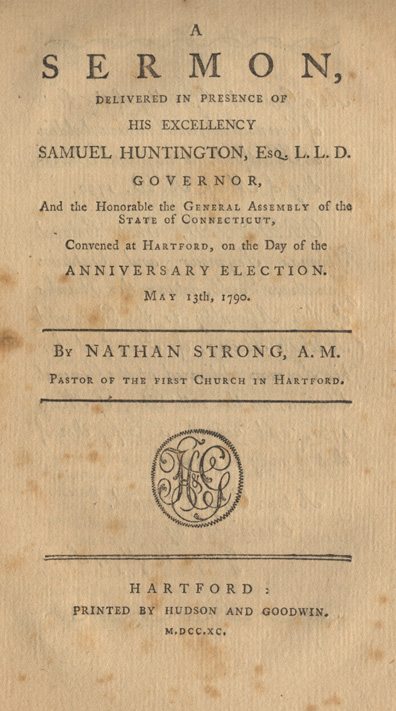

Nathan Strong (1748-1816) graduated from Yale in 1769, was ordained in 1774, and became pastor of 1st church in Hartford. He served as chaplain in the Revolutionary Army, ran the “Connecticut Evangelical Magazine” from 1800 to 1815, and was one of the founders of the Connecticut Missionary Society.

Mr. Strong’s Election Sermon.

1790

A

SERMON,

DELIVERED IN PRESENCE OF

HIS EXCELLENCY

SAMUEL HUNTINGTON, Esq. L.L.D.

GOVERNOR,

And the Honorable the General Assembly of the

State of Connecticut,

Convened at Hartford, on the Day of the

ANNIVERSARY ELECTION.

May 13th, 1790.

BY NATHAN STRONG, A.M.

Pastor of the First Church in Hartford.

HARTFORD:

PRINTED BY HUDSON AND GOODWIN.

M.DCC.XC.

At a General Assembly of the State Of Connecticut, in America, holden at Hartford, on the Second Thursday of May, A. D. 1790.

ORDERED, That Colonel Thomas Seymour and Captain Jonathan Bull, return the Thanks of this Assembly to the Reverend Nathan Strong, of Hartford, for his Sermon delivered at the General Election, on the 13th Day of May 1790, and request a Copy thereof that it may be printed.

A true Copy of Record,

Examined by

George Wyllys, Sec.

ELECTION SERMON.

ROMANS, xiii. 7, 8, 9.

Render therefore to all their dues: tribute, to whom tribute is due; custom, to whom custom; fear, to whom fear; honor to whom honor.

Owe no man anything, but to love one another: for he that loveth another hath fulfilled the law.

For this, Thou shalt not commit adultery, Thou shalt not kill, Thou shalt not steal, Thou shalt not bear false witness, Thou shalt not covet; and if there be any other commandment, it is briefly comprehended in this saying, namely, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.

This passage, which is a summary of the laws of Religion, may also be considered as a summary of those political and social duties, by which a nation is made happy. The chapter in connection is the best political dissertation that was ever penned. Without entering into a comparison of the several kinds of government, which men have erected, the writer confines himself to general truths and duties, which are necessary in all of them, are founded in the nature of society, and approved by reason and experience.

He begins the chapter with asserting the divine origin of civil government. The powers that be are ordained of God, whoever resisteth the power resisteth the ordinance of God. Infinite wisdom suffers us to chuse our own form of government, and designate the instruments by whom it shall be executed; but the ordinance is still the Lord’s, and to refuse obedience is sinning against heaven.—Nor hath any man a right to complaint, as the institution was designed for human good, and there is an easy way of reconciling our own interest with all the powers of a well regulated government. For rulers are not a terror to good works but to the evil. Wilt thou then not be afraid of the power? Dost thou desire it to be a blessing and not an evil to thee? Do that which is good and thou shalt have praise of the same. For he is the minister of God to thee for good. Wherefore ye must needs be subject, not only for wrath but conscience sake.

