Recently in the mainstream media the words “Nazi” and “Hitler” are perhaps two of the most commonly used words employed by pundits and even politicians. Those on the Left go so far as to claim that the current President parallels to Hitler,[i] with some public schools even teaching it in classrooms.[ii] Members of the Right retort that the rapidly growing socialist elements within the leftist parties are more deserving of the association because “Nazi” is simply an abbreviation of its full name—Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, or, National Socialist German Workers’ Party.[iii]

With the centrality of the debate and the frequency of its usage, it is no surprise then that the political arguments have led directly into historical debates about Nazism. Thus, the most recent development in this match of political badminton has materialized in a slew of articles from left-leaning authors denying any connection between the National Socialism of Germany during Hitler’s regime and the socialism on the rise today in the American Left.[iv]

The claim that National Socialists were not true Socialist is not entirely new, with Western Marxist and socialist economists and historians distancing themselves from Nazism by claiming that Hitler and his followers were actually capitalists.[v] The historical facts of the Nazi regime, however, leave little room for doubt, the National Socialist party truly was ideologically socialist in name and in deed.

In order to competently answer this question definitions for both socialism and capitalism must be adopted. The generally accepted fundamental distinction between a capitalistic and a socialistic economic system rests upon the ownership of the means of production. In free markets the private ownership of capital is safeguarded as an intrinsic right which the government is bound to protect. For example, in the American tradition considers protections for private property paramount, with Thomas Jefferson explaining that:

“A wise and frugal government, which shall restrain men from injuring one another, shall leave them otherwise free to regulate their own pursuits of industry and improvement, and shall not take from the mouth of labor the bread it has earned. This is the sum of good government.”[vi]

On the other hand, the general sentiments of socialist theorists suggest that the private ownership of the means of production leads only to the richer propertied classes oppressing the poorer non-propertied parts of the population. Thus, the hypothetical hallmark of a pure socialist society is one in which there is no real private ownership of the means of production, only public or state ownership.[vii] Simply put, socialism is the destruction of private property rights.

Although there are endless varieties when it comes to methods, ends, and styles of each capitalism and socialism, for the purposes of this investigation the basic understood definitions will provide a sufficient evaluative baseline. In short, the crux of whether or not the German National Socialists can be rightly considered as true socialists comes down to the status of private property during the Nazi regime. If the rights of private ownership were protected, then Nazism ought to be viewed as a form of capitalism. If, however, the Nazis dramatically infringed upon property rights to the extent that they failed to meaningfully exists, then their self-appointed moniker is rightly applied.

To discover how the Nazis approached the matter of private property Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf naturally reveals the early rational which would soon materialize once he gained power in 1933. The significance of Mein Kampf is seemingly often overlooked today with some writers drawing conclusions which even a quick perusal of the text directly refutes,[viii] but Hitler’s manifesto certainly captured much of what it meant to be a National Socialist. So much so, that the German Ministry of Culture later instructed that:

“Boys and girls in their teens must acquire a proper insight in order to understand this new Bible of the People. They must become acquainted and familiar with the lines of policy traced therein by the master’s hand. The grown-ups must, by reading this book, purify and strengthen their civic consciousness.”[ix]

Whatever the effect it had on German readers, one quickly learns two key facts concerning Hitler’s economic thought throughout Mein Kampf. First, that Hitler viewed Marxism as a Jewish scheme to destroy nations for their own capitalistic ends.[x] He explains that:

“I resumed the process of learning, and so came to realize for the first time what it was that the life work of the Jew Karl Marx was directed toward. Now I really began to comprehend his Capital, as well as the struggle of Social Democracy against the national economy.”[xi]

Hitler continued later in Mein Kampf to declare Marxism nothing more than “the pure essence of the Jew’s attempts” to achieve the “destructive purposes of the international world Jew.”[xii] For National Socialism to successfully come to power, Hitler believed that they must be extremely wary of being “eaten away by the poison of Marxism,” because the two ideologies, are on the face, so similar.[xiii] In fact, the future Führer

“What must fundamentally distinguish the populist world-concept [Nazi worldview] from the Marxist one is the fact that it recognizes not only the value of race, but the importance of the personality, and thus makes these the pillars of its whole structure…If the National Socialist movement were not to understand the fundamental significance of this basic realization, and instead were superficially to patch up the present State, or actually to regard the mass standpoint as its own [i.e. Democratic Socialism, which was a major party in Germany at the time], it would really be only a party competing with Marxism.”[xiv]

