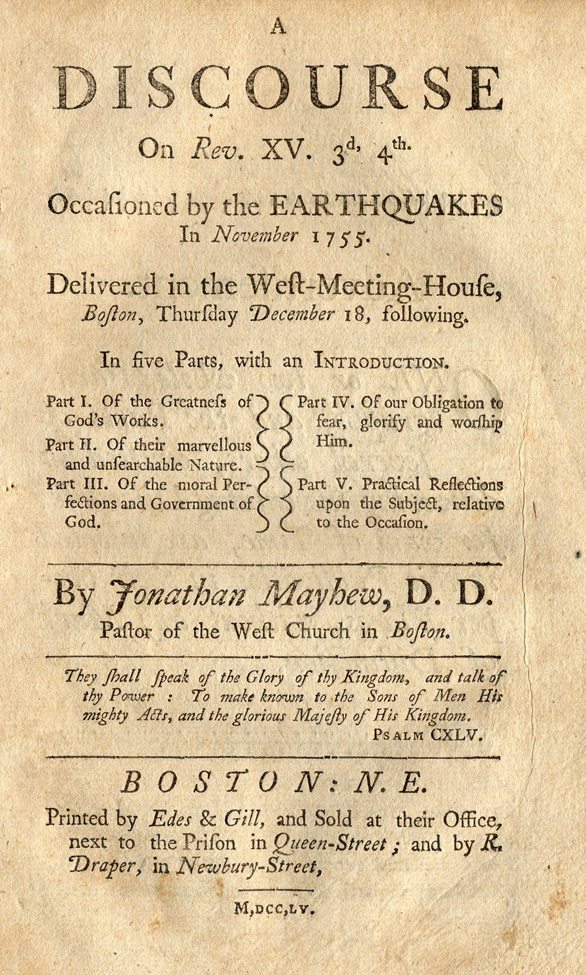

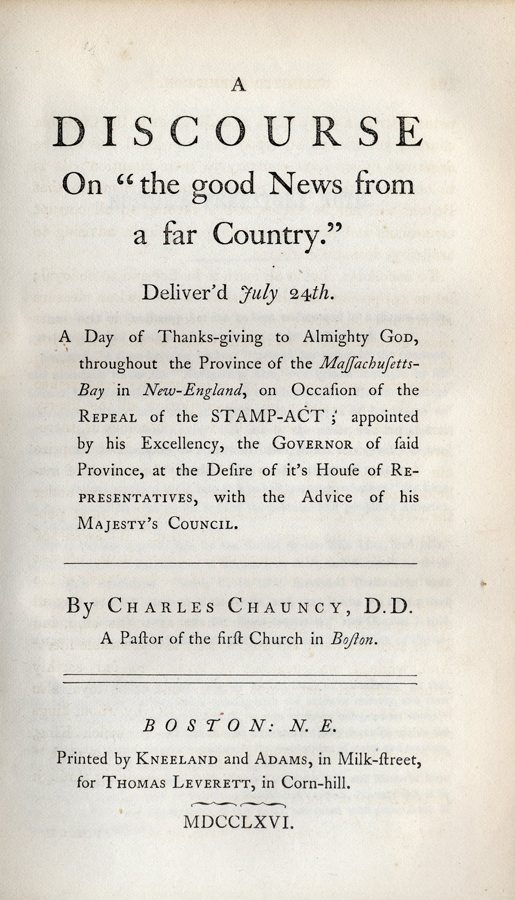

Rev. Jonathan Mayhew (1720-66) was a Massachusetts clergyman. He graduated with honors from Harvard in 1744 and began pastoring the West Church (Boston) in 1747. He preached what he considered to be a rational and practical Christianity based on the Scriptures. Mayhew was a true Puritan and staunchly defended civil liberty; he published many sermons related to the preservations of those liberties, including one immediately following the repeal of the Stamp Act entitled The Snare Broken (1766). Highly thought of by many patriots, including John Adams, who credited Rev. Mayhew with being one of the two most influential individuals in preparing Americans for their fight for independence. This sermon was preached by Jonathan Mayhew in November, 1755 on earthquakes that occurred in that year.

A

DISCOURSE

On Rev. XV. 3d, 4th.

Occasioned by the EARTHQUAKES

In November 1755.

Delivered in the West-Meeting-House,

Boston, Thursday, December 18, following.

By Jonathan Mayhew, D. D.

Pastor of the West Church in Boston.

They Shall Speak of the Glory of thy Kingdom, and talk of thy Power:

To make known to the Sons of Men His mighty Acts, and the glorious

Majesty of His Kingdom.

Psalm CXLV.

The Introduction.My Brethren,

THAT part of God’s holy word, upon which my Discourse at this time will be grounded, is in the XVth Chapter of the Revelation of St. John, the 3d and 4th Verses.

GREAT and marvelous are thy works, Lord God Almighty; just and true are thy ways, thou King of Saints! WHO shall not fear thee, O Lord, and glorify thy name I for thou only art holy: For all nations shall come and worship before thee; for thy judgments are made manifest.

THE uncommon and alarming occurrences of divine providence, which we have experienced in the late EARTHQUAKES, seem to demand a very particular and uncommon notice. And altho’ I have not, till now, invited you into the house of God, for that purpose; yet you, My Brethren of this society, are my witnesses, that I have not let these providential visitations pass wholly unregarded hitherto; but, more than once, taken occasion to speak of them; and improved them as an argument to enforce that practical religion and holiness of life, which is doubtless the moral end and design of them. So that many things which might have properly been said upon the occasion, have already been said in this place: Which must be my apology with those who may not hear, in this discourse, some things which they might, perhaps, expect in it. For I am not fond of repetitions, especially upon a subject which suggests such a great variety of reflections, as renders it quite needless to use any; and in discoursing upon which, it is, indeed, much more difficult to contract and suppress, than it is to enlarge.

And now we are assembled together, out of the common, stated course, to contemplate, and religiously to improve, these mighty and wonderful works of God, I know of no passage of scripture, fitter for the basis of a discourse upon such an occasion, than that which was just now read to you. This will naturally lead us from particular instances and manifestations of God’s power, to a more enlarged contemplation of his mighty deeds; and the glory and majesty of that kingdom, which “ruleth over all.”

There is such an elevation and dignity, such a divine energy and pathos, in this passage of scripture, as can hardly fail to raise and fix the attention of everyone. However, if anything farther should be necessary to this end, it will be found in the great occasion upon which, the glorious place where, and the blessed Ones by whom, the words are supposed to have been originally uttered. I shall, therefore, just remind you of these things, before I proceed to a particular consideration of the passage itself.

