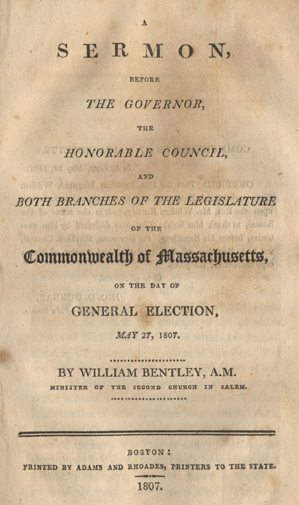

This election sermon was preached by Rev. William Bentley in Boston on May 27, 1807.

SERMON,

BEFORE

THE GOVERNOR,

THE

HONORABLE COUNCIL,

AND

BOTH BRANCHES OF THE LEGISLATURE

OF THE

Commonwealth of Massachusetts,

ON THE DAY OF

GENERAL ELECTION,

MAY 27, 1807.

BY WILLIAM BENTLEY, A. M.

MINISTER OF THE SECOND CHURCH IN SALEM.

BOSTON:

PRINTED BY ADAMS AND RHOADES, PRINTERS TO THE STATE.

1807.

In Senate, May 28, 1807.

ORDERED, That the Hon. Jonathan Maynard, William Gray, and Azariah Egleston, Esquires, be a Committee to wait upon the Rev. Mr. William Bentley, and, in the name of the Senate, to thank him for the Discourse delivered by him yesterday, before his Excellency the Governor, the Hon. Council, and both Branches of the Legislature, and request of him a copy thereof for the press.

JNO. D. DUNBAR,

Clerk of the Senate.

DEUTERONOMY, xxxiii. 3.

YEA, HE LOVED THE PEOPLE; ALL HIS SAINTS ARE IN THY HANDS, AND THEY SAT DOWN AT THY FEET; EVERY ONE SHALL RECEIVE OF THY WORDS.

We refer to the Hebrew scriptures, for political, united with religious reflections, as their government combined these two objects, which the Christian scriptures do not. The religious sentiments of all ages, and the nature of all religious establishments, as well as the example of the primitive settlers of New-England, have concurred in recommending the appropriate devotions of this day. But this authority extends only to received forms of devotion, which are adapted most freely to express the public consent, or may concur to assist it. The less it is a maxim of state to direct ecclesiastical affairs, and the less the state interferes with the private judgment of the man, who exercises such functions, the more surely will an ingenuous man be cautious, that the liberty he enjoys, should be sacred to the prosperity of the state, which protects him. The privileges he possesses, belong not to his opinions, but to his patriotism; not to him as a man, but as a citizen. His freedom of speech belongs to the interest he has in the public happiness, in the laws, and the constituted authorities, and in the power to excite good affections, and to promote generous purposes among the people. The state has a right to avail itself of all opinions, rich in patriotism, as it has of all other contributions for the public welfare, but it is patriotism which gives the highest recommendation. Hence we are deeply impressed with the language, which has become venerable in the character of men, who have been useful in past generations. We dwell with delight upon the ardent love of our country, displayed in the affections of a Winthrop, the prudence of a Leverett, and the patriarchal manners of a Bradstreet. We behold them concurring with the infant strength of our nation. We learn not only the opinions, but the purposes of the age in which they lived. Their success gives them glory. If we change their measures, we retain their principles. We discover their safety, and secure our own.

With these convictions, the children of the Hebrew Patriarchs, in all generations, read the lessons given to their fathers, and in modern ages, we enjoy with rapture, the legacy which, our best patriots, upon a review of their services, and of the public hopes, as the best pledge of their affections, have generously bequeathed to us.

Of this nature is the address of Moses in the text. He reviewed his whole administration at its close. In the name of his God, he declares that its sure guide, was the love of the people. The same spirit which suggested the admonitions of the Patriarchs, and gave the words of wisdom in the past generations, was invariably regarded in all the changes of their political existence. Each had a blessing; all had counsel; all received the same law. Such is the truth which is accepted from the words of the Lawgiver of the Hebrews.

