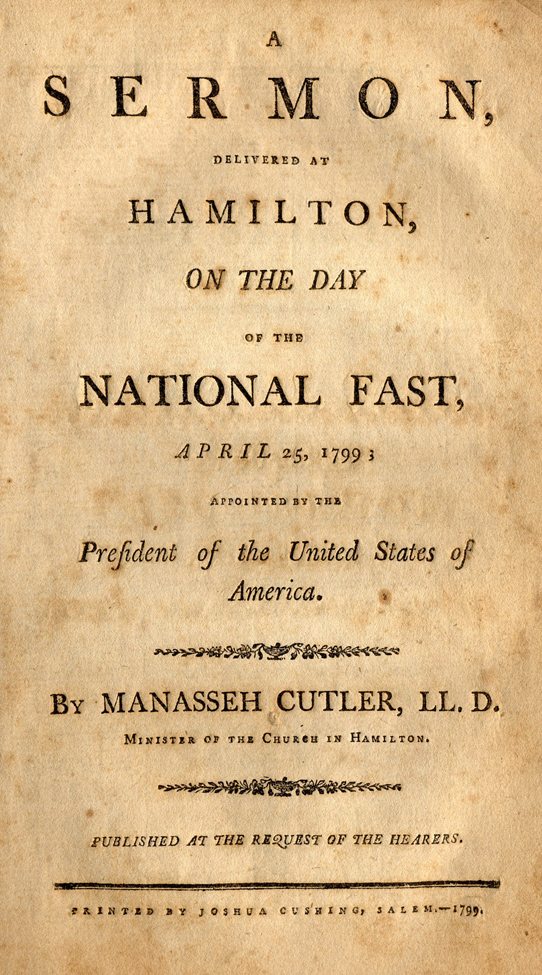

Manasseh Cutler (1742-1823) graduated from Yale (1765), and worked as a schoolteacher, store clerk, and an attorney. He was minister to the Congregational Church in Ispwich, Massachusetts (1771-1823). Cutler served as military chaplain for multiple American units during the Revolutionary War. This sermon was preached by Cutler on the day of national Fasting proclaimed by John Adams in 1799.

S E R M O N,

DELIVERED AT

H A M I L T O N,

ON THE DAY

OF THE

NATIONAL FAST,

APRIL 25, 1799;

APPOINTED BY THE

President of the United States of America.

By MANASSEH CUTLER, LL. D.

Minister of the Church in Hamilton.

A

FAST SERMON.

JEREMIAH ix. 9.

Shall I not visit them for these things? Saith the LORD:

Shall not my soul be avenged on such a nation as this?

SOLEMN were the warnings given to the Jews before they were visited with distressing judgments. But solemn as they were, they had, generally, very little effect. Some instances of reformation, however, encourage the hope, that seasonable warnings may not be in vain. In a preceding chapter the Prophet had twice addressed the Jews in the words I have now read. The repetition of the same question the third time, shews an earnest solicitude to awaken their attention. It is an appeal to their own consciences—to that faculty of the mind which is least debased. If they had any plea to make in their own behalf, if they had any reasons to offer for longer forbearance and the continuance of mercies, opportunity was given them. But so degraded was their moral character, so notorious were their ingratitude and obstinacy, they could not be insensible of it themselves. Being judges in their own cause, they must acknowledge the threatening, however severe, to be perfectly just.

Although the question is proposed to the Jews, the form of it does not permit us to confine the application to that nation. It is not said on this nation, but on such a nation as this. The alarming question must equally apply to any other nation, whose moral character resembles that of the Jews. In the preceding part of the prophecy their character is given. They are represented as a stupid, senseless, needless people. Many highly aggravated national sins are specified. Kind instructions and faithful warnings were disregarded. Neither prosperity nor adversity produced any desirable change in their obstinate temper.

At this time they seem to have been in a particular situation. The Prophet complains of a factious spirit. Treachery, discord and falsehood were prevailing vices. Principles were disseminated, and practices indulged, subversive of every religious, moral or social obligation. In their solemn meetings for religious exercises, or the administration of justice, the Prophet calls them an assembly of treacherous men. Ingenuity was employed, and the art of deception was cultivated, to overcome the natural reluctance of conscience. They bend their tongues like their bows—they teach their tongues to tell lies. Take heed, says he, every one of his neighbor, and trust ye not in any brother—they will deceive every one his neighbor—through deceit they refuse to know me, saith the Lord.

