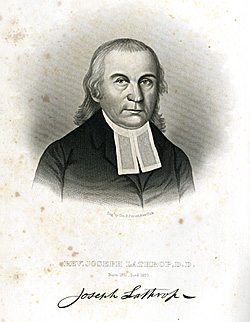

Joseph Lathrop  (1731-1820) Biography:

(1731-1820) Biography:

Lathrop was born in Norwich, Connecticut. After graduating from Yale, he took a teaching position at a grammar school in Springfield, Massachusetts, where he also began studying theology. Two years after leaving Yale, he was ordained as the pastor of the Congregational Church in West Springfield, Massachusetts. He remained there until his death in 1820, in the 65th year of his ministry. During his career, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity from both Yale and Harvard. He was even offered the Professorship of Divinity at Yale, but he declined the offer. Many of his sermons were published in a seven-volume set over the course of twenty-five years.

This Thanksgiving sermon was preached by Lathrop on February 19, 1795.

ILLUSTRATED IN A

SERMON,

DELIVERED AT

WEST-SPRINGFIELD,

ON THE NINETEENTH OF FEBRUARY, 1795.

BEING A DAY OF

GENERAL THANKSGIVING.

BY THE REV. JOSEPH LATHROP, D. D.

PSALM LXVII. 1, 2.

GOD BE MERCIFUL UNTO US AND BLESS US, AND CAUSE HIS FACE TO SHINE UPON US; THAT THY WAY MAY BE KNOWN ON EARTH, AND THY SAVING HEALTH AMONG ALL NATIONS.

It was after some happy change in the national state of the Jews, that this psalm was composed. The design of it was, to acknowledge God’s mercy in the deliverance granted them from late dangers and calamities, and to solicit the continuance of those gracious smiles under which they now rejoiced. A reason, why the Psalmist prayed for the prosperity of his own nation, was that God’s salvation might be known among all nations.

We will contemplate those circumstances, which are most essential to national prosperity and happiness: And then shew, that a regard to other nations should be a governing principle in our prayers for the happiness of our own.

I. We will, first, consider that national happiness, which is expressed by God’s blessing us, and causing his face to shine upon us.

When we speak of happiness in this world, we must understand it with its necessary qualifications.

There can be no complete happiness below the skies. The world does not admit of it, nor are mortals capable of enjoying it. Our natural weaknesses and passions as well as our vices and follies, render a state of society necessary to our tolerable subsistence; and, at the same time, render our happiness in this state very imperfect. There are evils which arise from the natural imperfection of society. To these we submit, that we may avoid the greater evils of solitude.

One half of the miseries of life result from our unreasonable expectations. We view the world in a false light, and demand from it better and greater things than it has to bestow. Hence, being deceived and mortified, we become discontented and envious. Let us bring down our views to the standard of nature, and, with these views, act well the part assigned us in life: Then will the world never deceive us; and never shall we feel the tortures of discontent in contemplating our own condition, or of envy in contemplating that of our neighbors.

The same moderate and rational views are necessary to the peace and happiness of a community. If men enter into society, with expectations of a state of public prosperity, which it is beyond the power of the world to give, or the capacity of mortals to receive, they will soon feel themselves disappointed; and, blind to the real cause, they will grow restless and impatient, imputing to the wickedness or misconduct of others the evils which naturally result from human imperfection, and which are artificially increased by their own delusive fancy. If we would enjoy the real benefits of society, we must consider it as consisting of men, like ourselves, weak, imperfect and mortal; and adjust our expectations to the nature and condition of things; mend where we can, and bare what cannot be altered.

1. The first thing necessary to national happiness is Freedom and Independence.

A people under the domination of a power out of themselves—of any power over which they have no check or control, are always liable to oppression, and never escape it long. No being, below the heavens, is worthy to be trusted with absolute, irresponsible authority. Such authority, in the hands of vain man, will soon be perverted to the misery of those unfortunate mortals over whom it is exercised. It is the interest of the tyrant to increase the burthen of his slaves, that he may enrich himself and his favorites; and it will be his policy to keep them low and uninformed, lest they should know their oppressions and seek redress. An attempt in government to obstruct the channels of public information, will always awaken the jealousy of a free and virtuous people.

2. That a people may be happy, their government must be good.

The ends of government are defense against foreign injury, and the prevention or redress of private wrongs.—That government only can be called good, which is adapted to accomplish these ends.—It must on the one hand, have so much energy, as to protect the individual in his personal rights, preserve internal tranquility, and collect the strength of all in the common defense: And it must, on the other hand, have so much liberality, as to reserve and secure to private citizens the full exercise of all that natural liberty which is consistent with those objects. A government framed and tempered in this manner, is calculated for general happiness.

