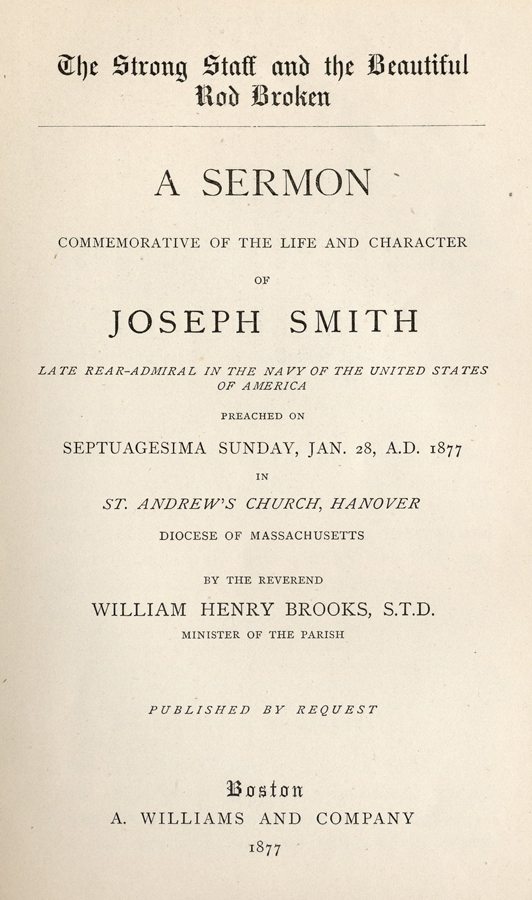

This sermon was preached by William Henry Brooks in Boston in 1877.

ROD BROKEN

A SERMON

COMMEMORATIVE OF THE LIFE AND CHARACTER

OF

JOSEPH SMITH

LATE REAR-ADMIRAL IN THE NAVY OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

PREACHED ON

SEPTUAGESIMA SUNDAY, JAN. 28, A.D. 1877

IN

ST. ANDREW’S CHURCH, HANOVER

DIOCESE OF MASSACHUSETTS

BY THE REVEREND

WILLIAM HENRY BROOKS, S.T.D.

MINISTER OF THE PARISH

JEREMIAH XLVIII. 17.

“All ye that are about him, bemoan him; and all ye that know his name, say, How is the strong staff broken, and the beautiful rod!”

“A power has passed from the earth.”

A “strong staff” of greatness and a “beautiful rod” of goodness, joined together more closely and more inseparably than if “with hoops of steel,” has been broken.

All that were “about him,” whether as kindred, friends, companions in arms, or compatriots, “bemoan” his departure hence. “All that knew his name,” as that of one of the ablest, bravest, and purest defenders of their country, can truly say that “a prince and a great man is fallen.”

“Greatness and goodness are not means, but ends!

Hath he not always treasures, always friends,

The good great man? Three treasures,—love and light,

And calm thoughts, regular as infant’s breath;

And three firm friends, more sure than day and night,—

Himself, his Maker, and the angel Death.”

On the 17th of January, in the year of our Lord 1877, “very early in the morning,” “when it was yet dark,” at the capital of our nation,—just one day after the completion of sixty-eight years he had been in the service of his country,—it pleased Almighty God, in His wise providence, to take out of this world the soul of Joseph Smith, Rear-Admiral in the Navy of the United States, the oldest officer in that branch of the public defence.

Had he lived in this world until the 30th of the coming March, he would have attained the goodly age of eighty-seven years.

“The mere worldling,” obedient to the powers of the Devil, “is torn from the world which is the only sphere of delight which he knows, as the fabled mandrake was torn from the earth shrieking and with bleeding roots.

“He is like the ship which by some fierce wind is dragged from its moorings, and driven furiously to perish on the rocks;” but this servant of God, obedient to the powers of the world to come, was “as a ship, which has been long waiting in harbor, and joyfully, when the signal is given, lifts its anchor, and makes sail for the harbor of eternity.”

When his spirit returned unto God who gave it, there was no long and bitter struggle, so painful to witness; but,—

“Like a shadow thrown

Softly and lightly from a passing cloud,

Death fell upon him;”

And, in the valley of that death-shade,—

“There calm at length he breath’d his soul away.”