Such is the character given of Israel at the time when the Prophet addressed them in the words of the text. In the history of this nation lessons of instruction and warning are given to every nation under the sun. In the oracles of God we are furnished with a rich fund of light and truth, happily accommodated to all the variety of circumstances in which any people can be placed. There we find an admirable uniformity in the great plan of Providence, carried on by means infinitely various, and sometimes the most improbable and contradictory. To deny God’s particular providence, and the occasional exertions of his power, in an extraordinary manner, to answer extraordinary purposes, in his moral dealings with man, would be to exclude him from the immediate government of the world which he has made. Exceedingly contracted must our views be, not to perceive his superior direction—not to discern his hand in all those means which have derived their existence and their agency from him.

The occasion of our present assembling is interesting. Our Illustrious President, alarmed at the critical situation of our country, and ever watchful over its best interests, has requested the American nation to devote this day to humiliation, fasting and prayer. The sacred passage we have now before us, in its connection with the state of Israel and Judah, suggests to us subjects suited to this day’s solemnities. The question proposed in the text naturally leads to another—Is this a nation whose moral character resembles that of the Jews? It is a question that deserves serious reflection. It will direct our contemplations—to the moral state of our country—to attend to the warnings given us—and the duty of a people under our present circumstances.

In the first place we shall take a concise view of the present moral state of our country.

Like the Israelites, we are a people that have been highly favoured of the Lord. It may well be asked, What could God have done more for his vineyard? Indulgent Heaven has bestowed upon us a rich assemblage of religious, political, social and domestic blessings. The institutions of the Gospel—the means of religious instructions—the rights of conscience—the equality of all denominations of Christians—are privileges nowhere more amply enjoyed. By a wise, powerful and merciful Providence, we have been guided through perils—we have been delivered by the most unexpected means, and raised from small beginnings to national respectability and importance. Our social and domestic enjoyments, as well as national safety, are secured by a government which originated in the power of the people, and is, as near as possible, the work of each individual hand:—a government well guarded with checks, and, while the whole train of patriotic virtues are prevalent, sufficiently energetic to guaranty to every citizen the unmolested security of life and all he possesses. What returns might not be expected from such a nation as this? It is the abuse of the rich, distinguishing blessings of Heaven, which gives the proper colouring and aggravation of our national offences.

Those practices, customs and habits which are generally prevalent, are national; and such of them as are opposed to, or are inconsistent with, the will of the Deity, however made known to us, are, in the strictest propriety, the sins of a nation. Like Israel, with all our forms of piety and religion, we have been thoughtless, ungrateful and disobedient. The honour of God, and the interests of religion—objects of infinite importance to the well-being of man—have either been wholly neglected, or too generally treated with the coldest indifference. Can it be said, the true spirit of that religion to profess has been a prominent feature in our national character? Has the gospel, by its benign influence, led us to that purity of heart—to those amiable and elevated virtues—to that dignity of conduct, which raises our fallen nature to a resemblance of its Divine Author? Have we not, like the Jews, been slaves to our own corrupt affections, neglectful of our own best interests, and destroyers of our own happiness?

We have it to lament, that immoralities, of various kinds, have abounded in our land. Particular vices are always more prevalent in some parts of a country, than they are in others. Some are more fashionable at one time than at another. Vices are to be found among us of foreign importation, which, we hope, are not yet naturalized to the American soil. But in every part of our country immoralities are practiced, which, when contrasted with our distinguished advantages and blessings, sadly darken the shades of our national character, and justly provoke the divine displeasure.

The Christian Sabbath is an inestimable privilege to the church of Christ, and highly beneficial to civil society. It is the pledge of God’s distinguishing goodness to man. It was appointed for purposes the most useful and important—for keeping alive piety and devotion—for religious and virtuous instructions—and for grateful acknowledgments of the divine beneficence. But is not the design of this day shamefully perverted? Is not public worship notoriously neglected? Is not the Sabbath, to many, the most useless and burthensome day of the week? God has expressly commanded us to remember the Sabbath-day to keep it holy; and has solemnly threatened, If ye will not hearken unto me, to hallow the Sabbath-day, then will I kindle a fire in your gates, and it shall devour the palaces of Jerusalem, and it shall not be quenched.

