Lyman Beecher (1775-1863) graduated from Yale in 1797, having studied theology with Timothy Dwight (the president of Yale). He was ordained in 1798. He preached at: the Presbyterian Church in East Hampton (1799-1810), the Congregational Church in Litchfield, CN (1810-1826), the Hanover Street Church in Boston (1826-1832), and the Second Presbyterian Church in Cincinnati (1832-1842). Beecher also served as president of Lane Seminary in Cincinnati (1832-1852).

This sermon was preached by Lyman Beecher in 1817 in Boston on the Bible as a law book.

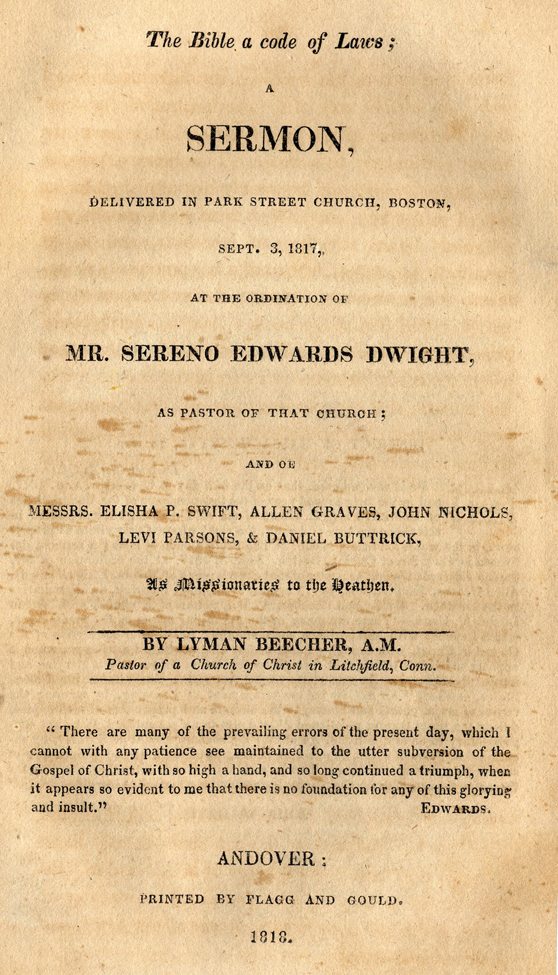

A

SERMON,

DELIVERED IN PARK STREET CHURCH, BOSTON,

SEPT. 3, 1817,

AT THE ORDINATION OF

MR. SERENO EDWARDS DWIGHT,

AS PASTOR OF THAT CHURCH;

AND OF

MESSRS. ELISHA P. SWIFT, ALLEN GRAVES, JOHN NICHOLS, LEVI PRSONS, & DANIEL BUTTRICK,

As Missionaries to the Heathen.

BY LYMAN BEECHER, A.M.

Pastor of a Church of Christ in Litchfield, Conn.

“There are many of the prevailing errors of the present day, which I cannot with any patience see maintained to the utter subversion of the Gospel of Christ, with so high a hand, and so long continued a triumph, when it appears so evident to me that there is no foundation for any of this glorying and insult.” Edwards.

PSALM XIX. 7, 8, 9, 10.—“THE LAW OF THE LORD IS PERFECT, CONVERTING THE SOUL: THE TESTIMONY OF THE LORD IS SURE, MAKING WISE THE SIMPLE: THE STATUTES OF THE LORD ARE RIGHT, REJOICING THE HEART: THE COMMANDMENT OF THE LORD IS PURE, ENLIGHTENING THE EYES: THE FEAR OF THE LORD IS CLEAN, ENDURING FOREVER: THE JUDGMENTS OF THE LORD ARE TRUE, AND RIGHTEOUS, ALTOGETHER. MORE TO BE DESIRED ARE THEY THAN GOLD, YEA, THAN MUCH FINE GOLD; SWEETER, ALSO, THAN HONEY, AND THE HONEY-COMB.”

We have, in this Psalm, a concise account of the discovery made of the glory of God, by his works and by his word. “The heavens declare his glory, and the firmament sheweth his handy work.” But these disclosures of the heavens, “whose line is gone out through all the earth, and their words to the ends of the world,” though they illustrate the glory of Jehovah, and create obligation, and discover guilt; are not sufficient to restrain the depravity of man, nor to disclose an atonement for him, nor to announce terms of pardon, nor to sanctify the soul.

But the Law of the Lord is perfect. Adapted to the exigencies of the lost world, it speaks on all those subjects, on which no speech is heard from the heavens, and is attended with glorious efficacy. It converts the soul; it makes wise the simple; it rejoices the heart; it produces a fear of the Lord, which endures forever; and to all who have felt its sanctifying power, it is more precious than gold, and sweeter than honey.

The text, then, teaches us to regard the word of God as containing the laws of a moral government revealed for the illustration of his glory in the salvation of man.

In discoursing upon this subject, it is proposed

I. To illustrate the nature of moral government; and,

II. To show that the Scriptures are to be regarded as containing a system of moral Laws, revealed to illustrate the glory of God, in the salvation of man.

A moral government is the influence of law upon accountable creatures. It includes a law-giver: accountable subjects: and laws intelligibly revealed, and administered with reference to reward and punishment. To accountability in the subjects are requisite, understanding to perceive the rule of action; conscience to feel moral obligation; and the faculty of choice in the view of motives. Understanding to perceive the rule of action does not constitute accountable agency. Choice without the capacity of feeling obligation, does not constitute accountable agency.—But the faculty of understanding, and conscience, and choice, united, do constitute an accountable agent. The laws of God and man recognize these properties of mind, as the foundation of accountability.—A statue is not accountable; for it has no faculty of perception or choice: an idiot is not; for, thou he may have the faculty of choice, he has no competent understanding to perceive a moral rule, nor conscience to feel moral obligation; and a lunatic is not; because, though he may have choice and conscience he has not the unperverted exercise of his understanding.

The faculties, then, of understanding, conscience, and choice, constitute an accountable agent. Their existence is as decisive evidence of free agency, as the five senses are of the existence of the body; and nothing is inconsistent with free agency, or annihilates the evidence of its existence, which does not destroy one or more of these faculties of mind.

Law, as the medium of moral government, includes precepts and sanctions intelligibly revealed. The precept is directory; it discloses what is to be done.—The sanctions are influential; they present the motives to obedience included in the comprehensive terms of reward, and punishment. But, to have influence, the precepts and the motives must be presented to the mind. The law in all its parts must be intelligible; otherwise it is not a law. A law may be unknown, and yet be obligatory, when the ignorance is voluntary; but never, when it is unavoidable. The influence of law, as the medium of moral government, is the influence of motives upon accountable creatures; and the effect of this influence is always the actual exercise of free-agency in choice or action. The influence of motives cannot destroy free-agency; for it is always the influence only of persuasion, and results only in choice, which in the presence of understanding and conscience, is free-agency. If there were no objects of preference or aversion exhibited to the mind; there could no more be choice or free-agency, than there could be vision without external objects of sight. Direct irresistible impulse, moving the mind to action, would not be moral government; and if motives, in the view of which the mind chooses and acts, were incompatible with free agency, accountability and moral government would be impossible.

