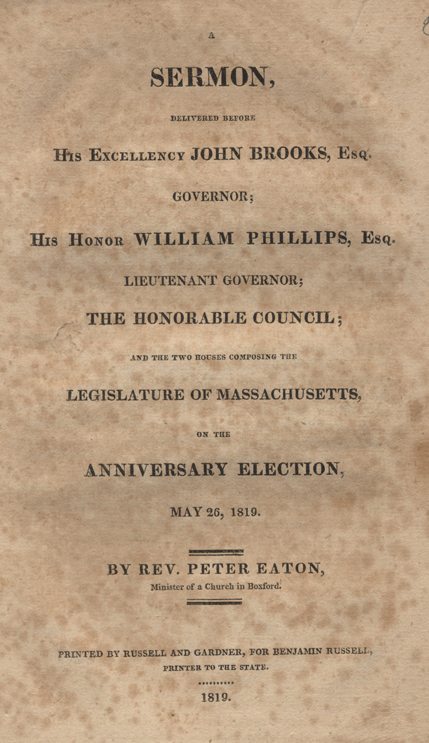

Peter Eaton (1765-1848) graduated from Harvard in 1787 and was a classmate of John Quincy Adams. He was pastor of a Church in Boxford, MA (1789-1845). The following election sermon was preached by Eaton in Massachusetts on May 26, 1819.

SERMON,

DELIVERED BEFORE

His Excellency JOHN BROOKS, Esq.

GOVERNOR;

His Honor WILLIAM PHILLIPS, Esq.

LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR;

THE HONORABLE COUNCIL;

AND THE TWO HOUSES COMPOSING THE

LEGISLATURE OF MASSACHUSETTS,

ON THE

ANNIVERSARY ELECTION,

MAY 26, 1819.

BY REV. PETER EATON,

Minister of a Church in Boxford.

Ordered, That the Hon. Israel Bartlett and William B. Banister, Esquires, be a Committee to wait upon the Rev. Peter Eaton, and, in the name of the Senate, to thank him for the Sermon, delivered yesterday, before His Excellency the Governor, His Honor the Lieutenant Governor, the Honorable Council, and the two branches of the Legislature; and to request a copy thereof, for the press.

Attest,

S. F. McCLEARY, Clerk.

It is the happiness of our constituted authorities, to assume the reigns of government, at a period of profound peace. Europe, which has drank of the cup of suffering, to the very dregs, is hushed to silence and repose. Peace, which is continually consolidating by time, has succeeded to noise, to tumult, confusion and blood. Our own country presents the most flattering prospects, and inspires the most animating hope. Conflicting opinions, and party prejudices, are yielding to the sway of better feelings; and we enjoy the reign of uninterrupted peace, increasing prosperity, and equal laws.

The speaker is happy, that his own inclination, and sense of duty, are in perfect unison. While the former would lead him to avoid all political discussions, the circumstances of the day forbid him, to combat party prejudices, or intermeddle with political creeds. It would be arrogance in him, to presume to dictate to our Legislators, the path of duty they are to pursue, or the measures to be adopted. We rejoice, that the civil affairs of the Commonwealth are confided to those, who are much better informed than himself; with whom, in the fullest confidence, we entrust our dearest privileges, and of whose capacity and disposition to guard them, the prosperous condition of the Commonwealth is the best proof.

Shall mine be the attempt, as it is the appropriate duty of my office, to exhibit the efficacy, the salutary influence, and enforce the principles of our holy religion. The tranquil state of the public mind, encourages this attempt: and I am animated with the hope, that my respected audience, are disposed with candor, to listen to such a discussion. For a guide to our meditations, I would select that passage of scripture, recorded in

ROMANS, III. 1, 2.

What advantage, then, hath the Jew? or what profit is there of circumcision? Much, every way: chiefly, because unto them were committed the oracles of God.

The apostle states and answers an objection anticipated from his preceding reasoning. This was the truth he endeavored to establish, that the want of privileges did not render the condition of the Gentiles utterly hopeless, nor the enjoyment of privileges, in which the Jews gloried, such as being the descendants of Abraham, and heirs of the promises, furnish them with a sufficient foundation of confidence. He expresses more hope of the virtuous heathen, than of the vicious Jews. If, then, the enjoyment of privileges would not avail to the felicity of the one, nor the want of them form an inseparable bar to that of the other, the inquiry was natural, what advantage does the enlightened Jew possess over the ignorant Gentile? The answer is, “chiefly, because unto them were committed the oracles of God.” This was a treasure granted to them, not vouchsafed to any other nation; a treasure, in the view of the apostle, of inestimable worth. Were the Jews favored, because they enjoyed the writings of Moses and the prophets; how much more highly are we favored, who enjoy the writings of the apostles, and of that Divine Teacher, who came from God?

