Sermon preached by Alexander W. Buel in Detroit on December 22, 1846.

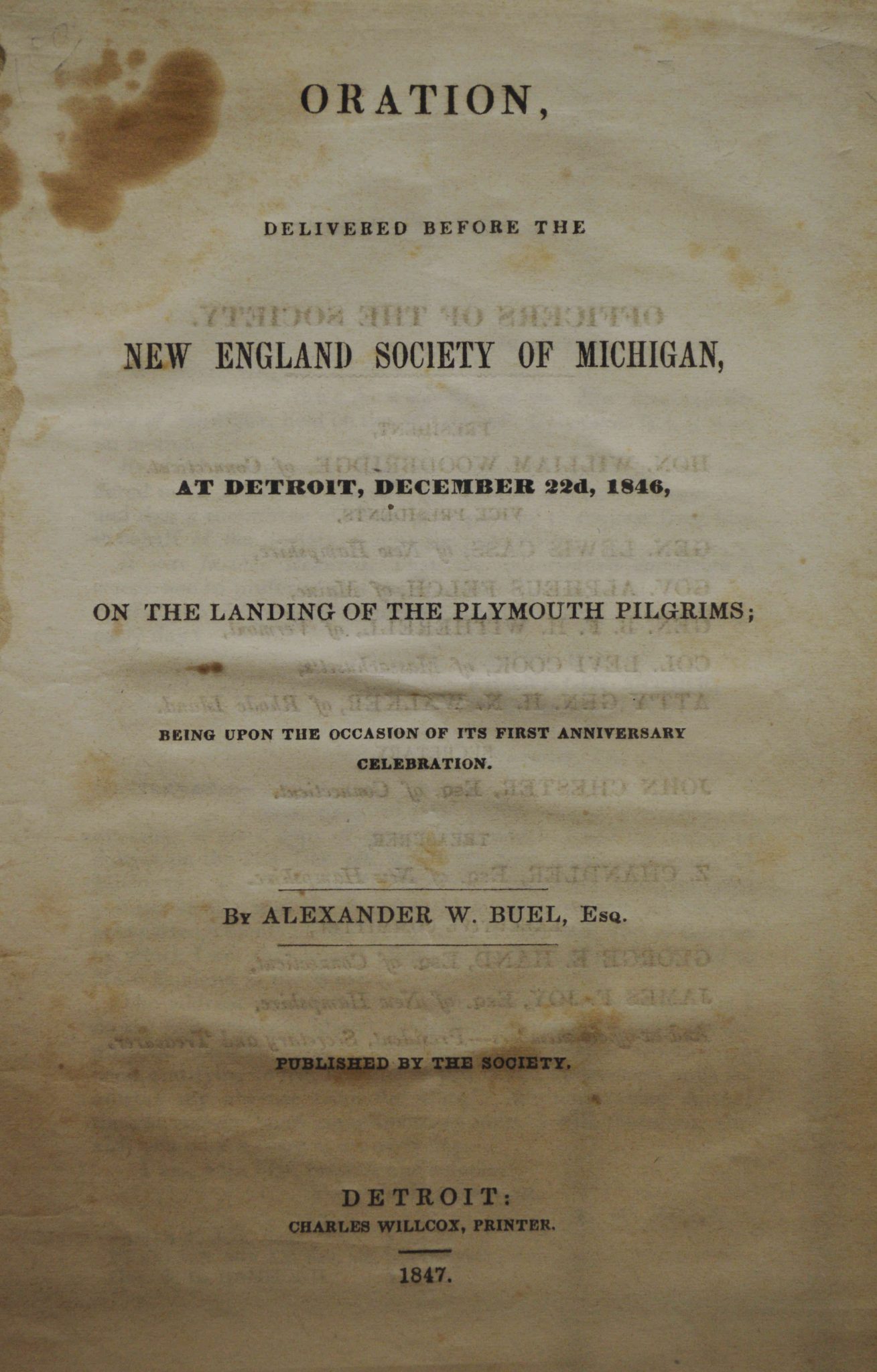

Delivered Before The

New England Society of Michigan,

At Detroit, December 22d, 1846,

On The Landing of the Plymouth Pilgrims;

Based Upon the Occasion of its First Anniversary Celebration.

By Alexander W. Buel, Esq.

OFFICERS OF THE SOCIETY.

PRESIDENT,

Hon. William Woodbridge, of Connecticut.

Vice Presidents,

Gen. Lewis Cass, of New Hampshire,

Gov. Alpheus Felch, of Maine,

Gen. B. F. H. Witherell, of Vermont,

Col. Levi Cook, of Massachusetts,

Att’y Gen. H. N. Walker, of Rhode Island.

Secretary,

John Chester, Esq., of Connecticut.

Treasurer,

Z. Chandler, Esq., of New Hampshire.

Executive Committee,

George E. Hand, Esq., of Connecticut,

James F. Joy, Esq., of New Hampshire,

And ex-officio members – President, Secretary, and Treasurer.

CORRESPONDENCE.

Detroit, Jan. 19, 1847.

A.W. Buel, Esq. –

Sir: At a meeting of the New England Society of Michigan, held on the 22d day of December last, it was on motion,

Resolved unanimously, That the thanks of the Society be tendered to A. W. Buel, Esquire, for his able and eloquent address, and that a committee of three be appointed to request from him in behalf on the Society, a copy for publication.

It was further Resolved, That the undersigned constitute a committee to prefer to you the request of the Society.

Will you oblige us by furnishing a copy of your address at an early day?

James F. Joy,

Franklin Moore,

C. G. Hammond.

Detroit, Jan. 20, 1847.

Gentlemen, –

I have received your polite note of yesterday, requesting of me a copy of the address which I had the honor to deliver on the 22d Dec. ult. Before the New England Society of Michigan. For the compliment it conveys to me, I beg to offer you personally, and the Society which you represent, my sincere acknowledgments of the obligations it imposes, and of the ties by which I am thus bound afresh to the land of my birth and to New England in the West.

The address was not written with a view to publication, but I do not feel wholly at liberty to decline furnishing a copy for the purpose desired. Opportunity for further review would have been gratifying to me, but this is prevented by business soon requiring my absence from the state. Without taking further time to answer your complimentary note, I will, therefore, furnish you with a copy at an early date.

I am, with high respect and esteem,

Your obedience servant,

A. W. Buel.

Committee:

James F. Joy, Esq.

Franklin Moore, Esq. and

Hon. C. G. Hammond

ORATION.

Sons of New England:

If the birth of a hero and statesman be a fit subject of popular rejoicing, much more is that of a distinguished race and nation. When one is born a savior of his country, the event itself received a nation’s honor; but he too forever shares with his fatherland the honors of her illustrious origin and destiny. This, a principle of interest, is the certain stimulus of national pride. The Athenian, who appeared in the streets of ancient Rome, felt himself honored as the polite and learned Greek; the Roman subject, as he visited the remotest countries of the world, carried with him the fame and power of the Imperial City; the American citizen, as he traverses every land and sea, feels himself invested with the power and insignia of popular freedom, and now the adventurous pioneer of the West is bold to exclaim, “I am a Son of New England.”

