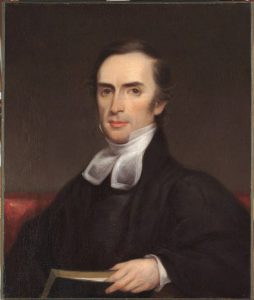

Francis William Pitt Greenwood (1797-1843) Biography:

Francis William Pitt Greenwood (1797-1843) Biography:

Born in Boston, he graduated from Harvard at the age of 17 and then studied theology at Cambridge. Upon his ordination, he became pastor of Boston’s famous New South Church in 1818, but became ill and resigned two years later. He spent a year in Europe and then returned to Baltimore, where he spent two years as editor of Unitarian Miscellany. In 1824, he relocated to Boston and became pastor of King’s Chapel, where he remained until his death. He faced recurring bouts of illness, and on one occasion on the advice of his doctor he went to Cuba to help his health. In addition to theology, he was also interested in botany and conchology (the scientific study and collection of mollusk shells) and became a supporter of the Boston Society of Natural History. He wrote for its journal and was also associate editor of the Christian Examiner. A number of his sermons were published as well as his hymnal for Christian worship. In 1839, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity from the Harvard College of Divinity.

PRAYER FOR THE SICK.

A

S E R M O N

PREACHED AT KING’S CHAPEL, BOSTON,

ON THURSDAY, AUGUST 9, 1832,

BEING

THE FAST DAY

APPOINTED BY

THE GOVERNOR OF MASSACHUSETTS,

ON ACCOUNT OF THE

APPEARANCE OF CHOLERA IN THE UNITED STATES.

BY F. W. P. GREENWOOD,

JUNIOR MINISTER OF KING’S CHAPEL.

PUBLISHED BY REQUEST.

B O S T O N:

LEONARD C. BOWLES

362 Washington Street.

1832.

S E R M O N.

JAMES V. 16.

CONFESS YOUR FAULTS ONE TO ANOTHER, AND PRAY ONE FOR ANOTHER, THAT YE MAY BE HEALED. THE EFFECTUAL FERVENT PRAYER OF A RIGHTEOUS MAN AVAILETH MUCH.

The apostle is urging the duty of intercession with God for the sick, and of mutual confession and forgiveness in the time of sickness. He thus joins moral duty with prayer, and signifies that an humble, repentant, charitable state of mind, is one condition on which the restoration of bodily health, and the answer of prayer depend. And who will object to the condition? Who will harden his heart against his neighbor, and refuse him his full forgiveness, when he sees the hand of the Lord lying heavily upon him, and hears the groans of his anguish, and thinks, whatever he may have been, or whatever he may have done, what a poor, feeble, suffering creature he is now? And who, on his own sick-bed, feeling the same hand on himself, and made sensible, by the near approach of another world, how vain and how wrong are the competitions and discords of this, and by he pressing thoughts of judgment and God’s holiness, of his own manifold imperfections, and repeated transgressions, can hesitate to acknowledge his errors, and forgive all who have sinned against him, as he himself hopes to be forgiven.

After thus recommending the holy dispositions which should accompany prayer for the wick, the apostle James asserts the efficacy of prayer in obtaining the implored blessing. ‘The effectual fervent prayer of a righteous man,’ he continues, ‘availeth much.’ He then mentions as an instance in proof, the case of Elias or Elijah, at whose earnest entreaty the Lord withheld rain from heaven, and afterwards caused it to be given again.

The translation, in our common Bible, of the latter clause of the test, is not a happy one. It is clearly tautology to say, at least according to the present meaning of words, that an effectual prayer will avail much. The single Greek word which is here rendered by the two English words ‘effectual fervent,’ is rendered by some commentators inwrought, or inspired; and these commentators consequently suppose that the whole passage applies only to the prayers of such persons as are inspired, or strongly and supernaturally moved to pray for particular blessings, which are granted at their request. And they say that the very instance given of Elijah, an inspired prophet, who prayed, as he was moved by divine impulse, for extraordinary and almost miraculous events, is a proof of the correctness of their interpretation. This rendering, though not to be overlooked, is not required, and in all probability is not the correct one. The original word (eveqyouuevn) is one from which our own word energetic is immediately derived. It means internally and strongly working. Wakefield translates the sentence thus; ‘The effect of the prayer of a righteous man is very powerful.’ And if the translators of the received version had omitted the word effectual, and rendered ‘The fervent prayer of a righteous man availeth much,’ they would have given us a more intelligible translation, and one, too, not far from the true meaning of the writer.

I have offered this brief criticism on the passage, because it is one which is constantly quoted, whenever the efficacy of prayer is the subject of discussion, and is not often clearly apprehended, on account of the dim and neutral character of the translation.

