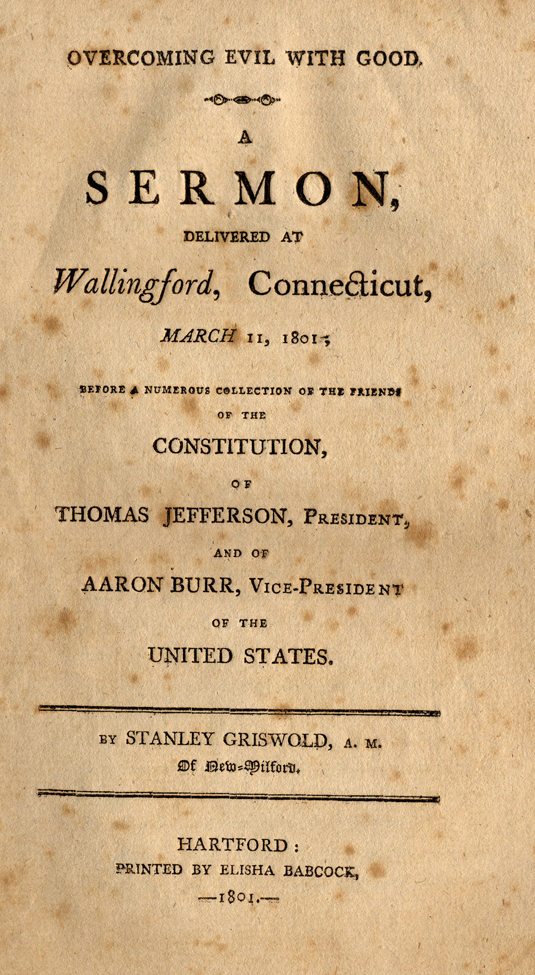

Stanley Griswold (1763-1815) served in the Revolutionary War and graduated from Yale in 1786. He also served as a pastor in Connecticut, as a newspaper editor (1804), as a United States Senator (1809), and as a judge for the Illinois Territory (1810-1815). Griswold preached this sermon in 1801, shortly after Thomas Jefferson was elected President.

A

S E R M O N,

DELIVERED AT

Wallingford, Connecticut,

March 11, 1801,

Before a Numerous Collection of the Friends

Of The

Constitution,

Of

THOMAS JEFFERSON, President,

And Of

AARON BURR, Vice-President

OF THE

United States.

By STANLEY GRISWOLD, A. M.

Of New-Milford.

A SERMON.

My RESPECTABLE AUDIENCE,

I CAME not hither to preach a system of party-politics, nor to excite nor indulge ravings of faction. I came in obedience to what I conceived to be the duty of a Christian and a patriot, to contribute my most earnest endeavors toward healing the unhappy divisions of our country.

Unfortunately some individuals are to be expected to be beyond cure, especially from such remedies as I shall apply, having drank down the poisonous virulence of party too copiously to admit of an easy recovery. But the citizens at large I cannot consider by any means in this predicament. They have ever been honest, are still honest, and desire nothing but to be honest.

If unhappily any individuals be past cure, the lenient remedies of the gospel, which I purpose to apply on this occasion, upon such will be thrown away. And for such nothing seems to remain but the severer applications of reproof and rebuke, which our Saviour occasionally exhibited to some in his day, while he spake to the multitudes with the greatest mildness and affection.

The method I have judged most proper to attain the object suggested, is to address a few considerations more particularly to the injured,–those of every denomination and description of sentiment in our country, who may have suffered wrongfully,–who have received wounds, and whose wounds have not yet forgotten to smart.

On such the peace and tranquility of our country, I conceive, very greatly depend. Their conduct and the course they adopt are to have no inconsiderable share in determining, whether this country is to settle down in quietness, and harmony to be restored to its citizens,–or whether it is yet to be agitated and shaken to its centre by the outrages of party.

Far would I be from impeaching the prudence, the patriotism or the Christianity of any who hear me. But it must be confessed, that we are all men, and men of like passions. Hence the necessity of repeatedly calling to remembrance the maxims of sound wisdom and the wholesome precepts of religion.—If by suggesting any of these I might contribute in some small degree to the felicity of my country, I could easily forego the ambition of appearing a political preacher on this occasion, and should consider myself well rewarded for any calamities which are past, or for any which are yet to come.

For pursuing the object proposed, the gospel of the benevolent Jesus affords themes in abundance. I have chosen that cluster of directions recorded.

YOU will at once recognize these precepts as being peculiar to our holy religion. However different they may be from the suggestions of flesh and blood, however contrary to the habits of unholy men or to the temper and practice of the world, on candid examination they will be found perfectly to consist with reason and sound philosophy,–and they bear excellently the test of experience.

If anything like policy and art may be conceived of the religion of Jesus Christ, the sentiment which runs through the passage we have read and is summed up in the concluding words, has an eminent claim to such a character,–overcome evil with good.—A harmless policy indeed! Yet the most effectual to accomplish the purpose designed. If the expression may be used, it is to revenge one’s self by benevolence,–it is to take vengeance by shewing kindness. Would you melt the obdurate heart of your foe, would you conquer him and lay him completely at your feet, the surest and most effectual way to accomplish it, is to do him good. Heaping upon him acts of kindness will have a similar effect as the smith’s heaping coals of fire upon a crucible whose obstinate contents he wishes to resolve; they will soften the injurious passions, they will melt down the heart of iniquity and enmity:–the first effect will be shame,–the next, reconciliation and love.