Reverence of the Supreme Being is at the foundation of all religion. The name of God is great, admirable and holy. It ought to be used with the deepest veneration, and magnified above all things. But is it not boldly blasphemed, and impiously dishonoured?—dishonoured by customary and wanton profanity? Habits of profanity are highly injurious to society. By divesting the mind of all reverential fear of God, they lessen the solemnity and obligation of an oath. In a country where oaths are multiplied, interwoven with commercial as well as civil concerns, such habits become the more dangerous. Will the common swearer regard an oath, when administered under the most solemn forms? Is it not to be feared that perjury is among our national sins? We may, at least, adopt the language of the Prophet, and say, Because of swearing our land mourneth.

It is our happiness that the laws of our country, more, perhaps, than any other, are founded on the purest principles of religion and morality. Some of them are made for the express purpose of supporting a decent observance of the Sabbath, an attendance on public worship, and the suppression of profanity and other immoralities. Are our magistrates and civil officers sufficiently mindful of their solemn oaths, in causing a due observance of those laws?

Another evil, that may well excite serious apprehensions, is, the artful dissemination of atheistical, deistical and other loose and pernicious principles. If it can be doubted whether atheism, in its strictest sense, can become general in civilized society, it cannot be denied, that a belief in a Supreme Being may become so weakened as to lose its practical influence—that skeptical principles and sentiments subvert all religious and moral obligation, and lead to the most hardened impiety. Infidelity may be diffused under the pretext of liberality of sentiment: it may be gilded over with the specious, but perverted name of philosophy. But it requires a very small share of philosophy to know, that man is more under the influence of his feelings and passions, than his reason. Let him fully believe he is not accountable to his Maker—not destined to immortality—and what sense of moral obligation, what tie to virtue, what check upon his corrupt propensities, will there remain? What crime, when he can elude the laws of his country, will he not perpetrate? It is not possible, in the nature of things, that human laws, or principles of honour, can be adequate substitutes for religion. They are continually varying, and they will be in conformity to reigning opinions and sentiments. They may even sanction that most dangerous of all maxims, that “the end sanctifies the means.” Infidelity is a formidable enemy to the true principles of liberty. It erases from their foundation the main pillars that can support a free government. Freedom deigns not to dwell with general immorality: it cannot be enjoyed without virtue, nor an virtue be maintained without religion. Infidelity raises the floodgates of corruption—deluges society with crimes—and awfully accumulates the mass of human misery. Its prevalence is sufficient to account for the neglect of religious institutions—the violation of every sacred, civil and social duty—the practice of fraud, injustice, intemperance, debauchery, profanity, and every evil work.

In the train of vices which have stained our moral character, detraction, falsehood and discord have been too notorious to be silently passed over. The united voice of reason and divine revelation condemns them; and we find them particularly noticed by the Prophet among the national sins for which God threatened to visit the Jews. This evil spirit is not merely the disturber of domestic peace, but hostile to all the ends for which men unite in society. When discord is engendered, it makes its progress to faction, insurrection and treason, by casting reproach on rulers, and deceiving and misguiding the people. Foreign intrigue, it is well known, is the parent and the nurse of the demon of discord which troubles our nation. It has been operating by every secret art and insidious effort to weaken the powers of government. It has filled our ears with calumnies against our rulers, misrepresented public measures, excited discontent, and conjured up phantoms of despotism in the minds of the people. A people enjoying a constitution of their own forming—rulers of their own choice—and laws, as near as possible, of their own creation—who have sensibly felt the advantages of order and good government, it might reasonably be expected, would vigorously oppose attempts to disturb their political felicity. But many, it is to be feared, have, indirectly, lent their aid in lessening public confidence, in exciting opposition to government, and in bringing public measures into disrepute, without being sensible of the consequences. The maxim, which seems to have been generally adopted, that “a free people should always be jealous of their rulers,” has been carried to a dangerous extreme.

No community can enjoy the blessings of freedom unless government be respected, and the laws obeyed. In this land of liberty, public characters and public measures may, at all times, be examined with the utmost freedom. But it is only a candid, fair and upright examination that is consistent with order, moral obligation, and the true spirit of liberty. We have happily seen men placed in the highest and most responsible offices of government, who have given unequivocal proofs of their wisdom, penetration and unshaken patriotism;—men who have been instruments in procuring our numerous public blessings, and have justly merited our confidence. But with what offensive intemperance and indecency have their characters and their measures been canvassed! What numberless libels have issued from the presses against those who would guard—who would vindicate—and who would defend our country, against the intrigues, injustice and power of a despotic nation! What measures have government adopted, for our safety or defense, which have not been condemned? Who can be insensible that our freedom is in the most imminent danger, when the minority will not yield to the voice of the majority, and when party assumes the prerogative of dictating and controlling public measures. Happy would it be if the people duly appreciated the blessings of order and good government, and were disposed to pursue the means of preserving them. Let it be impressed upon our minds, that every disorganizing, demoralizing principle, and every vicious habit and practice, is hostile to freedom.

