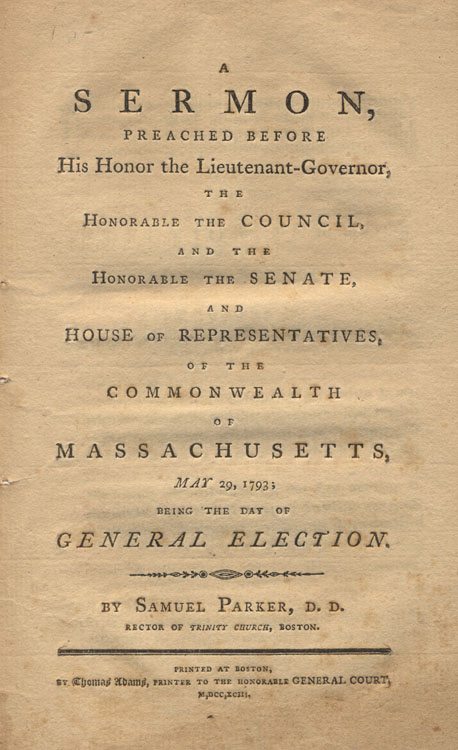

Samuel Parker (1744-1804) graduated from Harvard in 1764. He was assistant rector (1774-1779) and later rector of Trinity Church in Boston (1779-1804). During the Revolutionary War, Parker sided with the Americans over the British. The following election sermon was preached in Massachusetts on May 29, 1793.

SERMON,

PREACHED BEFORE

His Honor the Lieutenant-Governor,

THE

Honorable the SENATE,

AND

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES,

OF THE

COMMONWEALTH

OF

MASSACHUSETTS,

May 29, 1793;

BEING THE DAY OF

GENERAL ELECTION.

By Samuel Parker, D. D.

RECTOR OF TRINITY CHURCH, BOSTON.

Commonwealth of MASSACHUSETTS.

In SENATE, May 29, 1793.

ORDERED, That Thomas Dawes, and Benjamin Austin, jun. Esquires, be a Committee to wait on the Rev. Doctor Samuel Parker, and thank him in the name of the SENATE, for the SERMON delivered by him this day, before his Honor the Lieutenant-Governor, the Honorable Council, and the two Branches of the Legislature; and to request of him a Copy thereof for the Press.

Attest.

SAMUEL COOPER, Clerk.

ELECTION SERMON.

PROVERBS xiv. 34.

RIGHTEOUSNESS EXALTETH A NATION: BUT SIN IS A REPROACH TO ANY PEOPLE.

The great source of all human knowledge is experience; and that experience which teaches us practical wisdom, and informs us of the many evils that constantly wait on life, is acquired chiefly by observation and reflection. Time, indeed, is continually forcing the instructions of this sage monitor on our notice, and when “length of days” has not made us sufficiently acquainted with her, we fly to the aged that we may learn her counsels; or read them with sufficient certainty, in the misconduct, disappointment, and miseries of others.

The Historian makes it his particular glory, that by faithfully recording the fates of kingdoms, by delineating the virtues which raised some to magnificence, and the vices which brought others gradually to destruction, he anticipates the future by a true representation of the past, and teaches men wisdom by the example of others. But though, from the short period of human life, the narrowness of our views, and the necessary calls of duty, we are obliged to recur to the experience of those who have gone before us, for almost all our knowledge; yet the few events that happen to ourselves, or that fall within the circle of our own observation, make a far more lasting impression on us, and have a much greater influence over the heart.

The strange vicissitudes of fortune, that happen either to nations or individuals, we hear with faint emotion, and often regard them only as they serve to gratify curiosity, and increase our store of knowledge. The Historian’s eloquence, and the Poet’s fancy can scarcely raise the tear of sympathy, while they relate, with all the decoration of language, the miseries of life; and those sorrows which only the best and softest bosoms feel occasionally for the calamities of others, are but of short duration. They vanish quick as the morning dews dissolve before the rising sun, and oft, like them, “leave not a trace behind.” But such calamities and disappointments as befall ourselves, are considered as dear bought experience, and treasured up in the heart. These are the counselors that will make us wise and good; unless in despite of reason and of nature, we suffer life to glide away unnoticed, without improvement in knowledge or in virtue.

Serious reflection on what has passed, with a constant habit of comparing it to the future, seems, indeed, to be a rule of moral discipline, natural to the mind of man, and is one of the greatest safeguards of virtue, as well as the best means of acquiring useful knowledge. The fluctuating state of our minds makes it necessary to take these retrospective views of life, that we may increase in prudence, and establish ourselves in virtue.

Under the full persuasion of the efficacy of this principle, as well as the influence of the Divine Spirit, the Proverbs of Solomon, which have always been esteemed a most valuable part of the holy Scriptures, were written. He says himself, that they were the fruits of his most profound meditations, and of his most excellent wisdom. Because the Preacher was wise, he still taught the people knowledge; yea he gave good heed, and fought out, and set in order many Proverbs. 1 To give the more weight and dignity to his precepts, he delivers them not as his own, but as those of Wisdom herself; and in the poetic and dramatic way, introduces her as a divine person, the favourite offspring and first born of God, who dwelt with him before the foundations of the earth were laid, before time and the world was, and who is sent forth from him to guide, and instruct the children of men.

Among these Proverbs or wise sayings, we find many excellent rules for the conduct of human life, and for leading men to happiness. But perhaps there is not anything in the whole book, of greater importance to us, as members of civil society, than the aphorism contained in our text. Righteousness exalteth a nation, but sin is a reproach to any people.