Useful criticism might be employed on the words, as it would develop some antient customs; as it would explain the hopes of private virtue, and as it would suggest that Moses expected to secure his hopes of the political prosperity of Israel, not by the wisest theory, he could propose, but by the consent of the national character to the Institute he had recommended. And upon this account he gave no rules whatever for the political changes, which future ages might introduce. In the words, is an allusion to the patriarchal blessing on the saints, or heads of the families, as may be concluded, from the consent of the Hebrews, in this sense, and from the appropriate use of the term, as applied to the primitive Christians in their scriptures. The oldest version regards the distribution of the last clauses, referring the former to the instructions of the Patriarch recorded by Moses, and the latter of them, to the Lawgiver himself. Each family had its peculiar instructions, but the whole congregation received the law commanded by Moses. While the text discovers that the happiness of the people was the object of the Law, it also assures us, that the private instructions of the families and tribes had contributed to a consent in the national hopes, and upon this consent their highest prosperity did depend. And this sentiment the present discourse is designed to support.

Our enquiry then is, into those circumstances of national character, which concur to support the present Constitution of our Government. That it be well defined, well guarded, and well supported, these things are to be considered when we pronounce of the public liberty. It had been defined and enjoyed in what was called the British Constitution; It had been reformed by the boldest experiments in that nation, and had profited in an age of experiments, by all the information which could meet the wishes of a free people. The history of our settlements will explain in what circumstances, it was adopted, and the American Revolution with what spirit it was maintained. Our Constitutions are the deliberate result of our political wisdom, and our vindication before the world.

The history of our Commonwealth divides itself into three distinct and well known periods. During the old till the new Charter; from the new Charter to the American Revolution. If ever a people were born free, such were the people of this plantation. If they at first submitted to an ecclesiastical dominion, it was a submission to character, not to law, as the event proved in the third generation. Their first measure was to consult their own wishes, and to accommodate themselves to their own condition, whatever might have been dictated by European policy. Even their servants found that their freedom was an easy claim, and a sure privilege. The settlers in the name of freemen, soon took the entire direction of their domestic affairs, and their arrangements were so often varied, that they could leave no prejudices in their favour, when contrary either to their present interest or convenience. The men, who led the settlements, had possessed a superiority of talents, as well as influence, gave an early example of their own independence. They assumed their religious functions, directed by the freedom, they had long sought, and now fully enjoyed. They adopted no confession of faith, which had the authority of any Church, nor did they admit, or name any canons of any Communion. They reserved to themselves no privileges, which could support a separate interest, or an exclusive power. They associated with their brethren in the first honours. They supported no other claims, than their personal reputation, and the public confidence could give them, while they entrusted all the power, which could be given by the association of brethren, to which they respectfully belonged, to any of their society, who were not elected as civil magistrates. And to exercise this power, nothing more was required, than a sincere disposition to find out, and encourage the best wishes of each association. Their civil privileges were greater still. While no civil distinctions did exist, all the ministers by their ecclesiastical maxims were excluded from any claims to represent the freemen, refusing all weight of character in influencing the public elections in their own favour, after a representation of the freemen had been judged convenient. These privileges were carefully maintained throughout the first period of the history. The greatest events arose from the influence, which the character of the ministers had upon the first generation. Such were the affairs of Mr. Williams of Salem, who was friendly to the public liberty. Such the discussions of Mr. Cotton at Boston, and of Mr. Parker at Newbury. But we seek the cause of this influence, not in the power granted to the ministers, but in their character, which gave authority to their opinions. The Synod which was called to give consistency to these opinions, by the manner in which its authority was admitted, has explained the public will; and in a succession of curious facts, has shewn how the superiority of this order of men had locally obtained.

