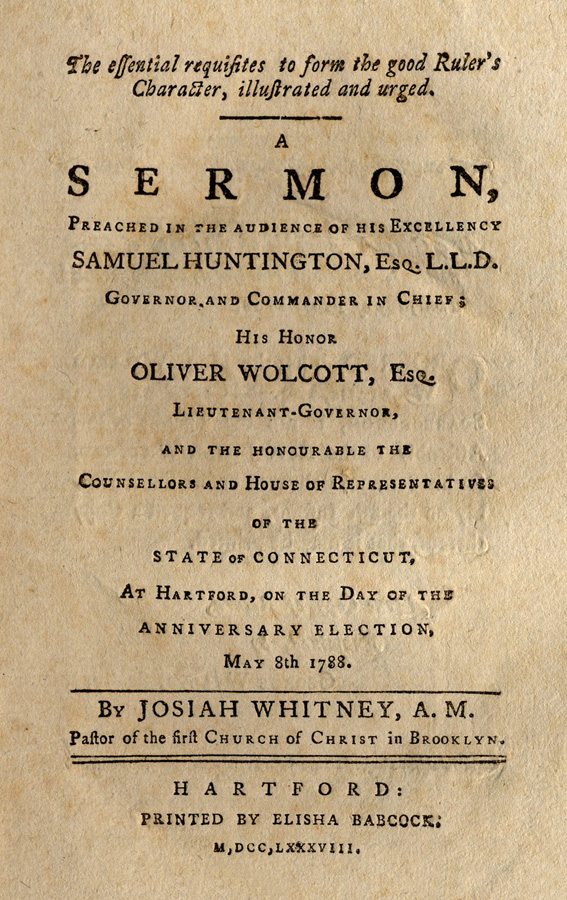

Josiah Whitney (1731-1824) preached this sermon in Connecticut on May 8, 1788.

Character, illustrated and urged.

A

S E R M O N,

Preached in the Audience of His Excellency

SAMUEL HUNTINGTON, Esq. L.L.D.

Governor and Commander in Chief;

His Honor

OLIVER WOLCOTT, Esq.

Lieutenant-Governor,

And the Honourable The

Counsellors and House of Representatives

Of the

STATE of CONNECTICUT,

At Hartford, on the Day of the

ANNIVERSARY ELECTION,

May 8th 1788.

By JOSIAH WHITNEY, A. M.

Pastor of the first Church of Christ in Brooklyn.

At a General Assembly of the State of Connecticut, holden at Hartford, on the second Thursday, of May, 1788.

ORDERED, That the Hon. William Williams, Esq. and Capt. Ebenezer Scarborough, return the Thanks of this Assembly to the Rev. Josiah Whitney, for his Sermon, delivered before the Assembly on the 8th Instant, and request a Copy thereof, that it may be printed.

A true Copy of Record,

Examined, by

George Wyllys, Sec’ry.

EXODUS, xviii. 21.

Thou shalt provide out of all the people, able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating covetousness; and place such over them.

THAT there is a living, intelligent author of universal nature, a Being called God, is a truth, which shines gloriously in the splendor of the sun — vegitates in every plant — lives in every animal, and diffuses itself throughout all nature.

That this glorious Being does according to his will, in the army of heaven, and among the inhabitants of the earth; and that his dominion is absolute, yet wise and reasonable, are also truths agreeable both to natural and revealed religion.

Absolute dominion, doing according to will and pleasure belongs only to him.

Men are not fit for it. When any have assumed it, their government has ordinarily soon become tyrannical and intolerable.

The stock of corruption in men, discovers itself as soon as there are objects to call it forth: hence none ought to be trusted with absolute power, because it gives vicious inclinations their full play, which before were cramped, and confined within narrow bounds.

Men do not mistrust themselves, because they are ignorant of what is in them.

Many who would say in a private station as Hazael did; What is thy servant a dog, that he should do this great thing? Yet like him, have done the very thing when raised to sovereignty, which before they were shocked with the tho’ts of.

There is but one Being in the universe fit for absolute rule: This one is God, in whom all perfections to meet as to form the most perfect character.

Though he is an absolute sovereign, yet his perfections prescribe the measures of his providence, so as most to promote the welfare and happiness of his creatures.

In his providential government, there is a great variety, so great that we cannot fully comprehend it, nor reduce it to rules and measures.

Hence some who suppose it a reflection on their understandings, not to be able to solve all difficulties, and account for everything, are ready to think, that the course of things is without a wise, intelligent direction.

But wiser are they, who when they feel their inability, to investigate some of the ways of Providence, believe that all are guided and issued by a divine hand.

