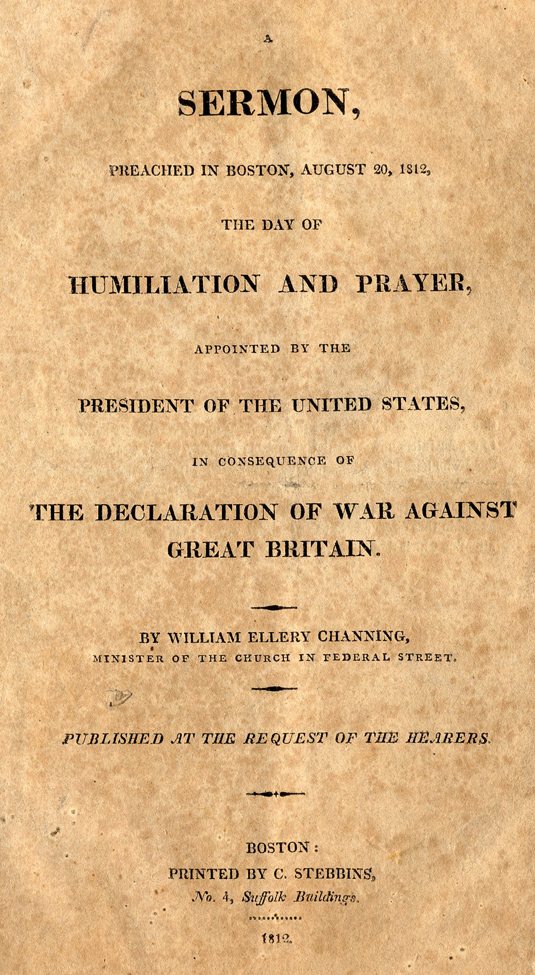

William Ellery Channing1 (1780-1842) was the grandson of one of the Newport Sons of Liberty, John Channing. William graduated from Harvard in 1798 and became regent at Harvard in 1801. He was ordained a preacher in 1802 and worked towards the 1816 establishment of the Harvard Divinity School. This sermon was preached by Channing on the national fast day proclaimed by President James Madison2 for August 20, 1812.

A

SERMON,

PREACHED IN BOSTON, AUGUST 20, 1812,

THE DAY OF

HUMILIATION AND PRAYER,

APPOINTED BY THE

PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES,

IN CONSEQUENCE OF

THE DECLARATION OF WAR AGAINST GREAT BRITAIN

BY WILLIAM ELLERY CHANNING,

MINISTER OF THE CHURCH IN FEDERAL STREET,

THE author is not insensible to the many imperfections of this discourse, and he laments that his engagements have not permitted him to render it less unworthy the favourable opinion, which was expressed by those who heard it. He has consented to publish it, because he considers it closely connected with his late Fast Sermon3, and because he wishes to express with greater precision some important sentiments, which were suggested in that discourse, but to which he was not able to give the time and attention which they deserve.

ACTS XXIV. 16.Herein do I exercise myself, to have always a conscience void of offence toward God and toward man.

A CONSCIENCE void of offence is an inestimable blessing. We need it in prosperity—for no condition however prosperous can give happiness, if our own hearts reproach us, if remorse mingle itself with our recollections of the past, and the dread of retribution with our anticipations of futurity. We peculiarly need it in adverse and perilous times—for it has power to impart serenity, firmness, and hope, when every outward event conspires to depress and overwhelm us. In periods of public calamity, happy is that man, whose conscience approves him, who carries with him the supporting reflection, that he has been faithful in the sphere assigned him by Providence; that he has labored, according to his power, to avert the ruin, which threatens his country; that he has not hastened or aggravated national suffering, by abusing the rights of a citizen, or violating the duties of a man and a Christian. To aid you in securing to yourselves, this support and consolation, I propose to point out to you some of the duties, which belong to the period, in which we live, particularly those duties, which grow out of our relations to our rulers and our country. My views of our political state, and of the war, in which we are engaged, I have lately unfolded, and shall not now repeat them. The question is, what conduct belongs to a good citizen, in our present trying condition.

Our condition induces me to begin, with urging on you the important duty of cherishing respect for civil government, and a spirit of obedience to the laws. I am sensible, that many whom I address consider themselves called to oppose the measures of our present rulers. Let this opposition breathe nothing of insubordination, impatience of authority, or love of change. It becomes you to remember, that government is one of the noblest and most valuable of human institutions—essential to the improvement of our nature—the spring of industry and enterprise—the shield of property and life—the refuge of the weak and oppressed. It is to the security which laws afford, that we owe the successful application of human powers—the progress of the useful and elegant arts—the splendor of the city—and the beauties of the cultivated field. Government, I know, has often been perverted by ambition and other selfish passions; but it still holds a distinguished rank among those institutions, by which man has been rescued from barbarism, and conducted through the ruder stages of society, to the habits of order, the diversified employments and dependences, the refined and softened manners, the intellectual, moral and religious improvements of the age in which we live. We are bound to respect government, as the foundation of the social edifice—the great security for social happiness; and we should carefully cherish that habit of obedience to the laws, without which the ends of government cannot be accomplished. All wanton opposition to the constituted authorities; all censures of rulers, originating in a factious, aspiring, or envious spirit; all unwillingness to submit to laws, which are directed to the welfare of the community, should be rebuked and repressed by the frown of public indignation.

