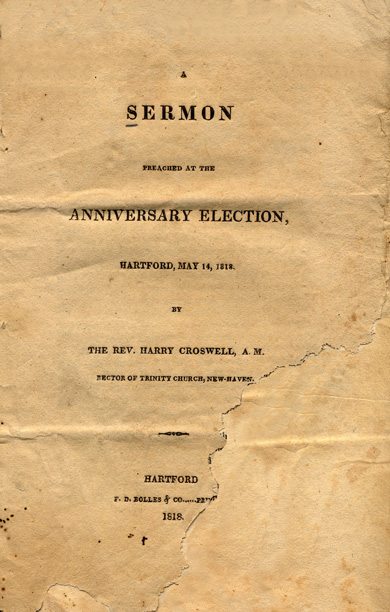

SERMON

PREACHED AT THE

ANNIVERSARY ELECTION,

Hartford, May 14, 1818

BY

TH REV. HARRY CROSWELL, A. M.

RECTOR OF TRINITY CHURCH, NEW-HAVEN.

Holding in high veneration, the character of our pious forefathers; feeling every disposition to treat the customs which bear the sanction of their authority, with deference and respect; I would not, without good and sufficient cause, depart from a course, which appears to have been ranked among the “steady habits” of my native state: nor would I, from an affectation of singularity, or on any other slight ground, dissent from opinions, which have long been considered by many as incontrovertible. If, therefore, on the present occasion, I shall appear to entertain doubts on the propriety of blending too closely, the civil and religious aspects of the community; or if I shall seem more solicitous to maintain the dignity of my profession, than to subserve any particular political interest: or if it shall be found that I am more ambitious to fulfill my obligations as a minister of Christ, than to offer the incense of flattery to any sect or denomination of men; I trust, you will do me the justice to believe, that I act under the influence of a solemn sense of duty—and that I am governed by no other motive, than a sincere desire to comply with the spirit of the precept, which I have selected for my text. Be this, however, as it may—I hope to find a defense of the sentiments which I may advance, and a justification of the course which I may pursue, in the example of our blessed Lord, in the case which drew this precept from his lips.

It will be recollected, that the passage before us was spoken by our Savior, in answer to a political question a question, calculated to involve him in disputes entirely foreign to his views, and at variance with the nature of his mission. It is not necessary now to refer all the circumstances of this case; nor to examine into the motives of those by whom the question was proposed to him; nor to enquire, whether the respectful terms in which it was expressed, were affected, or sincere:—“Master, we know that thou sayest and teachest rightly; neither acceptest thou the person of any; but teachest the way of God truly: Is it lawful for us to give tribute unto Caesar, or no?” [Matthew 22:16-17; Luke 20:21] It is sufficient to remark, what indeed must be evident to all, that the question was of a political nature, and involved a point on which the people by whom he was surrounded, were much divided. The Jews, on one hand, were extremely tenacious of their religious freedom; and, acknowledging no other sovereign but God, they considered their independence an essential point in their religion, and viewed every interference or imposition of the civil authority, as an infringement of their spiritual privileges. While, on the other hand, the adherents of the Roman government, who pertinaciously maintained the claims of the emperor upon the service and allegiance of the people, would have highly resented any denial of his authority, or any indignity offered to his sovereignty. The question, therefore, appeared to present insurmountable difficulties; and our Saviour himself viewed it as a temptation thrown in his way by those who proposed it, for the purpose of ensnaring him. “He perceived their craftiness, and said unto them, Why tempt ye me?” [Matthew 22:18; Luke 20:23] And then, requiring them to shew him “a penny” (a current Roman coin) he asked, “Whose image and superscription hath it? They answered and said, Caesar’s.” [Matthew 22:20-21; Luke 20:24] To which he replied, “Render, therefore, unto Caesar, the things which be Caesar’s, and unto God’s the things which be God’s.” [Matthew 22:21; Luke 20:25] As if he said—I perceive that you hold in your possession, and employ in your daily transactions, a coin, bearing the image and superscription of the emperor—that is, it is impressed with the dead or likeness of Caesar, and with his imperial titles. By receiving and using, and thus giving currency to this coin, you virtually admit the authority of his government; because it is by that authority, that this coin has received the stamp which it bears. Were you disposed to reject the authority of Caesar, you would refuse to give currency to his coin, which derives its nominal value from his image and superscription. Having thus tacitly submitted to his authority, you are bound in obedience to his laws, and to pay that tribute which he requires for the support of his government. You must render unto Caesar, the things which be Caesar’s. But, having done justice to Caesar, you are not thereby absolved from your duty to God. To Him, you owe that love, and reverence, and worship, of which no earthly power has a right to deprive him. It is that homage of the heart, which you cannot withhold from your Almighty Sovereign, without incurring the guilt of flagrant ingratitude and impiety. You must, therefore, also render unto God, the things which be God’s. “And they could not take hold of his words before the people; and they marveled at his answer, and held their peace.” [Luke 20:26] Such is the example, on which I rely, to defend the sentiments which I feel bound to express on this occasion. Such is the case, which I adduce to show, that it is both improper and hazardous for those who minister in holy things, to intermeddle with the party-politics if the times in which they live. Such is the authority, on which, I trust, the opinion may be maintained, that political and religious concerns are separate and distinct, and that they cannot, without manifest inconsistency, be blended together.

