viz.—That it is our duty, and no infringement of our liberty, to serve one another in love. Though God has made us free, yet it is no disparagement to be, in a liberal sense, servants to each other: nay, it is our honor to be so-this gives true dignity to men of the highest rank. It is a very honorable character given to David, a great and excellent King, that he SERVED his generation by the will of GOD—And a far greater King, even David’s Lord, and the heir of all things, when he assumed our flesh, and dwelt among us, “came to minister,” and “was with us as one that serveth.” We ought, as the apostle directs to “be all of us subject one to another.” Rulers, as has been observed, are all of them FELLOW SUBJECTS with other members of the civil body, and hold their authority under the state. They who exercise the highest ordinary powers of government do it as the trustees and servants of the people; and it is their duty to serve the Commonwealth faithfully, and not tyrannize over any. And it is no less the duty of everyone, whatever his rank may be, to perform the services properly incumbent on him, with like fidelity. But as the duty of mutual subjection was considered at large upon the last anniversary of this kind, I shall insist no further upon it.

There is one thing, however, our text suggests, relative to the mutual service required of us, which should not be passed over unnoticed: and that is the principle by which we are therein to be moved and actuated. “By love serve one another.” Love must be the vital spring to put every member of the body in motion, and set the whole system at work in a circulation of services, and then they will be all free. We act most freely when we are prompted by love. If we have a sincere and warm affection one to another, our services will not be performed with slavish reluctance, but in the full enjoyment of liberty. A ruler, or a subject, who is of a truly public spirit, who tenders the interest of his fellow-citizens, and sympathizes with them in their joys and sorrows, will rejoice in an opportunity of serving them; nor will he grudge the pains it costs him. Love makes his services easy, pleasant and free: and he never enjoys his liberty more to his own satisfaction, than when he is most engaged in the service of his generation.

The REFLECTIONS with which it is time to close this discourse must be confined to the present occasion.

We in this land have great reason to bow our knee before God in humble thankfulness that he has called us to liberty. He has not only given us a right to natural and civil liberty in common with others of our fellow men, but has also given us the possession of this invaluable blessing, and that in such a degree as few in the world are favored with.—It is an happiness almost peculiar to these United States, for an enlightened people to have the opportunity of deliberately forming and freely choosing the plan of government under which they are to live. And though we do not presume to say that there is nothing amiss or defective in our civil constitution; (it is the prerogative of God alone to have his work all perfect) yet the form of our government, and spirit of our laws are, to speak modestly, favorable to the free enjoyment of our natural rights, so far as can consist with our political union, and the interest of the commonwealth. And we should be unthankful to GOD and man, not to be sensible of, and own the wisdom and fidelity of those who had the chief hand in this important and arduous work. Besides the ample civil privileges which are secured to all orders of citizens, we rejoice to find that the right of enslaving our fellow men is absolutely disclaimed. That inhuman monster SLAVERY, which has too long been tolerated, is at length proscribed, and is no longer suffered to lie with us. And it is devoutly wished, that the turf may lie firm upon its grave. The rights of conscience also, in matters of religion, are strongly guarded, and the door is happily shut and fast barred against ecclesiastical establishments by human laws, which have done so much hurt in the world. Everyone is now fully at liberty to worship GOD in the way which he judges to be most acceptable to him, while he demeans himself as a good citizen. Nor should we forget our Christian privileges in having the ordinances of the gospel administered among us, which we may with all freedom attend upon for our spiritual edification, if it be not our own fault. Add to this the sovereignty and prerogatives of FREE AND INDEPENDENT STATES, which at length are acknowledged and solemnly recognized as belonging to us. How much reason have we to account ourselves happy that our lot has fallen to us in pleasant places, and we have so goodly an heritage. Blessed are our eyes which see the things we see, and our ears which hear the things we hear. And blessed be the Lord who hath visited and redeemed his people; who hath called them to liberty, and grante4d them the blessings of peace, that we, being delivered out of the hand of our enemies, might serve him without fear, in holiness and righteousness before him, all the days of our life.