Often when particular events take place, we cannot at first tell, whether they are the effects of the favour, or displeasure of the world’s great Ruler: Time, the great expositer of events can only satisfy us—Nay perhaps we never shall have satisfaction as to some: Yet from a belief of a supreme providential guidance, we rest assured that things are ordered, or permitted in such a manner, as that in the issue, all will see and own God to be an infinitely wise, just and good governor.

Striking instances there are in every age, of a superintending Providence: human affairs are conducted thereby to their proper periods; all which to minds enlightened and enlarged from on high, are full of harmony and beauty.

That God influences and directs human affairs, is most evident from the sacred writings; these declare, That the kingdom is the Lord’s—That he is the governor among the nations—That he judges the people righteously, and governs the nations upon earth.—The living may know that the MOST HIGH ruleth in the kingdom of men, and giveth it to whomsoever he will.—The heavens do rule. But how does God govern the world?—By instruments? Or by his own immediate influence? It may be a sufficient answer, to say, that though the scriptures just quoted speak of none but God, as governing the world, and though he needs not the aid of any of his creatures, yet to keep them busy and active, he has assigned them work, according to the talents given them. Some he wills should move in higher, and others in lower spheres—Some are to govern; others are to be governed. He raised up Moses and Aaron to give law to Israel—lead them out of Egypt, and guide them towards the land of promise. This indeed is attributed to God, but not without the instrumentality of these his dignified servants. Thou leadest thy people like a flock, by the hand of Moses and Aaron.

Moses, in our text was directed by his father-in-law, the priest, or prince of Midian, to appoint some under him, to be rulers over the people. Should it be said this was not divine, but human counsel, therefore not obligatory: it may pertinently be replied, that it was counsel which probably wanted not a divine sanction. Jethro was sensible that God’s approbation was necessary, in order to Moses’s following his advice; therefore said, If thou shalt do this thing, and God command thee so. The government the Israelites were under, was a Theocracy; and it cannot be reasonably, supposed that Moses would have made so considerable an alteration in it, without divine leave. No doubt God directed him to follow the advice. Nay, may we not add, that it is advice so evidently reasonable, that there lies an appeal to common sense, that it must be agreeable to the will of God.

In our text we have several requisites, necessary to from the character of good magistrates. These will be distinctly considered, after premising a few things, which it is hoped, will be neither foreign to the subject, nor unacceptable to the audience.

Society is necessary, to the comfortable subsistence of mankind, in the present state.

Man is evidently formed for society. When God made the first man, he saw it was not good for him to be alone; therefore made an helpmeet for him. He formed him for society, and disposed him to enter into it.

Should we suppose one placed in Paradise, where were all outward good things, in the greatest variety and plenty, but without social intercourse with his fellow creatures—could he be happy? No, misery would be his portion.

Man alone is insufficient for his happiness—Alone, he is liable to innumerable evils, which he can neither prevent nor redress—full of wants, which he cannot supply.

Hence may be argued, the expediency and necessity of uniting in society, for mutual delight, help and defense.

To speak in the language of inspiration—Two are better than one, because they have a good reward for their labour; if they fall, one will lift up his fellow: But woe to him that is alone when he falleth; for he hath not another to lift him up. If one prevail against him, two shall withstand him, and a threefold cord is not easily broken. Mankind in every age have been so sensible of the necessity of civil combinations, that they have formed kingdoms, commonwealths, counties, towns and the like, for their mutual convenience, and for the preservation of their lives, liberties and properties.

Let it be further premised, that civil government is absolutely necessary to the support and well being of society.

As society is necessary to the well being of mankind; so government is no less necessary to the support of society. Nay, good government is the very life and soul of society.

Should a number lie together without government, and every one do what is right in his own eyes, what must the consequence be in such a lapsed, disordered world as this? Why, they would soon prey upon, and devour each other. Neither life nor property could be secure. The earth would be filled with violence. Rather would a considerate person fly to the wilderness, where he might be in safety, though alone, than remain with sons of rapine and violence.

Not a few of mankind are impatient under the restraints of government: They abhor it and the necessary expenses for its support. They ardently wish to be rid of both.

Wickedness, shocking to relate, prevailed in Israel when there was no government there, and everyone did that which seemed good to him. So would it be with others, left destitute of government as they were. They would soon disband and crumble to pieces.

It is sad to have a bad government, but a government in some, nay many respects bad, is better than none. It is impossible for things to go well where there is none.

Hence, we ought further to premise, that it is the will of God, that some form of civil government should be established among mankind.