If this be not the directest way to conquer and get recompense for evil, it is certainly the most noble way. If it is not the most effectual, it is certainly the most godlike. This is the policy which God Almighty pursues toward our wicked race. This is the policy by which he conquers evil. We behold it in every morning’s sun which he raises upon our world. We behold it in every shower of rain which he sends upon our earth. We behold it more gloriously still in the face of Jesus Christ, the Saviour. It shines in the redemption he wrought out for sinners. It is conspicuous in the example he set for mankind. It distinguishes he system of morals which he taught. It is the glory of the gospel. Much did he urge it upon men as what alone could make them truly the children of their Father who is in heaven, and in pursuing of which only, they could be accounted genuine Christians and be said to do more than others.

This divine, this peaceful policy, my hearers, is what I wish now to urge upon you and upon myself; and could my voice extend through my country, it should be urged upon every citizen of America.—Would to God! an angel from heaven might descend at this important epoch, that he might fly through our land, and in strains of celestial eloquence impress upon all the injured in it, the glory of rendering blessing for cursing, of overcoming evil with good.—But I hope such have no need of miraculous means to convince them of the excellence of this gospel-policy and of the propriety and urgent necessity of putting it into eminent practice at the present time.

How desirable,–what an epoch to be remembered indeed would this be, if the wounds of our country might now be healed!—if henceforth she might bleed no more through intestine divisions, party-virulence, the ravings of faction and the mad acts of blind infatuation!—How happy, if mutual good will, heavenly charity and justice might once more be revived among us! How glorious, if the new order of things, as it is called, (I care not whose order nor what order it is called) might prove but the abolition of hatred, calumny, detraction, rigid discrimination, personal depression and injustice, and instead thereof restore the old order of social felicity, mutual confidence, benevolent and candid treatment which once distinguished the citizens of this country!—If one sincere desire is cherished by my soul, it is, that this happy old order of things might be restored,–that we might see an eternal end to the little, detestable maxims of party, and that the generous principles of the country might come forward and reign.—O Genius of America! Arise; come in all the majesty of thine ancient simplicity, moderation, justice; re-commence thine equal empire; drive the demon, Party, from our land: From henceforth let the order among us be thy order.

To insure such a glorious and most desirable order of things, my hearers, it is absolutely necessary that the injured among us, of whatever sentiment or character, should not think of revenging, should not think of revenging, should not think of retaining prejudices and a grudge against their fellow-citizens;–but if they revenge at all, let it be by benevolence. The only strife should now be, who can shew the most liberality and kindness,–who can do an enemy the most good. Let those who have been the most wronged, be the first to come forward and forgive. Let them bury in magnanimous amnesty, all that is past; and let them exhibit an example of what it is to be truly great,–great like a Christian,–great like God.

In this sublime policy of the gospel it is by no means implied, that we should be stoics, indifferent to good and evil, or that we should be reconciled to abuse, or that we should not rejoice and be thankful to heaven when we are delivered from it. Christianity was never designed to impair the noble sensibilities of our nature.

I profess no great skill as a politician;–nor does it belong to me to say, whether the sufferings which have arisen in our country from political causes, be now certainly at an end. But this I say, if there be well-founded reason to think they are at an end, if the present epoch in American affairs may really be considered as a deliverance on all hands from that unparalleled injustice, those overbearing torrents of abuse and accumulations of injuries, which for some time past have been heaped upon worthy and innocent men, and stained, I fear, the annals of our country beyond the power of time to obliterate,–if, I say, this be really the case and may be relied on as fact, then I declare the present occasion an occasion of great joy, deserving our most fervent gratitude to God.—And if it be an epoch to prevent still greater abuses from coming on, if it is to set back the tide of party-rage from reaching any farther, if it is to say to that boisterous deluge, which was rolling on in such terrible floods and already swept away much that is dear to us, Hitherto hast thou come, but no farther,–and here shall thy proud waves be staid,–if it is to prevent a relentless civil war from existing among us, whose flames, alas! lately appeared to be fast kindling, and in the apprehension of many, threatened by this time to have exhibited the awful scene of brother armed against brother—and garments rolled in blood through our land,–if henceforth nothing more is to be feared for personal character, liberty, life, the safety of our Constitution and government,–the peace of our country and our social happiness, then I declare it an epoch deserving eternal remembrance and the most heart-felt exultation before the God of heaven. God grant, it may prove such an area, and that our dear country may once more be happy.

But it requires no great political skill to see that all this in a measure depends on conditions: and one principal condition unquestionably is, that the injured forget their wrongs and be above revenge.

This leads me to suggest a few considerations to recommend the precepts in the text, or the gospel-policy of overcoming evil with good.

No one can doubt, that this is an eminent and very distinguishing part of the system taught by the author of our religion. Forgiveness of injuries, love to enemies, charity, a mild, inoffensive behavior, and even literally the rendering of good for evil, were themes much upon his tongue, continually urged and enforced by him. By the authority of our Lord, then, we are bound to practice these virtues.

And his example was strictly conformable to these his precepts. Never man endured so much contradiction of sinners against himself, so much enormous outrage, such monstrous abuse, as Jesus Christ endured. Yet never man behaved so perfectly inoffensive, or so unremittingly persevered in doing good.—He was reproached as a glutton and a drunkard, a friend and associate of publicans and sinners, a petulant fellow in community, an enemy to Cesar and all government, a low-bred carpenter’s son, a turner of the world upside down, a foe to religion, a vile heretic, a perverter of the good old traditions of the elders and the commands and institutions of the fathers, a despiser of the Sabbath, a blasphemer, a deceiver of the people, an agent of Beelzebub—But the time would fail me to tell of all the reproaches and all the hard names with which he was reviled.