The peace, order and prosperity of a nation, not less depend upon its religious than civil institutions; both are connected with the vital interest of the state.

It is well known to have been the object of certain philosophers, to prostrate religion, and bring it into contempt. So far from giving it the credit, of producing any salutary influence upon morals and the great interests of the community, it has been represented a mere political machine, managed by artful men, for the accomplishment of party purposes, and most fit to operate upon the weak, the credulous and the superstitious. It is my wish to rescue religion from this reproach. The object of the present discourse, is to trace the influence of religion upon the temper and conduct; especially, to exhibit the favorable tendency of the Christian religion, and consider its high claims to veneration and support.

My theme is noble and sublime; it not only claims the attention of the Divine, but of the Legislator and Statesman. What especially I regret it, my incapacity to do it justice.

If it be a fact, that religion is a delusion, the fruit of priestcraft and cunning; if it has no salutary influence upon the present life, upon our civil and literary institutions; if the hopes of future good which it encourages, are fallacious, let it be discarded forever. Let not a burden be imposed on the community, nor the credulous deceived by a fabulous theology. But, if it be a blessing, and one of the richest blessings of Heaven; if it has the best influence upon our present state, and future hopes, may it receive that support of which it is deserving.

We remark, that the professed religion of a nation, will have a powerful influence upon their temper and conduct, their customs and laws. The observation of the prophet may be admitted as a maxim; “all people will walk, everyone in the name of his God,” the general impression, in regard to the ruling Deity, cannot fail to have an operative influence, upon the temper and manners of the people. Hence, among Pagan nations, who have their thousand Gods, we find an infinite diversity of character, of customs and laws. The opinion formed of the presiding Deity, gives a cast and complexion to the worshipper. Some of the Pagans imagined heir Gods were vindictive and cruel. To appease them, when incensed, altars were continually moistened and smoking with the blood of human victims. Such were the Gods of Mexico, such the Gods of Carthage. How cruel, ferocious and barbarous were the people! Others viewed their Gods impure, the slaves of passion and lust. Shall we look for purity among the votaries, or wonder that temples were raised in honor of Venus? Will anyone hesitate to practice that, which is sanctioned by so high authority? Mercury was a thief, Jupiter a debauchee, Venus a prostitute, and Juno a scold. This we believe to be one reason of the low standard of morals among Pagan nations; the dishonorable views they had of their Gods. The natural tendency, then of the popular religion of the ancients, was to corrupt. So far from operating as a restraint upon the vicious propensities, it encouraged indulgence. The character of their deities was formed by their own polluted imaginations, and adapted to their depraved dispositions. The better informed, observing the superstition of the multitude, and its mighty influence upon their character and manners, incorporated with it certain virtues. To secure to them weight, to render them venerable, they were deified. Philosophers took an active interest in the religion of their country, and gave such a direction to the public mind, as would favor their own designs. Under their artful management, religion was made subservient to political purposes, and became an engine of state. Experience and observation had taught the wise and enlightened, that laws, the most rigorous, enforced only by human authority, were insufficient to restrain the ignorant populace. They were deeply impressed with the importance of an established religion; of something which should be held sacred by the people, to give security to civil institutions. It is believed the nation cannot be named, that enjoyed the blessings of a regular government, who were without a religion. That envied pitch of greatness to which ancient Rome attained, was not less owing to her religion than her patriotism. The favorable responses of her oracles, or predictions of the Haruspsex [ancient Roman religious official who interpreted omens], were considered as certain pledges of success. Lycurgus, having completed his system of laws, though not insensible to the weight of his influence and character; yet, dared not hazard them upon his own reputation, but repaired to the temple of Delphos, to obtain the sanction of Apollo. Not only, did the statesman avail himself of the influence of the popular religion, to give energy to law, and security to civil institutions; but the warrior had recourse to it, to enkindle the valor and encourage the hopes of his soldiers.

My business, however, is not with heathen mythology. Permit me to conduct your minds to that pure system of truth, with which we are favored, and trace its influence upon laws and customs, upon rulers and people. A cursory view of this system and its effects, must enhance its value in the estimation of every reflecting mind.