It is well known, that the word righteousness is used, in the sacred writings, with different degrees of latitude. Sometimes, it is applied in a confined sense, as signifying that uprightness, equity and justice, which we should maintain in our treatment of our fellow creatures, by rendering to all their proper dues; and is synonymous with justice. But the word is usually taken in a more extensive signification, as descriptive of goodness in general. IN this sense the righteous man is one, who acts well in all the relations and characters in which he is placed; who lives in the practice of piety, benevolence, self government and universal goodness. In this larger meaning, the term is most commonly used throughout the Psalms, the Proverbs and the New Testament. Thus, To him that soweth righteousness shall be a sure reward. As righteousness tendeth to life, so he that pursueth evil, pursueth it to his own death. It is in this extensive sense, that the word is undoubtedly used in our text. A righteous person is one who maintains an upright, holy and virtuous part through the whole course and tenor of his life. He is one, who seriously considers, and steadily discharges the general obligations of piety and goodness. This, no doubt, will necessarily include in it, his being righteous in the strict and limited signification of the term. He makes a point of preserving an exact fidelity and equity in his intercourse with mankind. According to the best of his abilities he renders to his fellow creatures their dues, and treats them in a manner agreeable to the various claims, of one kind and another, which they have upon him. He is true to his engagements, and faithful to his promises.

Besides this, he performs the other offices and duties of the virtuous character. He is not only honest and equitable, but kind and benevolent. He endeavours to promote the welfare of those around him, and to behave, in every respect, as one who is animated with the principles of affection to his brethren of the human nature. He makes it his labour, his delight, to render them happy, so far as the capacity of doing it, which Providence hath put in his power, extends.

Nor, while he is just and generous towards men, is he unjust to, or forgetful of, the ever blessed God. He seriously considers his obligations to the greatest and best of beings, and is solicitous to testify his sense of them, by all the returns which he is capable of making. Hence he cultivates the deepest reverence for the sacred name of his Marker, and the warmest sentiments of devotion towards him. Hence he loves his high Creator and Benefactor, above every object beside, is truly thankful for the mercies he receives from him, trusts in his protection and support, submits to his will, and is obedient to his commands.

Equally intent is the righteous man upon maintaining and cherishing the personal virtues. He keeps himself in the exercise of self government, temperance, moderation, meekness, humility and contentment. In short, he endeavours to be found in all the commandments and ordinances of the Lord blameless, and to preserve all the graces of the spiritual life.

Such is the righteousness the wise man speaks of as exhibited in practice; and a righteous nation consists of a number of individuals whose character and conduct are such as we have now briefly delineated.

The sin mentioned in our text, as the reproach of a people, must be considered as the opposite to this great and good character. When the people composing a nation shew no regard to the eternal rules of equity and justice; when true religion decays, and they lose their reverence for the Divine Being; when they despise his institutions, and profane his Sabbaths, when they ridicule his word, and indulge themselves in the breach of his commands; when infidelity and vice prevail; when impiety and irreligion mark the character of a people—then iniquity abounds, and they are under the influence of that sin, which is their greatest reproach.

Taking then the word righteousness in the sense we have explained it, to signify religion and virtue in general, our text naturally presents us with a subject, which, I flatter myself, will not be considered as altogether foreign from the design of our present assembling, viz. THE HARMONY OF RELIGION AND CIVIL POLITY; or, that religion and virtue are the surest means of promoting national happiness and prosperity.

When Solomon asserts that religion or righteousness exalteth a nation, we are not to understand the proposition in so strict and absolute a sense, as that true religion is so necessary, in all its doctrines, and in all the extent of its precepts, that there have been no instances of the prosperity of societies, which have not been wholly regulated by it. Some States, it must be acknowledged, which have been only partially governed by its maxims, have enjoyed long and glorious advantages upon the theatre of the world; either because their false religions contained some principles of rectitude, in common with the true religion; or, because God, in order to animate and encourage such people to the practice of some virtues, necessary to the very being of society, annexed success to the exercise of them; or, because rectitude was never so fully established upon earth, as to preclude injustice from enjoying the advantages of virtue, or virtue from suffering the penalties of vice. However this may be, we affirm, that the most sure method that a nation can take to support and exalt itself, is to follow the laws of righteousness, and the spirit of religion.

Nor is it asserted in our text, that, in every particular case, religion is more successful in procuring some temporary advantage than the violation of it; so that to consider society only in this point of light, and to confine it to this particular case, independently of all other circumstances, religion yields the honour of temporary prosperity to injustice. Some State crimes may have been successful, and have been the steps by which certain nations have acquired worldly glory. And should we acknowledge that virtue has sometimes been an obstacle to grandeur, still the truth of the proposition in our text stands unimpeached—that if we consider a nation in every point of light, and in all circumstances, it will be found that the more a society practices virtue, the more prosperity it will enjoy; the more it abandons itself to vice, the more misery it will sooner or later suffer; so that the very vice which contributed to its exaltation, will produce its destruction, and the virtue which seemed at first to abase it, will in the end exalt its glory.

We observe further here, that by a nation’s being exalted, the inspired author of our text does not intend such an elevation as worldly heroes, or rather tyrants, aim at. If, by exalting a nation, is understood an elevation extending itself beyond the limits of rectitude; an elevation not directed by justice and good faith, consisting in the acquisitions of wanton and arbitrary power, obliging other nations to submit to a yoke of slavery, and thus becoming an executioner of divine vengeance on all mankind—we allow, that in this sense, exaltation is not an effect of righteousness. But, by exalting a nation, the wise man intends, whatever promotes the greatest happiness and prosperity of its citizens; its being governed by wise and wholesome laws, enjoying liberty and equal government, negotiating itself with resolution enjoying every blessing conducive to the prosperity and happiness of a people; and at the same time blessed with the favourable notice and regard of the Divine Being. Such an exaltation is obtained only by righteousness.