What the particular form shall be, whether monarchical, republican, or aristocratical, he has not told us.

Nations or states are left to choose and adopt such as are most agreeable to their genius and circumstances.

Some natural rights are to be given up into the hands of one, or more, for the preservation of the rest.

One form may be best for one people, and a different one for another. In general, that ought to have the preference, which best secures the lives, liberties, and properties of men.

But some form, God wills every people should have to promote, and establish the interest of society, which is the great, and sole end of government.

His will it is also, that there should be some persons vested with authority, and placed over a people. And when properly designated to places of trust, and confidence, they are to be considered as ordained of God to their office, they receive not their commission immediately from him, but mediately. They who have the right of electing them to places of rule, and vesting them with civil power, are the instruments by which God conveys the power to them; and when they are thus vested with it, they are his ministers, and are to be acknowledged as such, as long as they do his will, and well discharge the duties of their place. While they do so they are entitled to respect, and should be obeyed.

But should they cease to be ministers of God for good — should they do evil, neglect the public interest, and have no higher, better object than the gratification of pride, ambition, and selfish regard, then the obligation upon people to respect, and obey them, also ceases.

Indeed no small degree of implicit confidence ought to be placed in rulers, a trust being committed to them, implies it.

They who call them to places of trust, should consider them as fallible, liable to do wrong in some instances. Errors they expect will be found in their administration, because these attend the best; hence they should make proper allowances for human frailty. They must be more than men, who err not. Judicious persons consider unreasonable jealousy of rulers, as mean and mischievous: therefore carefully guard against it themselves, and use their influence that others might not be troubled with this evil disease, which makes all under its dominion cruel as the grave.

But should rulers abuse their power and authority, turn oppressors and tyrants—Should they subvert the public welfare; then their right to command ceases: And it is not only lawful to oppose them, but depose them.

No government is to be submitted to, at the expence of that, which is the sole end of all government, viz. the common good and safety of society. Neither reason nor religion require submission to those who subvert this end: they ought to be discarded and hissed out of their places.

The title ministers of God, only belongs to them while they do the will of God, by exercising a just and reasonable authority, and ruling for the good of men.

These remarks are agreeable to reason, and revelation.

It might be affrontive to this respectable, enlightened audience, to intimate a suspicion, that they disbelieve them, or consume the time in a labored proof of things so level to common sense.

The requisites to form the character of good rulers, mentioned in our text, will now be attended to.

Moses was advised to provide out of all the people, able men, for rulers.

Ability is an essential requisite in the character of good rulers. “Able men, i.e. as a learned expositor says, men able to endure labour;–or men who are not needy, but rich and wealthy;–or men of parts;–or men of courage; for it may refer to any of these, especially the last, such as did not fear potent persons, but God alone.” According to this, they should be men of such health and strength as to be capable of bearing the burdens and fatigues of their office.—They should be men of so much interest or wealth, as shall raise them above the temptation of transgressing for a piece of bread.—Men of parts, of such natural and acquired accomplishments, as to understand well the constitution and laws of their country; as well as the duties of the place to which they are raised. The want of these would expose them to the artifices of party tools, and render them dupes to men of intrigue. Meanness of character, strangely lessens the dignity of rulers.

As ability which respects the faculty is necessary, so is courage, the proper and vigorous application of it to public duties.—Without this the best abilities will be useless. Rulers who know not their duty, or who have not resolution enough to do it well, will never have that respect, which is paid to well exercised authority—they will be despised by the giddy and thoughtless, while the reflecting good citizen, will drop a tear over prostrate authority, knowing that the consequence of its being trampled upon, will be faction, and every evil work, all which may be presented by rulers, who know their duty, and with a steady even hand dare to do it.

Thus essential is ability, to persons clothed with authority. Yet unless it is well directed, it may be injurious to society.

Therefore that able men may be useful men, our text nextly directs, that they should be such as fear God, i.e. religious persons.

Religion is often expressed in the sacred writings, by some eminent grace, or exercise of it, either by faith in God — or by the love of God — or by the fear of God, as in our text and many other places. Such as fear God in the sense of our text, are men truly religious; who make a profession of religion, and pay a practical regard to its laws and duties.

That rulers should fear God, is evident from scripture. — The man who was raised up on high, the anointed of the God of Jacob, and the sweet psalmist of Israel, with an inspired soul tells us, what God said to him.—The God of Israel said, the rock of Israel spake unto me, he that ruleth over men must be just, ruling in the fear of God.