After asserting the divine origin and the necessity of civil government, in some of the kinds practiced by men; the Apostle recapitulates, in our text, the principal duties by which society is united, protected and made happy, and sums up his description in these words, And if there be any other commandment, it is briefly comprehended in this saying thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.—If there be any political duty, not otherwise expressly commanded, we may find it in the great law of Christian love; this law directs rulers and subjects in every possible connection, and will make them faithful in their respective places. On reviewing the connection of the chapter, it appears that the Apostle designed our text, as a collection of political maxims, by which society may be preserved, and the great end of government be promoted under whatever form or constitution it subsists: and on further attending to the same maxims, we find they are the essential laws of religion, which were early given to men as a rule of duty, and of their present and future well being. I think this is a clear proof, that religion and a well regulated civil government are subjects which cannot be separated. A good ruler or a good subject will not suffer these laws to go out of his view. Happiness is the great end designed by all social institutions; for this, the laws and duties of religion are enjoined on creatures by the wisdom of their maker; for the same end men have organized government, and defined its powers and duties; both have relation to the social capacities and enjoyments of connected minds, and aiming at the same end, must in a considerable degree procure it by the same means. So far as religion and government deviate from each other, one or the other of them deviates from the nature of men, and the effects of their social relation.

Happiness cannot subsist without love and justice, between those who are brought into connection by the supreme providence. The blessedness of a perfect world, and the perfection of divine government, are represented to us by the abundance of these virtues. We have no reason to suppose that systems of virtue or law, essentially different, are necessary for the good government of the heavenly and earthly societies; as they both aim at the same thing, the happiness of rational minds in union with each other. There is not an idea, in the world, more dangerous to society, or more debasing to civil government, that this, that it stands on a basis of human wisdom and will, apart from those great religious obligations, which direct the manner and duties of intercourse in all worlds.

Religion, or love, holiness and righteousness, the names by which it is commonly called in the sacred oracles, is the constitution and law of the supreme government, by which the Almighty is glorified, and his creatures connected in blessedness; and the nature of intelligent beings admits not a safe introduction of other principles; depart from these and we act no longer like reasonable men or like Christians.

Our apprehensions of a perfect and glorious society must be defective, as we have not the aid of experience; but in accounting to ourselves for the blessedness and stability of its orders, we always conceive the perfect exercise of religion, as a cause sufficient for the effect. If the laws of religion are sufficient to render the divine government most glorious and happy; and if the practice of religion will give a future perfection to the heavenly life, why are not the same principles and practice, the strength and safety of men’s government in this world. The Lord our God governs according to the nature of things, and his administration always ends well; and are not men, when they act for him in the temporary authorities of the world, most like to succeed, to support their own dignity, and be a blessing to others, when they adopt in their administration and act from the same principle.

A ruler needs religion much more than his unofficered brethren, to support his mind under trials, and to guard him against temptations. When the respectable citizen rises from private into public life, he must expect to exchange quietness for trouble; honor, though alluring, has its bitterness and its dangers; enemies before unknown, will rise up; the jealous will sift all his actions, and what man can be so guarded as to have all his behavior escape censure? The ambitious, thinking him in the way of their own progress, will be his enemies. To support the mind under these evils, and lead it into the exercise of prudence and patience, religion is necessary.

To hold great power and places of confidential trust is a state of temptation, which every man cannot resist, and those who are wise will not accept a call to public service, until by examination, they find in their hearts fixed principles of fidelity. A bad man may seek elevation, but it is only a good man who can bear it; many shine in adversity, which cools the appetites and unsocial passions; but to shine in prosperity; to be humane and just in the circle of a court; to be true and honorable in the treatment of all mankind; to be righteous and honest when power gives opportunity for oppressing, the assistance of fixed religious principles are certainly necessary. If religion be necessary to assist us in the common duties of life, it is more necessary where duties are multiplied and enlarged.

Political elevation is generally esteemed honorable, but it is not always attended with honor, for this depends not on the elevation itself, but on the principles and conduct of the person who is raised. What is true honor but the esteem and love of mankind on virtuous reasons? He who renders to all their dues—who preserves himself from a transgression of God’s laws, by injuring the purity, interest or reputation of others, and performs the political and brotherly duties enjoined in the command—thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself; he hath an honor which enemies cannot long stain, nor time wipe away. But a profusion of knowledge, and the glare of great abilities, without fixed principles of love to God and men, are like a song, the sounds die away and the pleasing surprise of the mind departs.

