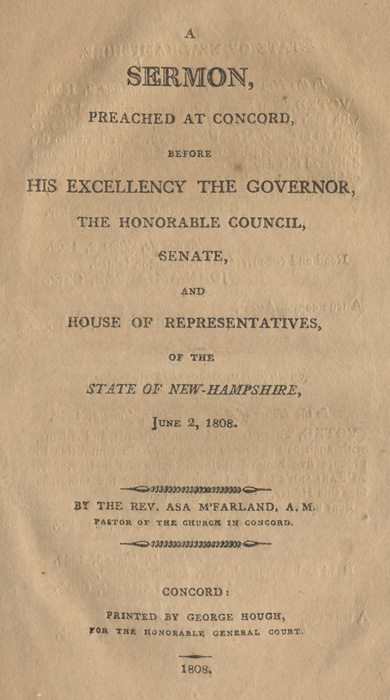

Rev. Asa McFarland (1769-1827) preached this election sermon in New Hampshire on June 2, 1808.

SERMON,

PREACHED AT CONCORD,

BEFORE

HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR,

THE HONORABLE COUNCIL,

SENATE,

AND

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES,

OF THE

STATE OF NEW-HAMPSHIRE,

June 2, 1808.

BY THE REV. ASA M’FARLAND, A. M.

PASTOR OF THE CHURCH IN CONCORD.

II PETER, I. 19.

But we have also a more sure word of prophecy, where unto ye do well that ye take heed, as unto a light that shineth in a dark place.

MANKIND have, in all ages, been disposed to associate religion with the most important transactions and events of life. The Grecian states committed the guardianship of the great oracle at Delphos, to the general council of the whole nation, that they might the more certainly secure the favor of the deity, who was supposed, through the medium of that oracle, to communicate his will. Lycurgus, who instituted laws for the government of the Lacedemonians, consulted the same oracle, that he might commend the laws which he made, to the regard of his countrymen, by suggesting that they had the approbation of the divinity. For a similar reason, Numa Pompilius pretended to have had intercourse with the goddess Egeria, who dictated those laws to him by which Rome was to become the mistress of the world.

These men, though not favored with the advantages which we derive from divine revelation, were well versed in the feelings which govern mankind. The reasons which influenced them to consult the oracle, and publish laws under t pretence that they were communicated from heaven, have their foundation in one of the most powerful and operative principles of human nature, a principle of religion. The necessities to which men are subjected in this life, impel them to seek aid from above. Their hopes and their fears lead them to adopt some form of religious worship. Whether the object of their worship be the sun and moon, the stars and the elements, or the great Jehovah himself, who formed the light, and who createth darkness, they must seek relief from their distresses, dispel their fears, and cherish their hopes, by some supposed, if not real, intercourse with the Deity.

As mankind must have some religion, it becomes of course necessary to inspire them with confidence in the laws, and engage their conscience on the side of obedience, that they should believe them to have the sanction of divine authority. This principle is so interwoven with all their feelings, and it is so readily excited on every new occasion of alarm, that no change of manners, nor different mode of education, nor the lapse of ages, can prevent its operation. If improvements are made in philosophy, or in the science of civil government, they can modify, but not extirpate, this principle. In this respect man is ever the same. He cannot find means to quiet his mind in the moment of alarm, nor any prospect to keep his hopes alive, unless he have recourse to some principles of religion.

While legislators of antiquity consulted a pagan oracle to know what institutions they should adopt, or rather to give them efficacy when adopted, we, my hearers, have a more sure word of prophecy. In the Christian dispensation we have more infallible indications of the divine will, and more certain principles to guide us, as well in those transactions which are of public moment, as in the private walks of life. As men must have some religion to regulate their conduct, attach them to society, and enforce upon their conscience respect and obedience to civil institutions, wise men will choose and cherish that which most effectually answers these purposes. They will encourage that system which most effectually controls those passions which tend to the subversion of government, that which fixes on the mind of men the deepest and the most durable impressions of their accountability to God for their conduct in society, and binds them one to another by a common interest.—We have a religion in the Holy Scriptures which answers these purposes.

Hence I shall endeavor to illustrate this general truth: The Christian dispensation, more than any other system of religion, is favorable to the true end of civil government.

Those whose professional employments have led them to contemplate government in all its branches, are better qualified than I am to explain its nature and end; and it does not become me to discuss subjects of this nature; but as I have proposed to prove, that the influence of the Gospel is favorable to the end of civil government, let it suffice on this occasion to say, that the true end of government is the common safety; and to secure this end, there are dispositions in mankind which need to be corrected, and passions which need to be controlled; and they must be controlled y restraints of powerful efficacy, or the safety of a community must inevitably be endangered.

I am now to prove, that the Christian dispensation has the happiest influence to secure this end.