Thus, from Hitler’s perspective, Marxism differed from Nazism because the Nazis would not let the “international Jew” use them for capitalist ends, nor would they let any element of democracy remain. In fact, democratic elements were so repugnant to the National Socialist theory that the:

“State must release all leadership, but particularly the highest—that is the political—leadership, from its parliamentary principle of the majority (i.e. mass) rule.… Of course every man has counsellors to assist him, but one man makes the decision.”[xv]

This explains Nazism’s repression of Marxists throughout the regime—a fact sometimes offered as proof of National Socialism’s underlying capitalism. But Hitler and his followers rejected Marxism on the belief that it was a clandestine method for achieving capitalism, believing that the class warfare was merely a pretense, “meant solely to prepare the ground for the rule of truly international finance capital.”[xvi]

Thus, the problem with Marxism for the Nazis was its Jewish connections and Hitler’s belief in an undercover capitalism inherent in the methodology suggested for reaching socialism, not anything pertaining to economic socialism itself. Therefore, the professed goal of a Marxist revolution—that being socialism—was still a valid and desirable end, but the method for attainment would be that of German Nationalism.

In fact, Hitler routinely showed his frustration for those whose, “brains have not grasped the difference between Socialism and Marxism even yet.”[xvii] Significantly, the more astute and principled of German businessmen resisted Nazism on the grounds that it was a modification of Marxism sharing the same goal but substituting the class struggle with race.[xviii]

The second revelation about Hitler’s economic development is that after his interaction with soon-to-be Nazi economist Gottfried Feder, Hitler’s whole view towards capitalism and wider economics changed.[xix] Feder became one of the earliest members of the National Socialist party and his economic policy had enormous influence early on.

Hitler explains that even though he was, “attentive as I had always been to economic problems,” his knowledge was relegated to social experience with little theoretical development.[xx] But upon listening to Feder’s lectures, “the idea instantly flashed through my head that I had now found my way to one of the prime essentials of the foundation of a new party.”[xxi] These ideas led directly to the formal creation of the Nazi Party.