Whilst such sentiments spring congenial in the human breast, it is fitting, that we should meet to celebrate this day as the anniversary of an event, pregnant with the greatest revolution the world has witnessed since the days of Republican Rome. That event is the Pilgrim’s landing upon Plymouth Rock. Precious, memorable event! How plain and simple the story! The story of their persecutions, their wrongs, their sufferings, and search for a new home. The child may read it; and, as they wade one by one from their little ship, through the wintry waters of the ocean, so few are they, that even the child may number them and learn their very names. But this is New England; and where is the intellect that can contemplate her as she was, has been, is, and is to be, without a deep sense of national pride and patriotism? And where the American citizen, that will not permit her to share well in the honors of the republic, the glorious scenes of the past, the wonderful realities of the present, and the bright visions of the future?

No revolution can be measured in its birth. Time and distance give clearness and vastness to the view. The religious reformations of Germany and England are yet working out their natural consequences upon the destines of mankind, whilst the civil revolution of America is still exercising its infant powers upon the civilization of the globe. Thus, too, is with those great events, which prepare the way for revolution. Their greatness is realized in the distant future. In their day they may seem obscure and unworthy to be chronicled by the pen of the historian; but, when the law of cause and effect begins to develop its slow an resistless operations upon human civilization, simple events become revolutions. Hence genius can not be tried by its contemporaries, and no generation can best judge of its own virtues and vices. The landing of a few exiles, upon the shores of an unknown wilderness, seemed then to the world a small event in its progress and history; but now that event is clothed with the splendors of a revolution and a republic, whose influence upon the civilization of a world no human intellect can measure.

To us, through citizens of the West, New England loses not her interest. Today, from Plymouth Rock, she looks out proudly upon her child of the West, once more to behold many of her brightest jewels. Today she calls her children of the valley, whom she has sent forth as the embodiment of her spirit and genius, the emissaries of her civilization. Today she extends her maternal hand and claims us still. NEW ENGLAND HAS NO EXILES.

Obedient to the maternal call, we are now assembled under circumstances of more than ordinary interest. It is our first meeting beyond the waters of Erie, in an ancient city of a new state, whither more than a century since flowed one of the currents of European civilization, bearing upon its surface such bold pioneers as La Salle, Hennepin, La Hantan, Charlevoix, and Cartier; whilst their descendants have recently been overtaken by a different current, commencing in another direction, under the early guidance of such master-spirits as Winslow, Bradford, Brewster, and Standish.

It is not the least interesting circumstances of our meeting, that, although nearly a thousand miles distant, Pilgrim Hall at Plymouth does not today witness a more perfect representation of New-England from all her borders, that that which honors the present occasion. There Old Massachusetts well may dictate; here we will bow with veneration before her, as our most aged ancestor; but New England in the West knows no state ascendancy. Here is a full deputation direct from the Plymouth Pilgrims; but there is one, too, from the southern values of the Pequot’s, and one from the snow-white mountains of New Hampshire. There is one from the green hills of Vermont, and one from Sagadahoc and Pemaquid “on the Main,” far beyond the “strawberry banks” of the Piscataquis; whilst from Rhode Island and Providence Planation, the descendants of Roger Williams do equal honor to the occasion.

As we now approach more nearly the subject of this address – the emigration of the Plymouth Pilgrims – its causes and consequences – the difficulties and embarrassments of the speaker become more apparent. How can the human mind, in so short a compass, grapple with so mighty an event, involving as it does, revolutions within revolution? It covers a period of quite there hundred years, more pregnant than any other in the history of the world with weal or woe to the human race, commencing with the German Reformation, and terminating with that civil revolution, which gave birth to the American republic. It is a national event, and worthy of national honors. At first local and limited in its sphere of influence, it now assumes an importance, which its authors never contemplated; attaches itself to a train of results the most astonishing, and becomes identified with the interests of a new world.

Upon the occasion of our first anniversary celebration, I am therefore persuaded to attempt little more, than to present a general view of the subject, by rapid sketches and brief historical allusions. The origin and causes of that ocean pilgrimage are the topic, which first merits attention, and most abounds with lessons of instruction and wisdom. It is the true key to a solution of that wonderful event, that great historical enigma, a little band of self-exiles, without money, without property, without law, without charter, and midst trails and sufferings that cannot be described, forsaking for ever the endearments of friends and home, fleeing from the great chart of English liberty, encountering, in a fragile bark, the terrors of the ocean-storm, thrown by accident upon a frozen and unknown a coast, and wandering for days in search of some narrow spot, where they could enjoy undisturbed the sweets of new-born freedom. It is here that we must look for a development of some of those traits of character, which are entitled to the admiration of the world, and in which all mankind can find some standards of moral and heroic excellence.

He, who would comprehend the subject in its length and breadth, must commence with the world at the close of the dark ages, when the German reformers entered the arena to battle for popular rights. The great struggle which now began, and at times became so terrible with the fires of persecution, was a struggle for the rights of private judgment and free individual action in all matters of conscience and religion, the independence of the laity, and the supremacy of the civil power. It was a struggle for popular and democratic liberty, which speedily surpassed the early conceptions of the reformers themselves, and has finally worked out some of its legitimate results and triumphs in the republican freedom of the new world. The German monk emerged from his cloister in search of right, but he found a world in darkness. He returned, and again came forth, bringing a few Christian embers, whose occasional but brilliant flashes served only to increase the gloom. He returned again, and, in a remote corner, hitherto unexplored, with Christian torch in hand not all extinct, he spied and seized the Vestal fire of ancient lore, and fanned up both the feeble flickering’s, until they rose united in one consuming flame. Now again he came forth, holding for his armor, in his right hand the Bible, and in his left the ancient Greece and Rome.

The popular struggle now commences, based upon the most exciting elements, and involving new and extended claims in behalf of civil and religious liberty. It sought to revive both learning and religion,1 and soon spread with various success through several countries of Southern Europe. Although it perhaps no where completely triumphed, yet it at least resulted in a recovery of the supremacy of the civil power, a partial separation of church and state, and a dissolution of many of the bonds which made the peoples slaves to ignorance and superstition.

But the Reformation stopped not here. It crossed the British Channel, clad in similar armor; battling still for similar principles, and above all for freedom and independence of private judgment in matters of conscience and religion. It now became the English Reformation; and as it was attended by many peculiar circumstances of its own, and chiefly conducted by a new race of reformers, it is usually named with the honors of a distinct reformation. In England it found a genial soil, where the principles of civil liberty had held a firm root, and the native Briton was not prone to believe, that, under the boasted constitution of his country, he did not possess, though he might not enjoy, the right of private judgment and individual liberty.

One of the most remarkable circumstances attending the reformation is to be found in the singular struggle Henry the Eighth with the Court of Rome, in which the former triumphed, but without adding much to his character for moral consistency and integrity. The end of this struggle was in itself a revolution. Under a bull from the Pope, he married the widow of a deceased brother; became an author, and one of the Pope’s champions in opposition to Luther; was likened unto Solomon for his wisdom, and honored with the title of Defender of the Faith; in a few years desired from the Pope a decree of divorce, to ease his pretended scruples of conscience; and not obtaining it when he asked for it, he pronounced the marriage void; declared himself divorced, and lost no time in marrying he beautiful but ill-fated Anne Boleyn; thus claiming and exercising before his subjects and the world the private right of judgment, but upon an occasion not wholly unexceptionable as an example, although it raised up a mighty engine of the reformation in the person of the king himself.