The primitive ministers of New-England will justify an honourable comparison with any who have appeared in succeeding generations, and can maintain an evident superiority to all who profess to follow them in the same dogmas, and in the same course of studies. They were better acquainted with the learned languages, better informed in ecclesiastical history, and more deeply versed in scholastic and polemic divinity. They corresponded with the best men of their times, and had their works printed in Europe under the inspection of the best scholars, and at the best presses, and were acquainted with the private opinions of the leading men in the several communions of the Reformed Church. And many of the best men, who remained in Europe did not conceive it unworthy of their reputation, to entertain hopes of being united with them in the same settlements, for the promotion of Christian knowledge.

A comparison so favourable to them, when made with the generations which succeeded them, might be thought to be peculiarly happy among their own associates. But we should remember, that the display of their zeal and of their talents, was the favourite object of the settlements, while the condition of the society, in which they lived, operated against all the other members, as much as it did in favour of themselves, in regard to all the advantages to be derived from European improvements.

We are not left to uncertain tests of that knowledge which prevailed among their companions. Many might be drawn by interest and by local prejudices to embark for a new settlement, and for new hopes of prosperity. But men engaged by religious systems, and possessed of talents to distinguish their friends, do not hazard all their purposes with such men only. The persuasion was, that the company had common views, and as men of enterprise all the first to search into the truths of religion, as well as to make new experiments in nature, and the age of the arts, is an age of enquiry, that the company had embraced men of sound understandings. In all the rising sects of the Reformation, men of sound minds were found to give a sure direction to the sober minds of their brethren. The period is not so distant as to render it impossible to obtain the proper evidence of these facts. We can reach the occupations, the condition, and improvements of the first settlers, and though the greater part were in common employments, yet they were not without some of the best instructed men of the age. The best books, then known, were found in their possession, and Grotius their contemporary, has been compared to Tacitus himself. They displayed their knowledge as soon as they had occasion for it. They possessed in ship building the knowledge which the French had communicated, and which a late English artist has rendered familiar to his countrymen. They held all the valuable books on the subject. The first publication at Oxford of a contemporary of Vinci, whom Hogarth and the notes of Fresnoy have noticed, was with the first settlers.

The Military tracts which had the fame of the day were in their hands, and the private collections of books were made with good judgment. But they soon found that their condition offered no encouragement to the arts they possessed, and the knowledge of the first generation was succeeded with an education accommodated to their circumstances, and of consequence the arts and sciences were not in the second generation what they had been in the first. The works of the first ministers of Salem, Boston, Ipswich, Newbury, Cambridge, and Roxbury, and of other antient settlements, exist for a fair comparison. They who examine Mr. Ward’s publication and recollect that it contained the true doctrine of the first ministers respecting religious toleration, and compare it with many facts will ascertain that they differed not essentially from the opinions prevalent in Europe. The Synod then did not possess the power they were inclined to exercise, and the condition of the settlement obliged the ministers to correct a zeal which would have been daily encroaching upon the civil constitution. The jealousy which the British nation had of the settlements in America, and the intention to exalt its own power, obliged the ministers to do nothing without the consent of the people. And the persecution, at last obtained a full commission, it had its authority only in the superiority of the ministers and in the general consent of Europe. This superiority would eventually have been fatal, had not persecution been cruel, and enthusiasm extreme. And had not the condition of the settlements, entirely changed the relative importance of character among the people.

The Literary establishments, which from the wisest policy obtained at an early age, had not that strength from great talents, which give them a sovereignty in their influence. Knowledge, not so great with a few, was more equally distributed. The residence of Masters in the Arts in any infant country could not produce such an effect as arose from the habits of Europe, and could not be maintained with benefit to literary institutions without rich endowments. They belonged not to a large school into which the higher instructions could hardly be permitted to enter. And hence in the second generation, the ministers found their influence lessened by every attempt to maintain it, without a visible superiority of talents and character, and themselves reduced to such a share of favour, as they could procure by their usefulness, and their sincere affection to the people.

