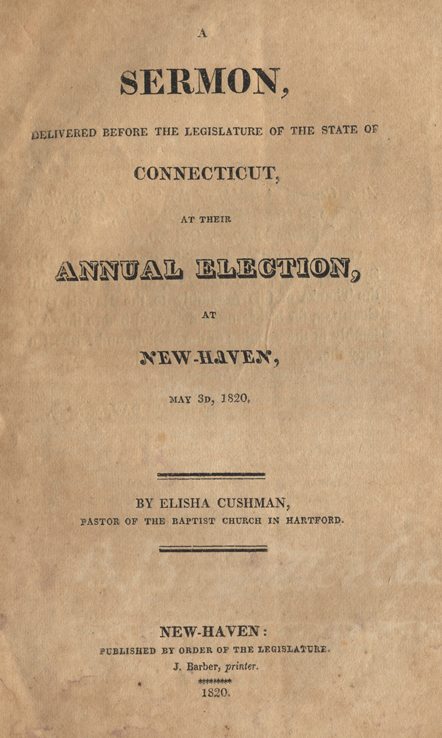

Elisha Cushman (1788-1838) was a carpenter before he decided to become a clergyman. He was pastor of a Baptist church in Hartford, CT. This election sermon was preached by Rev. Cushman in New Haven, CT on May 3, 1820.

SERMON,

DELIVERED BEFORE THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF

CONNECTICUT,

AT THEIR

ANNUAL ELECTION,

AT

NEW-HAVEN,

MAY 3D, 1820.

BY ELISHA CUSHMAN,

PASTOR OF THE BAPTIST CHURCH IN HARTFORD.

NEW-HAVEN:

PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE LEGISLATURE.

J. Barber, printer.

1820.

At a General Assembly of the State of Connecticut, holden at New-Haven in said State, on the first Wednesday of May, A. D. 1820.

ORDERED by this Assembly, that the Honorable Sylvester Wells, and Henry Seymour, Esq. present the Thanks of this Assembly to the Rev. Elisha Cushman, for his Sermon, delivered before this Assembly at the opening of the session, and request a copy thereof, that it may be printed.

Examined by

THOMAS DAY, Secretary.

—Who is the blessed and only Potentate—

I Timothy, vi. 15.

It was the design of the apostle in this text, and the preceding verses, to support the mind of his son Timothy under those discouragements which often overspread the prospects of the church. He well knew that the doctrine of salvation, by the cross of Christ, would be a scandal to those who were satisfied with nothing beyond sensible evidences, and, of course, that this doctrine would be made a subject of regard, or derision, according to its external prosperity or embarrassments. He was sensible that a system containing truths so humiliating to aspiring nature, imposing precepts so incongruous with the affections of the heart, and participating so little in temporal prosperity, would call forth the opposition of the world; and that through the infirmity of nature, Timothy would be tempted to despond under the reproaches to which his ministerial office would subject him, or to temporize with the popular influence which it was his duty to repel. He therefore enforces his charge to Christian patience and fidelity, by referring to the example of Jesus Christ, who before Pontius Pilate witnessed a good confession.

Jesus Christ has condescended to become the pattern, as well as the ruler of his people: He has exemplified every virtue which he commends for our observance: He lays no heavier burden upon his followers than he has endured himself; and perhaps no instance can be found in his life, which furnishes a more illustrious example of divine magnanimity in the deepest tribulation, than the one referred to by the apostle.—He was buffeted by his own people; hated and condemned by heathens; betrayed by one of his chosen apostles; denied by another, and forsaken by them all; and what was still more disheartening to human nature, he was apparently stricken, and smitten of God. But in the midst of all this, the afflicted Redeemer maintained his right to divine authority: He explained the nature of his kingdom, and referred who would admit no other proof of his dignity than the testimony of their senses, to an hereafter, when they should see the Son of man sitting on the right hand of the power of God.

This striking occurrence in our Saviour’s life, is calculated to inspire the most ardent devotion, to quicken us in the service of religion, to support our faith under the darkest human prospects, and teaches us to wait patiently for the victory over the world, when Christ, in his own time, shall shew who is the blessed and only Potentate.

That Jesus Christ is the blessed, and that he is the only Potentate, may be illustrated by a few following reflections.

