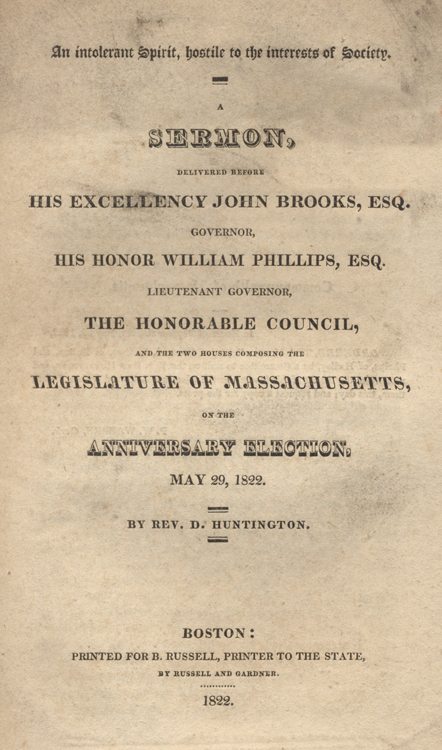

Daniel Huntington (1788-1858) graduated from Yale in 1807. He was pastor of a church in North Bridgewater, MA (1812-1832, 1841-1858). The following election sermon was preached by Huntington in Massachusetts on May 29, 1822.

A

SERMON,

DELIVERED BEFORE

HIS EXCELLENCY JOHN BROOKS, ESQ.

GOVERNOR,

HIS HONOR WILLIAM PHILLIPS, ESQ.

LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR,

THE HONORABLE COUNCIL,

AND THE TWO HOUSES COMPOSING THE

LEGISLATURE OF MASSACHUSETTS,

ON THE

ANNIVERSARY ELECTION,

MAY 29, 1822.

BY REV. D. HUNTINGTON.

ORDERED, That Messrs. Keyes, of Concord, Billings, of Boston, and Phelps, of Hadley, be a Committee to wait on the Rev. Dan Huntington, and return him the thanks of this House, for the Discourse delivered by him, before them, this day; and request a copy for the press.

Attest,

P. W. WARREN, Clerk.

“If it were a matter of wrong, or wicked lewdness, O ye Jews! Reason would that I should bear with you: But if it be a question of words, and names, and of your law, look ye to it; for I will be no judge of such matters.”

THESE are the words of Gallio, the deputy of Achaia, one of the old Grecian States, then a province of the Roman Empire. The Apostle Paul was now before him, in Corinth, the capital of the province, under an accusation brought against him by the Jews. He was charged with worshipping God contrary to the law. The charge was in connection with his having recently become a convert to the faith of the Gospel. From having been a proud persecuting Pharisee, he becomes an enlightened Christian. Commissioned from on high, he goes forth into the world, a preacher of righteousness. In the cities which he visits, to carry the glad tidings of the Gospel, he occasionally meets with the Jews, his “brethren and kinsmen, according to the flesh.” His conversion to Christianity, does not make him a stranger to them. He does not avoid their society, neither does he conceal his sentiments. Very frankly he expresses to them his convictions and his hopes. He appeals to his conduct, as the test of his sincerity. So far as they are disposed to accord to him the civilities of life, he accepts them. He takes up his residence with them: he labors with them, in his occupation: he goes with them “to the house of God in company,” occasionally addressing their assemblies, on the weighty subjects “pertaining to life and godliness.”

While he avails himself of their hospitality and their fellowship, however, he does not forfeit his independence as a man, nor does he forget his message as an Apostle. The theme of his preaching is “Jesus and the resurrection:” Jesus Christ, the Son of God; the hope of the sinner; in whom, as he often repeats, “we have redemption through his blood,” and the animating hope of “life everlasting.” His instructions “distil as the dew,” and drop as “the small rain upon the tender herb.” The desired effect is produced. Many of the Corinthians, both Jews and Greeks hearing, believe and are baptized. It is noticed by his former friends with a jealous alarm. Soon does he perceive among them, the consequences that too commonly follow disappointed ambition and wounded pride. Their indignation at length bursts forth, in acts of open violence. The banners of a religious warfare are unfurled. The usual engines of persecution are brought into operation. The Apostle is denounced. His name is cast out as evil. The doors of their synagogues are closed against him. The harshest epithets are applied. He is “a babler;” “a setter forth of strange God;” “a fellow that persuadeth men to worship God contrary to the law.” Wherever he goes, he is met by the Jews, “stirring up the people against him.”