And is it not then our duty to stand fast in this liberty to which GOD hath called us? We should shew ourselves most unworthy of our birthright, if, like Esau, we should sell it for a contemptible price; nay, if we should sell it at any rate. Liberty is a pearl of too great price to be bartered. We may fitly accommodate the words of Solomon; “She is more precious than the rubies; and all the things thou canst desire are not to be compared to her. Length of days are in her right hand, and in her left are riches and honor. Her ways are ways of pleasantness, and all her paths are peace. She is a tree of life to them that lay hold upon her; and happy is everyone that retaineth her.” We have done ourselves great and lasting honor by our brave, vigorous, and, by the blessing of GOD, successful and effectual defense of our civil liberty. Though in respect of right, we were free born, as every man is; yet it is with a great sum that we have obtained the possession of this our inheritance, clear of the encumbrance of being dependent on, and subject to the control of foreign power. To secure the continued enjoyment of the prize which has been won with so much expense of blood and treasure, is surely an object worthy of the attention of everyone. And we can do nothing better for this purpose than to make it our most serious care to use our liberty aright, that is, piously, equitably, charitably, and soberly; and that we abuse it not for an occasion to the flesh.

This caution against the abuse of liberty ought to sink deep into our hearts; for here seems to be our greatest danger. Our conduct, at the time when attempts were made to wrest our privileges from us, is a witness for us, that we were not insensible of the value and importance of them. By the blessing of Almighty GOD our struggle is now happily terminated, and we are now unbuckling the harness, having accomplished our warfare with desired success. WE ARE A FREE PEOPLE. We have maintained our claim to liberty effectually against those who disputed it; and have indeed more liberty than we at first thought of claiming. And if we are so wise and sober as not to abuse it, we trust in God that we shall be happy ourselves, and leave this fair inheritance to succeeding generations. But we flatter ourselves, if we think that our having legal securities of civil and religious liberty will ensure our prosperity. Nay, if our privileges are licentiously abused, we shall have no solid advantages of them, but they will rather prove, as was said, intolerable grievances. The name itself of liberty has been reproached, I had almost said blasphemed, on account of these abuses, which have given occasion to some to call it a popular idol. And we shall make an idol of it indeed, if it draws away our hearts from the service of God, and emboldens us to strengthen ourselves in wickedness, and bless ourselves in our own hearts, saying, we shall have peace though we walk in the imagination of our hearts.” That people only can be truly free and happy who have the Lord for their God, their law-giver, and king; and who demean themselves as his obedient servants. O that there were such an heart in us, that we might fear the Lord, and keep all his commandments always, that it might be well with us, and with our children forever.”

Our honored RULERS will consider themselves, as, under God, the guardians of this PRECIOUS DEPOSITUM, which divine providence has put into our hands. In this light we view them, and not with an evil eye of malignant jealousy, as those who would willingly rob the commonwealth of its crown, or steal the jewels out of it; that is, abridge our privileges, to extend their own prerogatives. As the places of highest authority are disposed of by the free suffrage of the people, they are to be considered as marks of great confidence in the wisdom and fidelity of those whom they call to fill them; and as public testimonies to their merit. Nor will they take it amiss to be stiled the servants of the people; but will accept the title as it is meant, for a title of distinguished honor. For it holds equally true in a free commonwealth as in the church, that “He who is greatest, is most eminently servant of all.”

