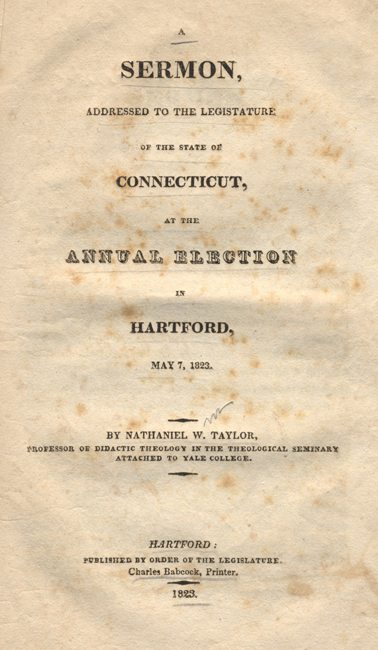

Nathaniel Taylor (1786-1858) graduated from Yale in 1807. He was pastor of the First Congregational church of New Haven from 1812 until 1822, when he was appointed Professor of Didactic Theology at Yale. This election sermon was preached by Rev. Taylor in Hartford, CT on May 7, 1823.

SERMON,

ADDRESSED TO THE LEGISLATURE

OF THE STATE OF

CONNECTICUT,

AT THE

ANNUAL ELECTION

IN

HARTFORD,

MAY 7, 1823.

BY NATHANIEL W. TAYLOR,

PROFESSOR OF DIDACTIC THEOLOGY IN THE THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY

ATTACHED TO YALE COLLEGE.

HARTFORD:

PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE LEGISLATURE.

Charles Babcock, Printer.

1823.

At a General Assembly of the State of Connecticut, holden at Hartford, in said State, on the first Wednesday of May, A. D. 1823.

RESOLVED BY THIS ASSEMBLY, That the Hon. William Moseley and Cornelius Tuthill, Esq. be a Committee to present the thanks of this Assembly to the Rev. NATHANIEL W. TAYLOR, for the Sermon delivered by him before the Assembly, at the opening of the Session, and to request a copy thereof, that it may be printed.

Examined by

THOMAS DAY, Secretary.

“And judgment is turned away backward, and justice standeth afar off; for

Truth is fallen in the street, and equity cannot enter.”

WITH the exception of a few political visionaries, the world has concurred in the opinion, that mankind must be governed. Man finds so many opportunities and inducements to injure others for his own benefit, he is so destitute of any principle within him to rise up for their defence, that if there were no influence from without, to overawe him into a respect for their rights, like a beast of prey, he would be ever ready to destroy.

Conspicuous as are the wisdom and goodness of God in upholding human society, without the prevalence of the benevolent affections, even his mercy has provided no relief from the ravages of overt injustice. The moment that mutual injury begins, the moment that mutual animosity controls the social intercourse of a community, all its bands are broken. Even a company of highwaymen must abstain from robbing and murdering one another, or abandon their association. Justice then, as opposed to overt acts of injustice, is the main pillar of human society. Take this away and the whole edifice crumbles into ruins.

Hence the grand object for which civil government is required, and at which it aims, is to enforce the observance of justice.

The text refers us to a period in the history of Israel, when this great design of civil government was wholly defeated. A total disregard of the rights of men, distrust and violence prevailed in their most appalling forms, and were felt in their most dreadful results. Of these calamities the text also assigns the cause: “For truth is fallen in the street—and equity cannot enter.” Truth, as it unfolds the rules and motives of moral action, was contemned and disregarded throughout the community. The sense of an ever-present Ruler and Judge, the restraints of laws enforced by sanctions drawn from eternity, had lost their power on the consciences and conduct of men. Of such a prostration of the standard of public morals, the consequence was natural. There was a disruption of social ties, and a lawless spirit, that let loose human selfishness to invade human peace and happiness, without check and without relief.

The text then will lead me to shew, that a corrupt public opinion, on the subject of morals, destroys the efficacy of civil government.

This will appear, if we consider

1. The inherent weakness of civil government—The efficacy of civil government, to secure the observance of its laws, must consist wholly in its rightful authority, and in its penal sanctions.

All authority in civil government must be founded in the right of the Ruler to claim the obedience of subjects; and all the influence of such authority must result from an acknowledged obligation on the part of the subject to submit to its demands. But a corrupt public opinion disclaims such obligation; and of course the validity of every claim for obedience on the ground of rightful authority. Shall the subject be told that protection and obedience are reciprocal duties? Shall he be told that he has entered into the social compact, and by virtual stipulation relinquished his natural right into the hands of the ruling power? Shall he be told of the public good and of the anarchy and the woes which result from trampling on the laws of the land? But what are duties, compacts, the public good, or the public ruin, to the man who disclaims all moral obligation? Civil laws, in such a case, are mere appeals to human selfishness in one form, to repress human selfishness in another, leaving man accountable simply to himself. The rightful authority of the Ruler, as “a minister of God for good,” being disclaimed, every man’s inclination is his law, his tribunal, and his judge.

Nor is the fact changed by the influence of penal sanctions. To man, viewed simply in relation to laws enforced by civil penalties, this world is the only place of retribution; and every question of obedience or disobedience is with him merely an arithmetical problem respecting the amount of his present personal advantage. Aside then from the success which attends the active invention and unwearied artifices of those who devise and pursue their own interest in defiance of human laws; aside from the confidence with which crime relies on concealment or escape; there is often an energy in human passion, which penalties, threatened by human power, cannot restrain. Bodily suffering is of light estimation, compared with the restlessness or anguish of ungratified desire. The death-song of the savage, which he sings when expiring under the hands of his tormentors, shows how the spirit within can sustain the pressure from without. But the spirit, tortured by its own fires, awakes to desperation. Obstruct the path of excited avarice or excited ambition, by toil, by suffering or even by torment, and the influence to check its career is as stubble before the spreading flame. Let then a corrupt public opinion detach from civil government its moral obligation, and leave it only the influence of penal sanctions, and let the prospect of wealth or fame open bright to their appropriate passions, and the deeds of the pirate and the hero tell us what men would do. How would terror and consternation seize every heart in a moment, did we know that there was nothing but the feeble arm of magistracy to protect us from the daggers of assassins.