Now upon one side followed the thunders of the Court of Rome. The King was threatened with excommunication unless he resumed his former connubial relations, and refusing so to do, was excommunicated. Under the other side, retaliation follows with rapid pace. The King secured the passage of an act cutting off all further appeals tot eh Court of Rome; resolves upon the abolition of the Pope’s power; secures the passage of an act in accordance with such resolve, and finally the Parliament (1534) solemnly enacted the King’s supremacy. Now, finding himself invested with the supreme power, the dissolution of the monasteries and confiscation of their property speedily follow; an unequal and terrible retribution this for refusing a decree of divorce. Thus did the early champion of Rome, her second Solomon, finally become a prince of English reformers.

The result of the quarrel was the recovery of the supremacy of the civil power; but strange to say, it brought with it partially the very evil it had overthrown. The act declaring he King’s supremacy, in the language of it, according to Bishop Burnet, proclaimed him “the Supreme Head in earth of the church of England,” and gave him power “to reform all heresies, errors and other abuses, which in the spiritual jurisdiction ought to be reformed.”2 Thus there was a mere turning of the tables. A religious dictatorship now existed in the person of the King. The arm of government was not to be used to perpetuate old abuses. The reformation was incomplete. It had worked a triumph of the civil power, but no separation of church and state.

Yet the great revolution of the mind in behalf of private judgment and popular liberty, still progressed. Reformers, noble and ignoble, multiplied in every direction; some for one reform, and some for another, but all for reform. Now commenced the great controversy about the ancient rites and ceremonies of the church, which seventy years afterwards led to the emigration of the Pilgrim Fathers. Some insisted upon their observance with ancient strictness; others thought the should be observed until abolished by the King’s authority; whilst others regarded them as “superstitious additions to the worship of God.” But this question lost its importance of a season, in the reign of Mary, when the supremacy of the civil power was again overthrown, and many of the great spirit of the age, such as Ridley, Latimer, Cranmer, Rodgers, Hooper, and Bradford, were consumed in the fires of persecution. The supremacy of the civil power, however, was again recovered on the accession of Elizabeth; but this led an immediate revival of old disputes amongst the reformers themselves, regarding the forms and ceremonies.

A new race of reformers now appeared, who aimed at a reformation of the reformed church itself, which they contended was corrupt with superstitious rites and forms. The struggle for further reformation grew fierce, and the result was the establishment of various independent sects in opposition to the English church, amongst which the Puritans were most conspicuous. Their opponents regarded this as Protestantism of a very obnoxious kind; Protestantism against the Reformation itself. The civil power, now the religious dictator, was therefore invite dot restore order, and quell all puritanical divisions. The result was the passage of the Uniformity Act, which empowered the Queen (in the language of Neal,) “with the advice of his Commissioner or Metropolitan, to ordain and publish such further ceremonies and rites as may be for the advancement of God’s glory;”3 thus making a religion for the soul, and appointing the Queen mistress of the ceremonies. A majority replied, ‘your chief doctrines we will follow, but to your ceremonies and practices we will not conform.’ The Queen answered, ‘we will compel you,’ and the answer was followed by subjecting them to hardships, sufferings and persecutions in a thousand forms. Ministers were deposed and left to wander as beggars. Whole congregations were turned out from their churches, and the great body of the Puritans were without the preaching of the Gospel, except the few how loitered about the doors and windows of their churches, and the great body of the Puritans were without the preaching of the Gospel, except the few who loitered about the doors and windows of the churches, and would enter only in season to hear the sermon. To this they replied, ‘we will assemble in private houses or elsewhere, that we may worship God according o the dictates of our own consciences. We will forsake your churches.’ This formed the great crisis which had never before been contemplated. This was SEPARATION. It amounted to a claim of sovereignty in the people, over mere rites and ceremonies. It was in fact a declaration of independence. The Reformation is now complete in the hearts of the Puritans.

But the thoroughness of the reform remain yet to be tested. To the resolve of separation, the Queen replied by putting in execution the penal laws for violations of the Uniformity Act. Ministers were still deprived of their pulpits. They were harassed by religious pies and forged letters, implicating them in some foul crime or conspiracy. The writ for the burning of heretics was revived. Their writings were suppressed. Their printing press was seized. They were obliged to hold their religious meetings in secret, often changing from place to place, to avoid discovery. The judgments of the star chamber were now invoked, and persecution waxed fierce in almost every imaginable form. The Puritans persisted in their refusal to attend church. The inexorable Queen replied, “we will compel you,” and reply was speedily followed by the Compulsory Act of 1592, entitled “An Act for the punishment of persons obstinately refusing to come to church, & c.” The penalty was imprisonment without bail; but if the offender became obstinate, and persisted in his offense, after conviction, he should ABJURE THE REALM, AND GO INTO PERPETUAL BANISHMENT; and, in case of failure to depart, or return without the Queen’s license, should SUFFER DEATH WITHOUT BENEFIT OF CLERGY!4

Thus did the government crown the pyramid of its persecution with this immortal act of tyranny. The Act of Supremacy, which pronounced the King Supreme Head in earth of the Church, had now worked out its final and legitimate result. The government could go no further, for by the act of 1592, it made the condition of the Puritans who returned from banishment without license, worse than that of the “felon upon the scaffold.” There was but one alternative left for them; voluntary exile, or submission of their consciences to the whims and caprices of an infatuated Queen, and in default thereof, imprisonment and death. What great delusion ever swayed and enlightened government? History is challenged to furnish a superior act of injustice and oppression. If we lift even the veil of the dark ages, we shall find with difficulty a parallel. It was, too, the act of Protestant England, who had so recently professed herself reformed and enlightened. If she were so, the more solemn and impressive is the voice of warning, which the spirit of popular liberty utters in behalf of a separation of church and state. With us, fortunately, their union find but few advocates, and Heaven grant, that this free republic shall never furnish an apologist for that memorable act of barbarity. Let him read it who will, and then say, if he can, that our Pilgrim Fathers had no cause of complaint. Is it a vagary of their imagination, that one should arm himself in the defense of freedom of conscience and religion? Is it fanatical, that one should be persuaded to flee from imprisonment, BANISHMENT and DEATH?

But, in defiance of the Compulsory Act, the genius of the Reformation still triumphed; popular liberty still struggled for civil and religious rights; the spirits of Wickliffe, Luther, Calvin, and Knox, of Rogers, Bradford, Hooper, and Udall, and the whole host of deceased reformers, appeared before them, and still pleaded for the rights of conscience, and a complete emancipation of the human mind, nerved their arms with strength divine, and fired their souls with the last desperate but sad resolve of forever forsaking a mother, who once had been so much loved, caressed, and venerated.