The same boundary between the powers of government, and the liberties of the people cannot be fixed for all nations, nor for the same nation at all times. As a small and free people grow more numerous, wealthy, commercial and refined; their government will, of course, become more complex and will gradually assume a greater portion of the common liberties. To expect, in a state of civil refinement, all the freedom of native simplicity, is to combine, in imagination, things which are incompatible in nature. The savages of the wilderness have little property and less commerce. They are strangers to luxury and avarice, know but few wants, and feel but few temptations to injure one another. They live upon the chace, collect ornaments from the shells on the shore, stake their thirst at the stream, find a bed on the turf, and enjoy a shelter under the oak. Government with them is simple. Their natural liberty is liable to little restraint. They need but few laws to direct their conduct, and but few penalties to enforce their laws.

In civilized and refined nations the case is widely different. Separate interests awaken various passions, and urge to various pursuits. Industry and enterprise introduce wealth; this affords the means of luxury; and luxury creates new wants; these prompt to commerce, and to intercourse and connexion with different nations. Hence arises the necessity of numerous laws with penal sanctions to enforce them. Consequently men’s natural liberties are subjected to greater restraints for the more effectual security of their persons and properties. In this state of government there must exist a variety of offices. These raise expectation, and give play to ambition. Hence competitions among private citizens for places of power, and often bold strides toward despotism by those already in power.—Therefore that a people may be, and continue to be free, safe and happy, they must act well their parts in their private stations, and commit the administration of their public affairs to men, whose virtues and abilities entitle them to confidence. While they avoid a capricious jealousy, they must exercise a prudent vigilance, inspect the conduct of their servants, and transfer to better hands the trust which they find to be abused. They must disdain to become the dupes of party design and political intrigue; and spurn, with honest indignation, every attempt to corrupt their integrity and bias their freedom in the public elections.

3. A mild and prudent administration of government is necessary to national happiness.

The true object of legislation is, not the exclusive emolument of particular persons; but the general happiness of the community. Small inconveniencies had better remain, than the dignity of legislation be degraded for their removal. Frivolous laws bring government into contempt. Laws needlessly multiplied, and frequently changed, make duty uncertain and difficult to be known, and render government troublesome and hard to be obeyed. New laws create new obligations, generate new crimes, and increase the danger of punishment. Artificial crimes are easily committed, because conscience and habit have placed no guard against them. The frequent commission of such crimes facilitates the commission of real ones; and thus vitiates the public manners, and diminishes the energy and respectability of government.

Punishments are designed, not to take revenge for an offense, but to reclaim the offender and deter others from transgression. The efficacy of punishments to prevent crimes depends more on their certain execution, than on their extreme severity. The hope of impunity will usually be in some proportion to the severity of the punishment threatened: for this will interest humanity on the side of the offender, either to prevent a prosecution, or procure an acquittal. A moderate punishment is more certain in its execution; and it is certainty that carries terror.

Punishments, which, by stigmatizing or mutilating the body, consign the sufferer to perpetual infamy, should never be admitted. They are as contrary to true policy, as they are to humanity and religion. We should always aim to reclaim an offender: but if we would reclaim him, we must not make him desperate.

Whether capital punishments ought, in any case, to be inflicted on those, whom we have in our power, is a question, which, if the safety of the state will permit, humanity will choose to decide in the negative. To shorten the important term of human probation is, perhaps, too bold an assumption of God’s awful prerogative, except where he himself has expressly given the warrant. If a milder punishment is compatible with general security, it ought to be preferred. We look back, with horror, on some parts of the judicial system, which existed before the revolution; and we abominate the present sanguinary system in England. It is hoped that our experience will justify an increasing moderation.

There is, perhaps, nothing which so weakens government, as the severity, and so corrupts the manners, as the frequency of public punishments.

A people cannot be virtuous, while their conduct is embarrassed with numerous and uncertain laws, and their persons and properties endangered by a thousand wanton penalties.

4. Peace is an important circumstance in national felicity.

Internal Peace is the strength of a people, and their best security against foreign invasion. This is necessary to the improvement of arts, the culture of virtue, and the diffusion of knowledge, and the increase of national wealth.—A small people united are powerful and respectable. A great nation, divided into conflicting factions, soon become defenseless and contemptible. Divisions in government, and insurrections among the citizens, are ill boding symptoms. They indicate a distempered state of the body, and tend to dissolution.

