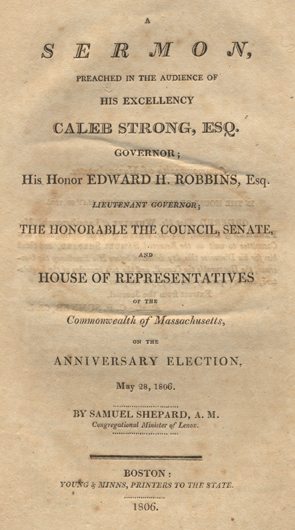

Samuel Shepard preached this election sermon in Boston on May 28, 1806.

SERMON,

PREACHED IN THE AUDIENCE OF

HIS EXCELLENCY

CALEB STRONG, ESQ.

GOVERNOR;

His Honor EDWARD H. ROBBINS, Esq.

LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR;

THE HONORABLE THE COUNCIL, SENATE,

AND

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

OF THE

Commonwealth of Massachusetts,

ON THE

ANNIVERSARY ELECTION,

May 28, 1806.

BY SAMUEL SHEPARD, A. M.

Congregational Minister of Lenox.

BOSTON:

YOUNG & MINNS, PRINTERS TO THE STATE

1806.

IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES, May 28, 1806.

ORDERED, That Mr. Wheeler of Lanesborough, Mr. Parkman of Boston, and Mr. Smith of West-Springfield, be a Committee to wait on the Reverend Samuel Shepard, and thank him for his Discourse this day delivered before His Excellency the Governor, the Honourable the Council, and the two branches of the Legislature, and to request of him a copy for the press.

Attest. C. P. SUMNER, Clerk.

I. CHRONICLES, XXIX. 12.

BOTH RICHES AND HONOUR COME OF THEE, AND THOU REIGNEST OVER ALL; AND IN THINE HAND IS POWER AND MIGHT; AND IN THINE HAND IT IS TO MAKE GREAT, AND TO GIVE STRENGTH UNTO ALL.

TO the pious mind the most substantial consolation is afforded by the consideration that there is a God. In his works, his providence, and his word there is abundant testimony of his being and attributes. It is no less pleasing to the good man, surrounded with dangers and in the midst of foes temporal and spiritual, to reflect that God extends his providential care to things of this world, and that the Most High ruleth in the kingdoms of men. David ascribes every event to the interposing hand of Divine Providence. Although from a humble station he was raised to a throne, and commanded in an eminent degree the affections and obedience of a nation truly great and respectable; yet he did not forget his dependence on God, nor deny his universal and particular providence. From the chapter, which contains the text, you will listen to his devout acknowledgment. “Thine, O Lord, is the greatness, and the power, and the glory, and the victory, and the majesty: for all that is in heaven and in the earth is thine; thine is the kingdom, O Lord, and thou art exalted as head above all. Both riches and honour come of thee, and thou reignest over all; and in thine hand is power and might; and in thine hand it is to make great, and to give strength unto all.”

God is to be seen in the production of all things animate and inanimate. He is to be seen in everything above and below us, within and around us, heard in the voice of every creature, felt in every motion, and read, in short, on every page in the great volume of the universe.

No less evident is it, that he, who created, superintends all the works on his hand. He, who “spake and nature took its birth,” does by the agency of his almighty arm continually uphold all things in existence. Should that power, which first caused them to exist, be withdrawn one moment, they would sink into nothing. It is impossible in the nature of things that a creature should be so made as to exist, one moment, in any respect independently of the Creator. If it might thus exist now, it might have so existed at first. If it might cause itself to exist now, it might have so existed at first. If it might cause itself to exist from one moment to another, it might have caused itself to exist from the beginning; and so a Creator would have been unnecessary. Everything, therefore, must be as really and as much dependent on the Deity for continuance in existence as for its first existence.

All things which exist, from the greatest to the least, are not only constantly upholden by the same power, which first gave them existence, but, in all their motions, actions, and changes, are under the care and direction of Divine Providence. He who first created all things for the best of purposes, so directs and disposes of everything, as, in the best manner, to answer those purposes.

It is true, all things in the course of God’s providence take place according to the laws of nature. The sun warms, and the showers refresh the earth; consequently, vegetation springs forth, and food is furnished for man and beast. This, it is said, takes place according to the course of nature. The hand of God, however, is in all this; for this course or law of nature is only the way, in which God constantly and regularly exerts his power and manifests his goodness. Notwithstanding the vital heat of the sun and the refreshing showers of heaven, the earth would produce nothing without the divine agency. These elements have no strength, in themselves, to cause even a spire of grass to grow. The laws of nature, therefore, by which things take place in a regular, stated manner, are only the way or course which God pursues in exerting his power and manifesting his goodness: so that what are called second causes have no power or efficacy in themselves aside from the immediate exertion of divine power, which is the proper efficacious cause of all things.

In the exercise of divine providence some events take place by the more immediate energy and agency of God; and others, by the instrumentality and agency of creatures, and by various mediums and what are called second causes. But in all events of the latter kind, the divine power and agency are as really and as much exerted, and are as much to be acknowledged, as if no instrument, agent, or second cause had been used: because, the creature or instrument has no power to act or effect anything which is not given by God himself.