St. John the Divine, being in the Spirit, and rapt in the visions of God into future times, had a representation made to him of the woes and plagues, and the final destruction, which were to come upon those of the grand apostacy from the pure faith and worship of the Gospel; upon that antichristian power which is emblematically described by “a woman arrayed in purple, and scarlet colour, and decked with gold, and previous stones and pearls;”—and having upon her forehead a name written, MYSTERY, BABYLON THE GREAT, THE MOTHER OF HARLOTS, AND ABOMINATIONS OF THE EARTH.” 1 The plagues which St. John in his vision, or rather visions, saw coming upon great Babylon, (whatever is intended hereby) were successive; and arising one above another in greatness and terror, till at length “there were voices, and thunders and lightnings,” as he expresses it; and “a great Earthquake, such a one as was not since men were upon the earth, so mighty an Earthquake and so great. And the great city was divided into three parts; and the cities of the nations fell;” [i.e. of the nations which had drank of the wine of the wrath of her fornication,” chap. XIV. Ver. 8.] “and great Babylon came in remembrance before God, to give unto her the cup of the wine of the fierceness of his wrath.” 2 It seems to have been at this dividing of the great city into three parts by an Earthquake, attended, or immediately followed by a mighty fire; and not at her final overthrow, that St. John saw the “kings of the earth who had committed fornication with her;” the “merchants who were made rich by her;” and “every ship-master, and all the company in ships,”— “standing afar off, for fear of her torment, weeping and wailing, and saying, Alas! Alas! That great city—for in one hour so great riches is come to naught”!—and “crying when they saw the smoke of her burning, saying, What city is like unto this great city! And they cast dust upon their heads, weeping and wailing, and saying, Alas! Alas! That great city, wherein were made rich all that had ships in the sea—Rejoice over her, thou heaven, and ye holy apostles and prophets; for God hath avenged you on her!” 3 I say, it seems not to be her final destruction, at which these lamentations of some, and exultations of others, are made; that being to be effected by another, and still greater earthquake. And this her utter ruin was accordingly represented to St. John immediately after, by the following expressive emblem. “And a mighty angel,” says he, “took a stone like a great mill-stone, and cast it into the sea, saying THUS, with violence, shall that great city Babylon be thrown down, and shall be FOUND NO MORE AT ALL. And the voice of harpers and musicians, and of pipers, and of trumpeters, shall be heard no more at all in thee—and the light of a candle shall shine no more at all in thee; and the voice of the bridegroom and of the bride shall be heard no more at all in thee: for thy merchants were the great men of the earth; for by thy sorceries were all nations deceived.” 4 This is plainly her final overthrow and destruction. But who, or what is meant by Babylon the great, the woman arrayed in purple and scarlet, and styled the mother of harlots and abominations of the earth; who or what, I say, is intended hereby, I shall leave every one to conjecture; only just observing, that St. John tells us, she sitteth on “seven hills;” that she “reigneth over the kings of the earth;” and that “in her was found the blood of prophets, and of saints, and of all that were slain upon the earth.”

Now it is to be observed, that when St. John saw the “seven angels having the seven last plagues” 5 to pour out upon the earth, and particularly upon Babylon, he had also a vision of that glorious region where those were, “that had gotten the victory over the beast, and over his image, and over his mark, and over the number of his name—having the harps of GOD.” 6 And those blessed and happy persons it was, that he heard “singing this song of Moses the servant of GOD, and the song of the Lamb, saying, Great and marvelous are thy works, Lord GOD Almighty!” &c.

This is the anthem of the blessed, in those glorious mansions, with reference to the great events of which St. John speaks; while they anticipate the final overthrow of that power which “exalts itself above all that is called God, and that is worshipped.” And these circumstances being taken into consideration, they cannot but give an additional solemnity and dignity to this passage of scripture, in which there is such a native sublimity and grandeur, as cannot but strike, warm, and elevate the minds of all, except the grosly abandoned, or naturally-stupid.

To imagine that we, poor sojourners on earth, and inhabitants of clay, can, with a proper ardor, and an equally elevated devotion, bear a part in this song of praise and triumph, were, indeed, great vanity and presumption: But yet, not so much as to listen to it, and try to join the chorus, were certainly unbecoming our profession and character as Christians: For by becoming truly such, we claim a kindred with the blessed above; and are, in a sort, of one society with them; being the adopted children of Him, of whom the “whole family in heaven and earth is named.” In the strong and emphatical language of scripture, we are not only “fellow-citizens with the saints, and of the household of God”, here on earth; but we are “come unto mount Zion, and unto the city of the living God, the heavenly Jerusalem”:—“and to the general assembly and church of the first-born which are written in heaven”; and not only “to the spirits of just men made perfect”, but “to an innumerable company of “angels”; and not only to an not only to Jesus the Mediator of the new covenant, but “to God the Judge of all”. 7 If we are truly the disciples of Christ, we are now united by faith, by love, temper and affection, not only with saints, angels, and arch-angels above, but with our glorified Redeemer; and God himself dwelleth in us, and we in God. 8

Let us, therefore, bearing in mind the honourable kindred, and glorious relation, which we boast to the inhabitants of Zion that is above, “draw near with a true heart, in full assurance of faith”; even as “seeing him who is invisible”; and in his immutable veracity beholding and anticipating the great events represented in these visions of St. John; Let us, I say, now draw near in full assurance of faith, saying “Great and marvelous are thy works, Lord God almighty! Just and true are thy ways, thou King of saints! Who shall not fear thee, and glorify thy name! for thou only art holy: For all nations shall come and worship before thee; for thy judgments are made manifest!”

However, it is not my design at present, to consider these words with a particular view to the original design of them, as they are found in the visions of St. John: Had this been my intention, I should have been more exact and critical in pointing out to you the order and series, and the distinct parts of these visions; which is now needless: Because I intend to consider the passage as if it were independent, having no connection with any thing preceding or following. And being taken in this light, it will, I suppose, naturally enough lead us to such contemplations upon God, his works and attributes; and to such practical reflections as will perfectly coincide with the present occasion, and our design in coming to worship and bow down before the Lord our Maker at this time. For it naturally leads us, in the

FIRST place, to consider the greatness of God’s works; which proclaim his omnipotence. And

SECONDLY, their wonderfulness, and inscrutability.—Which two particulars are obviously suggested by the former part of the passage: “Great and marvelous are thy works, Lord God Almighty!”