Jehoshaphat, a pious king gave the following charge to persons, who were designated to places of trust, Take heed what ye do, for ye judge not for man, but for the Lord; wherefore let the fear of God be before you.—Nehemiah, a devout governor gave Hananiah charge over Jerusalem, because he was a faithful man, and feared God above many. These things which were written aforetime, were written for our learning, that we should have our eyes upon men of religion, in the choice of rulers.

We cannot find in the Bible, a ruler characterized as good, but who shewed a regard to God, and the things of God.

We cannot certainly determine who are truly religious, the internal character of others is out of our sight. But they who profess religion, and are visibly governed by its laws, are to be treated and confided in as religious. Rulers never should be ashamed of honouring God, by an explicit dedication of themselves to him, and by a personal and constant attendance upon his public worship, and ordinances.—Can they who do not thus honour God, reasonably expect to be raised to places of trust?—or if raised thereto, can they with equal reason expect to be honoured, and obeyed by a religious people, as religious rulers can? I trow not.

Good natural abilities, improved, and polished by education, and rightly directed, make persons publicly and extensively useful; but would not these enlarged, and aided by religious motives, make them much more so?

Irreligious rulers are not so likely to be extensively useful, as the religious—The examples of the latter will have an happier influence upon mankind,–Even their public devotions, may not only be acts of homage to the Deity, but of utility to men, as examples of piety.

Dominion is not founded in grace, nor is every religious man fit for a ruler; yet such a man, (other things being equal) is better qualified for public trust, than the irreligious.

The religion which rulers should have, and by which their lives and conduct should be governed, is the religion of Jesus, which eminently teaches the fear of God.

The gospel of Christ invites all to behold him, seated on the right hand of the majesty on high, exalted far above principalities and powers, and to believe that he will come the second time, to judge the world in righteousness. The government is on his shoulder—dominion and fear are with him—His voice is full of majesty to the rulers of this world—Be wise now,–be instructed—kiss the son, lest he be angry—serve the Lord with fear.

The temper which his religion recommends, wrought in the soul, by the divine spirit, restores it, to its primitive rectitude—directs its actions to the best ends—and extends its views, far beyond the limits of time, even, to the city which hath foundations whose builder and maker is God.

This discovered in rulers, demands reverence to their persons—attention to their counsels—and obedience to their laws.

Happy are such rulers, and happy they who are under their rule. When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice.

The next requisite is truth, men of truth, i.e. honest upright men, above the meanness of deceit themselves, and careful to detect, and punish it in others—their words may be taken and relied upon with unsuspecting confidence—they neither violate truth by their words nor actions; their words are the true interpreters of their minds.—They punctually perform every private, and official engagement, unless unavoidably prevented, as may sometimes be the case.—The public faith they consider as sacred, and they mean to maintain it, notwithstanding the menaces of the mighty, or the murmurings of the multitude.—They abhor artifice and dissimilation—ambiguity in their discourse, whereby others might be imposed upon, they carefully avoid.

When called to judge in doubtful matters, they diligently search out the cause which at first they knew not, and having found the truth, are resolved to support it.

The last requisite to form the character of good rulers, mentioned in our text, is hating covetousness.

Which means a noble, and generous contempt of the world, and intimates that rulers should “not be greedy of money” but abhor bribery, and every dirty method of gain.

Covetousness, is an ill-looking vice, odious in itself, and pernicious in its effects. No vice perhaps more eradicates every virtuous, and social quality.

When it leads to riches, for no other end, than to look upon them, or to answer the demands of luxury, in both cases the true end of riches is defeated, and the consequence is, a forfeiture of integrity.—It leads the rich to oppress—the poor to great and petty larceny,–It hardens the parent against his offspring, makes the master cruel to his servant, and disturbes the peace of families, and communities.

A person under its dominion, is a stranger to the fervours, and pleasures of devotion, and to aspirations for Heaven, its refined, exalted delights, he has no taste for; if he was there, he would feel no joy, unless he should find that figurative description of the place literally true. The street of the city was pure gold, and could make the same use of gold there, as he has here.

Rulers under the dominion of this vice, will be mischievous to the State, by frustrating the measures which ought to be taken for its benefit, and turning them to their private emolument.

Avarice, where it is a ruling principle, silences the voice of reason, religion, honour, and public spirit; and where their voice is not heard, what effectual check can there be upon the greedy great, to control their unbounded insatiable desire of gain?—If the place they are in is lucrative, they are resolved to make the most of it, though the public might be greatly injured.

Men who hate not covetousness, are not fit for rulers, for their love of money will expose them to bribery, and to the violation of the sacred obligations they are under to fidelity.