The quiet and composure of his departure from earth to Paradise—unbroken even by a solitary sigh—reminds us how “the Jewish doctors taught that the angel Gabriel drew gently out with a kiss, the souls of the righteous from their mouths; to something of which kind, the phrase so often used to express the peaceful departure of the saints, In osculo Domini obdormivit, must allude.”

The secretary of the Navy (the Hon. George M. Robeson) in a Special Order, remarkable for its simplicity, directness, and beauty, with deep regret announced the death of Rear-Admiral Smith, as that of the oldest officer in the naval service; spoke of this gallant officer as having risen rapidly in his profession, and honorably distinguished himself in every grade; and, after expressing the opinion that his death would be universally lamented by the service and the country, ordered that the customary honors belonging to his rank be paid to his memory at all the navy-yards and naval stations of the United States, and on the flag-ships of the several squadrons of the navy of the same.

On January the 20th, the Friday following his death, his body was borne on the shoulders of eight seamen—eight distinguished officers of the army and navy acting as pall-bearers—into St. John’s Church, Washington,—in the presence of a large congregation, very many of which were officers of the navy,—where he had so long worshipped, and of which he had so long been a useful member.

Here the first part of the Burial Office—the sentences, the psalms, and the lesson—was said.

The second part of the Burial Office—the meditations, the solemn interment, and the prayers—was said in the chapel at Oak Hill Cemetery, Georgetown, D.C., after which his precious dust was placed in the family vault in the family vault in that “Acre of our God.”

At his own request, all the services and all the honors on this occasion were of the simplest character, compatible with Christian and naval propriety.

Joseph Smith—the son of the Hon. Albert Smith and Anne Lenthall Eells, his wife—was the second of nine children, and was born in Hanover, Mass., on the 30th of March, A.D. 1790.

At the time when he, an innocent, happy little boy, was playing in the green fields of Hanover, the country, of which he was to be a brilliant ornament and gallant defender, did not possess even a single ship of war. But such was the rapidity of change in this particular, that, ere threescore years and ten had winged their flight, he saw his beloved country in the number and power of her ships of war almost, and in the skill and efficiency with which they were served quite, the peer of any nation of the world.

From the merchant-service, he entered the Navy of the United States, as Midshipman, on the 16th of January, 1809.

He was appointed Lieutenant on the 24th of July, 1813. Having entered the service but three years before the last war between our own and the mother country, he was soon called upon to give evidence of his willingness and ability to “be a safeguard unto the United States of America, and a security for such as pass on the seas upon their lawful occasions.”

In the time of testing, he was not found wanting. In will and in deed, he was fully abreast with the occasion.

Being one of the officers in the gallant squadron on Lake Champlain, under the charge of the able and dauntless Commodore Thomas McDonough; serving as First Lieutenant of “The Eagle,” commanded by Capt. Henley,—of whose competency and bravery he ever cherished a very high opinion,—in the hard-fought battle of Plattsburg Bay, which occurred on the 11th of September, 1814, he was entrusted with responsible duties, which for one so young—he being then in this twenty-fifth year only—were discharged with wonderful zeal, fidelity, and skill. In the efforts resulting in the happy victory gained by our countrymen in that fierce and bloody contest with superior number, we are quite safe in ascribing to him, under the guidance and blessing of the Almighty, “who is the only Giver of victory,” and instrumentality of the very first importance.

During the battle “The Eagle” was exposed to a destructive and almost constant storm of iron hail; and, as “the booming shots” in rapid succession reached their intended destination, it was readily seen with almost “brave despair” that the furious cannonade would soon disable the ship.

The time came when the entire armament of one side of the vessel, through the well-served guns of its foes, was rendered useless; and it seemed as if “The Eagle” of the water, which, like the eagle of the sky after which it was named, had been—

“Proudly careering her course of joy:

Firm, on her own mountain vigor relying,

Breasting the dark storm, the red bolt defying,”—

was now, wounded, lacerated, the life-blood ebbing away, about to fall a prey into the hands of her enemies.

In this exigency Lieut. Smith obtained permission from his superior officer to send out a small boat, with an anchor, which, when cast into the water sufficiently distant from the ship, enabled it, through the cable attached to the anchor, so to be shifted as to bring the uninjured armament on its other side to bear, with its missiles of defence and destruction, on the wooden walls of its surprised assailants.