THIRDLY, the moral perfections of God, in the exercise of which he governs the universe—Just and true are thy ways, thou King of Saints—thou only art holy—thy judgments are made manifest”.

FOURTHLY, The obligations lying upon all men to fear, glorify, and worship him—“Who shall not fear thee, O Lord, and glorify thy name—all nations shall come and worship before thee.” And,

LASTLY, It will lead us to some practical reflections upon those great and marvelous works of God, to make a religious improvement of which, we are now assembled together.

I shall be the shorter in the speculative, doctrinal part of my discourse, that I may have the more time for what I imagine will be more useful; I mean, the practical. And as I would hope there are none present, but what are present with a good intention, I should be sorry if any of my hearers should go away without being the better for what they hear. Accordingly, tho’ I will endeavor to remember that men have heads, as well as hearts and consciences; yet I shall aim rather at speaking to the latter, than to the former.

PART I.

Of the Greatness of God’s Works.

Let us then, in the first place, consider the greatness of God’s works; which proclaim his omnipotence. “Great—are thy works, Lord God Almighty!”—It is to be observed, that there are no powers in what we commonly call natural, secondary causes, but what are, to say the least, originally derived from the first; and no real agency in any that are wholly material. Activity or agency, properly speaking, belongs only to mind or spirit; and all those powers and operations which in common language are ascribed to natural bodies, are really effects and operations of the supreme, original cause. So that all the works which we behold, are, strictly speaking, God’s works; excepting those which are wrought by men, and other finite, intelligent beings. And even these latter are, in one sense, God’s works; because, though human agency, and the agency of other subordinate intelligences, is not to be wholly excluded and set aside; yet the active powers of these beings are both derived from, and upheld by Him, to whom “power” emphatically “belongeth” : 9 And also because all these subordinate agents, in all their operations, are under the control and dominion of the Almighty; and employed by Him to fulfill his purposes and pleasure. So that all the works which we behold are, in a large sense, and in the language of scripture, the doings and works of God. And accordingly the works of God, in the scripture phraseology, comprehend those of creation, of nature and providence; and whatever God does as the Lord and Governor of the world, whose kingdom ruleth over all.

And now, how manifold, and how great are these works! Whether we turn our eyes to the great and wide sea, or to the dry land; to the earth beneath us, or to the heavens above us, still we behold the mighty works of God. The ocean, which is shut up within limits which it cannot transgress, but when God gives it a dispensation for so doing; and wherein are things “innumerable both small and great beasts;” this is, surely, a great and astonishing work. And how mighty and powerful is that Being who made, and who has fixed bounds to it, saying, “Hitherto shalt thou come, and no farther; and here shall thy proud waves be stayed?” that Being, who holds the waters of it in the “hollow of his hand;” and whom its winds and surges obey? That Being, upon whom all its numerous inhabitants wait, that he may “give them their meat in due season;” which are troubled when he only “hideth his face,” and die when he taketh their breath?”

The dry land is not less full of his great works and wonders. Consider the beasts of the forests, and the cattle upon a thousand hills: Consider the huge, bulky animals, and the places where they range; the wide extended plains, and the “everlasting mountains” with their summits above the clouds; the mighty volcanoes in different parts of the world, whence rivers of liquid fire flow for miles into the ocean, like those of water from other mountains, as though they were going to contend for that place which God “founded” for the other element: Consider the concussion of an Earthquake, when half a continent with its neighbouring islands, and their surrounding seas, are once shaken; as though the land and water which God once separated, were again to be mixed and confounded together: Consider these works of God, I say, and tell me if they are not great!

Consider next, the air and atmosphere with which the whole earth is surrounded, and in which it is infolded as in a garment: Consider the numerous people, the winged inhabitants thereof, the fowls of heaven, which God daily feeds; and heareth when they cry 10 unto him, though we understand not their language: Consider the whirlwind and the tempest, when God “bows the heavens, and comes down, and darkness is under his feet;” when he “rides upon a cherub and does fly,” yea when he “flies upon the wings of the wind;” when he “makes darkness his secret place, his pavilion round about him, where dark waters are, and thick clouds of the skies”; when again, “at the brightness that is before him, his thick clouds pass, hail-stones and coals of fire;” when the Lord also “thunders, and the Highest gives his voice:”—yea, when he sends out his arrows, and scatters the [guilty, affrighted] nations; and shoots out his lightnings and discomfits them:” 11 Consider the returns of day and night, when we are alternately enlivened and cheered by the light, and covered with gloom and darkness: Consider the annually-returning seasons, when God alternately reneweth the face of the earth, and binds the fields and rivers in icy bands: Consider these works of God, I say, and then pronounce, whether they are great or not! “But lo, these are [but] parts of his ways; and how little a portion is heard of him!” 12

And if these works of God, which have now been hinted at, are great, and proclaim an all-powerful Being; what do those innumerable worlds do, which we behold revolving about us in such an admirable order! Who made those two great lights, the one of which rules by day, and the other by night? Who made the stars also? Who, those numerous, immense globes, compared to some of which, our earth is but as an atom, and our ocean as a drop of the bucket? Whose breath gave them all being? Whose hand gives them their motions? Who directs their courses? Who makes them know their proper places and distances, so as not to jostle, and wrack world on world? Whose hand constantly maintains their order, and sustains them in being? When you consider these things, surely you cannot avoid exclaiming,—“Great—are thy works, Lord God Almighty!” “For [verily] the invisible things of him from the creation of the world are clearly seen, being understood by the things that are made, even his eternal power and Godhead.” 13

But the works of God may come under another, and a mixed consideration, if I may so express it; I mean, as they are the doings of Him who is the righteous. 14 Sovereign of the world, as well as the Creator of it, and the Lord of nature. In which respect they are also great and illustrious; and equally so, perhaps, whether we consider the works of God’s righteous severity, or his works of mercy and goodness.

God’s works of judgment, which have been abroad, and made manifest in the earth, from one generation to another, may justly be termed great. Was not that, one such work, for example, when God rained fire and brimstone out of heaven, and consumed those wicked cities, Sodom and Gomorrha; and when the ground on which they stood, was sunk, doubtless by n earthquake, to a standing nauseous pool, as at this day? Was not that another such work, when he sent his Angel, and by him, destroyed in one night, such a vast multitude in the Assyrian camp? Was not that another, when he destroyed Pharaoh and his mighty host in the red sea?—that same Pharaoh, whom he raised up, for to shew in him his power, and that his name might be declared throughout all the earth?” 15 How many mighty works, of a similar nature to these, has God wrought? And what desolation has he made in the earth, in a way of judgment, since the foundations thereof were laid by him! But how great, more especially, was that work of God, when the fountains of the great deep were broken up? When the waters arose above the tops of the tallest mountains, and the flood of his anger came “upon the world of the ungodly, and swept them all away!”

