Born the same year that Congress penned the Declaration of Independence, Bates grew up helping with the family farm and serving as a clerk in the family store. Self-taught, he was able to enter Harvard in 1797 as a sophomore, and after three years he graduated with honors. He then took a teaching position at Philips Andover Academy, which is how he earned his living while studying theology. Ordained in 1803, he became pastor of the Congregational Church in Dedham, Massachusetts, until 1818, when he became President of Middlebury College, a position he held until 1839. After retiring from Middlebury, Bates served as the chaplain of the United States House of Representatives from 1839-1840. Former President John Quincy Adams was a member of the House during the time he was chaplain, and when Adams died eight years later in 1848 (following seventy years of public service in America’s behalf), Bates delivered the following sermon eulogizing Adams.

A DISCOURSE

ON

THE CHARACTER, PUBLIC SERVICES, AND DEATH,

OF

JOHN QUINCY ADAMS.

BY JOSHUA BATES.

WORCHESTER:

PRINTED BY SAMUEL CHISM.

218 Main Street.

DISCOURSE.

Know ye not that there is a prince and a great man fallen this day in Israel.

2 Sam. Iii. 38.

“Know ye not that there is a great man fallen?” This inquiry, or rather announcement, made in Judea, three thousand years ago, might, with great propriety, have been made in our country, when recently John Quincy Adams, under the sudden stroke of disease, sunk down in his seat in the Congress, and soon after died, still within the walls of the Capitol of the United States.[i] Indeed, the announcement was made, in language scarcely less forcible and impressive, not only at Washington, but, through the whole land; was made and sent abroad with lightning speed, with telegraphic dispatch. And everywhere, as the tidings spread, the involved sentiment seems to have met a ready response, and been echoed back, in soft and solemn tones, – “A great man is fallen.”

Nor should we, my hearers, though far removed from the exciting scene of his death, and dwelling in a retired village, suffer the announcement of the solemn fact to pass by us, or the recollection of it to escape from our minds, without some special notice of the event itself, and some practical application of the instructions which it brings along with it. I repeat the language of the text to-day,[ii] therefore, not for the purpose of comparing the event, to which I apply it, with that to which it was originally applied by David, the king and sweet Psalmist of Israel; nor for the purpose of tracing analogies and running a parallel between the great man of old, whose death David announced to the children of Israel, and him, whose death, at Washington, has been recently announced to us. I adopt the language of the text, merely as a suitable and striking introduction to a discourse, on the character, public services, and death of this great man of Massachusetts, of New England, of the United States of America, of the world; who has thus fallen, full of years and crowned with honors. Accordingly, I shall endeavor to delineate a few of the most prominent features of his character, and speak of some of the most striking occurrences and actions of his life, which conspired to constitute him “a great man.” And I intend to intersperse the whole with such reflections and practical remarks, as seem adapted to the condition and claims of our country; and as are calculated to remind us of our obligations, and prompt us to the faithful discharge of duty, as members of civil society and citizens of a great republic.

With this view I must detain you a little while, with the definition of terms; and occupy a few moments in showing what are the elements of greatness in human character – what constitutes a great man.

Clearly all that is sometimes called great, is not truly great. Greatness in man, evidently does not depend on position in society, on place and power, on office and rank, on pedigree and primogeniture; on the ten thousand nominal and factitious distinctions which have been arbitrarily made in society. For the most elevated rank and the most honorable titles are often assumed by men of the lowest minds and vilest character; and not unfrequently the highest civil offices are conferred on the weak and the wicked. In hereditary governments, the chances are, at least equal, that his will be the fact; whenever an heir-apparent ascends the throne; because he ascends, of course, without regard to character or qualifications. And even in elective states, want of judgment in the electors, deception practiced by selfish aspirants, and the blinding influence of party spirit, too often produce the same results. Thus the high places in civil society are sometimes filled by men of little minds, and destitute of all moral and religious principles. And the ultimate consequence is, that the wicked walk on every side, when the vilest men are thus exalted. Then vice and iniquity every where abound, drawing down upon the country the judgments of Heaven.

Nor will the possession and development of some one high quality alone, make a great man. A man may be a great mathematician or a great poet, a great general or a great politician, and yet be destitute of that, which is absolutely necessary to constitute a great man. Yes, even the best moral qualities may be seen in connection with much intellectual deficiency; such weakness of judgment, wildness of imagination, or instability of purpose in a man, as to forbid the application of the epithet great to him as a man; however, charity may wink at his errors, smile at his foibles, pity his misfortune, and yet praise him for his good intentions.