1. The Christian religion is favorable to the interest of science and literature. This remark is confirmed by the fact that all the science and literature in the world, at the present day, is confined to Christian nations. Who can place a finger, upon a spot on the globe, irradiated by science, where Christianity is not enjoyed? Wherever a door has been opened for the admission of Christianity, knowledge has followed in the rear; or, if preceded by science, it has meliorated the condition, and enlarged the views of the nations which it has visited. These are not vague assertions; we will recur to facts.

Many of the arts have been the result of necessity, and received their birth in the early ages of the world. The various condition of nations have led to inventions to remedy evils, which they experienced, or procure advantages of which they were destitute. The ancient Egyptians and Chaldeans, the Greeks and Romans have been justly celebrated for their discoveries and improvements; yet, in regard to general literature and science, how much do they lose in comparison with the moderns! In what did Egyptian and Chaldean learning consist? In what, the learning of the schools, in the early ages?

There is a prevailing habit, of attaching a kind of sanctity to everything that bears the mark of antiquity; names and discoveries are rendered venerable by time. We feel no disposition to derogate from the honor of the ancients, for they had to originate everything. Though they brought few things to perfection, they elicited light, they furnished a clue to direct future inquirers. Of their improvements in poetry, mathematical science, oratory and sculpture, they might boast. We also admire the systems of morals, established by their philosophers; not, however, so much on account of the perfection of those systems, as that they should have attained to such correct views, while they enjoyed very limited means of information. If in oratory they excelled, it is to be remembered, this is rather the language of nature, than art. The moderns have greatly improved upon their systems of mathematics and astronomy. If their Homer stands unrivalled, and their sculpture is unequalled; who will repair to them, for lessons upon jurisprudence, ethics, philosophy, or general literature?

Before the introduction of Christianity into Britain, Ireland, Germany, and Gaul, these nations were enveloped in ignorance. After enjoying its cheering light, how soon did they begin to emerge, from a state of gross darkness? It had a revivifying power and influence, upon every community which it visited. It found Europe drunk in barbarism. If we look back eighteen hundred years, what a spectacle is presented! Refined, enlightened Europe, was the habitation of savages. Nations who can now boast of their legislators, civilians, judges, philosophers, and theologians, were then the sport of druidical delusion. No sooner did the gospel shed its light on these benighted nations, than they were roused as from a slumber; the arts and sciences were cultivated, barbarous customs abolished, and the condition of nations meliorated. Its happy influence upon Ireland, was inevitably perceptible. The following honorable mention is made of her, after receiving Christianity. “The Hibernians were lovers of learning, and distinguished themselves in those times of ignorance, by the culture of the sciences, beyond all other European nations. They were the first teachers in Europe, who illustrated the doctrines of religion, by the principles of philosophy; among whom, were men of acute parts, and extensive knowledge, who were perfectly well entitled to the appellation of philosophers. They refused to dishonor their reason, by submitting it implicitly to the dictates of authority. 1 Who can doubt the auspicious influence of Christianity, upon the literary institutions of our own country? In proof of our position, that religion is friendly to science, we need only compare those sections of our country, where religious order and worship prevail, with those portions, which are destitute of religious instruction. It is somewhat curious to observe, how religion and literature go hand in hand. In those favored spots, where are to be found the most valuable religious institutions, you discover the most general information and improvement; where religious instruction is not enjoyed, what lamentable ignorance and darkness! Let us extend our views to our western regions, on which the sun of righteousness has scarcely dawned; we find the minds of the inhabitants rough and uncultivated, like the country in which they dwell. The dissemination of knowledge among the people, we believe to be friendly to the diffusion of religion. The mind being enlightened, is better enabled to discern the excellency of its spirit, principles, motives, tendency, and, of consequence, its value. Religion, in return, pays homage to knowledge, by fostering those habits which are favorable to its increase.

2. We will now trace the influence of religion upon government and laws. It is one of the firmest pillars and most effectual supports of civil government. Religious principle has the best effect upon rulers; it secures their faithful services, and is a guard and preservative from intentional error. The truth of the observation of Solomon, has been confirmed by the testimony of ages; when the righteous are in authority, the people rejoice; when the wicked bear rule, the people mourn. A sense of moral and religious obligation, is the surest earnest and pledge, that the legislator will enact equal laws, and that the judge upon the bench, will decide, without favor or partiality.