1. Because its restraints reach the temper of the heart, where only they can rectify or wholly prevent the evil. It is in the hearts of men that all the mischief is conceived, arranged, and matured, which interrupts the public peace, and converts the world, at times, into a melancholy scene of oppression and violence.

The heart of the ambitious usurper is that secret asylum where he first conceives the design to overturn lawful authority, and exalt himself upon its ruins. Here it is matured, and his future operations are marked out. Here the oppressor fixes upon the man whom he intends to ruin; and arranges the plan by which the fraud is to be managed. In this asylum, which is fertile in every species of iniquity, the adulterer designates the family which he intends to involve in disgrace and wretchedness, singles out the unfortunate object of his criminal passions, and securely exults in the prospect of success.

Murder also begins here. It has its origin in that malice, or lust for plunder, which being indulged in the heart, become too riotous for restraint. Into this asylum of iniquity no human eye can penetrate. NO human remedies can reach the disorders which rankle here, so as to heal them. Whatever mischief is conceived in the heart, human laws cannot rectify, until it is manifested in overt acts. The officer of justice cannot enter and seize the lurking enemy, before he has begun the work of destruction.

It is however desirable and necessary for personal and public safety, that some effectual restraint should be laid on the intensions of men: for when the criminal design is brought to maturity, and the man has already begun to commit deeds of violence, the evil, at best, can be rectified but in part. The religion of the Bible furnishes this desirable restraint. The word of the Lord is quick and powerful, sharper than any two edged sword, and is a discerner of the thoughts and intentions of the heart. It arrests the guilty purpose before it is ripened for execution. Here men are taught, that though they may avoid disgrace, and escape punishment in this life, on account of criminal intentions, yet there is another tribunal. They must appear in the judgment before God, who now looketh at the heart, and requireth purity in the inward part, and who will bring every work into judgment, with every secret thing, whether it be good or evil. At that awful tribunal, the intention to commit a crime will be found criminal, even though the crime had not been perpetrated.

Where the Scriptures have their effect on the mind, they already create some anticipations of the judgment in those self-reproaches which men experience when they harbor iniquity in their hearts. This religion begins its salutary work at the foundation. It rectifies the motives and the intentions of the heart; and when the heart is restored to order, it is easy to regulate the conduct of men. With the powerful aid of such principles deeply impressed on the mind, civil government can, with great ease, accomplish its object—the safety and happiness of a community.

As all these principles are denied, so these salutary restraints are removed, at one stroke, by infidelity. The man who believes and who acts on the principle that he shall not be called to account, in the future world, for his temper and designs and conduct in this, may allow himself great latitude. He can, and probably will, do much mischief in ways where it would be impossible for human laws to detect and punish him. He can deceive; he can oppress and defraud, and perhaps destroy the comfort of families, by his impurities; and if men of this description have conducted with decency and sobriety, it must be imputed to the remaining influences of a Christian education.

If we would contemplate the full effect of infidelity, we must conceive at least a new generation, on whose mind there is no trace of religious truth, and no principles of conduct which have their origin in revealed religion. Among such a people, it would be difficult indeed to secure the public safety. Fines, imprisonments, and corporal punishment, would be feeble restraints; too feeble to control the violence of cupidity: and as to maintaining a reputation, and avoiding public disgrace, they would not be under a necessity of restraining their passions for this purpose; because, in such a state of things as that which I have supposed, it would not be disreputable to commit any enormity which men choose to sanction by custom.

The religions of the pagan world, in their moral tendency, were but little preferable to infidelity. It seems their principles never reached the heart, at least not so as to correct its vicious propensity. In every form of pagan religion, there were encouragements held out to men to practice those immoralities which must inevitably interrupt the public peace. If the principles of their religion reached the heart, they could not produce any useful effect; for it could not be supposed that the morals of men would be pure, when they worshipped deities who were supposed to indulge in all the excesses of wrath, revenge, lust, or intemperance. Men, who have had the best means of knowing the moral state of the pagan world, have testified that St. Paul exhibited a true representation in the first chapter of Romans, when he said they were “filled with all manner of unrighteousness, without understanding, covenant breakers, without natural affection, implacable, unmerciful.”

The religion of Mahomet, it is well known, does not better secure the morals of the people: for that portion, which is not evidently taken from the Gospel, encourages them in the most abominable licentiousness. It is enough to say, they are taught to expect sensual enjoyments in Paradise, to reward them for spreading slaughter and destruction over the earth.

2. The Christian dispensation is favorable to the true design of civil government, not only because it lays effectual restraints upon the criminal intentions of men, but likewise because it distinctly specifies the whole system of their public and social duty in detail.