Peace with neighboring nations is always to be desired. A people cannot be happy in a state of war. This is one of the greatest calamities incident to nations. It wastes their substance, consumes their youth, desolates their fields, corrupts their morals, and spreads distress wherever it marks its progress.

A wise people will study to avoid the occasions of war; they will be cautious, that they offer to their neighbors no real injuries, and that they resent not, in too high a tone, the injuries which they perceive. At the same time they will discover spirit to feel an unprovoked outrage, and firmness to support their national dignity.

No nation, perhaps, enjoys a situation more favorable to peace, than ours. We possess a fertile and extensive territory, productive of the various supplies of human want. Husbandry, and the arts subservient to it, are our principal object. The most useful manufactures are pursued to advantage. We have no distant colonies to defend; and no powerful enemy on our continent to fear. A wide ocean divides us from the proud and contentious nations of Europe. Our commerce, consisting chiefly in solid articles of human subsistence, is so important to most of those nations, that it will be an object of their attention. If we meet with injuries, too great to be borne, we may, without the danger attending hostile reprisals, probably obtain redress by a suspension of trade. This is always a just and inoffensive measure. It is the uncontroverted right of every independent people. No commercial regulation will be urged as a ground of war, unless a war was previously meditated, and a pretext insidiously fought.

5. Increasing population is among the circumstances of national prosperity.

The prophet, describing the happy state of the Jews, after their return from Babylon, says, “God will increase them with men, like a flock, and their waste cities shall be filled with flocks of men.” And, besides their natural increase, it was promised, that there should be large accessions from other nations, who, allured by the goodness of their land, the freedom of their government, and the excellency of their religion, should fondly seek a connexion with them. “Many people shall come and seek the Lord in Jerusalem, and from all languages shall men take hold of the skirts of him that is a Jew, saying, We will go with you, for we have heard, that God is with you.” 1

The happy increase of a people depends much on the healthfulness of their climate, the extent of their country, the fertility of their soil, their general industry, the facility of acquiring property, external peace, internal order, toleration in religion, a good civil constitution, and a wise administration of government. The singular concurrence of these circumstances strongly favors the population of our country.

A rapid increase, however, by the accession of foreigners, may be attended with some danger. It may introduce too great a diversity of interests, manners and habits, and may thus cause parties among the people, corruptions in government, and degeneracy of morals; and may eventually subject the country to a foreign influence. In prescribing the qualifications, on which foreigners shall be admitted to the privileges of natural citizens, the greatest care should be taken to guard against these evils.

6. General Plenty is an important circumstance in national happiness.

This is one of the blessings requested in this psalm—“Let the people praise thee, O God.—Then shall the earth yield her increase; and God, even our own God shall bless us.”

The wealth, which our Psalmist thought desirable, and which he considered as the fruit of God’s favor, was not the plunder and booty of war—not the ravages and spoils of conquest—not the influx of unbounded commerce—not the sudden accumulation of property in the hands of a few, effected by artful schemes of speculation, to the injury of many; but it was the rich produce of the earth, under the hands of honest industry, and the smiles of a bountiful sky.

Commerce is, indeed, useful, and in some degree necessary to civilized and refined nations. This brings many conveniences, which cannot otherwise be obtained. It contributes to the increase of knowledge and the improvement of arts. It humanizes the manners, gives spirit to industry, and a spring to enterprise. But when it becomes the principal object, it is dangerous to a people. Carried to excess, it supplants more necessary occupations. It raises some to opulence, but depresses the many. It introduces a disparity of condition inconsistent with general liberty. It tends to luxury and corruption of manners.

That kind of wealth, which arises from the culture of the earth, is the most valuable. This is immediately adapted to human use, affords necessary supplies for every member of society, prompts to general industry, yields the fewest temptations to vice, and is, in a competent degree, attainable by men of all conditions.

A people, who pursue their own happiness, will principally encourage this, the first employment of men, and those arts which are immediately connected with it. This gives them an independence of other nations, and brings others to a dependence on them. The Almighty promised to the Jews, that, when, for their obedience, he should bless them in their flocks and herds, in the fruit of their ground, and in all the work of their hands, then “they should lend to many nations, and should not borrow; should be above only, and not beneath.

7. Another privilege necessary to the felicity of a people is the gospel revelation; for this affords the means of religion; and on religion depends national, as well as personal, happiness.

We are not to expect the miraculous interpositions of heaven for individuals, or communities. God governs the world by such general and steady laws, as mark for all the several departments of their duty, and encourage their diligence in the parts respectively assigned them. There is an established connexion between virtue and happiness; and between vice and misery: and this connexion is as apparent in public bodies, as in private members.