2. The truth of our position is apparent from the direct influence of public opinion on civil government. Public opinion, in fact, governs the world. Its influence in elective governments, where all authority returns back into the hands of the people at frequent intervals, is absolutely paramount to every other.—That which forms the laws, is the opinion of the people, expressed by the voice of the people. It is through this influence that governments, and their specific regulations, are modified or wholly abandoned by revolution and change. That, on which the administration of a government depends, is the opinion of the people, expressed by the voice of the people. So much so, that any exceptions, to the decisive control of this authority, is a sure preliminary to changes that shall restore its supremacy. That, which determines the execution of the laws, is the opinion of the people expressed by the voice of the people; so much so, that a law which carries not with it the sanction of its own popularity, becomes extinct by repeal, or obsolete by desuetude. What then is civil government, with its laws and their sanctions, before the controlling power of public opinion? What are legislators, what are judges, what are executive officers? The mere vehicles of expressing public opinion; the instruments of the will of the people; the v0x populi forming its edicts and its laws, and carrying them into execution. Nor is this any perversion of republican institutions. It shows, however, the controlling principle of the whole machinery, the presiding genius of our whole political system. This, I say, is public opinion, and it should be so; it is essential to the very existence of that form of government which, under God, has so long blessed us. Still it is a fact, and a fact which may serve to show us where our strength lies, and whence, if at all, weakness and ruin will overtake us. Let public opinion, with all this omnipotence of control, become deeply corrupt, and still government, its laws, their framers, their executors, are all subservient to its dictates. What do laws against murder avail, under the frown of public opinion? Let the laws against dueling, in many parts of our own country, answer. What are laws against bodily torture, when the practice of it is countenanced by public opinion? Barbarities, which are enough to make our blood curdle, inflicted on many unhappy victims of slavery, furnish the answer. What are laws against drunkenness, when the popular voice forbids their execution? The woes and the groans of the land bring the reply to every ear. Now let public opinion advance in degeneracy, till it shall decree into its public enactments, the maxims of infidelity and atheism; let the living God be voted out of existence, and death, the door of eternal retribution, be transformed into the unbroken sleep of the grave; let evil be called good and good evil, darkness be put for light and light for darkness; and what would be your legislators, your judges, your witnesses, your executive officers? The mere panders and patrons of crime. What would be your subjects?—The mere perpetrators of crime. And how long before a tide of woes would overwhelm all that is fair and happy in the land? How long before an impatience under miseries, which humanity could not endure, would madden and convulse the nation, till every foundation of order, peace and happiness, would be subverted as by the shock of an earthquake.

3. A corrupt public opinion destroys all that subsidiary influence, on which the efficacy of civil laws chiefly depends. It is a fact, which admits of no denial, that not the love of God, not the disinterested love of our species, but selfishness, is the governing principle of the great bulk of mankind.

When we reflect on this fact, on the countless temptations to selfish gratification, and the facilities of attaining it by deceit and violence, and when at the same time, we look over the face of society, and witness the security with which man counts on his enjoyments, it is truly a cause of astonishment to see on what all this security depends. Human laws do indeed put their restraints on many crimes; they do promote many of the practical moralities of life; and thus exert an influence, without which, every vestige of social good would be swept away. But then how entirely dependent are these laws for their results on an influence not their own? How innumerable are the actions of men, over which they can exert no more influence, than we can extend to the elements of future storms when preparing for their desolations?

It is precisely in these circumstances that a sound public opinion holds a check on human selfishness, for which we might look in vain to the combined strength of nations. This it does, through the medium of custom and fashion, of a regard to moral character, and of conscience and the fear of God.

There is perhaps no kind of moral action to which custom and fashion cannot reconcile man, or which they cannot render even agreeable. Their power to divest bestiality itself of its offensiveness, and crime of its enormity, may be learned in the politest city of Europe. It is this influence which, even in this country, tolerates slavery with its tortures and its murders, among those who in other respects are humane and liberal. It is this which sustains in vogue, the honorable way of killing by single combat, and which often gives sanction and currency to practices in one age, which it interdicts with the deepest frown of abhorrence in another. In short, what custom and fashion require or justify is the way of the world; and they will retain the great mass of a community in the path which they prescribe, though it be the path of death.—In vain then is the voice of legislation lifted against the voice of fashion. What the latter demands or patronizes will infallibly compel legislative submission or legislative connivance.

Now it is public opinion which imparts this high and commanding supremacy to custom and fashion, and thus creates and sustains a standard of moral action which sets legislative power at defiance. Let then public opinion, through this medium, I do not say sanction the violation of civil statutes, but give currency merely to those vices, and proscribe merely those moralities which no human laws can reach; let all that strictness of morals, that regularity of conduct, and those proprieties and decencies of deportment, which prevail in a well ordered family, neighborhood, or larger community, become repulsively unfashionable; and how soon would distrust and suspicion sunder every tie of social life, and human selfishness awake in the forms of malice, revenge and cruelty, and be witnessed in all the horrors of its fierce and relentless struggles!

Another influence of public opinion, indispensable to the efficacy of civil laws, is a regard to moral character. Pride of character is the master passion of an unsanctified world. No man can endure the misery of being despised by all around him, with the consciousness that he deserves it. When he can no longer look society in the face, and when he feels himself to be case out of affection and fellowship with all, he retires to a solitude of still deeper wretchedness. There he feels those inward pangs from which no secrecy can protect, under which no hardihood of soul can sustain him; and which, like avenging furies, haunt his guilty spirit and drive him to desperation or distraction.