Nor did his sufferings rest only in what pertained to reputation. His whole walk on earth was amid snares and plots craftily laid to take, not only his liberty, but his life. And everything was favorable to render those snares successful:–they were laid by a powerful hierarchy, seconded by the Rulers of the day, and the Evil One must come and render his aid. Much did he suffer:–but never did he manifest a single wish to injure them,–The people generally were more friendly to him:–they frequently flocked in multitudes around him, and often did they form a defence for his life which his foes dared not provoke.—But sometimes means were found to inflame them also, and set them against him. In these cases he was left alone to sustain the vengeance of an enraged world.—He could not live long. He was too honest and too good for this earth. At an early period of life he fell a victim to the powers combined against him.

But what was his conduct under these sufferings? What was his conduct even in that last trying hour, that hour of darkness, when perfect innocence was about to suffer indignities which should belong only to the foulest guilt? Now we should expect revenge, if ever. Now, that the measure of his injuries was full, might we not look for some capital blow to retaliate for the whole at once? Why did he not shake the earth out of its place and crumble his enemies to dust? Why did he not bid his waiting legions of angels empty the realms of heaven—fly and smite his abusive foes to destruction?—Good God! what do we see!—he goes as a lamb to the slaughter, and as a sheep before her shearers is dumb, so he openeth not his mouth! His dying breath wafts a tender prayer to the throne of mercy for his murderers, Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do!

Shall such an example shine before us, and not ravish us with its glories? Shall we boast such an Author of our religion, and not be ambitious to imitate him?—How do all the injuries which we endure and all our sufferings dwindle into nothing compared with those of our Master? And oh! How should all dispositions of vengeance melt away from our souls before the burning lustre of his example?

But let us look at the intrinsic merits of this conduct, thus exemplified by Jesus, and so eminently required by his precepts.—This conduct may be justified both on the ground of good policy and of moral obligation.

First, on the ground of policy. The apostle evidently suggests the idea of policy in these words,–for, in so doing, thou shalt heap coals of fire on his head. We have already explained this figure. It alludes to a smith’s heaping coals of fire upon a crucible, or any hard substance which he wishes to soften or solve. A very happy allusion to set forth the power of kind actions upon the hearts of our abusive enemies. If we wish to conquer them most effectually, this is the way to do it. We all, I presume, have witnessed somewhat of this in our intercourse with mankind. If we ourselves have ever unjustly abused another, for him to return us obliging and good actions upon it, makes us ashamed, and we soon desire to forget what we have done. This kind of conduct, well-timed and properly directed, is absolutely irresistible. It puts upon man the appearance of a superior being, and compels regard.—To repulse evil with evil, tends only to sharpen the hostile passions and to fix the parties in everlasting hatred. This is not conquest,–it is only continuing the battle without ever deciding the victory.

I suppose it likely, that it was on account of this peculiar feature in the character of Christ and his religion, that so many of his crucifiers were afterwards pricked in the heart and turned to be his followers, as we are told three thousand did at one sermon of Peter’s, on the subject of the crucifixion. And on the same account the religion of Christ made rapid progress in the world, so long as its supporters exhibited this its peculiar feature. But when they assumed the power of the state and the power of armies to assist the power of Christianity, and its advocates became fierce, revengeful, intolerant, then its spread was retarded, and even Mahometanism outstripped it in progress.

But secondly, the gospel-conduct in question, may be justified upon the ground of moral obligation. Our enemies and abusers, be they who they may, have something in them or pertaining to them which deserves our regard, and I will say, our love,–notwithstanding the malice and depravity which they may also possess.

In the first place they have existence. And is not existence valuable?—Think of annihilation! See how anxious all are to preserve their lives, not excepting the very brutes.—What is thus demonstrated to be valuable by every testimony around us, and by our own irresistible feelings, ought surely to be prized at some rate and to be treated accordingly.

They have also rational faculties. And are not these valuable?—Look at the idiot or at the delirious wretch! What an afflicting sight is the absence of mental faculties?—They are to be regarded, then, where they exist.

Our enemies possess immortal natures. This confers inestimable worth. The fly, that lives and sport a summer, is a being of small value. The brute, that protracts his life to a few years, is more valuable. But man, who is destined to live when the sun and the stars are no more, who is to travel onward and grow in excellence through eternal ages, possesses a value beyond all computation, beyond all conception. Our Saviour estimates a soul above the whole world. Is such an object to be dealt lightly with? Is he rashly to be consigned over to utter hatred, and shall every sentiment be expunged from our hearts which should excite us to consult his welfare?

They also have a capacity for virtue and happiness. However depraved at present, yet they are not beyond recovery. If malice now rankles in their hearts, yet their hearts are capable of being receptacles of benevolence. They are salvable creatures, restorable to virtue and felicity. Shall they be thrown away as good for nothing, and all regard be withdrawn from them, when this capacity is in them and they may yet be ranked with ourselves in dignity and bliss? Ought they not rather to be considered as a valuable machine, disordered truly, but capable of repair? Do we throw away our gold and silver utensils, because for the present they may have gotten out of order? Moral evil is but a disorder of the mind, and is removable. The evil should be hated; but the unhappy subject of it is still to be regarded. Our desire and endeavor should be to rectify,–not destroy.

