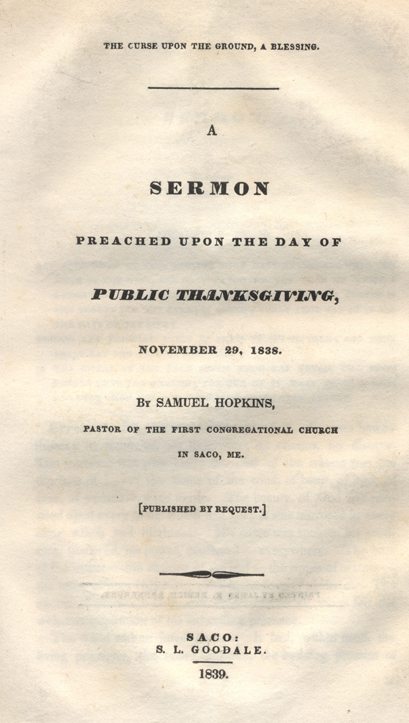

Samuel Hopkins (1807-1887) graduated from Dartmouth in 1827. He was a pastor of a church in Montpelier, VT (1831-1835), later in Saco, ME (1835-1842), and in Standish, ME (beginning in 1844). The following Thanksgiving sermon was preached by Hopkins on November 29, 1838.

A

SERMON

PREACHED UPON THE DAY OF

PUBLIC THANKSGIVING,

NOVEMBER 29, 1838.

BY SAMUEL HOPKINS,

PASTOR OF THE CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH

IN SACO, ME.

AND UNTO ADAM HE SAID, BECAUSE THOU HAST HEARKENED UNTO THE VOICE OF THY WIFE, AND HAST EATEN OF THE TREE OF WHICH I COMMANDED THEE, SAYING, THOU SHALT NOT EAT OF IT: CURSED IS THE GROUND FOR THY SAKE; IN SORROW SHALT THOU EAT OF IT ALL DAYS OF THY LIFE;

THORNS AND THISTLES SHALL IT BRING FORTH TO THEE; AND THOU SHALT EAT THE HERB OF THE FIELD;

IN THE SWEAT OF THY FACE SHALT THOU EAT BREAD, TILL THOU RETURN UNTO THE GROUND; FOR OUT OF IT WAST THOU TAKEN: FOR DUST THOU ARE, AND UNTO DUST SHALT THOU RETURN.

Before the fall the world was a paradise. Its roses had no thorns; its fountains, no bitterness; its charms, no disease. The sunbeam was pure life; the flow of the waters was like the flow of Love; the notes of the wind, of beast, of bird, of man, of woman – were music. The beauty of God was penciled upon everything which had life; it was mirrored in everything which had brightness. His name was spoken, his goodness, declared, his power, confessed – everywhere. The hum of the insect – the shaking of the leaf – the ripple of waters – the voice of man chimed together in the song of gladness. The chorus of praise to God was universal; for all things felt welcome inspiration of his indwelling presence.

The world was an infant heaven. It had, within itself, the living principles, the entire furniture, the budding promise of angelic bliss. All things here were such, that, had they gone on, untouched by the Spoiler, they would have developed, in the day of their maturity, as bright a display of the Godhead, as ripe and as rich a harvest of enjoyments, as heaven itself affords. Our first parents walked in Eden – as newborn spirits do in the upper courts of God-children in their conceptions, children in their enjoyments; reaching forth, and growing up, to the mark of spiritual manhood. But their infancy was without defect. Their happiness was pure and constant. Every bodily sense was a channel for some incoming enjoyment. Nature was their minister and their teacher. She brought them pleasures from throughout her storehouse. She showed them God in every pleasure;–in the moonlight, in the twilight, in the shade of their arbor, in the fruits they ate, in the waters they drank. They lay down and slept, they woke and arose, they communed and thought – with rejoicing and thanksgiving.