Not having been convinced, however, by their arguments, nor duped by their flatteries, he is not now to be awed by their menaces. Alluding to their conduct, afterwards, in his epistle, to the inhabitants of this very city, he says, “Wherein soever any is bold, I am bold also. Hare they Hebrews? So am I. Are they Israelites? So am I. Are they the seed of Abraham? So am I. Are they ministers of Christ? I am more.” He ventures still to think for himself, and to teach as he believes.

Such being the nature of his crime, he is arraigned before the Proconsul of the province.

Gladly would he have availed himself of such an opportunity, at once for attesting to his innocence of the charge brought against him; and for exhibiting to those around him, as he had before done, in similar instances, the consolations of the religion of Christ.

But when now about to open his mouth, Gallio said unto the Jews, “If it were a matter of wrong, or wicked lewdness, O ye Jews, reason would that I should bear with you: but if it be a question of words, and of names, and of your law, look ye to it, for I will be no judge of such matters. And he drave them from the judgment seat.”

The story is instructive, showing us that there is a disposition in men, to control the opinions of their fellow men:

The means used to accomplish the object:

And that such a disposition, wherever it exists, is not only hateful in itself, but hostile to the interests of social happiness.

It deserves attention, as one of the opening acts of a scene, in which, for ages, the human character has been unfolding, in events disastrous to society beyond description, and which, we trust in God, is now drawing to a close. Happy shall I think myself, if anything may be said on this occasion, to hasten a consummation so desirable.

The subject shows us,

I. That there is a disposition among men, to control the opinions of their fellow men; especially their religious opinions.

The disposition often originates in a restless desire for power. To be able to dictate without contradiction, gives an ascendancy, always congenial to the feelings of the aspiring partisan.

The origin of this disposition, however, need not always be resolved into depravity of character. We often perceive its commencement, in some of the best feelings of our nature. Honestly believing our own opinions, on important subjects, to be right, the wish that others may embrace them, is not only innocent, it is kind, and commendable. Regarding our principles, as the rule of conduct, and the basis of character, we cannot be too much in earnest, to have them established in our own minds, and in endeavoring by fair means, so to recommend them to those within the circle of our influence, as to persuade them to see, and feel, and act with us.

But how few, comparatively, have appeared to be satisfied with this! How many, not content with being right themselves; and with the best arguments they can use to influence others; making their own speculations the standard of truth and duty—are too ready to insist, that all around shall conform to it! A want of conformity, is in their estimation, a proof of their error. If the question in agitation, be of a religious nature, they are fatally wrong. Religion, from its native importance, heightening as it does, every passion on which it acts; and rendering every contest into which it enters, uncommonly ardent—their principles, their motives, and their characters, are condemned by those who differ from them, with unfeeling severity.

Being thus deep rooted, in the very principle of our natures, we must expect to find the development of this spirit, in every period of the world. And do we not find it, in fact, coeval with the history of man? For nearly six thousand years, has it not been producing its baleful effects among the nations?

Confining our attention, however, to what has taken place, since the introduction of Christianity, how has its mischievous power here displayed itself in all its atrocity! It was visible, even in the family of our Saviour. It was one of his own disciples who said, “Master, we saw one casting out devils in thy name, and we forbade him, because he followeth not with us.” More than once, had our Lord occasion to reprove this spirit, in those around him.

Constantly, were both he and his disciples, harassed by the Scribes and Pharisees, on account of the doctrines which they taught. Of him the complaint was “He deceiveth the people.” And with respect to the disciples, the imposing interrogatory was, “Why do they transgress the tradition of the elders.”

And what was the result? Said our Saviour, “The disciple is not above his master, nor the servant above his Lord. Beware of men, for they will deliver you up to the councils, and they will scourge you in their synagogues. If they have persecuted me, they will also persecute you.” This is now history. He himself soon fell a victim to their intolerance; and his disciples, in every succeeding period of the church, have, in a greater or less degree, been drinking the same bitter cup.