In a word, it is not the lot of humanity, that the prosperity of any nation should be so perfect, as to exclude all untoward circumstances. The meaning of our text must be, that the highest glory, and the most perfect happiness, which can be enjoyed by a nation, in a world, where, after all, there must be a mixture of adversity with prosperity, are the fruits of righteousness. No nation was ever yet free from evils and inconveniences of many kinds; and even the most virtuous societies have been suffered to labour under many straits and difficulties; and it must be allowed, that this world will always be to public bodies what it is to individuals, a place of misery and unhappiness; and therefore we must understand our text as asserting only, that the most solid happiness, which can be enjoyed here below, has righteousness for its cause. It is the more necessary to restrain it within these limitations, not only because they explain the sense of the inspired author, but because they serve to preclude such objections, to unravel such sophisms, and to solve such difficulties, as infidels and libertines have urged against its truth.

To prove, then, that religion and virtue are the surest means of promoting national happiness and prosperity, let us consider the origin of civil government, and the motives which induced mankind to unite themselves in society. By doing this, we shall perceive that righteousness is the only thing that can render nations happy.

Every individual has a great variety of wants, and but few, and those very limited, faculties to supply them. Every individual of mankind has need of knowledge to inform him, of laws to direct him, of property to support him, of food to nourish him, of clothing and covering to defend him against the inclemencies of the seasons. This catalogue of our various and respective wants might easily be enlarged. Similar interests form a similar design. Divers men unite themselves together, in order that the industry of all may supply the wants of each. Hence the origin of societies and public bodies of men.

The author of our being has also given to man a nature fitted for, and disposed to, society. It was not good for man at first to be alone; his nature is social, having various affections, propensities and passions, which respect society, and cannot be indulged without a social intercourse. The natural principles of benevolence, compassion, justice, and indeed most of our natural affections, powerfully incite to, and plainly indicate that man was formed for, society.

The social affections of our nature, and the desire of the many conveniences, not to be obtained or enjoyed, without the concurrence of others, probably first induced men to associate together. But the depravity of our nature since the apostacy, and the great prevalency of lusts and corruptions, have obliged mankind to enter into closer connections and combinations, for mutual protection and assistance. Thus civil societies and governments were formed, and in this way government comes from God, and is his ordinance. The kingdom is the Lord’s, and he is the Governor among the nations. By him kings reign, and princes decree justice, even all the judges of the earth.

The end and design of civil society and government, from this view of its origin, must be to secure the rights and properties of its members, and to promote their welfare and happiness; or, in the words of inspiration, that men may live quiet and peaceable lives, in all godliness and honesty.

It is easy to perceive then, that in order to enjoy the blessings proposed by this assemblage, some fixed maxims must be laid down, and inviolably obeyed. It is necessary that all the members of this body should consider themselves as naturally equal; that by this idea they may be inclined to afford each other mutual succor. It is requisite that they should be sincere to each other, lest deceit should serve for a veil to conceal the sinister designs of some from the eyes of the rest. The rigid rules of equity should be inviolably observed, that so they may fulfill the contracts, which they bound themselves to perform, when they were admitted into this society. Esteem and benevolence ought to give life and action to righteousness. It is of the utmost consequence, that the happiness of all should be preferred before the interest of an individual; and that in cases where public and private interests clash, the public good should always prevail. Every citizen ought to cultivate his own talents, that he may contribute to the happiness of that society, to which he ought to devote himself with the utmost sincerity and zeal. These duties are absolutely necessary for the welfare and prosperity of societies. And what can be more proper to make us observe these rules than religion,–than righteousness? Religion brings us to feel our natural equality; it teaches us that we originate in the same dust; have the same God for our Creator; are all descended from the same first Parent; all partake of the same miseries, and are all doomed to the same last end. Religion teaches us sincerity to each other; that the tongue should be a faithful interpreter of the mind; that we should speak every man truth with his neighbour; and, that being always in the sight of the God of truth, we should never deviate from the laws of truth. Religion teaches us that we should be just; that we should render to all their dues; tribute to whom tribute is due; custom to whom custom; fear to whom fear; honour to whom honour; that whatsoever we would men should do unto us, we should do even so unto them. Religion requires us to be animated with charity,–to consider each other as creatures of one God, subjects of the same heavenly King, members of one body, and heirs of the same glory. It requires us to give up our private interest to the public good, not to seek our own, but everyone another’s wealth; it even requires us to lay down our lives for the brethren. Thus if we consider nations in these primitive views, it is righteousness alone that exalts them.

Were we to defend from these general principles, and take into view the particular forms of government, which have been adopted by the various nations upon earth; or rather, which have grown out of particular occasions and emergencies; from the fluctuating policy of different ages; from the contentions, successes, interests and opportunities of different orders and parties of men among them (for such we shall find was the origin of most of the particular forms of government in the world,) we shall be convinced that each nation has been, more or less happy, in its own mode of governing, has more or less prevented the inconveniences, to which its form of government is subject, according as it has been more or less attached to religion or righteousness. The precepts and the maxims of religion, applied to these imperfections, would effectually restrain all those excesses, and preclude those evils, from which the most perfect forms of government are not entirely free. But the time will not permit us to enter into so particular an inquiry, or to multiply quotations to prove this point.

I proceed to observe, secondly, that the doctrine of Providence will furnish us with another argument, to prove the truth of our text.

The conduct of Providence, with regard to public bodies is very different from that, which prevails in the case of individuals. It is a rule in the divine government, to deal with nations according to their moral character. Perfect justice is the invariable rule of his dominion over public bodies. In regard to individuals, Providence is involved in darkness. Many times it seems to condemn virtue, and crown injustice; to leave innocence to groan in silence, and to empower guilt to riot, and triumph in public. The wicked rich man fared sumptuously every day, while Lazarus desired, in vain, to be fed with the crumbs that fell from his table. St. Paul was executed on a scaffold, while Nero reigned on Caesar’s throne.