That mankind may be trained up in those habits which will make them good subjects in a community, it is necessary, not only that they be governed by pure motives, but they should also be well informed in the nature of their obligations. It is impossible but that a man should fail in many instances, however honest his intentions may be, if he be ignorant of his duties. The Gospel is commended to the regard of every wise man, on account of the universality of its principles; for they embrace every possible relation, and they are applicable to every case. If a man, with an honest and good heart, take his direction from the Scriptures, he will find how he ought to conduct in every relation, to his Maker, to civil rulers, to his family, and neighbors, and to mankind at large. In every case of doubt, he may find here some salutary direction. If he commit his ways to the Lord, his thoughts will be established. If he have committed mistakes, here he may learn how to rectify them: and if his hopes be disappointed, and his prospects cut off, he will find those consolations which will save him from total despondence.

The Gospel has made the best provision for the education and the government of youth, by guarding the marriage covenant with the most awful penalties. Are you placed at the head of a family, you are taught that God has put a governing authority into your hands, and made the future character and condition of your children to depend, in some respect, on your faithfulness. He also teaches you, that you are responsible to him for the examples which you exhibit before your household, and for the habits which your children form under your instructions. Are you a subordinate member of a family, your obligations to honor and obey your superiors is made exceedingly plain; and your correspondent duties are enforced by the promise of long life and prosperity here, with the favor of God beyond the grave, and the fear of incurring his everlasting displeasure.

That this provision, which the Gospel makes, for the early education and government of youth, has a happy influence to aid civil government, will obviously appear when we consider, that it is in the family circle where the youth receive those impressions which will remain and characterize them through life. Here they imbibe their most permanent principles of action. If care be used in their early instruction and government, there is a probability of their being peaceable members of the community; but if they are not habituated to subordination in their minority, they will not patiently endure it when they shall act for themselves. The strong arm of civil government must be exerted to control habits which have been fixed by age, and deepened by repetitions of sinful indulgence; and notwithstanding what the civil authority can do, the public safety will be endangered by such unsubdued spirits.

If infidelity does not go to the utter dissolution of the marriage covenant, it certainly removes from the mind a sense of its sacred nature, and therefore in effect it destroys those relations which alone can insure the proper care and management of youth. When men no longer believe that they are accountable to a divine tribunal for their conduct in their families, whatever care they may use to furnish their children with exterior accomplishments, or leave estates to them, it cannot be expected that they will be in any degree solicitous in forming their moral character. Such men will generally be either insupportable tyrants in their families, and vent their spleen upon those whom they should govern with a steady hand; or, neglecting all rule, they will suffer their children to form their own habits, and govern themselves.

Nor are the various forms of Pagan and the Mahometan religions much better in this respect than infidelity. They do not guard those domestic relations of husbands and wives, parents and children, from which only the public may hope that the morals of youth will be secured. When we find that polygamy, and an almost unlimited concubinage, were not incompatible with the principles of their religion; and when such abominable practices are encouraged by the example of persons in the highest stations; we may easily conceive, that as St. Paul says, they are without natural affection, covenant-breakers, and given over to a reprobate mind, to do those things which are not convenient. All those bonds which attach husbands and wives, parents and children, are loosened, if not wholly dissolved, with them; and, therefore, their religion furnishes no principle that may be relied on for the proper government of youth.

3. The influence of the Gospel affords the best aid to the civil government, because its principles are unchangeable. They are the same to men of all conditions, and to every age of the world.

Most of the prevailing religions, except the Christian, have been variable. They have been adapted to the policy of particular nations, and to the exigencies of times. The pagan nations, as either their fancy or their fears might dictate, joined new deities to their catalogue. This necessarily laid a foundation for new principles, and the institution of new rights. They had no system which embraced men of all conditions, and which was suited to every form of government. They had mysteries interwoven in their system, in which the learned pretended to receive degrees of light and knowledge in divine things, which were not to be exposed to the great mass of mankind. But the probability is, that their mysteries were only a pretext to evade those moral obligations which were enjoined upon the vulgar, and indulge the criminal propensities of the heart.

It must be obvious, that government is most secure and permanent when the members of the community embrace a religion which is always the same; for at every new turn which the religious system experiences, the form of the government would be exposed to change. If the religion did not bind all men by the same obligations, there would be danger that one portion of the community would exempt themselves from burden, and indulge in liberties which would be hurtful to the state.

The Christian dispensation embraces men of all ranks and conditions. It does not bend to times and circumstances, or to the purposes of men. Amid the fluctuation of sentiments, the changes in men, views of morality, this is an invariable standard to recall them from their wanderings in a corrupt age. Here are no mysteries that are not to be exposed to the vulgar, where the learned or powerful may shelter themselves, and evade those moral obligations which are binding upon the common people. It is not one thing to the rich and honorable, and another to persons of humble rank. One man is not justified by the Gospel in laying burdens upon others, without bearing his own part. No change in a man’s outward condition can make void his obligations to God and his fellow creatures. It is, in short, the religion of all conditions and times, and forms of civil government.