This is the light, in which divine revelation everywhere represents the providence or government of God. It extends to all creatures, events, and circumstances throughout the immensity of the divine works.

In this view of the passage before us we may remark, that God’s providential government respects all things in the natural world. The heavenly bodies, in all their movements, revolutions, and changes, are under his direction. The “ordinances of heaven” are established by his hand, and the “dominion thereof” set in the earth. “The all-perfect hand that pois’d, impels and rules the steady whole.” This causes the sun to pour on us his vital heat, the moon to cheer the solitary night, and moves the comets, which blaze through the vast profound, and fill the astonished world with awe! To God we owe the grateful succession of the seasons, and under his providence we enjoy the fruits of the earth. He giveth us “the former and the latter rain,” and causeth the earth to yield her increase in plentiful measure. He maketh his paths to drop marrow and fatness on the pastures of the wilderness, and the little hills to rejoice on every side. He clotheth the hills with flocks and the vallies with corn. He taketh care of our lives and health. Protected by his hand, they that go down to the sea in ships and do business on the great waters survive the dangers, which surround, and threaten to swallow them up. They experience the goodness of God and behold the wonders of his hand, which, at any time, bringeth prosperity to our commerce and fishery, and causeth the heart as of the mariners to rejoice; for, he holdeth the winds in his fists and the storm and tempest obey his voice. “He shutteth up the sea with doors, and saith, hitherto shalt thou come, but no further; and here shall thy proud waves be stayed.” God’s providence extends to the brutal world. He provideth not only for the higher orders of his creatures, but he openeth his bountiful hand, and supplieth the wants of every living thing. “The young lions roar after their prey, and seek their meat from God.” He provideth for the ravens their food, and giveth to their young ones when they cry. The cattle on a thousand hills are fed by his hand. How numerous and various the tribes of living creatures, which inhabit every part of the material world! Every leaf, every particle of water, every breath of air teems with life: yet, not a particle of the ocean, not a leaf of the forest, not a ray of the sun moves without his direction. Not a sparrow falls to the ground without the agency of God, and the very hairs of our head are all numbered. In short, we may contemplate the divine hand in the movement of a world and in the movement of an atom.

God reigns in the moral world. His providence assigns to the unnumbered hosts, which surround his throne, their several stations. Their employments are all marked out by the same providential hand, and strength and assistance are afforded them according to their respective labours. The hearts of all flesh are in his hand. He causeth the wrath of man to praise him, and the remainder of wrath he restraineth.

God ruleth in the political world. His providence regardeth all the nations of the earth. One nation falleth and another riseth, because the Lord commandeth it. His word decideth the fate of empires, and he giveth them to whomsoever he will. His hand directeth the storm of war and decideth the victory. In the tumults of Europe, at the present day, his providence is to be regarded. Combined armies go forth in vain, unless the Lord be with them. He can render their counsels vain, and, by sending among them discord, or famine, or disease, can either divide, or destroy their strength. Whatever be his designs in the convulsions, which are taking place among the civil kingdoms of this world, surely he will, in his holy providence, accomplish them all.

To the considerate mind it affords the sublimest pleasure, that a God of infinite power, wisdom, and goodness, taketh the disposal of all things into his own hands, and superintendeth throughout his vast dominions. Should he cease to do this, universal disorder and confusion would ensue.

The harmony of heaven would soon give place to discord and dire confusion. Even angels themselves would lose all subordination. Order would press on order, and rank on rank, and the throne of God would shake amid the wild tumult.

Those orbs which now roll harmonious through the expanse of heaven, undirected by the hand of God, would rush upon each other, or wander from their courses into the fields of infinite space.

And, here on earth, what would be the rage and tumult, were the superintending hand of Divine Providence once withdrawn! Who would make the seasons regularly revolve? Who would give us seed time and harvest? Who would restrain the wrath and fury of man, and dispose the nations to peace? Alas! destitute of the restraints of the Supreme Ruler, nation would rise up against nation, man against man, brother against brother, and more horrid scenes of barbarity and outrage would be experienced, than language can describe, or imagination conceive.

Such would be the dreadful effects, should God cease to exercise his providence over his works. In his providential government, therefore, ought not every heart joyfully to acquiesce?

No one seemed more ready to acknowledge the fitness and propriety, yea, the absolute necessity of God’s superintending his works, than David. In all things he contemplated God, and saw him in every event. He knew that, to God’s sovereign disposal, he was indebted for all his greatness, his riches, and his honours, and, in all his ways, he devoutly acknowledged God as the Supreme Ruler of the universe. This appears not only from the text and its connection, but also from other passages of scripture. “No king,” saith he, “is saved by the multitude of an host: a mighty man is not delivered by much strength. An horse is a vain thing for safety: neither shall he deliver any by his great strength. Behold, the eye of the Lord is upon them that fear him.”

Contemplating the subject in this light, we may, with propriety, notice some things in divine providence respecting the Israelites; things, to which David probably referred when he said, “in thine hand is power and might; and in thine hand it is to make great.”