In the precept before us, our Divine Lord and Master as clearly defined the limits and jurisdiction of the two empires of heaven and earth. A distinguishing line is here drawn between our temporal and spiritual concerns, and between our civil and religious rights and obligations. Keeping this distinction constantly in view, therefore, I propose now to apply the principle embraced in the text—

First, to all classes and descriptions of men, collectively—

Second, to those who are in authority, as civil rulers and magistrates—

And third, to those of the clerical profession.

1. All classes and descriptions of men, are bound to render unto Caesar, the things which be Caesar’s, and unto God, the things which be God’s. If the subjects of the Roman empire, by possessing and giving currency to a coin which bore the image and superscription of Caesar, became obligated to submit to his government, and to pay the tribute which he demanded—it must be admitted, that every citizen of a free country, by accepting the protection, and receiving the benefit, of the laws enacted by the government, binds himself in honor, in justice, and in good faith, to yield obedience to that government, and to contribute to its support. A difference in the constitution or form of government, can make no difference in the principle. Is the citizen protected in the enjoyment of his rights and liberties—his property and his reputation? Does he pursue his proper calling, under the guardianship of the laws? Does he seek redress, when he is wronged? Does he sit securely under his vine and his fig tree; and does he enjoy his fireside unmolested? These are the only proper questions for his consideration, in determining what is due from him to his government. And if he can answer these questions only in the affirmative, if follows, as a necessary consequence, that he owes allegiance to the government. He cannot refuse an equitable return of that tribute or pecuniary support, which the management of the public concerns may require. We perceive, then, that the only manner in which we can render unto Caesar, the things which be Caesar’s—in which we can fulfill our duties and obligations to the civil government, under which it has pleased God to place us—is to yield to that government obedience and support, to submit quietly to its laws, and to contribute cheerfully towards its necessary and lawful expenditures. This appears to be a fair construction of our Lord’s precept; and the same principle is supported by the general tenor of the scriptures. And hence we conceive, that the minister of Christ cannot safely or justly inculcate any other political sentiment, amid the conflicting and discordant opinions of his fellow men. But if we owe thus much to Caesar—to our civil government—how much more do we owe to God! to that Almighty Ruler, who created us by his power, who preserves us by his providence, who redeemed us by his love, and who sanctifies us by his grace. We must not only obey him; but our obedience must be prompted by that love and gratitude, which carry the whole heart and soul into his service. We must be tributary to him: But instead of that perishable substance, which derives its value from the image and superscription of an earthly prince, the tribute which we owe to Him, is that living an immortal spirit, which is rendered invaluable, by the “form and pressure,” THE IMAGE, AND THE NAME OF GOD! The entire energy of the soul, must be poured out in reverence, in worship, and adoration, or we withhold that tribute which we owe to our Almighty Sovereign. We possess no treasure that can be substituted for this tribute—nothing that can exempt us from this obedience. No outward forms of submission—no cold or formal compliance with appointed ordinances—no zeal or fervency in support of peculiar doctrines or tenants—no vain-glorious or arrogant pretensions to exclusive sanctity—no sacrifices we can possibly make, save only the sacrifice of the heart, can prove acceptable to our heavenly Master. Nothing in this world—no created substance—nothing within the power of men or angels—can redeem the pledge, by which the soul is bound to God. If it can profit a man nothing, though he gain the whole world, and lose his own soul [Matthew 16:26; Mark 8:36]—so it would avail him nothing, were he to offer the whole world to God, and withhold his own soul. Thus, in the general application of the precept under consideration, we perceive how far the empire and jurisdiction of our earthly rulers extend, and where the claims of our heavenly Sovereign commence. We perceive the dividing line between our temporal and spiritual concerns, and between our civil and religious rights and obligations. If, in the one case, we withhold our obedience and support, we render not unto Caesar, the things which be Caesar’s; and so, in the other, if we withhold the entire devotion of the heart and soul, we render not unto God, the things which be God’s.