Innumerable, almost, are the examples of this spirit, both in the conduct of Jews and Pagans toward the primitive Christians; in the conduct of Christians among themselves; and in their conduct toward the heathen, whom by violence, they undertook to proselyte to Christianity. Under its infatuating influence, the persecuted, for conscience sake, have become persecutors; and these, in their turn, have suffered the evils they had inflicted on others.

The subject leads us

II. To consider the means which have been used by those who have undertaken thus to control the opinions of others. The means employed on this occasion, were violence and fraud. We have already seen the Apostle before the Roman governor, both falsely accused, and grossly insulted—and had the clamors of his persecutors prevailed, probably the loss of life, would have been the immediate consequence of an adherence to his opinions. Where the state of society has favored it, something similar to this, has been the usual process for making free inquiry hazardous.

The first step has been, to produce an impression of infallibility, in the person, or the body, assuming the controlling power. They must be resorted to, as the unerring oracle. Claiming the keys of the kingdom, the door to its immunities must be opened or closed by them; and their decisions must be received with the most unwavering confidence.

Implicit faith, on the part of those to be controlled, is no less necessary, in establishing the desired ascendency, than infallibility in those who assume the power of controlling. The common people, as if incapable of understanding the word of God, must resign themselves to their teachers. As if blind, they must be led. When led, they must not hesitate to follow. Their reason, their judgment, their conscience, their moral agency; their interests for time and eternity, are no longer at their own disposal. And to have it known that they are not, frequent experiments must be made upon their credulity and good nature. If they hear it inculcated with uncommon ardor, that a few speculative points in theology, are the essentials of religion, no doubts may be entertained. If taught that “all error is fatal,” they must believe it. They must often, be made to understand, that all the remaining piety on the earth, has taken up its last abode with the people of their denomination; and that to them it belongs exclusively, to preserve and perpetuate sound doctrine and a pure church. It has been found, at some periods, and among some classes of Christians, not too great a stretch of credulity, for the proper exercise of implicit faith, to believe that dishonesty, falsehood, calumny, cruelty oppression, and wickedness of almost any description is venial, if in practicing it, what is called a good object may be promoted.

Other notions, similar to this in their spirit and tendency, such as that the correctness of opinions, is to be estimated according to their antiquity and prevalence; and that it is reproachful for a person to change his opinions—have been equally current. Where these expedients have failed of producing their desired effect, others have not been wanting.

The last resort of the persecuting bigot has been, to compel men to believe right. Aided by mystery, creeds, canons, decrees and councils, with all their appropriate appendages of terror, he commences the dreadful work. If they are few in number, who dissent from the common faith, he avails himself of the vantage-ground afforded him from this circumstance, for exciting, if possible, a general prejudice against them. This is done, by identifying them with everything odious; by indiscriminate censure; by vague and unfounded charges often repeated; by ungenerous allusions; unjust insinuations; unfair reasonings; and terrific denunciations. To these have succeeded, vexations ecclesiastical processes, beginning in making men offenders for a word, and issuing in the highest acts of discipline. Where the times have been favorable, in how many instances has death, in all its dreadful forms, been the consequence of a conscientious adherence to truth!

The object under the

III. General head of this discourse, is to show that the disposition manifested in these efforts to prevent free inquiry, is not only hateful in itself, but hostile in its effects, to the interests of social happiness.

Its effect, at Corinth, was an insurrection. The disturbance arose, as we have seen, from the exclusive spirit of the Jews, in their attempts to silence the Apostle.

The most violent dissentions, and the most bloody wars have arisen among men, in attempting by authority to regulate each others opinions.

Much has been said on the subject of heresy, and much has been done to suppress it. But it is worthy of remark, that all the mischief in society, has arisen rather from opposition to heresy, than from heresy itself.

The Apostle was now successfully preaching the gospel; and both he and his converts were walking worthy their vocation as Christians. But the Jews and others were continually dissatisfied. Their craft was in danger. Their pride of opinion, their prejudices, their interests were affected by his success. He had his adherents, and they had theirs. Hence the tumult.

Like causes, producing like effects, we must always expect the exclusive and controlling spirit, to produce disorder.

