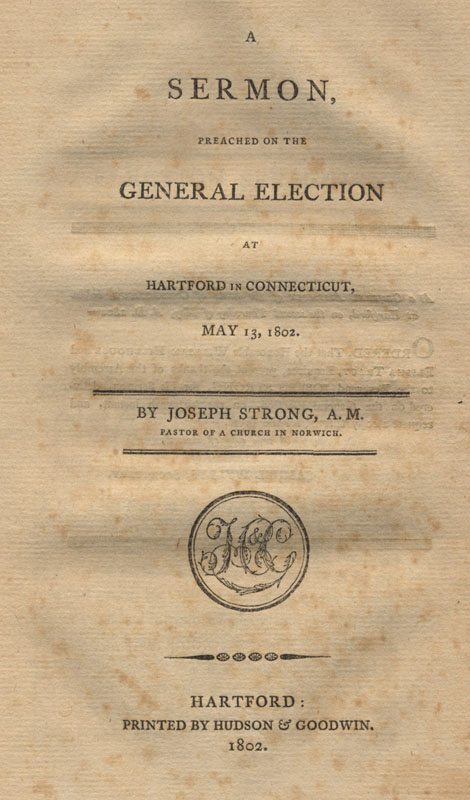

Joseph Strong (1753-1834), brother of Nathan Strong, graduated from Yale in 1772. He was the pastor of the 1st church in Norwich, Connecticut for fifty-six years. The following sermon was preached by Joseph in Connecticut on May 13, 1802.

SERMON,

PREACHED ON THE

GENERAL ELECTION

AT

HARTFORD IN CONNECTICUT,

MAY 13, 1802.

BY JOSEPH STRONG, A.M.

PASTOR OF A CHURCH IN NORWICH.

At a General Assembly of the State of Connecticut, holden at Hartford, on the second Thursday of May, A. D. 1802—

ORDERED, That the Honorable William Hillhouse and Elisha Tracy, Esquires, present the thanks of this Assembly to the Reverend JOSEPH STRONG, for his Sermon, delivered on the General Election, on the thirteenth instant, and request a copy thereof for the press.

A true copy of Record,

Examined by

SAMUEL WYLLYS, Secretary.

JEREMIAH, vi. 16.

Thus saith the Lord, stand ye in the ways and see, and ask for the old paths, where is the good way and walk therein, and ye shall find rest for your souls.

THE Jews were at no period in a more prosperous state on worldly accounts, than when Jeremiah commenced his prophetic labors. During the reign of Josiah, a prince highly accomplished both by nature and grace, the continuance of peace for a number of years had introduced plenty and ease; though not without being accompanied with more than an equal proportion of vice and dissipation. Added to the complete prostration of private virtue, each social tie, whether it respected God or man, was violently broken asunder. Thus situated, it was the dictate neither of God’s covenant love nor of that regard which he owed to the honor of his own character, to allow the existing state of things to continue uncorrected. The experiment of mercy having proved but too unsuccessful, every principle dictated that judicial infliction should be made its unwelcome substitute. Nothing remained to be done previous to such judicial infliction taking place, but to make solemn proclamation of the fact, accompanied with one more overture in favor of national amendment and safety. This delicate and arduous task was assigned to Jeremiah, a man exactly formed for the purpose in every view which can be taken of his character. Possessed of a mind constitutionally firm, his address was plain and forcible. He felt for all the interests of his country with ardor, though in subserviency to a far higher principle—disinterested regard to the prerogatives of Jehovah’s character and law. As might be expected from such a messenger, acting under the immediate direction of heaven, each branch of his address was, to an unusual degree, pointed and solemn. “O daughter of my people gird thee with sackcloth and wallow thyself in ashes; make thee mourning as for a son, most bitter lamentation. The bellows are burnt, the lead is consumed in the fire, the founder melteth in vain, for the wicked are not plucked away. Be thou instructed, O Jerusalem, lest my soul depart from thee; lest I make thee desolate, a land not inhabited. Thus saith the Lord, stand ye in the ways and see; and ask for the old paths, where is the good way, and walk therein, and ye shall find rest for your souls.”