2. Those who are in authority, as civil rulers and magistrates, are bound, in their official capacity, to render unto Caesar, the things which be Caesar’s, and unto God, the things which be God’s. In making this application of the of the precept, the necessity of keeping constantly in view, the distinguishing line between our civil and religious rights and obligations, is sufficiently apparent. Because it is manifestly important to know, how far the civil ruler may interpose his authority in matters of a religious nature, without over-stepping the boundaries of his province, or usurping the prerogative of heaven. Touching this point, then, let us ask, whether the civil rulers of a commonwealth, composed of various denominations of Christians, can, consistently with the rights of all, exercise authority or control over those concerns which are strictly spiritual?—Or whether they can prescribe rules of faith, or modes or worship, for the great body of the people, without violating the spirit of this precept? Man is required to worship God, in spirit and in truth: and it has been already shown, that no tribute can be acceptable to the Almighty, except the free-will offering of a devoted heart. Indeed, it cannot be supposed, that services rendered by constraint—or in mere conformity to prevailing customs or habits—or to gratify the wills or affections of men—can be such a tribute, as a Being of infinite purity and boldness requires. And may not the interference of the civil government in matters of this nature, give such a bias to the mind, and impose such shackles on the will, as entirely to change the quality of the offering? Is it not the natural tendency of such an interference, to give to the religious services of the people, an appearance rather of subserviency to Caesar, than of devotion to God? If this be admitted, the civil ruler will undoubtedly hesitate long, before he will consent to exercise any authority or control in spiritual concerns. Aware that it is the prerogative of God, solely and exclusively to judge the heart; and aware also, that all men are accountable to Him alone, for the motives which govern them in their intercourse with heaven, the civil government will abstain from every measure, which may seem to usurp the rights of conscience, or which may obtrude on ground forbidden to any earthly power. All laws which tend, either directly or indirectly, to prevent the freedom of spiritual exercises—either by setting up distinctions among the different denominations of Christians—or by elevating one denomination above another—or by granting exclusive privileges to the one—or by withholding favors from others—will be carefully avoided. Nor will the government give the sanction of its authority to any habits or customs, which are likely to overawe the conscience, or cause the sense of responsibility which man owes to his Eternal Sovereign, to be transferred to his temporal rulers. The question, therefore, again returns—whether the authority of the civil ruler can, in any case, extend to matters of a religious nature? The peace and good order of society—the safety and tranquility of the people—undoubtedly depend upon the strict observance of those divine commands which prescribe a man his moral duties. Hence, it becomes the duty of the government, to found all its laws upon the moral precepts of the Bible: and the right of inflicting temporal penalties for breaches of the moral law, must follow as a necessary consequence. But all this, it will be observed, relates only to temporal affairs: and this interference is not designed, nor is likely to produce, any other than a temporal effect. It has no concern whatever with the heart or conscience. And although God may so overrule the measures of the government, as to render them instrumental in the work of conversion; yet it is not ordinarily expected, that outward punishment will produce internal renovation. Thus, then, we perceive, in this application of the precept before us, that the boundaries between the two empires can be distinctly marked. The utmost power of man, can extend only to outward and temporal concerns—while every thing relating to faith, reverence, worship, and devotion—every thing which depends on the feelings, affections, and sentiments of the inner man—belongs exclusively to God. We may therefore conclude, that the civil government cannot prescribe rules of faith, or modes of worship, for the great body of the people, without claiming for Caesar, the things which be not Caesar’s—without violating that great charter of Christian liberty, which was written by the Spirit of God, and sealed by the blood of the Savior.