Here then is a mighty influence of counteraction on human selfishness; an influence to which, in this world, society owes most of its tranquility and enjoyment; an influence so powerful on the one hand, that were the standard of moral character to be raised so high, and to become so imperious in a community, s to banish every enemy of its peace into an exile of self-contempt, a solitude where he should be greeted neither by human sympathy, nor human affection, civil laws would be superseded, or required only as rules of counsel and direction; an influence so powerful on the other hand, that obedience to civil statutes which should involve in disgrace and infamy, no weight of penalty could enforce, for torment and death would be more welcome than the retribution of such obedience.

Now this regard to reputation, with all its power of control, is not so much the desire of meriting, as of actually obtaining public approbation. It makes all wish to be accounted fit for society; in none does it awaken the purpose of being really fit. It therefore secures simply that degree of moral virtue, and of exemption from crime, which constitute such fitness in the judgment of those who arbitrate the question. Of course in man, as a member of civil society, it is a desire and an aim exactly graduated by the standard of moral character which public opinion erects. Beyond the limit which public opinion prescribes as honorable, human selfishness will not go, in obedience to legislative requirement; within this limit it will advance to its object, regardless of legislative prohibition though its way be tracked with blood.

In vain then do we look to human laws, deriving no support from public opinion, to curb the fury of human passions. Let this single influence be unfelt, let public opinion cease to attach infamy to crime, and award only shame and contempt to the sanctity of virtue, let there be none anxious to maintain nor willing to make a single sacrifice to maintain an average moral character, and how common would licentious and barbarous deeds become? How would the quiet of mutual confidence be displaced by the excesses and alarms of unbridled ferocity? Human selfishness would become its own lawless avenger in the retaliation of wrongs, in violence and in massacre; and we should go into an assemblage of men as we should enter a den of lions.

Public opinion acts no less powerfully in securing to human laws their efficacy, through the medium of conscience and the fear of God. He who formed and protects us has provided, within our own bosoms, a check for that injustice which is beyond the restraining power of man. There is a voice within which gives to moral sanctions an efficacy more powerful than that of a thousand gibbets. In the presence of conscience, man is in the presence of God; and the same voice speaks to him, which speaks to angels and to arch-angels from the throne of the eternal. Through the same medium, rewards and punishments adjudged by omnipotence and operating at tall times and in all circumstances, bring their palpable and pressing power to bear on moral action. I need not say how entirely all this influence on the great mass of the community depends on the soundness of public opinion. It is public opinion, as it upholds the standard of duty and obligation, which gives to conscience all its power. Thus it exhibits the moral turpitude of crime to steady inspection, and by anticipation constrains the criminal to read in every eye that meets him, the reproach that echoes in his own heart. Were the light of moral truth, then, to be extinguished from the public mind; were a corrupt public opinion to dispense with the moral and religious instruction of children, with the institution of the Sabbath, with the revelation which God has made of himself, of his law, and of human destiny, with all the appointed vehicles of conveying moral truth to the mind; conscience would become extinct in the soul of man. And what, then, would be the power of human edicts? Let there be none sensible to the high and commanding authority of moral excellence; none who revolt at the turpitude of crime; let conscience, at no point on the descending scale of profligacy, utter an admonition or forebode approaching wrath; let the being of a God be excluded from human belief, and the mind robbed of all idea of his perfections and majesty; let every element of that character which exalts him on the riches of the universe, as its beneficent Parent, and gives him the throne as its Almighty Sovereign and Judge, be done away from human thought, and then measure the efficacy of civil statutes on the conduct of men. Follow that child, who grows up without these restraints, through his profanity and strifes, and pilfering and thefts; his forgeries, robberies and murders, till he terminates his career on the gallows, despising alike the hand of his executioner and the wrath of his God; and you have no overdrawn picture of what every member of the community would be, under a similar exemption. What, then, would be the fact, were these restraints not merely removed, but every child, from early infancy, initiated into all the arts and excesses of vice, and every step of his progress animated by the counsel and the example of ruffians, old in crime, till he should become as much a child of hell as themselves! Oh, what scenes of wretchedness and horror would spread every field of observation! How should we see human selfishness in all that malignity and death which give to hell itself its moral aspect and its eternal woes!

4. We appeal to facts. Did time permit, we might trace the truth before us in a comparison of one Christian country with another; we might refer to different parts of our own country; and to that period of its history when infidelity and its practical licentiousness threatened “to subvert foundations.” We might recur to the history of England in the different eras of its moral light and moral influence. We might recur to the state of the pagan nations of antiquity, and show that, false and corrupt as their moral systems were they inspired an elevation of feeling and character which gave to society all its value. Though such appeals might furnish a convicting, they would not furnish the fullest illustration of the point we aim to establish. If we would justly estimate the evil of a corrupt public opinion, we must recur, not to examples of its partial corruption; not to examples where the subversion of Christianity has been followed by the morals of enlightened heathenism, but by the desecration of all that is pure, and exalted, and holy in Christianity itself, without any substitute; where it leaves too much light for the superstitions of heathenism to restrain man, and where by way of reprisal for its past odious authority, it is put down under all the ignominy and hatred of detected imposture. Passing by, then, the sufferings which so long distressed the nations, when popery took away from men the word of life, and substituted the commandments of men for the commandments of God; and the scenes of horror and of woe that desolated the nations under the reign of Mahomedanism, we have a memorable example, never to be forgotten, witnessed in our own age. In one country, and that the seat of arts, of science and of refinement, the revelation of God underwent a total eclipse. On that theatre of darkness, infidelity and atheism performed their horrid tragedy. Convulsion succeeded convulsion; every mound of authority was thrown down, and the voice of law, and the pleas of anguish, were alike drowned in the fury of the tempest. It was not a war of common atrocity; not a war for liberty or conquest; but a war of extermination of all that blesses man in time, and brightens his prospects for eternity. Men stuck the dagger of their enmity not only into the bosoms, but into the souls of men, nor did they deem their triumph complete till they had demolished every altar where human guilt had wept, and human misery been comforted; yea, till God and his Son were exiled from human thought. Law, order, civilization, were overwhelmed, as by the sweep of a tornado. The fires of hell kindled on the devoted land; and while the smoke of its torment ascended up to Heaven, Europe with its thrones trembled to its centre. And when we remember how the dark cloud rose over us, and how it looked like the preparation for the final storm, it becomes us to be instructed.