The circumstances which dictated the text, being those now sketched, its more particular application to the present occasion, will naturally direct our thoughts to two enquiries:–

What are those paths pursued by our fathers, which in a more distinguishable sense constitute the good way:–And

The nature of that rest to be secured by walking in them.

In view of the proposed outlines to the present attempt, it is far from my design to amplify in indiscriminate praise of ancient times, at the expense of those which are modern. Forward to concede the fact, that the age of the fathers was marked with numerous foibles or even faults, at the same time it will be contended, that in view of all circumstances it was an age to a superior degree exemplary and respectable; it is therefore the joint demand of gratitude and interest, that we carefully select its virtues and copy them into our own practice.

While standing in the way to see, there is no old path which more clearly and forcibly strikes the mind than the confirmed belief of our fathers in the Christian scriptures. The fact is not to be questioned, that short of fifty years past, scarcely a single avowed infidel either disgraced or endangered this privileged part of God’s American heritage. Every voice was rather in union with that of the apostle, “Lord to whom shall we go, for thou hast the words of eternal life.” Good sense, accompanied with reverence for Jehovah, formed the prevailing character; and the Bible was seen to command universal and unwavering esteem. The wide departure from such an happy state of sentiment and feeling which has since taken place, is but too perceptible and ominous. Numerous causes have conspired to produce the wide spread of infidelity among us; causes which continue to operate, and that not without being much strengthened by the solicitude which ever marks party spirit, to support its own favorite cause whether right or wrong. The motives which excite the infidel to exertion, are injudicious and malevolent in the extreme. The great effort of his life is to prostrate a system which can injure no one, and if true, promises essential advantage to all. To leave out of view the solemn article of death, with all that may ensue, the Christian scheme of religion merits the highest esteem and most industrious encouragement. Both its doctrines and moral precepts are adapted to promote personal enjoyment, strengthen the bands of social intercourse, and reduce to consistency and order the discordant, deranged interests of the world.

Another of those good old paths, the subject of present enquiry, was an especial reference to the religion of the heart. Our fathers did not stop short with advocating a mere speculative religion, however rational and sublime; but superadded their confirmed belief of its inward, transforming influence. Morality was their frequent theme, though not to prevent its being a morality the fruit of pre-existing grace. Although such a trait in ancient character, may probably sink it in the esteem of some and even subject him who mentions it to the disgust and obloquy of those who take pride in their liberal modes of thinking, it ought and will be contended that experimental religion is a great and glorious reality. None ought to blush in mentioning its name or in urging it home to the heart. While in the case of the private citizen it forms an invaluable possession; to the Christian magistrate, it is in superior degrees necessary and advantageous. In exact proportion as the duties devolved upon him are weighty and arduous, he ought to cultivate an holy temper—place his supreme dependence upon God—and encourage the vigorous exercise of faith with respect to those rewards, which await the faithful servant. Are these remarks just, we certainly owe no thanks to those who are so forward at the present day to rationalize our holy and good religion. Too rational already for them to love it, their efforts re no better than disguised infidelity. While their professed object is to display its harmony and extend its popularity, they in fact do more than the avowed infidel to disorganize its parts and enfeeble its energies.

It may be proper, in this part of the discourse, also to remind you, how industrious our fathers were, to give existence and energy to moral sentiment. Wherever the sphere of their influence extended, they were forward to impress ideas of the divine existence and government—the ties of social relation—creature accountableness—and the solemn remunerations of eternity. They were under no apprehension of practicing undue influence upon the untaught mind. They did not conceive it an encroachment upon the rights of natural liberty, to prepossess the heart in favor of what is virtuous and useful. Foreign to the impressions of moral sentiment, the whole is put to hazard which constitutes well regulated community. Proper veneration for civil rulers is done with—good neighborhood ceases—the natural and powerful cement of families is destroyed—and the nearest connection in life treated with baseness and infidelity. As all must be sensible, the efforts of the present day that tend to such an unwelcome issue, are by no means small. In total disregard of the good example of the fathers, how many among us have the effrontery to circulate writings, and advocate them in private conversation, the avowed design of which is to prostrate all distinctions in life—reduce man to a state of nature—vacate the solemn rights of marriage—and surrender the dearest interests of human nature to the guidance of appetite and passion. Such is the boasted philosophy which closed the eighteenth, and is with too much success, ushering in the nineteenth century. A commendable regard to the future respectability of the age in which we lie, would almost prompt a desire that the powers for history were extinct—that no heart possessed the inclination of hand the ability to inform posterity, how base were the ideas and degenerate the practices of their fathers.