But we may remark positively, that great intellectual faculties and high moral powers, fully developed, properly directed, and actively employed, are all requisite to make a truly great man. Or, to express the same thing in different language, we may say, a great man must possess, at once, symmetry and elevation of character. His original powers of mind and susceptibilities of heart must be of a high order, cultivated with care, drawn out and kept in such just proportion and steady equilibrium, as to produce a finished character – firm and elevated, beautiful and sublime. Or better still, perhaps, we may say: a great man must show his greatness, by standing on high ground, where his light may shine and he may be seen; and by there exhibiting those excellencies which are involved in a faithful and diligent discharge of the duties, growing out of all the relations of life and immortality.

He must, therefore, be a man of firmness of purpose and decision of character; of self-possession, self-culture, and self-control; and all these qualities he must possess in such measure, as not only to secure his own happiness, but to be able, most effectually, to promote the happiness of others – of all others, who are dependent on him and connected with him. He must be prepared to discharge faithfully and successfully all the duties which his social and civil relations impose upon him; prepared for the service of his country and generation; prepared, especially, for the service of his God and the enjoyment of his favor forever.

Hence, though there may be degrees of greatness in character, and, of course, different classes of great men, yet the number of those who are truly eminent, and are entitled to the high distinction denoted by the epithet, is, in every age and country, comparatively small. For, as we have said, no one can be truly great, without possessing great original powers of mind; nor unless these great powers are fully developed, carefully cultivated, properly directed, and faithfully employed.

These cultivated and well-directed powers, I repeat, may exist in different degrees and various proportions, in different men; but in whatever degree or proportion they are possessed by any one, and in whatever relation or office he may be placed, if truly a great man, he will be found always prepared to meet the calls of duty with promptitude and decision, and to pursue the path of duty with untiring assiduity and never-yielding perseverance.

Especially, let it be remembered, the religious element is indispensable to constitute greatness of character in man. All other powers and qualities, however exalted and apportioned, will fail to produce true greatness, without the combining and controlling influence of this high quality. To render them subservient to the purpose for which they were bestowed, or even to secure their salutary tendency, they must be sanctified by religious sentiment, and exercised and employed under the direction of religious principle.

This element of greatness in character, has, indeed, been generally overlooked or forgotten. Hence, talents of the most brilliant order have been wasted; genius permitted to run wild, and scatter abroad the seeds of death; and knowledge, though extensive and powerful, suffered to lie dormant, or become merely the power of producing mischief and misery in the world. Hence the great general (so-called) has sometimes become a cruel murderer, destroying without mercy and almost without thought, the innocent and defenseless. Hence the great poet (so-called) has sometimes become a trifler, a madman, a corrupter of youth, diffusing everywhere a mortal pestilence – error, ice, and wretchedness. Hence, too, the great statesman and politician (so-called) has sometimes become a selfish demagogue, a fraudulent diplomatist, a cunning aspirant for power, and a cruel oppressor when in power. Thus greatness (so-called – falsely so-called) sinks into littleness, into meanness even when separated from goodness. Yes; all talents, however brilliant; all knowledge, however extensive; all developments of mental power, however mighty; all acquisitions of science and learning, however comprehensive; all natural sympathy and even moral sensibility, however exquisite; unsanctified by religious truth and uncontrolled by religious principle, will forever fail to produce true greatness of character, or render any one truly a great man. They need one essential ingredient to form the compound. They want the combining and conservative element, the purifying and controlling power; that, which alone can give consistency, permanency and excellence; unity, beauty and sublimity, to human character; or render a man of great powers and acquisitions, truly a great man.

Yet, as few as men of greatness of character are – here and there one in an age, like light-houses scattered along the sea coast, to guide the bewildered mariner – our country has produced her full proportion; and John Quincy Adams was decidedly one of the number. Yes; he possessed all the elements of greatness, and most of them developed in a high degree, harmoniously combined, well balanced, and steadily employed, under the direction of enlightened conscience and fixed religious principle.