Religious sentiment in the ruler, not only encourages the expectation, that we shall realize our best hopes; not only impels him to consecrate his time and talents to the public good; but it has also the most salutary influence upon the governed; effectually binding them to the observance of law and order. The following considerations, may give authority and efficacy to law: self interest, popular opinion, fear of punishment, and religious sentiment. Self interest is an universally operative principle, pervading every breast, and acting with greater or less force. The requirements of public law and private interest, are sometimes in unison. When private interest enforces the observance of law, it cannot be clothed with greater authority. But, not unfrequently, they are at variance. The former, may be promoted by the violation of the latter. How often in this case, does experience teach, that human laws are feeble barriers in the way of the selfish passions of men? In vain you direct the views of those to the public good, who are destitute of patriotism.

It is acknowledged, that public opinion is a safeguard to human law and duty. Despotism wields an iron scepter; it can bear down all opposition; and enforce laws, the most contrary to public opinion. The community must yield to the yoke of oppression, and pay a forced homage to tyranny.

In a popular government, like that, under which we live, it is necessary that the laws should be accommodated to public sentiment, to secure to them a cheerful obedience. If condemned by public opinion, it is in vain to attempt to enforce them. Of this, the Grecian law giver was convinced, when asked, “whether the system of his laws, was the best which could be devised;” his answer was, “the best that the people were capable of receiving.” Under a free, popular government, a regard must be had to the temper, the feelings, and the habits of the people. When laws meet the public sentiment, that sentiment will give to them stability, yet not communicate to them a universal efficacy. The virtuous citizen can only obey for himself. What numbers are there, in every community, who are the enemies of all law, and impatient of every restraint?

A regard to character, may influence some to uprightness of conduct; yet, how many, are indifferent to personal reputation, and to public opinion; who neither esteem the applause, or fear the censure of the world? In this case, there remains only the lash of the civil law to operate a restraint. But even this restraint is removed, in the secrecy of retirement, when hope promises concealment of transgression. We contend, that religious principle only, will ensure the universal observance of public law. A sense of moral and religious obligation, is a more effectual security for upright conduct, than law, armed with the greatest terrors. Conscience exerts a mighty, an irresistible influence. She speaks with a voice he most deaf must hear. May it be further considered, it is religion only, which gives sanctity to an oath. It derives all its solemnity, all its binding power, and influence, from invoking an omniscient, ever present Deity, who abhors perjury. Lay aside religious principle, and what is there to secure the observance of an oath, but a principle of honor?

May I be permitted to repeat some observations of him, whom we delight to recognize as the father of his country. “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of patriotism, who would labor to subvert these great pillars of human happiness; these firmest props of the duties of men and citizens. The mere politician, equally with the pious man, ought to respect and cherish them. A volume would not trace all their connection with the private and public felicity. Let me simply ask, where is the security for property, for reputation, for life, if the sense of religious obligation desert the oaths which are the instruments of investigation in the courts of justice? Let us with caution, indulge the supposition, that morality can be maintained without religion. Whatever may be conceded to the influence of refined education, on minds of a peculiar structure, reason and experience both forbid us to expect, that national morality can prevail, in exclusion of religious principle.” 2

Of the importance of religion to society, public peace, and social happiness, we have been taught by a modern example. A great and powerful nation, within our recollection, have made an experiment; an experiment, the simple contemplation of which, causes us to shudder. A sect of philosophers, entertaining the most exalted opinion of human nature, and flattering hopes of that state of perfection to which man might be raised, by the cultivation and improvement of reason; viewing religion as a clog to his progress, and a bar in the way of attaining to the perfection of his nature; by systematic and unwearied exertions, at length prepared the public mind for an awful crisis. An explosion took place, the restraints of religion were burst asunder, and man was free. What was the consequence? Too shocking to describe! All the ferocious passions were let loose. A nation distinguished for its philanthropy and refinement, became a nation of monsters. The land was deluged with blood and crimes. A standing monument, a solemn warning to every nation, to guard against a similar experiment.