I. He is the Blessed Potentate.

Were our reflections on the blessedness of Christ, to embrace all those divine excellencies which enrapture the celestial spirits, and which render him in the estimation of the church, the chief among ten thousands, and the one altogether lovely, we should transgress not only the bounds of prudence on the present occasion, but even the limits prescribed in the text; for if we consider him only in the character of a potentate, it is necessary to confine our reflections to the administration of his government, the blessedness of which consists in the purity and happy influence of his laws and the lenity of his dispensations.

1. The government of Jesus Christ is blessed on account of the happy influence of his laws on the morals of mankind.

Amidst the controversies which have arisen in the world respecting the necessity of a divine revelation, and its bearing upon the happiness of mankind, it has never been denied that virtue is preferable to vice, and that without the general prevalence of virtuous principles, social happiness cannot subsist: the important question has been, whether reason and philosophy, unassisted by the Christian revelation, are sufficient to influence mankind in the path of duty, and to fix a standard of morals adequate to the exigencies of the present state.

It must be acknowledged that reason and natural philosophy, have suffered in common with revealed religion, from the false pretensions of superficial professors. The tide of popular opinion, the sensual appetites, and the ambition of self interest, have each in their turn, held dominion over the human mind, under the title of reason; and in many instances inculcated principles disgusting to common sense. This accounts for the absurdities of that notorious infidel, 1 who after having resorted to the scriptures to justify and establish his theory of the rights of man, was taught by his reason to disbelieve the authenticity of that holy volume, and to impugn its sacred doctrine. This accounts also for the inconsistencies of a thousand others, who professing themselves to be wise, have become fools.

It is through the aid of reason that divine revelation commends itself to every man’s conscience; its precepts through this medium impress the understanding, and find an avenue to the heart. It is therefore equally repugnant to truth, and a departure from Christian candor to disparage the utility of reason, upon no other authority than the foibles of superficial beings, no less irrational in their notions than they are vicious in their lives. The power of reason and natural philosophy are nowhere more highly estimated than in the holy scriptures. Natural philosophy sets before the understanding a portrait of those divine perfections which claim the homage of the heart; reason, unbiased by the depraved affections, acknowledges the justice of the claim and ratifies the law of moral obligation: The invisible things of Him from the creation of the world are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even his eternal power and Godhead. So clearly were the perfections of God manifested to the heathens, that they are said to have known him; and so forcibly was their obligation represented by rational inference, that they were declared to be without excuse: Their being given over to a reprobate mind, was not because they adhered too closely to the dictates of reason, but because they DID NOT LIKE to retain God in their knowledge.

But after all the instruction imparted by the light of nature, it still remains a question, whether there be virtue enough in the human heart, unawed by the realities of a future state of retribution, and uninfluenced by the Spirit of God, to render that obedience to the Divine Being which reason dictates, and which conscience approves. On this question every candid man, acquainted with his own heart, will decide in the negative. It was the fault of the heathen philosophers, that when they knew God, they glorified him not as God.—It is the embarrassment of the Christian, that when he would do good, evil is present with him: and it is a fact, apparent on the very face of the world, that where the doctrine of a revelation is either denied or unknown, the dignity conferred upon human nature in creation, is debased by sordid habit; the understanding, capable of retaining a just knowledge of truth, is darkened by evil affections; and the morals proportionably corrupted by sensual lust.

The adversaries of Christianity, to commend the fruits of their own principles, have found it necessary to impress with the signet of virtue, many of the dissipating amusements and indulgences of life; and where vice has been too glaring to admit of an apology, it has usually been discarded in general terms; or, through fear of finding its true pedigree, ascribed to some indefinite cause. Where the greatest corruptions are allowed to be treated in this superficial manner, and their indirect fruits honored with the appellation of innocence, it is not difficult to rear a temple nominally to virtue, and to paint its foundation with the colouring of philosophy. But if social happiness depends upon the principles of morality, its extent will be in proportion to the purity of those principles, and therefore can never be complete so long as the standard of morals is biased by a depraved taste.

The task assigned to the advocates of truth at the present day, is not so much to prove that the doctrine and precepts of Jesus Christ are beneficial to mankind, as to represent them to be the only system of peace and good will to men. Open infidelity of late, seems in many instances, to dread that publicity she once labored to maintain; her hideous portrait, and disastrous effects, have excited the apprehension of many modern ‘free thinkers,’ and driven them back to the hypothesis adopted by Lord Herbert and others, that Christianity, though a friend to virtue, is not its only source.—On this ground the peculiar claims of Jesus Christ are now disputed, and on this ground the Christian is bound to contend with error.