They, whose god is either a golden, or silver, or, which is worse, a paper one, will sacrifice the public interest at the shrine of this sordid deity.

Should they be prevented enriching themselves at the public cost, by the vigilance of others, the disappointment might lead them to meditate mischief; for disappointed avarice, kindles faction. Wants, fears, hopes, and wishes terminating in selfish regard, at once check the efforts of generous public principle.

Avarice, enervates the force of government, and frustrates the most patriotic measures.

Public spirit, a liberal generous temper, springing from benevolence, stands opposed to this vice. They who have the former, hate the latter.

Though their charity begins at home, yet it ends not there, as it does in the avaricious. They wish well to all, and according to their abilities and opportunities, do good. They are faithful in things committed to their trust, rejoice in others prosperity, and happiness—embrace all opportunities to promote the public interest, and seek not their own profit, to the detriment of the public.

They hate covetousness.

The character formed by these requisites, tells civil rulers what theirs should be, and must be, to answer the end of their advancement.

Government will be poorly administered by rulers, who are destitute of these requisites. It cannot be expected that things will go well, when persons of vicious principles, and loose morals are in authority. If they are unfaithful to God, and their own souls, will they probably be faithful to the public? Every friend of virtue says no. They want something sufficient to control their lusts. Without the aids of religion, and virtue their best motives will be feeble, and inconstant.

Devout acknowledgements are God’s due, for the institution of civil government.

Some may consider it as a burden, rather than a blessing, as the invention of the ambitious, to raise themselves to the honors and profits of the world; and not as the institution of God, for the good of all—They must be wrong—for government under God, is the guard, and security of our peace, religion, lives, and properties; nay, of everything in this world, for which it is worthwhile to live in it.

Hence, submission to good government, and good rulers, is the duty of a people.

Government cannot exist, nor its advantages be felt, without proper submission, proper submission I say, not absolute, unlimited subjection, for this is fit for brutes only, not for men.

The people of this State, have an excellent form of government, and have been favoured with a succession of rulers, in whom the preceding qualification, have been eminently exemplified. Perhaps no ancient, nor modern State, in these respects has been happier.

Names, distinguished for ability, piety, and integrity grace the annals of our State. And it affords no small pleasure to believe, that Gentlemen in general of like complexion, at present fill the legislative and executive departments. And it is devoutly wished, that such may be the character of those, who may be either continued in office, or a new called thereto this day, by the suffrages of the freemen.—And also, that in future elections, persons of the same character may be the objects of their choice.

Our remaining a happy flourishing people, depends upon our having such rulers.

The discourse turns into addresses usual on this Great Anniversary occasion.

Custom, and decency, lead me in the first place, respectfully to address Governor Huntington, who, by divine providence is placed in the first chair of government.

May it please your Excellency,

As your command has brought me to perform the present service; you will allow me to put you in remembrance of the requisites, which form the good ruler’s character, though you have long known them, and are established in the present truth.

Your gradual rise on the scale of promotion, till you received the highest tokens of respect, and honor, in the power of the State to bestow, shews the public opinion of your ability, and integrity; which tokens you will be pleased to accept, as testimonials of their esteem, and gratitude, for your prudent, upright conduct, at the council-board, and on the seat of justice—For your patriotic conduct, in the federal council of the States, very especially at that most critical era, when the immortal act passed, which constitutes the Independence of these sovereign States—By which a Nation was literally born in a day, and your name, and the names of the rest of that august body, will be transmitted with applause to posterity—and for discharging afterwards, with dignity, and to universal approbation, the office of President of Congress.

Since you have been our first magistrate, you have been acceptable to the multitude of your brethren. And should you again be called to be so, we trust it will be your unremitted, unwearied care, to seek and promote the welfare of this people.

You cannot be insensible Sir, that they who have entrusted you, with this large portion of authority, have a right to expect this.

We doubt not the rectitude of your intentions, nor call in question the sincerity of your desires, to discharge the trust reposed in you, to the acceptance of this people, and what is ore, to the acceptance of God, before whom, you as well as we must stand, and be judged.— The fear of God, or religion (which we trust has a commanding influence upon your heart, and life) will best prepare you for every duty—afford the most effectual aids in doing it—diminish fears in times of danger—and raise you above the frowns and flatteries of time.

We can wish your Excellency no greater felicity, than the union of fervent piety, with a strong public affection; these united, and aiding each other, will make you eminently useful, afford peace in your own breast, such peace as the world cannot give, nor take away—administer the best supports in the article of death—and accompany you to the General Assembly, and the church of the first-born, which are written in Heaven, into which illustrious assembly, may an entrance be administered unto you abundantly, after you have served your generation, by the will of God. Amen.