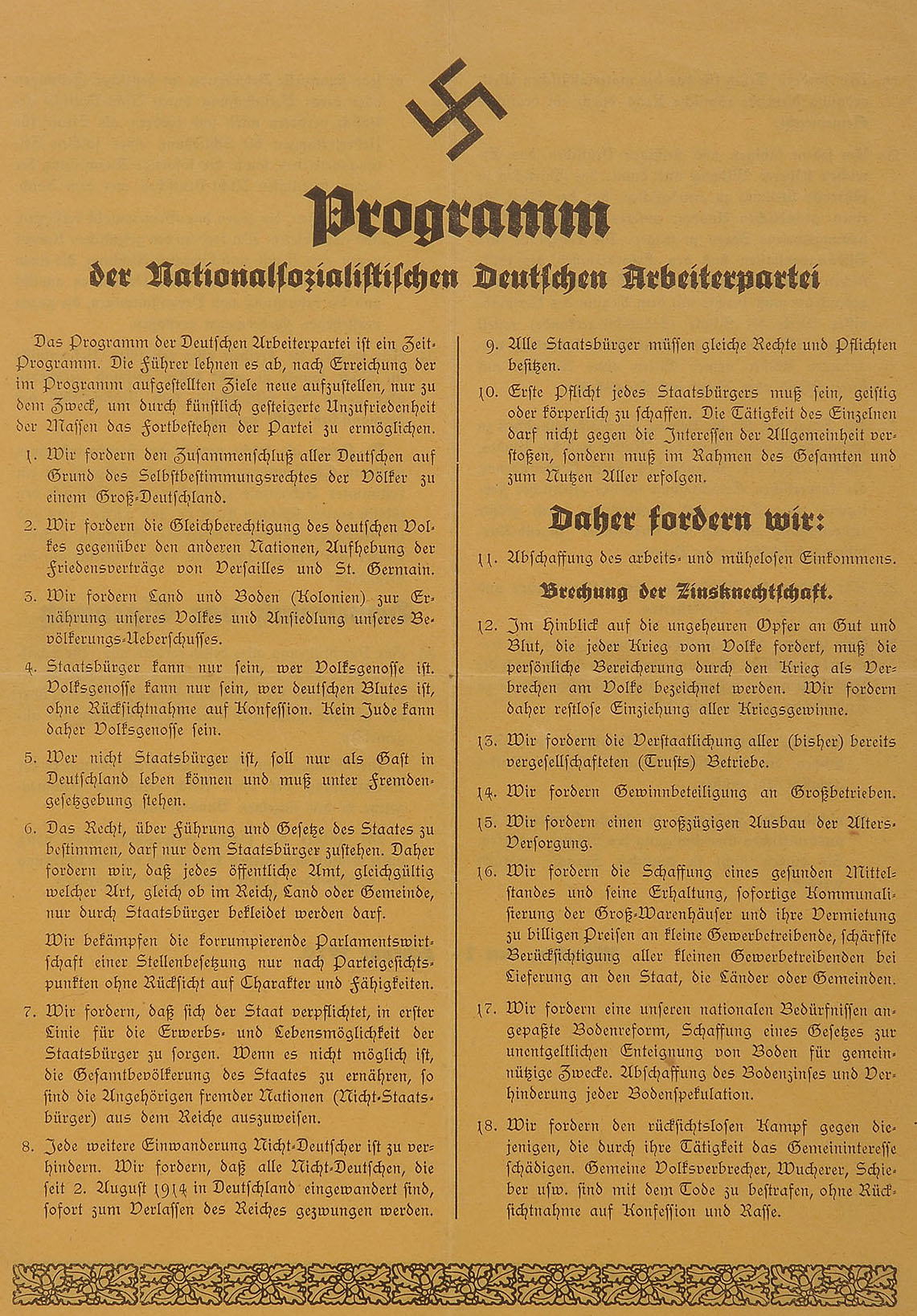

The influence of Feder on Hitler extended well beyond the pages of Mein Kamp. It is notably present when Hitler announced the Twenty-Five Points on February 24, 1920, which constituted the political

platform of the National Socialist party (at this point they were still the German Workers’ party, but changed the name later that year). Along with the typical and expected aspects of pre-war Nazism (such as abrogation of the Treaty of Versailles, the restoration of the colonies, and blatant anti-Semitism), there were many plainly socialist aspects reflecting Hitler’s growing commitment to the system.

Points 7 and 10 suggested increased government interference and control of the “industry and livelihood of citizens,” through ensuring everyone “work with his mind or with his body…for the general good.”[xxii] Point 11 demanded the “abolition of incomes unearned by work,” while point 13 called for the “nationalization of all businesses.”[xxiii] Many of the other articles within the platform—such as points 14, 15, 17, and 18—all advocated for distinct increases in government control of finances and close regulation of profits and property.

It was in the principles of the Twenty-Five Points that Hitler declared:

“The National-Socialist German Workers’ Party has a foundation which must be immovable. The task of our movement’s present and coming members must consist not in critically reworking these guiding principles, but in pledging themselves to them.”[xxiv]

But what happened once Hitler and his National Socialist party took power? His socialist intentions to regulate, direct, and nationalize the economic nature of Germany were plain, but upon taking the reins how did the Nazis manage their newfound Reich?

An invaluable source of information concerning the economy of the National Socialist Germany comes from those dissident voices who managed to escape the censors or flee before all contact to the outside world was cut off. One such voice was Emil Lederer, a Jewish professor of economics at the University of Berlin who fled to America after being deposed of his teaching position. In a 1937 article he explained a fundamental law of economic theory, writing that, “inasmuch as reality is never the crystallization of a pure principle, every historical system is more or less a compromise.”[xxv]

Thus, the Nazis were never able to perfect their Twenty-Five Points and create a pure socialist system—much like any other proclaimed socialist state, reality universally underperforms the ideal. In Hitler’s Germany, however, the central economic planners were able to get remarkably far in securing the government supremacy. Lederer concludes that, “this new economic system built up in Germany, taken in its structural character,” was designed so that the entire population was, “organized for purposes fixed by the government.”[xxvi]

Lederer is far from alone in his evaluation. Famous Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises, building off of his famous 1940 work on economics, declared shortly after the war that:

“The doctrines of Nazism are vicious, but they do not essentially disagree with the ideologies of socialism and nationalism as approved by other peoples’ public opinion. What characterized the Nazis was only the consistent application of these ideologies to the special conditions of Germany.”[xxvii]

Later in his writings Mises identifies Nazism as one of the “two patterns for the realization of socialism,” with the other being Russian Bolshevism.[xxviii] The key distinction between the German and Russian varieties, is that National Socialism, despite their intentions, “nominally and seemingly preserves private ownership of the means of production.”[xxix] At this point, some writers positively declare that Nazis were not real socialists and instead sought to preserve a capitalistic system, or at the least they failed to actively purge capitalism from their midst.[xxx]