If it be a principle of human nature, that man must have some religion, the government will unquestionably be most secure and efficient when the members of the community feel the influence of a system which binds every man, of whatever condition, to duties which he owes to God and to his fellow creatures.

4. As the Gospel is the same to the rich and the poor, the powerful and the weak, it affords at once the best security to rulers and to subjects.

Government will receive great support from a religion which adds weight to the authority of the magistrate, and which at the same time guards that authority so that it shall not be abused. Such is the light in which the Gospel places civil rulers, that their authority has a commanding influence over the minds of good men, an influence which infidelity denies, and infidels cannot feel.

In view of infidelity, the magistrate is but a creature of men, clothed with no other than human power. The authority by which he acts, is no more than that which men have delegated to him, if he be an elected ruler; or if an usurper, it is no more than a power which he has assumed. With such views, it is not possible that men should feel any great respect for the office of him who bears rule; or that they should consider it to be very criminal to oppose even the necessary exercise of authority.

In the light of divine revelation, the case is different. Here civil rulers are represented as deriving their power from a higher source than the suffrage of the community. They have a power which is calculated to command respect, and overawe the disobedient. According to the Gospel, the magistrate is not a creature of men; for though he came into office by the election of men, yet when executing the proper power of his office, he is a minister of God. He is appointed to execute the divine will, to correct and reclaim offenders, and encourage and protect them that do well. Viewing him as a minister of the Most High, conscientious men have other reasons to respect his office and obey the laws, than the fear of those corporal pains and penalties which the laws inflict on offenders. If they oppose the civil power, they have reason to fear, that they must answer to their Almighty Judge for having trampled his authority under foot.

These are the powerful enforcements to obedience, which the Gospel furnishes. “Wilt thou then not be afraid of the power? For he beareth not the sword in vain; for he is a minister of God, an avenger to execute wrath upon him that doeth evil. Wherefore ye must needs be subject, not only for wrath, but for conscience sake.”

Although Christianity throws its weight into the scale of civil authority, and engages the conscience of virtuous men on the side of obedience, it effectually guards this authority that it be not abused. It recognizes the rights of the subject, and affords the best means of his security; for though it represents the magistrate as a minister of God, it reminds him that he is clothed with this high authority for good.—Such power is not committed to him of God to be an instrument of oppression, or to be subservient to pride, or selfishness, or a worldly mind; but that he may be extensively beneficial to his fellow creatures. The very consideration that he receives his authority from heaven, lays an awful responsibility upon him; and if good men are afraid of resisting power which is derived from so high a source, the Christian ruler will be no less afraid of abusing such power.

Thus those who are appointed to rule, are endued with a power, in some respect, divine, to carry into effect God’s designs of justice and benevolence towards men, to restrain offenders, and protect the upright and inoffensive; but not to subserve a private interest. The Gospel directs the magistrate to that dread tribunal, where he must stand upon a level with the most obscure subject, to give an account of his stewardship; and assures him, that as he acts in a higher station than others, and has it in his power to perform greater service to his Maker, so more will be required of him. Having authority to bear down iniquity, and encourage virtue, to protect the innocent, and punish the guilty; if, disregarding the rights of the subjects, he has aimed to enrich or aggrandize himself, he abuses not only a power which men have committed to him, but that which he has received from above. He stands amenable not only to the public opinion, but to the more awful tribunal of the great God.

The ruler who acts under the influence of these solemn Scripture truths, must be sensible that his eternal interest requires that he should rule in the fear of God. Such effectual security, both rulers and subjects derive from the influence of the Gospel. The former have need to beware, that they do not pervert a power to selfish purposes, which was committed to them to promote the general good. The latter have need to be no less cautious, that they do not resist an ordinance of God, by opposing the necessary exercise of civil authority.

5. When the Gospel, in any good measure, produces its effect on the minds of men, it begets the purest patriotism. It is a happy medium, between that selfish love of country which influences a man to desire the extirpation of all who do not belong to his own community, and the spurious philanthropy of some modern theorists which seems intended to dissolve the relations of kindred and country.

The pagan nations had each their tutelary deities; and these guardian gods of one people were supposed to be hostile to those of another. It were easy to calculate the effects which such a religion would produce on the temper and conduct of men. It would inspire them with surprising courage when fighting in the defense of their country, under the protection and with the aid of their chosen deity. Accordingly, the history of heathen nations furnishes astonishing instances of personal valor.—But at the same time it inspired them with a savage cruelty towards their enemies, at which humanity is shocked. It was an exterminating principle. This is an extreme of patriotism, if it may be called by that name, which, though it might produce some brilliant actions, is, nevertheless, baneful in its effects.