We shall only add, that deficiency in public virtue is a reproach to our nation, and endangers our safety. Nothing within the compass of human ability is so strong a safeguard to rational independence as that love to our country which is commonly styled public spirit or public virtue. Love to our country attaches us to its best interests, and elevates the mind above private advantages or selfish views. In ancient Rome this principle was the life and soul of the state. It was always awake to public danger, and active in public defense. That man is not a patriot, who prefers his own private ease and interest to the public good when his country calls for the sacrifice. Never were a people, perhaps, more devoted to the pursuits of interest, and the accumulation of wealth, than this nation. There is a laudable spirit of industry and enterprise, consistent with every public, industry and enterprise, consistent with every public, social and religious duty. But this spirit may be extended beyond the limits which bound the public safety. The public good, now, if ever, calls for the general attention, and vigilant exertion, of all its friends. Our present danger is much concealed from the public view, and on this account our state is the more hazardous. Where is the security of our possessions, when our country is infatuated by foreign intrigues, and distracted with the spirit of discord and insurrection? What value can we fix upon our wealth, when we are subjugated to the vilest, and tributary to the most tyrannic, government on earth? Our liberties are a sacred deposit, which a kind Providence has consigned to our care; and can we be so degenerate, so base, as to desert or give it up? If we are deaf to the calls of public safety, liberty and virtue, we are traitors to our country, we are criminal in the sight of Heaven, and deserve its chastisements.

In this concise view, we have only a faint sketch of our moral state. It ought to be recollected that the sin of a nation is the aggregate of the sins of all who reside in it. No individual can exculpate himself from the charge of having contributed a part in swelling the measure of our national iniquities; and all must expect to be sharers in public calamity. Whatever we may vainly think of our own state, however we may be lulled by a fatal security, it must be acknowledged, that great and manifold are our errors, and heavy and numerous are our transgressions. Were we able to bring into view the whole mass of wickedness that has been accumulated in our land, exceeding all the rules and powers of arithmetical computation, can we wonder if God should avenge himself of such a nation as this? But his ways are not as our ways, nor are his thoughts like ours. His threatenings are intended to awaken our attention. His merciful admonitions are accompanied with sufficient opportunity for repentance and amendment.

We therefore proceed, as was proposed, in the second place, to attend to the warnings which are given us.

We learn from the sacred scriptures, and from general history, the usual methods of Providence, in the government of the world. There seems to have been no period of time, when general and distressing calamities came upon a people without previous warning. The deluge came not upon the earth, until Noah, a preacher of righteousness, had, for a course of years, warned that corrupt generation of approaching ruin. Sodom and Gomorrah were not reduced to ashes, before they had been faithfully admonished by Lot, whose soul was vexed by their corrupt deeds. Pharaoh and the Egyptians were visited with a series of milder judgments, as so many kind admonitions, before their final overthrow. Jonah was sent, as the messenger of Heaven, to denounce against Nineveh its total destruction. Happily for this city, its inhabitants, from the king on the throne to the beggar in the streets, were awakened to a sense of their danger and their duty. Although an heathen people, they humbled themselves before the most high God, and were graciously spared. The history of Israel furnishes us with numerous instances of faithful admonitions given to them, and of the most persuasive entreaties to escape from impending judgments by turning unto the Lord. Our Saviour himself was the benevolent monitor to Jerusalem, before its final destruction. While he foretold that awful catastrophe, which would be more distressing than had been known from the creation, he entreated them, in the most tender and pathetic strains, to have mercy upon themselves. The sacred scriptures are a standing memento to us, under all the aspects of Divine Providence. The apostle, after mentioning what had been the conduct of the Jews, and the divine dispensations towards them, in a number of instances, adds, Now all these things happened unto them for ensamples: and they are written for our instruction, upon whom the ends of the world are come.

Other nations, besides the Jews, exhibit to us the most solemn admonitions. We have interesting lessons for our instruction in the revolutions which have desolated so many independent states in Europe. We have seen their errors and their fate, and we should avoid the rock on which they have been broken and ruined. In many interesting particulars, we read our own history in theirs.