We have confidence in our civil fathers, that their upright and faithful endeavours will not be wanting to secure and perpetuate the blessings of peace and liberty, which God hath given us, and to promote the true interest of this people; and that their integrity will preserve them and us. While the measures of righteousness are faithfully observed in their administrations, we doubt not but that they will, by the blessing of God, be crowned with good success. “Unto the upright ariseth light in the darkness,” to direct, cheer, and comfort them, in their greatest difficulties and straits. It is “by righteousness that the throne of government is established, and the nation is exalted.” And indeed the grand secret of political wisdom is to maintain a steady, thorough and untainted integrity: a secret hidden from those serpentine politicians, who think it necessary to turn aside into crooked paths to compass their designs. Unfair artifices and intrigues may sometimes answer a present turn; but they do more hurt than good: they breed worse distempers than they remedy or prevent. Whatever designs cannot be carried by fair measures, had better not be carried by fair measures, had better not be carried at all. God will curse that policy which sets the rules of righteousness at defiance. If this sentiment should be ascribed to the simplicity of one who is unexperienced in the affairs of the world, it may be confirmed by the attestation of the great HARRINGTON, who says, “That the pretended depth and difficulty in matters of state is a mere cheat. From the beginning of the world to this day you never found a commonwealth where the leaders having honestly enough wanted skill enough to lead her to her true interest, at home and abroad.” And, that I may not seem to have gone beyond my own line, a yet greater authority may be adduced; even that of the wise and inspired king Solomon, who says, “He that walketh uprightly walketh surely; and the integrity of the upright shall guide him.”

Alas! for that people whose rulers think it can be good policy to break over the sacred rules of justice. We hope in God that the conduct of our public affairs will never fall into the hands of those who are given up to such an awful infatuation. If indeed we could persuade ourselves that the world was governed by chance, such a strict adherence to these rules might not seem needful, or fit to be insisted on. But under the government of a righteous GOD, we may be sure that unrighteous measures can never be for the true interest of a people. It is the blessing of GOD that must render the means successful we make use of to answer our ends. What madness then must be in their hearts who imagine that GOD will annex a blessing to the presumptuous transgression of his own laws!—It is ordered indeed for the trial and discipline or virtue, that it should sometimes have to struggle with great difficulties and opposition, which might be avoided if we would let go our integrity: but the avoiding these difficulties in this way, will, without fail, run us into much worse ones. The advantages of unrighteousness are dearly bought. If our country, nay, if the world can no otherwise be preserved than by violating the rules of truth and righteousness, IN THE NAME OF ALL THAT IS SACRED LET IT SINK. But while the throne of GOD stands unshaken, we may trust in him, and not fear that we shall ever be losers by our fidelity and obedience to his laws.

That corrupt craft, and those cunning contrivances, which politicians have often had recourse to in state affairs, when they were resolved to carry a favorite point at any rate, have been the disgrace of policy, and the pest of states. They who turn aside into these crooked ways, will soon find themselves in a perfect labyrinth. Tricking will soon sink a man’s credit and reputation, and lose him the confidence of mankind, which is of the utmost importance in order to a successful prosecution of designs of public concernment. Unfair artifices are an insult upon the moral government of GOD, who knows how to take the wise in their own craftiness and turn to foolishness the counsels of the Ahitophels, who applaud themselves most in their skill and address.

It may well discourage wise observers from attempting to promote the public interest by iniquity, that such attempts are constantly found to be of unhappy and pernicious consequence. The laws by which GOD governs the world must be quite altered, the course of nature must be reversed, before it can reasonably be hoped that unrighteous schemes will operate for the real advantage of a people. And it is the fervent wish of those who have the true interest of their country most at heart, that there may be a full and fair experiment made what effect a strictly righteous and equitable administration of government will have upon the national interest. And they have raised expectations, that in that case we should soon see our public affairs in a situation much to our satisfaction and honor, and the honor of virtuous policy, which would appear in its proper dignity after such a triumph over its intriguing rival. The eyes of the world are turned to observe our conduct at this important period, which will be likely to fix the stamp of honor, or the brand of infamy, on our national character. We hope our rulers will not be less tender of the honor of the commonwealth than of their own, or that of their families: and that they will not give occasion to any to apply to them what has been observed by some, “That such deeds have been often done by bodies or communities of men, as most of the individuals of which such communities consisted, acting separately, would have been ashamed of.” And it is also to be remembered (which ought much more to move us) that the eye of the great KING OF NATIONS is upon us to observe whether we will be obedient to his laws: and he is, as it were, saying to us in the words of the prophet, “Prove me now herewith, whether I will not open you the windows of heaven, and pour you out a blessing.”