But Providence is directed in a different method, in regard to public bodies. Prosperity in them is the effect of righteousness; public happiness is the reward of public virtue; the wisest nation is usually the most successful, and “virtue walks with glory by her side.” The work of righteousness shall be peace, and the effects of righteousness, quietness and assurance forever. On the other hand, the judgments of Heaven are commonly showered down upon a wicked people; he turneth a fruitful land into barrenness, for the wickedness of them that dwell therein.

God sometimes, indeed, afflicts the most virtuous nations; but he does so with the design of purifying them, and of opening new occasions to bestow larger benefits upon them. He sometimes, indeed, prospers wicked nations; but their prosperity is an effort of his patience and long suffering; it is to give them time to prevent their destruction, and by his goodness, to lead them to repentance. But, as before observed, prosperity usually follows righteousness in public bodies; public happiness is the reward of public virtue; the wisest nation is the most successful, and glory is generally connected with virtue. And this conduct of Providence is grounded on this reason. A day will come when Lazarus will be indemnified, and the rich man punished; when St. Paul will be rewarded, and Nero will be confounded. Innocence will be avenged, justice satisfied, the majesty of the laws repaired, and the rights of God maintained.

But such a retribution is impracticable in regard to public bodies. A nation cannot then be punished as a nation, nor a kingdom as a kingdom. All the different forms of government will then be abolished. While some of the human race are put into possession of glory, others will be covered with shame and confusion of face. It seems then, that Providence owes to its own rectitude, those times of vengeance, in which it pours all its wrath on wicked nations; sends them wars, famines, plagues and other catastrophes, of which history gives us so many memorable examples. To place hopes altogether on worldly policy; to pretend to derive advantages from vice, and so to found the happiness of society, on the ruins of religion and virtue, is little short of insulting Providence. It is to arouse that power against us, which, sooner or later, overwhelms and confounds vicious societies.

But if the obscurity of the ways of Providence, which usually renders doubtful, our reasonings upon the divine conduct, weaken this argument, let us consider the declarations of God himself upon this point.

The whole 28th chapter of Deuteronomy, all the blessings and curses pronounced there, fully prove our doctrine. Read the tender complaint, which God formerly made concerning the irregularities of his people. O that they were wise, that they understood this, that they would consider their latter end! How should one chase a thousand, and two put ten thousand to flight. Agreeably to this, are the affecting words uttered by the mouth of the Psalmist—O that my people had hearkened unto me, and Israel had walked in my ways. I should soon have subdued their enemies, and turned mine hand against their adversaries. Their time should have endured forever. I should have fed them also, with the finest of the wheat, and with honey out of the rock should I have satisfied them. What noble promises are made also by the ministry of Isaiah? Thus saith the Lord thy Redeemer, the Holy One of Israel, I am the Lord thy God which teacheth thee to profit; which leadeth thee by the way thou shouldst go. O that thou hadst hearkened to my commandments! Then had thy peace been as a river, and thy righteousness as the waves of the sea; thy seed also had been as the sand, and thy name should not have been cut off, nor destroyed before me. Observe also the terrible threatnings, denounced against backsliding Israel, by the prophet Jeremiah. Though Moses and Samuel stood before me, yet my mind could not be toward this people; cast them out of my sight, and let them go forth. And it shall come to pass, if they say unto thee, Whither shall we go forth? Then thou shalt tell them; Thus saith the Lord, Such as are for death to death, and such as are for the sword to the sword, and such as are for the famine to the famine, and such as re for captivity to captivity. Thou hast forsaken me, saith the Lord, thou art gone backward; therefore will I stretch out my hand against thee, and destroy thee: I am weary of repenting.

Not to multiply quotations; we find that through the whole history of the Old Testament, the interchangeable providences of God, towards the Jewish nation, were always suited to their manners. They were constantly prosperous or afflicted, according as religion and righteousness flourished, or declined among them.

Nor was this Providence exercised only towards his own people but he dealt thus with other nations as their history evinces; and thus the truth of our text is proved by experience. Were we to consult the ancient history of the Egyptians the Persians, or the Romans, who surpassed them all, we shall find they were by turns exalted as they respected righteousness or abased, as they neglected it.

By what mysterious art did ancient Egypt subsist, with so much glory, during the period of fifteen or sixteen ages.2 By a benevolence so extensive, that he, who refused to relieve the wretched, when he had it in his power to assist him, was himself punished with death: by a justice so impartial, that their kings obliged the judges to take an oath, that they would administer impartial justice to all, though they, the kings themselves, should command the contrary: by an aversion to bad princes so fixed, as to deny them the honours of a funeral: by entertaining such just ideas of the vanity of life, as to consider their houses as inns, in which they were to lodge, as it were, only for a night; and their sepulchers as habitations in which they were to abide for many ages; for which reason, they united, in their famous pyramids, all the solidity and pomp of architecture: by a life so laborious, that even their amusements were adapted to strengthen the body, and improve the mind: by such a remarkable readiness to discharge their debts, that they had a law, which prohibited the borrowing of money, except on condition of pledging the body of a parent for payment; a deposit so venerable, that a man who deferred the redemption of it, was looked upon with horror: in a word, by a wisdom so profound, that Moses himself is renowned in Scripture for being learned in it.

The Persians, also, obtained a distinguished place of honour, in ancient history, by considering falsehood in the most odious light, as a vice the meanest and most disgraceful; by a noble generosity, conferring favours on the nations they had conquered, and leaving them to enjoy all the ensigns of their former grandeur; by an universal equity, obliging themselves to publish the virtues of their greatest enemies; by educating their children so wisely, that they were taught virtue, as other nations were taught letters. The children of the royal family, and of the nobles, were, at an early period of life, put under the tuition of four of the wisest and most virtuous statesmen. The first taught them the worship of the gods; the second trained them up to speak truth, and practice equity; the third habituated them to subdue voluptuousness, and to enjoy real liberty; to be always masters of themselves and of their own passions; and the fourth inspired them with courage; and by teaching them how to command themselves, taught them how to rule over others.