There is this imbecility in human law, which is irremediable; the offender must be convicted, the charge proved by indisputable evidence, before it can punish. The consequence is, that numerous transgressors escape with impunity. Religious principle, in this respect, possesses a decided superiority. It takes cognizance of every action, inspects the motive, operates in retirement, when secluded from the view of the world, as well, as when under public notice. It raises a tribunal in every breast, before which it arraigns the transgressor, and pronounces sentence upon secret faults, equally, with open offences. Human laws do not so much address the hopes, as the fears of men. They derive their authority more from the penalty with which they are armed, than the reward which they promise. They are framed on the presumption, that mankind are influenced much by fear, little by hope. This may be the case with certain abandoned characters; those who have reached a high pitch of depravity. Still, it may be admitted as a question, in regard to the great mass of mankind, whether hope or fear is the most operative. Human law is armed with a lash; it has little to allure. It is clothed with everything to alarm fear, little to inspire hope. Religious principle possesses this important advantage, it addresses both hope and fear. It presents on the one hand, glory, honor and peace; on the other, infamy, disgrace and ruin. As mercy is a distinguishing attribute of religious sentiment, its tendency is to divest laws, of all unnecessary rigor and severity. The criminal code of our own State, is not only an evidence of the enlightened views and humane feelings of our legislators, but of the prevalence of religious sentiment. To our religion also, are we indebted for the cultivation of all those mild and amiable virtues, which sweeten human life and adorn the human character.

That the Christian religion should have a salutary influence upon all those, by whom it is believed and embraced, would be a natural expectation. A system, so mild and beneficent, breathing peace on earth, and good will to men, cannot fail to have the best influence on those, who acknowledge its authority. But the fact, we believe to be unquestionable, that it has a beneficial effect upon unbelievers themselves. Their tempers are softened, their manners improved, their vicious propensities restrained by that very religion, they profess to reject and despise. Religion sheds her savory influence over a whole community; the beneficial effects are not confined to open, avowed friends; it is the parent of innumerable blessings to its enemies; gives a cast to the manners, and a tone to the morals of a nation. The infidel is profited by its effects upon others; and if not made better himself, is restrained from those excesses in vice, to which, otherwise he would proceed.

3. We will consider the influence of Christianity on customs and manners. Wherever its cheering light has shone, it has abolished the barbarous customs of sacrificing human victims. This practice prevailed, not only among the most ignorant Pagans, but the most enlightened nations; was not confined to a narrow compass, but was of universal extent. The impression was received, that such sacrifices were acceptable to the Gods; were efficacious in averting their anger, in conciliating their favor; and the more honorable the victim, the more acceptable to the Deity. The Carthaginians reduced to an extremity, in searching for the cause of their pressing calamities, imputed it to the anger of Saturn; Saturn, indeed, was angry, because, only the children of slaves had been offered to him in sacrifice. To appease the enraged Deity, to atone for past neglect, two hundred children of the first families in Carthage, were immolated upon the altar of the cruel God. We turn with disgust and horror from such scenes, to bless our God for a religion which has taught us better. Wherever the Christian religion has been introduced, it has abolished this cruel rite. Let it not be said, that the progress of civilization must claim the honor. Numerous instances might be adduced, in which the abolition immediately followed the introduction of Christianity.

Suicide, abhorrent to the better feelings of our nature, is expressly forbidden by the divine law. This practice was defended by the greatest philosophers and moralists of antiquity. Seneca, Plutarch, Quintilian, gave to it the sanction of their high authority. Their disciples were taught, either to despise the ills of life; or if calamities were pressing, to quit their post. Poverty, misfortune, dishonor, were considered sufficient to justify self murder; indeed, that not any were required longer to preserve life, than life was pleasant. At the present day, among some Pagan nations, we see the torch applied to the funeral pile, and the deluded follower of a false religion, expiring amidst the shouts of an infatuated multitude. We cease to wonder philosophers should countenance the practice, while their religion presented to them, little to hope, or fear from the future; especially, when it furnished no adequate motives to endure with fortitude, the trials of life. Nor is it a matter of surprise, that their disciples should regard suicide as an innocent act, when recommended by those revered for their wisdom, and honored for their virtue. If our religion has not cured the malady; it has checked the progress of the disorder. This divine philosophy furnishes us with motives to suffer with patience, and inspires feelings which revolt at the thought of self destruction. It teaches us to consider afflictions of a medicinal nature, designed to cure our vices and improve our virtues. The public mind is so far enlightened by our religion, the public feelings so far improved, that the public voice, as the only apology, pronounces the suicide a lunatic.

Christianity is justly entitled to the honor of abolishing that barbarous custom, the show of gladiators. This became a mere pastime at Rome. As their Gods were cruel, this belief served to render mankind obdurate; to stifle all the tender feelings of human nature. The impression was received and cherished, that departed heroes were delighted with carnage. For their entertainment, and to honor their memories, tragedies were acted at their funerals, and their graves bedewed with blood. In some nations, the aged were exposed a prey to the beasts of the desert; in others, infants, in whom the torch of life just lighted up, were by violent hands destroyed, and the murderer was the author of their being. Our hearts sicken at the recital of numerous Pagan rights, so abhorrent to the spirit of our religion.