Having delivered its fire, he would have the vessel shifted, so as to present to the enemy its useless side,—thus securing comparative protection while preparing for another broadside,—and, when the guns were ready for action, would have the vessel hauled into position, when it would again pour upon the enemy its storm of shot and shell.

While this simple expedient of changing the side of the vessel next to the foe—consuming, perhaps, not more than fifteen minutes each time—prevented the vessel from becoming a prey to captors, it also had no small influence in contributing to the general victory obtained by the brave defenders of our country in that famous naval contest.

In appreciation of his gallantry on this occasion, the Congress of the United States bestowed upon him a medal.

During this battle, by the compression of the air resulting from the passage of one of the balls from the enemy’s cannon very near to him, his coat was very much torn, and himself was thrown senseless upon the deck.

He was taken up for dead; but, by the blessing of God upon the use of proper remedies, he was soon restored to consciousness, “and felt no harm.”

An incident in connection with the manning of “The Eagle” will serve to show his quickness and fertility of resource in availing himself of aid, when, perhaps, to almost any other person, none would have seemed attainable.

Six weeks before the launching of “The Eagle,” the timber of which it was constructed was quietly growing in its native home in the adjacent forests.

When launched, it was found that to be properly and efficiently manned, one hundred men would be required, while there were but about thirty available for this work. Receiving from Commodore McDonough a requisition on Gen. Macomb, who was in command of the land forces at Plattsburg, for a detail of soldiers for completing the crew of “The Eagle,” he presented it in person, and was told in reply by the General that he was expecting the enemy in superior numbers—fourteen thousand—under Gen. Prevost, the Governor-General of Canada, to come at any time, and that as his own force—about two thousand—was so much inferior numerically, he could not furnish him with the sorely needed men. The Lieutenant, after thinking a few moments, asked the General if he had not some men under discipline for military offences.

He replied that he had, and that he would gladly part with them.

The Lieutenant, having received the proper warrant, proceeded to a spot where the men, under a guard, were at work in a red clay soil, throwing up breastworks.

With but very scanty clothing, matted hair, and smeared with the unsightly clay, these poor fellows presented a pitiable sight.

They were well content to exchange the scene of their labor and punishment for a place on “The Eagle,” whither they were speedily carried in small boats.

Arrived on board, the Lieutenant saw that they were provided with the means for bathing, procured for them all the clothing that could be obtained, had the cook prepare for them a supper of the best the vessel afforded, and furnished them with blankets, that they might enjoy a comfortable and refreshing sleep.

This was ingenious—more than that, this was humane—most of all, this was Christian.

These very men, who were not only no help to Gen. Macomb, but, on the contrary, were a source of weakness, as the guard necessary for their oversight and detention detracted from the total sum of his efficient soldiers, were converted into useful helpers, and did good, loyal service in the day of battle.

It pleased God so to order it, that he should be the last of those naval officers who, in the second war with Great Britain, distinguished themselves.

Would it be unjust to them, and untrue of him, if it should be said,—

“This was the noblest Roman of them all.

* * *

His life was gentle, and the elements

So mix’d in him, that Nature might stand up,

And say to all the world, This was a man.”

In the following year, 1815, he was in the Mediterranean squadron, under the gallant Commodore Decatur; and in the war with the Dey of Algiers,—occasioned by his plundering, capturing, and condemning American vessels, and selling their crews into slavery,—at the capture on the 18th of June, OF THE Algerine vessels (a frigate of forty-four guns, and a brig), he rendered great assistance, and behaved with extraordinary courage, favorable mention of which was appreciatively made in the official report.

On the 3d of March, 1827, he was commissioned as Commander; being at that time attached to the Navy Yard in Charlestown, Mass.

In 1834 he became Commandant of that extensive and very important yard.

On the 9th of February, 1837, he was commissioned as Captain.

In 1840 he was Commander of the Receiving-Ship “Ohio,” at least one of the noblest ships, if not the noblest ship of the line, over which a flag ever floated.

In 1845 he had the command of the Mediterranean Squadron.