God gave to the people of Israel a good land. It abounded in the necessaries and comforts of life. It was the land of promise, which God gave to Abraham and to his seed. They were blessed not only with a soil which was fertile, a climate which was temperate, and air which was salubrious; but with a country, the natural situation of which was favourable to national peace and safety. A beautiful description of it is given us in Deuteronomy. “The Lord thy God bringeth thee into a good land; a land of brooks of water, of fountains, and depths that spring out of vallies and hills; a land of wheat, and barley, and vines, and fig trees, and pomegranates; a land of oil olive and honey; a land wherein thou shalt eat bread without scarceness, thou shalt not lack anything in it; a land whose stones are iron, and out of whose hills thou mayest dig brass.” In another description of it, the Israelites were told that it was a land which the Lord their God cared for; and, that the eyes of the Lord their God were always upon it from the beginning of the year even unto the end of the year. The Israelites, therefore, were peculiarly favoured in the enjoyment of those means, which are afforded to any nation, by a good and fruitful country, of becoming rich and prosperous, great and happy.

They were also blessed with an excellent constitution of government. It is sometimes called a Theocracy; but excepting some particular acts of royalty, which God reserved immediately to himself, it was, in its visible form, and as originally committed to the administration of man, republican. Opposed to every system of tyranny and oppression, it was well adapted to secure and perpetuate the rights and privileges of every member of the community. If the Israelites were not a free and independent people, the fault was in themselves. To the distinction, freedom, and independence of each tribe, their agrarian law was peculiarly favourable. In each province, all the freeholders must be not only Israelites, but descendants of the same patriarch. The preservation of their lineage was also necessary to the tenure of their lands. The several tribes, while they were united as one commonwealth, still retained their distinction and privileges, and were independent of each other. Each tribe was in a sense, a distinct state, having its own prince, elders, and judges, and at the same time was one of the united states of Israel. They had, also, a national council. This, which might with propriety be called a general congress, was composed of the princes, the elders, and heads of families from all the tribes. It was the business of this assembly to attend to all matters, which related to the common interest; such as levying war, negotiating peace, providing for, and apportioning the necessary expenses of the nation, and deciding in matters of dispute between particular tribes. No one tribe had a right of dictating to, or exercising superiority over another. In this grand national assembly, resided the highest delegated authority, and it was to be regarded by all the tribes with the greatest reverence. A violation of the constitution, in this respect, subjected the offenders to the most severe penalty. This grand council of the nation had its president, who was constituted such upon republican principles.

Happy had it been for the Israelites, if they had not eventually changed their form of government, and desired a king. By their folly and wickedness, in so doing, they lost many of their ancient privileges, and were brought at last under the iron yoke of despotism.

The Israelites were favoured with just and righteous laws. Their government, therefore, when duly administered, was a terror to evil doers, and a praise to all who did well. It was founded in righteousness, and the laws were executed with fidelity, every member of the commonwealth was secure in his rights and privileges.

The people of Israel were also distinguished above other nations, kingdoms, and states, by their system of religion. Its outward service was indeed attended with some burdensome rites and ceremonies; but these were wisely instituted in condescension to their weakness, or with a view to guard them against idolatry, or to lead them ultimately to the great sacrifice for sin, without which there could be no forgiveness. The being and attributes of God, the worship which would be acceptable to him; in short, all the duties incumbent on them, as subjects of moral government, towards God, their fellow creatures, and themselves, were forcibly inculcated in their religion, and it tended to make them wise, virtuous, and happy.

Equal reason have we to notice particularly some events in divine providence towards us as a nation. We inherit a pleasant and fertile country. Planted in a land equally distant from the frozen regions of the north and the burning sands of the south, we are furnished from our own soil, with all the necessaries and some of the delicacies of life. The air which we breathe is mild, temperate, and salubrious. The soil which we cultivate easily yields to the labour of the husbandman, and richly rewards his toils. We are not doomed to cultivate the rocky mountains of Switzerland and Norway, nor to glean a scanty subsistence on the barren plains of Arabia. Our natural situation, separated as we are from other nations by intervening oceans, is favourable to peace. Variegated with hills and vallies, and intersected with rivers and seas, our country is possessed of the greatest possible advantages for agriculture and commerce. There is no people in the known world so amply supplied with the necessaries of life from their own native soil as we are, and, at the same time, under such advantages to furnish themselves with all the luxuries of other climes.

We are favoured with a good constitution of civil government. When our land had been drenched, for seven long years, with the blood of our brethren, and fire and sword had made desolate some of our largest towns, God commanded, and the thunder of war ceased to roar, the blood of our brethren ceased to flow, and peace returned to bless an exhausted country. Joy was now on every countenance, and in every mouth thanksgiving and the voice of melody. But soon began we to feel the miseries of a weak and feeble government. Our commerce was shackled, our flag insulted, and our agriculture discouraged. Then the Most High appeared for us, and enabled us to devise, and united our hearts to accept, a form of government, which to this day, diffuses blessings over the union. Soon did we feel the good effects, which resulted from our excellent civil constitution. Our commerce was extended, our agriculture was encouraged, our publick credit was raised out of the dust and placed on a firm basis, our name became respectable among the nations, and wealth flowed in upon us as an overflowing stream.