Having made these general remarks on the usefulness of religion in civil society, and in the character of one who rules men; that we may see its efficacy in the clearest manner, let us more accurately trace its nature and effects in the mind.

We are now to consider the formation of a character, which will be uniformly supported thro life, and where a steady practice evidences some habitual dispositions, that cannot be subverted by every slight temptation.

The great end of political associations is best answered where there is the most perfect union, and those principles are most essential to government, which have the greatest tendency to produce union. The interests of individuals, are by the emergencies of time thrown into many situations. We live with many others whose passions are complicated, various and pointed to their own personal ends. Every lesser district, very family, and individual in the family, hath interests of its own. If these private interests have a supreme influence the utmost evils will ensue. It is the business of government to hold the balance between them, to check the overbearing and point them to a common good, and for this it needs the assistance of some pervading social bond, and this bond can be no other than religion.

But few minds are so enlightened in the institution of nature and the supreme wisdom which formed it, as to see that a pursuit of the general good will be an eventual advancement of each man’s private good; and where there is this enlarged understanding if the heart be corrupt, the passions will rebel.

In all rational society there needs some cementing principle of the heart, by which the minds who compose it may be united, have one interest, one common good, and one happiness.

Many philosophers, and politicians of renown in their times, have enquired for this bond of union without success, and seduced by their own reasoning, have substituted art, corruption or power.

Christian love in its comprehension of virtues, is the supreme tie of social connexion. This is the same as the Apostle means, when he says –owe no man anything, but to love one another—and if there be any other command, it is briefly comprehended in this saying, thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.—He that loveth his neighbour hath fulfilled the law; he will exercise all the varieties of love as they are modified in the actions of justice, truth, integrity and beneficence; he will render to all their dues, tribute to whom tribute is due, custom to whom custom, fear to whom fear, and honor to whom honor; he will reverence the property, peace and reputation of all mankind; and by his divine love he will be made happy in doing good to others.—Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, with all thy strength and with all thy mind, and thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself, are the two greatest laws of an enlightened policy, in every community of reasonable creatures; this is religion in the heart, and the visible practice of it is that religion in life, by which a man becomes a good ruler, or a good subject, according as God is pleased to place him. These first laws of religion are as excellent for earth as for Heaven; and as good a directory in civil administration, as in Christian living.

I would not be understood that the holy scriptures are a code of civil law, nor that they superceed its necessity, nor that the religion of Christ determines the most proper constitution of nations. The divine law and gospel have in view a more comprehensive object, the government, the glory and happiness of the creation; still they embrace those moral and religious principles, in all their varieties, on which the happiness and stability of lesser societies must depend.—Public peace is the fruit of union—union is the result of Christian love and religion. When every man regards the welfare of his brother and of the whole, the political body is strong, full of energy and happiness.

These are the most permanent and safe principles on which society can be organized, and all others are liable to an easy dissolution. Power may constrain a kind of order in the state, but its very appearance is gloomy, and it is destitute of happiness. Fear which awes cannot sweeten the heart and feelings of mankind; the subject compelled to quietness by a dread of severity, at the same moment wishes revolt, and the pleasant amities of living are all denied.—The selfish passions may be variously addressed, and a system of human art constructed; but to how many casualties it is subject and how often annihilated in a moment, the history of empires is full of witness. Justice, truth, righteousness and mercy are the solid basis of empire, and these are but branches of religion or Christian love. To these permanent principles of society nothing may be opposed, and the necessity which men sometimes urge is but a delusion. All the virtues of a pious and good life, ought to be the object of national encouragement. These reconcile the heart of the subject to the welfare of the whole and of his brethren. They make a ruler the friend and father of his country; and might the heart of every citizen be inspired with these principles, the art and exercise of government would become extremely simple, and each one would be influenced by his feelings, to act in the sphere of his duty. Coercion or an artful address to the passions of different orders of men would fall into disuse, for it is only thro human degeneracy, that these subsidiary aids can produce any benefit.