In this connection you will permit me to mention also, that spirit of social deference and subordination which strongly marked the age of the fathers. As for the fact, no person to a considerable degree advanced in life, will undertake to call it in question. Not to pain your feelings by a recital of what is now fact,–the time has been when children did not conduct as though they were compeers with their parents—when those covered with grey hairs were treated with reverence—when talents and literary improvement excited feelings of veneration—and when both legislative and executive office, were looked up to and obeyed as the institution of God. Let a selfish, equalizing spirit say what it may, society will never rise with regularity and firmness unless the feelings of rational subordination constitute its basis;–feelings rarely operative, provided they do not commence with childhood, gradually forming into settled habit with the increase of years. With mankind, more the creatures of habit than of sentiment, when the latter principle does not operate to the extent which might be wished, the good influence of the former is by no means to be rejected. The parent and schoolmaster do more to make the child a good or bad citizen, than the whole which can be done through the remainder of life. It must be a great force indeed, which bends the full grown tree into a new direction. Bent aright at first, very little after labor is required to mould it to that particular situation in the great political machine, where it is most needed. Those who do not early commence the habit of commendable subordination and respect for superiors, almost without exception, prove themselves restless, troublesome members of community. A turbulent, incendiary temper, being the character of the child, will not fail to operate when arrived to years of manhood. The ring-leader of quarrel and faction among his play-mates, is certain of being an high toned demagogue, to whatever department of life providence afterwards assigns him. These remarks are jointly supported by theory and observation. Beyond most others, the spirit in question is one which society ought seriously to deprecate. The evidence of history is explicit to the point, that numerous well regulated governments have lost their liberties with everything which mankind hold dear, by means of a single unprincipled, ambitious individual. Through the agency of intrigue or direct usurpation, they have thus in a day exchanged the brightest national prospects for the chains of unqualified slavery. There is no kind of government which more loudly reprobates this spirit, than what ours does. For though a republican government gives opportunity for the exercise of the fiery, uncontrollable spirit, yet the genuine principles of such a government are opposed to its existence.

Another noticeable fact, with respect to our fathers, was their strict adherence to the principle, that none ought to be elevated to public office except those whose opinions and behavior were strictly Christian. Brilliancy of talents was a secondary consideration in their view, when accompanied with an unprincipled heart. What confidence can the public mind reasonably place in men who spurn our holy religion and sanguinely calculate upon death as the termination of existence? Except that feeble principle the fashionable world stiles honor, what stimulus have they to the regular and useful performance of those duties made incumbent by office? With respect to such persons, in what consists the obligatory strength of oaths? The idea of future accountableness laid aside, an oath instantly dwindles to a mere cipher.—A not less weighty class of objections are adduceable [to bring forward in argument or evidence] against the scandalously immoral than against the avowed infidel. Elevated to office, the influence of example never fails to be doubly impressive. To emulate and copy high life is inseparable from human nature. Beauty and deformity of character in the peasant or beggar, strike the mind in a very feeble manner, compared with what they do when attached to the rich and powerful. Clothed with the purple, vices the most base and odious, by a kind of magic influence, become completely fascinating;–there being nothing more certain than that the libertine magistrate, from whom the whole evil has originated, will not do anything to correct it either by the enacting of laws or their after execution. It is hard to conceive how the friends of society, and especially those who profess themselves Christians, can give their suffrage for men of the above description. Conscience must have had administered to it some soporific draught, or it could not be the case. Though it be a conduct which nothing can justify, two causes may assist to its explanation;–the rage of party spirit, and the base arts of electioneering. Nearly without fail do these two great scourges of community act in conjunction. Beyond most other circumstances, political controversy has a powerful operation to call into exercise the irascible, violent feelings of human nature. Rational, calm thought laid aside, a wide opening is made to misrepresentation and seduction. Those are never wanting whose highest gratification consists in poisoning the public mind, and warping it aside from the advancement of its great and permanent interests. The advancement of some pecuniary interest, through more commonly a wish to rise into office, is the stimulus to such an insidious, contemptible line of conduct. A people must have lost their native good sense, when they cease moist heartily to despise the electioneering candidate. Persons who will adopt and persevere in such a line of conduct, ought to be unfailingly viewed with disapprobation and disgust. They affront the discernment and impartiality of their fellow citizens, and in the place of a rightful claim to promotion they only deserve contempt and frowns. The honorable name freeman is most improperly applied to the one, who ceases to follow the dictates of his own unbiased judgment and surrenders himself the tool of unprincipled intrigue. When we consider who are the individuals upon whom such intrigue is commonly practiced, it is matter of surprise that its effect is not more extensive and ruinous. However good the intentions of the middle and lower classes of society, their habits of life and want of correct information upon numerous political subjects, greatly expose them to deception. The address made to their passions finds no corrective influence from the quarter of judgment. Although till of late, this state has exemplified nothing of the evil which is the subject of present remark; it now fast gains ground, and is an omen dark to our future weal, and of course makes loud demand for vigorous opposition, from argument, example and law. The growing venality which marks elections is a circumstance which beyond most others, strongly indicates a premature old age to these American states. A most desirable matter would it be for this state, might it reassume its former dignified ground with respect to free, unbiased suffrage, before such reassumption is rendered additionally impracticable.