Thus, as a nation, have we, in a season of prosperity, been rising in greatness and affluence. While the nations of Europe have been involved in the horrors of a most bloody and distressing war, it has been our lot to enjoy the blessings of peace and a good civil constitution, and, in a sense, to rise on their ruins.

We are governed by laws made by ourselves; laws, which, while they operate for the good of the whole, tend also to the security of each individual. Under an arbitrary government, there may be some security to the subject in rights and privileges. He may not be defamed, nor assaulted by his fellow subjects, without some protection from the laws. His security, however, may not, in these respects, be such as the publick good requires. Tyrants may suspend the execution of laws at their pleasure; laws, most essential to the security of the life of the subject. More dreadful still is a state of anarchy, in which anyone may, unrestrained, insult and abuse, torture or take away the life of another. Happy for us that we have laws well calculated to restrain the unreasonable and licentious, and magistrates of our own choice for the punishment of transgressors.

In a state of nature, our rights and possessions would be very precarious. To secure these, is one great end of civil government. The sanction of law is necessary to their security. In this respect, we have been by Divine Providence peculiarly favoured, and we are under the strongest obligations to transmit to future generations those just and equal laws, which so eminently secure us in the enjoyment of life, liberty, and property; laws, that tend to promote the practice of those virtues which are conducive to the happiness of the community, and to suppress those vices, which insure its destruction.

Our religious privileges are singularly great. In this land the principles of religious toleration are generally understood and embraced, and the rights of conscience and inquiry are held peculiarly sacred. Here the light of the glorious gospel shines with meridian lustre; and, without this,

A savage roaming through the woods and wilds

Rough clad, devoid of ev’ry finer art

And elegance of life. Nor happiness

Domestick, mix’d of tenderness and care,

Nor moral excellence, nor social bliss,

Nor guardian law, were his;

Nothing save rapine, indolence and guile,

And woes on woes, a still-revolving train!

Whose horrid circle had made human life

Than non-existence worse: but taught by this,

Ours are the plans of policy and peace,

To live like brothers, and conjunctive all,

Embellish life.”

Think on the vast destruction of property in the recent war between France and the combined powers. Think on the almost incredible labour and fatigue endured. Think on the quantity of blood which has been spilt, and the number of lies which have been lost. Think on the agonies of the vast numbers who have lingered out their lies in consequence of wounds, or, what is still more dreadful, have perished by famine. Cast up the vast account of human wretchedness and misery caused by this one unhappy war, and how great is the amount! But what is this one war! What, in comparison with all the wars which have afflicted mankind from the earliest ages down to Bonaparte! Wars, infinite in number, and, in cruelty and barbarity, almost incredible! But the exercise of benevolence among nations and individuals would have prevented all these, together with all that astonishing and unknown amount of human wretchedness and misery accompanying them. The excellency of this principle of the gospel, which we have been contemplating, is, therefore, invaluable. Were it to prevail universally, Eden again would blossom, and Paradise return to bless the earth.

For the peaceable enjoyment of this religion and its institutions, our fathers bade farewell to their native land, and came to these western climes. The providence of God was remarkable in their preservation and settlement. Although, in some instances, chargeable with error and misguided zeal, yet they were an enterprising and virtuous people. They served God much better than we do. From their native land they brought with them the love of civil and religious liberty. In what they did, they sought the welfare of the community as one family. They sought the good of posterity. Forests were subdued by their hands, and towns were incorporated. The object of their social intercourse was mutual benefit. They instructed their children, and remembered the Sabbath day to keep it holy. They duly respected those who were appointed to rule over them. The ultimate design of their every movement was to promote that righteousness, which “exalteth a nation.” By their wisdom and piety, we, under God, enjoy many invaluable privileges. In these, we are to acknowledge a superintending Providence; for, who maketh us to differ? To differ from the poor and distressed; from those who wear the chains of slavery; from those whose ears are stunned with the din of arms; from those whose eyes are constantly pained with the sight of blood? The answer is at hand. Hear it, admire, and adore! “Thine is the kingdom, O Lord. Both riches and honour come of thee, and thou reignest over all; and in thine hand is power and might; and in thine hand it is to make great, and to give strength unto all.”