As to the doctrine of the text, the prevalence of the sincerely fervent prayer of a righteous man, I have no doubt of its soundness. Even if it could be conclusively shown that in this particular place, reference is had solely to the prayers of inspired saints in the first age of Christianity, and previously under the Jewish dispensation, yet there are so many general exhortations to prayer in the Scriptures, on the ground of its efficacy with One who hears and answers it, that I could not permit myself to deny that sincere, fervent, and righteous prayer is of much avail, not only with the petitioner, but with God. And this doctrine, which I believe to be a Scriptural, appears to me to be also a comforting and a rational doctrine. It is comforting to all who love God, to perceive him brought so near to them; to be confident, from the assurances of his own word, that he hears all they say to him; that he not only hears, but attentively and graciously listens, with the purpose of granting those requests which can be granted, consistently with his own wisdom, the real good of the petitioner, and the happiness of the great whole. Why should prayer be made, if God does not hear? Why should God hear if not to listen: and why should he listen, if not with a purpose connected with the prayer? We are not justified in expecting any miraculous answer to prayer, but a direct answer to prayer, through ordinary means, we are justified in expecting, if the gift is expedient for us; and if it is not granted we should rest satisfied that it is not expedient.

“If what I ask my God denies,

It is because he’s good and wise.’

Beyond a very few steps, and a very short distance in the path of God’s operations, our eyes are too weak to see. It is highly unbecoming in us o say, or to presume, that there is nothing, because we see nothing beyond, or that we know exactly how those events which we do see re brought about by a ruing Deity. There is a regularity and order in that which we discern, which we call natural, and which none but a fanatic would look to see interrupted. But without this regularity and order being interrupted, blessings may come to us, or evils may be averted from us, through the steps of this very order, this natural regularity and order, at the voice of our prayer, and a bidding from on high. There is nothing irrational in this, for there is nothing irrational in believing that we are ignorant, and that God, who orders all things, may grant us special blessings by common means; and that he will grant them, because, in a revelation which we agree is from him, he has promised so to do.

To occupy no longer time in introduction—though I easily might on so wide, so fruitful and so interesting a subject—and to come at once to the occasion of our present assembling together, let me ask who knows anything of the origin and mode of progress of the disease which we have prayed God to avert from us? Who knows what place or what person it will next attack? Who knows how it journeys from place to place, and from person to person? Who knows how near it may be to ourselves, or whether it will enter our gates at all? Who knows how many it will visit if it should come, or how many of those whom it visits it will spare, and how many it will not spare from the consummation of death? Who knows how soon it will leave a town or city, after it has once entered? Who knows at what time it will leave the world, or whether it will ever leave the world? Who knows whether sin may not be the cause of this disorder, and whether prayer, righteous prayer, may not be among the most effectual means of averting it? At any rate, the servant of God who has prayed in sincerity that the calamity may not fall on himself, his household and his neighbors, has performed his duty in seeking the throne of Grace. He knows that he has been heard kindly by Him who sitteth on the throne, and that whether he is to be spared or not, whether his household and neighbors are to be spared or not, the event will be wisely and mercifully ordered. He feels, moreover, that his own affections have been raised and his own charities been warmed and extended by his devotion; and that he is consequently better prepared for sickness and for health, to be taken or to be left.

This last is a highly important consideration, and is ground on which all sober and pious persons can stand together, whatever may be their differences of opinion with regard to the direct efficacy of prayer on the mind of the Deity, or rather the literal correspondence of its efficacy with the promises of scripture. All such will agree that the effect of prayer on the devout heart is great and beneficial; that it softens and sanctifies; that it places the petitioner, by the influence thus exerted on his dispositions and life, in the best position for receiving and enjoying the blessings, and bearing and improving the chastisements of Heaven. All will agree, too, that if prayer has not this effect on the hearts and lives of those who pray, it can have no effect on Him who hears; and that whatever may be the precise way in which the fervent prayer of a righteous man availeth, one thing is undeniable, if a prayer be not one of sincerity and righteousness it will avail nothing.

What, then, should be some of the moral influences and effects of prayer on the present occasion? What must be some of the moral influences and effects of fervent and righteous prayer?

In order to answer these questions let us consider, first, what it is which we pray God to avert from us. Some call it the blighting curse of God. I will not call it so. Some call it a fierce demon let loose upon poor mortals, and some a horrid monster glutting itself with prey. I give my assent to no such epithets. It is a wasting disorder, melancholy in its character, but commissioned with the intentions of God’s omniscience. It is a judgment on the earth. It is a warning to the people against sin and uncleanness. It is a trying but also a just providence. These are the names by which I prefer to describe it; and in painting it to the imagination, I would draw it not with eyes angry and bloodshot, and a mouth breathing out fumes from the bottomless pit, but as an angel, a mourning as well as a retributive angel, bearing the sword of the Almighty not in vain, but hiding its sad countenance with one hand, while with the other it deals the speedy blow.