It merits to be further remarked with respect to the good way which our fathers pursued;–that they did not manifest an inclination constantly to innovate upon the established government. Both men and measures commanded their approbation and support, so long as nothing was discoverable unprincipled in the one, or essentially defective in the other. The correct political maxim no doubt had full possession of their judgment, that a less perfect form of government is preferable to one more studied and nicely balanced, that fails in the important article of execution. The fallacy of theory is in no instance more glaring, than with respect to plans of national government. The statesman often exhibits what appears consistent and beautiful upon paper which in course of carrying it into effect does not fail to produce the speedy and complete ruin of empire. A greater chimera was never imagined, than that a single form of government admits of universal application. It is the unquestionable right of every nation to adopt what kind of government it pleases; but the great point is that its principles be adhered to with firmness and its duties fulfilled with punctuality. How fortunate would it have been, for the fairest portion of Europe, which in course of a few years past, has exhibited a strange and most forbidding spectacle to the world, had its citizens felt the unquestionable justice of these remarks and conformed to them in practice? Mad with theory—infatuated by a spirit of overturn, they exchanged evils which required redress for those still more pressing and to be deprecated. Has the daring enterprise of an individual, given a successful check to such a state of things, and from a chaos of confusion and tyranny produced a degree of national order and energy in government, the example, notwithstanding, is worthy of universal notice and improvement. It teaches nations to appreciate a settled order of things, to dread innovation, and to cling to their constitutional chart with increased gratitude and strength of attachment. None but essential and glaring defects, ever authorize experiment upon the forms, and much less upon the principles of established government. A pillar removed is never easily replace, and how often is it fat that the removal of a single pillar exposes the building to certain and speedy destruction. The hazard thus incurred is often immense, yet there is no circumstance of national exposure to which the feelings of our nature more directly and forcibly impel. Passing by all adventitious circumstances, it is a radical propensity of the human mind to dislike government. It implies the relinquishment of certain rights, for the more perfect security of others. It calls for partial sacrifice to a common interest, that the vigilance and energies of that interest may give freedom of exercise and permanency to those private rights which are retained. To comply with the social compact which is a dictate of the judgment, involves no small share of self-denial. Owing to the restless temper of man, his constant effort is to independence and self-direction. Hence the frequent efforts made, to counteract the constitutions of well regulated society. Notwithstanding the numerous advantages derived from governmental association, those restraints and burdens it is under necessity to impose, have a direct tendency to excite the calumny or more daring opposition of licentious and ignorant men. And how perfectly do these remarks, inferable from the structure of human nature, coincide with our own observation? The person who has noticed the progress of things in these states for a number of years past, cannot fail to approve their correctness. Under various disguises, the effort has been constant to undermine our excellent constitution;–a constitution of government equally the work of necessity and wisdom; and no other evidence is requisite in its favor, but the unexampled prosperity of the country during the whole period since it began to operate. Inauspicious to the success of any constitution however good, as the past convulsed period has been, ours has succeeded to a wonder. There is no class of citizens but what has been remarkably smiled upon, under its auspices. The three great component parts of American society, the farmer, merchant and mechanic, must fight against their own interests, provided they calumniate its principles or endeavor to enfeeble its energies. Are certain burdens necessarily attached to all governments, for the various purposes of their own support, and the furtherance of justice upon the great scale, ours has much the fewest of such burdens of any government throughout the civilized world. It deserves serious thought, which is preferable, such comparatively small burdens, or the complete prostration of all constitutional authority. Where there is no form of government in operation, and of consequence no law, the state of things cannot be otherwise than unfortunate in the extreme. A country which has experienced so much of divine beneficence, in baffling the plots of foreign enemies, ought to be very cautious not to lay violent hands on itself. Such is clearly the joint dictate of commendable gratitude to the Father of all mercies and of a principle of self-preservation. Smiled upon as our national affairs have been for many years, they are not at present beyond the reach of essential and permanent detriment. Continuing to be divided among ourselves, the whole which mankind hold dear is put to hazard. The order of society will of course be deranged,–our liberties may be wrested from us—our morals are certain to depreciate even below what they now are—while triumphant infidelity is but too likely to assume the place of godliness.