The discourse nextly turns to Honor Lieutenant Governor Wolcott, the honourable Counsellors, and house of Representatives.

Honored, and much respected Gentlemen.

We esteem ourselves happy in having rulers, and Representatives, who proceed from the midst of us; and will therefore more naturally care for our State.

Your time, abilities, and authority, by your acceptance of public trusts, are consecrated to the community, and cannot without manifest injustice, be withheld therefrom.—And by your official oaths, you will feel an additional obligation, to promote the public welfare.—No solicitude to promote it, would be to violate your sacred honour, which you have pledged, and to incur the displeasure of God, unto whom you have lift up your hands.

When your attention in past sessions, has been called to national and State matters, difficulties neither few, nor small (by reason of the inefficiency of the consideration) have met you. It is hoped that future ones may not be so many, nor so formidable, if that Constitution of Government should be established, which the honourable convention of the States have recommended. The wisest and bestof our citizens, esteem this Constitution, though not perfect, yet as very replete, with temperate, energetic, political wisdom—They rejoice that seven of the States have accepted it, and earnestly wish that it may soon have the approbation of ALL—at least two more to complete the number required for its establishment.

Could its establishment, have been announced by the Chaplin of the day, with singular pleasure he would have congratulated your honours,–this respectable assembly, his fellow citizens, and countrymen, upon the auspicious event.—But though he cannot, yet is pleased with the prospect, that the Preacher on the next anniversary election, may have the satisfaction of doing it.

Meanwhile, may you Gentlemen, find no insuperable embarrassments, but be able to discover, and adopt adequate remedies, for every complaint.

To restore and maintain the public faith, and credit in pecuniary matters—do justly to creditors—promote peace and order—suppress vice—reprove and reform Sabbath-breakers, and the neglecters of public worship-=-patronize the interest of learning—and countenance religion,– the fear of the Lord, are things, most important, and will employ your thoughts, after the elections of this day are over.

Arise Fathers, these things belong to you.—The virtuous citizens of the State will be with you; and what is more, God will be with you—Be of good courage and do them.

The examples of rulers, have great influence upon the manners of the people.

We expect, and have a right to expect, religious ones from you, these will more effectually recommend, and enforce the practice of religion, than any laws you can make, these, beheld not only in your public administrations, but also in private life, will be the most forcible laws—the most effectual means of persuading others to fear God, and keep his commandments.

Our text not only requires, that you should be able men, but also such as fear God.

The best preaching will ordinarily be but to little purpose, if rulers in general by their practice say, the fear of God is not before their eyes. Gentlemen, we are persuaded better things of you, and things that accompany salvation, though we thus speak. Under the influential guidance of that wisdom, which is from above, may you shew yourselves able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating covetousness; and may you receive the reward of faithful servants, when removed from the present sphere, and verge of mortality. Amen.

My fathers, and brethren of the Clergy, will candidly accept a few words, addressed to them, if fitly spoken.

Reverend Sirs,

Our office is important, its duties difficult, who is sufficient for these things? Aided by our Divine Master, our ministry will not be in vain; his grace therefore, let us devoutly solicit, that we may be serviceable to mankind.

Countenanced by civil rulers, we may successfully recommend obedience to lawful authority—the observance of the wholesome, and necessary laws of the State—reprove vice and immorality—shew the ruinous tendency of discontent and faction—and the salutary effects of leading quiet and peaceable lives in all godliness, and honesty.—If at proper times we judiciously treat these subjects, and influence others, to pay a practical regard to them, we shall be essentially useful to the commonwealth.

Our profession has been treated with contempt, and insult.

An Hume felicitated his times, and boasted, that “the clergy had lost their influence”—But ought it ever to be a matter of boast, that a learned virtuous clergy have lost their influence?—May not one, though of the order, be allowed boldly, yet decently to affirm, that when the clergy, and that religion which they faithfully preach, have been most honoured, and respected by a nation, then things went best among them, and they were most honoured, and respected by nations around them.

This State from its beginning has been happy under the influence of Christian Bishops of the above complexion; and does it not much concern us, the present Bishops of the churches, that we are good ministers of Jesus Christ? Certainly it does. Convinced of this, let it be our invariable aim, to promote the civil interests of the State, in the ways just mentioned.