The benevolent Ruler of the universe, delights in the happiness of his subjects. If he sends his judgments among them, it is in consequence of their iniquities, and in order to their amendment.

Without virtue, national liberty cannot be maintained. A corrupt and degenerate nation, by the force of an absolute tyranny, to which they have long been accustomed and under which their spirits are broken, may be held in a state of union. But a people possessing a free spirit, and enjoying a government of their own, cannot long continue in a state of internal peace and liberty, without a good degree of public virtue. In their case virtue must do that, which force does in the case of slaves.

All the social virtues are founded in piety to God; in a belief of his providence, a fear of is judgment, and confidence in his goodness and power.

RELIGION inspires men with love to one another, to their country, and to the world. It teaches them mutual justice, fidelity and condescention. It restrains them from oppression and fraud; curbs their ambition and avarice’ corrects their passions and sweetens their spirits. Influenced by religious principles, they will set those to be rulers over them, who are men of truth and integrity, fearing god, and hating covetousness; and rulers of this description, will be a terror to evil doers, and a praise to them who do well.

If piety and virtue generally prevail, a people will soon rise to dignity and importance; if they are extinguished, slavery and misery must ensue.

We are to consider the enjoyment of divine revelation, as our highest privilege. This, while it marks the way to eternal glory in the heavenly world, explains and inculcates the virtues, on which depend the happiness and safety of the nations on earth. It gives us exalted ideas of the Supreme Being, and enlarged conceptions of his government. It instructs us in the duties, which we owe to one another, and urges them by motives of the most solemn importance it has instituted those ordinances of social worship, which are wisely adapted to promote knowledge and virtue, to unite the members of society in sentiment and affection, to make every man useful in his station here, and prepare him for a higher and happier station hereafter.

The blessings, which have been enumerated, as necessary to national prosperity, are those which a gracious Providence has distinguished our happy lot.

We have a government of our own framing founded in principles of liberty – administered by men of our choice – and adapted to promote the happiness of all classes of citizens. Most other nations are under a government imposed by force, or palmed by artifice, continued by craft or power, and exercised with partiality and tyranny.

We are in a state of internal tranquility. This has, indeed, by the folly of some misguided citizens, suffered a momentary interruption, in an extreme part of the nation; but it is now happily restored. And doubtless, the well chosen terror, which soon compelled a submission, will be followed with a well timed lenity, which may conciliate lasting affection. If we look around, we see many nations in a state widely different from ours; either distracted with intestine divisions, or struggling for emancipation from slavery, or fainting in the arduous and unequal conflict, or suffering, or likely soon to suffer the convulsions of a general revolution.

We also – save that some savage tribes have molested our infant settlements, – now enjoy peace with all the nations of the world; while more than half of Europe are involved in the horrors of war, and are drawing forth their strength for mutual destruction. Our numbers, by internal population, and the accession of strangers, are rapidly increasing; while the nations of Europe are declining by the consumption of war, and the drain of continual emigrations.

Though, in the season past, the harvest in some parts suffered a sensible diminuition, yet we enjoy a competence of all the necessaries of life; and of many of them we have a surplus, from which we can, in a measure, answer the unusual foreign demand.

We are favored with the pure, uncorrupted revelation of the gospel, and with the free, uncontrolled exercise of religion; while a great part of our fellow men, are benighted in ignorance, blinded by superstition, or enslaved to a tyrannical hierarchy.

When we contemplate the difference between our own state, and that of other nations, our hearts should glow with gratitude to God who has made us to differ – should be filled with solicitude to ensure the continuance, by a wise improvement, of our privileges – should melt into comparison for the wretchedness of multitudes of our race – should be warmed with servant desires, that God, whose face has shone on us would cause his way to be known on earth, and his saving health among all nations.

This leads us,

II. To our second observation. That a regard to the happiness of other nations should be a strong motive to desire and pray for the happiness of our own.

Nations, however independent of each other, in the constitution of their own governments, are, in the divine establishment, nearly connected. Great and important events in one nation often extend their influence to many others. All history verifies this observation. Our own recollection confirms it.