Holland was the first that fell a prey to the intriguing arts of French revolutionists. The people, allured by the salacious hope of mending their government—seduced by solemn treaties—and flattered with the promise of assistance and protection—admitted the armies of their pretended ally into their cities. Their government was new modeled by the French Directory, and subjected to its absolute control. Heavy contributions were exacted, which have since been frequently repeated, and the immediate collection ensured by an armed force. The treasures, the magazines, the naval and military forces, of Holland, fell within the grasp, and became subject to the requisitions, of the French government of their own, the rich, frugal, industrious people of Holland now groan under the most tyrannic oppression. They are obliged to support, in their own bosom, an army of Frenchmen, to keep themselves is awe.

Geneva, a little happy republic, which had long viewed France as her friend, has suffered a more deplorable fate. The people were pleased with their government, were flourishing in manufactures and commerce, and were distinguished for their religion and good morals. The government of Geneva made every exertion to maintain a scrupulous neutrality, through a strong party, by “diplomatic skill,” was gained over to the French interest. Emissaries were sent to excite a spirit of faction, and to corrupt the morals of the people. These harbingers of ruin too well succeeded. Divisions, tumults and massacres were the fruit of their exertions. At length, when the favourable moment arrived, an army approached, and, by insidious arts, found means to enter the city. The eyes of the people were now opened, but I was too late. The united, fought, bled, and were conquered. Geneva surrendered at discretion—was pillaged by a merciless soldiery, and degraded to a humble department of France.

Another victim to the secret arts and duplicity of France, is the ancient republic of Venice. Under a government of wise laws, the republic abounded in commerce and wealth. The French resorted to their usual intrigues, which had never failed of success; but they were greatly counteracted by a wise and discreet Senate. Impatient to seize upon the wealth of Venice, they wished to find some pretext for open hostilities. This they found in a stratagem, which, one would think, none but a Frenchman could have devised. 1 Venice was attacked, conquered, partitioned, bartered and sold. It is with the fate of this devoted republic that France has threatened the American States.

The time will not permit us to notice all the governments which have felt the scourge of the French revolutionary pestilence. It would fill volumes to detail the general wreck of order, the scenes of slaughter, plunder, conflagration, distress, and ruin, which the French, by their intrigues, arms and usurpation, have spread over the fairest parts of Europe. In Suabia, from well attested accounts, the progress of their armies was marked by crimes at which humanity shudders—crimes, which savages were never known to commit. The common people were ready to receive them with open arms, and to embrace them as their friends and deliverers; but they found them the most detestable monsters. 2

We must not pass over the fate of unhappy Switzerland. This country in many respects resembled our own. It gives us warning, so solemn, so well adapted, that Americans must be inexcusable not to improve it to their own advantage. The Republic of Switzerland consisted of twenty smaller republics in federal union. Common interest and long experience had strengthened the ties of a formal league, and closely cemented them together. It was a nation of warriors and statesmen—of frugal, hardy, industrious citizens;—a nation jealous of its rights, and watchful over its liberties. While the torch of revolutionary fanaticism was flaming around them, the government, aware of its dangers, made every exertion, and every sacrifice, to preserve an unblamable neutrality. The emissaries of France had not been able to do so much in deluding the people, as they had done in many other places; but with the government they had better success. Their councils were divided and indecisive. Every measure for the public safety was opposed and embarrassed. Little was done in making arrangements for defense, until a French army was upon their borders. The people, more alarmed, and better united, than their rulers, flew to arms, and determined to defend a government that had not the spirit to defend itself. A few veteran officers placed themselves at their head; but orders and counter orders defeated their best plans of operation. Obstinate battles were repeatedly fought, with great slaughter and various success. Such was the general enthusiasm, that the women repaired to the field of battle, and fought and bled by the sides of their husbands and sons. 3 At this moment, the French, with an address peculiar to themselves, renewed a mock negotiation, made and violated solemn agreements, and found means to make the people believe their own civil and military officers had betrayed and sold them. This last artifice, more than any other, proved fatal to Switzerland. The cry of treachery, in their camps and among the people, excited a general ferment of distrust and dissension. Some of the bravest of the Swiss officers fell victims to the rage of their own men. Unable to repel an enemy, more formidable in artifices than in arms, the greater part of that once happy country was ravaged. Murder, rapine, pillage and desolation marked the footsteps of its conquerors. The ancient government of Switzerland was dissolved, and a new constitution, fabricated by the French Directory, imposed on the people. In eight days was overturned the work of five centuries. What scenes of misery have the French revolution, perfidy and arms exhibited! What stately edifices of political society have been laid in ruins! Vice has been armed against virtue. The warmest professions of friendship have been accompanied with the practice of the most savage cruelty. France has demonstrated to the world, that its sole object is plunder and tribute, and that it regards not the means by which it can be attained.