But God’s works of goodness and kindness are not less great and illustrious, from age to age, than those of his just severity. The preservation of Lot, whose righteous soul was grieved with the filthy conversation of the wicked; and the preservation of Noah, a preacher of righteousness, with his family, in the ark, from whom the depopulated world was re-peopled after the deluge; these, I say, were great works of kindness and mercy. And was not that another such, when he led his chosen people like a flock out of Egypt, directing their march by a cloud by day, and a pillar of fire by night; till, at this command, the sea retired, and rose as a wall on either side of them, to let them pass? Was not that another work of great kindness to his chosen people, though attended with terror to them, when he gave them his laws and statutes at Sinai? When the mountain trembled and quaked; “and all the people saw the thundering, and the lightnings, and the noise of the trumpet, and the mountain smoaking; and—removed, and stood afar off?” 16 But to arise still higher; if the giving of the law by Moses his servant, and by the ministration of angels, was a great work of God’s kindness; how much greater is that of his giving the gospel of peace to the world, by his Son Jesus Christ, who is “made so much better than the angels, as he hath by inheritance obtained a more excellent name than they”? Is not the redemption of this sinful, apostate world, the work of God? or is it not emphatically a great one? Without controversy, great is this work of God, this mystery of godliness, which angels desire to look into! And at which not only hell, but heaven itself, and all that is therein, stands astonished, excepting Him whose work it is; and whom “the heaven, and the heavens of heavens cannot contain”!

There are other great things, both in the way of judgment and of mercy to be accomplished upon this stage, before the scene is closed. We have, perhaps, not seen as yet half the acts of this mighty drama. But we know the principal contents, and chief heads of the whole, by reflecting upon what is actually past and looking into that “sure word of prophecy” which shines as a light in a dark place, until the several great days and periods dawn in succession, and the “day-star [at length] arises in our hearts”. The chief articles and circumstances of the plot, if I may so express it, and the winding up of the whole, are in general made known to us by revelation. Babylon the great shall be utterly destroyed; which, surely, will appear to be a great work, whenever it is accomplished. God hath not utterly and finally cast away his ancient people Israel; they shall be recalled from their several and wide dispersions: And this work, which God will surely effect by his power and providence, will be equally great. It was not said in vain, “I will give thee the heathen for thine inheritance; and the uttermost parts of the earth for thy possession”; but when all Israel shall be saved, the fullness of the gentiles shall also come in; and there shall be “one fold and one shepherd”; and “every tongue shall confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God, the Father.

But how great, beyond expression, beyond conception, will the conclusion of this drama of ages be! When all the numerous actors shall appear before the visible Representative and “Image of the invisible God ”, 17 to receive his life-giving plaudit, or to be hiss’d and frown’d into perdition! When those who have acted their part ill, shall mix their cries and wailings in horrid discord, with the triumphant songs 18 and Hosanna’s of the redeemed, who have acted well; with the voice of the arch-angel and with the trump of God! When the scenes, the stage, and the mighty theatre itself, shall all drop and fall together!—I leave it to you to judge, whether these works of God will be great, or little!

To me it appears, that whether we contemplate the works of God in the natural, or in the moral world; or at once view them in that twofold light, in which I have now been considering them; whether we reflect upon those of them which are already accomplished, or look forward to those which shall infallibly be accomplished hereafter; still we cannot but exclaim—“Great—are thy works Lord God Almighty!” Nor will I lessen and debase these works of God, even so much as to ask, What comparison there is betwixt them, and the most august of those which are done by men, by the kings and potentates of the earth; to which trifles we sometimes ascribe grandeur and dignity!

PART II.

Of the marvelous, unsearchable nature of God’s Works.

It is now time for us to consider the wonderful nature of God’s works: For they are not only great, but marvelous!—“Marvelous are thy works, Lord God almighty!”—They may, indeed, be said to be marvelous, only in respect of their greatness; since no contemplative man can avoid being astonished at them, considered merely in this view. But they are also marvelous in another respect; viz. as we cannot penetrate into, or fully comprehend them, by reason of the narrowness of our capacities. 19 We can form no adequate, I had almost said absolutely, no conception at all, of creation, the first and original work of God. And it is but a little way that we can see into the nature and causes and reasons of things; the means and methods and ends, by and for which, many events are bro’t about both in the natural and moral world. As none can by searching “find out the Almighty unto perfection”; so neither can any perfectly understand and comprehend his works, even the least of them; and much less the greatest. “My thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways, my ways, saith the Lord. For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways, and my tho’ts than your thoughts”. 20 I know there are not wanting men, who pretend to have a thorough understanding of these matters; of almost all the works of nature and providence. But whether they are to be accounted wise men, or fools who know nothing as they ought to know it, we may learn in part from Solomon’s reflections upon this head: “I said I will be wise, but it was far from me,” says he. “That which is far off, and exceeding deep, who can find it out? I applied mine heart to know and to search, and to seek out wisdom, and the reason of things’ 21 —When I applied mine heart to know wisdom, and to see the business that is done upon the earth—then I beheld all the work of God, that a man cannot find out the work that is done under the sun: because though a man labour to seek it out, yet he shall not find it; yea farther, though a wise man think to know it, yet shall he not be able to find it.” 22 If a wise man cannot find out the work of God, it would be strange if fools could; nor, indeed, is there any greater evidence of folly, than the pretence of having done it. There is a reflection of much the same nature with this of Solomon, in the book of Job: “Which doeth great things, past finding out, yea, and wonders without number.” 23 “He is wise in heart, and mighty in strength—which removeth the mountains, and they know not which overturneth them in his anger: which shaketh the earth out of her place, and the pillars of heaven tremble: which commandeth the sun, and it riseth not; and sealeth up the stars: which alone spreadeth out the heavens, and treadeth upon the waves of the sea: which maketh Arcturus, Orion, and the Pleiades, and the chambers of the south.” 24