Another extreme no less pernicious in reality, though more plausible in appearance, is that of some modern infidels. They consider man in the abstract as the object of benevolence, without regarding the relations of family or of country; and that those who are the most remote, and beyond the region of our influence, have an equal claim to our affection and care, with our countrymen, or neighbors, or relatives. The fallacy of this principle will appear, when we consider that the sphere of man’s influence is circumscribed. He can be beneficial to but few. By being dispersed over an infinite surface, benevolence becomes wholly ineffectual. It is lost in the immensity of its object. This imaginary philanthropy tends to the subversion of society. It seems to be a chosen pretext to evade all the social and relative duties, and it terminates in unqualified selfishness.

The Gospel begets a patriotism which is adapted to the real state of mankind. It teaches them, that the God whom they worship is also the Guardian of other nations; and as his providence embraces all creatures so they are bound to embrace all in their good will; and that it would be criminal to desire the ruin of others, though not of the same community. But this benevolence is necessarily bounded in its operation.

As a man can actually benefit the members of his own family, his neighbors, or perhaps his countrymen, the Gospel recognizes these relations, and enjoins correspondent duties. It requires him to do good within the circle of his influence, rather than seek for remote objects which he cannot benefit. It begets the principle of patriotism in the heart, by teaching that none of us are to live to ourselves. Our calculations are not to terminate in our own interest or pleasure; that is, we must not make these our ultimate object; for if we take the example of the great Author of this religion for our model, we shall always be ready to sacrifice personal ease and emolument to the good of the community.

There are considerations to attach a pious man to his country, which can have no influence upon the mind of an unbeliever. His country contains not only the sepulchers of his forefathers, but also the institutions of their religion, the sacred temples where they sought the Lord, sang his praise, obtained relief in their distresses, and spiritual comfort to their souls. It protects not only his person and property, but the privilege of worshipping God according to the convictions of his own mind, and of enjoying those religious ordinances which to some are more precious than property, or kindred, or life itself. Nothing can animate him with equal zeal to repel an enemy who threatens to profane the sanctuary which his ancestors consecrated to God.

The truly patriotic sentiment of the Psalmist is exemplified in every good man, and his country’s peace is a constant subject of his prayer. “Peace be within thy walls, and prosperity within thy palaces. Because of the house of the Lord my God, I will seek thy good.”

The pagan nations contended with desperate courage in the defence of the temples and shrines of their gods; but their patriotism, as we have seen, was destructive in its effects. It had no mixture of that benevolence to the human race in general, which has softened the asperity and lessened the evils of war.

In short, where the Gospel has been published with success, it has produced an astonishing change in the views and manners of mankind; and this change is altogether for the better. Men of moderate capacity, who have received their principles from the sacred oracles, have more correct moral sentiments, and they are better instructed in the nature and extent of their relative and social duties, than heathen philosophers of elevated genius.

The Gospel presents enforcements to virtue inconceivably more efficacious than any other religion has furnished.—I have said, it has lessened the evils of war. It has also nearly abolished slavery; and God grant that it may perfect this good work. Where it has not wholly abolished this inhuman practice, it has certainly abated its severity; for the slaves of Christian masters are privileged beings in comparison with those who were so unfortunate as to be enslaved in pagan countries.

The time, and I fear your patience also, would fail, if I were to be more particular in stating the advantages which civil government derives from the influence of the Gospel.

I will now offer a few remarks on the conclusion which the Apostle draws in my text. Since we have a religion so completely adapted to the condition of mankind, a religion which furnishes such effectual aid to government, and which brings eternal life to individuals, ye do well that ye take heed to this sure word of prophecy, as unto a light that shineth in a dark place.

Perhaps I need not take a moment of the time in cautioning this respectable audience, that they do not conclude, from what has been said, that the principal excellence of this religion consists in its subserviency to the end of government.—Its great Author did not come down from heaven solely, or principally, to regulate the affairs of society; but for a more important purpose—to seek and to save that which was lost.

The Gospel is to be prized, chiefly because God has here given us all things which pertain to life and godliness, through the knowledge of Jesus Christ, who hath called us to glory and virtue. It is commended to our first attention as accountable creatures, because it contains those principles and discoveries which are able to make us wise unto salvation. Still it is a dispensation which embraces all the interests of mankind, in relation both to time and eternity: and since the aid which civil government derives from its influence is at once the most salutary and effectual, it is worthy of our regard in this respect.

If the positions which have been laid down in this discourse be true; and their truth may be ascertained and made evident by comparing the moral state of mankind in Christian and heathen countries; if mankind, under the influence of the Gospel, are made more discreet and conscientious rulers, or quiet and peaceable subjects, better parents, and more obedient children, benevolent masters, and faithful servants: If, I say, the Gospel produces such effects, it claims the regard of political men. Nay more, that man who would weaken or counteract this influence, immediately forfeits the character of a true patriot, and wise politician. He who aims, I will not say to promote the eternal interests of mankind, but the peace and happiness of the community, would not knowingly weaken the influence of one Gospel institution. He would carefully avoid every measure, whether he acts in a public or private capacity, which might lead others to disregard its institutions or doctrines.