Such are the beacons erected in Europe, to caution and warn Americans. Can we stop our ears against the cries of these desolated republics? Can we be deaf to a voice, like peals of thunder, charging us to beware of the perfidy of France?

We shall, then, in the last place, turn our attention to our own duty, at a crisis so important as the present.

It is our duty, attentively to consider the dangers that threaten us. I wish not to excite groundless apprehensions; but to me it appears, that the situation of our country was never more hazardous, and that the great body of the people are too insensible of it. Dangers, concealed from the public view, will not impress the public mind. They resemble a disease upon the vital parts, which excites no alarm, till it is too late for a cure. Were armies marching to invade our country, or ships of war approaching our shores, the people would be alarmed—-the true American spirit would be roused—and the united efforts of our citizens, under the favour of Heaven, might bid defiance to the powers of Europe. But the enemy, with whom we have to contend, is carrying on a different mode of warfare. She is pursuing her hostile designs, not by a manly, open declaration of war, but by salacious pretensions of friendship—not by attacking us with fleets and armies, but by her “diplomatic skill,” by every species of deception, and by making our own citizens the instruments of their country’s ruin.

To meet the dangers that threaten us, it is our duty to be firm, united, and faithful to our country. France has told us the humiliating truth, that we are “a divided people;” and she is determined to profit by the spirit of discord she has found means to diffuse among us. Every artifice is employed, every engine is at work, probably with more system than ever, to strengthen the party her influence has created. The increase of public expenses, the burthen of taxes, the establishment of a navy, and raising an army, are topics well adapted to excite uneasiness among the people. It is true, our national expenses are great, and must probably be still increased. But, what!—is not our independence and property worth defending? Can we hesitate a moment at the burthen of expenses, when they may be the price of the ransom of our liberties? Why have we been at the expense of so much treasure and blood to obtain our freedom, if we intend not to maintain it? Can Americans be so debased, as to be dupes to any foreign government? Can they suffer themselves to be crushed, and ruined, without making every exertion in their own defense? Can they admit the thought, even for a moment, of submission to an ignominious tribute, which can be limited by nothing but the rapacity of their masters, and their own utmost ability to pay? Let those who complain of the increase of taxes and expenses, consider from what cause they have arisen. Had Americans unitedly and firmly attached themselves to their own government—had France been unable to gain over a party, would she, as she has done, have preyed upon our commerce, and risked the loss of supplies from our country? It is not to our own government, but to the party opposed to it, that we are to charge our burdens, depredations and dangers.

Another artifice is, the cry that our own government is for war, while France wishes for peace. Although the falsity of this cry has been proved by a glare of evidence, it is still continued. The measures of our own government, and the conduct of the French, have given the fullest proof, that an honourable or a safe peace has not been attainable. Peace we most ardently desire; but not upon terms more dangerous to our liberties, more destructive to ourselves, than war. Besides, were the most flattering terms to be offered, what dependence could we place on a government of atheists, constantly acting in conformity to their principles? What solemn contract have the Directory respected, any further than they found it convenient for themselves? What man in his senses would depend upon a contract with a burglar or highway robber not to injure him? When a government sports with natural justice, national laws and usages, which a savage would hold sacred, it forfeits every claim to confidence. It is ardently to be hoped that America will never form an alliance with the present government of France.

It is now evident, if the measures which the French party would have dictated to our government had been adopted, that, long before this time, the yoke which France has been preparing would have been fastened upon our necks. To the wisdom, firmness and patriotism of our government, under Providence, we owe the freedom we this day enjoy. Every man that feels as every American ought to feel, will confess that measures for national defense were indispensable. The protection already given to our commerce we have seen to be highly beneficial. What immense property has been heretofore lost for the want of it; and what would the state of our trade now have been, if no protection had been afforded! The laborious farmer, the industrious mechanic, as well as the adventurous merchant, are sharers in the benefits of a prosperous commerce.