His native powers of mind seem to have been of a high order. It may, perhaps, be thought by some, that his great attainments in literature and science, depended more upon his superior advantages for improvement, than on native vigor of intellect. It must indeed, be admitted, that his advantages were uncommonly great, and eminently calculated to develop his original powers of mind, and urge them forward to maturity. Born at a most interesting period in the history of the country,[iii] just as she was entering into her mighty struggle for independence, of parents deeply involved in the counsels and measures which led to that struggle and carried it through with success; rocked in the cradle of liberty and science, and nursed in the arms of piety and patriotism, his first impressions and earliest developments were unquestionably favorable to energy of character, enterprise of spirit, and that greatness to which he ultimately rose. Especially was the influence of his excellent mother manifest in giving direction to his high pursuits and forming his elevated character, both intellectual and moral. Under her superintendence his literary career, as well as his moral. Under her superintendence his literary career, as well as his moral and religious training, was commenced.[iv] And, even when withdrawn from her personal influence, by his residence with his father and others in Europe, he failed not to receive her high counsels through the medium of those excellent letters which are already before the public.

At the age of eleven years, he began to study foreign languages, both ancient and modern, in a foreign country; and, before he had reached the age of twenty, he had completed a course of liberal education, having pursued his studies at two universities,[v] besides receiving the best tuition at home and abroad; and, at the same time, enjoying the advantages of travel and extended observation, in daily communion with some of the greatest minds and ripest scholars of the age.

But, while all this is admitted, it must be seen in the result, that the mind which could appreciate these advantages, meet their high claims on his energy and diligence, improve them all without distraction or weariness, and grow to maturity under their pressure and multiplied appliances, must have been a great mind; must have possessed happy tendencies and strong capabilities. I am not, however, anxious to settle this metaphysical question, and balance the weight of evidence between the claims of original talents and a judicious, energetic, and persevering improvement of facilities and favorable opportunities. It is enough for our purpose, that we are able to affirm and prove, that he possessed great powers of intellect, fully developed and completely disciplined; a mind of enlarged capacity, and well furnished with the richest stores of learning.

His opportunities for observation and the various circumstances of his early life, were surely favorable for the acquisition of knowledge. But still, his perceptive faculties must have been acute, and his powers of attention and abstraction must have been great, or these opportunities and favoring circumstances would have availed him little; certainly would not have made him the ripe and universal scholar that he was. Similar advantages have been enjoyed and abused by thousands. Thousands, like him; have traveled in foreign lands, conversed with great minds and learned men, and received instruction in the best schools, who, nevertheless, wanted the capacity or energy of mind requisite for scholarship; for high attainments in literature and science; – not unfrequently have they come out from the university “graduated dunces,” or returned from abroad, “traveled fools.” He had the opportunities for improvement, it is true; and he improved them; because he possessed the capacity to receive and retain, and the energy to pursue and acquire knowledge.

We may, at least, affirm without the fear of contradiction, that his memory was extraordinary, perhaps unequalled. I discover, however, nothing in his course of education peculiarly calculated to form such a memory; nothing but what is common to the discipline of a liberal education, with a steady exercise of the faculty, and a practical application of the knowledge acquired. I know not, that he adopted any rules of arbitrary association, in order to strengthen his powers of retention and recollection; that he took any special pains to commit to memory, for the purpose of exercise and discipline; or that he reviewed what he read more frequently than other sound and finished scholars. I see nothing, indeed, connected with his mental habits, peculiarly favorable to the improvement and enlargement of this intellectual faculty, except his early and continued practice of committing to writing, every day, the most important occurrences of the day, with his own views and reflections. But this practice can scarcely be said to be peculiar to him. Others have done the same thing; and some, perhaps; with equal care and particularity. And yet his memory was certainly extraordinary; perhaps unparalleled, both as to its extend, retention, and readiness. He seems to have taken notice of whatever occurred within the sphere of his observation; to have read whatever came to his hand, worthy of being read; and to have retained, and kept in a state of readiness for use, whatever of knowledge he had acquired, both by reading and observation.

It has been said, that readiness and retentiveness of memory are qualities inconsistent with each other, and not to be found in the same person; because they depend on antagonistic habits of association – the one belonging to the philosophic mind, and the other to the practical man of business. But in him we have an example of their perfect consistency and complete union. His memory was both philosophical and particular; both a retentive and a ready memory. What he had once learned, as we said, he seems to have retained always; and what he thus knew, he had always at command, and ready for immediate and appropriate use.

The consequence of his great powers of memory, happily directed by the course of his education, and faithfully applied by his great industry and persevering energy of research, was, as already intimated, the acquisition of extensive and various knowledge – knowledge laid by in store, and yet held ready for use, whenever occasion called.