It is a gross insult offered to the understandings of men. The language of it is, either you have not the necessary faculties to comprehend what you are taught from the sacred oracles, or you have not integrity to avow what you really believe. A charge, founded upon either alternative, is touching a man of common feelings, where his sensibility cannot fail to be excited; and brings into action those passions, which are always unfavourable to social intercourse.

It is also a violation of right: and whenever the rights of men, and especially their religious rights, are invaded, there will be a reaction. The peace of society will be disturbed.

Let none infer, fr5om what may be said in contending for freedom of inquiry, that it is supposed to be of no importance, what a man believes. Our sentiments are our principles of action. Good sentiments, legitimately derived from the word of God, are unquestionably the foundation of religion. But in determining what these are, every man must judge for himself.—“Why even of yourselves,” saith our Lord, “judge ye not what is right.” “Not for that we have dominion over your faith,” saith our Apostle. And again, “Who art thou, that judgest another man’s servant.” Every man must judge for himself, and any attempt to subject him to any inconvenience on this account, is usurpation. It is an invasion of an unalienable right. Any man, or body of men, attempting to deprive me of that right encroaches upon Christian liberty, and is to be resisted. “If the foundations be destroyed, what can the righteous do.” The first principles of religious freedom being invaded, what security have we, for anything valuable.

Of the evils of persecution, nothing need be added. Its name is legion. Wherever the persecuting spirit has had power, it has been destructive beyond description. In resisting its impious claims, what torrents of blood have flowed; what privations and pains; what afflictions, in a thousand forms, have been endured!

It may, however, and often does exist, where the civil arm is wanting. There is a persecuting heart, and a persecuting tongue, as well as a persecuting sword. Hard names, uncharitable censures, rash dealings, are the very essence of it. Public slander, bitter reviling, “babblings,” “wounds without cause,” are as inconsistent with the spirit of the gospel, as to banish, imprison, and destroy men for their religion. With such a spirit walking about like “a roaring lion, seeking whom it may devour,” what have society before them but contention and woe?

The demoralizing effects of certain popular sentiments, which have sometimes obtained currency, must be evident to all.

That the end sanctifies the means, though too gross to be avowed, it cannot be denied, has had a secret and most pernicious influence.

Nor is it less evident, that the reproach so often cast upon men, for changing their opinions, is unfriendly to the progress of truth, and of course to human happiness.

To be “carried about by every wind of doctrine;” to change our opinions from mere whim and caprice, is certainly a disgrace and a sin.

But it is not less degrading and sinful, for a man, from the same motives, to defend opinions contrary to his convictions.

Implicitly to receive for truth, the speculations of those who have gone before us, is indeed, an effectual bar to all improvement. Said the venerable Robinson, in his well known parting advice, to that part of his flock who have been styled the pilgrims of New England, “I cannot sufficiently bewail the condition of the reformed churches, who are come to a period in religion, and will go, at present, no further than the instruments of their reformation.”

The notion, also, that the correctness of opinions is to be estimated according to their prevalence, is equally calculated to mislead mankind.

There was a time, during the Jewish monarchy, when a popular leader seduced the affections of the body of the people, placed himself at the head of ten tribes, and drew them off from the worship of the true God, to the idols, set up in Bethel and Dan.

Was it the duty of the two remaining tribes, to follow the example of the ten? Had they done it, and had they left upon record for it, that they thought it not justifiable to oppose the majority, would it have been evidence that they were a wise and virtuous people?

When there were only seven thousand in Israel, who had not bowed the knee to Baal, among the hundreds of thousands, who had, did they wisely, or did they not, in opposing the multitude?

When the darkness of superstition and idolatry overspread the face of the Christian Church, what would have become of pure religion, had not the Albigenses, and the Waldenses, and a few others, retired to the mountains of Italy, that they might there enjoy, unmolested, the blessed truths of an uncorrupted gospel.

If Wickliffe, Luther, Melanethon, and a few others, the fathers of the reformation, had not dared to make themselves singular in contending for Christian liberty, we might still have been groping in the darkness, and groaning under the burden of a most blind and cruel superstition.

We are never at liberty to “follow a multitude to do evil.” To be singular in a good cause, is proof of superior virtue. And to all who have their rials on this subject, it is said, “be thou faithful unto death, and I will give thee a crown of life;” while of those, who by their numbers, are embolden to harden themselves in transgression, it is said, “though hand join in hand,” they “shall not be unpunished.”