The subject leads us to the following remarks:

1. There is no form of government better than our own for a virtuous community; and none worse for a vicious community. In a monarchy and an aristocracy, where subjects are held in awe by the terror of military establishments, there is an independent sovereignty, which can augment its power, and enforce submission. But in a republic, rulers are governed while they govern; and in a virtuous republic, the people govern themselves by the ennobling influence of moral principle. Does liberty then consist in exemption from the grasp of despotism, and in doing our own will in accordance with enlightened duty and moral obligation? If this be liberty, where can it be found in perfection, except in a virtuous republic? And what is social happiness? What but the operation and effects of moral principle, of the fear and the love of God, and of the love of man, producing the whole train of social virtues, with their benign results? A moral influence, as it operates only on the reason and the conscience, is of mighty efficacy; operating on the heart, it gives perfection to human character and human happiness. This is not a dream. There is a world where this influence pervades every heart, animates every action, and reigns in the diffusion of universal blessedness. The same influence would bless earth, as well as heaven. And so long as sense and reason are left us, we shall look to this influence to bless this state; and so long as it shall here be felt, earth shall furnish no spot to rival this goodly land in the moral character and social happiness of its inhabitants.

But what is a republic without this influence? The people have no monarch to fear but themselves; no lords to whom they are vassals; their lords are dependent on them. Unlike a monarchy, or an aristocracy, a republic has no power of coercion by which it can reach degradation of principle and character, and compel visible loyalty from a spirit of rebellion. The government is the will of the people, and where that will becomes corrupt, as the prostration of moral sentiment will make it, everything is left to the fury of human passions, unchecked by power, or by principle. At the moment of such deficiency, human selfishness is lawless, and, from its woes, despotism is a welcome refuge. So sure then as a general corruption of moral sentiment shall pervade this republic, those principles of human nature which, unchecked, will invade human peace and happiness, will be found in the full play of their deadliest energies, in these fields, and streets, and dwellings, where all is now peace and joy. Then, highly as we prize our political institutions, grateful as we ought to be to heaven for the blessings they impart, should welcome monarchy, aristocracy, despotism, anything but a corrupt republic.

2. The subject suggests several reasons why we have to expect the continued efficacy of our civil institutions. Probably no state or nation has existed, in which there has been a combination of circumstances so favorable to the moral character of its inhabitants, as in this state, and of course none so favorable to the efficacy of political institutions. Here none are compelled to crime by the desperate state of their circumstances. Their employment, as an agricultural people, while it gives dignity to character, precludes, by a powerful tendency, a taste for the pleasures of sensuality and the vices of idleness. The husbandman, by his very occupation, is every placed amid the wonders of an omnipresent God, and summoned to praise him as the Great Parent of existence, and of all that blesses it. We are placed at a distance, also, from the wars and revolutions and crimes of older countries. What a mighty drama has been acting on the theatre of Europe, for the last age, while we have stood as on a safe and lofty eminence, to survey its horrors and learn wisdom from its follies and its crimes! Our political institutions have also secured, in no common degree, the great ends of social union. We have had, indeed, our political conflicts with their sins and calamities, but they have been without blood. There is a moral sentiment pervading the community, which demands the execution of many of our wholesome laws. There is a dark frown of popular opinion to meet open crime, and awe the gross daring of licentiousness and impiety. The sanctuary of justice has not been violated by the approach of bribery and oppression; nor has atheism been heard in the hall of legislation, to decree, amid the plaudits of an infuriated populace, the fool’s wish, “no God,” into a civil enactment. Religious liberty is not yet in chains. We are all born to feel, that no power on earth has a right to interpose between our conscience and our God, and that the prerogative of forming religious opinions, with its solemn responsibilities, is our own; a prerogative highly auspicious to the cause of truth and virtue. With the conviction that ignorance will make the place of its dominion “the region and valley of the shadow of death,” we look with joy to the institution of our common schools, by which provision is made to carry the light of useful knowledge, like the light of heaven, into every dwelling; and with still more bland emotion we look to our seminary of science, as the sun of the whole system, from which emanates a most benign influence on every department of social life, while it extends the light of salvation, and carries on the high enterprise of redeeming grace, in this state, in the neighboring states, and throughout the nation.

The Christian ministry in this state is distinguished by purity of doctrine, and the success of its labors. Without allusion to sectarian peculiarities, for I can easily overlook these distinctions in the present estimate, the clergy of our country, generally, are unrivalled in those qualifications which give to Christianity its effects on the conscience and the hearts of men. It is here that a laborious ministry brings the religion of the gospel home to the bosoms and business of the people, and makes them feel that they have a personal concern with it. It is here, if anywhere, that the sacred page of God’s revelation is opened, to show man his character and his destiny; that Christianity makes known her laws and her precepts, and reveals the bright visions of her promises, and the deep terrors of her denunciations. It is here, that she gives all her solace to human sorrow, and all her joys to human hope; and it is in this land that we seem to hear the exclamation—“Behold how beautiful on the mountains are the feet of him that bringeth good tidings, of good, that publisheth salvation, that saith unto Zion, Thy God reigneth.”

With that series of religious revivals which has blessed our country, in its power and extent, there is nothing to be compared, in any other portion of Christendom. While we can trace these footsteps of the Great Deliverer from sin; while his life-giving spirit departs not from us, this shall be the glory of all lands, and ours the privilege to blend the confidence of hope with the fervor of our petition—“Thy kingdom come, and thy will be done here as it is in heaven.”

Such are some of the principal causes of moral influence in this state, whose perpetuated operation will ensure the stability and the efficacy of our political institutions. So long as they exist, in their present state, the vital principle of our political existence will not be destroyed; it will still beat strong at the seat of life, for the requisite causes will exist to sustain a vigorous pulsation. We may indeed be agitated by political or religious commotions; ambition may project and execute and convulse; party conflicts may be even more violent than ever; error may spread its pestilential clouds and vapors; persecution may light its fires; foreign invasion may approach; the ark of God may be cast upon the floods; and the tempest may thicken and sweep around us—but Connecticut will be remembered by the Ruler of the storm, and in the hour of his mercy he will say to the winds, “cease,” and to the waves, “be still.”