The second opens with new scenes, the most affecting and thrilling ever described by ancient or modern poet. The surges of the Reformation still swell upon the shores of England, whilst she is illumined to her center by the fires of persecution. Who is he, that now stealthily by night gathers his little flock in the streets of Boston, with their few earthy goods, about the conduct them to some foreign realm; thus daring to flee from his allegiance to the British Crown? ‘Tis John Robinson. But, alas! When safely aboard, they were betrayed by the master of the ship into the hands of their enemies; rifled, both male and female, of their money, books, and other property; exposed in the streets to the scoffs and jeers of the multitude, subjected to imprisonment without bail, and finally dispersed; seven of the ringleaders being still retained in prison. Amongst these were persons of no less distinction, then the venerable Elder William Brewster and William Bradford, the latter of whom was afterwards honored as the second Governor of New England.

They survived the storm, but not without losses and misfortunes. These rendered more apparent the necessity of success, and they resolved upon another effort at self-exile. A few months roll on. Look again; in a secluded spot, away upon the ocean’s shallow strand, remote from city, town, or faithless eye of man, and who is he, that thus strangely and cautiously flies upon the sandy beach, with sprightly vigor in his limbs, the fire of youth in his eye, and an anxiety of soul, that would give the world to obtain its desires, mingled with a joy of countenance, which naught cold enkindle, save a sure prospect of some great success? ‘Tis Robinsons again, gathering and ordering his little brand. A part is safely transported to the ship, now anchored far from shore, and all goes “merrily as a marriage bell,”

“as meekly kneeling on the shivering strand,

With fond ‘Farewell,’ they bleat their native land.”5

When lo! Oh heaven! Another cloud, charged with the lightning’s of persecution, lowers upon the joyful scene, and hurls its bolts of wrath at this happy Pilgrim flock. The enemy suddenly darts upon them, both horse and foot, armed with “bills, (axes,) guns and other weapons.” Swift the anchor is weighed, and the faithful ship now bears away upon the deep for safety, and in search of a new and distant home. But who shall depict the heartrending scene that now ensured, when so many innocent men, women and children, cast their longing eyes, some upon the receding ship, and some back upon the receding shore, and thus beheld in a moment wives torn from husbands and children from parents? Who shall depict the misery and destitution of those that remained? Their cries ascended unto Heaven; they were the cries of the widow and orphan.

Such are some of the labors, which precede the birth of a new state. Such are some of the trials and sufferings endured by our Pilgrim Fathers, in effecting their immigration o Holland in 607. In the ensuing year, the remained of the congregation, with their venerable pastor, emigrated, and me their brethren at Amsterdam. Here they remained but about a year, and in 1609, they removed to Leyden, a beautiful inland city, where they lived in the enjoyment of their religion and the worship of God, according to the dictates of their own consciences, until their final departure for the new world Although quite free and happy, yet their present taste of the sweets of liberty served to create an earnest longing for greater freedom, both civil and religious, the freedom of a new and independent state, which should be fashioned upon the basis of popular rights, and above all, popular freedom in religion. They finally concluded to remove to Virginia, and live in a distinct body by themselves, so soon as they could obtain a suitable grant or charter. This they could have obtained at once from the Virginia Company, but they were reluctant to accept any charter which did not carry with it the grant of freedom in religion. Hence, several years were consumed in efforts to obtain the religious franchise; so determined were they to preserve the absolute independence of their church. But at last they obtained nothing substantially useful. King James would promise nothing, save that he would connive at their religious meetings, and their patent from the Virginia Company was worthless, as it was taken in the name of one who did not accompany them, and it, of course, could avail nothing in effecting a settlement upon the coast of New England. These circumstances of apparent embarrassment were, without doubt, excellent good fortune. Had they obtained an available charter, it might have proved a link of servile dependence upon the mother country, and given a royal coloring to the early organization of the future state, which without it would be a pure democracy, a mere creature of the popular will It was this absence of royal charter and seal, which was to enable them to realize, upon the shores of the new world, the absolute right of popular sovereignty.

Thus, with no franchises, civil or religious, save those which the God of nature had given them; with no government, and with no organization whatever, save that of a mere religious assemble, which, by the laws of England, was a high offence; and even without a minister, for Robinson himself remained, they prepared for their embarkation at Delft Haven. In the history of the Pilgrim Fathers, there may, perhaps, be occasions which abound more with high-wrought scenes of passion, fear hope, suffering, and distress. Such an occasion was that, when these founders of a future republic, all safely aboard their little ship, in Boston harbor, and just read to catch with her sails the breezes which would waft them to a land of freedom, were suddenly delivered to their persecutors by a hireling traitor, imprisoned and dispersed, and all their hopes of freedom seem dot vanish forever. It was, too, a scene of suffering and distress, a scene of moral barbarity, when, having determined to make another effort to flee from their country, they selected a secluded post upon the short, and, being a surprised by an armed foe, amidst the joys and fears of a hidden embarkation almost complete, once more in vain they shrieked for freedom.

How unlike these was the scene at Delft Haven. Here were no hireling traitors, no armed persecutors. Here was no hope, save that of success; no distress, save that of separation; no sighs, except for friends and home; no tears, except those of parting. No storm lowered above; there was no fearful harrying to and fro. It was calm as the summer’s morn, and the stillness of mourning prevailed. It was a solemn occasion. It was the sublimity, not of terror, but of reason and the soul. Let us hear for once the words of one of the Pilgrims themselves, who thus describes it, in the simple and unaffected language of nature; “They went on board, and their friends with them; when truly doleful was the sight of that sad and mournful parting; to see what signs, and sobs, and prayers did sounds amongst them; wheat tears did gush from every eye, and pithy speeches pierced each other’s heart; that sundry of the Dutch strangers, who stood on the quay as spectators, could not refrain from tears. Yet comfortable and sweet was it to see such lively and sweet expressions of dear and unfeigned love. Bur the tide, that stays for no man, calling them away that were thus loath to depart; their reverend pastor falling down upon his knees, and they all with him, with watery cheeks, commended them with most fervent prayers, to the Lord and His blessing; and thus, with mutual embraces and many tears, they took their leaves of one another, which proved to be their last leave to many of them.”

The Speedwell, aided by a prosperous wind, soon bore the to Northampton, where there was a joyous meeting with their brethren on the Mayflower. Twice they put to sea, and twice returned to repair the pretended leakiness of the Speedwell, when they determined to dismiss her with such as were timorous and hesitating. They resumed their voyage in the Mayflower, and on the twenty-second day of November, (1620,) arrived in the harbor of Cape Cod, just one hundred souls, of whom forty-one were effective men. Here they landed, having first entered into a solemn compact, by which they promised submission to the laws of the future state, and John Carver was elected Governor. Hence an exploring party was sent out, which landed at Plymouth on the twenty-second day of December following, and selected it as a suitable place for a permanent settlement.

The Pilgrim wanderers are now content. They have at least found a resting place – a home. A free and unknown continent is their’s. They fear no union of church and state, for as yet NEITHER CHURCH NOR STATE EXISTS. Thus closes the second act of the drama.6

Another opens to present the grand denouncement of the scene.

Yes, Motherland! Unnumbered wonders past,

I’ve found thy dauntless pioneers at last.