The dignified nature of man, and his capability of being restored to virtue and felicity, were what rendered him in his sins an object of regard to his Maker, and procured for him the merciful provision of the gospel. What if God had treated our sinful race according to the dictates of enmity and hatred? Who would ever have found mercy?—No, he loved us notwithstanding we were enemies in our minds by wicked works. God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten son to die. Herein is love, not that we loved God, but that he loved us, and sent his Son to be the propitiation for our sins. God commendeth his love towards us, in that while we were yet sinners, Christ died for us. From the example of our Maker, then, as well as by looking directly at the subject, we see there is something in enemies and wicked men, which is a proper foundation for love, and demands benevolent treatment.

Another consideration which should commend our enemies to our affectionate regards is, they are our brethren, children with us of one great Parent, members together of one great family. Their blood is a branch of the same fountain which flows in our veins. They are “bone of our bone and kindred souls to our’s.”

—”Pierce my vein,”—says a poet,

Take of the crimson stream meandering there

And catechize it well:–apply thy glass,

Search it, and see now if it be not blood

Congenial with thine own.”—

They exercise all the functions which we exercise. They weep as we weep. They feel as we feel. They suffer as we suffer.—If some of the family are proud, selfish, disposed to be injurious and trample on the rights of the rest, let them be brought to know their places—but let them still be beloved. What is here suggested is the foundation of philanthropy, or universal benevolence, which unquestionably is the benevolence of the gospel, and what we all ought to entertain.

Thus on the solid basis of moral obligation rests the duty of loving and treating well our enemies.

I shall now mention a few considerations of another kind, which should make us extremely cautious how we indulge revengeful feelings toward those who may have abused us.

First of all, we ourselves are frail, fallible beings, and therefore may mistake the intentions of our fellow-creatures, misapprehend their motives, or may see their actions in a distorted form. Perhaps they are not so guilty as we imagine. Or it may be, through frailty we have offered unwarrantable provocation. In either of these cases revenge would be unjust.

We are further to consider, that our enemies and abusers are also subject to frailties. Great allowances are to be made on this account. The God of nature seems to have created some souls on an extremely little scale. Such are they who, capable only of being actuated by party-spirit, do nothing, think nothing, feel nothing, but just as party-spirit dictates. Some of this description have been known not to be able to hold common good neighborhood, nor Christian fellow-ship, nor to celebrate an anniversary festival, nor to communicate with their God, no, not even to hear a prayer, with one not of their particular party, be is character as bright as an angel’s. Shall we be disposed to revenge upon such little creatures?—pity, pity, nothing but pity is called for.

Others may become enemies and abusers merely because they mistake the intentions, the principles, the views of each other. They may see you through a false medium. Their enmity may be founded on some false report. They may be acted upon by an influence which they do not perceive;–may be led by the interested and crafty; may be deluded, deceived, excited by groundless alarm and cajoled in a thousand ways, which they themselves would despise, had they better information.—I verily believe, that more than one half of the feuds, animosities and enmities which afflict mankind, flow from these sources, rather than from any real ground of difference, or from downright malice of heart. I am certain this is the case in times of general party, when the people are roused up to oppress and abuse one another.—Oh! It is piteous to see the fatal fruits of this frailty,–to see honest and well-meaning people made to drink down potions of poisonous prejudice against their brethren for no cause,–to see them excited to baleful rage, made to vent reproaches, and ready to whet the sword of destruction, as against cannibals and monsters,–when the principles of both are identically the same, and all are seeking the same object,–only perhaps some party-name, devised and applied by knaves, with a plenty of misrepresentation, is the whole difference between them!—I am bold to say it, this of late years has been afflictingly the case in this country. People, whose real principles differ not one jot nor tittle, have been made most cordially to hate one another. The most genuine patriots have been anathematized by the most genuine patriots,–the truest whigs by the truest whigs,–the best republicans by the best republicans!—It was a pitiable scene.—But ought we to be disposed to revenge? Whoever thou art, of whatever party, that hast suffered in this way, if you hate these good people, you hate your best friends,–you hate your compatriots and real brethren. Moreover, they never hated you; they hated only a phantom in your stead,– a shade, an empty shade, which has been artfully raised up before them and called by your name.—The people at large are honest, and all the sin lies at the door of their deceivers. These may be rebuked sharply: they may be spoken to as the mild Jesus spake to the deceivers of the people in this day, Ye serpents! Ye generation of vipers! How can ye escape the damnation of hell? But to the people we should never speak in this manner. They were never spoken to thus by their friend Jesus. He always addressed the multitudes with respect and tenderness. And even their deceivers should not be devoted to hatred and ill offices. Like our Lord the genuine Christian will pray for them, if he can do no more.

When people are drawn by the designing into deep delusion and high party-rage, it is not to be expected that they all will come out together, that every one so soon as another will have the scales fall from his eyes to see clearly what has been the matter. This depends very much upon accident. The schemes of the crafty are often so deeply laid and so closely hedged about, that it requires years for them to come fairly out and be seen by the greater part of honest people. Often it is true of such schemes, “Longa est injuria,–longae ambages.” Many of the honest and unsuspecting will not be undeceived but by the unfolding of the scheme in serious and alarming facts.—But to some it may by accident be leaked out beforehand, perhaps from the very mouths of its authors. Or circumstances of a local and particular nature may conspire to convince some long before others. When this is the case, the first who are convinced will be thought hard of, and perhaps be calumniated and abused by their own brethren whose conviction is to come later. The schemers will endeavor to make this the case as much as possible, and will foment it by every means in their power. What is here observed may furnish an answer to those who sometimes ask one who differs from them, “How comes it that you know so much more than everybody else?” The true answer is, it comes by accident and various local circumstances, more than from any superiority of understanding or better principles of patriotism.—But it will be acknowledged, I think, that in these cases patience ought to be used, a very mild and gentle conduct ought to be observed. To revenge would be to revenge upon honest men.