3. But I am now, thirdly, to apply that precept in the text, more particularly to a class of men, whose political and religious rights and obligations, are not to be defined by the same rules which govern other cases, and whose temporal and spiritual concerns, cannot be measured by the same standard. I allude to those who are of the clerical profession. And in this application, it will be proper to consider the things of Caesar as the general concerns of the world, in contradistinction to those things which are spiritual. This class of men profess to be solely and exclusively devoted to God and his service. They profess to have relinquished the world, with all its concerns—its wealth, its honors, and its pleasures. They profess to be the ambassadors of Christ—the publishers of his gospel—the stewards of his household—the shepherds of his flock: and the acknowledge and confess, that after the entire devotion of their time and talents to the cause of their divine master, they still may prove unprofitable servants. From these men, then, Caesar, or the things of this world, can justly claim but little: and it may not be improper to enquire, in what way they may be liable to render unto Caesar, the things which be not Caesar’s and, consequently, withhold from God, that tribute which of right belongs to Him alone. If men, professing to have given up this world—shall still pursue its vain objects—shall still covet its perishable riches—shall still pant after its fleeing honors—shall still participate in its corrupting pleasures—do they not thereby depart from the plain import of their profession? Do they not injure the cause in which they are engaged? Do they not neglect their high and indispensable duties and obligations? And do they not violate both the letter and the spirit of the precept of our blessed Lord? Again, if men, bearing the commission of ambassadors of Christ, shall so far forget the allegiance they owe to him, as to listen to the overtures of any earthly power, or lend their influence to subserve any temporal interest—do they not thereby betray the sacred trust reposed in them, and treacherously surrender the rights of their master? Again, if these men, while pretending to publish and proclaim the gospel of truth, of peace, and salvation, shall, on the contrary, become promulgators and heralds of a spurious divinity, so mingled with the maxims of the world, and so degraded by the impurities of natural reason, as to obscure the truth, engender strife, and defraud man of his eternal hopes—do they not prove themselves the slaves of Caesar, though disguised in the livery of Christ? And again, if men, under the name of shepherds of the flock of Christ, shall appear more intent on feeding themselves, than on feeding the flock—if they shall neither strengthen the diseased, nor heal the sick nor bind up the broken, nor bring back that which was driven away, nor seek that which was lost—but shall suffer the sheep to wonder through all the mountains, and the flock to be scattered upon all the face of the earth—can such unfaithful shepherds expect any thing from their Sovereign, but denunciations and judgments? No—they cannot hope to hear the approving sentence, Well done, good and faithful servants! [Matthew 25:21] These are among the cases, in which the precept before us may be violated: but others, of a still deeper shade may be mentioned. If those, for instance, who have received the office of ministers in the church of Christ, shall engage in the political contentions and disputes of the day; and shall thereby foment party animosity and discord among the people, and disturb that peace and harmony, which they are bound, by the most solemn of all obligations, to cherish and maintain—how can they excuse themselves from the charge of perverting the sacred things of God, to the gratification of the unholy passions of man? And how much more culpable must they appear, if they shall carry their devotion to the things of the world and to Caesar, so such a length, as to pollute the temple and the pulpit, which are solemnly consecrated to the service and worship of Almighty God, by converting them unto forums, for political disputation! Thus we perceive the various ways in which they are liable to violate the precept. And we perceive the necessity of constant watchfulness and circumspection on their part, lest they should be found blameable, in rendering unto Caesar, the things which be not Caesar’s, and in withholding from God, the things which be God’s.

Having thus made the proposed application of the principle embraced in the text—to the people collectively—to the civil rulers and magistrates—and to the clergy—I shall observe the same classification in a few closing remarks.