The character of society had insensibly changed. It was no longer an association in favour of liberty against heresy in religion, but of liberty against all its enemies. And thus every occurrence contributed to check, in the safest manner, any abuses, which could arise out of the public prejudices, and the old charter expired, and the new found us free.

The precedency of the civil to the religious character, might occasion new dangers. But the second period of our history proved as safe as the first. The state of affairs in the English nation, during the first period, had tended to confirm the inhabitants of these settlements in their early love of liberty, by better writings, and more powerful examples than they had before possessed in the times of the Republic. The restoration, while it promised nothing to the ministers, engaged them to prevent the attempts to extend the royal prerogative in America. The Revolution which promised moderation in Europe, promised nothing to the English settlements in America, but a system of dependence. Other settlements in the neighbourhood of our own, in which royal claims were acknowledged, led us to expect a common fate, when the last minister of religion employed in a civil negotiation, returned with a new Charter, an event expressive of the influence of his own order, and of the new dangers of his country.

Here commences a new period.

All the ecclesiastical institutions discover it. The toleration which appeared in the capital, and the changes in the forms of worship admitted in the Congregational churches at the opening of the eighteen century, discovered that a new order of things had begun. The contest now was between the two countries. The means of education had been most profitable, as they always will be, to men, whose talents are demanded by great occasions, and whose associations are strongest with ambition. The chief magistrate, to the antient habits of the people, was a stranger. He was not of their election. The contest then was between the officers of the Crown, and such men as ambition could awaken to defend the people. We look then among men instructed in public business for the great characters of this age. The ministers had not only generously declined civil offices but they had repeatedly consented to give up to the public wishes the instructions of their first institution for public education. The concession was in consent with the national character. The best talents were required in public affairs, but with a sure check from the British administration. Every domestic obligation united to keep in the interest of the people such as had not employments from the British Crown. The history of the Cookes, and of the Governor’s negative may explain the competition of talents and of power. The father and the son maintained the public favour for sixty years, but not without that jealousy which is awakened by the love of liberty. The vigour of the public character was not disgraced by the ambition which preserved any portion of North America from the dominion of any foreign power. The expeditions which distinguish these periods, and the second in which these settlements discovered their military spirit, as well as the last which extended the English dominions, are from the same principles which directed the negotiation, and which have united eventually, in our own times, the discoveries of Raleigh and Drake in the same empire. The times which preceded the American Revolution are well known. The British Constitution embraced the Church and the State, and the jurisdiction of the one might accompany the other. If the ministers had departed from the opinions of the first settlers, and had become more favourable to religious liberty, they had not lost the affections of the people, or the love of their own independence. Their union neither oppressed their understandings, nor lessened their interest. Alarmed at the dangers which threatened them, they made a bold and seasonable defence. The controversy which is in our hands, has rendered dear to us the names of the men who engaged in it. This zeal which consented to the spirit of the times, has given us a list of ministers, whose memory must exist in our history, and whose praises will be recited, as long as our national existence can continue.

We now behold a space great as the first, in which religion had all its honours, the mind all its freedom, while a generous defence of the public Liberty was maintained by the best talents of every class of citizens, and by the best literature of our country, and the cause had all the glory, which national favour could bestow. Such were the springs upon the public mind, when the nation resolved to declare its Independence, to vindicate its rights, and maintain, by the sword, its political existence.

At the commencement of the third period of our history, the most powerful domestic causes combined to assist the public liberty. They were felt in the energy of national character, in the system of education, in the freedom of elections, in the confirmed patriotism of men who filled the first offices of state, and in a good Constitution of Government. We have seen the strength of religious character guarded against the prevailing abuses, by causes which concurred to render the teachers of religion the sure friends of the people. The spirit of the laws, the character of education, and a political necessity contributed to this important end. In the next period, we see all the ambition of patriots corrected and refined by the struggles of men appointed to assert every claim of foreign dominion. The people were taught to reverence their benefactors without concessions unfriendly to their liberty, and to listen to patriots, whose claims on the public notice were, from the guards, they placed against every encroachment on the public liberty.