It is a mark of human depravity, that whilst the pure streams of morality are conveying peace to the Christian world, their source is so generally unknown; as if, because God sends his rain upon the just and unjust, it were difficult to ascertain whether his blessings are designed as a reward of virtue, or as an encouragement to disobedience; or because the Christian and the infidel are made to enjoy the blessings of good order in common, it were doubtful whether these blessings of good order in common, it were doubtful whether these blessings spring from Christianity, or from atheism, or from some intermediate principle, or indifferently from them all.

The Christian religion must stand or fall alone; it can never hare with the systems of men, in the reputation of destroying the vices of the world, and restoring the happiness of mankind. If the scattered fragments of morality, collected from mere human maxims, can produce the effects for which we depend on the gospel of Jesus Christ, they deserve our superior regard, and our entire confidence: for they evidently have this preference—they impose no cross, they conduce to the end designed by revealed religion, and supersede the means; to concede a part therefore, is to yield the whole. If the requirements of Christianity are not necessary to the restraint of the passions, and the promotion of human happiness, it is justly chargeable with unwarranted austerity. It is conceded that the morality of Jesus Christ imposes a rigorous discipline upon the passions: In addition to prohibiting those notorious crimes which the votaries of no system whatever are willing to avow, it attacks the buddings of iniquity, and forbids those apparently trifling indulgences, the greatest evil of which consists in the mis-improvement of life, and their tendency to ripen into more flagrant vice. It requires not only that we abstain from murder, adultery, theft, &c. but also that we should be transformed by the renewing of our minds; that the affections should be set on things above; and that our conversation should be in heaven. But the very circumstance that renders these demands unwelcome, proves them to be of the utmost importance, by illustrating the opposition of the heart to that which is of itself just and good. The vitiated taste of man requires a remedy—and happy for us if an antidote, nowhere to be found on earth, is given us from heaven. The holy scriptures are wisely adapted to our fallen situation; they excite our hopes and fears, by revealing a future state, where righteousness is crowned with glory, and where iniquity is clothed with shame; they exhibit in the person of Jesus Christ a perfect model of excellence, calculated to elevate the mind above the level of itself; they furnish the only sufficient motives to restrain the sinful appetites; and where they are not enjoyed, a chasm is left in the moral world which no system, merely human, has ever been able to fill.

The individual and social happiness resulting from a life of holiness, might indeed convince the judgment, but can never win the affections; the present indulgence of a vicious appetite leads to a procrastination of that course of sobriety which reason declares essential to durable peace.

Nor can a sense of honor command the heart; a respect for public reputation might avail something in regulating the habits, if virtue only were approbated in the world, and vice universally despised: but this is not the case—many things highly esteemed among men are an abomination in the sight of God; as there was scarcely a species of iniquity among the ancient heathen which was not sanctioned by the example of someone of their gods, so there is scarcely a vice practiced in the world, which is not justified and applauded by some portion of mankind. What assistance therefore can rational argument obtain by appealing to a sense of honor, when the name of honor is associated with the grossest violations of order; when even the deliberate barbarities of the duelist receive applause from a considerable part of the world, and sometimes apologies from the Christian himself.

No less ineffectual are the tenderest sympathies of nature to prompt to a virtuous life. Go tell the unfeeling oppressor, who keeps back by fraud the hire of his labourers, that by his conduct he distresses the poor, and that by his example he contaminates the world; adjure him by the tenderest regard he feels for the happiness of his fellow men, to cease from his misanthropy and to become the benefactor of mankind. Go entreat the barbarous assassin to abandon his cruel purpose; tell him that he is spreading misery through the unhappy community by his nefarious practices; that whilst he is plundering the mangled corpse, he is breaking a widow’s heart, and robbing a helpless offspring at the same time, of their father and of bread: exhort him by appealing to his humanity, if he cannot meliorate, not to multiply the sorrows of life. Expostulate with the ambitious warrior, and remonstrate against the injustice of his campaigns; tell him that while he is building his throne with the bones of his subjects, he is filling the world with woe; represent to his imagination those scenes of horror which he has often with cold insensibility realized; the rural abodes of peace thrown into confusion by the din of arms—the verdant fields stained with human blood—Rachel weeping for her children, and searching for her first-born among the undistinguished heaps of the slain—pillaged edifices in flames—a merciless band let loose among the affrighted remnant of a slaughtered community.****We will turn from this dismal picture; it shades are too dark to be traced here; we will only say, it is impossible to excite generous sensations in a mind inebriated with the love of the world; it is impossible to awaken sympathy in a heart chilled beforehand with the frost of death.