O, could I paint the magic charms they traced

O’er all the features of the blackened waste;

The smiling homes and hosts that now appear,

Where savage sloth pined on from year to year;

The learned halls, the splendid temples piled

Where superstition cowered along the wild;

The flame-winged bark, whose harnessed thunder shakes,

From shore to centre these majestic lakes,

As on with iron thaw and painting glow

They waste the wealth of empires to and fro;

What pride, dear land, would swell thy matron breast?

What glad ‘Well done! Brave children of the West?’7

It is a fit subject for popular honors and rejoicings. The sober genius of prose is not satisfied, without borrowing from the imagination of the poet, and investing the theme with ideal forms. If the founders of Athens and Rome were honored for ages by public festivals and celebrations; if the Virgilian must might sing in immortal verse the wandering Trojans, who sought to establish a new kingdom in Italy, and the Lusitanian must sing upon the lyre of Camoens –

The heroes, an illustrious band

From Lusitania’s western stand,

Who, hon’ring oft the martial shrine

With warlike courage, strength divine,

Sailed far o’er seas ne’er tried before

By Taprobama’s spicy shore;8

Will any refuse to New England’s birth this day’s honors and festivities? And will not she yet bring forth some favorite son; some child of nature; some Milton,

who in angelic verse shall sing her Pilgrim band, that left their home

In distant lands as theirs to claim

A nation founded and its fame?9

The imagination may clothe and adorn New England in her infancy with her brightest pictures of the future, but the reality is no less. Although in the short space of three months, the Pilgrim family was reduced by sickness and death to fifty-six, of whom but twenty were effective men, yet fortune favored the hearts of the good and brave, who still lingered on England’s “guilty shore.” After the lapse of a year, it was still further reduced to just one half, when the Fortune arrives to swell their strength and numbers nearly to the original.10 The Anne and Little James follow.11

From the colony of New Plymouth springs the sister colony of Massachusetts Bay, which commences its early settlements at Salem and Boston, and both, increasing in wealth and population with every new arrival from England, now seem to be established beyond the reach of adverse fortune or hostile foe.

It may be amusing as well as interesting, to present in this connection a few of the first things of New England, gleaned chiefly from an early narrative of one of the Pilgrims.

Carver was the first Governor, and Standish the first Captain.

The compact, signed on the Mayflower in the harbor of Cape Code, was the first constitution.

Peregrine White, born at the same place and period, was New England’s first born. He was not insensible of his merits in this respect, since for this distinction he claimed and obtained a Grant of Honor, in the form of two hundred acres of light.

John Billington was the first offender, by having contemned the Captain’s orders, and was adjudged to have his neck and heels tied together. A bad man he, for he was afterwards hung for highway robbery and murder.

Ireland furnished the first minister, John Lyford.

Edward Winslow and Susanna White were the first bridegroom and bride; but, whether they were married after the technical manner of the common law, is at least doubtful, since at this time, (1621,) the colony had no minister, and being without legal grant or charter could have had no magistrates, except those made in town meeting. I will not, however, dispute the validity of the marriage, by opposing the law of nature with nice legal technicalities.

Two servants in the colony, Edward Doty and Edward Lesiter, the dual Edards, fought the first duel, for which they were adjudged to have their heads and feet tied together, and lie for twenty-four hours without meat and drink.

In February, (1622,) Standish appointed his first muster, or, I should rather say, general training.

The 18th day of December, (1620,) witnessed the first battle of new England, and this merits a particular notice, in connection with some observations upon the military organization of the Pilgrims.

No man, under the present circumstances, could have been better fitted for the head of the military department of the settlement, than Miles Standish. Napoleon, himself, would not have done half so well. He was bold, athletic, watchful, quick, prudent, sagacious, willing and ready to join with his men in the endurance of every hardship and suffering. He enjoyed the utmost confidence of his soldiers and the colony. When the voice of Standish was heard at the head of his little army, leading it forth to adventure or battle, there was a smile of content on every countenance, which seemed to speak “all is well.”

I think, too, withal, he was a little playful. When he signed the constitution on the Mayflower, he had not been elected military captain; but it seems he already enjoyed that tile, as he subscribed his name to that instrument, “Capt. Miles Standish,” the only title signature on the list, save a few bearing the humble prefix, “Mr.” This mode of subscribing one’s title is not very diplomatic or parliamentary, but I can readily pardon this slight breach of etiquette, when I image him the playful, as well as warlike hero of the company, and pressed into it by a general exclamation, “Now, Standish, ‘tis your turn. Sign, Captain and all.”

I cannot here refrain from paying some special attentions to what I denominate the first battle of New England with Standish at the head of her brave militia. “Attend, give ear, ye Gods!” whilst I rehearse such valorous deeds. As before mentioned, it was on the 18th day of December, (1620,) four days prior to the landing at Plymouth. Standish, not yet elected Captain, began thus early to display his military genius, and longed for a “brush” with the Indians. They had been sent out, ten all told, as an exploring party. It was midnight of the second day. Every man of the sentinels was at this post. They had heard of, but never yet heard the war-whoop of the savage, and it had inspired one of the more timorous with many direful imaginations. The forces were sleeping upon their arms, ready to do battle at a minute’s warning, when several hideous yells resounded through the camp, and aroused them from their troubled dreams. No sooner heard, than the cry “Indians! To arms! To Arms!” brought every man upon his feet, whilst random shot dealt out to the hidden foe destruction dire. But not much human blood was shed, for the wild foxes, being most frightened, were glad to find their holes.

This battle will ever justify the New England militia, in having been from time almost immemorial called “minute men.”

It is not to be supposed, that at this time military rules and tactics were closely studied or followed; yet the militia were then, as they ever since have been, the strong and popular arm of the public defense. A military organization of a popular character was indispensable to the general safety. By popular character, I mean that, which allowed no one to depend upon the colony for mere government protection, but made very able-bodied man a soldier, for the defense of himself and his fellows. Here is the true origin of our militia, and that popular spirit, which invests them with the idea that they possess some sovereign rights; that, as they are obliged to defend themselves against invasion, they have a right so to do, without waiting for the formal requisition of government.

At a somewhat late period on the colonial history, a dispute arose, which best illustrates the popular character and claims of the militia. The cross was one of the insignia upon the colonial flag; but it was regarded by the more popular party as a slight memento of the Uniformity Act, which had brought upon their ancestors so many troubles in their mother country. The contest grew warm, and it was comprised only by allowing it to remain in the flags of ships and forts, whilst the militia were excused from longer carrying it, as an emblem to remind them of former tyranny.

The subject now merits a sketch of the progress of enterprise and settlement in New England; but time and occasion will permit only a glance at a few of her early settlements, which soon sprang into powerful states and colonies. These found their origin in the spirit of immigration; an inclination to jingle in whatever was adventurous, dangerous, or marvelous, and in the efforts of feeble and remote settlements to promote their strength union and numbers, the better to enjoy the benefits of government and religion. The West may be apt to believe, that emigration is a new thing; but it as old as the “blarney rock.” It was no less active in the days of the Pilgrims than now. By its aid, feeble settlements grew with magic life into colonies, colonies into states, and states into a republic. That wave of civilization, which first proceeded from the Mayflower, has swept westward from the Atlantic, till, having passed the confined of the continent, and mingled with the waters of another ocean, it now rolls fast upon the shores of Asia.