I am sensible that human nature must be taken by the civil governor as he finds it, and that there is not in the world a sufficiency of true religion to effect so happy a state as is described; but still he ought not to let these great principles of society go out of view, and if he doth, will certainly injure the public.

It is not uncommon for some, on observing men’s corruption, to embrace dangerous opinions on this subject. Aiming at a wise and deep policy, they substitute collusion, intrigue, and an artful address to the passions and interests of parties, in the place of love, justice and truth. They insinuate that religion and its institutions have nothing to do with government and civil policy, and that the moral obligations which may be a fit subject for the exhortation of a clergyman, cannot be very strictly consulted by those who manage the civil interests of mankind. When any collection of people are so corrupt, that they will not bear reproof and the corrective restraint of government, that people ought to be disbanded and feel the correction of their own vices; and that which ought to be done the natural operation of things will speedily effect. Such representations as I just mentioned, may sometimes proceed wholly from corruption of heart; an ambitious man, who knows himself destitute of religious principles, must be unwilling to have their usefulness in society generally acknowledged; but very often I believe they proceed from an ignorance of human nature, and the nature of society. Tho the arts of corruption may succeed with a man for a few times, a loss of public confidence will put it out of his power to repeat them often. Let him that ruleth over men be just; ruling in the fear of the Lord, is a law of perpetual usefulness, and derives its fitness from the nature of society; indeed religion is the best bond of society, and being such is the best support of government.

Tho a distinction is made in the state, between the civil and Ecclesiastical departments, neither of them is independent of the other. Civility and the good order of political regulations are a great advantage to religion; religion and its institutions are the best aid of government, by strengthening the ruler’s hand, and making the subject faithful in his place, and obedient to the general laws.

Tho the author of our holy religion assumed no temporal authority, and gave no opinion on the several kinds of government, or the temporal jurisdictions of men; yet he established as first principles in his church, those laws which are essential to the peace of every state; on which every kind of authority must stand, which can be a blessing to the people; or which nerve the hand of government and protect the liberties of mankind. Hence we find that wherever a just understanding of Christianity hath obtained, and its duties been practiced, they have had a benign influence on the liberty of nations: And where a contrary effect hath been aided by what men called religion, as was the case in the Papal Hierarchy, it was owing to a subversion of the true principles of Christianity. A spurious superstructure was raised by the corruption of men, falsely called by the name of religion, and not calculated to refine either the affections or practice of the people, but to aid a secular power by terrifying men, while those who were first in church and state shared their spoils.

The religion of Jesus, with no weapons in its hand but those of truth and love, silently subverts oppression; makes the people regular in discharging their duties, and rulers upright and humane in their administration; and there needs no other means to subvert the tyrannies of the world, than the universal spread and practice of this religion.

When as subjects, we find that religion assists us in doing all enjoined duties, and reconciles us to the interest of the public and our neighbours, we must suppose, that it will give equal assistance to those whom God appointeth to be in authority over us; and that their manners ought to be adorned by obedience to the divine law. We feel sure that religion will guard them against temptations—lead them to a sound policy—to liberal feelings—to a paternal regard of the people, and an undaunted support of justice.

If there be not a mistake in these leading propositions, the following important conclusion must be received; that without religion no society whatever can long subsist in peace, or those who are members of it have reason to rejoice in the connexion.

The supreme will commands religion, for its usefulness to his connected creatures. He saw that by this, the minds he created would become happy, and be joined in a communion, that makes the advantage of each one, matter of joy to the whole, and the dignity and perfection of the whole, an object of delight to each individual. He saw that thus the intelligent kingdom would have one spirit, one interest and one happiness. On what other foundation can rational and useful union subsist in this world? In both cases the subjects are the same and have the same powers, faculties and capacities. Do not those persons therefore act unnaturally, and against the laws of existence, who attempt the establishment of any society on other principles beside those of religion? Are not their expectations of its permanency without reason? Have we not always found the spirit of religion our best assistance in the duties and connexions of life? Have we not found our families happy, in the same proportion, as its spirit and orders reigned in them? Or looking back on the civil state, can we recollect a single instance of public injustice, or the semblance of it, or the extraordinary prevalence of any immorality, which was not followed with great evils? The law of God and nature can never be repealed.