Under a system of government, where the whole sovereignty of the state returns annually to the hands of the people, we seldom discover any want of attachment or respect to the civil rulers, or any disposition to withhold from hem, that obedience and support, which they have a right to claim. It is unnecessary, therefore, to ask you, my brethren, whether you render unto Caesar, the things which be Caesar’s. But there is a question of infinitely greater importance, which I am bound to impress home upon your hearts and consciences:—Do you render unto God, the things which be God’s? Does that Almighty Sovereign, by whose power you were created—by whose providence you are upheld—by whose love you were redeemed, and by whose grace you were sanctified—receive that tribute which he rightfully demands from his creatures? Have you given him your hearts? Have you surrendered your wills and affections to his guidance? Have you humbled yourselves before him? Have you poured out, on the foot-stool of his throne, the entire energy of your souls, in love, in worship, and adoration? Remember the immortal pledge, by which you are bound to the service of the Great Jehovah. Think not, that the external homage of a poor, perishing body, or the dross of this world’s wealth, can redeem that pledge. The treasures of this world will soon lose their value. The body, with all its powers, soon be mingled with the clods of the valley.—The dust must “return to the earth as it was.” But, “the spirit shall return to God who gave it.” [Ecclesiastes 12:7] Yes—while the body is mouldering in the grave, the immortal spirit shall still live. It shall again reanimate the scattered dust, on the morning of the resurrection: and it shall be held responsible before the bar of our Eternal Judge, for the manner in which every precept of holy write has been complied with. Have you rendered unto God, the things which be God’s? will then be the great and momentous question, for every soul to answer. And if the bare suggestion, now excites a momentary alarm—what must be the effect of such a question, amid the tremendous scenes of the final day—when the awful concerns of eternity are laid open to the view of the countless throng, who shall then surround the judgment-seat?

Honored and respected rulers! In expressing my sentiments on the subject before us, I have aimed at a plainness and frankness becoming my profession.—Allow me, however, to indulge in a hope, that I have not been so unfortunate, as to violate any rule of decorum, or overstep the limits of my province. With state affairs, I claim not the right, I feel not the disposition, to meddle. But for the holy religion which I profess—for the Church, in which I have the happiness to minister—I feel bound, on all proper occasions, to plead. Suffer me, then, to avail myself of this opportunity to express an earnest hope, that those who are called to administer the government by the united suffrages of a free people, will regard the religious rights of all, with an equal and impartial eye—that all denominations of Christians, may enjoy the privilege of worshipping God according to the dictates of their conscience, without the fear of incurring the displeasure, or forfeiting the favor, of their rulers—that our religious services may be free from every mixture of human policy, and every bias of worldly influence—and that the incense which ascends to the throne of grace, may be that “pure offering,” [Malachi 1:11] which constitutes the only acceptable tribute that man can render to God.

My brethren of the clergy! I need not apologize for the freedom with which I have spoken of the rights and obligations peculiar to ourselves, and of the importance of our Lord’s precept, when applied to our practice. The subject undoubtedly demands our attention. And as there are few occasions which call such a number of our profession together, I have deemed this a fit and proper opportunity for expressing, not only my own sentiments, but those held by the Church generally to which I belong. And as we have little reason to hope, that we shall all meet again in this world—you will permit me now, on parting, to add a word of exhortation. Let us, then, my brethren, endeavor to profit by the precept before us. Aiming to maintain the honor of our profession, and the dignity of the Christian ministry, let us not become instrumental in debasing them, by worldly mixtures. Let it be our study to stand aloof from those disputes, which disturb the peace and harmony of society. Let us not suffer ourselves to be drawn into measures, which may tend to promote the spirit of party among our respective flocks. Let us not give any reasonable cause for suspicion, that our influence is exerted in those political questions, by which the community is unhappily divided. Let us not put it in the power of the historian, to accuse us of descending from our high calling, to mingle in those dissentions, which are the offspring of human pride and passion. And, above all, let us beware that we do not defraud our Lord and Mast of his rightful claims. His kingdom is not of this world. He is jealous of his honor; and will no suffer his unfaithful servants to escape unpunished. We know the nature of our obligations. We know by what solemn vows we have enrolled ourselves under the standard of the Cross. We know that we stand pledged, by every thing dear and sacred to man, to preach CHRIST CRUCIFIED. Let us not, then, incur the dreadful quilt of preaching a religion without a Cross. Let us not glory, save in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ. [Galatians 6:14] By this cross, let the world be crucified unto us: and by the same cross let us be crucified unto the world.

And to God, the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost, be ascribed all the honor and glory, now, henceforth, and forever. Amen.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!