Colonial grants and charters were the means by which the powers of the body politic were wielded. Proceeding from a royal source, they were nevertheless of a popular character, which not infrequently gave rise to mutual suspicions and jealousies between the King and the people. Upon the one side they begat a spirit of popular liberty, which at times threatened to overawe the regal authority; and upon the other fears, which could be allayed only by annulling or usurping their powers. Hence at one time we find the King vacating the charter of Massachusetts, and assuming to himself the entire government of the colony, whilst the same proceedings in Connecticut is receive with tokens of popular disturbance, and her character was concealed from the minions of power in that “brave old oak,” which she now hails as an ancient landmark of freedom.

The colonies of New Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay furnished chiefly the pioneers in the early settlement of New England. As fruitful mothers, they sent forth their children to populate the mountain and valley. Under the guidance of Captain John Mason and Sir Ferdinando Gorges, at a very early day, (1623), New Hampshire, bearing the poetical names of Marianna and Laconia, began to assume a little of state sovereignty and state rights, on the southern banks of the Piscatequa, at Mason Hall, now Portsmouth; whilst, under the same patronage and about the same period, Maine with magic life reared herself away “down east’ at Monhegan, Agamenticus or Little York, Saco, Damariscotta, Sagadahock, Sheepscot, and Pemaquid.

Such being the progress of events, the virgin enterprise of New England now makes another effort at colonization, when under the guidance of such men as Winthrop, Winslow, Haynes, Hooker, Wolcott and Mason, the Connecticut or Hartford colony, consisting of settlements at Hartford, Windsor, and Weathersfield, sprang up in the valleys of the Mohegans along the banks of the Connecticut, (1635). At Quinnipiack or New Haven, another distinct colony of note and celebrity was established, chiefly under the fostering care of Eaton, Newman and Davenport, the latter of whom was not only celebrated for his piety and excellence of character, but honored as the preacher of the first sermon at New Haven, (1638), and the prime move rof the proceeding in the convention held at Quinnipiack in the great barn of Mr. Newman, to frame a constitution. Such was the origin of Revolutionary Connecticut. No state can claim a birth more thoroughly popular and democratic.

The liberty of the new world soon began to develop some strange, though perhaps natural results. Freedom in government and religion with some degenerated into licentiousness, or blindness and infatuation, and with others into obstinate radicalism. This was a disturbance, which the early colonists never anticipated, proceeding from a new set of reformers, who proposed to outstrip the Pilgrims themselves in their claims for popular liberty. The course pursued by the old colonies, to suppress these radicals and agitators, neither occasion nor inclination will prompt me to defend. Suffice it to say, that, not being permitted to remain within the old jurisdictions, they went chiefly South, with the celebrated Roger Williams for a pioneer, and there gave birth to a new state, by settlements at Moshassuck, Shawomet and Aquidneck, now Providence, Warwick and Rhode Island, (1635). Thus did Rhode Island have her origin in a new species of intolerance; but it was an honorable origin. She was the land of the exile. Like the colony of Plymouth, she was born in a sea of trouble, a child of small stature but noble heart; and; if she but adhere to the example of her fathers, she may esteem herself with the preciousness of the tried jewel.

One star, of a later appearance, yet remains to be placed in the New England galaxy. Vermont—she too was born in a sea of trouble. Rebellion and civil war presided over her infant destinies. The Empire State fought for a rebel province; she for the rights of a separate colony. For her success in so unequal a contest, is she indebted to such spirits as Ethan Allen and Seth Warner. Whilst the government of New York, by a solemn legislative enactment, made their patriotic attachment to home equivalent to felony and punishable by death; and the governor tendered protection to all repentant rebels save these and a few others, offering also a reward for them of fifty pounds a head; they hesitated not to respond to these proceedings, by declaring publicly with legal precision and technicality, “We will kill and destroy any person or persons whomsoever, that shall presume to be accessory, aiding or assisting in taking any of us.” Nor did they hesitate to assume the responsibilities of the Old Congress, when, at the commencement of the revolution, the taking of the Ticonderoga and Crown Point presented fine subjects for New England adventure.

Having thus traced New England to some of her early colonial formations, it remains to conclude with a few observations upon early New England character; and how to glance even at a subject, which so readily furnishes material for a volume, is the greatest difficulty of the task.

One of the most striking features of New England character is its prevailing unity and uniformity, though mingled with some slight shade of difference, having their origin in peculiarities of early settlement. The blood is everywhere the same. Wherever it finds congenial channels, in Maine or Rhode Island, or east or west of her dividing mountain chains, we behold like institutions; the same indomitable love for individual freedom and action; the same hatred of tyranny; the same attachment to home; the same New England perseverance , enterprise and obstinacy. He, who dwells, far south upon the Saugatuck, will lose no time in recognizing upon the banks of Passamaquoddy the same bold and adventurous spirit, the same wandering sons of a Pilgrim race. And he, who would learn the origin of this ubity, after studying well the colonial history, must, with the little child, climb the mountain side, in search of the New England common school.

Amongst the outward characteristics of this unity, none perhaps is more prominent, than the inborn attachment to home, which swells in the breast of every New Englander, and increases with separation in time or distance. That patriotism, which would arm him, when the sovereign limits and jurisdiction of the little town or village of his birth are invaded, would be no more active in defense of state or national boundary. His migratory character is but the result of an antagonist quality, a restless enterprise, which sallies out upon the resources of the world, but never spurns the auspices of home and paternal gods.

To the New Englander, have also ever been dear the rights of private judgment, liberty of individual action, and freedom from dictation and usurpation. His smallest jurisdiction has its sovereign rights. In truth, a century before the American Revolution, sovereignty was believed and claimed to be a popular right. Actuated by such a belief, after the usurpation of Sir Edmund Andross, and when Massachusetts recovered her colonial independence by the new charter of 1691, her first words were, “No aid, tax, tollage, assessment, custom, loan, benevolence or imposition whatsoever, shall be laid, assessed, imposed or levied, on any pretense whatever, but by the act and consent of the Governor, Council and Representatives of the people, assembled in general court.” New Hampshire from her granite oracles, thundered forth the same notions of sovereignty, and Vermont, at alater period, in her Convention of Independence, hesitated not to hurl defiance at domestic as well as foreign usurpation, by publishing as her first right, “that whenever protection is withheld, no allegiance is due, and can of right be demanded.” Such was the spirit of sovereignty which prevailed, not only in these, but in all the New England colonies. It belonged, not merely to the colonial governments, the bodies politic, but to the New Englander himself; to the individual man, who formed his own theory and notions of natural and sovereign right. Such proceedings and opinions, the mother country soon regarded as the extremes of freedom, to be put down by the extremes of tyranny; but the firm resolve for complete independence nerved them for revolution, and successfully conducted them through its scenes of terror and blood.

The unity and uniformity of character, which distinguish New England, should not however be confounded with mere exclusiveness or selfish pride. She has also an American unity of character, which recognizes in her descendants, whether born on the banks of the Hudson. Mohawk, Ohio, Mississippi or the great Lakes, her children worthy of their sires, and extends the hand of fellowship to the oppressed of every land, without distinction of religious sect, or birth or clime. She looks beyond her granite hills, and recognizes in the early settlements of New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and the south, other branches of an ancient stock, who, with similar attachment of freedom and freedom’s soil, have at last met as Pilgrims in the Great Valley, there to revive in one common bond the ties of ancestral brotherhood.