I have already observed, that mankind must have religion; and I have the experience of all ages to justify me in the observation. I do not mean to say, that they are born with a holy disposition; that they are willingly subject to the law of their Maker; or that it is their pleasure to honor and serve him. But there are principles wrought into the very frame of their minds, which impel them to seek a refuge in some form of religious worship.

We admit, that there are times when all men do not feel the necessity of divine aid and consolation. This is the case with worldly minds in seasons of outward prosperity and inward quiet. If any, at such times, should suppose it would be as well with them if every principle of religion were extirpated, yet in the moment of impending danger they have other feelings. When the elements around them are thrown into confusion, and threaten destruction, something within impels them to consent to the truth that there is a God who ruleth over all; that it is infinitely desirable to possess his favor, and dreadful to meet his displeasure.

If then mankind have in all ages sought for some medium of intercourse with the Deity, the conclusion is unavoidable that wise men will choose and encourage that system which is best adapted to the condition of the human race, and which meets all their wants and difficulties.

The pious man will cordially approve of the Christian dispensation, as it clearly reveals his duty and supreme interest, and exhibits the desirable medium by which he may secure the divine favor. It administers those friendly warnings which are calculated to awaken him from his slumbers. At the same time promises are exhibited to allay his fears, lest they should drive him to a destructive issue. Here he finds safe ground for a humble hope and trust in the mercy of God. These are discoveries and aids which he cannot find in any other system of religion. When he finds such friendly warnings and instructions in the Gospel, that it contains a remedy for every moral disease, healing for every wound, duties prescribed for all the relations and conditions of life, and safe directions for every case of difficulty and doubt, he sees indications on every page of revealed truth, that it is the will of God, and bestowed, in mercy, on mankind.

But let a man even forget that he is a candidate for eternity; let him lose sight of all his relations, except his relation to society here; and in that case, if he be a friend to the peace and the true interest of the community, he will encourage the institutions of the Gospel; for surely such a man will encourage a religion which has the best tendency to secure the public safety, which opposes the most effectual restraints to the passions, and rectifies the disorders of the heart. He will be influenced, by these considerations, to pay a tribute of outward respect at least, to the institutions of religion, and encourage others also to respect and observe them.

To persuade mankind to abandon all religious principles, would be a fruitless attempt; it would be fatal, if not fruitless. Hence we see, that it is bad policy to counteract and weaken the influence of Christianity; for if mankind could be persuaded to believe that this is not important and essential to their peace, they are not persuaded to live without religion. They have only exchanged that which controls their criminal desires and intentions, for one perhaps more agreeable to their feelings, but inconceivably less safe. If they should be disengaged from the Gospel, they will feel at liberty to choose a system which will encourage them in immoralities, that will prove ruinous to themselves and to the community.—From these considerations, the Apostle’s conclusion in my text has a peculiar force.

We have a system of religion which afforded a refuge to our forefathers in seasons of the greatest peril and distress; a system which we have proved, and we have experienced its beneficial effects. It is to be imputed to the habits which have been formed under the influence of this religion, that we have been favored with civil freedom; and the state of society is more happy in this than in any other portion of the world. It is our interest to take heed to this system, until we can find a better, or at least one as good. It will be our wisdom to encourage the institutions of the Gospel, humbly receive its holy doctrines, and draw from this fountain of unerring wisdom, the principles of our conduct, whether we act in a public or private capacity.

Reflections of this nature must, at all times and under every circumstance, operate powerfully on every considerate mind; but they receive tenfold weight from the peculiar complexion of the present period. The political and the moral state of the world seems rapidly approaching to some momentous issue. The sudden changes which take place among nations astonish and alarm us, although we have hitherto been so happy as to remain distant spectators of the convulsions and distresses which other nations have experienced.

In the sudden vicissitude of human affairs, God is teaching mankind the uncertainty of worldly power. It seems that he will soon make it more manifest than ever, that he ruleth in the armies of heaven, and among the inhabitants of the earth; and that he giveth it to whomsoever he will. He is giving us sensible proof of the truth of Scripture prophecy, by visiting the nations with terrible judgments for their iniquities, as he has threatened.

We know not how soon we may share in the awful calamities which others have suffered. It will be remarkable indeed if we wholly escape. Should the wars and revolutions, which have convulsed Europe, reach this hitherto favored land, the civil government will need the aid of our holy religion, and individuals will need its consolations.

Whatever will be the result of those sudden and astonishing changes which take place in this age, we know it will be happy for those who have God for their friend. He will fix a mark upon his own people, that they shall not be involved in the destruction of the wicked. It will be safe for that nation where God has many true friends. Their prayers shall ascend for a memorial before him. It will, in short, be happy for that community whose members honor the institutions which Jehovah has ordained. He will be to them a covert from the tempest and the storm; for he never raised any expectations in the minds of his creatures which he will not fulfill.