Shall I, however, request your patience, while I mention one custom more, sanctioned by public opinion in the dark ages, now condemned, but still existing—dueling. We blush, that this relic of barbarism is still preserved. It originated in ignorance, under the false impression, that divine interposition would decide with rectitude. Competitors for office decided their claims with the sword; controversies between individuals were decided in a similar manner. This practice was encouraged by the highest authority of state. Their ignorantly, yet firmly believing, that truth and ignorance would be made manifest by the result, that divine interposition would decide with rectitude, pleads strongly in their favor. Their sin was the sin or ignorance. They did not contend under the false notion of honor; they were not hurried into the field by wounded pride, but it was an honest, sincere appeal to an higher power. Not so with our modern duelist. He outrages all law, human and divine. Is he a husband? He pierces the heart of the wife of his bosom. Is he a parent? His tender mercies to his children are cruelty. Is he a son? He brings down to the grave, the grey hairs of those he is bound to reverence and honor. He rushes to his solemn account, stained with blood. We are impressed with surprise, that a custom founded ignorantly upon principles which are now exploded, forbidden by human, divine law, and public opinion, which subjects families to such acuteness of sorrow, should still exist. While religion and humanity reprobate the custom; the tears of parents, widows, and orphans, plead against it; we are unable to find a single argument in its support. Is it such a virtuous and noble deed, shedding the blood of a fellow being, that it can wipe away dishonor? Standing as a mark to shoot at, will this save a sinking character? If this is honor, the assassin may die on the bed of honor.

If we contemplate the effects of Christianity upon the customs of war, it will appear that its influence has been highly beneficial. Since its introduction, wars have been less frequent. During seven centuries, the temple of Janus was but thrice closed. In reviewing the history of ancient nations, we feel almost compelled to subscribe to the sentiment, “a state of nature is a state of war.” Battles were fought with a savage ferocity. Victors became demons, deaf to the cries of mercy, and callous to the feelings of compassion. Captives were subjected to every kind of torture imagination could invent, and the scene closed with a carnival too horrible to relate. It is recorded to the honor of the “first Christian prince, that he offered a premium to the soldier who should save a captive alive.” Comparing the customs of Christian and Pagan nations, we learn how much we are indebted for our religion. It has enlarged the minds, improved the manners and softened the temper of men. Its spirit is pacific. To its influence may be attributed the tranquil state of Christendom and our own country. It has meliorated the customs of war, impressed the hearts of kings, who have avowed the purpose of governing according to its spirit and laws, honorable to their hearts, and an honorable testimony to our religion. Though Christianity has not proved efficacious in abolishing the custom of war; our hopes are sanguine, it will ultimately accomplish the object. Various appearances indicate the present, to be the dawning of a brighter day. The societies formed in different kingdoms, to give effect to the pacific principles of Christianity, prove an increase of enlightened views and good feelings. Success to those, the object of whose exertions, is to aid in the operation.

4. We beg leave to remark, religion is the surest basis of moral virtue. France has taught Christian nations, a practical lesson, upon this subject; and, by a melancholy experiment, has shown, how feeble are the restraints of moral virtue, separate from religious principle. These philosophers, who prevailed upon her to burst asunder the bonds of religion, were the perfect advocates of moral virtue, which furnishes the most powerful, operative motives to the practice. Would the moralist give the fullest effect to his system, let it be connected with religious principle.

“Talk they of morals!

Oh thou bleeding love,

The best morality is love to Thee.”

If pleasure and satisfaction may be derived from any particular course of action, an inducement is presented to pursue that course. “Happiness is our being’s end and aim.” It is the pole star, toward which human beings are directing their views. Virtue is the pursuit of one, because it promises happiness; sensual pleasure of another, because this is happiness. The greatest apparent good determines the choice of the mind. He who practices self denial, and he who indulges his vicious inclinations, both have the same object in view. And this choice must depend upon the moral complexion of the mind. That the practice of virtue affords pleasure to the pure in heart, is acknowledged; but not to him, who has contracted a high degree of moral depravity. In proportion to the increase of depravity, the moral sense is weakened, the power of conscience diminished, the mental taste corrupted, perverted; of consequence the pleasures of virtue lessened. Does the practice afford satisfaction to a pure mind? Revenge is sweet to a depraved mind. Does the enjoyment of one, consist in suppressing the benevolent feelings, in controlling the evil passions? The enjoyment of the other, consists in their gratification and indulgence. When, then, the violation of the principles of moral virtue promise happiness, what is there to give security to its laws, separate from religious obligation?