But the world is changed. The song of universal gladness has ceased. The bodily senses yield not only pleasure, but pain. The heat of the sun is not only genial but oppressive. And the earth itself, instead of ministering unmixed pleasure, teems with a thousand evils. Her soil – her products – are changed. She is under the curse of God. Now – it is ordained, that even the best of her productions should have somewhat of ill. Her beauties bloom to perish. Her flowers are armed with thorns and poisons. Her elements minister abounding discomfort. The whole system of nature has undergone means of subsistence. By the sweat of our face we must eat our bread, until we return unto the ground. This is the general condition of human life. Every man’s daily sustenance is the hard earning of toil and sorrow. Discomfort, and weariness, and pain, are the price of life. The few who are exempt from personal toil rely upon the toil of others.

This state of things was ordained when God uttered the words which I have chosen for my text. But for this decree, Nature would still have been as Nature was before the fall. We, like our first parents, should have been exempt from thorns and thistles and the sweat of the brow. To sustain life, we should have needed only to eat and to drink and to sleep. To partake of the bounties of nature we should have needed only to open the eye. But the decree was uttered. The ground was cursed. The result has been – want and toil, from generation to generation; a result which shall continue until the consummation of all things.

How many men have read the sacred record of this curse without understanding? How many have mourned and lamented over the change this curse has wrought. How few have discerned the loving-kindness of God herein, although that loving-kindness is woven with the very letter of the curse. Do chief magistrates call upon the people to thank God for ordaining that they must eat their bread in the sweat of the brow? Do devout men, when enumerating the mercies of the Lord, mention this? Do the children of poverty – do the hoarders of wealth – when they rise to their toils, or flee to their beds, think of this? And yet, here the blessing is – avowed in the very tenor and framework of the curse – taking effect from the very day of its utterance – only the second in the order of tie, only the second in point of value, concerning man – perpetuated, too, from generation to generation – and diffusing its precious influences throughout the world today!

But what! Is a curse a blessing! Is a curse reason for devout thanksgiving! Is not this a paradox—or rather an absurdity? I answer – neither absurdity – nor paradox. It is a simple and obvious truth that, next to our praises for Redemption by the blood of Christ, we owe God our praises for the curse recorded in the text.

That we may gain a clear view of this truth, let us examine – the reasons – and the influences – of this curse.

I. Its reasons.

Under the government of God, “the curse causeless shall not come.” He never dispenses an evil, great or small, spiritual or physical, temporary or eternal, without a reason; never, without a sufficient reason; never without a compelling reason. This is a fundamental doctrine; qualifying all the acts, the purposes, the laws, the words of God; a doctrine which he has abundantly revealed – which bears essentially upon his government, and character; upon our condition and duties.

There was a reason, then, for the curse we are considering. There is a reason for its entailment present day. God declares it. “Because thou hast eaten of the tree of which I commanded thee, saying , thou shalt not eat of it.” Disobedience of God was the grand reason of the curse originally; and our disobedience of God is the grand reason of its perpetuity. The curse was ordained because of Sin; it has continued because of Sin. It was established for a perpetual decree in full view, and because, of Sin which was, and Sin which was to be. It was established because – Sin being present – it was a curse necessary to the perfect adjustment of God’s purposes; necessary to the full play of his benevolence and grace; necessary to the grand experiment of human probation; necessary in a system of things where punitive justice was kept at bay; in short – necessary to the best good of man.

Sin, then, is its primitive reason; and the good of man, its secondary reason. It is a weight—thrown into the scale of contending influences—to keep God’s grace and man’s sin at equipoise; to give grace sway upon Sin; to keep Sin from defeating grace. Its origin was in the secret counsels of God’s benevolence; its nativity, a brilliant era in the history of God’s wisdom; its introduction to the world, a wondrous display of God’s loving-kindness.

A system of things which would do well for a holy being, would not do for a sinful being. A mode of life which would consist with the best good of the one, would not consist at all with that of the other. A Garden of Eden, with its spotless, changeless, universal beauties, and luxuriant abundance, would answer the purposes of man without sin; but if so – it would answer the purposes of man with sin – not at all. And the moment the character of man became changed by sin, there must needs be, to secure his good, a corresponding change in his mode of life. Hence the necessity of ordaining some change in nature; a change compelling man to sustain life at the cost of toil and weariness. This change was wrought in the curse we are considering. And surely00if there was benevolence in profusion and glory of Nature before the fall—there is benevolence in her comparative barrenness and noxiousness since. Thorns and thistles sprang up to elicit labor. Labor was ordained to abate, for the time, the plague of Sin.