We may vary a little the statement of this matter. The difference between honest people at the present day (and such I conceive the great body on both sides to be) is merely a difference of belief. Some individuals, to be sure may be most wicked and designing. But, it is idle to say, that the great body of people on either hand are not honest. They are honest, and most sincerely friendly to the Constitution and their country.—But one of one party believes there is a design on foot to overturn the Constitution and deprive the country of its liberties.—Another of another party believes no such thing. Whereas the latter would equally detest such a design and its authors, could he believe it were so.—Now shall men go to revenging upon one another merely for differences of faith, of belief? It would be reviving the worst doctrine of the dark ages.

Another consideration which should make us cautious not to indulge revenge is, that by so doing we pollute and injure our own souls. Revenge is a foul passion. To be overcome with it, is to be overcome with evil. Be it never so justly provoked, it hurts the temper; and if allowed to continue, will stop little short of entirely ruining it. Revenge is very properly pictured as a chief characteristic of the Infernals.—And the perfection of God is to be ever serene, good and forgiving.—When we can sincerely forgive our enemies, bless them and do them good, it is a token of great advancement in grace: for our Saviour considers this as the badge of Christian perfection, who in view of it says, Be ye therefore perfect, even as your Father who is in heaven is perfect.

As a further recommendation of this heavenly conduct, let me observe that whoever finds himself truly disposed to practice it, may have the consolation to think, that most probably he is in the right with respect to those things for which he is abused,–and that his oppressors are wrong. The sure signs of error are a rigid, illiberal conduct, persecution and abuse, a disposition to discriminate, depress and keep down by violence whatever is opposed, and to repay tenfold when we have it in our power. This kind of conduct from of old has always distinguished the advocates of error, and is a certain badge of it. Whereas truth never feels a necessity for these things,–but is always mild, meek, liberal, generous, friendly to moderation and the utmost fairness, asks only an equal chance to be heard, disdaining violence, sure to conquer by her own charms.—The Pharisees and chief-priests on one hand, and Jesus on the other, were perfect examples of the conduct which error and truth respectively inspire.

When parties exist, perhaps there is no better rule to determine which is nearest the truth, than to recur to the manner of their treating each other, and mark the quantity of abuse offered on either side. And among all the species of abuse, perhaps that of epithet is as sure a standard as any. Whichever party invents and applies odious epithets in the greatest abundance and of the most unfounded and scandalous import, may be presumed to be most out of the way.

The peaceful conduct under consideration may be recommended from the excellent effect which will ultimately attend it, although for the present moment it may be unsuccessful. When men are outrageously abused, they are wont to think, there was never anything like it before. And if their abusers prosper over them, they are apt to despair, and imagine all to be lost unless they resort to desperate efforts and oppose violence to violence.—But this is the short-sighted wisdom of the flesh. We at this late age of the world have reason to know better. Have not worthy men, the just, friends of truth, of righteousness, of liberty, of every the most laudable cause, suffered in every age? To omit the mention of others, did not the immaculate Jesus and his first followers suffer, as men never suffered? Yet, what was the effect? Did not the gospel rise, shake itself from ignominy and run triumphantly through the world; while their outrageous foes soon sank out of repute and out of remembrance? There is something in mankind which favors suffering merit, and will assist it in spite of all opposition,–something which approves of moderation and reasonable conduct, and condemns overbearing things. This is a laudable disposition in mankind, and where there is nothing special to repress the public will, it is certain to give eventual triumph to those who under abuse, conduct according to the maxims of Christ; it will in the end bring them, with their cause, out of all their troubles.

Finally, my hearers, if any of you (and I would address those of every description, sentiment and party) if, I say, any of you have experienced the odious effects of a system of conduct the opposite of the one we are considering, if you have experienced those effects in your reputation, business, profession, property or individual freedom,–if your indignation has been roused, or your contempt excited at any little, narrow, malevolent acts of men by which you have been attempted to be injured,–will you not still continue to detest, and forbear to adopt such a despicable system of conduct for your own? I beg to be considered as addressing all of every sentiment and character, who have been abused by any conduct opposite to the liberal precepts of Jesus.—Will you not abominate such conduct as you have been taught to do by your own hard experience? And will you not cleave to the generous, the manly, the godlike deportment prescribed in the gospel? Let me call upon your own sufferings;–let me appeal to your own past feelings,–your sorrow, your pity, your indignation, your scorn,–let me bring them all to your remembrance and conjure you by them, never, never to fall into a line of conduct which you so much disapprove. Never lost sight of those noble sentiments which you so much wished might have been shewn toward you. While they are fresh in your recollection, consecrate them,–santify them,–let them be eternally held sacred. Repay nothing of what you have received: nobly forbear. All things whatsoever ye would, that men should have done to you, do ye even so to them.

As it respects the public welfare and peace of the country, let me ask, Has not the monster, Party, raged long enough? Has he not marched like a bloody Cannibal through our land and glutted sufficiently his abominable maw? Has he not devoured enough of reputation, enough of honest merit, enough of our social peace and happiness? Has not brother hated brother, neighbor neighbor, citizen citizen, long enough? Is it not time to put an end to the wounds of society and to heal our bleeding country?—

I feel the more earnest on this occasion as I consider the present juncture of affairs most important. And I view myself addressing an audience composed in some considerable degree of a description of men through this country on whose prudent and wise conduct, much, very much depends to restore tranquility and happiness to our land.