The principles of liberty, which have been publicly defended in the writings of our country, and happily established in the revolution of our government, have passed the Atlantic, and called the attention of the nations in Europe. Some of them animated by our example, and emboldened by our success, have made spirited exertions to effect for themselves a change or reform. France has been hitherto successful; and her success will probably give the spirit and principles of liberty a more extensive spread. Much, however, may depend on our future wisdom and virtue. If we should disgrace our revolution, either by madly running into confusion on the one hand, or by supinely degenerating into despotism on the other, our example would damp the spirit, and obstruct the progress of liberty in the nations, which have begun to cherish it. But on the contrary, if we appear to be happy in the government, which we have adopted, many nations will partake with us in the felicity. Encouraged by our prosperity, they will amend their government in conformity to ours; and, in the mean time, the oppressed will find among us a safe retreat.

In order to our exhibiting such an example of national prosperity, as will attract the attention, and encourage the exertions of other nations we must preserve the true spirit of liberty, and the essential principles of our revolution. We must practice and promote the virtues on which the happiness of society depends; such as industry, frugality, justice and beneficence. As the foundation of all these, we must maintain piety to God, and support the means of piety which God has instituted.

“Righteousness exalts a nation.” Our national virtue considered only in regard to ourselves, will appear to be vastly important – as important as the liberty and happiness of increasing millions for an unknown succession of ages. But when we consider this virtue, as diffusing the same liberty, and the same happiness among other nations of the earth, its importance rises beyond the reach of imagination.

We are to love our country, and seek its peace. But true benevolence will not confine its regards to so small an object; it will extend its kind wishes and friendly embraces to the whole system of rational beings. We are to desire the happiness of our country, not merely for its own sake, but rather for the sake of mankind in general. We are to pray for God’s blessing and the smiles of his face upon us, not that we may have power to trample on the rights of others, but that others, by our means, may be free and happy. “God be merciful to us,” says the Psalmist, health among all nations. Let the people praise thee, O God. Let the nations be glad and sing for joy.”

While we rejoice in our national prosperity, let us not be high minded, but fear. Our situation is, in many respects, happy; but there are circumstances attending it, which may justly awaken apprehensions.

All governments tend to despotism. Without virtue and vigilance among ourselves, this will be the fate of our own.

While the war in Europe continues, our peace is precarious. Our commercial connexions with the belligerent powers, render our situation critical and delicate.

The war with the savages has been a national calamity; but most severely felt by those, who are immediately exposed to their incursions.

The conduct of the British government in detaining our posts contrary to the treaty of peace—in exciting the savages to make war upon us—in fending troops to aid them—in insulting our neutrality by capturing and condemning our vessels—and in compelling our seamen to serve on board their ships, is a full proof of their unfriendly disposition: And however the late Treaty may have issued, there is much ground to fear, that their professions will be delusive, and their friendship but temporary.

France, though hitherto remarkably successful, has not finished her conflict, nor established her government. Danger attends her still. The unhappy suppression of the revolution in Poland may, perhaps, give the Ruffians, who owe no good will to the French Republic, an opportunity to join the combination against her. The accession of so great a power to the general confederacy, will bring on France a great weight, which, after so long and violent exertions, may be too mighty for her alone to sustain. If she should ultimately fail in the conflict, we shall have cause to tremble for ourselves. To her successes, as the immediate cause, we are clearly to impute the continuance of our tranquility. That the British government have entertained hostile intentions toward us, there can be no doubt; and that their intentions have been diverted, rather by the French arms, than by any new and sudden impulse from their own justice and humanity, everyone must believe.

In the serious contemplation of our political state, not to mention our moral state, which surely is not the most promising, can we not discover much occasion to mingle prayers with our praises, and fear with our rejoicing?

The religion of the gospel influencing our hearts, and governing our lives, is our grand security. If this is treated with indifference, all our privileges are uncertain, and probably will be of short continuance; and the calamities, which distress other nations, will fall on us.

Let us then, in our respective places, contribute to the honor and influence of religion; obey it ourselves, and recommend it to others. Thus, while we secure our own souls, we shall, in the most effectual manner within our power, serve the interest of our families, our neighbors, and our country; and by promoting the interest of our country; we shall advance the general happiness of the human race.

Let us then adopt the prayer of the Psalmist;–“God be merciful to us and bless us, cause thy face to shine upon us; that thy way may be known on earth, and thy saving health among all nations. Let the people praise thee, O God; let all the people praise thee. Let the nations be glad and sing for joy; for thou shalt judge the people righteously, and govern the nations upon earth. Then shall the earth yield her increase; and God, even our God shall bless us. God shall bless us, and all the ends of the earth shall fear him.”

AMEN.

Endnotes

1. This passage, though literally descriptive of the State of the Jews, after their restoration to their own land; doubtless has a prophetic aspect on the state of the Christian church in some glorious period yet future.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!