3 The Romans founded their system of policy upon that best and wisest principle, the fear of the gods; a firm belief of a divine superintending Providence, and a future state of rewards and punishments. Their children were trained up in this belief from tender infancy, which took root and grew up with them, by the influence of an excellent education, where they had the benefit of example, as well as precept. Hence we read of no heathen nation in the world, where, both the public and private duties of religion, were so strictly adhered to, and so scrupulously observed, as among the Romans. They imputed their good or bad success to the observance of these duties, and they received public prosperity, or public calamities, as blessings conferred, or punishments inflicted, by their gods. Though the ceremonies of their religion justly appear to us, instances of the most absurd and most extravagant superstition, yet, as they were esteemed the most essential acts of religion, by the Romans, they must consequently carry all the force of a religious principle.4 Cicero, the great Roman orator and philosopher, speaking of his countrymen, says, We neither exceeded the Spaniards in number nor did we excel the Gauls in strength of body, nor the Carthagenians in craft, nor the Greeks in arts and sciences: But we have indisputably surpassed all the nations in the universe, in piety and attachment to religion, and in the only point that can be called true wisdom, a thorough conviction, that all things here below, are directed and governed by Divine Providence. To this principle alone, he wisely attributes the grandeur and good fortune of his country. From this principle proceeded that respect for, and submission to, their laws; and that temperance, moderation, and contempt for wealth, which are the best defense against the encroachments of injustice and oppression. Hence too arose that inextinguishable love for their country, which, next to the gods, they looked upon as the chief object of veneration. 5 This they carried to such an height of enthusiasm, as to make every tie of social love, natural affection, and self preservation, give way to this duty to their dearer country. Hence proceeded that obstinate and undaunted courage, that insuperable contempt of danger, and death itself, in defense of their country, which complete the idea of the Roman character, as it is drawn by the historians, in the virtuous ages of the republic. As long as the manners of the Romans were regulated by this first great principle of religion, they were free and invincible. But the atheistical doctrine of Epicurus, which insinuated itself at Rome, under the respectable name of Philosophy, undermined and destroyed this ruling principle. The luxuries of the East, after the conquest of Asia, corrupted the manners of the Romans, weakened this principle of religion, and prepared them for the reception of atheism, which is the never failing attendant on luxury. And thus, by their rapid and unexampled degeneracy, was brought on the total subversion of that mighty republic.

Were we to inquire into the reasons of their decline; were we to compare the Egyptians under their wise kings, with the Egyptians in a time of anarchy; the Persians victorious under Cyrus, with the Persians enervated by the luxuries of Asia; the Romans at liberty under their consuls, with the Romans enslaved by their emperors, we should find, that the decline of each was owing to sin, which is a reproach to a people; to the practice of vices, opposite to the virtues which had caused their elevation; we should be obliged to acknowledge, that a total disregard to religion and righteousness; luxury, voluptuousness, disunion, corruption, and boundless ambition, were the odious means of subverting states, which, in the heighth of their prosperity, expected to endure to the end of time.

Having thus established the truth contained in our text, let us employ a few moments in reflecting on what has been said.

In the first place. What gratitude is due from us to the King of kings, for affording us better means of knowing the righteousness, that exalts a people, and more motives to practice it, than all the nations of antiquity. They had only a superficial, debased, confused knowledge of the virtues, which constitute substantial grandeur; and as they held errors in religion, they must necessarily have erred in civil polity. Our heavenly Father, glory be to his name, has placed at the head of our councils, the most perfect Legislator, that ever held the reins of government in the world. This Legislator is Jesus Christ. His kingdom, indeed, is not of this world, but the rules, he has given us to arrive at his heavenly kingdom, are the most proper to render us happy in the present state. When he says, Seek ye first the kingdom of God, and his righteousness, and all other things shall be added to you; he gives the command, and makes the promise, to whole nations, as well as individuals.

Who ever carried, so far as this divine Legislator, ideas of the virtues we have mentioned, and by practicing which, nations are exalted? Whoever formed such just notions of that benevolence, that love of social good, that magnanimity, that generosity to enemies, that wisdom, justice, and equity, that frugality, and devotedness to the public good, and all the other virtues, which render antiquity venerable to us? Who ever gave such wise instructions to kings, and subjects; to magistrates and people; to citizens and soldiers; to the world and the church? We are better acquainted with these virtues, than most of the nations of the world. We are able to carry our glory, far beyond the nations of antiquity; if not that glory, which glares and dazzles, at least that which makes tranquil and happy, and procures a felicity far preferable to all the pageantry of heroism, and worldly splendor.

Let not these things, my friends, be matters of mere speculation to us. Let us endevour to reduce them to practice. Never let us suffer our political principles to clash, with the principles of our religion. Far, far be from us, and from our rulers, that deceit and hypocrisy, that falsehood and insincerity, that dissimulation and craftiness, those abominable maxims, which a depraved Florentine 6 recommended to statesmen. Let us obey the precepts of Jesus Christ, and practice that righteousness which exalteth a nation, and by so doing, we shall draw down blessings on our nation, more pure and perfect than those, we now enjoy. The blessings we now enjoy, are such as ought, on this auspicious anniversary, to inspire us with lasting gratitude to the great Arbiter of nations,–to him who setteth up one, and putteth down another.

It was a favourite method of instruction with the Jewish Legislators and Prophets, to recur to the history of their nation; to ancient events, and also to such as took place, in a period coeval with themselves, in order to excite a correspondent gratitude, and a spirit of religious obedience, in the breasts of the people. The time will not admit us to adopt the same plan, and enter into such an extensive discussion: A few, however, of the more general, and more conspicuous, you will permit me to glance at.