As for those who sneer at righteous policy, integrity and public spiritedness, and who represent all men as being alike perfectly selfish, I shall only say, that if the picture of mankind which they give us was taken from their own hearts, we will not dispute their skill in drawing, but will own it may be a striking, yea, a shocking likeness of the persons who sat for it. But let them go—My honorable hearers know, as every honest man does, that there is such a thing in the world as integrity, and virtue, and public spirit, and that it is no hypocritical pretence.

As righteousness is the root and bias of liberty, I have not, I hope, wandered from my subject in inculcating a due regard thereto in the administration of government. And it is also hoped that the freedom of speech which has been used on this occasion, (a freedom which the presence of those before whom it has been taken, has no tendency to check, but rather to inspire and animate,) will not be deemed an abuse of liberty. But if more has been said than may be thought needful, or if any expressions should seem to warm or bold, they will I hope, be candidly imputed to an honest zeal for public virtue, and for the liberty, the interest, and the honor of my dear country; and to an earnest and inexpressible desire that this vast political structure, which to the wonder of the world has rose so suddenly as a temple of liberty6 in North-America, the building of which has been carried on so far with such happy success, may receive the finishing touch to the utmost advantage, and may stand as a glorious and lasting monument far more grand and magnificent than MAUSOLEUMS, PYRAMIDS, OR TRIUMPHAL ARCHES.

The present state of our affairs is such as calls for the utmost attention of our civil rulers, and affords them uncommon opportunities for services of the most important kind. It is, I think, needless, and might seem presumptuous, for me to go into a detail of those objects which claim their special attention: their own more just, penetrating, and comprehensive views, will readily suggest the vastness of their trust, in having the care of the liberties and properties, the religion and morals, the means of education and literary improvement, of this people; besides such regulations as are necessary to maintain and strengthen that connection between the several parts of this united system of states, which is of so much importance to the welfare of the whole. We are not insensible of the difficulties they have to struggle with,–and sympathize with them on that account. But these should rather animate than discourage them. THESE ARE THE TRIALS AND PROOFS OF VIRTUE, whereby it is distinguished from counterfeit pretences, and is found unto praise, and honor, and glory. If they are faithful they may expect to displease some: but they will have the applause of their own consciences, and of the best friends of their country: their children will rise up and call them blessed, and GOD himself will think on them for good. “The armour of light” will repel the darts of calumny which may be thrown at them. They will only need to stand forth in open day. The light will render them invulnerable; and their being known will be their security.—And GOD forbid that any of us should be backward to support them in their faithful endeavours, or that we should cease to pray for them, that GOD would be with them: that their hearts may be encouraged, and their hands strengthened with a double portion of his spirit: that they may be inspired with the wisdom, integrity, fortitude, and unfainting resolution necessary to prosecute and accomplish their designs for the public good. “We wish them a blessing from the house of the Lord; yea, we bless them in the name of the Lord.”

This day may well be accounted the day of the gladness of our hearts. We enjoy, at length, the blessings of peace and liberty:–Blessings,–for which, saints, now with God, have earnestly prayed—heroes, of glorious memory, have fought and bled—and patriots have worn out themselves with care, travail and exertion. The joy of reaping the harvest which has been sown and watered with so much tears and blood, is reserved for us. This day, UNITED AMERICA sees the issue and fruit of her travailing throes, and is satisfied. The fight of so sweet and lovely a birth, comforts and rejoices her, after her agonizing labor.

This day, we have the happiness to see our CONGREGATION, even the legislative assembly of the commonwealth, established before the Lord—our NOBLES from among ourselves—and our GOVERNORS proceeding from the midst of us. We view this august body as representing the whole republic, vested with its majesty and authority; the distinct branches of which unite and concentrate in the Governor, the common representative of the whole state. As his EXCELLENCY and his HONOR are here present, it would seem scarce decent for us to give them their due encomium, or to express freely how worthy we esteem them of the pre-eminence to which they are advanced; but their continued and often repeated election to the highest seats in the Commonwealth, speaks louder and more significantly than words can, the peculiar esteem and confidence of the people, and in such a way as leaves no suspicion of flattery.