As a religious sect, our Pilgrim ancestors were zealous and fervent; ardent in their piety; sincere in their devotions; democratic in their religious organizations; republican in their doctrines; and; if they were intolerant in maintaining them, it was because they had been tortured in the mother country into this extreme, as the only means of self-defence. It was because they found themselves compelled to put on the armor of their enemies. They had crossed the ocean amid trials and perils to obtain freedom of religion, and, it being obtained, they were ill disciplined to endure further disturbance or molestation. They could not so soon burst in every joint the shackles of centuries. It has been well said, that their virtues were their own, and their errors belonged to the age in which they lived. Could it be expected, that the character of a generation should be miraculously changed throughout? Or will any say, that without such change, tyranny might be a virtue, and resistance to it not evince a spirit of independence? The temple of republican liberty is not so easy of erection. Freedom ne’er thus

As politicians, they were active, and often found obstinately standing out for independent colonial rights. Some of the colonies were involved in mutual disputes about boundaries, which, at times, became almost border wars. State rights and state sovereignty, were then, as now, a favorite theme of controversy. The spirit and haughty tone of some of these disputes may be well exemplified, in a short extract from the address of the governor of Maine to Massachusetts, opposing the efforts of the latter to extend her jurisdiction over the former. “Our rights are equally invaluable as yours. Though you may boast of being owned by the Commons in Parliament, and expect to dwell in safety under the covert of their wings; we also are under the same protective power. * * *To talk gravely of artists to settle your latitude, to run your lines and survey your limits in these parts, is preposterous. We ourselves know something of geography and cosmography.” This spirited New England Governor had little idea of being restrained by such imaginary things as latitude and longitude.

As soldiers, the Pilgrim Fathers were brave but not warlike; obstinate in defense or attack, but humane; firm, but conciliatory; few, but invincible. The militia, the great bulwark of safety, were ever ready, at a moment’s warning, to leave the plough-share and drop the pruning hook, to repel the incursions of a hostile foe.

As patriots, let the part their descendants bore in the wars of their mother country, bear witness, and let this testimony be sealed with the blood of the revolution.

As statesmen, they were keen-sighted, cautious, prudent, wise, true diplomatists. They were the originators of that wise policy of non-interference in the affairs of foreign nations, which has more than once saved the republic from war. They studiously avoided interfering in the civil commotions of England, which followed their emigration to the new world. They were placed in most embarrassing circumstances, when two of the regicide judges of Charles I fled to them for protection; yet whilst the authorities made satisfactory pretenses of exertion to effect their arrest, the people managed so adroitly as to keep them concealed while living, and even their graves were such objects of secrecy, that they are now known only to conjecture or tradition. Prompted by the same wisdom and prudence , at an early day, most of the colonies entered into a perpetual league, offensive and defensive; thus early furnishing a prototype of the Revolutionary Confederacy and of the future republic.

As men of learning, talent, and intelligence, they were by no means inferior; and, if more need be said, I would invoke the testimony of their descendants, the living and the dead.

“New England’s dead! At that electric word,

How thrills the heart with patriot rapture stirred,

As buried forms of intellectual might

Like Endor’s vision fill the muse’s sight.”12

Of them as fathers, let the characters of their children testify; and, not to make honorable mention of the Pilgrim mothers, would be an offence not easily to be pardoned. Upon them higher praise cannot be bestowed , than to say in a word, that of such men, they were worthy partners, and well did they bear their part in fashioning the early destinies of this great republic.

Such is New England—the word lingers—the imagination still chains me to the theme. I must again return to the little bark, once more to look upon that winter scene. Blessed, glorious view! ‘Tis the silence of creation in her dawn, unbroken save by the roar of ocean, the rustling wind, or the Pilgrim’s prayer. Divine, immortal sublimity! To describe it, ‘twere not enough to seize the lyre of Homer, Virgil, or Milton, the chisel of Phydias or Flaxman, the pencil of Apelles Fabius or West. Who would equal the task, give him a pen divine, and let him sweep the chords of a celestial lyre. I behold the spirit-form of the Reformation. An aged and giant mother, bearing aloft the sacred oracles of God and nature’s scroll of freedom, she steps upon the ice-bound coast; points her mighty child to a new home; then quickly flies to her suffering children of other climes—away and beyond, o’er many a mountain chain, as far as eye can reach, another “deep and dark blue ocean” rolls. ‘Tis New England in her birth and New England as she was to be. I see also in the view her dashing streams; her thousand little hills and dales, and her beautiful valleys; whilst her evergreen but snow-bearing mountains pierce the heavens, and, looking down upon earth, as if with the hand of Omnipotence hang out from the clouds their everlasting crags.

I see, too, a stout, athletic manly form, moving his magic wand o’er the shores of the Atlantic; peopling them with a new race, and adorning them with the fruits and flowers of civil and religious freedom. A few years roll on, whilst he struggles with his onward course, and now from the top of the Alleghanies he looks out upon the great Western Valley, with a comprehensive vision not satisfied, until it rests upon the distant mountains of the Pacific. A few years roll on, and see! Resting on his journey, he now sits and reposes on the sands of the Western ocean, breathing in the swift-coming future the fragrance of oriental climes. ‘Tis the New England pioneer; himself a Pilgrim son of a Pilgrim father.

APPENDIX.

NOTE 1, p. 16

Statute of Queen Elizabeth, entitled “An act for the punishment of persons obstinately refusing to come to church, and persuading others to impugn the Queen’s authority in ecclesiastical causes.”

It is here enacted, “That if any person above the age of sixteen, shall obstinately refuse to repair to some church, chapel or usual place of common prayer, to hear divine device, for the space of one month, without lawful cause; or shall at any time, forty days after the end of this session, by printing, writing, or express words, go about to persuade any of her majesty’s subjects to deny, withstand or impugn her Majesty’s power or authority in causes ecclesiastical; or shall dissuade them from coming to church, to hear divine service, or receive the communion according as the law directs; or shall be present at any unlawful assembly, conventicle, or meeting, under color or pretense of any exercises of religion, that every person so offending, and lawfully convicted, shall be committed to prison without bail, till they shall conform and yield themselves to come to church, and sign a declaration of their of their conformity. But in case the offenders against this statute, being lawfully convicted, shall not sign the declaration within three months, then they shall adjure the realm and go into perpetual banishment. And if they do not depart within the time limited by the quarter sessions or justices of the peace; or if they return at any time afterwards without the Queen’s license, they shall suffer death without benefit of clergy.” 1 Neal’ History of the Puritan’s, pp. 283,284.

NOTE 2, p.21

The following is a list of the names of those who came over in the Mayflower, and as their names were subscribed to the constitution adopted on the vessel in the harbor of Cape Cod, before they landed.