However, although the term “private property” was preserved, it remained little more than an entry in the dictionaries. At any moment, if the Nazi leadership demanded it, anyone could be deprived of all their assets without warning or recourse. For example, we see the appropriation of the Junkers airplane factory in 1934 and the institution of Hermann Goring Works in 1937 designed specifically to, “encourage compliance with government production plans.”[xxxi]

Similarly, when even some of the most powerful manufacturers failed to meet government demands, “the state simply replaced his organization with one better suited to the National Socialist war effort.”[xxxii] In the end:

“the state therefore could direct the firms’ activities without acquiring direct ownership of enterprises.…They were opposed to capitalism and formal markets.”[xxxiii]

A different German businessman lamented to a confidant that the situation meant the destruction of private industry through a variety of means, saying that:

“You have no idea how far State control goes and how much power the Nazi representatives have over our work.…These Nazi radicals think of nothing except ‘distributing the wealth.’ Some businessmen have even started studying Marxist theories, so that they will have a better understanding of the present economic system.…You cannot imagine how taxation has increased. Yet everyone is afraid to complain about it. The new State loans are nothing but confiscation of private property.”[xxxiv]

In the end, Nazism left no room for private property. If the state has the power, ability, and inclination to confiscate the means of production whenever their wishes are not conformed to there is no real private ownership anymore. A common anecdote within the cowering business class remarked that:

“Under National Socialism you are allowed to keep the cows; but the State takes all the milk, and you have the expense and labor of feeding them.”[xxxv]

This nominalization was even outlined by Nazi economist Othmar Spann who desired a state where private ownership existed only in a, “formal sense, while in fact there will be only public ownership.”[xxxvi]

The effects of the National Socialist system of central planning, government control, and arbitrary powers destroyed whatever vestiges of private financial vivacity remained, with the purposes of making it all the easier for the State to consolidate its grip on every aspect of production. Quality of goods rapidly fell while prices remained steady, and out of what little raw materials which were available most was rapaciously consumed by the military. Thus, as early as, “1936 almost complete control over production could be exerted.”[xxxvii]

The effects of the National Socialist system of central planning, government control, and arbitrary powers destroyed whatever vestiges of private financial vivacity remained, with the purposes of making it all the easier for the State to consolidate its grip on every aspect of production. Quality of goods rapidly fell while prices remained steady, and out of what little raw materials which were available most was rapaciously consumed by the military. Thus, as early as, “1936 almost complete control over production could be exerted.”[xxxvii]

Even in military matters, the Nazi system was ill-equipped, and despite outspending England nearly two-to-one in 1940, Germany still produced 50% fewer planes and 100% fewer vehicles.[xxxviii] Additionally, factory laborers often were required to work up to 70 hours per week without a corresponding rise in wages.[xxxix]

Therefore, National Socialism rightfully earns its designation because it generally achieved, or significantly worked toward, the hallmarks of a socialist system. The objection on the grounds of private property has been proven to be merely a mirage, with the arbitrary State being the ultimate decision maker and real owner of the means of production.

To a large extent, perhaps unparalleled anywhere besides the Soviet Union, Hitler realized his vision of autocratic socialism. Thereby confirming his 1925 threat that, “the future lord of the highway is National Socialism,”[xl] which exists solely because, “it has the life of a people to destine and to regulate anew.”[xli] Nazism is clearly inseparable from socialism and ought to be recognized as such.

Endnotes

[i] Gavriel D. Rosenfeld, “An American Führer? Nazi Analogies and the Struggle to Explain Donald Trump,” Central European History Volume 52, Issue 4 (December 2019): 554-587.

[ii] Aris Folley, “Maryland Republicans criticize high school lesson comparing Trump to Nazis, communists,” The Hill (February 23, 2020), https://thehill.com/homenews/state-watch/484284-maryland-republicans-criticize-high-school-lesson-comparing-trump-to (accessed March 28, 2020).

[iii] Dinesh D’Souza, The Big Lie: Exposing the Nazi Roots of the American Left (Washington: Regnery, 2017).