Through the obstinacy of the human passions the most powerful motives fail to produce all the good requisite to human happiness: the heart must be affected before the character can be radically renewed.—But what are the motives drawn from human sources, compared with those derived immediately from the mouth of God—by whose word consequences more dismal than the miseries of life are affixed to the crimes of men? By his word the transgressor is taught that he stands in relation to God as well as man; that the magnitude of his offence is proportioned to the value of those interests which the law he has violated was designed to guard; that in trespassing upon the rights of his neighbour, he has opposed the honor of Jehovah, and that he stands before the tribunal of his eternal Judge, charged with guilt, which nothing but the blood of Jesus Christ can absolve. This revelation of a future state of retribution is the peculiar energy of the gospel, and evinces its emanation from a blessed Potentate.

As Christianity possesses a superior energy above every other system to awaken the conscience, so it has this peculiar virtue—its spirit quickens and sanctifies the heart.

It has been considered a question of importance, whether a community, favored with the knowledge of the gospel without its power, would surpass in virtue the heathen nations, who have only the light of nature, and even that eclipsed by a train of superstitious rights. Through the goodness of God a decisive experiment cannot be made, for wherever the unadulterated truth of Christianity has been faithfully dispensed, the agency of the Holy Spirit has given it access to the hearts of many, who by their pious example have in a great measure regulated the habits of the unconverted. If we can form a probable conjecture however, from the morals of a people whose faith is merely intellectual, we shall find it unsafe to rest our hopes upon a speculative religion of any kind. It is with the heart man believeth unto righteousness, and with the mouth confession is made unto salvation.

It is observable that St. Paul in his second epistle to the Thessalonians, has considered the moral tendency of heathenism and of papal superstition in every material respect the same. After extending his reflections forward to that period when the man of sin should be revealed, exercising usurped dominion over the consciences and rights of men, he immediately turned his attention to the persecutions of Nero, Domitian, and others, and observed that the mystery of iniquity did then already work—that there was no essential difference between that and the future period; only, that the pagan horn, which then ruled the Roman empire, would retain its power until it should be overcome; only he who now letteth, will let until he be taken out of the way.

This sentiment of the apostle was fully substantiated by the subsequent history of the church. The reins of government were held by men, who, though they adopted the faith of Christianity, made no other use of it than to accelerate their worldly projects; and being altogether unaffected in heart with the principles they avowed, were left without restraint, both with regard to their public edicts, and their private deportment.

The conversion of Clovis, king of the Franks, to the Christian faith, must have been considered an event highly auspicious to the church of Christ, had the doctrine he espoused held its dominion over his princely ambition, and his sensual appetites; but having embraced Christianity in the first place, to facilitate his worldly enterprise, who could suppose that the principles he had adopted would restrain his lusts, or smother the pride of his heart, or withhold his arm from shedding human blood?

By the addition of superstitious rites to the ordinances of the church; by the union of worldly maxims with the precepts of Christ, and especially by the prostitution of evangelical truth to serve the policy of state, fornication was early committed with the kings of the earth, and by an illegitimate increase of the church, thousands became nominally the sons of Zion, who were never lawful heirs to her incorruptible inheritance. A host of avaricious priests were spread over the world, who, not contented with their own personal gratification, encouraged in others the basest corruptions with the pretended authority of heaven, and exhibited the fruits of their arrogance as an article of merchandize. Had the morality of the church of Rome corresponded in purity with her doctrine, (which would have been the case, if her doctrine had been inculcated with reference to its original design,) less occasion would have been given for the enemies of the cross to charge the most salutary principles with the worst effects, and to arm themselves with the enormities of hypocrites against the power of evangelical conviction.