Let me, then, bring to your view our bleeding country. Let me place her before you in all her deplorable plight,–torn and mangled with faction, poisoned with the venom of party,–wrecked with intestine hatred, strife, division, discord, and threatened with complete dissolution.—Before you she stands—To you she turns her eyes:–she implores your consideration:–she begs to be restored to her wonted dignity and happiness.—“Will you,” she cries, “introduce a system of party, personal depression and abuse, and tear my vitals asunder?—Oh! Remember Jesus, the friend of the world! His precepts will heal me. If you have been persecuted, I beseech you to bless:–if you have been despitefully used, pray for your abusers:–if you have been reviled, revile not again. Render to no man evil for evil, but contrariwise, blessing.—Overcome evil with good. Thus shall my reproach be wiped away:–thus shall my wounds be healed:–thus shall you and all my children be restored to happiness.”

Agreeably to these importunate cries of our country, suffer me to conclude with offering a few particular directions for the observance of all on whom anything depends relative to our country’s peace.

First of all, dropping on all hands every term and epithet of party,–I mean such terms and epithets particularly as originated in rancor, and have no foundation in reality,–carefully consult the ancient spirit of the country, see what its maxims were formerly, and what now are its genuine principles and wishes.—Whatever you find these to be, with them go forward and do the public will. Be not a faction within the country; but be the country itself. Let not your spirit be the passion of party; but let it be the public spirit. Let the Genius of America reign.

Give me leave to say, you will not mistake the ancient maxims of this country nor its present wishes, if you be stedfast, genuine Republicans.—If we recur to our forefathers we shall find them republican from the beginning. The spirit of freedom drove them from their native land and brought them to this then howling wilderness. Genuine principles of liberty were conspicuous in all their early proceedings. No greater liberty-men were ever seen in America, that Winthrop, Davenport, Hooker, Haynes, and all that band of worthies who, under God, were the means of our being planted here. Much has been said about the forefathers of New-England. The truth is, the leading, most distinguishing traits in their character were these two, Liberty and Religion. In both they were sincere, and prized them above all price. With beams extracted from these sources, their souls were illuminated and warmed.—They did not set up an outcry about liberty with an insidious view to root out religion and overturn its institutions: neither on the other hand did they make an outcry about religion and its institutions with a view to cover over an insidious design of departing from the principles of civil liberty. These principles they carefully handed down to their sons, and in every period of the country’s progress they have been conspicuous. They broke out in full splendor in 1775 and ’76, of which the Declaration of Independence is an illustrious proof.—Again they shone forth with effulgent lustre in 1787 and ’88,–and the unparalleled Constitution of the United States was their fruit. These ancient, deep-rooted, republican principles of the country must be most sacredly regarded; for, be assured every variation from them will be resisted and bring on convulsions.

To have said thus much in favor of republican principles I hope will not be deemed to favor of party-spirit. For, I am designating the acknowledged principles of my country. And I beg leave to add, that they are principles of eternal rectitude and equity. Republicanism can no more be considered a party, than immutable truth and righteousness can be considered a party. And Republicans can no more be called a faction, than nature, reason and scripture with their Author, can be called a faction. For, these principles rest on the solid basis of nature, are clear as the sun to the eye of reason, and the Bible is full of them from beginning to end.—Nothing ever appeared to me more preposterous than to say the Bible favors of monarchy.—What did God say to his people, Israel, when they first asked for a king to rule over them? Read the eighth chapter of I Sam. And you will see how he resisted their request and set before them all the evils of monarchy. 1 But when the people were deaf, and said, (because they could say nothing better) Nay, but we WILL have a king,–then God gave them a king in his wrath. And wrath indeed it was!—If the public mind at any time become so depraved as that they will have a king,–why then there is no help for it; and it becomes the duty of good men to make the best of the evil. Thus did the prophets and good men in Israel.—But because they wished to make the best of an evil, shall it be argued that they were in favor of the evil and were its zealous abettors?

When Jesus Christ came, every maxim and every precept he gave, so far as an application can be made, was purely republican. If we had no other saying of this than this, it would be sufficient to determine the matter. Ye know, says he, that the princes of the nations exercise lordship over them, and their great ones exercise authority upon them. But it shall not be so among you:–but whosoever will be chiefest among you let him be servant of all.—True he did not come to inter-meddle with human governments. But it is plain to see what his real sentiments were. It was not without ground that he was suspected of not being very friendly to Cesar. If he paid him his tribute-money, it was on this principle, lest we should offend them. He was a friend to order,–but he was in favor of righteous order. Mind not high things, but condescend to men of low estate.

If there be a privileged order of men known in the Bible, it is the poor and the oppressed. Such are in Scripture taken to God’s peculiar favor, he appears their special protector and avenger, and denounces terrible woes upon the head of their oppressors.

Is not iniquity condemned in the Bible? But what is iniquity? The word is from in and aequus,–unequal:–not unequal as to property or any other accidental circumstance, or appendage; but unequal as to rights. Thus the thief claims a right to trample on the rights of his neighbor, with respect to property,–the slanderer with respect to character,–the murderer with respect to life. These will not be subject to laws which subject the rest of community; but must claim privileges above them and peculiar to themselves.—The noble lord, who trespasses with impunity upon the enclosures of his neighbors, differs nothing from the thief, except that the iniquitous laws of unequal government protect the one and hang the other.—Iniquity surely is hateful to God. He repeatedly appeals to mankind in his word, Are not my ways equal? Are not your ways unequal?