The administration of a moral government includes whatever may be necessary to give efficacy to its laws. Its chief influence is felt in the cognizance it takes of the conduct of subjects, and the evidence it affords of certain retribution according to their deeds. I some points, there is a coincidence between natural and moral government; and in others, a difference. They agree in this fact, that the subjects of each are influenced to act, as they would not without government. To suppose complete exemption from any kind or degree of influence from without, to be indispensable to free-agency, is at war with common sense, and daily observation, and every man’s own consciousness. What is family government; what is civil government; what is temptation, exhortation or persuasion; and what are the influences of the Holy Spirit; but the means, and the effectual means, of influencing the exercises of the human heart, and the conduct of human life? To deny the possibility of control by motives, without destroying free-agency, annihilates the moral government of God, and is atheism. It shuts him out of the world, and out of the universe, as moral governor. It blots out his laws as nugatory; emancipates every subject from his moral influence; and leaves him not an inch of territory on earth or in heaven, over which to sway the scepter of legislation. He must sit upon his throne as an idle spectator of all moral exercise and action; receiving no praise for what he has done for saint or angel. “By the grace of God I am what I am,” was a falsehood upon earth, and a lie that can never be repeated in heaven.

Natural and moral government may agree, also, as to the certainty of their influence. It may be as certain that an honest man will not steal, as if he was loaded with chains and could not move a finger; and it may be as certain that an intemperate man will drink to excess, when he has opportunity, as if the liquid were poured down his throat by irresistible power. But they differ entirely as to their subjects, and the manner of producing their results. Natural government is direct, irresistible impulse. Moral government is persuasion, and the result of it is voluntary action in the view of motives.

Free-agency cannot be conceived to exist, and probably cannot exist, in any other manner, than by the exhibition of motives to voluntary agents, the result of which shall be choice and action. The precise idea of moral government, then, is the influence of law upon the affections and conduct of intelligent accountable creatures.

II. I am to show that the scriptures are to be regarded as containing the laws of a moral government, revealed to illustrate the glory of God, in the salvation of man.

The glory of God is his whole character. The illustration of his glory, is the exhibition of that character to intelligent beings, as the object of supreme complacency and enjoyment. The plan of Redemption is the particular system of action, which the most high has chosen as the medium of illustration; and this plan is the system of moral laws contained in the Bible. That the Bible is to be regarded as revealing a system of moral laws, is evident from many considerations. The Most High has there revealed himself as a law-giver. His power, wisdom, and goodness, his justice, mercy, and truth, are exhibited not as abstract qualities, but as attributes illustrated by the laws and administration of a moral government. Man, the subject of these laws, possesses indisputably all the properties of an accountable agent, understanding, conscience, and the faculty of choice; and in the Scriptures, is recognized as accountable. Did the Most High create all things to illustrate his glory? It is a glory, which can be displayed only in the administration of a moral government. How can justice be manifested where there are no laws, and no accountable subjects? How can mercy be displayed where there is no transgression; or truth be illustrated where there is no intelligent mind to witness the accordance of declaration with fact, or of conduct with promises? The Most High is expressly denominated king, law-giver, and judge. The legislative, judicial, and executive power are in the same hands; and the Scriptures are denominated the law of the Lord, his statutes, his commandments.

The contents of the Bible illustrate its character as a revealed system of precepts and motives. There is the moral law in ten commandments; and its summary import comprised in two; and there is the gospel, no less than the law, composed of precepts enforced by sanctions. As a rule of life, it adopts the moral law; but as a system of salvation, it prescribes its own specific duties of repentance and faith, enforced by its own most glorious and fearful sanctions. Whatever instruction is contained in the Scriptures, historical or biographical, it is all directory, as a precept, or influential, as a motive to obedience. All the institutions of the Bible have for their object the preservation of truth in the mind, or the impression of it upon the heart as the means of restoring men from sin to holiness. The day of Judgment, as described by our Saviour, consummates the evidence that the Bible is to be regarded as embodying the laws of the divine moral government below. On that day, the graves open, and the dead, small and great, stand before God, and are judged according to the rule of action disclosed in the Bible, and the deeds done in the body.

If the Bible does not contain, in its precepts and doctrines, a distinct and precise meaning; it contains no meaning; it gives no illustration of the glory of God, no account of his will, of the state of man, of the character of the Saviour, or of the terms of life. A blank book of as many pages might as well have been sent down from heaven, for reason to scrawl its varied conjectures upon, as a bible whose pages are occupied with unmeaning or equivocal declarations.

II. If the Bible contain the laws of a moral government in the manner explained; then it is possible to ascertain, and to know that we have ascertained, its real meaning. It not only contains a precise meaning, but one, which being understood, carries with it the evidence of its own correctness. It is often alleged, that there are so many opinions concerning the doctrines of the Bible, that no man can know that his own belief is the true belief; and, on the ground of this supposed inevitable uncertainty, is founded the plea of universal charity and liberality:–sweet sounding words for universal indifference or universal skepticism! For who can be ardently attached to uncertainty; or who can believe any revealed truth with confidence, when his cardinal maxim is, that the doctrines of the Bible are obscure and uncertain?

But who is this, that libels his Maker as the author of an obscure and useless system of legislation, which no subject can understand, or, if he does, can have competent evidence of the fact?—so obscure, that they who discard it wholly are little incommoded by the loss, and entitled to little less complacency than those who grope in vain after its bewildered dictates;–so obscure, that those who err, are more entitled to pity than to condemnation, and afford as indubitable evidence of fidelity in examination, and sincerity, in believing wrong; as those do, who by mere accident have stumbled on the truth without the possibility of knowing it.

This is indeed a kind hearted system in its aspect upon man; but how tremendous its reaction upon the character of God. Why are his revealed Statutes with their sanctions so obscure? Because he could not make them intelligible? You impeach his wisdom. Why then are they so obscure? Because he would not make them plain? You impeach his justice; for he commands his truth to be loved and obeyed;–an unjust demand, if its obscurity prevent the possibility of understanding it.

But it is demanded; How can you know that your opinion, among various conflicting opinions, is exclusively correct? You may believe that you are right, but your neighbour believes that he is right; and you are both equally confident and both appeal to the Bible. If the question were, how can I cause my neighbour to know that his opinion is incorrect and mine true; I should admit, that the difficulty, in given cases, may be utterly insurmountable. But to suppose, because I cannot make others perceive evidence which I perceive, that, therefore, my perception brings with it to me, no evidence of truth, implies, that there is no such thing as moral certainty derived from evidence; and that the man, who believes a fact upon evidence, has in himself no better ground of certainty than the man, who believes a fact without evidence, or even against evidence: that a reality, actually seen and felt to be such, affords to him who either sees or feels, no higher evidence of its existence, than a fiction, supposed to be a reality, affords of its actual existence. That is, a non-existence, without any evidence of being, may possess as high claims to be recognized as a reality, as a real existence, supported by evidence: for error in competition with truth is in fact a non-existence opposed to a reality.

Now the man, who holds an erroneous opinion, may be as confident of its truth, as the man who believes the truth; but is there, in the nature of things, the same foundation for his confidence? Has not the man, who sees the truth and its evidence, knowledge, which the deceived man has not? If you deny it, you deny first principles; you annihilate the efficacy of evidence as the basis of knowledge, and introduce universal skepticism. Every vagary of the imagination and every prejudice of the heart are as likely to be true without evidence, as points most clearly proved.

But if the confidence in truth and falsehood be the same, how can you be sure that you do see what you think you do; and that what you think you do; and that your opinion is not the mental deception? It is the same question repeated, and I return the same answer—I can know, if my opinion be correct, that it is so; because evidence seen and felt creates a moral certainty; because reality affords evidence above fiction, and existence affords evidence above non-existence. What has fiction to do to annihilate realities; and what has deception to do to cancel the perceived evidence of truth?

If you would witness the folly of the maxim, that truth and evidence afford no certainty amid conflicting opinions, reduce it to practice. The man who dreams is as confident that he is awake, as I who in reality am awake. Is it then doubtful which is awake; and utterly impossible for me to decide whether I dream, or my neighbour? The lunatic feels as confident that he is a king, as the occupant of the throne. The royal personage then must hold his thoughts in equilibrio; for here is belief opposed to belief, and confidence opposed to confidence. Do you say that the man is insane; but he believes all except himself to be insane; and who can tell that any man is in his right mind, so long as there is a lunatic upon earth to question it?