The Most High ruleth in the kingdoms of men. He exalteth, and he bringeth low. In the rise and fall of states and empires, in ages past, his providence has been concerned. By his care, our fathers were planted in this land. When they were brought to the brink of destruction, he made bare his arm for their salvation, and was as a wall round about them. Gradually he drive out the heathen before them, enlarged their settlements, and increased their numbers. He hedged them in on every side. And, in later times, when attacked by the whole power of the British monarchy, and this while in an unarmed and defenceless state, how signal were the interpositions of his providence for our protection! He inspired us with unanimity and fortitude. He sent us military stores from the very ports of our enemies. He blessed and succeeded our enterprises. He enabled us to detect and to baffle the counsels of our enemies, and raised up and qualified men to lead us on to conquest and glory. Therefore it is, that we made effectual resistance: therefore it is, that we obtained our independence and humbled our foes. Without his care and support we had been overwhelmed, when men rose up against us. Without signal and almost miraculous interpositions of his providence, we had now been groaning under the tyranny of a foreign master. But instead of this, he hath made us honourable among the nations. What, but his providential care, kept us, on our liberation from British government, from falling into that anarchy7 and confusion, which are more to be dreaded, than the rod of tyranny, or a state of barbarism? Who, but the God of peace, hath united the hearts of so many millions of our citizens in the adoption of a form of government which is emphatically the envy of most other nations? Great reason, also, have we, as a people, to acknowledge and adore a superintending providence in placing at the head of the national government a succession of wise and able statesmen, under whose administration, marked with firmness and yet with moderation, we have enjoyed “great quietness.” Why is it that we have not been involved in the feuds and quarrels of Europe? Why have the sighs and groans of our citizens, who fell into captivity in a foreign land, “where ferocity growls and poverty starves,” ever been wafted across the deep and made to reach the ears of our rulers? Why is it, that the bones of our brave countrymen, who went, in obedience to the voice of our government, to effect the release of the unhappy prisoners, are not now mouldering in the “Lybian desert?” Why has such success attended the measures of our national government, that peace and prosperity have been diffused over the extended country of the United States? Let the voice of inspiration decide. “The Lord reigneth, let the earth rejoice; let the multitude of isles be glad thereof.”

But we are to remember, that the continuance of our prosperity must depend on the improvement which we make of our privileges. Means of happiness are sometimes possessed, where happiness is never enjoyed, or is of short continuance.

In the natural world, it seems to be, in some measure, necessary, that the Deity should operate in a steady, uniform manner, according to certain rules, steady, uniform manner, according to certain rules, causing the same effects constantly to follow from the same causes, that men may gain a proper knowledge of things around them, lay their plans with wisdom, and govern their conduct with discretion. Were there no settled order, no fixed connection in things and events, there would be no foundation for foresight, no ground for exertion, no reason to expect that we should obtain our desires by the use of means. We should be involved in total darkness and absurdity. God, therefore, in thus causing things to take place, in his providence, in an established order, and in conformity to certain rules, not only manifests his power, but his wisdom also, and his goodness, faithfulness, and constancy.

With great propriety may we apply this maxim to the conduct of nations. “Righteousness exalteth a nation; but sin is a reproach to any people.” This is the declaration of heaven. We can never form any just expectation, therefore, that the blessings of heaven will long be conferred on us, as a people, if we do not suitably regard the statutes of the Lord. The glory of Nineveh, Babylon, Jerusalem, Carthage, Athens, and Rome had not departed, if they had known and pursued the things which belonged to their peace!

It may be suitable then to turn our attention for a few moments to some things, which are naturally conducive to the happiness of the community.

To this end a civil constitution, which secures, and laws, which guards our rights, are undoubtedly necessary. Something more, however, is requisite in order to ensure the continuance of publick happiness. The best constitution is useless, as to the ends of government, if energy be not given to it in administration; and in vain are the most salutary laws enacted, if they be not faithfully executed and strictly adhered to as the measure of administering justice.

To a suitable provision for national defence we are also urged both by duty and interest. A people who wish for peace, must be prepared for war. For security at home and defence against foreign invaders, a republican government must depend on the natural strength of the country. One of its first objects, therefore, should be to provide for a well organized and well disciplined militia.

Industry must also be encouraged. The industrious man, while he serves himself, likewise serves the publick. The number of inhabitants alone will not ensure national felicity; they must be usefully employed. The slothful man is a curse to society. It feels the loss of what it might have gained by his industry. A mere drone in the hive, he adds nothing to the common stock. Living on the toils of others and disregarding divine precepts, he deserves to starve for his idleness. Were ever member of the Commonwealth to follow his example, all would go to ruin.

Temperance, sobriety, and frugality are subservient to the publick welfare. Extravagance, if it impoverish individuals and families, must necessarily injure the community. Intemperance and luxury debauch the mind, enfeeble the body, and degrade man to a level with the brute. They tend, of course, to the destruction of social happiness.

Suitable care relative to the instruction and education of youth is of great importance in civil society. By the history of all ages and nations we are assured that ignorance and misery accompany each other. To neglect the proper instruction of youth, therefore, is to entail publick misery on succeeding generations.

Sound morality is the stability of a government. When national virtue is gone, the foundation of publick prosperity is destroyed. As then we would hope for the favour of heaven; for a divine blessing on the means used to secure and perpetuate our publick tranquility, let the practice of humanity, kindness, benevolence, hospitality, and the like, become generally prevalent; yea, let a personal and general reformation in morals be our first, our highest concern.

With peculiar gratitude should we advert to the dispensations of divine providence towards the people of this Commonwealth. Singularly favourable have been the means of knowledge, virtue, and happiness, which they have enjoyed. Long have they been blessed with a succession of wise and virtuous rulers. The united exertions of our citizens have, from time to time, been called forth, in support of a government, which secures each individual in his person, name, liberty, and property; a government, the direct tendency of which, when duly administered, is to punish the vicious and protect the innocent. Our lands have been cultivated with success. Rich harvests have rewarded the toils of the husbandman. The hills have been covered with flocks, and the vallies with corn. The artificer hath not labored in vain; and, to use the language of another, our “commerce is an astonishing spectacle. It is coextensive with the circumference of the globe. Most of the inhabited countries of the earth are visited by our navigators, and the striped flag of the Union flutters in the remotest harbours. Cargoes have been derived from the depths of the ocean, and markets before unknown to commercial men have been found by our seamen.” Schools for the instruction of youth have been encouraged, and publick seminaries of learning have been founded. Beautiful temples are erected for the worship of Almighty God, and the rights of conscience are understood and vindicated.