[iv] Josh Bresnahan, “Bizarre fight breaks out in House over whether socialists are Nazis,” Politico (March 26, 2019): https://www.politico.com/story/2019/03/26/congress-socialist-nazi-debate-1237472 (accessed March 28, 2020); Jane Coaston, “Adolf Hitler was not a Socialist,” Vox (March 27, 2019): https://www.vox.com/2019/3/27/18283879/nazism-socialism-hitler-gop-brooks-gohmert (accessed March 28, 2020); Ronald Granieri, “The Right Needs to Stop Falsely Claiming that the Nazis were Socialists,” The Washington Post (February 5, 2020), https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/02/05/right-needs-stop-falsely-claiming-that-nazis-were-socialists/ (accessed March 26, 2020); David Emory, “Were the Nazis Socialists?” Snopes (accessed March 28, 2020): https://www.snopes.com/news/2017/09/05/were-nazis-socialists/.

[v] Cf. Maxine Sweezy, The Structure of the Nazi Economy (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1941); Richard Evans, The Coming of the Third Reich (New York: Penguin Group, 2003), 173; Ian Kershaw, Hitler: A Biography (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2010), 269-270.

[vi] Thomas Jefferson, “Inaugural Address, March 4, 1801,” The Works of Thomas Jefferson (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1905), 9.197.

[vii] Cf., Ludwig von Mises, Human Action: A Treatise on Economics (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1996), 4.998.

[viii] For a clear example of this see, Kershaw, Hitler, 269-270.

[ix] Quoted in the preface to, Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (New York: Stackpole Sons Publishers, 1939), 5.

[x] Hitler, Mein Kampf, 194, 212, 305-307, 433, 469, 525.

[xi] Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (New York: Stackpole Sons Publishers, 1939), 212.

[xii] Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (New York: Stackpole Sons Publishers, 1939), 433.

[xiii] Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (New York: Stackpole Sons Publishers, 1939), 435.

[xiv] Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (New York: Stackpole Sons Publishers, 1939), 434-435.

[xv] Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (New York: Stackpole Sons Publishers, 1939), 435.

[xvi] Hitler, Mein Kampf, 212.

[xvii] Hitler, Mein Kampf, 469.

[xviii] Matt Bera, Lobbying Hitler: Industrial Associations between Democracy and Dictatorship (New York: Berghahn Books, 2016), 222.

[xix] Hitler, Mein Kampf, 206-208, 212.

[xx] Hitler, Mein Kampf, 206.

[xxi] Hitler, Mein Kampf, 208.

[xxii] Anson Babinbach and Sander L. Gilman, “The Program of the German Workers’ Party: The Twenty-Five Points,” The Third Reich Sourcebook (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), 13.

[xxiii] Babinbach, “The Program of the German Workers’ Party,” 13.

[xxiv] Hitler, Mein Kampf, 446.

[xxv] Emil Lederer, “The Economic Doctrine of National Socialism,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 191 (1937): 221.

[xxvi] Lederer, “The Economic Doctrine of National Socialism,” 225.

[xxvii] Mises, Human, 1.187.

[xxviii] Mises, Human, 3.717.

[xxix] Mises, Human, 3.717-718.

[xxx] Cf. Kershaw, Hitler, 269-270; Granieri, “The Right Needs to Stop Falsely Claiming that the Nazis were Socialists”; Gunter Reimann, The Vampire Economy: Doing Business Under Fascism (New York: Vanguard Press, 1939), 314; John D. Heyl, “Hitler’s Economic Thought: A Reappraisal,” Central European History 6, no. 1 (1973): 92.

[xxxi] Peter Temin, “Soviet and Nazi Economic Planning in the 1930s,” The Economic History Review, New Series, 44, no. 4 (1991): 576-577.

[xxxii] Bera, Lobbying Hitler, 224.

[xxxiii] Temin, “Soviet and Nazi Economic Planning,” 583, 588.

[xxxiv] Reimann, The Vampire Economy, 6-7.

[xxxv] Reimann, The Vampire Economy, 309.

[xxxvi] Quoted in Mises, Human Action, 2.683.

[xxxvii] Arthur Van Riel and Arthur Schram, “Weimar Economic Decline, Nazi Economic Recovery, and the Stabilization of Political Dictatorship,” The Journal of Economic History 53, no. 1 (1993): 97-98.

[xxxviii] R. J. Overy, “Hitler’s War and the German Economy: A Reinterpretation,” The Economic History Review, 35, no. 2 (1982): 286.

[xxxix] C., “Will Hitler Save Democracy?” Foreign Affairs 17, no. 3 (1939): 461

[xl] Hitler, Mein Kampf, 525.

[xli] Hitler, Mein Kampf, 559.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!