Thus republican principles are no party-principles, inasmuch as they are founded in nature, reason and the word of God. At any rate, they are the principles of our country; and in exhorting you to abide by them, I am sure I speak the mind of the country, and what she herself would urge with pathetic importunity, were she to rise in my place and address you.

Permit me further to say, you would not mistake the old and genuine maxims of the country, if you should set an inestimable value upon that instrument, called The Declaration of American Independence. There her principles are displayed. There they are graven as in adamant, never to be effaced. That was the banner she unfurled when she arose to assert her rights. Under that banner she marched to victory and glory. On that were inscribed the insignia of all she contended for.

Cherish then, that immortal document of what once were DECLARED in the face of the world to be the principles of this country. I firmly believe they are still its principles.

Give me leave to say further, you will not mistake the will and pleasure of the country, if you give all your friendship, all your best wishes, and all the support in your power to the incomparable Constitution of the United States. This Constitution was adopted by a fair expression of the public will. It is the government of the country and the ordinance of God. When we examine its merits, we find it but another edition of the genuine principles of republicanism,–equal rights its foundation, and the welfare of the people its object. The precious maxims of the Declaration of Independence are transplanted into the Constitution. And as under the former the country marched to victory, so under the latter she may advance to prosperity.

Let the Constitution then, be esteemed the Palladium of all that we hold dear. Let it be venerated as the sanctuary of our liberties and all our best interests. Let it be kept as the ark of God. Obey the laws of government. Be genuine friends of order. Take that reproach from the mouths of monarchs, that Republicans are prone to rebellion. Dissipate that stigma, if it has been fastened upon any of you, that you are Disorganizers, Jacobins, Monsters. Let your love of order consist not in profession, but in reality. Let it be manifested, like true religion, in practice. Love not in word neither in tongue, but in deed and in truth.

Be not devoted to men. Let principles ever guide your attachments. To be blindly devoted to names and man’s person’s, is at once a token of a slavish spirit, and a sure way to throw the country into virulent parties. Be ready to sacrifice a Jefferson as freely as any man, should he become elated with power, exalt himself above the Constitution and depart from republican principles. Our Constitution contemplated independent freemen, men having a mind of their own, when it provided the right of suffrage. If we are to follow a man blindly wherever he leads, and if his coming once into office is to secure him there forever, whatever his conduct be,–in the name of common sense let so idle a thing as suffrage be expunged from our Constitution, and save the people the trouble of meeting so often for election. So long as a man in power behaves well and cleaves to your own principles, give him your support and your applause. But the instant he departs from the line prescribed for him by your social compact, peaceably resort to your right of suffrage, and hurl him from his eminence, be he who he may. In the mean time, always be in subjection to the powers that be.—By thus devoting yourselves to the principles of our excellent constitution and to the existing laws of government, you will be sure to do the pleasure of the country.

Let me say further, the pleasure of our country is to be free from foreign attachments. To be devoted to England or France or any one nation in preference to another, is unjust in itself, and a sure method to convulse the country with parties. We ought to wish well to all nations, desiring their deliverance from evil, and that they may enjoy their rights and happiness, without connecting ourselves intimately with the fortunes of any.—One principal purpose for which we should look at other nations is to learn from their miserable experience how to preserve our own liberties, how to secure our own happiness.

Lastly, to be genuinely and truly RELIGIOUS, would not be mistaking the ancient maxims of our nation. As I have endeavored in this discourse to hold up before you one of the chief and most peculiar features of the gospel, and have urged it by various considerations, I shall not now be lengthy. Give me leave to say, the genuine spirit of the gospel is the very perfection of man. Possessing that spirit, nation would no more rise against nation, nor kingdom against kingdom, the lion would lie down with the lamb, and there would be nothing to hurt or destroy throughout the earth; each one might sit under his vine and fig tree, having none to make him afraid. Genuine Christianity is a system of complete benevolence. Where it enters with its spirit and power, every relation is rendered kind, and every duty is cheerfully discharged. In no relation would its effects be more excellent than between ruler and people. Not that church and state should blended in the manner which has so much afflicted the world. Far from it. Christ’s kingdom, in such a sense, is not of this world. But it would be no matter how much the spirit of Christianity were blended with the spirit of rulers, or with the spirit of the ruled. The more the better. If the spirit of rulers were to be perfectly Christian, tyranny would never more be known. And if the spirit of the citizens were perfectly Christian, there would be little or no need of government.

This peaceful religion is the nominal religion of our country. How would she rejoice if it might be the real religion? Then indeed would she be glad and rejoice and blossom as the rose. She would blossom abundantly, and rejoice with joy and singing. The glory of Lebanon would be given her, the excellency of Carmel and Sharon. Imbibe, then, into your souls the spirit of this most excellent religion, and bring forth its fruits in your lives.

On the whole, my hearers, take the particulars we have mentioned, and blending them into one character, put that character on; and proceed with it in all its dignity and amiableness, along the course before you. Uniting the principles of liberty with order, and crowning the whole with genuine religion, be clear as the sun, fair as the moon, and terrible as an army with banners. Amaze once more the tyrants of the earth when they look toward this land:–let them see that men can be free without licentiousness,–orderly without needing the shackles of despotism,–religious without the impositions of bigotry. By assuming this character, be invulnerable to your foes;–baulk the hopes of the envious.

