|

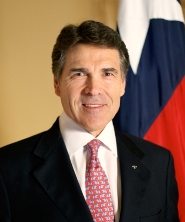

In 2011, over 32,000 from across the nation gathered at Reliant Stadium in Houston at the request of Texas Governor Rick Perry for a day of fasting, repentance, and prayer for America. Protestors ringed the outside of the event, which is a potent commentary on the condition of the culture today that so many object to Americans voluntary gathering for prayer.

Media coverage prior to the event was largely negative, with many articles happily providing critics a free platform from which to spew their hate. Particularly preposterous were the historical arguments leveled against the event.

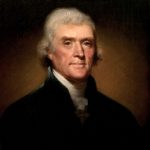

For example, in the Houston Chronicle, so-called “First Amendment scholar” David Furlow claimed that “the Founding Fathers wouldn’t have been fans of Gov. Rick Perry’s official involvement with a Christian day of prayer.” 1 To prove his point, he asserted:

Thomas Jefferson famously coined the phrase ‘wall of separation between Church & State’ when describing the First Amendment to Baptists who asked if the president would dare ‘govern the Kingdom of Christ’.

First, Jefferson did not coin the phrase. It was introduced in the 1500s by leading clergy in England who objected to the government taking control over religious doctrines and punishing religious activities and expressions. In America, many famous early ministers also used the phrase – all well over a century before Jefferson did.

First, Jefferson did not coin the phrase. It was introduced in the 1500s by leading clergy in England who objected to the government taking control over religious doctrines and punishing religious activities and expressions. In America, many famous early ministers also used the phrase – all well over a century before Jefferson did.

Second, nowhere in the letter from the Baptists to Jefferson or in his reply to them2 was it ever questioned whether “the president would dare ‘govern the Kingdom of Christ’.” To the contrary, the Danbury Baptists, Jefferson’s ardent supporters during the presidential election, consoled him by telling him that the vicious attacks against him by his political enemies in New England had been because he had properly and vigorously refused to “assume the prerogatives of Jehovah and make laws to govern the kingdom of Christ.” Jefferson’s reply letter simply reassured the Baptists that the government would definitely not prohibit, inhibit, limit, or regulate religious expressions – exactly the opposite of what Furlow claimed.

Third, on multiple occasions, Jefferson called his state to Christian prayer and worship. In 1774, he called for a day of fasting and prayer, 3 which included that all the legislators “proceed with the Speaker and the Mace to the Church” to hear prayers and a sermon. 4 He also urged his home community around Charlottesville to arrange a special day of fasting, prayer, and worship. 5

Third, on multiple occasions, Jefferson called his state to Christian prayer and worship. In 1774, he called for a day of fasting and prayer, 3 which included that all the legislators “proceed with the Speaker and the Mace to the Church” to hear prayers and a sermon. 4 He also urged his home community around Charlottesville to arrange a special day of fasting, prayer, and worship. 5

In 1779, Jefferson again called his state to prayer, asking the people to give thanks for “the glorious light of the Gospel, whereby through the merits of our gracious Redeemer we may become the heirs of His eternal glory.” 6 He further asked Virginians to pray that . . .

He would . . . pour out His Holy Spirit on all ministers on the Gospel – that He would bless and prosper the means of education and spread the light of Christian knowledge through the remotest corners of the earth. 7

Rick Perry did nothing more than what Thomas Jefferson did – a fact that Furlow ignores. Furlow further claims:

“The 1797 Treaty of Tripoli . . . said ‘the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion’.”

Furlow has lifted 19 words out of an 83 word sentence, thus making it say exactly the opposite of what it actually does say.