He was more or less acquainted with many of the modern languages of Europe; and several of them he could speak and write with readiness and accuracy.[vi] In the classical languages of Greece and Rome, and especially the latter, he read much, and he was thoroughly acquainted with the literature which they embodied. He was, too, a man of science; wonderfully catching the spirit of the times, and keeping along with the rapid progress, both of the abstract and the natural sciences. But his knowledge of history, natural law, political economy, and the science of legislation and civil government, constituted his chief attainments, and furnished the mighty resources and high qualifications which he possessed for complicated action in public life, and the various services of his country to which he was called.[vii]

His unrivalled power in debate, depended more on his inexhaustible fund of knowledge and ready memory, than on any distinguished qualities of eloquence or peculiar graces of oratory. He always overthrew his antagonists on the political arena, because he was always clad in panoply complete – armed cap-a-pe, with sword in hand, sharpened and burnished, and ready for action. When pursued with objections, inquiries, and rash statements, as he sometimes was in Congress, and even with a spirit of bitterness and reproach, his resources of mind never failed him; his answers were always ready, his replies conclusive, his retorts keen; confounding his assailants with an array of facts which no man could gainsay, and a conclusiveness of argument which no man could resist.

It has been said, that no man ever attacked him wantonly, in a deliberative assembly, with impunity; that whoever presumed thus to assail him, might be sure of defeat – yes, if the combat was continued, of political death. An illustration of the truth of this remark occurred in Congress, a few years ago, when he was suddenly attacked by a combination of talents and a conspiracy of interests and prejudices, with a view to his expulsion from the House of Representatives. How expertly did he resist the attack on the right hand and on the left, in front and in rear; and how completely did he put the combined forces of his assailants to flight, and scatter them to the four winds of heaven! During the first session of the twenty-sixth Congress, I remember, that a similar, though not so violent attack, was made upon him, with a similar result; and I remember, when the remark was subsequently made to one of the members of the House: “Why, Mr. Adams seems to know more than any of you,” the prompt reply was: “Yes; more than all of us together.”

Another trait of intellectual character in Mr. Adams, which ought not to be passed without notice, is imagination. This faculty, however, was certainly not so prominent in him, as was that of memory. The two faculties, indeed, are never displayed, in very eminent degree, by the same person; because they depend on principles and habits of association differing from each other, and counteracting each other’s operation. Memory depends on arbitrary connections, gross resemblances, and scientific classifications; but imagination on slight analogies, shadowy visions, ethereal views, and transcendental flights of fancy. A rich, poetical imagination, therefore, is seldom found in connection with a giant memory.

His imagination, however was by no means deficient. Some of his poetical effusions have been very favorably received by the literary public. But if he was not eminent as a poet, he had sufficient power of imagination for the purposes of vivid conception, graphic description, forcible illustration; enough to constitute him a sound and dignified orator; enough to secure to him the title of “the old an eloquent,” as well as “the eloquent young man.” His eloquence; however, did not depend on voice, or attitude, or playful gesture, but on

“Thoughts that breathe

And words that burn,”

on clearness of views, extent of knowledge, closeness of reasoning and soundness of judgment, expressed in appropriate and forcible language, and addressed to the understanding and the heart.

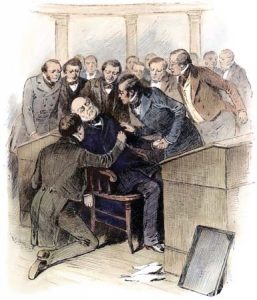

I well remember, with what dignity and commanding eloquence he rose, on the 5th of December, 1839, in that tumultuous assemblage of the Representatives of the people of the United States, who had been four days in the great hall of the Capitol, without a chairman and without order, trying, but trying in vain, to organize a House. He rose, after having waited in silence till a crises seemed to be at hand – he rose – I seem to see him now – he rose, and, with his piercing eye, his slowly waving hand, and shrill voice, already enfeebled by age, he soon calmed the troubled elements, “and stilled the tumult of the people.” The result is known. But what the result of that party-strife would have been, without his influence, no one can tell. It might have issued in a continued disorganized convention, or a complete dissolution of the government.