Let this character be invariably maintained. On no occasion and on no account let it sink into the low regions of party. Ah! Stoop not—stoop not to the extreme littleness—I was going to mention instances, but the dignity of the pulpit checks me.—Far,–far from such despicable things be your conduct.—Let the American character be borne aloft. Let it soar like the Eagle of heaven, its emblem, bearing the scroll of our liberties through fields of azure light, unclouded by the low-bred vapors of faction;–and let it not be degraded into a detestable owl of night, to dabble in the pools of intrigue and party and delight itself in the filthy operations of darkness.

Where are our Fathers? Where are our former men of dignity,–our Huntingtons, Shermans, Johnsons, Stiles’s, who in their day appeared like MEN, gave exaltation to our character, and never descended to a mean thing?—It appears to me, in every department we are dwindled, and more disposed to act like children than men.

Let the spirit of our Fathers come upon us.—Be men:–rise:–let another race of patriots appear:–bring forward another band of sages. Let America once more be the admiration of the world.

Think not that the dignity of a nation can be commuted. Think not that it can be transferred from its only genuine feat, the mind of its citizens, and be made to consist in anything else.

Ou lithoi, oude xula, oude

Technee tektoonoon ai poleis eisin:

All’ opou ot’ an oosin ANDRES,

Autous soozein eidotes,–

Entautha teiche kai poleis. ALCEUS.“What constitutes a State?

“Not high-raised battlements and lofty towers;

“Not Cities proud, nor spangled Courts.—

“No;–MEN;–high-minded MEN;

“Men, who their duties know;–

“But know their rights,–and knowing, dare maintain.”

Yes, the true and everlasting dignity of a State spurns all commutation. It never can be made to consist in ornamented stone and wood.—You must be MEN, high-minded MEN, else the national character will unavoidably sink, prop it how you may.—What was Greece, what was Rome, when their MEN disappeared, their high-minded MEN? Splendor, pomp, luxury indeed,–enough of it;–but no glory. And soon their pomp was brought down to the grave. What was Egypt after its people became a race of slaves?—did their pyramids prop the falling character of the nation?—O Americans! Be MEN:–let the glory of the nation rest in the dignity of MIND.—Be like the pillars which formerly stood under and bore up your honor. It was a goodly range of plain, hardy, independent, republican Sages.—These are your best props.—Put them under again.—Many indeed are fallen. And chiefly thee we lament, O Washington, who waft thyself half our glory! What a pillar waft THOU in the fabric of our Commonwealth?—When shall another such arise?—But we hope we have others somewhat resembling.—Let us all, my friends, endeavor to be such. The way is open before us; and we have the best of models.—Be great then, like Washington,–be inflexible like Adams,–be intelligent and good like Jefferson.

Give me leave on this occasion particularly to point you to Thomas Jefferson as a laudable example of that magnanimous and peaceable conduct which I have recommended to you in this discourse, and which is so peculiarly necessary to be put in practice at the present juncture.—That he has been abused, I suppose will be acknowledged on all hands.—But have you heard of his complaining? Have you heard him talk of vengeance and retaliation? Do his writings heretofore betray a little foul? Does his late letter to his friend in Berkley, does his answer to the committee of the house of Representatives, does his farewell address to the Senate2 breathe the meanness of a spirit bent on revenge? Placid on his mount he seems to have sat, as Washington on his, and beheld the storm of passion among his fellow-citizens with no other sensations than those of extreme pity and deep concern for his country. Like Washington he seems to have looked with an equal eye to the north and to the south to the east and to the west of the Union, and wished them all happiness. Should it come to pass, that he can be so little as to discriminate one half of his fellow-citizens from the other half, and withhold from them all confidence and all respect, brand them for enemies and traitors, deprive them of all offices and honors, and depress and afflict them all in his power,–give me leave to say, I shall be one to execrate his conduct most sincerely. What! Shall the country be thrown into convulsion and wretchedness, and the conduct which does it, not be abominated?

But at present we are persuaded of better things. At least, every thing which as yet has transpired from him is directly the reverse. And it is for this reason that I point you to him for an example of what ought to be the conduct of all in the present posture of affairs.—O my countrymen! Those who have any regard for the peace and honor of America!—if you have been reviled, revile not again;–if you have been persecuted, bless; if you have had all manner of evil spoken against you falsely, recompense to no man evil for evil. In a word, be not overcome of evil, but overcome evil with good. Come, and in this holy sanctuary of God bring all your grievances, all your resentments, and laying them upon the altar of sacrifice, consume and purge them all away. Turning to the golden altar of incense, inhale largely the sweet perfumes of patriotism, charity and every heavenly grace. Let your breasts henceforth glow with nothing but these peaceful, exalted sentiments.

Then shall your dear country rejoice over you as her genuine sons,–her tears shall be dried, her reproach shall be wiped away,–peace shall be restored to her afflicted bosom; you shall be blessed with your own reflections, and generations to come shall rise up and call you blessed. AMEN.

Endnotes

1 Note. Those who are able to read the original Hebrew will find in this passage, as generally through the old Testament, ideas which can hardly be communicated by a literal translation.

2 The inaugural speech of the President had not at this time arrived. Otherwise a reference to that might have been sufficient, without alluding to the communications here mentioned, which had been seen.

The author presumes he shall not differ from the candid part of his fellow-citizens, if he declares this inaugural speech to be a very excellent specimen of fine sentiment, found policy, and of that magnanimity and moderation which are inculcated in this discourse. And he is happy to observe a very striking resemblance between the writings of President Jefferson and the late illustrious Washington, which augurs well for our country.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!