Godwin taught, and many a robber has professed to believe, that private property is an encroachment upon the rights of man. If your purse, then, should be demanded upon the highway, you may not refuse; for the robber believes his opinion about liberty and equality to be true, and you believe yours to be true, and both are equally confident. It is also a speculative opinion about which you differ, and one concerning which great men have differed, and perhaps always will differ. You need not reason with him; for, since you cannot be sure that you are right, how an you expect to make him know what you cannot know yourself? And, as to the law of the land, it would be persecution for a mere matter of opinion to appeal to that, even if you could. Besides, how could a court and jury decide what is true amid conflicting opinions on the subject? And what right have they authoritatively to decide, and bind others by their decisions, upon matters of mere speculation?

But how shall a man help himself, who really and confidently believes falsehood to be truth? Just as other men in other cases help themselves, who by folly or crime have brought calamities upon themselves. How shall a man help himself, who has wasted his property?—Perhaps he never will, but will die a beggar. How shall a man help himself, who through negligence or crime has taken poison and fallen into a lethargy? He may never awake. Believing falsehood to be truth may be a calamity irretrievable. The man must perish, if the error be a fundamental one, unless he renounce it and embrace the truth; and his case, in many instances, may be nearly hopeless. Instead of its being a trivial matter what our opinions are;–it is easy by the belief of error to place ourselves almost beyond the hope of heaven, in the very region of the shadow of death. What a man may do and ought to do, is one thing; and what he will do may be fatally a different thing. “Their eyes have they closed, lest at any time they should see and be converted, and I should heal them.”

III. If the Bible contain a system of Divine Laws, it is easy to perceive the high importance of revealed truth. It exhibits the divine character as the great object of religious affection. It embodies the precepts of the divine moral government; prescribes the affections to be exercised, their nature, object, and degree, and the actions by which they are to be expressed. It embodies all the motives by which God restrains his subjects from transgression, and excites them to obedience. It exhibits the character of man as depraved and lost; and discloses by whom, and by what means, an atonement has been made, and upon what terms pardon may be obtained. It is the means employed by the Spirit of God to awaken the sinner to a sense of his danger, and to bring home to his heart a deep conviction of his guilt and just condemnation. It is by the Truth, that the Spirit of God converts the soul, and sanctifies the heart, and sheds abroad the love of God, and awakens hope, and diffuses peace and joy.

The truths of revelation are as important as the illustration of the glory of God, and as the happiness of the holy universe, caused and perpetuated by their instrumentality through all his dominions, and through eternity. In the view of this subject, how irreverent the maxim. “No matter what a man believes, provided his life be correct:” a maxim, which abrogates the law of God in its claims upon the heart; annihilates the doctrine that intention decides the moral nature of actions, and the doctrine that motives are the means of moral government; and reduces all obedience to the mere mechanical movements of the body. No matter whether a man believe or disbelieve in the divine existence; whether he love or hate the Lord; whether he trust in or despise the Saviour; whether he repent of his sins or remain incorrigible; whether his motives to action be good or bad. If the mere motion of his lip, hand, and foot, be according to rule, all is well. Is not this breaking the bands of Christ, and casting away his cords? Is it not saying to Jehovah, “Depart from us, for we desire not the knowledge of thy ways?” With equal irreverence, it is alleged to be of little consequence what a man believes, provided he be sincere. But what is sincerity? It is simply believing as we profess to believe; and the unblushing avowal is, that the Bible is a worthless book, no better than the Alcoran, or the fictions of Paganism, or the superstitions of Popery. “No matter what a man believes, provided he does believe it!” Falsehood, then, believed to be true is just as pleasing to God, and just as salutary in its influence upon man, as the combined wisdom and goodness of God, disclosed in his own most holy code of revealed laws.

The merest fictions of the brain, or the most malignant suggestions of a depraved heart, are as salutary as the laws of God. What authority have you for this opinion? Where have you learned that Jehovah is regardless of his honour, and the manifestation of his glory; is regardless of his laws, and their sanctions; is regardless of man, and the object of his affections, and the means of his salvation? You have not learned this from the Bible. You are an infidel, if you believe the maxim that it is no matter what a man believes provided he be sincere; and if you believe in no God but such an one as this maxim supposes, you are an atheist. The great end of all the works of Jehovah, according to the Bible, is the manifestation of his true character to created intelligences as the source of everlasting love, and confidence, and joy, and praise. But this glory is not an object of direct vision: It is manifested glory; and the system of manifestation is the plan of Redemption disclosed in the Bible, and carried into effect by the Spirit of God in giving efficacy to revealed truth in the sanctification and salvation of man. It is by the church, that he makes known to principalities and powers, in heavenly places, the manifold wisdom of God. Without just conceptions, then, of revealed truth, the true character of God is not manifested, and cannot of course become an object of affection, or source of joy. Erroneous conceptions of revealed truth, eclipse the glory of God, in its progress to enlighten and enrapture the universe. They propagate falsehood concerning God through all parts of his dominions where they prevail, undermine confidence, annihilate affection, and extinguish joy. They arrest the work of redemption; for moral influence is the influence by which God redeems from sin, and revealed truth embodies that influence. When that light has been wantonly extinguished, God will not sanctify men by the sparks of their own kindling; or hold those guiltless who have perpetrated the deed. The most High is not regardless of the opinions his subjects form concerning Him. He has given them the means of forming just conceptions of his character; and if they wantonly libel their Maker to their own minds, or to others, He will punish them. He is not indifferent what objects we regard with supreme affection, and as our supreme good. He has exhibited his true character, and commanded us to love Him; and, if we pervert his character and worship other gods, He will punish the idolatry. He is not regardless of his own laws, nor of the moral influence by which He restrains and sanctifies. He has made them plain; and it is at our peril, if we falsify them, and break their force upon our own minds, or the minds of others. “Woe unto them that call evil good, and good evil, that put darkness for light, and light for darkness, that put bitter for sweet, and sweet for bitter.” “As they did not like to retain God in their knowledge, God gave them over to a reprobate mind.”—“Whose coming is after the working of Satan, with all deceivableness of unrighteousness in them that perish, because they received not the love of the truth, that they might be saved:–And for this cause, God shall send them strong delusions, that they should believe a lie, that they all might be damned who believe not the truth, but have pleasure in unrighteousness.” Do these passages teach, that it is of no consequence what a man believes, provided he is sincere?

IV. If the Scriptures contain a system of Divine Laws; then, in expounding their meaning, their supposed reasonableness or unreasonableness is not the rule of interpretation.

It is the opinion of some, that the Scriptures were not infallibly revealed in the beginning; and that they have since been modified by art and man’s device, until what is divine can be decided, only by an appeal to reason. What is reasonable on each page is to be received, and what is unreasonable is to be rejected. The obvious meaning of the text, according to the established rules of expounding other books, is not to be regarded; but what is reasonable, what the text ought to say, is the rule of interpretation. Every passage must be tortured into a supposed conformity with reason; or, if too incorrigible to be thus accommodated, must be expunged as an interpolation.

It is admitted that without the aid of reason the Bible could not be known to be the will of God, and could not be understood. Reason is the faculty by which we perceive and weigh the evidence of its inspiration, and by which we perceive and expound its meaning. Reason is the judge of evidence, whether the Bible be the word of God; but that point decided, it is the judge of its meaning only according to the common rules of exposition.

Deciding whether a law be reasonable or not, and deciding what the law is, are things entirely distinct; and the process of mind in each case is equally distinct;–The one is the business of the legislator, the other is the business of the judge.