But we are not to stop here—the spiritual and eternal good of those committed to our charge, should most of all engage our attention, and employ our time and talents—We are to declare all the counsel of God, respecting the recovery of our sinful race, from the ruins of the apostacy, through a Glorious Christ. To testify repentance towards God, faith towards our Lord Jesus Christ—to explain, and urge that holiness, without which no man shall see the Lord.—To affirm constantly the connection between the means of religion, and its existence—This derogates not from the grace of God, for his grace is not more exalted by precluding all beneficial tendency of means, than by allowing it, since the means, and their operation are from him. Means are appointed; but if of no service, why were they appointed?

In our preaching let us keep close to the word of life, and declare its truths, in their native purity, and simplicity.

Abstract reasonings, metaphysical speculations may amuse some, but cannot profit any, like the plain, easy, and simple truths of Christianity; these, will afford solid, lasting comfort to devout souls hovering on the verge of life, while those, in this solemn hour, will pass away as a vision of the night—In a word, let us preach the essential fundamental truths of the gospel, the unsearchable riches of Christ, and tell all, both high and low, rulers, and ruled, that unless they repent, and believe, and follow after holiness they cannot be saved.

The time to fulfill our ministry is short, we like the priests of old, are not suffered to continue by reason of death—presently, we know not how soon, we must go the way whence we shall not return—the way which our departed fathers, and brethren have gone—the way which those truly respectable, and eminent ministers of Christ 1 have gone, who have died since the last Election.

May we be diligent, and faithful, that we may be found in peace, without spot, and blameless at the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ. Amen.

An address to the Assembly at large closes the discourse.

Men, Brethren, and Fathers.

The requisites to form the character of good rulers, have been laid before you, let them have place in your memories, that those persons may have your suffrages, in future elections, who are able men, such as fear God, men of truth, hating covetousness. They who are deficient in these, or are vicious, and immoral, are at once to be reprobated. One of these requisites, viz. the fear of God, or religion is the one thing needful for everyone, of whatever age, or character. Happiness in time, and through eternity depends upon it.—This, we neither should have mentioned, nor urged had we meant, to court the applause of those, who value themselves as being too polite, to be religious.—This is their language—“To suppose persons of fashion, swayed in their conduct, by a regard to religion, is an affront to the delicacy, and refinements of a modest taste”—Hence, they deride the ordinances of Heaven—the day set apart by the law of God, and their country, for worshipping the deity is treated as a vulgar, obsolete institution—should you recommend to them, that family devotion which began the mornings, and concluded the evenings of their pious ancestors, you would become the objects of their pity, if not contempt. Had our object been the ratification of these persons, we must have apologized for the rudeness, of even hinting at religion as necessary, for anybody. But knowing we must speak not as pleasing men, but God who trieth our hearts, we are bold in asserting, the necessity of religion, and in saying, that such modest ones ought never to be raised to posts of honour, and trust—nay, should any after being raised thereto, be found such, let them speedily be removed as utterly unworthy the public confidence, and left to herd with their like, in irreligion and vice.

Should indifference, as to the character of rulers ever become fashionable, or the preference given those who cast off the fear of God—make light of Christ—his religion—laws and ordinances—that it would become those who speak in the name of the Lord, on such occasions as this especially, to urge with pathos, the necessity of rulers having the second requisite contained in our text—And they would be faulty if they did not.

Excellent, my fellow-citizens is the Constitution of our State, with a great sum it was obtained by our worthy Forefathers, and at the expense of much blood, and treasure it has been defended, and preserved—The footsteps of a kind, almighty Providence are to be traced, in uniting, and defending these States, when involved in the horrors of war,–raising them to freedom, and independence, restoring Peace, and hitherto continuing it—and also in the prospect, of soon having an energetic government established. May our gratitude for the great, and good things which have been done for us, be evidenced by a wise, and discreet improvement of our constitutional privileges.

The right of electing rulers and representatives, is ours. We cannot reasonably wish to elect them oftener than we do.

When called to elect representatives, let men be the objects of our choice, who have the requisites recommended in our text: They who have them, will not need the instructions of their constituents, to regulate their votes in General Assembly.

By a proper use of the right of electing rulers and representatives, we may obtain the redress of any real grievance.

Hence recurring to arms and staining our hands with blood, is quite needless—Nay, it is a crime which deserves the severest vengeance, in the power of a State to inflict.

The last year’s outrages opposition to government, in a neighbouring commonwealth, viewed in its nature, and tendencies, should lead us to abhor faction, and its promoters, and abetters. Whether the lenity of government towards the leaders of that rebellion, is consistent with good policy, is a question, which by and by will be faithfully answered by Time, the best expositor of events.