Mr. Adams, we may add, was a man of great decision of character, firmness of purpose, unflinching moral courage. So prominent was this quality of his mind, that he was sometimes thought to be too unyielding, and even obstinate. But time has generally shown, that what bitter enemies and timid friends called willfulness and self-sufficiency, was conscientious firmness – a determined adherence to what he viewed as right – that it was conscience and not self-will that held him to his purpose. Witness his long contest and arduous struggle in Congress for the constitutional right of petition – a contest in which he sometimes stood almost alone; but one in which he never yielded, nor relaxed his efforts, till he carried his point, and convinced both friends and foes, that he was right, and that he had been conscientious in contending for the right.

It was this high quality of firmness and independence, of conscientious adherence to the decisions of his own judgment, which caused him, as I verily believe, so often to break off his connection with those who had claimed him as a partisan. He was too conscientious and independent to be held in the trammels of party. Of course, he has been claimed, at different times, as a member of the several political parties, which have existed in the country, but he was never completely identified with any. Bred in the school of Federalism, he embraced and generally maintained its doctrines, during the administration of Washington and his father. But, when an occasion occurred, where he thought the policy of the party wrong, he acted promptly on the other side of the question. Believing, as he declared, that the rights of our oppressed seamen demanded stringent measures to bring the British government to regard the humane law of nations on the subject of impressments, he left the ranks of the opposition, and fell, of course, into the measures and the ranks of those who supported the administration. He might have been wrong in his judgment; at the time I thought him wrong; and I am not yet convinced, that the unnatural war which followed the stringent measures of the Embargo of 1807, might not have been avoided, and thus much blood and treasure saved. But he thought otherwise – honestly thought, as I now believe; and accordingly made the strong declaration, for which he has been often and severely censured: “Mr. President,” said he, addressing the presiding officer of the Senate of the United States – “Mr. President, I would not deliberate, I would act.” I well remember the indignation which burst upon his head, from his former friends and his father’s friends. Yes; I remember, when a grey-headed man pointedly reproached him in a public hall, where he could not, with propriety, vindicate his conduct; and I remember the meekness and firmness with which he bore the reproach. The rebuke was certainly untimely; and the indignation, if, as is generally believed, he acted according to his judgment and conscience, was unjust. Indeed, the language which preceded his vote for the Embargo, upon this supposition, was not rash; it was sublime; it was nobly said: “I would not deliberate, I would act.”

By this course he was brought, as I said, to sympathize and act with what was then called the Republican party; and with them he continued under Madison’s and Monroe’s administrations, till that old division of parties sunk into obscurity, and he was brought into the presidential chair. But here he found many of his opinions so much at variance with the interests and prejudices of some with whom he was called to act, especially with regard to internal improvements, the regulation of a tariff, the proper treatment of the Indians, and the still more embarrassing subject of slavery, that the course of measures, which he felt himself compelled to recommend, deprived him of a second election to the presidential chair – an election which he might have secured, if he had been willing to sacrifice his judgment and his conscience, or resort to the power of perverted patronage and political proscription.

Finally, by this independent course he became the champion, and, for a time, the favorite of a new party, through whose influence he commenced his long and laborious career in the House of Representatives. But to meet their wishes and sustain their proposed measures, he could proceed no farther than he felt himself at liberty to go, according to his views of the provisions of the Constitution, and the implied contract with the States of Virginia and Maryland, in the cession of the District of Columbia to the jurisdiction of the United States. Here again some thought him self-sufficient on the one hand, or too scrupulous on the other. But, whether right or wrong in judgment, he was honest and firm in purpose. Thus has he been called to act, in the measures which he approved, with all parties; but he belonged exclusively to none. Thus did he beautifully illustrate the character of decision, firmness, and moral courage, which constitutes a great man, acting as an independent republican.

One other general characteristic of his mind, or rather of his heart, I am constrained to mention: his susceptibility of emotion, his strong passions, his ardent feelings, his acute sensibility. But strong as his passions were – and they were confessedly strong and easily excited, – they were always under the control of his will, and subject to the guidance of his reason. In his highest sallies of indignant eloquence and withering sarcasm; in his most vehement retorts upon his antagonists in debate, he never said what he did not believe to be true; and seldom what he could not prove to be both true and just. Under the most powerful provocations and the strongest excitement, his understanding remained undisturbed, his conceptions clear, his inexhaustible treasures of knowledge at command; and he never failed of vindicating the positions he had taken against the assailing powers of talent, and eloquence, and prejudice; and to the complete satisfaction of all enlightened, impartial observers.