We regard his EXCELLENCY in particular, as most eminently authorized to act as the guardian of our rights, and take care that the Republic receive no detriment. His prerogatives and powers we consider as a wise provision for our security against the pernicious effects of that narrow policy which may prompt some to aim at serving their own particular connections in ways prejudicial to the general interest, or injurious to other parts of the state—Nor do we wish that the due exercise of these powers and prerogatives should be cramped or discouraged; but that they be exerted with all freedom and firmness for the good of the people, whenever it shall be needful. It is, we doubt not, his sincere aim to improve those talents with which GOD has distinguished him, in promoting the true interest of the Commonwealth, and of the United States.—May he have the sublime satisfaction of seeing the accomplishment of his wishes, and the success of his endeavours, to serve his generation.—And the honorable COUNCIL will, we trust, be always ready to assist and co-operate in these arduous and important services, with their wise, upright, and faithful advice.

The honorable SENATORS and REPRESENTATIVES of the Commonwealth, who sustain and exercise so great a share of its authority, and in whom the people repose so much confidence, will not take it amiss to be reminded of the expectations and just claims of the State, that its interests be faithfully attended to and pursued by them, not only in the elections of this day, but in all other matters on which they may afterwards have occasion to act. Their views will be as extensive as the field of service they have before them; and not only the interests of their particular constituents, but that of the whole Commonwealth, yea, of the whole United States, will be duly regarded in their deliberations and resolves—liberality of sentiment, love to their country, a truly public spirit, with untainted, unshaken integrity, will give dignity to their proceedings, and throw light upon their paths: whether they consider themselves as the ministers of God, or the trustees of the people, they can no otherwise support the dignity of their character, or answer the just expectations of God and man, than by a faithful discharge of the duties of their station; nor should it be forgotten that all mankind of whatever rank, must another day stand before an impartial tribunal, where an account will be taken how every talent has been improved, and a recompence will be adjudged to everyone according as his work shall be. Happy then will he be beyond expression, who has maintained his integrity in a corrupt and ensnaring world; who has kept “a conscience void of offence towards GOD and towards man;” who can hold up his face before the Judge and say, “Remember, O Lord, how I have walked before thee in truth, and with a perfect heart;” and who will receive from him an answer of acquittance and approbation, “Well done good and faithful servant, enter into the joy of thy Lord.”

Will this grave and venerable audience bear with me while AI add one reflection of general concernment;–that if we would enjoy true liberty, we must not only maintain our civil privileges, and guard against a licentious and malicious abuse of them, but it is above all things necessary that we be delivered by GOD’s special grace from the bondage of guilt, and the slavery and service of sin and Satan, and that we be called effectually to the spiritual freedom of the children of GOD. Little reason shall we have to boast of liberty, or bless ourselves in our external privileges, if we are the ignominious servants of corruption. This spiritual liberty, Christ has obtained for all his true disciples: and it can no otherwise be enjoyed by any of us, than by taking his yoke upon us, learning of him, and continuing in his word”—Then shall “we know the truth, and the truth shall make us free indeed.” It is the true Christian alone who is the LORD’S FREE MAN, and a denizon of the new Jerusalem. An honor and privilege to which we cannot maintain our claim, unless we realize our profession of Christianity, by serving the Lord Christ with all good fidelity, and serving one another in love. Be this the object of our greatest care and ambition. We may then with hope and earnest expectation, wait for the day of our complete redemption. The GRAND JUBILEE will at length be proclaimed by the sound of the Arch-Angel’s trumpet, which will call the sons and heirs of GOD to the CONSUMMATE LIBERTY of his heavenly kingdom, and induce them to the inheritance incorruptible, undefiled, and that fadeth not away, reserved for them.

May this be the lot of us all, through the grace of GOD our Saviour.

Endnotes

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!