There is, indeed, such a thing as natural philosophy, which is of great use both to the purposes of life and godliness; and which, therefore, well deserves to be cultivated. However, the whole of what goes by that name, seems to be no more than the observing of facts, their succession and order; and reducing them to a general analogy; to certain established rules, and a settled course and series of events; called the laws of nature, from their steadiness and constancy. This, I say, seems to comprehend the whole of what we usually call natural philosophy. But after all the improvements that have been made herein, how many things are there in the natural world, which never have been, and perhaps never will be, reduced to any such general analogy, or to the common known laws of nature? How many phenomena are there, which we may call the irregulars, the anomalies, and heteroclites in the grammar, in the great book and language of nature, by which God speaks to us as really, as by his written oracles? Were the laws of comets, of inundations, of earthquakes, of meteors, of tempests, of the aurora borealis, of monstrous births? Were the particular laws and causes of these, and of a thousand other phenomena, I say, ever plainly discovered? I mean, so that they could be methodically calculated, foretold, and accounted for, as we calculate, foretell and account for common tides, eclipses, &c? No, surely; this has never been done by the greatest philosophers, with any tolerable degree of certainty and precision; tho’ there have been very ingenious, and even probable hypothesis concerning some of these phenomena. However, their causes and laws still remain very much in the dark: which may be owing, in part, to our not having critically observed a sufficient number of facts in each kind, from whence to draw general conclusions, and on which to form theories. For there is doubtless as regular an order and connection of these facts and effects, in nature, whether actually seen and known by us or not; and therefore as truly a course of nature with respect to them, as there is of, and with respect to, the most common and familiar. But this connection and order is, as yet, too recondite and hidden for human penetration, so that we can do but little more than form conjectures about these things. These works of God may, therefore, justly be called marvelous, past finding out; and these wonders of nature are also without number.

But upon supposition that all those works of God, which we call the works of nature, could be brought to a common analogy, and methodically arranged under certain known laws, as some of them are, so as to admit of a solution as plainly, and in the same sense, that eclipses, common tides, or any other natural phenomena do; even upon this supposition, I say, our knowledge would still be very imperfect; and the works of God, still marvelous to us. For it is to be remembered, that these general laws, by which we think to account for all other things, are themselves mysterious and inexplicable. Who, for example, can, without vanity and presumption, pretend to understand the great law of gravitation; the most general and extensive one, which we know of in nature? Who, I say, can, without the utmost vanity and presumption pretend to a thorough understanding of this law? Especially after a Newton has confessed his ignorance of it; and expressed his doubts, whether it were the effect of God’s immediate power, operating regularly upon every particle of matter throughout the universe; or whether it were the effect of some intermediate, natural cause, unknown to us? Some subtle medium pervading all natural bodies and substances? And though the latter were known to be the case, still the same, or rather a greater difficulty would recur, respecting that prior, and natural cause; and so on in infinitum; or, at least, ‘till we come to that great First Cause and Agent, who is the “least understood” of all things. For He must needs be more incomprehensible even than any of his marvelous works, since our first knowledge of Him, is learnt from them.

What is said above concerning the law of gravitation, is equally applicable to all others, which we call natural causes, or laws of nature: They are all really incomprehensible. We can no more penetrate into the true reason why a spark of fire, rather than a drop of water, should cause an explosion when dropped on powder; than we can tell why a stone, left to itself in the air, should fall, rather than ascend: i.e. we cannot do it at all. Thus it is as to all natural causes in general. So that, as was intimated above, our knowledge would be very imperfect, even though we could easily reduce all the phenomena in the natural world, to known, general laws; as it is certain we cannot. We should then know nothing but facts and effects, their regular succession and order. For though we speak of the natural, visible causes of many things; yet these causes seem to be plainly effects themselves; and the real cause of them, and of all things, is hidden, quite veiled from mortal fight; “though He be not far from every one of us.” 25 “Behold, we go forward, but He is not [visibly] there; and backward; but we cannot perceive Him: On the left hand, where He doth work, but we cannot behold Him: He hideth Himself on the right hand, that we cannot see Him. But He knoweth the way that we take!” 26

That cause which acts thus regularly, mightily, and marvelously, every-where; must needs be all-wise, all-powerful, and omnipresent: And into His incomprehensible agency, non-pluss’d philosophy itself must ultimately resolve all natural effects, together with their apparent, visible causes.

So that the whole natural world, is really nothing but one great wonder and mystery. It is not only those which we, in common language, call the great works of God, that are marvelous and inscrutable; but the least of them also. We are even an astonishment to ourselves. For we are “fearfully and wonderfully made: Marvelous are thy works, and that my soul knoweth right well! My substance was not hid from thee, when I was made in secret, and curiously wrought—Thine eye did see my substance yet being unperfect, and in thy book all my members were written, which in continuance were fashioned!”— 27 The most common, the least, and the most inconsiderable effects of God’s power, which we behold, baffle human wisdom and penetration. A flower of the field, which springs up in the morning, and at night is withered; the mite that is undiscernable to the naked eye; every atom or mote that flies in the sun-beams, or is wafted by the breeze, contains marvels and wonders enough to non-pluss the greatest sage. These are all the works of God; and all marvelous: And tho’ we do not call them great; yet the least of them proclaims the wisdom, the eternal power and god-head, of the Creator.

The works of God, as he is the moral 28 Governor of the world, are also marvelous and unsearchable; at least many of them are so. The second, or the new birth, which is of the Spirit, and which we are all so much concerned to experience, is not less mysterious than the first. For “as thou knowest not what is the way of the Spirit, nor how the bones do grow in the womb of her that is with child; even so thou knowest not the works of God who maketh all;” and by whom we are “created a-new in Christ Jesus”. And altho’ our Saviour cautioned Nichodemus not to “marvel” at his saying. “Ye must be born again”; yet he immediately compares this mysterious work of the Spirit, to one of the visible effects of God’s invisible power in the natural world; which tho’ one of the most common, is yet truly wonderful—“The wind bloweth where it listeth, says he, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit”, 29 of that Spirit, which is ever operating both in the kingdom of nature, and of grace. For we may apply to all these operations and effects, however different they may seem, what the apostle says of the different kinds of miraculous gifts in that age of the church—“All these worketh that one and the self-same spirit”. 30