It will only be further remarked of the fathers, that they were powerfully actuated by a love of their country. Many circumstances conspired to awaken and give energy to such a principle. The persecutions which prompted their removal to this land—the multiform hardships and dangers which marked distant establishments in a savage country—and the constant effort made to abridge, or wholly vacate their charter rights, gave increased strength to feelings constitutional in the human mind. Attached to the parent state by strong ties, they still at no period shewed themselves forgetful that they had a country of their own. Benevolent and just to all, their views and exertions were at the same time, to a degree, local. They felt and conformed to those high obligations which they were immediately under to themselves and to their posterity. How fortunate would it have been for us as a nation, had the same love of country operated with equal force at a more recent date? Foreign attachments have been one principal source of the numerous embarrassments under which we have and do continue to labor. Hence in particular those violent party animosities, which cannot be either denied or excused. For the citizens of an independent nation to attach themselves with warmth to the views of this or the other country, is equally servile and impolitic. The real point both of dignity and interest lies here, to remember that we are Americans, and prove ourselves equally independent in conduct, as in name. May it not be hoped that the late pacification among the contending nations of Europe, will operate to extinguish party spirit and consolidate our union upon the broad basis of harmonized views, feelings and exertions?

A few remarks upon the closing paragraph of the text will complete the present attempt. “And ye shall find rest to your souls.” The nature of this rest admits no question. Intimately related as the good behavior of the present life may be to the rewards of eternity, this is not the principal object of the passage now under review. Its primary reference is to those worldly advantages which are national. The whole extent of life often fails to realize the rewards of private virtue; but those of public, national virtue are never thus distant. The natural course of things, seconded by the promise of Jehovah, insures the event “that righteousness exalteth a nation.” Nations are often exalted, as the result of divine sovereignty, foreign to their own good behavior, yet such exaltation is most commonly judicial and greatly insecure as to its permanency. How far our national exaltation is of such a character demands careful enquiry. Upon whatever principle we account for the fact, the allotments of providence to us as a nation have been without example. The ground we now occupy, in some points of view, is elevated and commanding, though not to supercede a laudable wish to advance still higher. However eligible our present situation, it leaves room for much improvement. Did we pursue the good ways which our fathers trode, with that industry which their example recommends; each interest of our country whether natural or moral, literary or political, would be essentially advanced.