Divine truth, notwithstanding the abuses it has suffered, still retains its excellency, and extends its influence; where it is exhibited only as the test of worldly emolument, it may produce but little salutary effect: but where it is disseminated as the seed of piety, and cultivated accordingly, it will, through the spiritual influence of its great Author, soften the obdurate heart; it humbles that pride and subdues those passions which produce the greatest evils of life. Under its sacred energies a radical change is wrought in the whole man; the wandering sinner is brought to the communion of his God at the mercy seat. The persecuted saint, so far from retaliating the wrongs he suffers, moved by the love of God, and drawn by the love of his neighbour, prays for the blessing of heaven on the head of his enemies. The veneration and respect of the unconverted are gained; the realities of eternity are preserved in remembrance; the conscience is kept awake, and the general habits of mankind regulated. If we extend our reflections abroad, and contemplate the situation of those miserable beings who sit in the region and shadow of death, we are shocked at the contrast presented to our imaginations between light and darkness; the mind sickens at the thought of being left to make its way through this enchanted maze without a guide, and to form its ideas of futurity from mere conjecture. We bless the light of revelation which beams upon the bewildered mind, and under the genial influence of the gospel, we recognize the administration of a blessed Potentate.

2d. The lenity of Jesus Christ towards his subjects, is a further illustration of the blessedness of his government.

The humiliation and sufferings of the Redeemer have procured him the rightful scepter of the vast universe; all power is given unto him in heaven and in earth; he is set as a king upon the holy hill of Zion. He has however referred us to a future period for a full and visible display of his vindictive authority; his government is at present characterized by unexampled mildness.—A bruised reed he shall not break, the smoking flax he shall not quench, until he bring forth judgment unto victory. The suspension of those judgments with which idolatrous and oppressive nations have been threatened, is one of the numerous instances of divine compassion. The cry of innocent blood ascending from under the altar, though by no means a subject of indifference to him in whose cause the holy martyrs suffered, is nevertheless deferred for a season, through the divine forbearance; and where injured goodness has forbid a further delay, and the general good, connected with the glory of God, has demanded immediate vengeance, he has either delivered his servants by a premonition of his designs, or graciously supported them through their trials, and received them to himself. His lenity is no less visible in his dealings with individual sinners; though they have transgressed his law, and abused his gospel, he still protracts their space for repentance, and enriches their forfeited lives with the blessings of his bounty. He watches the first emotions of godly sorrow; he listens to the first sigh of repentance, and early answers the supplications of the contrite sinner, with the forgiveness of sin. Or if the stout-hearted transgressor refuses to bow to his scepter, and persists in rebellion until the Lord Jesus shall be revealed from heaven in flaming fire, he assigns no heavier penalty in the world to come, than to reap eternally what has been voluntarily and deliberately sown in time.

II. Jesus Christ is the only Potentate.

The sentiments of the apostle were too well understood to admit of such a construction as would preclude the exercise of civil authority. Although he has in the text represented Jesus Christ as the only Potentate, he has elsewhere enjoined subjection to the higher powers on earth, and declared them to be ordained of God. The institution of civil government, so far from contradicting the supremacy of Jesus Christ, directly confirms it.—The precariousness of human power, evinces its derivation from a source higher than man, and shews at once its dependence on the King of heaven. Two arguments only are proposed to illustrate the entire sovereignty of Jesus Christ. The first drawn from the fate of nations; the other from the progress of that truth of which he has styled himself the king.

1st. The prosperity or declension of empires has ever been according to the extent in which the spirit of Christianity has characterized their government. The history of nations establishes the fact that the restless ambition of princes to enlarge their dominions, and to extend their authority by injustice, has been as repugnant to their own interest as it is contrary to the spirit of Christ. It has produced evils which the wisest policy of state could never avert; it has ever exposed them to the resentment of potentates equally as ambitious as themselves, and they have found at last, that a part of their glory was purchased at the ultimate expense of the whole.—Personal indulgence in those sensualities which the Christian religion so strictly forbids, by its own natural tendency paralizes the arm of temporal dominion, and often conducts to an ignominious death. Wherever the pride of monarchs, cherished by the illusive splendor of royalty, has led them to forget their dependence, and to trifle with the liberties of their subjects, they have blindly courted sedition, and provoked insurrections fatal to themselves and destructive to their government. Specimens of these uniform effects of pride and sensuality are furnished in the history of the Greeks, of the Romans, and of some of the more modern kingdoms of Europe, and substantially prove, that righteousness only, can for any length of time, exalt a nation. Could even the establishment and support of the Christian religion by the strength and emoluments of state, atone for the personal violation of its precepts, governments long since dissolved, might still have retained their glory and their strength; but experience has proved that nothing short of Christian humility and obedience, can meet the favour of Him to whom all are subject, and on whose smiles all are dependent for temporal prosperity and eternal salvation.