It is impossible, that all the regulations of the wisest government should equally benefit every individual of the society; and sometimes the general good will demand arrangements, which will interfere with the interests of particular members, or classes of the nation. In such circumstances, the individual is bound to regard the inconveniences under which he suffers, as inseparable from a social, connected state; as the result of the condition, which God has appointed; and not as the fault of his rulers; and he should cheerfully submit, recollecting how much more he receives from the community, than he is called to resign to it. Disaffection towards a government, which is administered with a view to the general welfare, is a great crime; and such opposition, even to a bad government, as infuses into subjects a restless temper, an unwillingness to yield to wholesome and necessary restraint, deserves no better name. In proportion as a people want a conscientious regard to the laws, and are prepared to evade them by fraud, or to arrest their operation by violence; in that proportion they need and deserve an arbitrary government, strong enough to crush at a blow every symptom of opposition.

These general remarks on the duty of submission are by no means designed to teach, that rulers are never to be opposed. Because I wish to guard you against that turbulent and discontented spirit, which precipitates free communities into anarchy, and thus prepares them for chains, you will not consider me as asserting, that all opposition to government, whatever be the occasion, or whatever the form, is to be branded as a crime. Subjects have rights as well as duties. Government is instituted for one and a single end,—the benefit of the governed; the protection, peace, and welfare of society; and when it is perverted to other objects, to purposes of avarice, ambition, or party spirit, we are authorized and even bound to make such opposition, as is suited to restore it to its proper end, to render it as pure as the imperfection of our nature and state will admit.

The Scriptures have sometimes been thought to enjoin an unqualified, unlimited subjection to the “higher powers;” but if we attend, we shall see that the injunction is founded on the principle, that these powers are “ministers of God for good,” are a terror to evil doers, and an encouragement to those that do well. When a government wants this character, when it becomes an engine of oppression, the scriptures enjoin subjection no longer. Expedience may make it our duty to obey, but the government has lost its rights; it can no longer urge its claims as an ordinance of God.

There have, indeed, been times, when sovereigns have demanded subjection as an unalienable right, and when the superstition of subjects has surrounded them with a mysterious sanctity, with a majesty approaching the divine. But these days have past. Under the robe of office, we, my hearers, have learned to see a man, like ourselves; invested with dignity for the benefit of his fellows; most honourable, most worthy our reverence, when, in the spirit of the universal sovereign, he employs power to execute justice and dispense blessings; and most degraded and worthless amidst all his pomp, when he forgets that his power is a trust, and prostitutes it to selfish ends. There is no such sacredness in rulers, as forbids scrutiny into their motives, or condemnation of their conduct. If indeed elevation of rank gave elevation to the character, implicit confidence in government would be our duty. But, rulers, when they leave the common walks of life, leave none of their imperfections behind them. Power has even a tendency to corrupt—to feed an irregular ambition—to harden the heart against the claims and sufferings of mankind. Rulers have generally seemed to be raised too high for sympathy, and have often sported with human rights and happiness, for the purpose of extending, or displaying their power. Rulers are not to be viewed with a malignant jealousy; but they ought to be inspected with a watchful, undazzled eye. Their virtues and services are to be rewarded with generous praise; and their crimes, and arts, and usurpations should be exposed with a fearless sincerity, to the indignation of an injured people. We are not to be factious, and neither are we to be servile. With a sincere disposition to obey, should be united a firm purpose not to be oppressed.

So far is an existing government from being clothed with an inviolable sanctity, that subjects, in particular circumstances, acquire the right, not only of remonstrating, but of employing force for its destruction. This right accrues to subjects, when a government wantonly disregards the ends of social union; when it threatens the subversion of national liberty and happiness; when it makes encroachments which, if endured, will lead to the prostration of all the rights of a people; and when no relief but force remains to the suffering community. This however is a right which cannot be exercised with too much deliberation. Subjects should very slowly yield to the conviction, that rulers have that settled hostility to their interests, which authorizes violence. They must not indulge a spirit of complaint, and suffer their passions to pronounce on their wrongs. They must remember, that the best government will partake the imperfection of all human institutions, and that if the ends of the social compact are in any tolerable degree accomplished, they will be mad indeed to hazard the blessings they possess, for the possibility of greater good. They should weigh, not only the evils they suffer, but the evils of resistance; the tumultuous state in which an appeal to force may leave them; the danger of dissolving instead of improving society. They should anxiously inquire, if no methods, more peaceful, will bring them relief.