Leaving the administration of government to the wisdom of those in whose hands the people have placed it, every true friend to his country will cheerfully contribute his part to defend and support it. To withhold that portion of our property which the public safety requires, is cheating ourselves. The first establishment of a direct national tax must be attended with great expense, difficulty and inequality. Can it be imagined that Congress, who had the best means of information, and must pay their proportion, did not adopt the best mode their wisdom could devise? The spirit of faction and insurrection has already cost us millions;—and is it still to be cherished? It is a happiness to know, that I am addressing an assembly so entirely united in their general ideas of public men, and public measures, and steadily opposed to a spirit of faction. But you have need to be upon your guard, left this evil spirit should make you a visit. Let one common cause, one common interest, and one common danger, keep us united. Following the guidance of Heaven, and attentive to all the means in our power, let it appear that we have not lost that noble, determined spirit, which gained our independence.

Further, it is especially our duty to attend to our moral character. When we seriously reflect on the moral and political state of our country, we must be sensible that our offences are great and manifold, and that God, in his righteous displeasure, is visiting us for our national sins. Penitent confession, humble prayer, and sincere and effectual purposes of amendment, are indispensable duties on this day. And it is only in the right discharge of these duties that we have ground to hope, that God, in the rain of his providence, will remove the evils we feel, and avert those we fear. Happy would it be, if a general spirit of repentance and reformation were to spread throughout our land. We have individually added to the mass of national iniquity: it therefore concerns us, individually, to be humble, and to reform what is amiss in ourselves. As in the day of battle, every man should behave as if on his single arm depended the victory, so let every one feel as if on his piety and virtue depended the salvation of his country.

It should be our concern to arrest the progress of infidelity and irreligion, by living like Christians ourselves. The most effectual method, perhaps, to prevent the spreading of loose, pernicious, demoralizing sentiments, is to put them out of countenance by our own conformity to the spirit of sincere, practical religion. If we truly embrace he doctrines, and conform to the precepts, of the gospel of Christ, the benign influence of this Heaven-born religion over all the affairs of human society, and all the concerns of man, will be apparent. Example may do more to confute gainsayers, than a thousand opposing arguments. Let the fool say in his heart, There is no God. Let the infidel glory in mere hypothesis, and depend upon artificial conjecture: it is all he can produce in support of his principles. The believer finds himself upon a foundation that cannot be moved. God is the rock of ages. The dictates of common sense teach him, that God is to be seen in everything around him, heard in the voice of every creature, felt in every motion, and read in every page of the book of nature. The good man finds infinitely more satisfaction, in believing in the perfections of the Deity, the wisdom and equity of Providence, and the great plan of redeeming mercy, than all the systems of philosophic infidelity are capable of yielding. The infidel lays the axe to the root of the tree, and cuts down with one stroke the hope and confidence of man. But the believer has a fortress in every danger; a refuge in every storm; an abiding friend in all the vicissitudes of human life; and a safe conductor to eternal rest.

It cannot be too deeply impressed upon our minds, that without public and private virtue, a free government cannot be supported. The Creator and Governor of the Universe is, and was, and ever will be, the supporter of order and virtue. The Christian religion is, in the highest degree, friendly to rational liberty. It teaches a proper conduct in all the relations we sustain in society. The origin of all society is in our families. They are the nurseries from which every citizen in the state is transplanted. In them the foundation of order and good government should be laid. By daily attention to the scriptures and family devotion, by training up our families in a religious observance of the Christian Sabbath, and in attending on public worship, we take the most direct methods to qualify them for good citizens, and to give an early check to all those vices which are ruinous to society.

When religion and virtue are urged as the main pillars of national freedom and prosperity, will it be said that France is an exception?—that with all her atheism, corruption and crimes, she is prosperous?—that her government is supported?—that victory attends her arms?—and that her wealth is accumulating by piracy and plunder? If so, it may be answered, that freedom is not to be found in the present government of France. A military government requires neither religion, nor virtue. By renouncing all religion she is making an experiment, which is not yet come to a result. It is such an experiment as the world has never before seen, and may, in the event, throw more light upon the real state of man, in his social relations, than all the disquisitions that have ever been written. Vice has often been permitted to prosper for a time; but the end has been ruin. The ways of Providence are intricate. The vilest of men have been, and may be, employed as instruments in the accomplishment of the wisest and most benevolent purposes. The Almighty said to Sennacherib, O Assyrian, the rod of mine anger, and the staff in their hand, is mine indignation. I will send him against an hypocritical nation; and against the people of my wrath will I give him a charge to take the spoil, and to take the prey, and to tread them down like the mire of the streets. It is added, Howbeit he meaneth not so, neither doth his heart think so. But it is in his heart to destroy and cut off nations not a few. 4