2d. The supreme power of Jesus Christ is illustrated in the success of his doctrine and institutions.

The prosperity of the Christian religion from its early dispensation, and especially for a few years past, has been too obvious to escape the notice of men of ordinary information, and supersedes the necessity of a particular detail of events. It has gladdened the hearts of its friends, and awakened the jealousy of its enemies. A cursory reflection however on the multiform opposition which it has withstood, and the multitudes it has gained to its standard, is sufficient to convince every mind that is not guarded against the light, of the excellency of its nature, and the divine power of its Author.

In the first triumphs of Christianity, Jesus Christ was the only potentate. His own arm brought salvation unto him: The kings of the earth stood up, and the rulers were gathered together against the Lord, and against his Christ. The most violent persecutions were raised against the disciples of Christ, and what could not be effected by formal indictment, was attempted to be done by fraud; but notwithstanding all that was done (and but little more could be done) to destroy the followers of Jesus, their numbers increased, and their religion flourished.

The immortal principle of piety, which had outlived the rage of Jews and Pagans combined, was next doomed to suffer the weight of papal vengeance. The history of the church, at one view, seems to represent those professors of the Christian religion, who had escaped the pagan executioner, reserved only for the rack, the fire and gibbet, prepared under the pretended authority of their own Master: while on the other hand, it represents them multiplying in proportion to their trials, and the very flames in which they expired, served only to enlighten the world, and develop the hypocrisy of their persecutors.

At length in her turn, arose that subtle adversary, justly styled modern infidelity; for the realities of a future state, which ancient rationalists acknowledged probable, she professed authority to deny; and having learned in the fate of the church of Rome, the consequences of propagating licentiousness with a pretence to divine authority, chose to distribute her indulgences with human credentials, under the forged signature of reason and philosophy. The open attack made upon Christianity at the time of the French revolution, threatened evils from which no human arm could deliver; but yet so far from being overcome by her enemies, the church gained extent and glory by the contest; infidelity became less successful in open combat, than it had been by clandestine efforts to make disciples in the dark; its noisy clamour awoke the slumbering talents of the friends of truth, and the result became, as might be expected, through the strength of her sovereign Potentate, prosperous to the church. Must not a religion which has withstood all these enemies be divine?

Jesus Christ has also displayed his power in the multitudes who have voluntarily consecrated themselves to the promotion of his religion.

There are two classes of people gained to the cause of the Christian religion, who we can hardly suppose would have embraced it, if they had not been influenced by its sacred energy. Among the first class are those earthly potentates, who are surrounded by the temptations and encumbered with the concerns of the court. Among the other, are those who from infancy have been trained up in idolatrous superstition.

It is not necessary to the present object, to investigate the motives of those, who amidst the grandeur of state, have availed themselves of their eminence in life, to commend the doctrine of the cross; admitting the motives of honour and self-interest, with which they are often charged, be justly applied—it may be with propriety asked, Whence happens it, that it is now the honor and interest of kings to recommend and aid a religion which it was once their glory and their policy to suppress? How happens it that hypocritical princes have found it necessary to assume the name of Christian, to secure the loyalty of their subjects, and gain the applause of the world, unless those whose applause they seek have been made favorable to Christianity by its own intrinsic charms?

In order to estimate the power of the gospel over the mind of pagans, trained up in superstition, it may be proper to calculate the number of souls instrumentally converted from idolatry by a single minister of Christ, and then enquire how many proselytes a Hindoo Brahmin would collect in a Christian land, in the same term of time—let him exhibit the evidence of the authority of his god, and commend by its excellencies his system of worship. In is conceded that men have been dissuaded from that belief of Christianity which they had been taught from childhood, and led to denounce all religion; but this does not afford a fair experiment of the comparative strength of the Christian religion and infidelity, for in order to estimate the weight of evidence in favour of infidelity, we must ascertain and deduct the assistance it has derived from the passions. Let us suppose that a man in order to become a complete infidel, must publicly espouse his cause at the expense of house or land, or parental affection, or whatever else rises to hinder him in his profession—that he must devote a seventh part of his time to the promotion of his religion, and consecrate his substance to defray its expence—that he must not revenge an injury—when reviled he must bless—that he must pray to the author of his faith for blessings upon his persecutors, and weep over the miseries of those who are deluded by Christianity, and who then, from the power of conviction only, would become a conscientious infidel?