3. Our subject suggests some of the principal sources of danger to our political prosperity. It is not believed that we have reached that prostration of moral sentiment, which resists the efficacy of all wholesome laws. The danger is that we shall reach it; and it is well to advert to the causes which may hurry us down this fearful declivity.

One principal source of danger is our party competitions. In this country we have, for many years, gone largely into the experiment of party conflicts. And who can assign limits to the ravages they had long since made, had a sound public opinion by shame and infamy, and moral sanctions, put no restraint on their feuds and their violence? Who has not seen their tendency, not only to proceed to every excess, which public sentiment would patronize or justify, but to corrupt that sentiment, and thus to remove every barrier to their own most baleful progress and calamities? Who has not seen enough to satisfy him, how easily the integrity of rulers, the majesty of law, and the sanctions of morality may be trodden in the dust before the march of party spirit?

Now we know that in a republic there are peculiar causes to augment the violence of contending parties. There are always enough to lead on the most desperate enterprises of ambition. There is a dependence of rulers on the people, which puts into the hand of the demagogue the most powerful engine of revolution, and which inspires a party with the consciousness of its own strength, and prompts its revenge and its excesses. There is in rulers a spirit of servile accommodation, which impairs the prerogative of government, and instead of maintaining the strait onward course of independent integrity, fearless of popularity or place, gives to “the voice of the constitutents,” the devotedness of an oracular annunciation; as if legislators had no further use, for either sense of honesty, than to ascertain and conform to the pleasure of those who give them their office. The extension, perhaps I ought to say the unavoidable extension, of the elective franchise, with the increasing unequal distribution of property, in this county with fearful probability, will one day operate in the violence and rage of party contests. A finer field is never opened for the career of unprincipled ambition, than when it can enlist its associates, and draw around it its dependants, and raise the outcries of faction, to redress the oppressions of the rich and the great. At the same time, no rights are dearer to most men than rights of property; there are none, the invasion of which is more sure to provoke resistance and conflict, or to awaken the most desperate struggles for their protection. Let then the state be convulsed, let party collisions become as violent and revengeful and excessive, as there are causes enough to make them, and how soon would every mound, reared by a sound public opinion on morals, be overflowed by the waves of popular fury! The men, on whom God should most visibly frown, would stand highest in popular estimation. From the hall of legislation, and the sanctuary of justice, would be heard the decrees of popular licentiousness. Crimes would be legalized by dignified example, by legislative license, and by judicial protection; and all the security, with which we now look at the joys of our pilgrimage, would be broken up, by the barbarities of anarchy, or the oppressions of despotism.

Another source of danger to our political welfare, is the declining estimate of the value of religious institutions. Long before the formation of our present Constitution, an increasingly low estimate of religious institutions was visible, in a considerable part of our population. Of this, a former law of the state, not the abolition of it, was, it is believed, a principal occasion. With the hostility which the law excited, was associated, to some extent, hostility to the object which it aimed to support. To this hostility, the repeal of the law, by gross perversion indeed, secured a triumph, and was considered, by many, not only as a release from the obligation to support religious institutions, but as a public sanction of the sentiment, that these institutions are unworthy of support. It thus gave to avarice the power, and to enmity to the gospel the gratification, of being avenged of their old enemies; and in many instances they have turned their backs on this only guardian of our political and social welfare. Neither the necessity of the change adverted to, nor the wisdom and the integrity of many who were active in producing it, is called in question. There were dangers and evils without the change, it is believed, greater than exist with it. All that is asserted is, that these perils have not wholly ceased. The danger is that future excesses will be the greater, as the consequence of former restraints; that this particular corruption of public opinion will increase, will withdraw patronage and support from religious institutions; reduce the “hire” of the laborers in God’s vineyard, and hold up the ministry of reconciliation as an object of suspicion and obloquy, till the message it brings from heaven will be despised and unheard; that custom and fashion will soon exempt a man from the disgrace which he merits for refusing pecuniary patronage to the institutions of divine mercy; that an indifference to the gospel, and an aversion to its grand peculiarities, will prevail, which will exchange it for damnable heresy; that those inadequate views of its benign efficacy upon the social state of man will obtain, which will consent to go without its weekly ministrations, and to leave posterity to grow up untouched and unblessed by its power; and that such contempt of the gospel, under the retributive providence of God, will exile that gospel from the land, bring on the community all the woes which mark its departure, in time, and lead away future generations from its great salvation, to the tribulation and the wrath of a ruined eternity.

Another source of danger is the difference of religious faith, and the sectarian zeal it awakens among different denominations of Christians. Contests, dictated simply by passion, are comparatively of feeble influence and of short duration. But those which are fortified, by the convictions of the judgment, are usually calamitous and lasting. Hence, religious differences are capable of exciting the passions of men, and perpetuating their animosities beyond any other cause. This has been well understood by the leaders in revolution, in every country. Never have they counted, with stronger confidence, on the adherence of their followers, than when they could enlist them through the medium of their religious partialities and zeal. It is in such contests, that animosities become the fiercest and the most relentless. Then, passion is sustained, in its utmost height, by the imagined rectitude of its cause, and from it, as the supposed cause of millions, even ferocity derives a steady impulse, to invigorate and sanctify all its movements. Then it is that the cause of truth and righteousness, which ought to be dearer to its professed votaries than every other, is abandoned for the cause of a sect; and the standard of moral action, the whole influence of religion in a community, is exposed to an effectual prostration. Then it is that infidelity and sectarian zeal, Herod and Pilate-like, find a common interest, and embark in a common cause; and the polluting union issues in death, to what is most beloved of God, and most desirable to man. In this country, the separation of Christians into distinct detachments, by its familiarity, loses much of its alarming aspect. We fondly hope that no apprehensions of evil, from this source, will be realized, but we cannot esteem them wholly groundless. While this separation exists to create uncharitable and exclusive spirit, while it converts every attempt to adjust external differences, into the occasion of exasperated feeling, and more distant alienation, the danger is, that the breach will continue to widen, that the cause of God will be relinquished for the cause of a sect, that professed love to God will be found in friendly concert and active co-operation, with infidelity and atheism; that a corruption of moral sentiment will pervade the community, to sanctify the excesses of passion in a cause deemed so holy; that jealousy of power on the one hand, and pretensions to it on the other; that superstition, in all its bigotry and impiety, in all its fury, will apply their combined energies to civil disunion, and civil conflict. Nor are there more fearful ingredients which an avenging God mingles in the cup of his indignation, when he would root up and destroy. Nor should it be forgotten that these very causes, which exist only in an incipient state with us, have, from similar beginnings, proceeded to these foreboded results; and that, by their help, even in this land, some future Cromwell may be seen.