The conclusion extends itself still further; First, that it is the right; and Secondly, that it is the duty of civil rulers to protect religion.

First, it is their right. It is a plain maxim of reason, that the civil state is vested with all necessary powers of self-preservation. If it be lawful for mankind to combine in a political union, they have right to perpetuate the establishment; and as the passions of men are, there can be no comfortable living without such establishments. To deny civil government the right of protecting religion, and suppressing irreligion, is denying it the most essential means of self-preservation. All kinds of vice militate against the state, and religion in the modification of its virtues are its safe-guard. To organize the civil state, and appoint a number of the people to be rulers; to commit the public to their charge and make them responsible for its well-being; and then to deny them the means and power of protecting and encouraging religion, is a severe requirement. If any man accepts the charge, under this restriction he promises beyond human performance.

Secondly, It is the duty of rulers to protect and encourage religion, and of the people to assist them in doing it. The public weal is the most sacred of all earthly betrustments. Every man when called to office, hath an opportunity to refuse this care, if he thinks himself incapable, or finds that his heart is not honest enough to do it with fidelity; but when the trust is accepted, the obligations to a faithful performance are most sacred. No light causes will excuse either the civil, or religious minister of the public, for unfaithfulness in the duties of his office. The happiness of an individual is dear, and the forfeit of it more bitter than can be described; how much more dear the aggregate happiness of the public body? Entering into society, we deposit our property, lives, friends and happiness, in the hand of the public; the public recommit this trust to the care of rulers, and give them a right and power to see it inviolably preserved. If religion and its institutions be the most certain means to preserve, is it not their duty to protect and encourage virtue and piety? Or can any man be called faithful in his appointment, who hath neglected to give this encouragement, both officially and in the private example of his life? He hath had the visible dignity, but with a consciousness of unfaithfulness, can he feel honorable to himself, or be so vain as to suppose that he is respected in the hearts of the people? Under a conviction of the truth I have urged, can he look back upon himself with a peaceful conscience? The parent who hath been a fearer of the Lord, and a faithful subject and citizen, when he sees his family corrupted by such irreligion as the state ought to suppress, hath reason to complain, that his expense and allegiance have not been repayed by that guardian care, which he had a right to expect from the civil power, which alone can stop the sources and punish the instruments of corruption.

May I be suffered to suggest another serious truth. The government is the Lords; men are the instruments of providence in arranging its powers and duties, and appointing proper persons to execute them; the government is still the Lord’s. He commits his creatures to such of their brethren, as are supposed to have most wisdom and discreetness. The whole earthly state, is designed as a school of instruction, and correction to mature such virtues, as will make men perfectly happy in another life. This is one end of government, for we cannot disconnect time and eternity. This great people are placed in the hands of their rulers, by Almighty God their tender Father and Saviour. He sits supreme King and expects fidelity from all; every care and exertion that such religion be encouraged, as will secure present and eternal happiness. Could we keep alive a sense of divine things, and the connexion between this and another world, these truths would make a deep impression on all our hearts.

By commending religion to the protection of the state, and the practice of its leading characters, I do not mean to urge an intolerant and persecuting spirit, which is very different from a tender care of piety. Many differences of opinion in a land of Christian light, are concerning the non-essentials and the ritual of religion. Several of these matters, the great head of the Church when he was on earth, did not think proper to determine. Their propriety often depends on local or temporary circumstances, or on the particular construction and feelings of different minds. Such differences when conscientiously maintained, have not a dangerous effect either on the essentials of religion, or good order of the state; and government may tolerate them with safety. If we look thro the Christian sectaries, who differ in ceremonies and words, candor will perceive, that the greatest number of them unite, in the weighty matters of faith, piety, religion and justice, towards God and towards men. A diffusion of knowledge is now advancing a liberal spirit. May the Great Head of the Church hasten the period, when those who think alike, concerning a divine love, justice, faith and truth, may join their hands and hail a future meeting in Heaven, where ceremonies and modes of expression will not separate brethren. Experience hath taught, that tolerancy in these things is the most powerful means of union; and a conscientious government will find little difficulty in determining when to encourage and when coerce.