The dispensations of God’s providence towards mankind, have all some-what that is mysterious and incomprehensible in them. We cannot see into all the connections and dependences of things and events in the moral world; so as to give a clear account and solution of them. Difficulties and objections will remain, thro’ our ignorance and short-sightedness, against the scheme and methods of God’s dealing with the children of men, after puzzled theology has done its best. In which respect it is said, that “clouds and darkness are round about Him,” altho’ “righteousness and judgment are the habitation of his throne” 31 Amongst the marvelous, unsearchable dispensations of God to the world, considered as the moral Governor of it; we may particularly reckon our being subjected to sorrow, pain and death, “through the offence of one;” and our restoration to happiness and life eternal, by the obedience unto death of a far Greater, “the Lord from heaven:” God’s calling the Jews of old to be his peculiar people; their rejection, with the circumstances attending it; and their preservation in their present dispersed state: The sufferings to which good men are sometimes subjected, while the wicked are prospered, and “flourish like a green bay-tree:” The utter overthrow and ruin of some wicked nations, while some others, to appearance as wicked, if not more so, are preserved, and favoured with the smiles of providence. These and many other dispensations of providence, both past and future, we cannot penetrate to the bottom of, or clearly see into. So that whether we consider God’s natural works, or his moral; or consider his works at once in both these lights, they are not only great, but marvelous. “No heart can think of these things worthily: and who is able to conceive his ways? It is a tempest which no man can see; for the most part of his works are hid. Who can declare the works of his justice? Or who can endure them? For his covenant is afar off, and the trial of all things is in the end.” 32 Whether, therefore, you are a true philosopher, a true Christian, or both, as St. Paul was, still you must adopt his language?—“O the depth of the riches, both of the wisdom and knowledge of God! how unsearchable are his judgments, and his ways past finding out! For who hath known the mind of the Lord? Or who hath been his counselor? Or who hath first given unto him, and it shall be recompenced to him again? For of him, and through him, and to him are all things: To whom be glory for ever Amen!” 33

PART III.

Of the moral Perfections and Government of God.

But though human wisdom cannot scan or comprehend the great and marvelous works of God; yet we do, or may know so much, both of Him and them, as may serve the ends of practical religion; which is the end of man.—So that though we should guard against vanity on one hand, yet we should equally guard against false modesty, or skepticism on the other. We are not shut up in a vast, dark labyrinth, without any crevice or clue at all. We see at least some glimmerings of light; and if Theseus-like, we follow the club which is actually given us, it will lead us out of this darkness into open and endless day. But not to dwell upon metaphor and allusion: God gives us such notices of himself by his works, by the course of his providence, by our reason, and by his word, that though we must confess our ignorance of innumerable things, still we may say with confidence—“Just and true are thy ways, thou King of saints!”—“Thou only art holy!”—“Thy judgments are made manifest!”

Amidst all our darkness and ignorance, we see enough, unless we are willfully blind, to convince us, That God is a moral Governor; or that a moral government is actually established, and gradually carrying on in the world; and that we ourselves are the subjects of it. Had we only the light of nature to direct us, we might by properly following it, conclude with a good degree of certainty, That God is a beneficent, true, and righteous being; the patron of good men, and the enemy of the wicked; and one who will, sooner or later, give to every man according to his deeds. For is not the Creator, and Upholder, also the Lord and Judge, of all? Or “shall not the Judge of all the earth do right!”—“The work of a man shall he render unto him, and cause every man to find according to his ways. Yea, surely, God will not do wickedly, neither will the Almighty pervert judgment! Who hath given him a charge over the earth? Or who hath disposed the whole world!” Thou these words are found in one of the books of revelation, yet the passage is really the language of nature: Nor, indeed, do I remember that any have supposed that Elihu who utters them, was inspired. These are the sentiments which naturally arise in an improved, virtuous mind, upon contemplating the works of God; the great, independent Being, and source of all things.

The moral perfections which we usually ascribe to God, seem to have a connection with those natural ones, which must necessarily belong to the original cause of all things; particularly with independency, or self-sufficiency, infinite wisdom, and unbounded power. It is scarce, if at all possible, to conceive of that Being who has these natural perfections, to be false, cruel, or unjust; or to be otherwise than faithful and true, holy and righteous. So that these latter attributes are, in some sense, deducible from the former. But this argument, usually called by metaphysicians, the argument a priori; this argument, I say, in conjunction with some others, will appear conclusive to every thoughtful and honest man: I mean, particularly, those arguments which may be drawn from the moral nature which God has given us; from the consciousness we have of right and wrong; from the law written in our hearts; from our immediate sense of good and of ill desert; and from the vestiges and traces of goodness and righteousness, which we plainly see in the constitution, and in the course of nature; and the dispensations of God’s providence towards men. For although the judgments 34 of God are not now made manifest in so great a degree as they will be at that period, to which the passage my discourse is grounded upon, relates; yet they are discoverable in some degree at present, by what we daily see and experience. Although there may be room left for men of perverse and corrupt minds to cavil against, there is really none for men of fair, ingenuous minds to doubt of, much less to deny, the morality of the government we are now under, the things which have been just hinted at above, and for a particular discussion of which, there is not time, being duly considered.

However, I must just observe, That as the light of nature shows the world to be under a moral government and Governor, faithful, good, and righteous; so revelation, not only sometimes asserts this, but always supposes, and takes it for granted, as the foundation and ground-work of all; as the basis on which the whole fabric stands. The whole scheme of our redemption by Christ, from first to last, in all its parts, is grounded upon this supposition. For certainly the Christian revelation presupposes mankind to be antecedently under the righteous government of God, and accountable to him for their actions,; since it proposes a method for our escaping the punishment due to the transgressors of His laws. It supposes God to be good and merciful; since this very method of salvation for sinners, could originate in nothing but goodness and mercy—[“God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son,” &c.—] It either asserts, or takes it for granted, that God does, in the course of his providence, even in all ages, reward and punish here, in some degree, the good and the wicked respectively, both individuals and whole communities. But the Christian revelation is more especially a confirmation of the morality of God’s government, as it so expressly teaches us, That there is a time of retribution approaching, wherein the righteous shall receive a glorious recompense of reward; and the wicked, the punishment which their sins deserve, though delayed for a season; and all men in general, receive the things done in the body, whether good or bad. This will be the completion and perfection of that moral scheme and plan, which is already established; which is carrying into execution from age to age; and which is plainly discernable to those who are not loth to see and acknowledge it; discernable, even from our own frame and constitution, and from every day’s experience. For we find a law of righteousness written on our hearts, though we may try to expunge and disannul it, by reason of the law of sin that is in our members, and which wars against it. We find ourselves entrusted in some sense, by the Author of our being, with our own happiness; we find that virtue is the road to felicity; and vice, to misery here. Nor is there the least presumption in reason, against the general doctrine of revelation, That our good and bad deeds, or at least the effects of them, shall follow us into another state, where this moral scheme shall appear in its perfection, both in the goodness, and in the righteous severity of God. For there may be certain grand periods in the moral, as well as in the natural world; both a seed-time, and a time of harvest; in the latter of which, he that has before “sowed to the flesh, shall of the flesh reap corruption;” and he that hath “sowed to the spirit, shall of the spirit reap everlasting life.” And you know who has said in this allegorical way,—“The harvest is the end of the world,” &c.