To show you that I do not speak at random, I refer you again to the very edict by which the curse was established. You find there no malediction uttered—no bolt of damnation hurled—upon the transgressor. No curse is recorded there concerning mankind. The curse was upon the ground. And the curse upon the ground was, and was declared to be, a blessing upon man. “Cursed is the ground; “cursed, that it may “bring forth to thee thorns and thistles;” cursed, that thou mayest “eat bread in the sweat of thy face;” cursed “for thy sakes.”

But observe—

II. The influences of this curse.

See how it is a blessing to men. See—how it so9ls, essentially, the influence of Sin! See—how aptly it adjusts itself in the system of Grace! See—how it accords with the arrangements of Divine Mercy! See—how it has priceless value as a co-worker in the plan of Redemption!

1. Observe its obvious influence upon salvation. Many a saint is now in heaven whose first lesson in the school of Christ was learned through the chastening influence of the burdens of life. And many are the heirs of God here, who could tell you that unceasing toil first awakened the desire for heavenly rest -; that cares and burdens taught them to expect no quietude in this world; that this conviction led them to seek a better country; that thus, they first began a preparation for heaven by contending with inbred sin.

Men labor for the meat that perisheth. It perishes with the using. They get a good thing and it passes away. They crave again, and again they labor. They go from labor to labor—from care to care—from weariness to weariness. And if, per chance, they are so schooled by the bitterness of their travail as to confess the trouble and vanity of life—; if perchance, they come to cry out for brokenness of spirit—how fitly does the voice of Christ chime in with their necessities and their convictions—“come unto me—come unto me—All ye that labor and are heavy laden and I will give you—rest!” How like hope to the despairing—like the breath of heaven to the fainting—like the balm of life to the dying! And how many—first dispirited by the burdens of a weary life—have caught these words in faith, found rest to their souls, and blessed God for the bitter discipline of a hard and painful lot.

And is there no one, a joint heir with Christ, who could testify that his hope of heaven is quickened, and brightened, by the exhaustion of his worldly toil? Is there no one who could tell you, that he goes to the secret feast of his closet fellowship with a better appetite because of the burdens of life?—no one who could tell you, that they make him pant the more after God, and long the more for the crown of glory—the harp of perfect praise—the fruition of sinless rest? Is there no one who is nerved for his warfare, pushing upward toward the stature of perfection, sloughing off his deformities, and growing in very meetness for heaven, under the tuition of worldly toil—under the influence of this very curse of the earth? Are there none of Christ’s beloved who are thus getting meat out of the eater—and honey out of the rock? Yes—thousands.

But take another view. Suppose the garden of Eden were still blooming and bounteous as in the days of man’s integrity. Suppose the habitation of all men were beside its fountains—and beneath its fruitful branches. Suppose no toil were requisite to gain subsistence and comfort. How many—think ye—would have availed themselves of the offer of salvation? To how many—think ye—would the blood of Christ have proved a blessing? How many—think ye—would have sought, through that blood, an entrance into a better country, an heavenly? How many, under the influence of faith which is Life, would have fled to Christ for comfort? Were the world a good and easy home—were we fed and clothed and warmed and sheltered, without care or effort—were all our wants supplied as fully and as freely as our first parents’—who would set himself to the task of earning a better inheritance? Who would sigh for a better country?

Had the earth interposed no obstacles to our enjoyment—borne neither thorn nor thistle—imposed upon us no price of hard labor for her bounties—it is to be doubted whether the scheme of Redemption would not have passed away without a single trophy; whether the grace of God in salvation would not have been published without a single proof—; whether the verity of that grace would not have been an everlasting problem—; and the rising glory of that grace, remanded to everlasting night.

So far, then, as Sin is contrary to eternal life; and so far as universal luxury and ease would have been impediments to salvation—so far the sorrowful labor which God has apportioned to men fitteth, like a key-stone, into the stupendous arch of Redemption—holdeth us, like a spell, within the reach of Grace—and overshadoweth, like a Mercy-cloud, the whole span of our probation.

And, so far, the curse upon the ground was a priceless blessing upon man.