- Mr. John Carver, + 8

- John Alden, 1

- William Bradford, + 2

- Mr. Samuel Fuller 2

- Mr. Edward Winslow + 5

- *Mr. Christopher Martin+ 4

- Mr. William Brewster + 6

- *Mr. William Mullins, + 5

- Mr. Isaac Allerton, + 6

- *Mr. William White, + 5

- Capt. Miles Standish, + 2

- Mr. Richard Warren, + 1

- John Howland,

- *John Goodman, 1

- Mr. Stephen Hopkins, + 8

- *Degory Priest 1

- *Edward Tilly, + 4

- *Thomas Williams, 1

- *John Tilly, + 3

- Gilbert Winslow, 1

- Francis Cook, 2

- *Edmund Margoson, 1

- *Thomas Rogers, 2

- Peter Brown, 1

- *Thomas Tinker, + 3

- *Richard Britterige, 1

- *John Ridgdale, + 2

- George Soule,

- *Edward Fuller, + 3

- *Richard Clarke, 1

- *John Turner, 3 Richard Gardiner, 1

- Francis Eaton, + 3

- *John Allerton, 1

- James Chilton, + 3

- * Thomas English,

- *John Crackston, 2

- Edward Dotey,

- John Billington, + 4

- Edward Leister,

- Moses Fletcher, 1 101

The figures denote the numbers in each family. Those with an asterisk (*) prefixed to their names, 21 in number, died before the end of March. Those with an obelisk (+) affixed, 18, brought their wives with them. Three, Samuel Fuller, Richard Warren, and Francis Cook, left their wives for the present either in Holland or England. Some left behind them part, and others all their children, who afterwards came over. John Howland was of Carver’s family, George Soule of Edward Winslow’s, and Dotey and Leister, and probably some others, joined them in England. John Allerton and English were seamen. The list includes the child that was born at sea, and the servant who died; the latter ought not to have been counted. The number living at the signing of the compact was therefore only 100. Prince’s Annals of New England, 173. Young’s Pilgrim Chronicles, 122. Hazard’s Collection, 101.

NOTE 3, p. 23

The exact bill of morality, as collected by Prince, is as follows:

In December, 6

In March, 13

In January, 8

___

In February, 17

Total, 44

Of these were subscribers to the Compact, 21

The wives of Bradford, Standish, Allerton, and Winslow, 4

Also, Edward Thompson, a servant of Mr. white, Jasper

Carver, a son of the governor, and Solomon Martin, son

of Christopher, 3

Other women, children and servants, whose names are

not known, 16

___

44

Before the arrival of the Fortune in Nov. six more died, including Carver and his wife, making the whole number of deaths 50, and leaving the total number of survivors 50. Of those not named among the survivors, being young men, women, children and servants, there were 31; amongst whom, as appears from the list of names in the division of the lands in 1623, were Joseph Rogers, probably a son of Thomas, Mary Chilton, probably a daughter of James, Henry Sampson and Humility Cooper. See Baylies’ Plymouth, 70; Belknap’s Am. Biog. Ii. 207; Morton’s Memorial, 376. Note in Young Pilgrim Chronicles, 198.

- John Adams

- Stephen Dean

- William Palmer

- William Bassite

- Philip De La Noye

- William Pitt

- William Beale

- Thomas Flavell

- Thomas Prence

- Edward Bompasse and son

- Moses Simonson

- Jonathan Brewster

- Widow Foord

- Hugh Statie

- Clement Brigges

- Robert Hicks

- James Steward

- John Cannon

- William Hilton

- William Tench

- William Coner

- Bennet Morgan

- John Winslow

- Robert Cushman

- Thomas Morton

- William Wright

- Thomas Cushman

Austin NicholasJonathan Brewster was a son of Elder Brewster; Thomas Cushman was a son of Robert; John Winslow was a brother of Edward. Thomas Prence (or Prince) was afterwards governor of the colony. De La Noye (or Delano) was, according to Winslow, in his Brief Narrative, “born of French parents,” and Simonson (or Simmons) was a “child of one that was in communion with the Dutch church at Leyden.” The widow Foord brought three children, William, Martha, and John. For a further account of some of these, and the other early settlers, see Farmer’s Genealogical Register, appended to his Hist. of Bridgewater, and Dean’s Family Sketches, in his Hist. of Scituate. Young Pilg. Chron. 235, note 2. See also Hazard’s Collection, 101-103.

- Anthony Annable

- Bridget Fuller

- Frances Palmer

- Edward Bangs

- Timothy Hatherly

- Christian Penn

- Robert Bartlett

- William Heard

- Mr. Perce’s two ser-

- Fear Brewster

- Margaret Hickes vants

- Patience Brewster and her children

- Joshua Pratt

- Mary Bucket

- William Hilton’s wife

- James Rand

- Edward Burcher and two children

- Robert Rattliffe

- Thomas Clarke

- Edward Holman

- Nicolas Snow

- Christopher Conant

- John Jenny

- Alice Southworth

- Cuthbert Cuthbertson

- Robert Long

- Frances Sprague

- Anthony Dix

- Experience Mitchell

- Barbara Standish

- John Faunce

- George Morton

- Thomas Tilden

- Manasseh Faunce

- Thomas Morton jr.

- Stephen Tracy

- Goodwife Flavell

- Ellen Newton

- Ralph Wallen

- Edmund Flood

- John Oldham

This list, as well as that of the passengers in the fortune, is obtained from the record of the allotment of lands in 1624, which may be found in Hazard’s State Papers, i:101-103, and in the Appendix to Morton’s Memorial, 377-380. In that list, however, Francis Cooke and Richard Warren’s names are repeated, although they came in the Mayflower; probably because their wives and children came in the Anne, and therefore an additional grant of land was made to them. Many others brought their families in this ship; and Bradford says that “some were the wives and children of such who came before.” Young Pilg. Chron. 351-352, note 3. Haz. Coll. 101-104.

Endnotes

1 Languages are the scabbard in which the sword of the spirit is found; they are the casket which holds the jewels; they are the vessels which contain the new wine; they are the baskets in which are kept the loaves and fishes, which are to feed the multitude. * * * From the hour we throw them aside Christianity may date tis decline. * * * But now that the languages are once more held in estimation, they diffuse such light that all mankind are astonished. Luther in 3d D’Aubigny, 189.

2 Burnet’s History of the Reformation, 218.

3 1 Neal’s History of the Puritans, 87.

4 For copy of said Act, see Appendix, Note 1.

5 Pitt Palmer. Poem read before the Alumni of the University of Michigan, 1846. Subject, New England. The author acknowledged his obligations to a friend, for the perusal of this interesting poem in manuscript. It is one of the high merit, and is about to be published by order of the society of Alumni. We bespeak for it a reception worthy of the New England Muse.

6 See Appendix, note 2.

7 Pitt Palmer.

8 As armas, e os Baroes assinalados,

Que da occidental praia Lusitana,

Por mares nunca de antes navegados,

Passram ainda alem de Taprobana;

Em perigos, e guerras esforcados

Mais do que promettia a forca humana,

Etnre gente remota edifacaram

Nova reino, que tanto sublimaram.

Lusiad, Cant. 1, Stanz. 1.

9 Ibid.

10 Appendix, Notes 3 and 4.

11 Appendix, Note 5.

12 Pitt Palmer

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!