PART IV.

Of our Obligation to fear, glorify and worship God.

This passage of scripture leads us, in the next place, to consider the obligation which we are under to fear, glorify and worship God; which obligation results from his perfections, and the relation in which he stands towards us—“Who shall not fear thee, O Lord, and glorify thy name?—All nations shall come and worship before thee”. And who can doubt his obligation to do thus, if God is such a Being as he has been imperfectly represented to be, in the foregoing parts of this discourse? If he is indeed the “Lord God almighty”? If he is the “King of Saints”? if his ways are all “just and true” if he “only is holy”? if his “judgments” are, and will be, thus “made manifest”? What man? What nation, shall not fear, adore and worship a Being, so gloriously great, powerful, just and good!

There is One, and but One, to be feared. And certainly you can be in no doubt, Who that One is. There is a harmony and uniformity of design visible in the works of nature and providence, which shows that all originally proceeds from, and is governed by ONE: Which dictate of nature, or reason, is abundantly ratified and confirmed by revelation. For it is as clearly and expressly declared, That there is but “One God”, as it is that there is but “one Mediator between God and men”: 35 as plainly, That there is but One God, the Father, of whom are all things”, as that there is but “One Lord, Jesus Christ”. 36 And the most distinguishing title or characteristic of this One God, in the New Testament, is, “The God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ”. 37 He, undoubtedly it is, that exclusively of all other beings, is here styled the “Lord God Almighty”, the “King of Saints”; and of whom it is said, that He “only is holy”, &c. And certainly it is equally our duty and our interest to fear, glorify and obey, this “One Lawgiver, who is able to save and to destroy”; 38 the “Father of all, who is above all, and thro’ all, and in us all”; 39 who is God omnipresent, even “from everlasting to everlasting”. Is it not altogether reasonable for us, weak, dependent, imperfect creatures, to reverence, worship, and obey Him that made us, and all things? Him, in whom “we live, and move, and have our being? Him, in whom all conceivable perfections, whether natural or moral, are united, even in an infinite degree; (if it be not a solecism to speak of degrees in infinity, and perfection) and who governs the universe in the exercise of these perfections? Men who do not thus fear and serve God, must counteract their own nature; I mean their rational, intellectual and moral nature, the light and dictates of their own consciences. For they cannot but see and feel, in some degree at least, that they ought to do thus; that they are under an indispensable obligation, in point of reason and fitness, as well as interest, to do it; so that, if they do it not, but the contrary, they must needs be “without excuse”, and “condemned of themselves”.

It is no sooner known that there is really such a glorious Being existing, than every man’s own heart, even antecedently to any formal, rational process, tells him in general what his duty is; what is the proper, practical inference; how he ought to stand affected towards God; and what part he has to act. And if men will but duly consider their own frame and make, their reason will, upon a little reflection, ratify these first dictates of their hearts and consciences. Are we not so constituted by the Author of our being, that great power excites a certain awe in us, unless we are, or at least imagine ourselves to be, more powerful than He, in whom we observe it? Does not a common man almost shudder at the thoughts of a giant; one of the sons of Anak, even tho’ he knows he is long since dead, and can do him no harm? Does not superior wisdom amongst men, naturally attract respect and reverence? I mean, from all who have themselves wisdom enough to discern it? Is not this our reverence of superior wisdom heightened, when that wisdom is in conjunction with veracity, and justice duly tempered with goodness and mercy? I mean, so as not to degenerate into cruelty on one hand, nor into any childish weaknesses on the other? Is not our reverence still heightened, when these qualities are found in age? In one, whose head was hoary, even before we saw the light? Is it not still increased, if this same person is our prince and lawgiver, and one on whose protection we depend? (a supposition which, God be praised! We may now make with some propriety—) Yea, would not our reverence of him be still greater, if we were in his presence, and under his eye, than while he is absent from us, or we from him? Yea, I will ask once more, whether our respect and reverence to such an earthly sovereign, would not be greater, if we actually saw him exerting his great and good qualities, in redressing the wrongs of his subjects; in punishing the evil and rebellious, and protecting and patronizing the good; than while we only believe or hear that he does thus, as occasion and opportunity are offered? If I were not almost tired with asking, and you, perhaps, with hearing questions, I would still ask, whether, all these qualities, being united in the same person, and all these circumstances concurring to heighten our esteem and reverence, we should not, of course, resign ourselves up to the will of their object, and cheerfully obey him; thinking ourselves happy in his favour, 40 and dreading the thoughts of his just displeasure as one of the greatest of evils? I presume there is no man, who understands these questions, which are not indeed difficult to be comprehended, but what would answer them all in the affirmative, if he sincerely spoke the dictates of his heart, without indulging to chicanery, and to the making of subtle evasions. It would evidently be fit and reasonable for us to be affected towards such a person as has been described, in the manner above expressed; and you would think that man very unreasonable, a kind of monster notwithstanding his human shape, who did not thus reverence, and thus demean himself towards, so great and good a personage, standing in such a relation towards him.

Here, then, you have the ground-work, and principles of religion in your own frame and constitution; so that the longer you reflect, the more reason you will see to fear, and adore God, and to keep his commandments. For is there any being so powerful as the “Lord God Almighty?” Is there any one so wise as the “only wise God?” anyone so righteous and faithful as He, all whose ways are “just and true?” any other so pure and spotless as He, who “only is holy?” Any one so venerable in respect of his years and age, as the “Ancient of days,” who “was, and is, and is to come?” Is there any one so properly our sovereign, and lawgiver, as the “King of saints,” whose “kingdom ruleth over all?” anyone who is “through all, and in us all?” In sine, is there any one, whose judgments, and effects of them, are and will be made so manifest before our eyes, as His, who is “the Judge of all the earth?” His, whose providence now governs the world, and who will hereafter judge it “in righteousness, by that man whom He hath ordained”?—Who then shall not fear and reverence? Who, not glorify and praise? Who, not obey, Him? Shall not all nations come and worship before him, before whom “all nations are as nothing;” and “Lebanon is not sufficient to burn, nor the beasts thereof sufficient for a burnt offering!” 41 Your obligation thus to fear, glorify and worship the great God, results so immediately and plainly from his nature, and your own, and the relation in which he stands towards you, that you must, I had almost said, uncreate your Creator or yourselves, and thereby destroy this relation, before your reason will absolve your from such obligation. But what I intend is, that while God is God, and men are men, they are bound by all the ties of reason religiously to fear, and worship, and obey Him.