It becomes us to rejoice, my friends, that we live under a constitution, one great design of which is—to prevent the necessity of appealing to force—to give the people an opportunity of removing, without violence, those rulers from whom they suffer, or apprehend an invasion of rights. This is one of the principal advantages of a republic over an absolute government. In a despotism, there is no remedy for oppression but force. The subject cannot influence public affairs, but by convulsing the state. With us, rulers may be changed, without the horrors of a revolution. A republican government secures to its subjects this immense privilege, by confirming to them two most important rights; the right of suffrage, and the right of discussing with freedom the conduct of rulers. The value of these rights in affording a peaceful method of redressing public grievances cannot be expressed, and the duty of maintaining them, of never surrendering them, cannot be too strongly urged: resign either of these, and no way of escape from oppression will be left you, but civil commotion.

From the important place which these rights hold in a republican government, you should consider yourselves bound to support every citizen in the lawful exercise of them, especially when an attempt is made to wrest them from any by violent means. At the present time, it is particularly your duty to guard, with jealousy, the right of expressing with freedom your honest convictions respecting the measures of your rulers. Without this, the right of election is not worth possessing. If public abuses may not be exposed, their authors will never be driven from power. Freedom of opinion, of speech, and of the press, is our most valuable privilege—the very soul of republican institutions—the safeguard of all other rights. We may learn its value if we reflect, that there is nothing which tyrants so much dread. They anxiously fetter the press, they scatter spies through society, that the murmurs, anguish, and indignation of their oppressed subjects may be smothered in their own breasts; that no generous sentiment may be nourished by sympathy and mutual confidence. Nothing awakens and improves men so much as free communication of thoughts and feelings. Nothing can give to public sentiment that correctness, which is essential to the prosperity of a commonwealth, but the free circulation of truth, from the lips and pens of the wise and good. If such men abandon the right of free discussion—if, awed by threats, they suppress their convictions—if rulers succeed in silencing every voice, but that which approves them—if nothing reaches the people, but what will lend support to men in power—farewell to liberty. The form of a free government may remain, but the life, the soul, the substance is fled.

If these remarks be just, nothing ought to excite greater indignation and alarm, than the attempts, which have lately been made to destroy the freedom of the press. We have lived to hear the strange doctrine, that to expose the measures of rulers is treason; and we have lived to see this doctrine carried into practice. We have seen a savage populace excited and let loose on men, whose crime consisted in bearing testimony against the present war; and let loose, not merely to waste their property, but to shed their blood, to tear them from the refuge which the magistrate had afforded, to slaughter them with every circumstance of cruelty and ignominy. I do not intend to describe that night of horrors, to show to you citizens, who had fought the battles of their country, beaten to the earth, trodden under foot, mangled, dishonoured!—What ought to alarm us even more than this dreadful scene is, the disposition which has been discovered to extenuate these atrocities, to speak of this bloody outrage as a mode of punishment, irregular indeed, yet mitigated by the guilt of those who presumed to arraign their rulers. In this and in other language, there have been symptoms of a purpose, to terrify into silence those, who disapprove the calamitous war, under which we suffer; to deprive us of the only method, which is left, of obtaining a wiser and better government. The cry has been, that war is declared, and all opposition should therefore be hushed. A sentiment more unworthy of a free country can hardly be propagated. If this doctrine be admitted, rulers have only to declare war and, they are screened at once from scrutiny. At the very time when they have armies at command, when their patronage is most extended, and their power most formidable, not a word of warning, of censure, of alarm must be heard. The press, which is to expose inferior abuses, must not utter one rebuke, one indignant complaint, although our best interests, and most valuable rights are put to hazard, by an unnecessary war. Admit this doctrine, let rulers once know that by placing the country in a state of war, they place themselves beyond the only power they dread, the power of free discussion, and we may expect war without end. Our peace and all our interests require, that a different sentiment prevail. We should make our present and all future rulers feel, that there is no measure, for which they must render so solemn an account to their constituents, as for a declaration of war; that no measure will be so freely, so fully discussed; and that no administration can succeed, in persuading this people to exhaust their treasure and blood in supporting war, unless it be palpably necessary and just. In war then, as in peace, assert the freedom of speech and of the press. Cling to this, as the bulwark of all your rights and privileges.