2. Observe the influence of this curse upon the remnant of human enjoyments.

A creature of perfect holiness would pluck with pure delight, and taste with a perfect relish, every bounty of God. He could walk in an earthly paradise and appreciate every circumstance of comfort. He could gather blessings—copious as the dews, and successive as the moments—without satiety. He would find a zest in every blessing—though all should cost him nothing.

But who does not know the influence of sin upon our relish of God’s blessings? Being sinners—that which costs us nothing we esteem lightly. The light of the sun costs us nothing—how little we rejoice in it. The air of heaven costs us nothing—with what thoughtlessness we breathe it. The outspread provisions of Grace cost us nothing—with what tameness we regard them. The great work of Redemption cost us nothing—how little we prize it. And so it would be of all the comforts which have survived the wreck and ruin of the fall—where they free as the light, the air, the grace of heaven, we should prize, we should enjoy them, as little. Food, and raiment, and warmth, and shelter, and home, — and whatever we relish now—would be insipid.

God has seen fit to throw in a corrective for this baneful influence of Sin. He has seen fit to establish an order of things which has redeemed human life from utter insipidity. He has seen fit to set a price upon our most essential blessings. He has seen fit that they should come to us by cost—by the sweat of the brow—by labor and toil and weariness. And—to secure the payment of this price—for man’s sake—to give relish and vitality to his blessings—he has uttered and confirmed the decree—”cursed be the ground.”

And now—the bounties of the world yield us enjoyment in true and undeviating proportion to the price at which we secure them. The rich man enjoys his abundance because of the toil and anxiety it has cost him. The man of hard bodily labor—enjoys his homely meal and his rough bed—because of the weariness which has earned them. The man of hard mental labor (for there is sweat of the brow in the study) enjoys his food and his bed because of the weariness and pains by which he has secured them. The parent enjoys his family circle, he comes home with gladness and appreciates the life and quiet of his fireside—be he poor, or be he rich—according to the toils and weariness of the day. A mother’s joy in the probity and promise of her child is proportioned to the care, the anxiety, the pains he has cost her. A Christian minister’s joy over the recovery of a backslider, or the dawning hope of a new born soul, is measured by the unseen solicitude, by the wearing and midnight labors, by the unpublished wrestling with God, through which he has won them.

All this relish of blessings, of whatever name, is linked in with, and evolved from, the toil and hardships by which they are preceded. It is the fruit of that wise economy which God established in the curse of the ground. It is the result of that connection, then fixed, between labor and the acquisition of good. The bearings of this connection are incalculable. It is operating all over the world. It is showering its benediction upon many a natural relation; upon many a bounty of nature; upon many a luxury of art. It is as the Wisdom of God brooding over chaos. It is as the enchantment of God circumventing and baffling the Spoiler. It is as the Life of God imbreathed upon the dying. It is as the Power of God—transmuting the stone to silver—bringing back again form and luster to the shattered tarnished diamond.

3. Observe the influence of this curse in the prevention of evils in the world.

Suppose, the world over, men were exempt from hard labor. Suppose sustenance and warmth came spontaneously. Suppose the eye was delighted and the body comforted with all that the lust of the flesh and the pride of life could crave. Suppose all men could live and have their heart’s content—without exertion. What would be the result? Who would venture to meet the result? “Pride, and fullness of bread and abundance of idleness,” partial as they were—were the damnation of Sodom. They would be, if entire, the utter damnation of the world. Were they universal, the world would be like Sodom; one vast theatre of abominations—one vast charnel-house of irrecoverable death. Depravity would have one unbroken holiday of reveling. It would sweep over the earth like a whirlwind. It would tear up the slender remnant of human enjoyments—like a tornado. It would stamp upon the relics of natural affection—upon the residue of inward hope and life—till they were ground to powder. It would wake up every passion to frenzy. Vice and crime, lust and cruelty—in then thousand shapes—would reign from morning till night, from night till morning. The smoke and the cry of torment would ascend without cessation. Every fountain of domestic enjoyment would be broken up; every note of love, silenced—as in the grave; every bond of sympathetic fellowship, severed; every feature of moral beauty and promise effaced separate interests would clash in strife and grate in discord. The knell of death would boom upon every gale—and the dirge of departed joys be screamed in every ear.