The energy of the national character was seen, in the full consent to measures, which involved every interest, obliged the greatest personal services, and never presented any rich hopes but in their eventual success. When opinion was irresistible to every plea of wealth and ambition; when habit in domestic, or social, or professional life had no prejudices firm enough to oppose, and when all could perform, more than they promised or expected, this was national strength and glory. And who that contemplates the danger, the struggle, or the event, can deny it to us in the most favourable circumstances of a great revolution.

Every thing contributed to put education under restraints most favourable to the national character. The schools had not been so associated with the State, as to receive any influence, unless by private manners. The laws had left them altogether to the rules of the respective incorporations. The teachers were approved by those who were to be instructed by them. They had not under any pretence departed from this simple character, and it was rendered necessary that our highest institution of public education should have a government directed by the legislative wisdom which ruled the State. And it is a pleasing recollection that at this time, the man who had the greatest influence in the State, was possessed of the highest reputation in the University, and of the most powerful direction of its studies. A circumstance the more memorable, as he was lineally descended from the first Governor Winthrop, 1 and united in himself a portion of all the powers exercised by the consent of the people. In possession of a seat in the Council, and of unrivalled eminence in his professional abilities, he was able to provide confidence in the people, and literary pursuits could remain uninterrupted by any jealousies that they embraced objects not favourable to the public liberty. And thus our University escaped from all the evils of the war.

Our religious institutions were in the same happy consent with the national character. The jealousies of foreign establishments had corrected the strong propensities to an imitation of new forms, so that nothing spoke to the senses in favour of the prejudices of foreign nations. Whatever was thought, could not be silently expressed. And the manner was our own. The teachers of religion held on accountableness to their respective incorporations, and they could not combine against the laws. Their associations were useful to them, only as they rendered the members more worthy of the public affections. No uniformity of ceremonies or opinions had imposed a form of doctrine or discipline. The results of Synods and Councils were consulted rather as precedents than authorities. The State was favourable to this religious education, because it regarded all the means, which a pure conscience may enjoy, a sober life recommend, and a quiet citizen freely accept.

The electors of the State were, at this time, of the highest value, and in their greatest honour. They had dangers, rather than riches to bestow. They required great labours, which they could repay only in gratitude. The reward was in the prosperity of the state, not of the person who performed the richest services. The promise was of fame, but neglect of duty was infamy. At once a host of heroes arose. Great occasions produce great men. We had men wise in counsel, powerful in arms, the deliverers of our country. They who commenced patriots in the revolution, continued their services till peace was restored, so that we found ourselves with the same friends, who engaged with us in the first dangers.

From these advantages resulted our free Constitution. Dr. Franklin said of one of our Constitutions, “I consent to it, because I expect no better, and because I am not sure, that it is not the best!” It is in just consent, with the great civil privileges on which the plantation begun; it profits from the experience of modern times, and is free from the antient prejudices, which constitute parts of the European republics, and is the firm basis of our liberty. It has maintained itself in the public affections, its powers have been exercised with success, and it still lives in the health of the nation. By its own energies, it has restored itself, when it felt the approaches of disease, and it preserves the hopes of a durable existence. The world has long been accustomed to appreciate its own moral advantages. A refined skill has done wonders upon an infirm and vitiated constitution. But severe rules seldom resist long habits. Health is easily nursed, when life is pure, by temperance, by energy, and a free spirit. A sound constitution promises every blessing, and sacred should be the charge to preserve it.