Such are some of the dangers to which our political and social blessings are exposed. Some of the causes are inseparable from the nature of our government: all of them are in actual existence, and in actual operation. We may, indeed, flatter ourselves into security, with the dream, that something, we know not what; some redeeming spirit; some tutelary Genius, will protect and save us. No, my hearers, nothing but the spirit and genius of Christianity can save us. If we cannot uphold a moral influence, through the medium of moral sentiment, which shall be adequate to counteract these causes of ruin, then, as the ordinances of heaven go on to their appointed results, so will this republic descend, through convulsion and anarchy, to the vast cemetery of nations. All our dreams to the contrary will only hasten our descent to that fearful abyss.

4. Our subject calls on every friend of his country, to fulfill his part in upholding and augmenting a sound public opinion on the subject of morals. Among the most prominent and effectual means of this end, are the following:

In the character of subjects, the most important duties devolve upon us. The authority of God enjoins, that we “lead quiet and peaceable lives, in all godliness and honesty;”—that “every soul be subject unto the higher powers.” Whatever may be thought of the unqualified import of these injunctions, whatever may be said of the doctrine of passive obedience and non-resistance, undeniably there are rights and privileges of freemen; undeniably, it may be their duty to bring their influence to affect the issue of party competitions; and to redress injustice and oppression on the part of government. But it is maintained, that in this state, with a government and a people like ours, no good, but immense evil, must result from perpetuated party conflicts. In such circumstances, a thousand fold more injury is done by one party campaign of a few years, than any administration of our government will go right. On the contrary, if anything can make that administration go wrong, it is the influence of party zeal. If anything tends to corruption among the people, and oppression on the part of rulers, it is party zeal. Whatever party, then, be dominant, and whatever be the means by which it acquired the ascendency, yet when it has acquired it, our highest security, in regard to the wisdom and the rectitude of its measures, lies in an enlightened sound popular opinion. To secure this influence, and to prevent the ravages of party spirit, it is indispensable that the contest be abandoned; and, instead of committing our interests to the heat, and revenge, and maddening zeal of party commotions, we must place our reliance on the steady, unimpassioned energy of enlightened virtue in the people. Let the one cease, and the other pervade the community, and we shall exchange the darkness and fury of the tempest, for the clear shining of the sun, and the mildness of the zephyr.

Laying aside, then, our party contests, together with their jealousies and suspicions, let our hearts unite in a common interest. Let us remember that submission to the powers that be, which are ordained of God, is a duty which can scarcely need qualification, in this community. Let it be remembered, that injustice and oppression, on the part of government, are seldom prevented, but often provoked, by party contests. Let the political oracle, who is loud in the cry for improvement and change, be counted as he is, a political maniac; and the party zealot be eyed and scorned as the enemy of his country.

In the character of Christians, we have solemn duties to perform, in regard to the peace and welfare of the state. We have already adverted to the dangers and the evils, in this respect, of sectarian zeal and sectarian conflicts, when connected with political contests. Such dangers and evils are not fictitious; and they summon Christians, of every denomination, under solemn responsibilities, to union.

Every denomination of Christians should depend, simply, for the maintenance of its numbers, and its influence, on the purity of its doctrines, the sanctity of its morals, and the zeal and labors of its ministry. It always has been, and it always will be, an ultimate curse, to any religious denomination, to strengthen and build up itself by political patronage. If Christians are to be less concerned, for the cause of God and of souls, than for the success of their religious party; if sect is to clash with sect; if to augment their secular influence, and to pervert it to build up their cause, they are to become political factions; and if the community are to witness only their mutual hostility and contests, the most fearful results may be foretold with the certainty of prophecy.—Nothing, nothing can atone for “the broken unity, the blighted peace, the tarnished beauty, the prostrate energy, and the humbled honor of the church of God.” Every barrier, between the church and the world, would be swept away; ignorance of God and of duty would thicken apace, and the broadest sunshine of the gospel be eclipsed by the spreading darkness. Moral influence, the only safeguard of social order and social happiness, would cease from the community; and when God should come to make inquisition for blood, the death of whole generations would be found at the door of this disgraceful, guilty strife among brethren.

Let Christians, then, bury in oblivion their sectarian contests, with all those animosities, jealousies, and suspicions, which mar their intercourse. Without a pretence of differing on essential truths, or that each sect has not every desirable means of promoting the cause of God, what can justify alienation, and mutual competitions? When, by union and concert, we might do so much to uphold and extend that influence which the wisdom of God has appointed to bless men, in time and eternity, what can justify us in wasting our strength in the work of proselytism, and for this purpose merging the Christian in the sectarian, and the sectarian in a political partisan? Ah! Brethren, we want more of the sacred fire that glowed in the breasts of the early Christians; more of the spirit of heaven; more fellowship with angels, with God and his Son, in the work of bringing men to repentance and to salvation. God calls his people to other service than mutual contention. While the enemy, rushing in like a flood on the one side, calls us to defend a common Christianity, the field, whitening to the harvest on the other, invites to its toils and its rewards. “The New Jerusalem is descending from God out of Heaven,” and we seem to hear “voices in heaven,” voices of acclaiming gladness, saying, “the kingdoms of this world are becoming the kingdoms of our Lord and of his Christ.” Let us, then, open our hearts to higher and nobler inspirations. Let us strike our hands in a covenant of love; let our hearts accord with the designs, and our efforts keep pace with the movement of God’s beneficence. Then shall the church of God be one, and secure, from the most profane, the acknowledgment of her divinity in the blessings she bestows on our land. Then, in firm encounter, her sons shall meet the legions of error and of death, and go on to new triumphs, till earth shall hear and welcome the salvation of God.