Amiable, considerate, exemplary in word and deed, it is not surprising that he should have had great influence with the crew of his ship.

A single instance will abundantly illustrate this point. Many years ago, when the crew were entitled by law to a daily ration of grog,—a mixture of spirit and water, not sweetened,—they were allowed, if so disposed, to commute it for a sum of money equal to its value.

Through his influence, every one of the crew, with a single exception, commuted.

This solitary sailor declined to commute, and insisted on the enjoyment of his legal right in this regard.

Accordingly, each morning, at the proper time, the grog-tub was brought forth, the usual call of summons was made, and the officer having this duty in charge dealt out to the solitary recipient his legal quantity of stimulant.

Finding that this insister on his regulation rights was determined to persevere in the course he had entered upon, he was subsequently transferred to another ship; thus rendering the entire crew, in this particular, one in sentiment and one in action.

On the 25th of May, 1846, he was appointed Chief of the Bureau of Yards and Docks, the duties of which office he discharged with great ability and faithfulness until the spring of 1869, when bodily infirmity constrained him to resign.

On the 16th of July, 1862, he was commissioned as Rear-Admiral.

He went on the Retired List, but rendered valuable service to the country in the performance of special duty at the Navy Department, in Washington.

In 1871 he withdrew entirely from active service, and

“In sober state,

Through the sequester’d vale of “private” life,

The venerable patriarch guileless held

The tenor of his way.”

In these days, when instances of corruption, bribery, and theft, on the part of those holding positions of trust, are far from being rare exceptions to a general rule; when good citizens, grieved and discouraged at the manifestations of “conceiving and uttering from he heart words of falsehood,” are tempted to say, “Judgment is turned away backward, and justice standeth afar off: for truth is fallen in the street, and equity cannot enter. Yea, truth faileth,” it is not only refreshing but salutary to look upon the example of a man who, placed in a position where he had the opportunity, if so disposed, to amass vast wealth by the prostitution of his office to his own personal advantage, and who, if he had availed himself of the opportunity, could have concealed his conduct from the knowledge of all save a few interested ones, and the all-seeing eye of the Almighty, so conducted himself in office with—

“That chastity of honor which felt a stain like a wound,”—

that no one, who understood his character, would have dared to suggest, either for or without reward, the deviation on his part of a hair’s-breadth from the line of strict integrity.

If the prophet, in the capital of our country, had proclaimed the opening words of the First Lesson of this morning, “Run ye to and fro through the streets, . . . and see now and know, and seek in the broad places thereof, if ye can find a man, if there be any that executeth judgment, that seeketh the truth,” this incorrupt and incorruptible servant of his country could have said—if his shrinking modesty could have been sufficiently overcome to allow him to speak words affirming the integrity of his public life, both in purpose and execution—what Samuel said to all Israel: “Whose ox have I taken? Or whose ass have I taken? Or whom have I defrauded? Whom have I oppressed? Or of whose hand have I received any bribe to blind mine eyes therewith? And I will restore it you.”

And, in such an event, what would his fellow-countrymen have replied, but in the words of all Israel in answer to the testifying by Samuel to his own integrity?—“Thou hast not defrauded us, nor oppressed us; neither hast thou taken ought of any man’s hand.”

Whatever of worldly substance he accumulated, was the result of honest industry. To that substance may be truly applied the words spoken by John Randolph, concerning a temporal estate gathered by a man of rigid integrity: “Sir, there is not a dirty shilling in it.”

When such an one, whose example in public life has been “without spot, and blameless,” passes from the life that now is, how can we refrain from the prayer of the heart, if we do from that of the lips?—“Help, Lord; for the godly man ceaseth; for the faithful fail from among the children of men.”

He was a “man that had seen affliction,” grievous to be borne, time and time again repeated.

He recognized it as God’s visitation, perhaps to try his patience for the example of others, or perhaps that this faith might be found, in the day of the Lord, laudable, glorious, and honorable, to the increase of glory and endless felicity; and so, when “woe succeeded a woe as wave a wave,” he, through the help of the Holy Ghost, never cast away his confidence in the Father of mercies, nor placed it anywhere but in Him, making the sentiment of the words, and the words themselves, of the patriarch Job, his own: “Though He slay me, yet will I trust in Him.”