In making laws, their adaptation to public utility, their expediency, and equity, are the subjects of inquiry; and here the reasonableness or unreasonableness of a rule must decide whether it shall become a law or not. But when the Judge on the bench is to expound this law, he has nothing to do with its policy, or utility, or justice. He may not look abroad to ascertain its adaptation to the public good, or admit evidence as to its effects. He is bound down rigidly to the duty of exposition. His eye is confined to the letter, and the obvious meaning of the terms, according to the usages of language.

But what is meant by the terms reasonable, and unreasonable, as the criterion of truth and falsehood? It cannot be what we should naturally expect God would do; for who, beforehand, would have expected, under the reign of infinite power, wisdom, and goodness, a world like this; a world full of sin and misery. It cannot be what is agreeable to our feelings or coincident with our wishes; for we are depraved; and the feelings of traitors may as well be the criterion of rectitude concerning human governments, as the feelings of the human heart respecting the divine.

The appropriate meaning of the term reasonable, in its application to the Laws of God, is the accordance of his laws and administration with what is proper for God to do, in order to display his glory to created minds, and secure from everlasting to everlasting the greatest amount of created good.

But who is competent, with finite mind and depraved heart, to test the revealed Laws and Administration of Jehovah by this rule? To decide upon this vast scale whether the doctrines and duties of the Bible, and the facts it discloses of divine administration are reasonable or not, the premises must be comprehended. God must be comprehended; the treasures of his power, the depths of his wisdom, the infinity of his benevolence, his dominions must be comprehended; the greatest good must be known, and the most appropriate means for its attainment. All his plans must be open and naked to the inspection of reason, the whole chain of causes and effects throughout the universe and through eternity, with the effect of each alone, and of all combined. Reason must ascend the throne of God; and, from that high eminence, dart its vision through eternity, and pervade with steadfast view immensity, to decide whether the precepts, and doctrines, revealed in the Bible come in their proper place, and are wise and good in their connection with the whole; whether they will best illustrate the glory of God and secure the greatest amount of created good in a Government which is to endure forever. But is man competent to analyze such premises, to make such comparisons, to draw such conclusions?

If God has not revealed intelligibly and infallibly the laws of his government below; man cannot supply the defect. If holy men of old spake not as the Holy Ghost gave them utterance, but as their own fallible understandings dictated; and if, since that time, the sacred page has been so corrupted, that exposition according to the ordinary import of language fails to give the sense, then it cannot be disclosed; and the infidel is correct in his opinion that the light of nature is man’s only guide. The laws of God are lost, the Bible is gone irrecoverably until God himself shall give us a new edition, purified by his own scrutiny, and stamped by his own infallibility.

Apply these maxims concerning the fallibility of revelation, and the rule of interpretation to the laws of this commonwealth. The wisdom of your ablest men has been concentrated in a code of laws: But these laws, though perfect in the conception of those who made them, were committed to writing by scribes incompetent to the duty of making an exact record, and the publication was entrusted without superintendence to incompetent workmen, who by their blunders, honest indeed, but many and great, defaced and marred the volume: to which add, that at each new edition every criminal in the state had access at each new edition every criminal in the state had access to the press and modified the types unwatched, to suit his sinister designs. What now is your civil code?—You have none.—The law is so blended with defect and corruption, that no principles of legal exposition will extricate the truth. What then shall be done? Your wise men consult, and come to the profound conclusion, that such parts only of the statute book as are reasonable, shall be received as law; that what is reasonable, each subject of the commonwealth, being a reasonable creature, must decide for himself; that the judges, in the dispensation of justice, shall first decide what the law ought to be, and thence what it is; and that such parts of the statute book, as by critical torture, cannot be conformed to these decisions, shall be expunged as the errata of the press, or the interpolation of fraud. And thus the book is purified, and every subject, and every judge is invested with complete legislative power. Every man makes the law for himself, and regulates the statute book by his own enactments.

But is this the state of God’s government below? Is the statute book of Jehovah annihilated, and every man constituted his own lawgiver? The man who is competent to decide, in this extended view, what is reasonable, and how, in relation to the interests of the universe, the Bible ought to be understood, is competent without help from God to make a Bible. His intelligence is commensurate with that of Jehovah; and, but for deficiency of power, he might sit on the throne of the universe, and legislate and administer as well as He.

The mariner who can rectify his disordered compass by his intuitive knowledge of the polar direction, need not first rectify his compass, and then obey its direction; he may throw it overboard, and without a luminary of heaven, amid storms, and waves, and darkness, may plough the ocean, guided only by the light within.

V. From the account given of the scriptures, as containing a system of moral laws, it appears that a mystery may be an object of faith, and a motive to obedience. The idea of a mystery in legislation has been treated with contempt, and the belief of a mystery has been treated with contempt, and the belief of a mystery has been pronounced impossible. No man, it is alleged, can be truly said to believe a proposition, the terms of which he cannot comprehend. Hence has emanated the proud determination to subject every doctrine of Revelation to the scrutiny of reason, and to believe nothing which exceeds the limits of individual comprehension. Now it is conceded, that in the precept of a law, mystery can have no place; it must be definite and plain. It is also conceded, that no man can believe a proposition, the terms of which he does not comprehend. But the mysteries of revelation are not found among its precepts; and the proposition which is the precise object of faith is never unintelligible, but is always definite and plain.

A mystery is a fact, whose general nature is in some respects declared intelligibly; but whose particular manner of existence is not declared, and cannot be comprehended. The proposition which declares the mystery has respect always to the general intelligible fact, and never to the unrevealed, incomprehensible mode of its existence. A mystery, then, is an intelligible fact, always involving unintelligible circumstances, which cannot of course be objects of faith, in any definite form.

Allow me to illustrate the subject by a few examples. God is omnipresent. This proposition announces a mystery. The general intelligible fact declared is, that there is no place where God is not. The mystery is, how can a spirit pervade immensity.

That the dead are raised, is an intelligible proposition; but “how are the dead raised up, and with what bodies do they come” are the attendant mysteries; “It is raised a spiritual body.” The intelligible proposition here is, that the materials of the natural body are reorganized at the resurrection, in a manner wholly new, and better adapted to the exigencies of mind; but in what manner the spiritual body is organized, and how it differs from the natural body, are the attendant unexplained circumstances.

Take one more example; the doctrine of the Trinity. The Scriptures revel that there is but one God. They also reveal a distinction in the manner of the divine existence, which lays a foundation for mutual stipulations and distinct agencies in the work of redemption: which distinction is expressed by the names Father, Son, and Holy Ghost.

Now the proposition that there is but one God is intelligible. The proposition, that there is a deviation in the manner of the divine existence from the exact unity of created minds, is as intelligible as if the nature of this deviation were subjected to the analysis of reason, and brought within the limits of human comprehension. That this deviation from the exact pattern of unity, as exhibited in the human mind, is such as lays a foundation for ascribing distinct names, attributes, exercises and actions to the Father, to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost, according to the obvious language of the Bible, is as intelligible a proposition, as if the precise nature of this distinction was unveiled to the scrutiny of the human understanding.

Will it be alleged, that, where distinction approaches so nearly to absolute distinctness and independency of mind, there can be no union that shall constitute them one God? To know this, you must be Omniscient, and comprehend the mode of the divine existence, and all possible modes of the existence of spirit. You must ascertain that there is but one possible mode of intelligent existence, and that, the precise mode of unity which appertains to the mind of man.

You must not only be unable to see how any other mode can be, but you must be able to prove that it cannot be. But are you competent to do this? How then do you know that the divine Spirit does not exist; and why undertake to decide that he cannot exist, in such a manner as illustrates all that is declared of his unity, as one God and all that is implied in the distinction of names, and in the intellectual and social intercourse, stipulations, and distinct agencies recognized in the plan of redemption.