We have now attended to several thoughts suggested by the subject. We have seen from it, that the disposition in men, to control, by authority, the opinions of their fellow men, which has always been a dominant passion in the human breast, has been productive of an immense mischief to society. And it is because of its deleterious influence upon society and social happiness, that it has been made a topic for the present occasion. To this view of the subject, I have endeavoured, and shall still endeavour to confine myself.

It only remains to inquire, is it applicable to us?—and if so, how shall the evil complained of be remedied?

Does the subject then admit of an application to our own community?

Let the intelligent look at what is passing in many of our Congregations and Churches; in Ecclesiastical Associations and Councils, and answer for themselves. Let them listen to the voice of clamor and contumely, of terror and exclusion, issuing from the pulpit and the press, and echoing from one extremity of our limits to another, impeaching the purest motives, maligning the fairest characters, and enkindling unjust suspicions among the uninformed.—Let them observe the movements of those who set themselves in opposition to every gentle and tolerating measure; let them notice the projects that are put in operation for enlisting partisans, and for augmenting their resources. To gain the control of funds, see them, not only fawning upon the widow, and those who are so unhappy as to be destitute of near relatives, but watching around the dying pillow of the opulent, crying like the horse leach, “give, give;” encouraging the belief, that every cent committed to their disposal, shall be a gem in that crown of glory finally to be bestowed as a reward to the fidelity of their votaries.

Who that has read the history of Ignatius Loyola, and his followers; of their objects; of the peculiarities of their policy and government; of the progress of their power and influence, and of the pernicious effect of this order on civil society, that does not sometimes feel the mingled emotions of grief and indignation, at what he still sees passing before him?

Guarded, however, as the cause of religious liberty, at the present day is, by Genius, Literature and Religion, under the government of a holy God, she has nothing to fear. It ought to be mentioned with gratitude, to the great Author of all good, that we live in a day, when the principles of civil and religious liberty are so well understood. Many are disposed to open their eyes to the light of truth, and are roused to act. The reign of terror is past. The Inquisition is no longer in force. The thunders of the Vatican have ceased to roar. The dogmas of the school-men are no longer in vogue. The Gibbet is not now to be seen planted before our doors. The fires of persecution no longer blaze around our dwellings. Our sanctuaries of justice are unpolluted. Our rulers are enlightened, and the people are free.

It daily becomes more and more evident, that an imposing spirit, as it is not suited to the genius of a free people, cannot long be sustained by them. In very respectable portions of the community, it has been tried, and is well understood, that men will not be controlled in their opinions.

But still “the yoke of every oppressor” is not broken. There are burdens and impositions, which are still felt. If the power is taken away, the disposition to prevent free inquiry by authority is not wanting. It is not to be disguised, that in some sections of this enlightened Christian community, there is too much evidence of a disposition for spiritual domination, which is producing in society a perpetual mischief. There are bodies of men, still claiming a jurisdiction as absolute, if not as extensive, as was ever claimed by the most imposing Pontiffs of the dark ages.

It is what some constantly see, and hear, and feel. We are daily conversant with those, the language of whose conduct is, “Stand by thyself, I am holier than thou:” and who, considering themselves “to have attained,” in every necessary qualification, gratuitously assume the prerogative, of dictating to their fellow Christians, on disputed points, what they shall believe. With no superior claims to the necessary means of enlightening their fellow men; having had no more than common advantages for information: having no credentials of any special illumination: from their lives appearing to be, certainly, as much uninspired men as others: and differing as much from one another, as from those, whom they unite in condemning – they seem to be constantly saying to those around then, “The secret of the Lord is with us,” “hear his word at our mouths.” And if any, after this, in exercising the right of private judgment, fall into “the way that some call heresy,” the harshest epithets are applied. They are denounced, as introducing “another Gospel”; as “Apostates”; as “Deists in disguise.” If moral, they are accused of making a merit of their morality. If pious, it is hypocrisy.

In all these means, which are used for controlling the right of private judgment, do we not perceive the shattered remnants of the machinery of a once formidable and most mischievous hierarchy? And shall we see our fellow men collecting and arranging these remnants; and endeavoring again to bring them into action, without letting them know, that we are not insensible to their operations, and the evils of them.