But while we speak of a liberal spirit, let not immorality and irreligion think they have a right to our tenderness. Liberality is a divine affection of the heart, a love of the truth and of men, and cannot be pleased with vice. True liberality is Christian love, and delights in God and in all the virtues he commandeth, and is most mistaken by such persons, as triumph in vice over the social obligations: If there be who speak with lightness of a most perfect and glorious providence; if there be, who think they may treat the religion of their brethren with lightness; if there be a few, either so odd or weak in their way of thinking, as not to see in our sacred books, truths most favorable to society, and a most glorious description of Almighty, his justice and goodness; if there be, who live wicked and immoral lives, they ought not to think it consistent either with the dignity or safety of the state to protect their sins. A delirious man is to be pitied, but for his sake a nation cannot change its institutions: An immoral man is a subject of our forgiveness and prayer as Christians, and of our neighbourly offices as citizens; but must not expect, that the venerable public, will suffer him to sport with the principles of their existence.

Our subject admits a variety of practical inferences, on which I may not enlarge. It instructs us all how to be good citizens: Every man is a member in the political body; and every member hath a place in which it may be useful. If any are not useful, it is their fault; for divine wisdom hath so organized the body, there is a place, a business and a duty for all. The man who doth his duty, be his service what it may, deserves well of the state. No order, profession or employment, may say to another, there is no need of thee. All will do well if they respect the great principles of religion, if their hearts possess divine love, and their practice be in obedience to the law of God; and without these a man’s character will be defective, whether he move in a high sphere, or hath a humble place in the state. Religion will make us contented with such place and employment as providence appointeth, and authorize us to think of ourselves we are not useless. The want of religion, if it doth not make a person entirely useless, yet in a great measure destroys him to mankind; and our rising admiration of his useful accomplishments, dissolves in tears of sorrow for degenerate human nature.

Our subject reproves all those vices injurious to society, and none is more so than party spirit. Partial affection for local districts and their interests, must breed opposition, and the general good will be forgotten in interested altercation. But of all party intrigue, that is the most open insult on the dignity of a free state, and most threatening to its happiness, when offices are bartered for emolument, and dignities divided by private influence. Such things religion forbids, and decency with a sigh turns her face from the scene.

Religion forbids, and when it prevails among a people will prevent, the cruel practice of privately slandering the reputation of elevated characters. To wound in the dark is an easy thing, and a small capacity influenced by a bad heart can do it effectually. Unfounded jealousies, are as dangerous to the public as to those who suffer them, and by being often repeated, shake the foundation of government, and place the worthy and unworthy, on the same level of confidence in the minds of the people.

Religion is the best friend of men’s liberties and properties. Under his influence, government will be just to all its engagements, and the interest of every citizen stand secure, on the basis of equity and justice. Where the spirit and practice of religion reigns, the sigh of oppression will cease, and men no longer groan under the power of their brethren. A great part of the happiness of the world, must be attributed to the humane influence of the religion of Jesus, and the remainder of oppression is a witness how imperfectly his doctrines are understood, and how little there is of his spirit, even in the countries which are called Christian. On the ground of prophetic assurance we expect a day, in which this religion shall fill the earth, and when it happens, there will be no traffick in the bodies and souls of men; oppression and slavery will cease and the image of the Creator in reason and understanding, will be allowed as evidence of a right to the privileges of his family.

Our subject recommends to the rulers of the state, an encouragement of all those institutions, by which religion and science are diffused among the people. It is the manner of divine wisdom, to work by means regularly established. When the institutions of religion fall into disrepute, we have no right to expect, that the spirit of piety will prevail among the people. The visible orders of religion are an enclosure, which holds its friends together; and under an idea of tolerancy many have run into an opposite extreme of opinion, that in all cases where men pretend conscience, they ought to be exempted from the direction of law. To argue much on these matters may not be salutary, but I think a little attention will determine the point; for when we look on those districts within the United States, in which all legal protection hath been denied to the institutions of religion, we can easily trace the political evils, jealousies and confusion which have ensued.