The whole force of the objection against the resurrection of the body was, how decomposed matter could be reorganized in a different manner, and yet be the same body. The Apostle’s answer is, “thou fool,” cannot he who organized the body at first, organize it again? And after all that heaven and earth and sea have disclosed of his skill in the diversified organization of matter, do you presume to say that the materials cannot be reorganized, in a manner wholly new, and better adapted to the exigencies of spirit? And to every one who demands how the Supreme Intellect can be One, and in any sense Three, according to plain scriptural declaration, the same answer may be given. “Thou fool,” art thou Omniscient? Dost thou comprehend all possible and all actual modes of spiritual existence? Can there be no mind but after the exact pattern of human intellect, and dost thou see it, and canst thou prove it? Why then dost thou array thine ignorance against Omniscience, and exalt thy pride of reason above all that is called God?—There is no alternative but to claim the infallibility of Omniscience, and deny the possibility of any distinction in the manner of the divine existence, which shall lay a foundation for the language employed in the Scriptures: or to take the ground that no fact can be conceived to exist, or be proved to be a fact, whose mode of existence is incomprehensible, a position which destroys the use of testimony, and the possibility of faith. For the use of testimony is to establish the existence of facts, without reference to their mode of existence. But, according to this maxim, the fact itself cannot be conceived to exist in any form, unless the specific mode of existence be also comprehended. The evidence of its existence, therefore, is not testimony, but some intuitive comprehension of the manner how the fact exists; and the assent of the mind, that the fact does exist, is not faith, but intuition. Apply the maxim, and it will blot out the universe; for who can comprehend the fact of eternal uncaused existence. The fact then is not to be admitted, and thus we set aside the divine existence. Or if we admit a single mystery, and recognize the being of God; still we cannot take another step; for how can spirit create or move matter, or govern mind, and not destroy free-agency? It is a mystery; therefore there is no created world and no moral government. The sun formed by chance, placed himself in the centre, and the surrounding orbs, self-moved, began their ceaseless course. But how can this be? It is a mystery:–and therefore there is no sun and no revolving system. A mystery then may be an objet of faith; for the proposition which is the precise object of faith is always intelligible, though always implying the existence of unintelligible circumstances.

Nor are mysteries useless in legislation as motives to obedience. The Divine Omnipresence, though a mystery, is among the most powerful motives to circumspect conduct. And the resurrection of the body, and its mysterious change are urged by the Apostles as motives always to abound in the work of the Lord.

The doctrine of the Trinity pours upon the world a flood of light. The peculiar mode of the divine existence lies at the foundation of the plan of redemption, as unfolded in the Bible, and brings to view, as a motive to obedience, an activity of benevolence on the part of God, a strength of compassion, a depth of condescension, and a profusion of mercy and grace, in alliance with justice and truth, which no other exhibition of the mode of the divine existence can give. It illustrates the riches of the goodness of God, and awakens that love which is the fulfilling of the law, and that repentance, and gratitude, and active obedience, which the goodness of God, thus manifested, could alone inspire.

VI. If the Bible contain a system of divine laws, revealed and administered with reference to the salvation of man; then it is practicable to decide what are fundamental doctrines.

Those doctrines are fundamental which are essential to the influence of law as the means of moral government, and without which God does not ordinarily renew and sanctify the soul.

The following have been usually denominated fundamental doctrines.

The being of God; the accountability of man; a future state of reward and punishment without end; and a particular providence taking cognizance of human conduct in reference to a future retribution. Are not these fundamental? Could the laws of God have any proper influence without them? Take away the lawgiver, or the accountability of the subject, or the cognizance of crimes by the Judge, or future eternal punishment, and what influence would the Scriptures have as a Code of Laws?

To allege that the remorse and natural evil attendant upon sinning are the adequate and only punishment of transgression, is most absurd. Do the natural evil and remorse attendant upon the transgression of human laws supersede the necessity of any other penalty? Is the impure desire suppressed, or intemperate thirst allayed, or covetousness dismayed, or the hand of violence arrested, by the appalling influence of remorse? It is always a sanction inadequate, which the frequency of crime diminishes, and the consummation of guilt annihilates.

The idea that gratitude will restrain without fear of punishment, where the confidence of pardon precedes sanctification, is at war with common sense. Try the experiment. Open your prison doors, and turn out your convicts to illustrate the reforming influence of gratitude, without coercion or fear of punishment. The idea that future discipline, for the good of the offender, constitutes the only future suffering, regards sin as a disease, instead of a crime, and hell as a merciful hospital, instead of a place of punishment. But how suffering in a prison with convicts old in sin shall work a reformation, no past analogy seems to show. Prisons have never been famed in human governments for their reforming influence.

The eternity of future punishment, considering the invisibility and imagined distance of the retribution, and the stupidity and madness of man, is indispensable. If the certain fearful looking-for of fiery indignation without end, exert an influence so feeble, to restrain from sin; the prospect of a limited, salutary discipline will have comparatively no influence. Nor is eternal punishment unjust or disproportionate to the crime. If the violation of the law in time, deserves punishment; it will no less deserve it, though the crime be perpetrated in another world; for probation and hope are not essential to free-agency or accountability, and the incorrigible obstinacy of the rebel will not cancel the obligation of the law. Endless wickedness will deserve, and will experience endless punishment. The deeds done in the body will determine the character, and shut out the hope of sanctification. But the rebellion will hold on its course unsubdued by suffering, and will be the meritorious cause of eternal punishment.

The above truths are essential to the moral influence of legislation generally. There are others which are no less essential to the Gospel, as a system of moral influence, for the restoration of man from sin to holiness. These are indicated by the peculiar ends to be obtained by the Gospel. If overt action and continuance in well-doing were all; simple reward and punishment might suffice. But man is a sinner; his heart is unholy; and new affections are demanded. Those truths, then, are fundamental, without which the specific, evangelical affections can have no being. To fear, the exhibition of danger is necessary: to repentance, the disclosure of guilt: to humility, of unworthiness: to faith, of guilt and helplessness, on the part of man, and divine sufficiency and excellence, on the part of the Saviour. There is a uniformity of action in the natural and moral world, from which the Most High does not depart, and which is the foundation of experimental knowledge, and teaches the adaptation of means to ends. Fire does not drown; and water does not burn; and fear is not excited by sentiments which exclude danger; nor repentance, by those which preclude guilt; nor affectionate confidence, by those which preclude guilt; nor affectionate confidence, by those which exclude dependence or the reality of excellence in the object.

To secure evangelical affections, the following truths are as essential, according to the nature of the human mind, as fire is essential to heat, or any natural cause to its appropriate effect; the doctrines of the Trinity, and the atonement, the entire unholiness of the human heart, the necessity of a moral change by the special agency of the Holy Spirit, and justification by the merits of Christ, through faith. The entire unholiness of the heart is necessary to beget just conceptions of guilt and danger; the necessity of a moral change to extinguish self-righteous hopes, and occasion a sense of helplessness which shall render an Almighty Saviour necessary; the doctrine of the Trinity, as disclosing a Saviour, able to save, and altogether lovely; the doctrine of the atonement, to reconcile pardon with the moral influence of legislation; and justification by faith instead of works, because justification by works cancels the penalty of law, blotting out past crimes by subsequent good deeds, giving the transgressor a license to sin with impunity to day, if he will obey tomorrow, provided his acts of obedience shall equal his acts of disobedience.

That these doctrines are fundamental, is evident from the violence with which they have always been assailed. The enemies of God know what most annoys them in his government; and the points assailed clearly indicate what is most essential. The whole diversified assault has always been directed against one or another of the doctrines, which have been named in this discourse as fundamental; and has had for its object to set aside either the precept or the sanction of Law, and reconcile transgression with impunity.