This is no visionary fancy. The restless faculties of the mind will have action. They will—they must have—pursuits. Withdraw from the sphere of their existence pursuits and employments which involve no sin—still they will have action; they will go out, under the guidance of domineering sin, to countless deeds of iniquity. And—in the practice of unchecked and undiverted sin—they must grow up to a giant strength; under the iron tyranny of accursing habits; erasing every form and every foot-print of enjoyment form off the face of the earth.

But look at the omens which imperfect experiment affords. The press of worldly toil is not distributed to men alike. The compulsion to labor differs in degree. Where, now, has depravity reached its tallest stature, and expanded to its most frightful strength? Where there has been “abundance of idleness.” Where the necessity for labor, as a means of subsistence—or as a means to meet artificial wants—has been abated. Where wealth has abated it. Where barbarism has abated it. The most vicious, the most wretched, the most loathsome, portions of the earth, at this very hour, are those where men are the least compelled to hard, and unremitting toil. The most vicious classes of our own community are those who discard patient, industrious labor. The pests of society—the tenants of our prisons—the victims of our gibbets—the inmates of our dens of infamy—are idlers; men and women and children who have been suffered to evade the restraining law of honest and productive industry. On the other hand the communities—the classes—among whom probity and happiness and virtue have most prevailed, are those who have been impelled, by natural or artificial wants, to the highest exertions.

And what do these facts import? Why! Plainly this; that labor and toil and the sweat of the brow are powerful checks upon human depravity. Plainly this; that if all demand for toil should cease, if all the wants of men were met without their exertion—the surges of misery and abomination would roll over the world in unbroken and cursed succession.

So then, toil – busy occupation – is the safety-valve through which the perilous excess of depravity is diverted. Men wish to evade it; and, if they might, they would. Hence the mercy of enweaving it, strong and stern as necessity could make it, with the very condition of human existence. Hence – as a universal law – it is the very secret of temporal salvation – the bridle upon the jaw of the devourer.

Behold, then, the deep wisdom—the careful kindness—the timely forecast of God, in the enactment of the decree—“Cursed is the ground for thy sake.” See here—a counterpoise against impetuous and deadly depravity. See here—a befitting provision for the emergencies of erring human life. But for this—what would our world have been? A Golgotha—an Aceldama—a muster-field of moral and bestial defilements—a very counterpart of Hell!

Look now, my hearers, at the curse of the ground. Behold how obviously it suits with the higher antidotes to Sin; how its harmonizes with, and helps on, the great work of salvation; how it is of vital importance to the efficacy of Redemption; how it vivifies the fountains of our earthly comforts; how it comes in as a temporary alterative to our depravity, putting check upon its growth, and woe; giving to our day of probation—and vantage ground to the means of grace. Look at all this—and say if men have reason to deplore the decree “that they should earn their bread by the sweat of the brow.” Say if they should curse the thorns and the thistles—the impediments to their enterprises—the taskmasters of their toil—which God has ordained.

I might point out the bearings of this doctrine upon several subjects of high practical interest; its bearings upon domestic education and parental duty; its bearings upon legislative policy and responsibility; its bearings upon the countless artificial luxuries of life, at which green-eyed sanctity is wont to point with abhorrence.

But I must stop. With one appeal I commend the truth to your consciences.—The sweat of the brow-the pressure of care and toil—are not among you calamities. They are not things to be thought of on fast days and forgotten on feast days. They are not things to be prayed against and denounced. They are blessings. You ought to bear them with cheerfulness. You ought to grapple with the thorns and thistles of life without murmuring. You ought to give God thanks for their multiplied profusion. You are getting many a choice treasure—you are culling many a delight—you are shielded from many a curse—by means of this curse upon the ground. Where would you be—what would you be—what would your world be, were this curse recalled? Could your suffrage avail, would you dare lift up your hand for its repeal? To repeal it would be death to all your joys; your hopes; your restraints; your probation. Nay—to recall it would baffle, irrecoverably, the brilliant schemes of God’s saving grace—it would consign you and me to abandoned depravity, and despair!

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!