Science is friendly to religion and good order, and on this ground claims protection from government. The expences of education are the most economical deposit which can be made for the liberties of our offspring. Men of information will neither forfeit, nor quietly submit to the loss of their civil rights; but the ignorant are ensnared by their brethren. Much therefore is due to the minds of our youth, who will fill the first offices in the state and in the church and be the only pillars of order, when a few years have laid this honorable and pious Assembly in the dust.

If religion and science are the strength of the state, and the preservation of public liberty, we ought to reflect with gratitude on the goodness of God, in furnishing so many characters eminent in both. When we look on this collection, it calls to our remembrance many of our fathers, who, by their piety and wisdom, were pillars in our Israel; and who now receive a more permanent reward than men can give. It is but a small return, which even a grateful people can make to the fidelity of their rulers; but tho we cannot reward, an acknowledgement of the obligation is beautiful, and must encourage their hearts in doing us good. The chief officers of the state, who are gathered before the Lord on this occasion, to bless his name and ask his presence, have a right to our dutiful address.

The God of our fathers who hath all power and dominion, hath been pleased to put an important trust into your hands, and select you as the instrument of exercising his government, and dispensing his favor to this people. Tho an elevated station among men, cannot divest you of the weaknesses of humanity; tho we make no doubt, but in the presence of a higher ruler you feel in yourself all the imperfections of a creature; yet you will indulge us in returning our thanks, for many benefits you have rendered to the state, and especially for the undeviating testimony you have borne in favor of religion, both by your precept and example. Much is in the power of your excellency; tho the Gods of the people must die like men, and be soon reduced to a level with their brethren, yet they have a weighty influence on public opinion and practice, and the happiness of many, perhaps even for another world, stands or falls with them. Impressed with this truth, we look to our first Magistrate to do more than any other man can do. You stand in the place of the Lord to this people—they consider you cloathed with an authority from Heaven—they have confidence in your singular art of presiding with united firmness and moderation—well as an inclination men have to imitate the great, they will be strongly impelled by your example. While subordinate orders of men in the state have their sphere of duty and influence, we look to you, Sir, to be the most decided and powerful friend of that religion and righteousness, which is the true wisdom of government, and will establish our prosperity on a permanent basis. To our rulers, and chiefly to your care, we have committed everything that is dear to us on earth; our lives, properties, liberties and happiness, hoping that by a mild administration, you may be able to preserve the betrustment; but if severity be at any time necessary, to restrain the invasions of vice, we shall pray without ceasing, that the God of Heaven will give you wisdom to use the sword he hath put into your hand. The honor of being first among many is great; but much greater is the honor of being faithful to God who hath given this appointment, and of exercising it like a good man; and while we gratefully acknowledge the dignity of your station, we beseech the most high to make you a Christian indeed, and fill your heart with the comforts of undefiled religion. The reward which we cannot give, your Excellency will find in living near to God, in feeling your dependence on his grace thro the Redeemer, and in adoring his holiness. When wearied with the cares of State, in the retirement of devotion you will feel and say, it is good to be here. And when Almighty God takes you from this people and the honorable trusts he hath given you on earth, may you dwell forever in his love.

May I likewise be permitted to express the public regard and expectations, to the Honorable Lieutenant-Governor, the Council, and House of Assembly.