How painful would be the recollection, that they who were the most active to form our constitution of government, were the first to renounce it. That they should not dread the dangers of military power; should not fear oppressive excises; should oppose no established orders in the State, and should consent to change the form of the government. That men who instigated the public resentment against all oppression, should ridicule the patriotism they had excited. Roused by injuries, nations have been called to assert their liberties, but we are invited to our duty in the most favourable circumstances. Whatever can be attributed to habit, to association, to first choice, and best condition for it, obliges it. The love of the public liberty is maintained in the spirit of the General Government of the United States, and while we carry back to the heart, the pure blood of our veins, it is from the powerful action of the heart, life circulates freely throughout the nation. Gratitude bids us to remember our national benefactors. Washington employed our arms with glory, and Jefferson has instructed us in the arts of peace.

It is for the different branches of our Legislature to prove that they deserve to be entrusted with the administration of our affairs in these happy times. They should appreciate their talents in the dignity of their debates, in the wisdom of their resolutions, and in the impartiality of their Laws. Honesty is not less required in public, than in private concerns in a free republic. The branches of the Legislature which arise out of the fears of past ages, and are provided as checks upon the simple theory of government, should counsel with the prudence of age, and consent with the conciliating wisdom of fathers, who delight in increasing happiness. Their care should not enslave liberty, but inspire it. And while our present Governor, retires with a good conscience, and the best wishes of his fellow citizens, we may be confident that a man who has felt our dangers, and shared in the cares of our revolution; who is well informed in our history, and acquainted with our manners and laws; who has held the most important offices in the State, will support the best character of that people, which has bestowed upon him the highest honours. His virtues are to justify their confidence, and his great services to vindicate their choice, and then his fame will be immortal in his own wise administration.

Our experience might lead us to institute a plan of national education, connected with all the public instruction, from the known influence of education upon the purposes of moral and civil society. But till such designs are approved and accomplished, the condition of all public institutions should be carefully examined, and their purposes known, so that adequate means may be provided, all deficiencies supplied, and all abuses corrected. The friends of our University and other seminaries will secure the public favour by a full consent in the design of their establishments. In the city of the Republic from which our first settlers emigrated to America, the University therein established, the first in age and talents, was the first in patriotism, and free enquiry, and could boast of the most able friends of the public liberty. With the same reputation our University would enjoy its best subordination, its most ample resources, and the best praise in a full concurrence with the great ends it proposes, in our greatest prosperity.

Our experience may assure us also, of the best advantages from the instructions of the ministers of religion. Had Mr. Williams, who was the first to conceive what was great, in the State, though deceived in the character of private associations, extended his doctrine of exclusive associations of religion, to civil society, he must have dissolved all its ties. He gave full liberty to every freeman, but religious association not to character only, but to opinions. He conceived them inseparable. He attempted to follow the order of common life. This admits a sacred choice in the family, and an innocent freedom in the world. But all errors of judgment or life cannot dissolve the family. So far he must deserve our commendation, as he did not make the religious association interfere with civil liberty, and was bold enough to declare it.

The arts and genius may attach themselves to an obstinate superstition. We are not necessarily well informed in everything. The population may require indulgence to endless prejudices, born in the varied education of man, and the existence of all civil liberty may depend upon freedom from all prosecution in religion. The state must not then fix bounds to enquiry into religion, more than to any other researches of genius. The strength of the religious character should be most strongly united to the best character of the citizen, and he should be considered as the best minister who is most happy in preserving and uniting them. The Priesthood of Moses, very limited in its offices, was so disposed that we have no history of its opposition to the Laws. The establishments of the East are upon the same principles. If the laws are of a mild character, they are in more full consent with the benevolent religion, which is the just name of the Christian faith.

May we find those happy times in which our national character will confirm all our best hopes for liberty and peace. May no event disturb the kind succession of prosperous days in our history, and may tradition speak in all ages, of the same character, which has been to us a fair inheritance. A rest, O Lord, to the many thousands of Israel,

Thou loving Father of the people.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!