Waving a consideration of the advantages, which we enjoy for improvement in arts, in sciences, in manufactures, we may thankfully notice the prevalence of health in our populous towns, in which we have been highly distinguished above some other portions of the Union. What, but the good providence of God, has saved us from the contagious disease, which has prevailed, for several years in succession, in some parts of the United States? God hath visited them with the pestilence which walketh in darkness, and with the destruction which wasteth at noon day. Death, with a sudden and awful hand, hath swept many to the grave. Multitudes, who beheld the scene, were filled with consternation. They fled from the hand of the destroying angel. We, who but heard of these things, were struck with terror. The contagion, if commissioned, might have pervaded every city, every town, every village, and brought death and destruction on its wings. Many of our citizens, might, ere this, have been numbered with the dead. But our heavenly Father hath watched over us for good.

Ours, also, is the blessing of peace. The year past has been a year of blood. The nations of Europe have waded in human gore. But how different, on this anniversary occasion, is our condition! Assembled with the heads of our tribes in this city of our solemnities, we tremble not, in view of civil dissensions; we fear no foreign invader. We behold no desolation of our coasts by war, nor the flames of burning towns. We record not the wounds and death of our friends in battle, nor the lamentations of helpless children, nor the tears of the disconsolate widow, nor the blasted hopes of parents. “Now, therefore, our God, we thank thee, and praise thy glorious name.”

Happy have we been in seeing the first office in the Commonwealth filled by one, whose reputation for talents, integrity, and patriotism is not the mushroom growth of a night. He lived and acted in times, “which tried men’s souls,” and was found faithful. But it is not the business of the speaker to eulogize. We trust, however, that His Excellency derives consolation not merely from a view of the many and important offices, which he has holden with dignity under the state and federal governments, but principally from a consciousness of having acted with upright views, and having, under God, contributed to the happiness of his country.

Reelected to the chief magistracy, may he ever discharge the duties of his important station with honour to himself and usefulness to the State. In the expectation of this we are warranted from the ability and apparent faithfulness, by which his publick services have already been distinguished. We believe that the welfare of the people will be kept in view by him, in the measures of his administration, and that he will adopt those methods, which are consistent with his rank and the duties of his station, to conciliate their affections. “To heal private animosities, and to prevent them from growing into publick divisions, is one of the principal duties of a magistrate. It too frequently happens, that the most dangerous publick factions are, at first, kindled by private misunderstandings. As publick conflagrations do not always begin in publick edifices, but are caused more frequently by some lamp, neglected in a private house; so, in the administration of states, it does not always happen that the flame of sedition arises from political differences, but from private dissensions, which, running through a long chain of connections, at length affect the whole body of the people.” Long may we be blessed with a chief magistrate, who, rightly understanding the true interests of the people, will be disposed to devote all his powers and influence in subserviency to their highest good.

His Honour the Lieutenant Governor, the Honourable the Council, Senators, and Representatives of the Commonwealth will permit us to remind them of the just claims, which we have upon their zeal and fidelity in discharging the duties of their respective stations. Raised to publick office by the suffrages of a free people, may they, in all their deliberations and decisions, be actuated by a suitable regard to publick utility. Highly important it is, that they who “rule over men should be just, ruling in the fear of God.” The oath of God upon them should lie with weight on their minds. Never should they be unmindful of a superintending Providence, nor of the final retributions, which await them as subjects of moral government. The day cometh, when “God shall bring every work into judgment, with every secret thing, whether it be good, or whether it be evil.” Acting under the influence of this solemn truth, civil rulers cannot fail of being instrumental in promoting the prosperity of their country. “When the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice; but when the wicked bear rule, the people mourn.” “It is to be expected,” says a writer of the present day, “that rulers should form the character of the people, and not that the people should form the character of rulers. It was never known that the house of Israel reformed one of their loose, irreligious kings; but it was often known that one pious, exemplary king reformed the whole nation.” Rulers, who live under an abiding sense of their obligations to God, and who suitably regard his word and institutions, will not fail to command the esteem of their fellow men.

Many things call for the attention of those, who, while acting in their legislative capacity, would keep in view the good of their constituents. One is, suitable provision for the instruction of youth.

By instituting schools, and establishing publick seminaries of learning, our fathers were, under God, peculiarly instrumental in transmitting knowledge, religion, and virtue to their posterity. To this day, we reap the benefit of their exertions. Had they been negligent of their duty, in these respects, we might long before this time, have lost our liberties and religion, and sunk into barbarous ignorance and superstition. Our university, colleges, and schools of useful learning, therefore, and all measures which may with propriety be adopted for the moral instruction of children and youth, will, we trust, readily receive the patronage of our civil rulers.