His wife, “the desire of his eyes,”—previously Harriet Bryant, of Maine,—a faithful, devoted, and Christian companion, “an help meet for him,” was taken from him by “a stroke” of a peculiarly painful character; dying from the effects of a fearful railroad accident, a very few days after its occurrence.

A son,—Joseph Barker,—“a creature of heroic blood,” while in command of the fine frigate “Congress,” of eighteen hundred and sixty-seven tons burden, during her engagement, on Saturday, the 9th of March, 1862, in the James River, with the mailed monster “Merrimac,” was killed by a shell from the enemy.

“The ‘Merrimac,’ choosing her position distant from the frigate about a hundred yards only, discharged broadside after broadside of her hundred pound shot and shell, raking the frigate from stem to stern.

“The carnage was awful.

“The decks were in an instant covered with dismounted guns, and mangled limbs, and gory blood.

“She was set on fire in three separate places.

“The fresh breeze fanned the flames, which timbers and planks, dry as tinder, fed. The fiery billows burst forth as from a volcano.

“The wounded could not escape, and were exposed to the horrible doom of being slowly burned alive.

“This sight could not be endured by the surviving officers and crew.

“With tears and anguish, the flag was drawn down.”

When the depressing tidings, that “The Congress” had struck her flag, came to the ears of the father of her intrepid commander, without knowing “that the chieftain lay unconscious of his” noble parent, he said, “Then Joe is dead.”

These words—the expression of well-founded faith in the inflexible purpose of his son, never to yield victory to the foe—we “should not willingly let die.”

Another son,—Albert Nathaniel,—who commanded a vessel in the squadron under Commodore Farragut, at the capture of New Orleans, on the 25th of April, 1862, acquitted himself on that occasion with that wisdom and bravery which were his, both in his own right, and by virtue of descent from his illustrious sire.

This son, well accomplished in the science and practice of naval warfare, subsequently became Chief of the Bureau of Equipment and Recruiting.

He died of disease contracted in the service of his country; to which he had ever been loyal and true.

In these afflicting dispensations from the Father’s hand, that religion in which he implicitly believed supplied him with all needed support and consolation, since—

“’Tis hers to pluck the amaranthine flower

Of Faith, and round the Sufferer’s temples bind

Wreaths that endure affliction’s heaviest shower,

And do not shrink from sorrow’s keenest wind.”

He did not submit to the will of God.

To do this is not Christian; for it is to yield to another because on the side of that other there is power, and to do otherwise would be worse than useless.

It is enforced resignation, and consequently is but little worth, because it is not the making of God’s will the will of His creature. He did more and better than this:—he acquiesced in God’s will; by the help of Divine grace, substituting that holy, wise, and unerring will for that which by nature was his.

Thus, through Divine power, did he “glory in tribulations: knowing that tribulation worketh patience, and patience, experience, and experience, hope, and hope maketh not ashamed,” “which hope he had as an anchor of the soul, unfailing and steadfast, and reaching, as it were, by a cable laid out of the Ship,—the vessel of the Church,—and not descending downward to an earthly bottom beneath the troubled waters of this world, but, what no earthly anchor can do, extending upward above the pure abysses of the liquid se of bright ether, and stretching by a heavenward cable even into the calm depths and solid moorings of the waveless harbor of Heaven; whither our Forerunner Jesus has entered, and to Whom the Church clings with the tenacious grasp of Faith: as a vessel is moored by a cable or an anchor firmly grounded in the steadfast soil at the bottom of the sea.”

All alone, he received the manifold gifts of grace in Confirmation, or laying-on of hands, from Bishop Eastburn; and, by the reception of that Apostolic rite, ratified and confirmed the solemn obligations entered into on his behalf, in his tender age, at the time when in Holy Baptism he was grafted into the body of Christ’s Church.

At his confirmation, he wore the full uniform of his high rank,—the highest attainable in the navy in those days; not that he might thereby deepen the impression of his eminent position on those then present,—for vanity and ostentation, in all their forms, were foreign to his nature,—but that he might declare that, in this repeating of his oath of fidelity to “the Sovereign Commander of all the world,” it was not merely as a private disciple, but also as an officer in that branch of the nation’s service which “hath ever been its greatest defence and ornament;. . . its ancient and natural strength,—the floating bulwark of our” country.