Agriculture connected with a growing population—mercantile enterprise—the arts and sciences—industry and economy through all the various classes of society—energetic government, and the wide diffusion of united views and exertions with respect to national interests, could not fail to form the result. With fervent piety and good morals added to these circumstances, it is hard to conceive what further internal improvements a people could wish. The principles of happiness and prosperity among themselves being thus firmly established, they may safely calculate upon “sitting under their own vine and their own fig-tree, with none to make them afraid.” And in view of this sketch of “rest to the soul”—of national emolument, aggrandizement and security, who of us but must feel grateful that it has been already so far realized, and who will refuse solemnly to pledge all his future exertions for its completion? In a superior degree indebted to a sovereign all-gracious providence for public blessings, yet we cannot ensure to ourselves their future continuance unless through the instrumentality of personal exertion. Means and the end are as closely connected in the civil, as in the natural world. Not an individual who assists to compose community, fails to have numerous and weighty duties devolved upon him for the promotion of the general weal. While moral and religious principles should never be out of view, as a stimulus to action through the different grades of society; each grade ought to study and carefully adhere to its own particular department of action. The private citizen ought to be in the habit of industry, punctuality in dealing, and submission to constituted authority. Those who minister at the altar must study uncorruptness of manners, purity of doctrine and the whole fervor of zeal in the best of causes. Those in executive office, should be equally careful never to overleap the boundary of law, or see its requirements trampled under foot with impunity. In the judicial department, an high regard to law and justice must never be subordinated to party interest or a fear of rejection from office. With respect to the legislator, his ideas upon every subject which comes before him ought to be correct, his views superior to the influence of local attachment, his firmness too great to be shaken by the strong collision of party, and his integrity bottomed upon a good heart. With the body politic thus classed, each one confining himself to his own proper province, order and perpetuity are certain to constitute its great prominent features. Peculiarly privileged in this state from the proper combination of these various social powers, we are probably not more indebted to either of them, than to a wise and upright legislative magistracy. From the first establishment of Connecticut to this day, a large proportion of those annually chosen to legislate, have no doubt, to an happy extent, exemplified the character of the good ruler drawn by the pen of inspiration, “The God of Israel said; the rock of Israel spake unto me, he that ruleth over men must be just, ruling in the fear of God. And he shall be as light of the morning when the sun riseth, even a morning without clouds; as the tender grass springing out of the earth, by clear shining after rain.”

Under an impression that the public suffrage, the current year, has fallen upon characters not less meritorious than those who have possessed the same honorable designation;–may I be permitted to recommend and urge, that they recollect with care and adhere with firmness to that general system of policy, which has rendered this state, for nearly two centuries, united and secure, prosperous and respectable. With the past thus a model for future procedure, the demand is direct and forcible, that science and religion should continue to command the liberal patronage of the civil arm. Fostered by legislative aid, they are certain to make large remuneration for all the pains and expense. A treasonable wish to enfeeble and ultimately prostrate the varied interests of community, can in no way be so easily corrected, as by the diffusion of knowledge and the sentiments of piety. Good principles and an immoral behavior sometimes incorporate, yet as a general rule the corrective power of the former over the latter is great. There is no so eligible mode of discouraging vice, as by a marked preference in the laws in favor of virtue. While wise and upright legislators duly appreciate these foundation principles, and encourage a spirit of reliance upon Jehovah for his special direction, it may be calculated with confidence, that they will legislate well, and should on no account fail to live in the hearts of a grateful people.

Without confidence in government, it cannot fail to sink into contempt and all the unhappiness of enfeebled operation. Few greater blessings are there than good rulers and good laws;–though let it not be forgotten that they form a blessing which subjects may realize or reject as they please. I have no doubt as a general fact, it is more the fault of the people than of the ruler, that their expectations from government are not answered. With that mutual confidence between those who govern and those who are governed, which ought to prevail, no essential interest would be put to hazard; tyranny and anarchy would be kept at an equal remove; and by a close combination of views and exertions, each interest whether private or public, individual or social, would rapidly progress to its greatest possible extent.

Under the special direction of a sovereign, holy providence, may such prove the future lot of this particular state and of those connected states, which assist to compose our growing and respectable empire! Wise for ourselves, as it could be wished we were, the prophet’s flattering anticipation in view of his beloved country, would not be either too sanguine or flattering in view of our own, “Thine eyes shall see Jerusalem a quiet habitation, a tabernacle that shall not be taken down. Not one of the stakes thereof shall be removed, neither shall any of the cords thereof be broken. But there the glorious God will be unto us a place of broad rivers and streams; wherein shall go no galley with oars, neither shall gallant ship pass thereby. For the Lord is our judge, the Lord is our lawgiver, the lord is our king, he will save us.”

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!