One denies the being of the Lawgiver: another discards the Statute Book as a forgery: a third subjects the Laws of Jehovah to the censorship of reason, and adds and expunges till he can believe without humility, obey without self-denial, and disobey without fear of punishment: a fourth saves himself the trouble of criticism, by a catholic belief of all the Bible contains, without the presumption or fatigue of deciding what the precise meaning is: a fifth pleads the coercion of the decrees of God, and denies accountability, and hopes for impunity in sin. Some however deem it most expedient to explain away the precept of the law. To love the Lord our God does not imply any sensible affection, any complacency or emotion of the heart, but the rational religion of perception and intellectual admiration; and by the heart is intended not the heart, but the head. Others assail, with critical acumen, the penalty of the law. Punishment does not mean punishment, but the greatest possible blessing which Almighty God in the riches of his grace can bestow, considering the omnipotence and perverseness of man’s free-agency: and eternal punishment means a number of years, more or less, of most merciful torment, as the disease shall prove more or less obstinate.

In like manner, the attributes of God are regarded in the abstract, dissociated from every idea of legislation and administration, by reward or punishment. Goodness is good nature even to weakness; justice is bestowing on men all the good they deserve, without inflicting any punishment; and mercy is the indiscriminate pardon of those, whom it would be malignant and unjust to condemn. The goodness of God as a lawgiver, promoting the happiness of his subjects by holy laws and an efficient administration of rewards and punishments, is kept out of view. His character of Lawgiver is annihilated, and his glory as Moral Governor is shut out from the world, that man may sin without fear.

All representations of the character of man, at variance with the scripture account of his entire depravity, have for their object the evasion, in some way, of the precept or penalty of law. One does it by pleading his inability to obey the law of God; and takes his refuge from punishment in the justice of God while he continues in sin. Another pleads not guilty in manner and form as the scriptures allege. He denies the necessary coincidence of holiness in the heart with overt deeds, to constitute obedience, and pleads his good actions in arrest of God’s decision that “there is none that doeth good, no one one.” He denies that the heart is desperately wicked. If it were true of Adam a short space; the promise of a Saviour made his heart better, and has made all hearts better: and, if not yet very good, they are so good as not to need a special change; so good, that attention to the constituted forms of religion duly administered will, by God’s blessing, make them good enough, without farther care or perception of change, as sun and rain cause vegetation and harvest, when the seed is sown while the husbandman sleeps.

No supreme and perceptible love to God is recognized as obligatory, no deep sense of guilt, no painful solicitude about futurity, no immediate repentance or faith including holiness, and no sin as being committed; while repentance and faith are deferred for the slow operation of forms, in making the sinner better, by the unperceived grace of God. The Law with its high claims upon the heart, and the Gospel with its holy requisitions, are made to stand aloof; while the sinner, without holiness, by dilatory effort, prepares himself to repent, or by lip service and hypocrisy, prevails on the Most High to give him repentance unto life. The whole law and Gospel are thrown aside, and the whole duty of man is epitomized in the short sentence. Thou shalt sincerely use the means of grace as faithfully as thou art willing to use them; and, by the grace of God through the merits of Christ and thine own well-doing, thou shalt be saved.

In the same manner, are the terms of pardon divested of holiness to accommodate unholy hearts, reluctant to obey, and fearful of punishment.

Faith is intellectual assent to revealed truth, without holiness, and too often without good works; or it is believing that one is pardoned when he is not, and knows he is not, in order that he may be pardoned. It is anything but the affectionate confidence of the heart in the Saviour, and the unconditional surrendry of the soul to Him. The rapid river in its haste to the sea, is not more violent to sweep away obstructions or evade them, than the heart of man to remove or evade the humbling demand of immediate love, repentance and faith, as the terms of pardon.

But who are those who most bitterly inveigh against these doctrines which we regard as fundamental? Is it the most serious, the most devout, temperate, chaste, and circumspect class of men. Is it, judging from their lives, according to the Bible, the righteous, or the wicked, the church of God, or the world. For the righteous, according to the Scriptures, love the truth, and the wicked are opposed to it.

Now, if we find the most holy men, the most sedate, prayerful, and exemplary people, leaguing against these fundamental doctrines, grieving at their prevalence, and trembling at their effect in revivals of religion, and praying to God with tears to check their prevalence; we must abandon our confidence in these doctrines as the true system.

But if the Atheist, the Deist, the profligate, the votary of pleasure, and the sons of violence and lies, regard them with a common and almost instinctive aversion; then we must cleave to them as receiving from the world the distinctive evidence of their truth. They have always been charged with embodying blasphemy, and leading to licentiousness; and, if the charge be well founded, doubtless the blasphemer and impure have always been their advocates. But what is the fact? Are the irreligious and profane, the licentious, the worldly, and the vain, the advocates for the doctrines of total depravity, regeneration by special grace, justification by faith, and eternal punishment? With scarce an exception, they have been open-mouthed and bitter in their opposition, reviling both these doctrines and those who preach them. From age to age, they have been the song of the drunkard, and the standing topic of profane cavil and vulgar abuse. If good men, through misapprehension, have sometimes seemed to be opposed to them, they have given evidence that the opposition was only a seeming one; while in reality their hearts were in sweet accordance with them. But there are, it must be confessed, some, whose moral conduct may not have been profligate, who have given unquestionable evidence that the feelings of their hearts, as to these doctrines, were in exact accordance with those of the blasphemer and the profligate. These conclusions concerning the doctrines which are fundamental, are however controverted; we therefore appeal to a tribunal more infallible than our own judgment.

Those doctrines are fundamental, then, without whose instrumentality God does not renew and sanctify the hearts of men.

That man is unholy and unfit for heaven, without sanctification, is certain. That God is the agent, and truth the means of sanctification, is equally manifest; and the fact that some men do experience a change in the affections, both as to their moral nature and object, is as certain as any fact can be made by testimony. The witness testify to their own consciousness of such a change. Of this, they are as competent judges as of anything appertaining to their own experience. The fact alleged is, that once they loved the world more than God, and that from a given aera, more or less determinate, they have regarded the Lord their God with an interest and affection, wholly new in kind, and superior in degree, to their love for any other object. That they regard him with a good will, and complacency, and confidence, and gratitude, and joy, entirely unknown to them, until they became the subjects of this special change.

The number of the witnesses is overwhelming. To the testimony of the three thousand, renewed on the day of Pentecost, may be added the accumulated testimony of every intervening age, to this day; for there never was a time, even in the dark ages, when the doctrine of regeneration by the special agency of the Spirit was not confirmed, by the testimony of those who professed to have experienced this change.

The capacity of the witnesses for judging correctly allows nothing to be subtracted from the weight of their testimony, for it has not been the feebler sex only, and children, nor the poor and the ignorant; but men, aged, middle aged and young; men of affluence, of refined manners, of strong powers of intellect, of cool judgment, of firm fibre and undaunted courage, of extended knowledge and cultivated taste, of antecedent moral and immoral habits, who have united their testimony, with multitudes of every other class of society, and with the poor Hottentot and Esquimaux, and have declared that with them, old things had passed away, and all things become new.

The credibility of the witnesses as persons of veracity, would not be questioned on any other subject. To this we may add, that most of them conducted, before the alleged change, as if they did not love supremely the Lord their God; and afterwards, to their dying day, and in the hour of death, conducted in many respects, in a manner inexplicable upon any other supposition than the reality of the alleged change. It is surprising, that men as philosophers do not believe in the doctrine of regeneration, even though they had no confidence in the testimony of the Bible; for no fact in natural philosophy, no phenomenon of mind is established by evidence more satisfactory in its nature, than that which establishes the reality of a change of heart. No fact was ever proved in a court of justice, by a thousandth part of the evidence, which concentrates the testimony of millions to the fact of the actual renovation of the heart.

But do not the professed subjects of this change oftentimes apostatize? Sometimes they do; but more than ninety in one hundred do not apostatize. If the apostacy of ten be allowed in evidence against the reality of the change, the perseverance of ten balances the unfavorable evidence, and leaves the unimpeached testimony of eighty competent witnesses in favour of the blessed reality of the change. Upon testimony thus circumstanced, what would be the decision in a court of justice?