This annual presentment before God, of the Rulers and chief Estates of the land, is an event which must interest the feelings of a pious mind. It cannot fail to enkindle in us a reverent devotion, when we behold the princes, the heads of families and representatives of the people, addressing our heavenly King for his blessing and direction. This anniversary of worship is a solemn engagement before God, that the government shall be according to his will; that a respect for his institutions shall be maintained, and religion encouraged. If you, who are the honorable of the land, countenance virtue and justice; if piety is conspicuous in your lives; if industry, temperance, justice and a fear of God, are patronized by the laws you enact; if you appoint persons of wisdom and discreet goodness to execute the laws of the State; good order will prevail and vice be ashamed: But without this aid from you, Honorable Gentlemen, there is reason to expect that licentiousness will break over every barrier, dishonor God who hath so often protected this people and their fathers, and induce a general wretchedness. The experience of all people witnesses the sacred truth, that righteousness exalteth a nation; and it is also a truth as certainly known, that the manners of a people, do in a great measure take their complexion from public measures. When we consider how much your respectable body can do for God, and the eternal interest of men, we must earnestly solicit your care, to preserve the purity of the people, to encourage good living, and reward by your confidence in them, such men as fear the Lord and obey his law.

The local situation of your honorable body, in every part of the State; your opportunity for personal observation of the manners in every district;–the force of your example, united with legislative authority, will essentially aid you in doing what is requested. The harmony of the people and peace of the land follows the harmony and union of their Rulers; and when the citizens see that every kind of vice is discountenanced by those in dignified stations, it will be a powerful guard of their principles and manners. To stand the guardians of public happiness is a solemn situation, and one in which every man needs to be divinely assisted.—Honorable Gentlemen, may the God of wisdom make you skillful to govern and wise unto eternal peace.

The sons of Aaron are also before the Lord. The sanctity of their profession, and its near connection with my subject, naturally calls my address to them:

The duty incumbent on all Christian citizens, piety towards God, and righteousness and love to men, is doubly incumbent on us. We are consecrated to the service of religion, and under the most solemn vows. There is every reason, that we use a greater diligence than other men, in promoting a divine knowledge of God and his Son, love, faith, vital piety, experimental religion and a good practice. If those who act in the civil department, are judged guilty for spiritual negligence; how much greater is the criminality of a gospel minister, who is expressly set apart as a watchman for the souls of men. From the advantage to be derived in this life, we have the same inducement as other men, to urge the power and practice of godliness; national prosperity is a motive which will animate the heart of every good man. Tho not cloathed with civil power, we are connected with the state. Wise men of every profession, know the salutary influence of an enlightened and pious clergy, on the civil system, and therefore much is expected from us; and much may be done to advance justice and peace, encourage obedience to the laws, and strengthen the hand of government. But more weighty considerations are drawn from another world. The souls of this people are to be happy or wretched forever, and of this happiness or misery we are the messengers. To describe the perfections and will of God; to assert his government, and declare his wrath against sin; to publish the Gospel of Jesus Christ, and explain its peculiar doctrines, which are full of holiness and love; to urge a Christian faith and practice; to encourage men by the glory promised to godliness, and awaken them by the terrors of the Lord prepared to avenge iniquity; to be an example to the church in humility, sobriety and every grace, are our peculiar duties; and we cannot excel in them without much labour and prayer. For the right performance of these duties, there is a peculiar necessity that we take much care of our own hearts, and be personally warmed with love to God and men. Whatever assists us to love religion, will furnish us with ministerial accomplishments, especially to abound in prayer, will comfort, enlighten and assist us in every duty, and give us a happy preparation, thro divine mercy, for that immortality which we preach to others. Let us be united in a fervent charity, and in supplication for an out-powering of the spirit, on us and on our churches, and when our Lord cometh he will make us perfect unto eternal peace.

My Brethren of every character, let us resolve here before the Lord that we will serve him. Blessed are the righteous; but one sinner destroyeth much good, and disturbeth his land. This honorable legislature are the anointed ones of the Lord; it is our duty to pray that they may be endowed with wisdom, to give them reverence, and to honor all the Judges and ministers of justice in the land. Our political happiness in a great degree depends on our own conduct, for a vicious people cannot be a happy one.

Especially let us endeavour by faith and patience, by charity and good works, to obtain the promises, and secure to ourselves a habitation not made with hands, eternal in the heavens. How precious are these moments of time, and who can describe how much depends on a right improvement of them? The soul which remains in sin shall die; but for the pure in heart, there is reserved an inheritance, incorruptible, undefiled, and that fadeth not away. Amen.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!