We shall only add, that, at a time like this, it concerns us to be deeply sensible of our dependence upon Heaven. It is our duty to look through all means and instruments—all the relations of causes and effects, to Him who is the Supreme Ruler and Judge among the nations; and to place our dependence on that Being, who is able to save, or destroy. In vain shall we confide in political expedients without his concurrence and blessing. If infidelity, irreligion, discord and faction should increase and abound, must we not expect that God will visit, and will avenge himself on such a nation as this? But if the professed designs of this day’s solemnityies should meet his benediction and acceptance; if a sense of our national offences, and the warnings given us by his word and providences, should lead us to a proper temper and conduct; if the numerous blessings we enjoy should excite in our minds sincere gratitude; if, by piety and prayer—by a continual concern to practice that righteousness, and those patriotic virtues, which exalt a nation; and if by a studious care to put away that sin which is a reproach to a people, we place our dependence upon Heaven, then may we hope to enjoy all those natural, civil and religious privileges and advantages, for which our country has been distinguished. Then, indeed, may we be assured that God will visit us, not in judgment, but with the desirable blessings of national protection, peace and prosperity. May God, of his infinite mercy, through the Mediator, make this the happy state of our country; and to him be glory forever.

AMEN.

Endnotes

1. “The destruction of Venice was determined on. This republic had a wise government, good laws, and great wealth. But Venice had observed so scrupulous a neutrality, with respect to this dangerous neighbor; its senate had conducted itself so uprightly and irreproachably, that the Directory had not the least grounds for a declaration of war. It was therefore obliged to have recourse to trick, and to form this stratagem:

“A dozen officers, clothed as citizens, were ordered to repair to Venice, and to assassinate some of the French soldiers whom the Venetian government had kindly admitted into the city hospitals. The officers obeyed their orders precisely. About disk they poignarded four or five of their countrymen, and immediately returned to camp, with the alarming intelligence that the Venetians were massacring the French republicans, and on the following day Venice was no more. In the course of a few hours it was converted into a theatre of carnage and proscriptions, and delivered up to be pillaged by the soldiery. This was the real cause of, or rather pretext for, the destruction of a republic, flourishing in laws, in commerce and wealth.”

Extract of a letter written by a gentleman in Paris.

2. “The village of Bremen, on the 6th of October, was beset by a band of robbers, under the denomination of republican soldiers, who, mad with wine, rushed into the houses with the most hideous war-whoops, and had immediate recourse to their well known system of plunder. All the coffers and closets were broken open and rifled—all the household furniture was destroyed—the peasants were required, with loaded pistols at their breasts, to deliver up their money—the beds and bedding were unripped and examined—and, under pretence of searching for concealed treasure, not only the floors of the rooms were torn up, but even infants were vehemently dragged from their cradles, and many families were deprived of nearly all their property. But still more terrible to these peaceable and innocent country people was the infernal manner in which the female sex was treated by these villains. In the whole village there was neither maiden, wife, nor widow, who was not forcibly and repeatedly dishonoured; and such was the depravity of these miscreants, that eight, ten, and frequently more than that number, successively insulted the same unfortunate victim, with the accomplishment of their brutal purposes. Neither early youth, nor hoary-headed age, nor deformity, nor yet the most offensive disorders, could abate the fury of their passions; and not only husbands, but fathers and children, were made to be witnesses of these abominable outrages”

Cannibal’s Progress, by Anthony Ausrer, Esquire.

The above is only a specimen of the general conduct of the French army in passing through the whole circle of Suabia. It was nearly the same in every place. This and a copious number of similar facts were taken by the magistrates, and are published under the sanction of their authority. All their outrages were in violation of a solemn contract. The circle of Suabia entered into an agreement with the French General, Moreau, to pay the enormous tribute of about 8 millions of dollars, which they punctually performed, on condition “that the persons and property of the inhabitants should be strictly respected.”

3. The environs of Berne, eight hundred women took up arms, and joined the last battle. At Frauenbrun, two hundred and sixty women and girls received the enemy with scythes, pitchforks and axies; an hundred and eighty were killed; among them was one named Glar, who had at her side two daughters and three grand-daughters, the youngest scarcely 10 years old: these six heroines were slain.”

J. Mallet Du Pan’s Hist. of the destruction of the Helvetic Union and Liberty. This Book ought to be read by every American.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!