But it is alleged by some, that they have experienced all that appertains to this change of heart, and know it to be vain. That they may have experienced fear and trembling, such as the faith of devils inspires; and that these fears may have been succeeded by composure and joy, such as the hope of the hypocrite affords; may be admitted. But “what is the chaff to the wheat, saith the Lord?” What is the blade without root that withereth, to that which beareth fruit; the plant, which our heavenly Father has planted, to that which he taketh away because it is unfruitful; the lamp without oil that goeth out, to that, which is replenished and shines with growing light to the perfect day? It is incredible, that a heart, “deceitful above all things,” should be deceived; or that a heart, “desperately wicked,” should find no abiding pleasure in a religion, which it professed, but did not feel? “They went out from us, but they were not of us; for, if they had been of us, doubtless they would have continued with us.” It is not a new thing to resist the Holy Ghost; nor an impossible, nor (we fear) a rare event, by stigmatizing the work of the Spirit, to commit a sin, which shall never be forgiven. May God grant that the lightness, with which some men treat their past convictions of sin, and fears of punishment, do not prove at last the too sure indications of that hardness of heart and blindness of mind, to which, in his most tremendous displeasure, the blasphemed Spirit gives up the incorrigible sinner.

This moral change then, an indubitable fact, and indispensable to salvation, is, according to the Scriptures, accomplished by the power of God giving efficacy to truth.” Men are begotten again by the Gospel, born of incorruptible seed, which is the word of God, and sanctified by the truth. These blessed operations of the Spirit are experienced sometimes in solitary instances, like single drops of rain in a land of drought; and sometimes multitudes, almost contemporaneously, become the subject, first, of solicitude and conscious guilt, and afterwards of love, joy, and peace.

But it is also a matter of fact, and a tremendous fact it is, that, so far as these glorious displays of the renovating grace of God are accomplished by the instrumentality of preaching, they are exclusively confined to the exhibitions of these doctrines, which we have enumerated as fundamental. Where these are faithfully preached, the arm of the Lord is not always revealed in revivals of religion; though few ministers, in that case, spend their days without cheering interpositions of divine grace giving seals to their ministry. But where the doctrines of the Trinity, the entire unholiness of man, the necessity of regeneration by special grace, of the atonement, justification by faith, and future eternal punishment are not preached, or are denounced and ridiculed, there the phenomena of revivals of religion never exist, and solitary instances of regeneration are comparatively unknown; and where they do exist, they are regarded as the effect of delusion, or as proofs of a disordered intellect, rather than as indications of a merciful, divine interposition. The fact is unquestionable; and the statement of it is not invidious, because it is a subject of exultation on the part of those unhappy ministers, who discard the above doctrines, and whose people are the subjects of this melancholy exemption from the convincing and renewing operations of the Holy Spirit. In such places, the light does not even shine into darkness; but all is as the valley of the shadow of death. No jubilee trumpet is heard announcing a release from the bondage of corruption, and calling the slaves of sin into the glorious liberty of the sons of God. Such places are not the hill of Zion, upon which descend the rain and the dew of heaven; but they are the mountains of Gilboa, upon which there is no rain, neither any dew. They are the valley of vision, in which the bones are very many and very dry, and no voice is heard proclaiming, “O ye dry bones, hear the word of the Lord;” and no prayer is made, “Come, O breath, and breathe upon these slain, that they may live.” No voice announces a spiritual resurrection; and no influence from above begins it. All is silent as the grave, and motionless as death.

VII. If the Scriptures contain a system of divine Laws, then the doctrine of the entire depravity of man is not inconsistent with free-agency and accountability; for depravity is the voluntary transgression of the law; and the law is, “Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart;” and entire depravity is the constant refusal to love, in this manner, the Lord our God. It implies, not that men’s hearts have no kind sympathies, no social affections, or that these are sinful, or that their actions are all contrary to rule; but only, that they have no holiness, no supreme love to God, and therefore, do not with the heart obey, but do, with the heart, voluntarily and constantly, disobey the law. The principle assumed in the objection is, that if men will with the heart obey the law of God in part, then they are free-agents, and blameable for not obeying perfectly. But if they violate the law willfully and wholly, so as not to love at all, then they are not to blame. If a man regulates his temper according to the gospel one day, and the next indulges malignant dispositions, he is a free-agent, and liable to punishment; but if he exercise no right affections, and every imagination of his heart be only evil, then the wrath of heaven must sleep, for the man has become too wicked to be the subject of blame. If a subject violate one half the laws of the land, he may be justly punished; but if he should press on and tread them all under foot, his accountability expires, and he may bid defiance to retribution.

VIII. The view we have taken of the Scriptures as containing a system of divine Laws, illustrates the obligation to believe correctly and cordially, the fundamental doctrines of the Bible, and the criminality of error on these subjects.

It is a favorite maxim of some, that men are not accountable for their opinions, with respect to the doctrines of revelation:–Because there is no specific command that this or that doctrine shall be believed:–Because they are so obscurely revealed that no blame can attach to misunderstanding them:–Because no one doctrine is absolutely indispensable to salvation:–Because the doctrines of the Bible are subjects of mere theoretical speculation, of no practical influence:–and, Because belief and disbelief are not voluntary, but the mechanical and unavoidable result of evidence, or want of evidence.

It is admitted, that there is no specific and formal command, that the doctrine by the Trinity, or total depravity, or regeneration of special grace, or justification by faith, or eternal future punishment, shall be believed; for these come under the head of motives or sanctions; and who ever heard of a special enactment requiring subjects to believe the declarations of a lawgiver, with respect to the sanctions of law? The obligation to understand and believe the doctrines of the Bible, is involved in the nature of the Bible as a book of law. The subjects of Jehovah are bound to understand the laws of his government, under which they live, and to believe his declarations, without a special enactment, and a subjoined penalty. They are bound to understand the character of God, the great Object of religious affection, and Foundation of moral obligation, and to act with such a temper, and under the influence of such motives, as God has required. But a law is never understood, whose precepts only are recognized, and whose sanctions are unknown. The character of God is not correctly and adequately disclosed by the precepts only of his Law; and the motives to obedience, and the principles of holy action are found no where but in the doctrines of revelation. If men, as accountable creatures, are bound to act as God commands; they are bound to understand those doctrines, which disclose the principles and motives of action; and this the Scriptures, in general terms, do command expressly and often. The command is reiterated in various forms to know the truth, a term comprehending the whole revealed system: to love the truth, not a part, but the whole truth, which is the Word of God: and to obey the truth, which is to believe what God has revealed, and to do what God has commanded, with the temper, and under the influence of the motives, which He has disclosed as principles of holy action.

To say, that the doctrines of the Bible are so obscurely revealed, as to supersede the possibility and the obligation of understanding them, is blasphemy. It is ascribing to Jehovah folly, or injustice, or both. It is annihilating the Bible, as a system of moral law; for precepts, without intelligible sanctions, are not moral government. Government lies in the motives revealed; and, if these cannot be understood, they are not revealed, and God does not administer a moral government except by the feeble impulse of the light of nature. And thus we land in infidelity.