But, my friends, I should not be faithful, were I only to call you to hold fast this freedom. I would still more earnestly exhort you not to abuse it. Its abuse may be as fatal to our country as its relinquishment. Every blessing may, by perversion, be changed into a curse, and this is peculiarly true of the press. If undirected, unrestrained by principle, the press, instead of enlightening, depraves the public mind; and, by its licentiousness, forges chains for itself and for the community. The right of free discussion is not the right of saying what we please, what our passions prompt; not the right of diffusing falsehood and evil principles.—Nothing is to be spoken or written but the truth, and truth is so to be expressed, that the bad passions of the community shall not be called forth, or at least shall not be unnecessarily excited. From what wretchedness would our country be saved, were these simple rules observed. On political subjects, there is less regard to truth, more of false colouring and exaggeration, than on any other. The influence of the press is very much diminished by its gross and frequent misrepresentations. Each party listens with distrust to the statements of the other and the consequence is, that the progress of truth is slow, and sometimes wholly obstructed. Whilst we encourage the free expression of opinion, let us unite in fixing the brand if infamy on falsehood and slander, wherever they originate; whatever be the cause they are designed to maintain.

But it is not enough that truth be told. It should be told for a good end; not to irritate but to convince; not to inflame the bad passions, but to sway the judgment and to awaken sentiments of patriotism. In this country, political discussion has decidedly an unhappy influence on the temper. Many talk and write for the simple purpose of wounding their opponents. There are, comparatively, few attempts to mollify. Those who have embraced error are confirmed, hardened in their principles, by the reproachful epithets, which are heaped upon them by their adversaries. I do not mean by this, that political discussion is to be conducted with a frigid tameness, that no sensibility is to be expressed, no indignation to be poured forth on wicked men and wicked deeds. But this I mean, that we should deliberately inquire, whether indignation be deserved, before we express it; and the object of expressing it should ever be, not to infuse ill-will, rancor, and fury into the minds of men, but to excite an enlightened and conscientious opposition to injurious measures. He who addresses his fellow citizens on political topics, should ever propose to impart correct principles, and to awaken pure and honourable feelings; and the press, when employed for other ends, is grossly perverted.

Every good man must mourn, that so much is continually spoken, written and published among us, for no other apparent end, than to gratify the malevolence of one party, by wounding the feelings of the opposite. The consequence is, that an alarming degree of irritation exists in our country. Fellow citizens burn with mutual hatred, and some are evidently ripe for outrage and violence. In this feverish state of the public mind, we are not to relinquish free discussion, but every man should feel the duty of speaking and writing with deliberation. It is the time to be firm without passion. No menace should be employed to provoke opponents—no defiance hurled—no language used which will, in any measure, justify he ferocious in appealing to force.

By this language I do not mean to suggest, that I anticipate scenes of violence and murder, such as have lately been exhibited in other parts of our land, as have made our hearts thrill with grief, indignation, and horror. I have too much confidence in the good principles and habits of this section of our country. I trust, that none of us shall live, to hear the yell of a murderous mob ringing through our city, to see our streets flowing with the blood of citizens, butchered by the hand of citizens. But, my friends, there is a violence in the passions of this community, which ought to give us some alarm; which ought to set us all on our guard, lest, by our rashness, and intemperate language, we gradually lead on to a tremendous convulsion.

The sum of my remarks is this. It is your duty to hold fast and to assert with firmness those truths and principles on which the welfare of your country seems to depend; but do this with calmness, with a love of peace, without ill will and revenge. Improve every opportunity of allaying animosities. Strive to make converts of those whom you think in error: do not address them, as if you wished to make them bitter enemies to yourselves and your cause. Discourage in decided and open language, tat rancor, malignity, and unfeeling abuse, which so often find their way into our public prints, and which only tend to increase the already alarming irritation of our country. Remember, that in proportion as a people become enslaved to their passions, they fall into the hands of the aspiring and unprincipled; and that corrupt government, which has an interest in deceiving the people, can desire nothing more favourable to their purposes, than a frenzied state of the public mind.

My friends, in this day of discord, let us cherish and breathe around us the benevolent spirit of Christianity. Let us reserve to ourselves this consolation, that we have added no fuel to the flames, no violence to the storms, which threaten to desolate our country. To Christian benevolence, let us add the higher duties of piety, a cheerful obedience and resignation to the will of our Creator. Thus living we shall not live in vain. In the most calamitous times, we shall bless those who are placed within our influence; we shall carry within us consciences void of offence; and we shall be able to look up to God, as our approving and protecting father, who, after appointing us the trials which we need, will grant us everlasting rest in heaven.

1 “Channing, William Ellery,” ed. Dumas Malone, Dictionary of American Biography (NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1930), 4:4-7.

2 James Madison, Humiliation and Prayer Proclamation, August 20, 1812.

3 William Ellery Channing, A Sermon Preached in Boston July 23, 1812, the Day of the Publick Fast (Boston: Greenough & Stebbins, 1812).

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!