“Always?” – “Never?” did I say? Perhaps this language is too strong and sweeping. He was a man; and it is human to err. He may have made mistakes; he may have indulged unjust suspicions, and thrown out unkind insinuations. Unquestionably he sometimes did. But was he not always ready to explain, where he had been misapprehended? To make reparation, where he had injured? To forgive, where forgiveness was asked? To be reconciled, where alienation had unhappily and inadvertently taken place? Would time permit, I could state cases and relate anecdotes, which would furnish a favorable answer to these inquiries, and satisfy every candid mind.

He was, indeed, as we have said, a man of strong feelings and acute sensibility; and the wonder is, that his self-government was so nearly perfect as it was; that amidst all the storms of debate, through which, in high party times, he was called to pass, and under all the violent personal attacks of deliberately-formed conspiracy against him, he was able to control his feelings, so as to command the resources of his mighty mind and inexhaustible memory; so as to throw back upon his assailants the scorching and withering eloquence of truth, and reason, and indignant rebuke.

Yes, he was a man of feeling – of tender as well as strong feeling. Often have I seen that feeling exhibited in his changing countenance, and even falling tears, under the preaching of the gospel of Christ, in view of the melting scenes of Calvary, and under the pressing influence of the doctrines which cluster around the cross. Is it improper to say, (for I speak what I do know,) that he has been seen, as he sat in the Clerk’s seat, on the Sabbath, in one of the halls of Congress, with his eye turned to the preacher in the Speaker’s desk, melting into tears, while the doctrine of justification by faith and salvation by grace was exhibited and vindicated against Infidel objections; was presented, as a practical subject; “a doctrine according to godliness,” and applied to the heart and conscience? This statement I make, not as showing his religious creed, for I know not what he believed on the subject; not even as proof of his being a Christian, (that proof belongs to another place.) Besides, transient emotion is not the best evidence of religious principle. But I mention the fact, merely as furnishing evidence of his sensibility – his susceptibility of tender emotion, in view of melting scenes of compassion; where justice is vindicated, while mercy is exercised; where love is exhibited, while integrity and truth are preserved; where grace is displayed, while righteousness is secured, and a holy moral government maintained; where, in a word, justice and mercy meet together, and righteousness and peace embrace each other.

Would time permit, I might here speak of his character for prudence, self-respect, industry, improvement of time, punctuality in business, early rising, exercise and general regimen; with his simplicity of manners, of dress, of equipage, of everything, indeed, becoming a true republican in a well constituted republic. For all these things were intimately connected with the development and efficient application of his intellectual powers, and his salutary influence in society.

I might too, speak of his private virtues, domestic relations, and moral character generally. But my personal acquaintance with him was not sufficiently intimate to justify the attempt to do justice to these topics. Besides, it seems uncalled for, and altogether unnecessary. For here public sentiment, I believe, universally concurs with private friendship, in pronouncing his unqualified eulogy. Here the tongue of slander is silent, and even the breath of calumny suppressed.

I might, moreover, speak more at large than I have incidentally done of his public services. But they were performed in public view, and were subjected to public inspection. They are recollected by some of my hearers; others have been told of them by their fathers; and they will soon become matters of history, and will unquestionably occupy some of the most brilliant and instructive pages of the history of liberty and our country. Let it suffice, therefore, at this time, simply to say, – No man ever served his country longer,[viii] more faithfully, with higher motives and a purer patriotism; and history will, by and by, show with better and happier ultimate results. Though party spirit has for a time counteracted some of his wise measures, and retarded the progress of improvement, it will not always retain its power; though it may, for the present, throw some obscurity over his political career, history will dissipate the darkness which surrounds it, and show it in all its brightness; will, especially, show, that the administration of the government, during his presidential term, was a model administration; among the most prudent and economical; free from the abuse of patronage, and the use of questionable power; consistent with the true spirit of the Constitution, and promotive of the cause of liberty and equal justice; – that, next to Washington, he has left the strongest impress of true republicanism on our institutions and the age. History, I say, will do him justice. Already, indeed, public opinion is returning to his rejected counsels, and preparing the way for the voice of history to be favorably heard.

But I forbear, and hasten to say a word on his crowning excellency; that which gave direction to his great talents, security to his high morals, utility to his arduous labors, and greatness to his whole character – I mean his religious principles.