The first is the blessing of public peace. When we look back on the difficulties and dangers, in which the United States were involved, in the late contest with Great Britain; when we reflect on the perils and disasters we experienced, when surrounded with scenes of horror and devastation—with the depredations and shocking ravages of war—when our liberties, our country, and even life itself might be said to “hang in doubt,” and contrast it with the present peaceable state of our nation, we must acknowledge the gracious interference of almighty God, in our favour.

While wars and rumours of wars are now spreading, and prevailing through all Europe—while nation is rising against nation, and kingdom against kingdom—while the old world is generally convulsed, and tottering under those signs and symptoms, which denote approaching dissolution,–to us is given, and as yet continued, the blessing of peace.

How long we shall enjoy this greatest of the divine favours, the commotions, which have overspread the European nations, have rendered very uncertain. No one can doubt, that our interest, our safety, and our happiness, as a nation, forbid us to interfere in their quarrels. Whether the faith of treaties, or principles of gratitude, for services performed in our distress, call upon us to hazard our own peace and prosperity, it is neither prudent, nor proper to discuss, in this place. This is a subject that rests in the Supreme Executive of the United States; in the wisdom, firmness, and prudence of which, we are happy that we can place entire confidence.

The present appears to be as eventful an era, as any the annals of mankind can furnish. A combination of events seems to be manifestly tending to bring about some mighty revolution, among the nations of the earth. History has scarcely ever before furnished us, with an instance of a populous, and powerful nation, throwing off the yoke of despotism, and acquiring sentiments and habits, congenial to a great and free republic. We have seen the mists of ignorance and error fast rolling away, and the benign beams of liberty, freedom and science, spreading their lustre over the mighty kingdom of France. The flame caught from America, and the spirit of patriotism illumined that whole nation. What generous mind did not espouse its cause? What friend to liberty, and equal rights did not wish them success?

But alas! the fair countenance of freedom has been overspread with a dark veil; and the victims, which popular anarchy and ferocity have sacrificed, must be allowed to have sullied the glories of a revolution, which bid fair to astonish the world. It is forever to be regretted, that any dark shade of ferocious revenge should eclipse the glory of establishing liberty, and freedom, in that nation. But where do the records of history point out a revolution, unstained by some actions of barbarity? When do the passions of human nature rise to that pitch, which produces great events, without wandering into some irregularities? Perhaps, at so great a distance as we are placed, and with so small means of authentic information, we are not capable of forming a proper judgment of their conduct, and the reasons of all their actions; but must patiently wait for the pen of the impartial historian, to enable us to decide, how far to justify or condemn. Should an apology, for that mental intoxication that seems to have influenced them, be necessary, or proper to be here inserted, permit me to give it, in the words of a very sprightly female writer. 7 “Let us remember,” says she, “that the great cause of liberty remains uncontaminated, by the assassinations at Lisle. Though fanatical bigots, in the rage of superstitious cruelty, have dragged their victims to the stake, would it be rational to extend our abhorrence of such actions to Christianity itself?—to that benevolent religion, which inculcates universal charity, love and good will towards men; and choose the comfortless, the sullen indifference of atheism? And shall we, because the fanatics of liberty have committed some detestable crimes, conclude that liberty is an evil, and prefer the gloomy tranquility of despotism? If the blessings of freedom have sometimes been abused, it is because they are not well understood. Those occasional evils, which have happened in the infant state of liberty, are but the effects of despotism. Men have been long treated with inhumanity, therefore they are ferocious. They have often been betrayed, therefore they are suspicious. They have once been slaves, and therefore they are tyrants. They have been used to a state of warfare, and are not yet accustomed to universal benevolence. They have long been ignorant, and have not yet attained sufficient knowledge. They have been condemned to darkness, and their eyes are dazzled by light. The French have thrown aside the ritual of despotism, but they have not all had time to learn the liturgy of that new constitution, which is laid upon the altar of their country. But the genuine principles of enlightened freedom will soon be better comprehended, and may perhaps, at no distant period, be adopted by all the nations of Europe. Liberty may bring her sons from afar, and her daughters from the ends of the earth.

The oppressions which mankind have suffered in every age, and almost in every country, will lead them to form more perfect systems of legislation, than if they had suffered less; and they will only have to regret, that their happiness has been purchased, by the misery of past ages.

Then will the reign of humanity, of order, and of peace, begin; the gates of Janus will be forever closed; liberty will extend her benign influence over the nations, and ye shall know her by her fruits.”

But to return to ourselves.

Another blessing we enjoy, and which calls aloud for our gratitude, is the excellent constitution of our state government, and that of the federal system, which gives union, order, and happiness to America.

Few nations have ever enjoyed the opportunity, of taking up government upon its first principles, and of choosing that form, which is adapted to their situation, and most productive of their public interests and happiness. “The government of the United States,” says a political writer, 8 approaches nearest to the social compact, of any that history can furnish.” Upon an impartial examination of our constitution of government, we find it the best calculated for promoting the happiness, and preserving the lives, liberty, and property of the citizens, of any yet recorded in history. Liberty is here placed in the custody of the people. It wisely guards against anarchy, and confusion on the one hand, and tyranny, and oppression on the other. It is framed upon an extent, not only of civil, but of religious liberty, unexampled, perhaps, in any other country. The sacred rights of conscience are so secured, that “no citizen can be hurt, molested, or restrained in his person, liberty or estate, for worshipping God, in the manner and season, most agreeable to the dictates of his conscience, or for his religious profession or sentiments.” How should this consideration endear it to its citizens, and induce them to reverence it—not only calmly to submit to it, but to regard it with a veneration and affection rising even to enthusiasm, like that, which prevailed at Sparta, and at Rome.