Equally mindful should they be of their obligations to promote a due observance of the Lord’s day. Aside from its subserviency to the purposes of piety, the Sabbath is of great efficacy in the preservation of civil and social order. The blessings of family subordination, of well regulated civil government, a general diffusion of knowledge, and, in short, all the blessings of life, are, in a sense, secured by a proper regard to this divine institution.

All trifling with sacred oaths should be discountenanced by legislators. By an oath, men are bound to truth and fidelity. In proportion to the contempt, which is felt towards the religion of an oath, is the insecurity as to property, reputation, and life. The want of a proper sense of the solemnity and obligation of an oath is, at this day perhaps, a growing evil. Its destructive influence relative to private and publick felicity cannot now be fully unfolded. But whatever remedy may be in the power of rulers to provided against this evil, certainly demands their attention.

No measures, we trust, will be neglected by the government of the Commonwealth, which may have a tendency to support and strengthen the union of the States. On this subject, our beloved Washington, “though dead, yet speaketh.” How forcible, how convincing his instructions! How important that we listen to his warning voice! It is for our political salvation! “Every kingdom divided against itself, is brought to desolation.” “Divide et Imperas,” is not a modern maxim of European cabinets. Powerful motives at the present day are set before us in divine providence to guard against dissension. A cloud hath risen in the east, extending along to the south; the heavens gather blackness; thunders begin to rumble! This, however, may be dangerous ground: I forbear. But, who can contemplate the late aggressions within the limits of our newly acquired territory; who can behold our commerce unjustly embarrassed; our flag insulted in our own harbours; the property of our citizens torn from them by the hands of pirates; some of our seamen instantly murdered; some detained in unwelcome service, and others carried into unhealthy climes, where they are snatched away from their friends and country by untimely death, and not feel the necessity of our united exertions in support of a common interest? To seek for publick happiness in a division of the States is madness, equal to that of a passenger on board a ship, who would set fire to the magazine, that, by destroying all on board, he might have a better opportunity to plunder.

With pleasure we behold so many ministers of the sanctuary present on this occasion. Moses and Aaron may walk together with united exertions for the publick good, if they do not infringe on the rights of each other. If the labours of the statesman, when rightly directed, tend to secure and perpetuate our civil and religious privileges, he who serves at the altar contributes to the same important ends, by putting the people “in mind to be subject to principalities and powers, to obey magistrates, and to be ready to every good work.” We may be free from the chains of earthly tyrants, and yet know not the “liberty of the sons of God.” To proclaim liberty to those, who are in bondage to sin and Satan, is the part of the gospel minister. Here, then, my fathers and brethren, a wide field opens before us. To this service, all our powers may well be devoted. As ambassadors for God to a revolted world, we may contemplate its moral state and drop a tear. See how the “world lieth in wickedness.” See how stupidity, sensuality, and worldly mindedness prevail. See ice and irreligion triumphing in the hearts and disgracing the lives of many. See multitudes traveling, apparently, in the road to destruction. Such are the painful scenes which strike our eyes, when we look abroad upon our country. Thousands regard not even the forms of religion. Look into Europe, “where blood and carnage clothe the ground in crimson, sounding with death groans.” See the grossest vice, the most shameful debauchery, the most enervating luxury, and the most unjustifiable extortion and oppression widely prevailing. In those countries, where reformation hath not yet opened the eyes of the inhabitants to the follies and enormities of popery, the thickest darkness and the most inconceivable ignorance reign. Look we, then, into Asia. There, where lived the prophets, the apostles, and primitive Christians; where lived and died the Saviour of the world; and where once stood the golden candlesticks, the churches of Jesus Christ, now live the deluded followers of the grand impostor Mohammed, and the ignorant worshippers of the sun, moon, and stars. Among them, but here and there, a solitary Christian is to be found. In Africa, the prospect still darkens. In what heathenism and delusion are the inhabitants, who are scattered over its vast regions, involved!

If such be the face of the moral world, with what zeal and fidelity should we discharge the duties appertaining to “the ministry of reconciliation!” How fervent should be our prayers and our endeavours that the gospel, in its power and purity, may be proclaimed by suitable missionaries in all the new settlements of our country; among the savages of the wilderness; and in Asia, Africa, and the Islands of the sea! As we are to beseech men “in Christ’s stead,” to “be reconciled to God,” surely no worldly consideration should ever divert our attention from the interesting employment. Christ’s “kingdom is not of this world;” and, when his ministers are solicited by the rulers of this world, or are tempted by any subordinate considerations, to neglect the proper duties of their station, he would have them reply, as in the words of Nehemiah: “I am doing great work, so that I cannot come down; why should the work cease, whilst I leave it, and come down to you?”