“But the beauty of virtue, its consistency with the reason and nature of things, must give to it a binding power.” What interest will the mass of the community take in philosophical discussions of the nature of virtue? Incapable of reasoning themselves, they will listen with no interest to a strain of reasoning from others, which they do not readily comprehend. Would you impress them, truth must be presented so clearly to the mind, that it may be discerned at the first glance, and so forcibly, that it shall be instantly felt. That persons of improved minds, of refined feelings and sentiments, are sometimes influenced to the practice of virtue, from a sense of its fitness, is unquestionable. The conviction produced in the mind, by their own reasoning, is operative. Yet, how large a portion of mankind are incapable of reasoning upon the subject; who are as insensible to the beauty of virtue, as the blind to colors. Display its propriety, utility, fitness; but what will be the effect upon minds indifferent to utility, and blind to moral fitness? That the obligations to virtue may be felt, it must be enforced by the high authority of Him who made us.

Permit me to conduct your minds a step further, to that eventful period, when time will close, and human distinctions be leveled. Who has not been a witness of the consolations religion has imparted, of the patience and fortitude with which it has inspired the mind, and the hopes it has cherished? We cannot recollect the tranquility of an Addison, his dying testimony in favor of our religion, without interest. To him, and to thousands, it has been of more worth, than crowns and diadems. Will it be objected that it is all a delusion? What an innocent delusion! a delusion, if you will have it so, which humanity forbids us to wrest from anyone, when it softens the dying pillow, and comforts the last sad hour. God forbid, we should deprive man of his last hope. The age in which we live, and the country in which we dwell, are distinguished for benevolent exertions to meliorate the condition of man. Systems are in operation to diminish the aggregate of human misery; to lessen the sufferings of the poor; to extend the means of moral and religious improvement, by a mild and gentle discipline; to reform that debased class of the community rendered obnoxious to her laws; to restore the lunatic to reason, and teach the dumb to speak. To the spirit of our religion are we indebted for these humane exertions, these benevolent institutions.

To Christianity it is objected, that it is found inoperative to a large portion of those by whom it is enjoyed. This objection cannot militate either against its truth or moral excellence. That it has a salutary influence upon all those by whom it is cordially embraced, must be conceded. Not having a favorable practical influence upon those, by whom it is rejected, no more disproves its value, than the virtue of a medicine is disproved, because refused to be taken. To test the value of a medicine, it must be taken; to test the value of our religion it must be received and practiced. The increased attention paid to sacred literature, must afford the most sincere satisfaction to the friends of our religion. Christianity has never suffered by investigation and research to the speaker, the supposition appears unreasonable, that no improvements can be made in theology; that we should rest precisely in the spot, where the first reformers left us. Indeed, they were not agreed. Luther, Calvin, and Zuinglius [Zwingli – Swiss Protestant reformer], differed in their conceptions of certain parts of Scripture. In the present age of literary improvement, when the best talents are employed in theological research, is nothing to be learned? Is every art and science susceptible of improvement, except divinity? It is not with Christianity as with mathematical science. The mathematics have for their basis certain unalterable principles. The theorems of Euclid admit of demonstration, being founded in nature. Improvements may be made in mathematical science, the superstructure may be enlarged, yet its fundamental principles remain unaltered. The process of reasoning is different, in establishing physical and moral truths. The former will admit that demonstration, of which the latter is not susceptible. Though the first grand principles, on which Christianity rests, is capable of satisfactory proof, yet, from that volume which contains our religion, numerous systems have been formed, the result of the inquiry and reasoning of fallible men. In mathematics, we recur to first principles; in theology we are often necessitated to recur to ancient customs, manners, laws. In fact, we know not the precise meaning attached to certain words. On this account, the field for improvement in sacred literature is widely extended. One important advantage must be the result of theological research; the better the Scriptures are understood, the more rational and consistent will be our religious system.