Happy people, whose lot is fallen to them in pleasant places, and who have so goodly an heritage. Happy people! If we have wisdom and virtue, to improve aright the advantages we now enjoy. Blessed be God, who hath visited, and redeemed his people; who hath called them to liberty, and granted them the blessing of peace, and of a free government.

One other favour, you will permit me to mention, is our national prosperity. One blessing generally introduces another, and this is the consequence of peace, and a free government. Our swords are now turned into ploughshares, and our spears into pruning hooks. Our ships, instead of carrying the engines of destruction, are now fraught with the stores of the merchant, and convey to us, from all quarters of the world, the peculiar treasures of kings, and the provinces. The riches of the earth, and the abundance of the seas, are profusely poured into our laps.

But we are not, by an abuse of these blessings, in danger of being deprived of them? If, having eaten and become full; having built goodly houses, and dwelt therein; and having our silver and our gold, and all that we have, greatly multiplied and increased; instead of being thankful for these blessings, and temperate in the use of them, we become presumptuously lifted up, and forget the Lord our God; if, while we enjoy the highest degree of political liberty and prosperity, we are not a virtuous and religious people, shall we not provoke the Most High to withdraw these favours from us, and “to empty us from vessel to vessel?” If, instead of practicing that righteousness, which exalteth a nation, we indulge a spirit of self exaltation; what an army of evils will prevail with it? Luxury and excess supersede the enjoyment of the things themselves. Ostentation, in a great measure, supplants the true delights of society, and an emulous superiority in pride, and distinction, contributes materially to the utter annihilation of simple principles, and almost, cuts asunder the cords of genuine, sentimental friendship. The fate of nations confirms a very ancient doctrine of revelation, that whenever public prosperity causes a forgetfulness of God, a contempt of religion, and increasing profligacy, in the manners of a people, that very prosperity shall destroy them.

With this declaration, and with the many examples of its truth, recorded in the page of history, let us exert ourselves to perpetuate the great blessings, and privileges we enjoy, by a contrary demeanor, and a more Christian deportment than we have hitherto exercised: for the prolongation of our national charter is entirely dependent thereon; and the continuance of national prosperity is solely held, by this conditional tenure, the Lord is with us, while we are with him; if we seek him, he will be found of us, but if we forsake him, he will forsake us.

Nor are we in less danger, from the abuse of our civil liberty, than from that of our prosperity.

Civil government is, doubtless, one of the greatest external blessings, of which we are possessed. It is our protection from fraud and injustice—from rapine and violence. It is the security of our lives—of our property—of everything that is dear to us. The abuse of liberty is the greatest of evils, and draws after it, a train of the most baneful consequences. When a people misimprove their privileges, and become disorderly, ungovernable, and factious, they introduce a state of anarchy, which is worse than absolute despotism.

No one, of the least reflection, can be insensible, what great advantages that nation enjoys, which is not only in a state of perfect peace with its neighbours, but possesses uninterrupted quiet and tranquility at home; which is neither threatened with foreign insult, nor molested by inbred commotions, generally speaking far more dangerous than the former; at least, when they rise to any considerable heighth. It has, indeed, been said, that “small disturbances in the state, do the same service that the winds do in the air, by motion to keep it from stagnation and putrefaction:” But when once the winds are raised, no one can tell when they will be laid, or how strong they will grow; and that which was wantonly, or from selfish views, raised, to serve a present turn, may, in time, come to overturn a constitution.

We are not indeed to suppose, that every small inquietude, every little party or faction, that happens to take place, will be able to accomplish such extraordinary, such pernicious events; yet, it will not be disputed, but that they are liable to produce many fatal, and destructive consequences; which, though not always immediately apparent, will yet, in time, become sufficiently manifest, by a general corruption of manners, and by breaking loose from all proper restraint.

An ingenious writer 9 justly observes, “That a dangerous ambition oftener lurks behind the specious mask of zeal for the rights of the people, than under the forbidden appearance of enthusiasm, for the firmness, and efficiency of government. History will teach us, that the former has been found a much more certain road to the introduction of despotism, than the latter; and that of those men who have overturned the liberty of republics, the greatest number have begun their career, by paying an obsequious court to the people, commencing demagogues, and ending tyrants.”

How cautious, then, should we be, while we are zealous for liberty, that we do not despise government, and weaken the springs of it, by running into licentiousness. A spirit of faction, of murmuring and discontent, may excite internal discord, which may accomplish that, which external violence was not able to effect, I mean our independence, liberty, and safety.

We have no reason to doubt of the virtues, and abilities of those, whom our own free choice has made the guardians of our rights, both in the federal and state governments; we are persuaded, that their upright and faithful endeavours will be exerted to secure, and perpetuate the blessings of peace, and liberty, and to promote the true interest of this people. While the measures of righteousness are religiously observed in their administrations, we are sure, they will be crowned with success. For it is by righteousness, the throne of government is established, and the nation is exalted.

We have the happiness of seeing once more, at the head of this Commonwealth, a Gentleman, 10 of whose abilities in the arduous and important science of government—of whose patriotism and love of liberty—of whose integrity and upright intentions we have had long experience. That display of wisdom, fortitude, and magnanimity, joined with the most unremitting attention, and perseverance, manifested in the virtuous struggle, to obtain and secure our independence, must place his Excellency in the rank of those great and worthy patriots, who have distinguished themselves as the defenders of the rights of mankind: And the many and eminent services he has rendered to this Commonwealth, over which he has so often, and so long presided; as well as his many public and private virtues, add a lustre to his character. We sincerely lament, that the discharge of the duties of his high, and important station, is rendered so difficult and irksome, by his Excellency’s ill state of health, and the many bodily infirmities with which he has been long afflicted. May the benevolent Parent of the universe, who is the health of our countenance, and our God, remove the pains and disorders, under which his Excellency labours, restore and confirm his health, make the remainder of his days happy to himself, and useful to the Commonwealth, and finally reward all his services with eternal happiness in his kingdom above.