As members of the community, and especially as those who have authority and influence, we are called to counteract vice, and to uphold the institutions of religion. What might not be done by men of talents, and wealth and influence, to change the moral aspect of a whole State; and to cause it to assume, as it were, the face of another Eden? And why do they not do it? Because they want the heart.—I know that every plan of moral improvement is met by the paralyzing prediction, that nothing can be done. I know too, that there is a point of moral degeneracy from which a people will not choose to rise, and from which God will not choose to raise them. But heaven forbid that we should have reached this place of despair and woe. Nor do we believe, that there are no existing laws which can be executed, and especially that no laws can be formed, which can be executed, for the suppression of Sabbath breaking and drunkenness. Which is the town in this state, a majority of whose freemen, would not approve and support decisive measures for such a purpose? There is yet left a correctness of moral sentiment, which would uphold any legislature, who should strenuously bring the power of its provisions to bear on these evils. Nay, there are friends of good order and good government enough to create a sound public opinion, that shall secure an active co-operation with legislative efforts, which neither the sectarian, nor political partisan can withstand. Criminals, and the abettors of crime, are cowards. Conscience and God are both against them. And let the civil statute, and public opinion, be arrayed against them, and their defeat is certain. At any rate, let the experiment be tried; and let us have the appalling decision that nothing can be done, if at all, as the result of thorough experiment. Look at the ravages of the single crime of drunkenness, in families, in neighbourhoods—go to your poor-houses and prisons, and see the prostration of moral principle, what desolations of domestic peace, what crimes, and woes, and death, it spreads through the land! What a tax every sober and industrious member of the community has to pay for the support of this soul-destroying sin. More than nine tenths of the poor-tax of our country result from this single cause. Think of nearly fifty millions of dollars of annual expenditure in this nation, for strong drink. See how this crime associates with it every crime and every woe;-sabbath breaking, profanity, idleness, lying, fraud, the extinction of natural affection, theft and murder, and sorrows, griefs and broken hearts, ruined parents, and a ruined offspring. It is no exaggeration. Look, and you shall see the raging of a pestilence, before which the bloom of paradise would wither. And must we only sit still to contemplate its desolations? Shall sectarian and party zeal, to secure the auspicious patronage and support of drunkards, consent to defeat this cause of humanity? And every heart be cold, and every hand idle, as if panic struck by the fear of popular odium? Then, a few generations passed, and we are a ruined people. Liberty and religion will here mingle their tears of despair over all that man holds dear and God counts holy.—Oh, for some spirit of emancipation—that some Howard, or Clarkeson, or Wilberforce might rise up to set us free from this bondage, or to alleviate its horrors; embarking all his talents in the enterprise, and persevering in it, in defiance of every obstacle. Never was there a finer field for benevolence and philanthropy to shed abroad their blessings; never a cause, which might better draw around it adherents from the friends of humanity, and secure the active concert of every virtuous member of society. Would it not be well if any of the wretched victims of this vice could be reclaimed? Would it not be well if our sons and our daughters could be saved from entering the same path of woe? Would it not be well if every virtuous member of the community, every legislator, and every executive officer, and every parent, and every friend and brother could be enlisted in the cause, and if an influence of counsel, and warning, and example, of shame and infamy, and legislative provision, and of a sound public opinion could be made to reach every member of the rising generation, that should check the career of so many thousands whose steps take hold on hell? And would not the man, who should commence the work, and prosecute it with any measure of success, call forth the warmest tribute of gratitude from his country, and stand high in the approbation of his God?

Not less imperious is the duty of upholding the institutions of religion. Our argument, on this point, is not now drawn from the interests of eternity. It is simply an appeal to patriotism. If men had no souls; were there no judgment day; no preparation requisite for the immortal state; the well-being of society, in time, demands the support of Christian institutions. These are the institutions which divine wisdom and mercy have appointed to bless man on earth. Without them, the laws of civil government, salutary and indispensable as they may be, are but a cobweb provision. The great ends of government must fail in every nation, without national morality. This is well understood by the friends of revolution, in every Christian country. When they would corrupt, and overturn, and destroy, their first and most sanguinary measures have been directed against Christian ministers and Christian institutions. Change, innovation, revolution in a community, where religious institutions exert their proper influence, are hopeless.—These must first be brought into contempt, and when this is done, the work of ruin is complete. Even the wiser heathen knew this, and defended their religious rites with a spirit and a wisdom which disgrace many in this enlightened country. Let then the friends of their country, and of social happiness, be as wise as their enemies. Why should they not understand where their strength lies, and be as solicitous to preserve it, as the invaders of national happiness and prosperity are to destroy it? Why should not legislators, judges, magistrates of every description, with every friend of his country, uphold those institutions which are its strength and its glory? May not institutions, which the wisdom and goodness of God have appointed to bless man in time as well as in eternity, be upheld without intolerance and persecution? Are we thus prepared to libel their Author, and, for the sake of liberality and charity to men, are we to have no charity for the living God; and, to show that we have none, by laying aside his ordinances as useless? Shall clamors, about the rights of conscience, induce us to throw away Heaven’s richest legacy to earth? Shall the murderer plead the rights of conscience, for the privilege to kill, and the incendiary for the privilege to burn? Has any man rights of conscience which interfere with a nation’s happiness? Or is it yet to be made a question, whether Christianity be not a wretched imposture; whether it have a salutary influence on civil society? Have we, in this land, to hold this point as yet in debate? Can we decide that theft, and robbery, and murder are evils, and yet not decide whether the influence of the gospel of God be to bless or to curse those who feel it? Is it right to punish crimes which invade social peace? Does the public welfare demand it? And yet is it persecution so to bring the light and influence of moral truth to bear on the mind of man, as to prevent these crimes? But you will make men Christians. And what if we do? The sin is not unpardonable. Besides, is it not as truly an act of kindness to make men Christians, by the exhibition of duty and its sanctions, in the light of God’s truth, as it is to make men infidels and atheists, by means of falsehood and sin? But you’ll make sectarians. God forbid. We plead for no such influence. We only ask for those provisions of law, and that patronage from every member of the community, in behalf of a common Christianity, which are its due, as a nation’s strength and a nation’s glory. In this country, and pre-eminently in this state, the unity of our councils, the vigor of our government, our laws, our habits, have resulted from the moral influence of Christianity. Annihilate this influence, and you bid he soul depart, and prepare a grave for our liberties, our religion, our morals, and our happiness. And who would put his hand to this work? Who are the men that would empty our sanctuaries, and our pulpits; break down the Sabbath, and all the institutions of Christianity; and exclude its influence from their own minds, and the minds of their fellow beings? They are men who would extinguish the idea of Jehovah in the mind of man, as if that were the most painful to human contemplation, and the most destructive to human happiness! Great God! What deeds of horror have these men to perpetrate, that makes them thus dread thine inspection? Unhappy, wretched men! The presence that enraptures Heaven is their chiefest torture; nor can they find relief but in the persuasion that the world is forsaken of its God!—Are these men to be listened to! No—brethren, they are the enemies of God and man, and so ought they to be accounted.