I would not excite any unnecessary alarm, much less would I speak the language of despondence. That same kind providence, which has protected our country in ages past, will still protect us, if we have not forfeited the divine favor by ingratitude and disobedience. The Lord’s hand is not shortened that he cannot save. It has been our privilege to have descended from a race of men who were precious in his eyes; men who took early care to have the Gospel established among them, and made honorable provision for the education of youth.

It is doubtless to be imputed to the effect of institutions, that were so precious in the infancy of our country, that we have had so large experience of divine protection; that knowledge has been so generally diffused; and that there remains so great a degree of social order and happiness. We have been reaping the precious fruit of principles and habits which were planted and nurtured by the pious care of our forefathers.—Let us walk in their steps, and prove ourselves to be sons who are worthy of such fathers.

In these perilous times, let us take heed to that sure word which a gracious God has, in infinite mercy, spoken to us. Let us derive at once our principles and our hopes from the sacred volume. Let us honor its institutions, and be governed by its doctrines and precepts. Then may we hope that God will be our God, as he was the God of our fathers.

I proceed to such an improvement of this important subject, as the present occasion suggests.

We have assembled today, to seek the divine protection for those who are appointed to guard the rights and manage the public interests of the State. It is with pleasure that we see our rulers disposed to call in the aids of religion to the important object of legislation. It gives us confidence that they commence the business of the political year with suitable impressions of the insufficiency of human reason, and the necessity of direction from the Fountain of Wisdom.

We have endeavored to investigate some of the effects of the Christian dispensation on the habits and conduct of mankind; and to point out the degree of assistance which civil government derives from its influence. The general inference which results from this view of the moral tendency of the Gospel, is that which the apostle has exhibited. In whatever situation God in his providence has called us to act, whether rulers or subjects, ministers of religion, or people, it is our interest, as well as duty, to take heed to this holy dispensation as the ark of our temporal and eternal salvation.

When addressing myself to those whom I have represented as ministers of the Most High, I should be indeed inexcusable were I to betray any want of respect. But while I forbear to dictate to the rulers of the people on those topics which appertain to their office, and not to mine, I must not forget that I am set for the defense of the Gospel, and that it belongs to me, on this occasion, to vindicate this dispensation, the richest and the most desirable gift which a merciful God has bestowed on our world, and to recommend it to the regard of all men, whatever may be their rank and condition in life.

I will now apply the subject to the different branches of the government; and first to His Excellency the Chief Magistrate.

Your Excellency will be pleased to accept our cordial congratulations on this new proof of the public confidence and esteem. The providence of God has placed you in that elevated station, where your influence and example will have great weight in recommending to the regard to others that religion from which we have the happiness to believe you derive your own principles and hopes. It could not escape your observation, that the light in which the Gospel exhibits a Christian magistrate, ruling over a Christian and free people, is such as reflects great dignity on his office. His authority is derived from the highest source of power, and it will have a commanding influence over the reason and conscience of every good man. He is a minister of God for good, and therefore he holdeth not the sword in vain. But while this gives great weight to his office, his responsibility to the Supreme Ruler of the universe is proportionably great. The abuse of a power which is so sacred, and derived from such a source, will be followed by consequences greatly to be dreaded.

While an exalted station, like that which you fill, is always attended with trials, and especially in this convulsed age; and while the responsibility of such an office is great; you will feel that it is the more important that you take heed to that sure word of prophecy which the Christian Scriptures furnish; and that you take the principles of your conduct, as well in public as in private life, from the word of God.

Allow me to assure your Excellency, that, taking this unerring word for your rule, it will be a lamp to your feet, and a light to your paths. You will find support, equal to every trial, and safe directions in every difficult case: for though Jesus Christ did not undertake to legislate for mankind, yet he established those principles which are profitable to direct in all the relations of life.

We pray, Sir, that you may be favored with the divine direction, and experience divine support; and that, closing a long life, devoted to public employments, you may be approved as a faithful steward in the household of God, and be established in a state of everlasting rest.

Those who compose the Honorable Council, Senate, and House of Representatives, will permit me respectfully to recommend the religion of the Gospel to their regard, not only as men, but as rulers. I trust, that in the course of this exercise, it has been made evident, that where the principles of the Gospel have been understood and felt, they have given stability and effect to the government; though I will not pretend to have offered anything new.

If this truth, however, has been established; and we wish that everyone would satisfy himself on a subject of such moment, for it does not avoid, but invite, investigation; then the conclusion, which has been already suggested, is unavoidable.