The disappointed, and restless, persons of broken fortunes, and characters, will at times excite, and foment disturbances; and under the guise of patriotism, call for the redress of pretended grievances, with a view to gratify their avarice, or ambition. These, when formed into little political clubs, and allowed to lead others, as uneasy, and mischievously inclined as themselves, are always troublers of a State, and should be treated as pests in society.

What Heaven’s will is concerning persons of this complexion, is manifest from that edict of its great ruler, to all his loyal subjects—Take us the foxes, the little foxes that spoil the vines, for our vines have tender grapes. q.d. “diligently look after these mischievous ones, take them in their early craft, check them in their beginnings, while they are yet little foxes, small whelps; knowing their craft and subtilty [artifice], windings and turnings, shifts and evasions; timely guard against them, detect their frauds, use every effort that they might be taken and kept from doing further mischief.”

Thankful, let us be for our privileges, and careful to cultivate and cherish the virtues of civil life—Let us encourage the hearts of rulers, and strengthen their hands, by appearing in their defence and for their support, while they shew themselves ministers of God for good to us.

By industry and frugality let us aim to improve what we are already possessed of to the best advantage, that we may keep what we already have, as well as acquire more. Aided by these, agriculture, manufactures, and traffick will flourish; and we shall be able in due time, to have the necessaries and conveniences of life in such plenty and variety, as to render the importation of them from foreign nations, less necessary.

Diligence in our callings, retrenching unnecessary expenses—living within, and not beyond our incomes—avoiding extravagance, and dissipation, will make us an opulent happy people.

All whether high or low, rich or poor, have work to do. Let none eat the bread of idleness.

Let not America’s daughters, however affluent their circumstances may be, think it disreputable, to seek wool and flax, and work willingly with their hands, by applying them to the spindle, or with them holding the distaff. And to enforce this, let it be remembered that no less a woman than the mother of king Lemuel did so, or recommend it.

Let us, respected hearers, do all the good we are capable of doing. A large reward awaits all who do much good.

The connection between time, and eternity, is real, and important.—The intellectual endowments, and moral pursuits of those of our race, who partake of the rest which remains for the people of God, are doubtless, analogous to those they had in this world.—The measure of their bliss there, is apportioned to their improvements in virtue here—pleasing thoughts these, to contemplative, devout minds; and should raise desires for the sublimest knowledge, in the improvement of intellectual powers; and serve to regulate moral pursuits, by the strictest virtue: in doing so, we may with reason expect capacities there, wonderfully enlarged, and fitted to operate with the utmost facility, in most extensive spheres.

The joys of Heaven, consist not in epicurean indolence, nor stoical apathy, nor enthusiastic raptures, nor in the sensual gratifications of the Koran—But in conformity to the image of God—doing his will, and enjoying him.

The rewards of eternity, were of old much confined by ethnic pride, or policy, to celebrate conquerors, and legislators.

But Christianity announces blessedness, to the virtuous of all nations, capacities, stations, and ages; it assures all the devout followers of the lamb of God, moving either in the higher, or lower walks of humanity, that the crown of life, shall be theirs, that in the Great Rising Day, they shall be happy in their whole persons, happy in proportion to their place, on the scale of goodness here.

But not so, shall it be with the ungodly, those who would not that Christ should reign over them—endless sorrow will be their portion.

Is the present life thus connected with the future? Does religion lead to happiness? Irreligion to misery? Then let us chuse and practice the former, and guard against the latter, that our future existence may be happy. By religion, not only our spiritual, and eternal interest will be promoted, but our temporal also; for it serves to render us useful, and ornamental members of society.

Such, let us invariably aim to be, so long as it shall please God, in whose hand our breath is, to continue us in this world.—But let us not chiefly look to the things which are seen, and are temporal: for our chief, our greatest interest lies in a better country, that is, an heavenly, to which may our souls, on the wings of faith, and contemplation often soar. While on earth, may our conversation our citizenship be in Heaven. And may we have the testimony, the first of the human race had, who went not downwards to the sky” which was this, That he pleased God. Our ambition can fly at no higher, nor better mark than the pleasing that Being, who made us, and will judge us. Though it would be presumption, to expect such a passage from earth to Heaven, as Enoch had; yet if we have a like testimony, that we please God, we may rest assured, that when our earthly tabernacles shall be dissolved, we shall find the building of God, the house not made with hands, eternal in the Heavens.

Now unto him that is able to keep us from falling, and to present us faultless before the presence of his glory, with exceeding joy; to the only wise God, our Saviour, be glory, and majesty, dominion and power, both now, and ever.

A M E N.

Endnotes

1. Rev. Mess’rs Little-Trumbull-Whittlesey-Williams.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!