That 1797 treaty was one of several that America negotiated with Muslim nations during America’s first War on Islamic Terror (1784-1816), 8 in which five Muslim countries were indiscriminately attacking the property and interests of what they called the “Christian” nations, including America. But America sought to ensure the Muslims that we were not like the ancient European Christian nations – that did not hate Muslims because of their religious faith. Thus, the full sentence in that treaty states:

That 1797 treaty was one of several that America negotiated with Muslim nations during America’s first War on Islamic Terror (1784-1816), 8 in which five Muslim countries were indiscriminately attacking the property and interests of what they called the “Christian” nations, including America. But America sought to ensure the Muslims that we were not like the ancient European Christian nations – that did not hate Muslims because of their religious faith. Thus, the full sentence in that treaty states:

As the government of the United States of America is not in any sense founded on the Christian religion as it has in itself no character of enmity against the laws, religion or tranquility of Musselmen [Muslims] . . . 9

That is, we were not one of the Christian nations that held an inherent hostility toward Muslims. (See our full article on the 1797 Treaty of Tripoli and America’s first War on Terror.) Furthermore, in 1805 under Jefferson, that treaty was renegotiated and the clause stating that “. . . the United States is in no sense founded on the Christian religion . . .” was deleted. 10

Finally, Furlow complained that “the day of prayer [was] announced on the state website and the official invitation printed on Perry’s gubernatorial stationery.” But by 1815, some 1,400 official calls to prayer had already been issued by government leaders, 11 each printed and distributed at government expense – the Founders’ equivalent of using the “state website” and “gubernatorial stationery.”

In conclusion, despite what critics claim, history is clear that Rick Perry did exactly what the Founding Fathers themselves had done – on hundreds of occasions.

*Picture of Governor Perry is courtesy of the Office of the Governor. Permission to reproduce from this website for noncommercial purposes is freely granted. This permission statement must be included in any noncommercial reproduction.

1 Kate Shellnutt, “Lawyer: Perry’s plans raise First Amendment, church-state issues,” The Houston Chronicle, July 27, 2011.

2 Thomas Jefferson, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, Paul Ford, editor (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904), II:42, “Notice of Fast to the Inhabitants of the Parish of Saint Anne,” June 1774.

3 “Letters Between the Danbury Baptists and Thomas Jefferson,” WallBuilders, 1801, https://wallbuilders.com/resource/letters-between-the-danbury-baptists-and-thomas-jefferson/.

4 Thomas Jefferson, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Julian P. Boyd, editor (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950), 1:105-106, “Resolution of the House of Burgesses Designating a Day of Fasting and Prayer,” May 24, 1774.

5 Thomas Jefferson, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Julian P. Boyd, editor (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1950), 1:116, to the Inhabitants of the Parish of St. Anne before July 23, 1774.

6 Thomas Jefferson, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Julian P. Boyd, editor (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), 3:178, “Proclamation Appointing a Day of Thanksgiving and Prayer,” November 11, 1779.

7 Thomas Jefferson, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Julian P.Boyd, editor (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), 3:178, “Proclamation Appointing a Day of Thanksgiving and Prayer,” November 11, 1779.

8 See, for example, the 1787 treaty with Morocco; the 1795, 1815, and 1816 treaties with Algiers; the 1796 and 1805 treaties with Tripoli; and the 1797 treaty with Tunis. The American Diplomatic Code, Embracing A Collection of Treaties and Conventions Between the United States and Foreign Powers from 1778 to 1834, Jonathan Elliot, editor (New York: Burt Franklin, 1970; originally printed 1834), I:473-514.

9 Acts Passed at the First Session of the Fifth Congress of the United States of America (Philadelphia: William Ross, 1797), 43-44.

10 The American Diplomatic Code, Embracing a Collection of Treaties and Conventions Between the United States and Foreign Powers: From 1778 to 1834. With an Abstract of Important Judicial Decisions, On Points Connected with Our Foreign Relations, Jonathan Elliot, editor (Washington, D. C.: Jonathan Elliot, 1834), I:499, Art. 11, “Treaty of Peace and Friendship Between the United States of America and the Bey and Subjects of Tripoli of Barbary,” November 4, 1796, signed January 4, 1797

11 Deloss Love, The Fast and Thanksgiving Days of New England (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company 1895), 464-514, “Fast and Thanksgiving Days Calendar.”

* This article concerns a historical issue and may not have updated information.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!