Let us then remember that the safety and welfare of nations is not to be chiefly sought either in arts or in arms—and that the utmost barbarity may be united with the highest refinement. We may dream of a philosophical millennium, and banish the fear of God and dependence on his mercy; but he who ruleth among the nations has fixed the laws of national prosperity. By his resistless decree, no vigor of the body politic can long survive the decay of religious institutions. No wisdom or policy, that despises the power of his Gospel, can withstand that wrath of the Almighty by which he avenges his abused goodness. Let then every friend to his country do what he can to secure to Christian institutions their place and influence in that system of means which God has appointed to bless humanity in time. Let the being of God, as the ever present Ruler and final Judge of men, be recognized. Let the Saviour’s name be adored and trusted. Let “the teaching Priest” be heard in the sanctuary—Let the Sabbath be consecrated as the day of salvation. Let the family and the school be the nursery of youthful piety. Let the magistracy of our land, by a faithful execution of the laws, become a terror to evil doers, and the praise of them that do well. In a word, let all those institutions be upheld, by which God would bless, and we shall be blessed. Angels or embassies of love will still visit our land, and minister to the heirs of salvation. The spirit of grace will still breathe on the dry bones of the valley and quicken to immortal life. The Saviour will be satisfied with the trophies of his mercy. The sun of our nation’s prosperity will rapidly rise to its meridian, and the voice of a reigning God, command it to stand still in fullest splendors.

The application of our subject, to the civil authorities of our State now assembled, is obvious.

Respected Rulers, while the pulpit is not the place to discuss measures of state policy, nor to offer the incense of flattery to any one administration, or to regale the passions of any political party, I am happy in the conviction that I need not hesitate to employ it in speaking of some of your duties to “the blessed and only Potentate.” “The powers that be are ordained of God.” To you, then, under God, we look, in no small degree, for the perpetuity of our civil rights and social blessings; not only by the wisdom of your laws; not only by acts, to encourage the industry and commerce of our state; but by giving your countenance and patronage, your private example, your public influence, to uphold that standard of public morals which is the only pillar of society, the only safeguard of nations. High responsibilities pertain to your station. You live not, you act not, merely for yourselves. Your influence will outlive you; your virtues will survive these tabernacles of clay; your errors and vices will not go down with you to the tomb. They will alike reach future generations, and be felt in other worlds. On the one hand, by disregarding the means of national morality, by indifference or hostility to God’s appointed means of national happiness. You may become accessory to the profanation of the name and of the Sabbath of God; you may silence the embassy of his grace, and extinguish the light of salvation; you may even direct the midnight robber to his neighbor’s dwelling, and put the dagger into the assassin’s hand. On the contrary, by the contribution which your countenance and example as men; your acts and measures as rulers of the people, may tend to sustain Christian institutions, and to uphold a correct standard of morals; you may exert an influence that will descend to save and to bless, till the latter day of glory. Virtue and piety have a peculiar lustre to awe and to attract, when adorned with the rays of honor and authority. While, then, it is the desire of some to shine, and of some to govern, and of some to accumulate, be it yours to execute the high prerogative of ministers of God for good! The time is short–one 1 whose presence has often honored this anniversary, and who occupied a distinguished place in your councils, is no more. We lament the death of the able jurist, the upright counselor, and the wise and honorable magistrate. We revere his virtues, and would embalm his memory as a faithful servant of his God, and of his country. You, his associates in public life, and public responsibility, must soon follow him to his last account. And when the distinctions of earth shall pass away; when death shall take from rank its pageantry, and from royalty its crowns; what will then cheer the retrospect of time, and gladden the anticipations of eternity? Not to have heard the plaudits, and drawn the gaze of men; not to have been breathed on by the applauses of your fellow worms; but to have been actuated by that ennobling principle, which reason ratifies, and conscience approves; which God enjoins, and his spirit inspires—that of being and doing good. And then, too, how endeared will a seat in glory be, whence you shall look down on earth and see, as the effects of your instrumentality, the joys of social life, and preparation for eternal glories, perpetuated through future generations; how will it swell the joy of that world, to meet from this, through the ages to come, your brethren and kinsmen, according to the flesh, bringing their crowns of immortality, and laying them at your feet as an acknowledgment of your influence in imparting to them the bliss of such an inheritance!

1 Lieut. Governor Ingersoll.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!