The maxim, that no one doctrine of the Bible is absolutely indispensable to salvation, and the inference, thence drawn, that truth is useless and error innocent, is a sophism. It is drawing general conclusions, from particular premises. For suppose, that no one doctrine subtracted from the system, all the rest remaining and being cordially believed, would exile the soul from heaven. What then? Does it follow, that the disbelief and rejection of the whole system would not be fatal? What if it be true, that no one kind of nutriment is absolutely indispensable to human life; does it thence follow, that all nutrition may be safely dispensed with? What if no one poison be so active, but that a very little may be received into the system consistently with life? Does it thence follow, that poisons are harmless, are nutritious, and may be safely employed as a substitute for bread? The fact is, that those, who discard the doctrine of the Trinity, discard usually every other fundamental doctrine. Their system is not merely different from, but opposite to that denominated orthodox; so that if one be true, the other is false; if one be sincere milk, the other is poison. Nor does it follow that, provided a real Christian might, without believing some particular doctrine, possibly attain to heaven, he could therefore dispense with it without injury. Much less does it follow, that because a Christian may not be absolutely destroyed, by some erroneous opinion, that therefore an impenitent sinner may safely adopt it. An error which may not suffice to destroy spiritual life in a believer, may be decisive to prevent the commencement of it, in the heart of an impenitent sinner. Thousands may die a death eternal, by the influence of an error, under the operation of which, a Christian may possibly drag out a meager spiritual existence.

The opinion, that the doctrines of revelation are matters of mere speculation, of trivial practical influence, is a position at variance with the principles of law, with the constitution of the human mind, and with universal fact. It is not true of the principles of natural science, that they are mere matters of speculation, and of no practical influence on man. It is the practical influence of the sciences, which constitutes their utility. They exert a powerful influence, in the formation of the human character, and the regulation of human conduct. The whole course of the daily business of the world moves on by the illumination and potent energy of the sciences.

Much less is it a fact, that truth, contained in moral laws, has no influence. It is here, that the kind of truth is precisely that, which is most adapted to move free agents, and comes to the understanding, and conscience, and heart, with a designed concentration of influence, surpassing all other influence but that of direct physical impulse. The whole motive in legislation lies in the sanctions of law; and these have their influence through the medium of opinion. The motive to obedience is, as the opinion concerning it is. If that be correct, the true motive is presented to the mind; if incorrect, the intended motive is thrust aside, and another substituted. To say, that the doctrines of the Bible embodying and presenting to the mind of man that moral influence, by which God governs him as a free agent, and an accountable creature, are mere abstract speculations, of no moral influence or practical effect; is charging God with incompetency, in legislation; and disrobing him of his character of Moral Governor; and destroying the accountability of man; and blotting out the light of the glory of God, as it would otherwise be displayed in his works of providence and grace. But upon what authority is it alleged, that the doctrines of the Bible have no practical influence? Does opinion in human governments, concerning the lawgiver and the sanctions of law, exert no influence upon the character and conduct of man? Why then should the laws and sanctions of the government of Jehovah exert no influence, so that believing or not believing its fundamental truths shall have no effect? Doctrines in religion do exert a powerful influence. Have the doctrines of the Alcoran proved themselves idle theories, of no practical influence; or the doctrines of Paganism; or the doctrines of Popery? Have the doctrines of Calvin and Arminius no effect, or precisely the same effect? Why then oppose the one and eulogize the other, when both are equally good, or equally useless?

No truth in legislation, human or divine, is merely speculative; however it may appear such. What can be apparently more exclusively speculative than the opinion of the Gnostics, that all moral impurity lies in matter? But from this opinion, as a fountain, flowed the denial of the human nature and death of Christ, of the resurrection of the body, the celibacy of the clergy, the doctrine of penance and purgatory, and the host of cruelties and fooleries, which have taxed and tormented the world. Travel over benighted Asia, and witness the operation of the same opinion in the ablutions of the Ganges, and the self-inflicted torture of devotees to subdue the sin, which is in matter, and render the spirit pure and acceptable to the gods.

That Mahomet is the true prophet is a speculative opinion; but it has carried fire and sword in its course, and ruled the nations with a rod of iron, and dashed them in pieces as a potter’s vessel.

That the Pope is the successor of Peter, and universal and infallible bishop, is a matter of mere opinion; but it is an opinion, which has immured the nations of Europe in a dungeon, and bound them in chains, and almost extinguished the human intellect.

They are mere opinions, that there is no God; that the end sanctions the means; and that death is an eternal sleep: but fire, and blood, and wailing, and gnashing of teeth, have attended their march over desolated Europe. Considering man as an animal, the atheists of the French revolution destroyed his life with as little ceremony, as they would crush an insect. The fact is, that among moral agents, opinions respecting law and the sanctions of law, are principles of action; and no great aberration from rectitude in practice can be named, with respect to public bodies or individuals, which is not caused or justified by some false opinion. The opinion, that belief and disbelief are mechanical, to the exclusion of all influence of the heart, of interest, passion, and prejudice, is the consummation of folly.—Evidence may be so powerful, as to render incredulity impossible; and so feeble, as to render belief impossible. But an entire temperate zone lies between these two extremes, in which inclination and aversion, passion and prejudice, exert as decisive an influence upon the understanding, as evidence itself. If not, whence the maxim, that no man may judge in his own cause? Is it because all men are dishonest? Or is it because interest is known to pervert the judgment even of honest men? Whence all the unmeaning talk about sincerity, and prejudice, and candour? Who ever heard of a sincere, unprejudiced, candid pair of balances? If the mind decides by scruples and grains of evidence, as the scales are balanced by weights; why may not the honest judge decide in his own cause? Can interest vary the weights in the balance? How can he help himself without perjury, though the weight of evidence should be against his interest? The fact is notorious, that inclination possesses a powerful influence over the judgment. Examination may be neglected on one side, and pushed on the other. The evidence in favour of our choice may be dwelt upon, and the eye be turned away from that which would prove an unpleasant fact.

It is practicable to suspend a decision; to resist conviction; to pervert arguments, which prove unwelcome truths; and even to forget them; and to treasure up for use those, which favour conclusions which we love.

The demonstrations of Euclid, if their result had been the doctrine of the Trinity, the total depravity of man, the necessity of regeneration, and future eternal punishments, would have produced as much diversity of opinion, and brought upon his positions as much contempt, and upon his book as much critical violence, as has been experienced by the Bible.

Erroneous opinions are criminal, because they falsify the divine character, and destroy the moral influence of the divine law; because they are always voluntary, the result of criminal negligence to obtain correct knowledge, or of a criminal resistance of evidence, or perversion of the understanding through the depravity of the heart; and because the belief of error is always associated with moral and criminal affections. It is never a mere act of the understanding; the heart decides, and is never neutral. If a truth be rejected, it is also hated; if an error be embraced, it is also loved. It is because men have no pleasure in the truth, but have pleasure in righteousness, that they are given over to believe a lie, and are punished for believing it, with everlasting destruction. The propagation of error is criminal, of course, because it is destructive to the souls of men, annihilating the influence of the divine moral government, and the means by which God is accustomed to renew the soul, and without which he does not ordinarily exert his sanctifying power.

IX. In the view of what has been said, how momentous is the responsibility of ministers of the gospel; and how aggravated the destruction of those, who keep back the truth, or inculcate falsehood. It is, as if a man, not content with his own destruction by famine, should extend the desolation, by withholding nutrition from all around him; or not content with poisoning himself, should cast poison into all the fountains, putting in motion around him the waters of death. If there be a place in the world of despair, of tenfold darkness, where the wrath of the Almighty glows with augmented fury, and whence, through eternity, are heard the loudest wailings, ascending with the smoke of their torment:–in that place I shall expect to dwell, and there, my brethren, to lift up my cry with yours, should we believe lies, and propagate deceits, and avert from our people the sanctifying influence of the Holy Spirit.—And if there be a class of men, upon whom the fiercest malignity of the damned will be turned, and upon whose heads universal imprecations will mingle with the wrath of the Lamb, it will doubtless, my brethren, be ourselves; if, blind guides, we lead to perdition our deluded hearers.

The present occasion requires that a more particular application of this discourse be made to the Pastor Elect, and to the Missionaries, who are about to be ordained to preach the unsearchable riches of Christ among the Gentiles.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!