Can we reflect that the subject admits of a direct and unequivocal application to ourselves; that the evils complained of do exist; and sink down under it, into a state of total unconcernedness? Realizing that the blessings of Independence are our birthright: being inhabitants of the Commonwealth, whose Constitution was the first to acknowledge the great principles of civil and religious liberty: living as we do, where those principles have ever been well understood and firmly maintained: occupying the ground where those struggles commenced, which issued in the freedom of our country: surrounded as we still are, by those who bore a conspicuous part in those struggles: in view, too, of those blood-stained heights, where the friends of freedom first met the shock of battle, and where now repose the ashes of the virtuous brave: surrounding, also, these altars, where, in the days of our fathers, the prayers of many a wrestling Jacob, in favor of the same cause, have ascended to the throne of God, and have prevailed; offering our devotions, as we do, at the present hour, among a people, who have not only prayed, but have lived like Christians; where the ministers of religion and the people of their respective charges, have, for the most part, like the primitive disciples maintained a delightful and harmonious intercourse;–can we contemplate with cold indifference, a spirit, which is at work, not only to dissolve this harmony where it exists, but which is calculated, also, to exert a most destructive influence throughout all our Towns and Churches?

Apprized of the evil, we inquire, How may it be remedied? As we would be a happy people, every encroachment upon Christian liberty, must be resisted. The resistance, where there is occasion for it, should be mild, courteous and dignified; at the same time, it should be frank and determined. It should be made, under a deep and solemn impression, that all other privileges are comparatively trifling, unless we can, unbiased and unembarrassed, continue to open our eyes upon the light of divine truth as it is communicated to us.

But why do I speak of resistance? Rather let all endeavor that any occasion for it may be unnecessary.

In order to this, be it understood, that the great questions, which, at the present day, agitate the public mind, are not to be decided by the force of authority. Men must be left, undisturbed, to enjoy the fruits of their own inquiries, and to decide for themselves. In forming our opinions, there must be mutual condescension. What we claim for ourselves, we must willingly concede to others. This must be done with good feelings; in the exercise of kind affections; in the spirit of humility; remembering that those who differ from us, no less than ourselves, have interests of infinite moment at stake.

Let it be understood, also, that with the same upright motives, in their investigations, men will arrive at extremely different results; that the members of the body of Christ, of all denominations, do “drink into the same spirit.” Guided by the word of God, and endeavoring to regulate their lives by its rules, they are aiming at the same thing. The honor of God; the peace and prosperity of society; their own salvation, and the salvation of those around them, is what they are all seeking. Let every man have the credit of good intentions, so far as it is supported by fair and honorable conduct. In addition to this, let the means of information continue to be generally diffused, and be made easy of access.

A principal artifice of the superstition of former ages, has been to keep the common people in ignorance: and in the true spirit of such a procedure, we still hear them advised, with the appearance of great seriousness, “not to read the writings, nor be present at the instructions,” of those, who in giving their own opinions of revealed truth, dissent from the common faith.

But is there any other way of dealing honestly with a rational being, at liberty to inquire for the truth, than to give him the advantages for knowing it, and leave him to judge for himself. The influence of such a course, has been tested: its good effects are visible: let it be still pursued, and we may hope, that error will vanish like the mist of the morning, before the rising sun.

If any with whom we are conversant, appear to be mistaken in their views of religion, let us endeavor to instruct them; if ignorant, let us enlighten them; if censorious, insolent, and dogmatical, in the spirit of meekness and love, let us rebuke them; but by no means, let us take upon ourselves the awfully hazardous responsibility of determining their future destiny. “Judge not, that ye be not judged.”

Would we see unhappy divisions multiplied: friendly intercourse interrupted: and the charities of life destroyed, then let us indulge an exclusive spirit: go on to draw dividing lines: to erect separate interests: to form parties and combinations to hunt down and devour one another.

On the other hand, would we enjoy true happiness, so far as it can be enjoyed in the present state; then in addition to our other innumerable blessings, “Let us seek the things that make for peace, and things wherewith one may edify another.” Believing as we are taught, that he who is not against Christ, is on his part, let us aspire to an elevation of sentiment, and a generosity of soul, which will enable us to look beyond all petty distinctions of party and system; and which will lead us in making our estimate of men, to look principally at their life and conversation. “By their fruits shall ye know them.”