Fellow citizens of this numerous assembly: “To learn obedience and deference to the civil magistrate is one of the first and best principles of discipline: nor must these, by any means, be dispensed with,” would we enjoy the blessings of a free government. “Private dignity ought always to give place to publick authority.” A great part of mankind, it is to be feared, would never be satisfied with a righteous liberty. The liberty, which is sought by multitudes, is not a power of doing right, unmolested; but of being as idle, extravagant, intemperate, and injurious as they please without restraint. By the history of all nations, however, we learn, that when a people reject that liberty, which is regulated by just and righteous laws, they necessarily fall into slavery. No privileges with which a people can be indulged will secure their happiness, if they be not disposed to make a right use of them. We may be blessed with a fertile soil and a healthy climate, and our advantages for commerce may be great, and yet, by luxury, idleness and debauchery, avarice, dishonesty, and injustice, we may sink into poverty and contempt.

Melancholy indeed is the reflection, that, even in this infant empire, so many of those who are adorned with the richest gifts of nature, and who are capable of contributing so greatly to the happiness and glory of their country, should become abandoned to vice and ignominious sloth. Enchanted by the siren voice of pleasure, they sink upon the couch of indolence, or yield to beastly intemperance. Inglorious ease or detestable enormities obscure the splendor of their talents, and extinguish the sparks of divinity. Upon the graves of such, philanthropy will drop a tear, and lament, that genius, the fairest gift of heaven, should thus be rendered injurious to man.

We may enjoy the most excellent laws and religion, and still by vice be made miserable. We may have the best constituted government on earth, and yet by strife and contention, by “biting and devouring one another” be brought to ruin. Would to God, there were none among us characterized by the apostle when he saith, “They despise government; are not afraid to speak evil of dignities, and things they understand not.” In our land, political slander, if we may so term it, has risen to an alarming height. Over the whole face of our country it spreads a gloomy aspect. It is contrary to all good policy. It is contrary to the command of heaven. It destroys the peace and comfort of the citizens. Slander is, in scripture, represented as a devouring flame. That it is so, we know by its effects. “The tongue is a fire, a world of iniquity: it is an unruly evil, full of deadly poison. It setteth on fire the course of nature, and is itself set on fire of hell.”

It is truly an eventful period, in which we live. It is in many respects, an evil day. God’s judgments are abroad in the earth. “Behold,” as saith the prophet, “the Lord cometh out of his place, to punish the inhabitants of the earth for their iniquity: the earth also shall disclose her blood, and shall no more cover her slain.” Europe is the theatre of a “strange work;” and the most approved commentators on the scripture prophecies give us reason to tremble in view of the approaching “distress of nations, with perplexity.” The “sea and the waves” are now roaring, and “men’s hearts are now failing them for fear, and for looking after those things which are coming on the earth.” Thankful should we be for the privileges by which we are distinguished above the nations of the earth; and, happy for us, if we wisely improve them. Virtuous nations will ever be the peculiar care of heaven. Divine Providence, we have reason to believe, will bestow the blessing of civil liberty on every people prepared for it, and will undoubtedly take it away from all who pervert it to the worst of purposes. In this land, therefore, may that righteousness abound, which exalteth a nation, and may we ever have wisdom to commit our publick concerns to men of ability, integrity, and genuine patriotism. If a people live under a government of their own forming, and choose their own rulers, they enjoy the opportunity of having the wisest and best of their citizens to rule over them. If, therefore, the administration of their government be corrupt, the fault is chargeable on the people themselves. In all free governments, the complexion of a people may be seen in their rulers.

The blessings of civil liberty may long be enjoyed, and then lost forever; but, “if the Son shall make you free, ye shall be free indeed.” Worldly kingdoms and states have their commencement, their summit, and sink again into oblivion. But he who died on Calvary, hath, in opposition to the kingdom of darkness, established a kingdom, which shall endure when lower worlds dissolve and die. It shall not be moved. Its beauty, order, and harmony will be perpetual. To raise up and establish this kingdom of holiness and righteousness hath been the purpose of God in all the dispensations of his providence respecting the natural, moral, and political world. To this very end have all the operations of his hand been uniformly directed. On the wings of faith and heavenly contemplation, the truly pious mind soars aloft, and feasts on angels’ food, which a beneficent Creator hath strowed through all his works of providence and grace. It sees the great Supreme enthroned on high, holding the reins of universal government, rolling on the stupendous wheels of his providence, and directing every event in such a manner, as finally to issue in the highest good of his holy and eternal kingdom. They only are “called to liberty,” in the most important sense, whose names are enrolled among the subjects of this kingdom. By the most powerful motives are we all urged, to secure an interest in its unspeakable privileges. In this, our duty, our interest, and our happiness unite. Delay may be death. Time rolls on. Our days speed their flight with accelerated swiftness. Constantly are our fellow mortals going down to the dust of death. Placed here in a world of sorrows, we tarry but for a night, and then go into another state of existence. Never shall we all meet together again, till we assemble to receive, from our final Judge, everlasting retributions. Interesting to each one of us, and truly solemn is this thought! To God, then, be given the throne of the universe and the throne of our hearts, that we may be entitled to the blessings of a kingdom, which is not gained by the alarms of war nor garments rolled in blood; a kingdom which shall abide, when the angel shall lift his hand on high, and swear by him that liveth forever and ever, “that time shall be no longer,” and when all national revolutions shall be superseded by the scenes of eternity.

* * *

When the foregoing discourse was written and delivered, it was understood that Gov. Strong was re-elected. Under this impression the second paragraph in page 23, was prepared.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!