The perpetuity of the Christian religion in its primitive simplicity, amidst the changes of the world, is a further proof of the power of its Author.

The philosophy of Aristotle held dominion over the intellectual world about two hundred years, until its imperfections were detected by new discoveries made from time to time. Every new hypothesis triumphed over the opinions that preceded it; the fall of one system seemed essential to the rise of another. But with the Christian religion it is not so; it has remained essentially the same from its first establishment. Improvements it is true, have been suggested, and exertions used to adapt the doctrine and institutions of Christ to the change of circumstances; nor have these exertions been altogether without effect: but the true standard has not been prostrated; every revolving year has added thousands to the number who have contended earnestly for the faith once delivered to the saints. After all the corruptions which have tarnished the glory of the church, the simplicity of her doctrine still remains, and the spiritual arm of her Potentate is redeeming her captive sons. Upon present prospects we may safely rest our hope, that Jesus Christ will shortly manifest his sovereign power, and subdue all things to himself.

2d. From the sovereignty of Jesus Christ, we learn the responsibility of those who are entrusted with authority.

It is not intended to encumber the sacred office, by incorporating with it the task of inculcating maxims of civil policy; nor would we so far implicate the wisdom of our rulers, as to suppose them under the necessity of repairing to the house of God to learn a knowledge of jurisprudence; I would therefore, know nothing on this occasion, but Jesus Christ and him crucified. The subject before us however, suggests the propriety of preferring a memorial before this honorable body in behalf of the Christian religion, respectfully representing the influence of a public character over the habits of private life, and praying them by their personal example, to shed a lustre upon the morals of the community; and in their official capacity to maintain a wise reference to the tribunal of the only Potentate, before whose impartial throne the ruler is distinguished from his subjects only by his superior advantages improved, or by the more aggravated crimes which his exalted station has enabled him to commit. It is too generally forgotten, and sometimes denied, that the transactions of life are to pass a solemn review in the coming world; but it is to be hoped that men whose weight of character has entitled them to a place at the head of a Commonwealth, will bear in mind the intimate relation of human actions to a future state.

3d. The sovereignty of Jesus Christ secures advantage to the church, from all the changes and events which take place in the world.

Every revolution in the kingdoms of the world involves certain questions, the merits of which occupy the minds of statesmen, and regulate their hopes and fears. But the Christian looks beyond all these things, and beholds the exalted Saviour working all things after the counsel of his own will, and causing all things to work together for good to them that love God. Every public event opens an avenue for the rays of evangelical light. The cession of territory to the Russian empire at different times, has prepared the way for the spread of divine knowledge, and particularly for the spiritual instruction of the Jews.—The accession of the Earl of Minto to the government of Bengal, gave facilities to the missionaries of the cross, to propagate the gospel throughout India.—The public career of Bonaparte, though tracked in human blood, excited in many instances an enquiry after the true principles of religious liberty. What benefit may accrue to the Christian church from the late revolution in Europe, remains yet to be revealed by the order of Divine Providence; but should this event pass by, and contribute nothing to the general interests of the truth, it must be pronounced an EVENT EXTRAORDINARY in the annals of the world.

How consoling the reflection, that through the influence of Him who sits regent on the throne of universal dominion, the best effects may be realized from causes in themselves afflicting, and often unrighteous. Who that possesses human, (not to say Christian sympathy,) can look with cold indifference upon the distresses of a convulsed world, and contemplate without lamentation the fate of nations, dashing to pieces like a potter’s vessel? But the Christian, with the ye of faith, enlightened by the rays of Divine revelation, while he weeps over the destinies of the world, doomed and hastening to destruction, can rejoice in the expectation of a new heaven and a new earth, wherein dwelleth righteousness. Then let the wisdom of this world give place to the revelation of God.—Let wise men bring their offerings to the Babe of Bethlehem.—Let every human standard be prostrated at the foot of the cross.—Let every knee bow to the exalted Saviour, and let every tongue confess that Jesus is the Lord—of the increase of whose government and peace, there shall be no end. Amen.

Endnotes

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!