The patriotism, firmness, and inflexible attachment to the interests of his country, manifested by his Honor, the Lieutenant-Governor, 11 through a long series of years, justly entitle him to the second rank in government: And the great unanimity, with which his Excellency and Honor have, so repeatedly, been elected to their respective honourable stations, by the unbiased suffrages of their fellow-citizens, is the highest attestation of their merit. To the gracious protection of almighty God we commend them both; beseeching him to grant them wisdom from above; and grace to improve their distinguished talents, in promoting the true interest of this Commonwealth, and the United States.

The Gentlemen, who compose the two branches of the General Court, have, many of them, the satisfaction of reflecting, that their former services have proved acceptable to the multitude of their brethren, by their being re-elected into the important department of legislation. In filling up the few vacant seats in the Senate, and in choosing an executive Council, for the ensuing year, which is the first object of their concern, they will not be influenced by personal or interested views; but will elect such out of those, who are the subjects of their choice, as are able men; such as fear God; men of truth, hating covetousness.

It has indeed been doubted by some, whether this rule should, in all cases, be strictly adhered to; whether a man who is not of this description, who is not a man of rigid probity; who does not appear to have the fear of God before his eyes, and to be governed by a sacred regard to his laws, may not still, in a political capacity, be entitled to great merit, and be a proper person to be concerned in guiding the helm of state. Long experience in civil affairs, it is said—a superior knowledge of the laws—a facility of speaking and of dispatching business—the discovery of arts useful to government, are qualifications necessary to promote the good of the state, which is the main end of all government.

Perhaps we may allow of the exception, provided there is nothing in the personal character of such, from which the state may apprehend greater danger, or inconvenience, than it can expect good, from their capacity to serve it.

Still it holds good, that men of probity,–or virtue,–of religion ought, in all well regulated states, to be the objects of the people’s choice, both from the natural tendency of virtue to promote the happiness of a nation, and from the influence of a good example; which has, in persons distinguished by the confidence of their brethren, a sensible and powerful influence towards rendering religion and virtue more generally esteemed, and practiced. This consideration will have the greater weight, if we reflect, that (as we have shewn) most of the flourishing states in the world, have owed their origin and increase to virtue and righteousness; so, as the manners of the people grew more dissolute and corrupt, they gradually declined in power, in wealth, in credit.

It would be going out of my proper sphere, and perhaps invading the province of the Chief Magistrate, to enter into a detail of those objects, which claim the attention of the General Court, in their present or suture sessions, in the course of this year. Their own good sense, their political knowledge, and their perfect acquaintance with the internal state of the Commonwealth, will point out, and lead them to adopt such measures, as present exigencies require.

Our civil fathers, however, will permit me to remind them, that it is righteousness only which exalteth a nation; that it can never be good policy to transgress the sacred rules of justice and fidelity; and, that the grand secret of political wisdom is to maintain a steady and untainted integrity. They will, therefore, for the support of public faith and honour, as well as domestic tranquility, pay the strictest attention to commutative justice and equity, by a faithful observance and fulfillment of all public engagements; remembering that public contracts are as binding, as private ones can be supposed to be; and ought to be discharged with the same good faith and punctuality; and that no nation can make the least pretension to the character of a righteous one, that does not pay a sacred regard to its promises and contracts.

They will maintain inviolate, by a strict adherence to its original principles, our happy constitution of government; and, for the purposes of national happiness and glory, they will support and strengthen the federal government of the United States, by every constitutional means in their power; fully persuaded that the continuance of our national government is essential to our independence, our safety, our very existence as an empire.

Our civil rulers, will think themselves obliged, both in their public and private stations, to propagate a spirit of industry, frugality, and sobriety, among all ranks of people; to encourage agriculture, commerce and arts; and to promote the interests of literature and science; from the strongest conviction, that ignorance and liberty are incompatible; that the former is the parent of despotism, and the nurse of superstition. In fine, they will do all in their power, that wisdom and knowledge may be the stability of our times—that all vice and impiety be suppressed, and that the people may be allured to the practice of that righteousness, which exalteth a nation. In order to this, they will shew, in their own persons, that they are not ashamed of the gospel of Christ, by paying all due regard to his sacred institutions, and obedience to his laws.

Sensible of the difficulties of their task, and of their need of divine aid and support, we commend them to him, who giveth wisdom to the wise, and understanding to the prudent; beseeching him to direct and prosper all their consultations, to the advancement of his glory, the good of his church, the safety, honour and welfare of the people of this Commonwealth, and of United America.

Permit me to conclude, by reminding this whole assembly, that it concerns everyone to live in the practice of religion and virtue; not only as the public prosperity is deeply concerned in it, but as their own personal happiness, both here and hereafter, absolutely depends upon it. Godliness is profitable for all things, having the promise of this life, and of that which is to come. As therefore we wish the prosperity of our country; as we wish to enjoy the comforts of the present world; as we are anxious to meet the approbation of God, and to enjoy his favour in heaven; let us become the sincere disciples of Jesus Christ; let us follow peace with all men, and holiness, without which no man shall see the Lord. Let the recollection, that the eyes of God are against those who do evil, and of that indignation, which he will finally pour upon the ungodly, deter us from all iniquity, and lead us to aspire after their genuine piety, which will most assuredly, through the infinite merits and mediation of Jesus Christ, introduce us to the future vision and fruition of God, where we shall see him as he is, and know even as we are known.

Endnotes

1. Eccles. xii. 9.

2. Diodor. Siculus. Herodotus lib. 2.

3. Montague’s Letters.

4. Cicero de Harus. Refp. P. 183.

5. Cicero de officiis.

6. Machiavel.

7. Helen Maria Williams.

8. Paley.

9. Federalist.

10. His Excellency John Hancock, Esq.

11. His Honor Samuel Adams, Esq.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!