Mr. Adams was a Christian; and a Christian, as has been beautifully said, “is the highest style of man.” What were his particular views on many controverted points in theology, I am not informed. He did not intrude them on the public. Indeed, I suppose though he was a close student of the Bible, he was not a technical theologian. Some of his practical sentiments come out incidentally in his published writings, but not in technical language. For example, in his second letter to his son, on the reading of the Bible, he says: “There are three points of doctrine, the belief of which form the foundation of all morality. The first is the existence of God; the second is the immortality of the soul; and the third is a future state of rewards and punishments. Suppose it possible,” he continues, “for a man to disbelieve either of these articles of faith, and that man will have no conscience; he will have no other law than that of the tiger or the shark. The laws of man may bind him in chains or put him to death, but they can never make him wise, virtuous, or happy.”

In the autumn of 1840, Mr. Adams delivered two lectures in New York, on the subject of Faith, which, at the time, made a strong impression on the public mind, and are said to have done much in arresting the progress of Infidelity. I find a synopsis of one of them in the New York Observer of November 28th, of that year, in the following words:

“1. In the existence of one Omnipresent God, the Creator of all things.

2. In the immortality of the soul, and man’s accountability to God for his conduct.

3. In the divine mission of the Lord Jesus Christ.”

But I will not detain you with farther quotations. He was a practical Christian; not a theorist; certainly not a sectarian. He called himself a Bible Christian. This blessed book he read much; and, in a course of letters to his son, written while he was in Russia, he recommends it as a Divine Revelation, to be read and studied daily, and to be made the rule of faith and practice. To enforce on his son this earnest recommendation, he says: “I have myself, for many years, made it a practice to read through the Bible once every year.” After speaking of the necessity of prayer “to Almighty God, for the aid of his Holy Spirit,” he adds: “My custom is to read four or five chapters every morning, immediately after rising from my bed.” In this daily exercise, as he stated to a friend, he used the text of the original or versions in four other languages; always, however, making use of our common English translation as one of the copies.

He was, indeed, a Bible Christian; and his letters to his son show, with what confidence and strong faith he searched the Scriptures, and submitted to their authority.

He was, too, as I said, a practical Christian. He early joined the church in his native village – a Congregational Church – formed in the days of our pilgrim fathers.[ix] Here he continued to worship and attend on the ordinances of the gospel, whenever he visited that village. At Washington, he always attended the stated service held in the Capitol in the morning, during the sessions of Congress. In the afternoon, as there were no services in the Capitol, he attended at some church in the city. He was, indeed, an example of punctuality and constancy, in attendance on the public worship and ordinances of God. I am told, that he never failed, when in health, of attending on the religious services of Congress, during the winter of 1839 and 1840. And had all the members of Congress been as constant, and punctual, and devout, as he was, I am confident, that a religious influence would have been diffused over the troubled elements of that stormy session.

Yes, he was a Bible Christian, I repeat; and a practical Christian. And this fact gave the crowning excellence to his character, and rendered him truly “a great man.”

“Know ye not,” my hearers, that “a great man is fallen?” The repetition of this inquiry brings us to the consideration of the closing scene of his life. Let us contemplate it for a few moments, as it must have appeared to those who stood around him when he fell. Truly it must have been a scene, not of excitement and solemnity merely, but of awful sublimity merely, and moral grandeur. A great man fallen, at the close of a protracted period of public service, full of years, crowned with honors, still at his post of duty, with armor on, watching for his country’s good; surrounded by his compeers; having just given his last vote, and uttered his last emphatic No in the cause of liberty; – fallen and stinking submissively into the arms of death, and even announcing his departure from earth, in language of composure and peace of mind, is indeed a scene of great moral sublimity and beauty; may I not add, in view of his Christian character and Christian hopes, and the glory and immortality which awaited him, a scene of solemn joy?

I have often stood by the bed of dying Christians – Christians, dying in peace and hope; and sometimes in the triumph of faith, and even, like Stephen, in the ecstacies of anticipated life and immortality in the presence of their God and Redeemer. And I have always viewed such scenes, not with sorrow, but with chastened joy. Indeed, it is a blessed privilege to see a Christian die. “For precious in the sight of the Lord is the death of his saints:”

The chamber, where the good man meets his fate,

Is privileged beyond the common walks

Of virtuous life – quite on the verge of heaven.