It would be destructive policy, to counteract or weaken the influence of the doctrines and institutions of our holy religion. It would enfeeble the hands of rulers, and paralyze the nerves of government. It would disengage mankind from restraints which alone can reach the source of those evils that government was designed to recify, and leave them at liberty to adopt such system, for themselves, as would encourage them to commit every kind and degree of iniquity. It would, in short, set open the gates through which an overwhelming deluge of fraud, deceit, oppression, violence, profaneness, intemperance, and impurity, would pour in upon us, and lay waste this goodly heritage which our fathers left us.

We feel confident, Legislators, that none of you are disposed to try the desperate experiment. For should you weaken the influence of the Christian dispensation, or persuade mankind to abandon it, you have not persuaded them to abandon all religious principles. Such an attempt would be fruitless. It would be opposed by those hopes and fears which are wrought into the frame of every man’s mind. You only leave them to adopt such principles as will be infinitely less favorable to correct morality, and to the designs of civil government.

It is, then, far more safe, that we cherish the system which made our forefathers a respectable and happy people, and which has maintained among us, even to this day, a good degree of social order and happiness.—What then is the conclusion from these principles? It is obviously this—As men, and accountable creatures, we are all bound to respect the Sabbath, and keep it, and encourage the institution of preaching.

But you are called to act in another relation. An enlightened people have committed to your trust their most valuable temporal interests. In the discharge of this important trust, you will feel bound to take your principles from the oracles of unerring truth.—But this is not all. As political men, you will feel an additional enforcement to give all the efficacy in your power, by your personal example and official influence, to that religion which will strengthen your own hands as rulers, and which begets in the minds of people a confidence in government, and the principle and habit of obedience.

The recollection that you are called to legislate for one section of a community, the most happy and enlightened in the world, will naturally lead you to inquire by what means so much knowledge has been diffused, and so great a degree of social order and happiness has been maintained among us. If, in the result of such an inquiry, you find, as I am persuaded you will, that the happy state of society here, is in a great measure to be imputed to the divine blessing on the means of religious improvement, this will be a powerful inducement to regard and encourage these truths and institutions as the most effectual means to perpetuate our tranquility.

It is our prayer, that you may commence and proceed in the important business for which you are convened, under the divine guidance; that you may enjoy health and happiness; and when every earthly distinction shall be leveled in the dust, may you partake of the final rewards of good and faithful servants, in that Kingdom which will endure forever.

I conclude, with a few words to this numerous assembly.

This day, fellow citizens, exhibits to our eyes a sensible proof that our civil liberties are not yet wrested from us; and that the storm which has overwhelmed nations, and involved millions of our fellow creatures in want and wretchedness, has not yet reached us. The favors by which we are distinguished, demand our unfeigned gratitude to that Almighty Being, who holds in his hands the destiny of nations. Especially it becomes us to be the more thankful, that we are favored with a religion which reveals the whole system of our duty, and which is able to make us wise unto salvation.

I would devoutly hope, that in this assembly of people, who inherit the spirit of freedom, and many peculiar privileges, from pious ancestors, there are but few, if any, who wish that the principles of the Gospel were extirpated. If I were to address a congregation of this description, I would inquire, What advantage can you promise yourselves, should you succeed in your wishes? Would it make one soul more happy, or would it better the moral condition of mankind? Alas! if the Christian system should fall, the only remaining comfort of many would fall with it. I mean, those who are pinched with penury and want, and groaning under oppression, have nothing to make their condition tolerable, but those prospects of rest and peace beyond the grave, which they derive from the provisions and promises of the Gospel.

As to the moral state of mankind, as you weaken the influence of the Gospel, you will give a freedom and momentum to vice, that it will burst through every human restraint, and eventually dissolve the bonds of society.

In this age, infidels themselves begin to tremble at the result of their own work, and acknowledge that mankind must have religion. Public order and personal security require it. They find, that infidelity is an unnatural monster that threatens to devour its own children.

The present age has furnished melancholy proof, that when mankind are disengaged from the restraints of religion, they will go to greater excesses of violence than was expected. It is therefore generally conceded, that personal safety and public order absolutely require that some kind of religious institutions should be maintained. When we obtain such a concession that mankind must have religion, we ask, is it wise, is it consistent with prudence and correct policy, to reject that system which our forefathers received, or withdraw your support from those institutions whose salutary effects have been proved, until you have found some other system which you are sure will be at least equally beneficial and safe? It cannot be wise to hazard the experiment which promises no certain good, but much probable evil.

As you regard your personal happiness, and as you wish that your civil privileges may be perpetuated, let your choice always fall on those men to rule over you, who give evidence that they fear God, and regard his word and ordinances: and having chosen such men, give them your confidence and support.

Especially cultivate an acquaintance with the principles of our holy religion. Honor and observe its institutions. Such public calamities may come upon us, and we may experience such vicissitudes even in the present life, that we shall need all its consolations. In this we shall find a covert from the tempest and the storm. It will be our support under trials, our relief from distress, our hope in death, and our defense and joy in the eternal world.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!