If such as have been stated, are the advantages of Christianity to the world, especially to our own country, we earnestly entreat for it the countenance and patronage of those who are advanced to offices of honor and trust. We recollect with gratitude, that the civil rulers of this Commonwealth have been uniformly friendly to religious order. This is recorded to their honor, as well as to the honor of the state. The greatest men, who have adorned any age, have been the patrons of religion. Christianity can claim in the number of her friends, an Addison, Boyle, Grotius, Bacon, Locke, Newton, Washington, Jones. What statesman will feel dishonored to be enrolled upon this catalogue? These men were not only her avowed friends, but placed themselves in the front rank of her defenders. To treat religion with cold civility and decent respect, is not all we ask of rulers. Permit us to say, we wish you to throw the weight of your influence into the scale. This will strengthen our hands, and encourage our hearts, who are her appointed guardians. And this, we believe, would be no less an act of patriotism than piety. My respected auditors cannot be insensible of the weight of their influence and example. Rulers may give a cast, a complexion, a tone to the body politic.

We beg leave to express our high satisfaction in seeing his Excellency again invited to the chair of state. Repeatedly clothed with the first office in the gift of the people, is the best evidence of their confidence. Nor could it fail to have been a source of pleasurable reflection to his Excellency, that under his administration, the asperity of political prejudices and party feelings have been yielding to mutual confidence. It has been the lot of no predecessor in office, to have witnessed the country in a state of greater prosperity. A consciousness of having contributed to allay the spirit of party, and increase the public prosperity, must afford comfort to the benevolent, patriotic mind. An administration, distinguished by enlightened views, guided by a wise policy, and animated by a spirit of moderation, has been duly appreciated by a discerning community. It is our prayer to God for his Excellency, that the evening of his life may be cheered and comforted, in beholding the rising glory, progressive improvement, and uninterrupted prosperity of a country, which has been the object of his best hopes, and shared in his best services.

We rejoice in those expressions of undiminished confidence, which his Honor is annually receiving from his fellow citizens. Religious sentiment being the best pledge of fidelity, we are assured that the Commonwealth will receive all the advantage of his talents and support. Though not insensible to the honor conferred by his fellow citizens, we are happy in claiming those high in office, practically subscribing to the sentiment. “A Christian is the highest style of man.” May a life, which has borne testimony to the truth, and in which so many of the virtues of our religion have been exhibited, experience its consolations, when earth and all its scenes shall be withdrawn. We tender our congratulations to the honorable Council, and are happy, that the important concerns of the Commonwealth are to share in the deliberations, and pass in review of those, who have been taught by experience, and whose knowledge of our civil and political concerns, must render them useful in Council.

The honorable Members of the Legislature, collected from various parts of the Commonwealth, bring with them the feelings and sensibilities, and know the wants of their constituents. Highly important and responsible is this branch of our government. You are not the minions of a chief, whose humble employment it is to receive projects of laws for discussion, or to adopt them without discussion. Yours, is the honorable, responsible office to originate them, to perfect them, to adapt them to the state of the times, to the habits and security of the people. Our protection and prosperity are intimately connected with this branch of our government. To you, we look for equal laws, security of life property, liberty, the encouragement of education, the preservation of order and protection in the enjoyment of that religion, the surest basis of morals, national order and happiness, and individual enjoyment. In the discharge of official duty, you have the example of statesmen and legislators of ancient and modern times. You will profit by their wisdom and their folly, their virtues and their vices. Such long experience have we had of the wisdom of our legislators, the equity of their laws, their careful attention to every part of the community, their attachment to order, learning, and religion, that with perfect confidence we commit to them our dearest rights. Happy the people who are favored with legislators, in whom, with so much confidence, they can confide. May God bless your labors, and your labors be rendered pleasant.

It has been remarked, that in America, our lofty mountains, majestic rivers, and extended forests, show that nature has wrought upon her largest scale. Our country affords the productions of every clime. Its rapid growth and increasing prosperity encourage the most flattering hopes. Blessed with constitutions of civil government, tested by experience, to be equal to the exigencies, and adapted to the habits and character of the people; favored with statesmen distinguished for talents, patriotism, and love of order; enjoying a religion, mild and beneficent; originating numerous institutions whose bounty flows in the channel of Christian charity, forming a swelling stream, which not only enriches and fertilizes our own country, but remote nations; with laws, just and equal, and numerous seats of science for the education of youth, what expectations may we not form of the rising glory of this western world? Some of the nations of Europe are on the decline; all probably have reached the zenith of their glory; while America is rapidly advancing to national eminence. May she be for a name and a praise.

Endnotes

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!