But when a great man dies, and dies in the midst of circumstances and coincidences which fill the mind with high thoughts and rich associations; which read lessons of wisdom, while they bring consolation to the living, the beauty of death swells into the sublime of immortality; the very soul of the pious spectator is lifted up, and he is ready to exclaim with Elisha, as he gazed on the ascending chariot of Elijah: “My father, my father; the chariot of Israel, and the horsemen thereof!”

Who that has faith – who that has hope, would not wish to die such a death? “Let me die the death of the righteous, and let my last end be like his!”

END.

[i] The death of Mr. Adams was, indeed, sudden; and the circumstances attending it peculiarly impressive. He had through life enjoyed almost uninterrupted health. And by his attention to diet and regimen, early rising, regularity of exercise, careful appropriation of time, and complete system in the regulation of his business and various pursuits, he had been able to accomplish more labor than most men could endure; and to accomplish it with apparent ease and satisfaction. A little more than a year before his death, he had a slight stroke of the palsy, which he viewed as the premonitory stroke of death, designed to bring his earthly labors to a close; and, we are told, he made a corresponding entry in his daily record of himself. Still, as his energies of mind remained unimpaired, and as his bodily strength and activity soon returned, he was induced to resume his public duties, and take his seat in Congress. And though he never recovered his full strength, he continued to discharge his public duties with his wonted faithfulness and punctuality; till, on Monday the 21st of February, 1848, as he sat in his seat in Congress, the same disease returned; and on Wednesday the 23d, closed his eventful life, at the ripe age of more than four-score years.

[ii] Delivered at Dudley, Mass., April 6th, 1848, being the day of the Annual Fast in this Commonwealth.

[iii] July 11, 1767.

[iv] It was stated by an intimate friend, that he continued, through life, to repeat, in connection with his evening devotions, a simple prayer, taught him by his mother.

[v] Leyden and Cambridge.

[vi] The French and German especially.

[vii] A collection of his miscellaneous publications, which, I hope, will soon be made, would furnish abundant proof of the accuracy of this general statement.

[viii] John Quincy Adams, the subject of this discourse, was born (as stated before) July 11th, 1767, in the village of Quincy, formerly a part of the town of Braintree. His ancestors were among the first settlers of that part of Massachusetts. He was the eldest son of John Adams – subsequently the second President of the United States, and Abigail (Smith) Adams, the daughter of a Congregational minister of Weymouth.

In the year 1778 – being then a lad of eleven years – he went to France with his father; and with him and at school pursued his studies as before; till, at the age of fourteen, in 1781, he proceeded to Russia, as private Secretary to Francis Dana, Minister to the Court of St. Petersburg. Thence he returned to his father, in Holland, in 1783; and with him, as Minister to the Court of St. James, he went to England, where he acted as Private Secretary to his father, (at the same steadily pursuing his classical studies) till his return to America, where he finished his classical education; and was graduated at Harvard College in 1787.

His professional studies were pursued at Newburyport, in the office of Theophilus Parsons, subsequently Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Massachusetts.

Mr. Adams commenced the practice of the law, at Boston, in 1790. But he was soon called, by President Washington, in 1794, at the early age of twenty-seven, to assume the character of a public Minister at a foreign Court; and thus he commenced that career of public service which he pursued with little interruption to the end of life.

He continued in Europe, Resident Minister, at different Courts, till he was recalled by his father, at the close of his presidential term; and returned to America in 1801.

Almost immediately on his return, he was elected a member of the Senate of Massachusetts, and, in 1803, he was appointed a Senator of the United States. This office he held till his resignation in 1808. During a part of his Senatorial term, he had held the office of Professor of Rhetoric and Oratory in Harvard College. To the duties of this office he devoted his undivided energies till 1809, when he was again called into public service, and appointed Minister Plenipotentiary at the Court of Russia. Subsequently he was called to act as one of the Commissioners in negotiating the peace of Ghent in 1815. Hence, by appointment, he proceeded to England; and became the Resident Minister of the United States, at the Court of St. James.

In 1817, he was called home to act as Secretary of State. This office he held for eight years, during both the terms of Mr. Munroe’s Presidency. In 1825, he became President of the United States. On the expiration of his presidential term, he retired to private life; till in 1831 he consented to enter Congress again, as a member of the House of Representatives. And in this capacity, he continued to serve his country, with undiminished zeal and fidelity, till Feb. 7th, 1848; when, as stated before, he died, at the age of 80 years and 7 months.

[ix] A.D., 1639.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!