All have an interest in the subject. It has been selected for the occasion, under the impression, perhaps a mistaken one, that it calls for public notice. It has been freely discussed, with the conviction, that the great principles of the Reformation, from which society has derived such a rich harvest of blessings, should ever be cherished in grateful remembrance: that every encroachment upon them should be regarded with a jealous eye: and that open opposition should with a jealous eye: and that open opposition should, if possible, be awed into silence. So important a cause, hitherto so happily maintained, we trust will never be abandoned.

We cannot but felicitate ourselves and the public, in view of the progress of Christian light and liberty, not only in our own State; but in our common country, and through the civilized world. Of this there are evident tokens. We rejoice to believe, that the time is advancing, when Christianity, unencumbered with those errors and corruptions which have been heaped upon it for ages, and no longer haunted by the demon of persecution, will everywhere prevail, and will be found in all the relations of life, to have its peculiar effects.

The subject, we trust, will be suitably noticed by our political fathers, to whom we look with confidence, in all our concerns, connected with the public peace and prosperity. To them we look, on this occasion, not for legislative interference, but for their influence as men and as Christians, who always have at heart the high interests of the State.

To determine “questions of words and names,” and ceremonies, which have been too much the subject of angry dispute and bloody contest, the enlightened Christian Magistrate will not consider a duty of his office.

In questions of conscience merely, though he may have an opinion of his own, he will not feel himself at liberty to decide for others.

And above all, will he be on his guard against lending his aid to persecutors. The conduct of the Roman Governor, in this respect, will meet the approbation of every judicious man. So far did he well, in caring for none of those things—So far, is his example worthy of imitation.

In other respects, however, his conduct is altogether the reverse of what we should expect in a wise and virtuous Magistrate. With the credentials, which the Apostle offered, Gallio was inexcusable, for not hearing him with respectful attention, and for not listening to his defense. Clothed in the pride of office, he seems not only to have been regardless of the interests of religion, but seems not to have cared, whether the accused suffered justly or unjustly.

His conduct was unbecoming a good ruler, in refusing protection, at the same time, to Sorsthenes, and, and in neglecting to quell the tumult which arose on his account.

The members of every well regulated society, have a decided interest in its welfare. The man of generous feelings, will never stand the unconcerned spectator of suffering innocence; and if clothed with authority, as he will not see the rights of conscience invaded without rebuke, so will he not suffer disorder and excess to go unpunished. In every situation, as the bold reprove of vice, he will be “a terror to evil doers, and for the praise of them, that do well.” “He that ruleth over men must be just, ruling in the fear of God.” He will not forget, but with Gallio will remember, that “matters of wrong and wicked lewdness”—injustice and licentiousness, vice and immorality, are the subjects which peculiarly belong to his province; and that to restrain and suppress them, is the great object for which he is elevated to power. In dispelling the clouds that may have been gathered by ignorance, and prejudice and sin, his influence will be “as the light of the morning when the sun ariseth: even a morning without clouds; as the tender grass springing out of the earth by clear shining after rain.”

He will cultivate that peace in his own breast, which in some measure composes the turbulent passions. In private life, he will be an example of the virtues of the Gospel. His public administrations will be marked with that true dignity of character, in which, honor, integrity, wisdom, disinterestedness, benevolence, and genuine patriotism, are harmoniously blended.

We look to him as the guardian of our rights, civil and religious. In every situation, in short, we expect to find in him, and exemplification of “the wisdom, which is from above; which is first pure, then peaceable, gentle, and easy to be entreated, full of mercy and good fruits, without partiality, and without hypocrisy.”

With such rulers, have the inhabitants of this Commonwealth, been richly blessed, for successive generations.

Assembled on this joyful anniversary, we offer them the congratulations of the occasion. We tender them the homage of our respects. We hail them as the friends of our liberties, and of social order. We implore, in their behalf, the choicest benediction, of the Supreme Ruler.

In their deliberations and decisions, may they have the divine guidance—And in the great day of final decision may it appear, that in our respective stations, we have so discharged all relative and social duties, that in the abundant mercy of God, manifested through our Lord Jesus Christ, our works may follow us to a blessed reward.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!