It is not often that the eye rests upon a sight so touching and suggestive as that which, in the closing years of his life, was presented by his attendance upon and the reception of the Holy Communion in St. John’s Church, Washington, at an hour so early in the morning of the Lord’s Day, that very many of the inhabitants of the capital of our country had not even awaked.

To behold his reverent deportment, to look upon his sweet and peaceful face, to witness his infirm steps as he slowly approached the chancel-rail, to see him in meek devotion “fall low on his knees before the footstool” of the Great King,—knees stiffened with age, the bending of which must have caused him pain,—while partaking of the blessed Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ,—was a sight which, on those who were privileged to see it, would be indelibly impressed.

At the time of his death, he was, as he had been for twenty-one years, the senior Church-Warden of St. John’s Church, Washington. Such was the esteem in which he was held by his fellow-parishioners, that when, owing to his physical inability, he could no longer discharge the duties of that high and important office, and he desired to give place to another, they declined to accede to his desire, and continued him in office; and, in thus honoring him, highly honored themselves.

That branch of the Church Catholic in which, by the reception of the Seal of the Lord in Confirmation, he was strengthened with the Holy Ghost the Comforter, and assumed the vows of Christian discipleship, found in this upright and God-fearing man one intelligently and firmly attached to its principles, which are those of Christianity “as understood by the Primitive Church, grounded upon Holy Scripture, as interpreted by universal primitive consent and practice,” and one abundantly satisfied with its provisions for the nourishing and developing of the life of God in the soul of man.

Under the tutelage of the gentle and bountiful Church,—“the Mother of us all,” descended from the Apostles of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, through the Church of England,—fed with “the sincere milk of the word,” he grew in grace; nourished with that ‘strong meat” which “belongeth to them that are full age,” he developed into a full-grown man in Christ Jesus; and through her Sacraments, sacramental ordinances, and other means of grace, in

“An old age serene and bright,

And lovely as a Lapland night,”

matured for glory.

Tenderly and lovingly did she hold him in her patient and unwearied arms, until she humbly commended his soul into the hands of the Almighty, the faithful Creator, and most merciful Saviour, most humbly beseeching Him that it might be precious in His sight, having been washed in the blood of that immaculate Lamb, that was slain to take away the sins of the world.

Never did she cease her labor, her care and diligence, to bring him unto that agreement in the faith and knowledge of God, and to that ripeness and perfectness of age in Christ, that there might be no place left either for error in religion, or for viciousness in life, until he was received, out of her strong and comforting arms, into those heavenly habitations where the souls of those who sleep in the Lord Jesus enjoy perpetual joy and felicity.

We have thus endeavored to show that, in the character of this distinguished citizen of our country, the two elements that so largely and strongly influence the world in which we live—greatness and goodness—were powerfully and beautifully combined.

In the words of the First Lesson of this evening, “Weep ye not for the dead, neither bemoan him: but weep sore,” that our beloved country can no longer lean upon the “staff” of his lofty, symmetrical, and robust greatness, and can no longer carry with her, in the various walks of the public service, the “rod” of his earnest, unvarying, and whole-hearted goodness.

Well may we feel that while, by the taking-out of the world of the soul of our deceased brother, Paradise is the richer, the present world is the poorer.

We sorrow, but not as others without hope, for him who now sleeps in Jesus.

While we mourn for our loss of him, as a true-hearted friend, a patriotic citizen, a faithful servant of the Republic, we should especially and chiefly mourn for our loss of him as a Christian, for the all-sufficient reason that

“A Christian is the highest style of man.”

May God the Holy Ghost, the Sanctifier of the faithful, daily increase His manifold gifts of grace in this congregation who knew and loved him, and who, in this consecrated house of prayer, have with him worshipped the Triune God, that they like him, having been received into the ark of Christ’s Church, and being steadfast in faith, joyful through hope, and rooted in charity, may so pass the waves of this troublesome world, that, finally, they may come in safety to the haven where he now is, and where they would be,—the land of everlasting life!

“He maketh the storm a calm, so that the waves thereof are still.

“Then are they glad because they be quiet: so He bringeth them unto their desired haven.”

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!