1. I have called it a judgment on the earth, and a warning against sin and uncleanness. And is it not reasonable and justifiable to call it so, when we are told that it seizes first and principally on the intemperate and the unclean? How can the voice of God speak more plainly against these forms of unrighteousness, than in this mandate to his destroying angel? In praying that the disorder may not be sent among us, we should call to mind this purpose of its mission, and remember the vices against which it appears so evidently to be sent, and thus strengthen our conviction of their fatal nature and exceeding sinfulness, and redouble our efforts to root them out. How can we expect that the disease will keep away, when that which invites the disease is permitted to remain? It is a solemn truth that every intemperate and corrupt person, that every keeper and every supporter of the haunts of profligacy and riot is laboring to bring the so much dreaded pestilence to the place in which he dwells. Should the punishment come, it will be called a demon and curse—when behold the demon and the curse are even now among us and upon us. Do we expect to sin on and sin on forever, without any notice taken, and without a retribution? While we pray, we would meditate on these things, with the purpose of acting accordingly, and then we may hope that our prayer will be availing.

2. But the disease does not entirely confine itself to the above described victims. Though it principally selects these, yet it falls occasionally on the sober and pious and on innocent children. And ought we not to be taught by this, not to boast of our virtue, nor to be sure of exemption, not to elevate ourselves in fancied security above the poor creatures whose vices are their exposure? Humility will always accompany sincere prayer. We are all exposed in some degree; and therefore it should be a primary consideration with us how we shall be prepared; and surely no better preparation will present itself to the Christian than that of mercy and charity. While we are roused to act against sin, it will be in a temper of great pity for the sinner, and with especial care that we do not fall into sin, particularly the sin of the Pharisee, ourselves. ‘Vengeance is mine; I will repay, saith the Lord.’ Let us be careful that we interfere not with the Supreme prerogative. It is the Lord’s to send abroad his terrible and righteous judgments; it is ours to be kind and charitable, humble and watchful.

3. We are to be prepared, but not afraid. ‘The Lord is the strength of my life,’ exclaims the Psalmist, ‘of whom shall I be afraid?’ It is the tendency of true prayer to lift up the heart above fear, because it lifts it up into the presence of God. Can we run to an Almighty Guardian, and acknowledge his power to save, and then feel and talk and act as if we had no guardian? Shall we come into the temple of the Most High, and address him as our ever present God and watchful Father, and after we have gone from the door, tremble at the first rumor of disease, as if we had no God and no Father? I say that he who prays sincerely, not only prays to be delivered from pestilence, but prays to a being who sends, limits and rules the pestilence, who is the Lord of life and death, who is the Judge of all the earth, who will do what is right, and who is the refuge and defense of all those who trust in him. Such a suppliant cannot be overcome by unworthy dread. He has gone and placed his life in the hands of its Author, and his blessings and comforts in the hands of their Giver. They are locked up—he is sure of them—and therefore he is not afraid. My friends, if we come here and pray, and if other congregations of our brethren assemble to pray, merely because we are afraid; and if the effect of our praying will be only to make us more afraid, we have not prayed aright—we could not have been doing a more ineffectual thing—our prayers have been vainer than vanity. He who has been fervently and righteously praying that this pestilence may be averted from him and his, will rise up from his knees, a fearless man. He will feel himself piously and rationally superior to the exaggerated alarms which have operated on some. Rather than permit a sufferer from the disease to be shamefully deserted and neglected, he will go and minister to him himself. Rather than permit the lifeless frame of a fellow creature to lie on the bare earth, he will dig a grave with his own hands, and then fall again on his knees, and commit that body to the earth, and the spirit to God who gave it. And when he has done this, he will feel that his prayer has availed much.

4. But while fervent and righteous prayer will make us fearless, it will have no tendency to make us neglect other proper means of prevention or of cure. It will, on the contrary, lead us to view those means with increased respect and gratitude, as the merciful provision of God, and use them diligently and advisedly, as by his ordination and appointment. Whence are all these means? What are all exciting, soothing and healing medicines; what are all purifying and disinfecting agents; what are all sanative applications, but treasures drawn from his storehouse? So far from despising them, therefore, the religious man will regard them as things divine; he will regard medical skill, as an art and gift divine; and he will make use of them when necessary, as by divine commandment. The health which God bestows, he will endeavor to preserve or restore by means which the finger of God points out, not relying on his own strength or merits and leaving the event to Him. He loves to pray to his gracious Father, but he will not tempt him. He is no fatalist. He believes it to be disobedience to God, not to employ the aids which God furnishes for his use; he therefore employs, but does not finally trust in them. He trusts in nothing but the divine wisdom, mercy and promises, and in these he trusts to the end.

Let us then confess our faults one to another, and let us pray one for another. Let us confess our faults to God, and pray for ourselves. If our prayers are fervent and righteous; if they awaken us to the evil and danger of sin; if they make us humble and unassuming; if they inspire us with a cheerful courage, united with a rational prudence, we may be confident that they will avail much. They have availed much. They have prepared us in the best possible manner against the hovering pestilence; they have saved us from sin, which is more dreadful than pestilence. God has heard them; and he will answer them, if not by temporal immunity, yet y the answer of eternal salvation.

END.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!