There are some things, even at first view so plain and obvious to fair and honest minds, as almost to preclude any reasoning or augmentation concerning them. The obligations to practical religion in general, supposing there is really a God, seem to be of this kind. They can scarce be made plainer by reasoning, than they are without it; as the sun will not become the more visible to a man who opens his yes, by all the reasoning’s of philosophers about it. Accordingly, in the passage of scripture now under consideration, there is no formal ratiocination; but only a warm, devout and rapturous exclamation, the natural dictate of a good heart, and which will immediately find its way to the hearts and consciences of all men, who have not very grossly corrupted and debauched their own nature—“Who shall not fear thee, O Lord, and glorify thy name.”—“All nations shall come and worship before thee!”—However, there is, I suppose, somewhat of the prophetic kind in these last words: They do not only express what is right and fitting; but also suggest what shall eventually come to pass, after God’s judgments are made manifest in the original sense of the passage; that sense which was mentioned in the introductory part of this discourse. For all nations shall actually come and worship before God, when Babylon the great is destroyed.

The obligations we are under in general religiously to reverence, worship and obey God, being, as I suppose, sufficiently evident: it may be proper to subjoin here, hat God’s holy word ought to be the rule of the worship, service and obedience which we pay to him. How greatly the Christian religion has been, and still is corrupted, in most countries where it is professed, even to the introduction of the grossest superstitions and idolatries, there is neither time nor occasion now particularly to mention. It becomes us to take heed that we do not ourselves add to, or even countenance, in any degree, these corruptions. Especially if we have any well-grounded persuasion upon our minds, what is intended in the new testament by Babylon, that “mother of harlots and abominations,” we should keep at a distance from her; for God will, sooner or later, make her plagues wonderful, as well as manifest. “What concord hath Christ with Belial, says St. Paul: 42 —And what agreement hath the temple of God with idols?”—“Wherefore come out from among them, and be ye separate, saith the Lord; and touch not the unclean thing, and I will receive you; and will be a Father unto you, and ye shall be my sons and daughters saith the Lord Almighty.” A corrupt and idolatrous church is not the less to be separated from, because she dishonors Christ and his religion by calling herself after his worthy name: And it well deserves to be remarked, That St. John, in the midst of the visions which he had of the woes coming in succession upon Babylon, now “become the habitation of devils, and the hold of every foul spirit, and a cage of every unclean and hateful bird,” 43 tells us that he heard a “voice from heaven, saying, Come out of her, my people, that ye be not partakers of her sins, and that ye receive not of her plagues.” 44

I hope, I shall give no just ground of offence to any, (which I should be very loth to do) by adding here, That for the same general reason that we ought not to go wholly over to that apostate church which the scriptures sometimes intend by the name Babylon, we ought not to conform to, or symbolize with her, in any of her corruptions, and idolatrous usages: but to keep at as great a distance from them as possible, by strictly adhering to the holy scriptures in doctrine, discipline, worship and practice. Nor does this seem to me to be a needless caveat, even in any protestant country whatever: For I am verily persuaded that there is not now, nor has been for many generations past, any national church, wholly and absolutely free from these corruptions. Notwithstanding our boasted reformation, it is, alas! But too evident that we are not yet past that long, dark and corrupt period of the Christian world, to which St. John refers, when speaking of mystical Babylon he says, That “All Nations had drunk of the wine of the wrath of her fornication; and that the Kings of the earth had committed fornication 45 with her”. 46 We should therefore conform to our Bibles, whatever becomes of the decrees of councils, popes or kings; tho’ they should, like one of the ancient kings of literal Babylon, set up their golden images and idols, and command us to “fall down and worship, at what time we hear the sound of the cornet, flute, harp, sackbut, psaltery, dulcimer, and all kinds of music”; 47 yea, tho’ they should point us to their “furnaces, heated one seven times hotter than they were wont to be heat”. 48 We read of a still more terrible fire, into which the “beast” shall be cast, “and with him the false prophet that worketh miracles before hi, with which he deceiveth them that receive the mark of the beast, and them that worship his image”. 49 But blessed is he that feareth, and glorifieth, and patiently worshipeth the “Lord God almighty”, the “King of Saints”, according to his word and institutions; even he that doeth His commandments, “that he may have right to the tree of life, and may enter in thro’ the gates into the city. For without are dogs, and sorcerers, and whoremongers, and murders, and idolaters, and whosoever loveth and maketh a lie. 50

PART V.

Practical Reflections upon the Subject, relative to the Occasion.

But it is perhaps more than time for me to proceed to the practical part of my discourse; and to apply the subject to ourselves and the present occasion. We have lately had a very striking and awakening memento, or rather example, of the greatness, and the marvelous nature of God’s works; when this continent, for eight or nine hundred miles together, with the neighbouring islands, and the Atlantic ocean, were t once shaken, and thrown into convulsions. That this is truly the work of God, and that it is both a great and marvelous one, I suppose I need not go about to prove to you, after what has been said above. Indeed, if I mistake not, you all discover’d plainly enough, that this was your sense of it, at the time of this event, to say nothing of what you have done since, or do at present.

You think then, that an Earthquake is one of the mighty works of God; You think justly. And whenever you behold, or experience these his great and marvelous works, it may well excite your fear of him: for how gloriously terrible in majesty is that Being, who is able to produce such astonishing effects! But shall I tell you, that you every day behold greater works than these? Far more illustrious displays and manifestations of the power of God? This is really the truth. Did not God create the whole earth? Does he not daily uphold it in being, with all that it contains? And is not the creating and upholding the whole, a far greater work than shaking and removing a small part of it? Certainly it is. You can, therefore, never look upon the earth even when it does not quake, without being silently admonished to fear and obey him that made it; as truly admonished to do so, as when the “pillars of heaven tremble”, and the “highest gives his voice”; tho’ some may, perhaps, have never attended to this silent and constant admonition. But when you extend your views beyond this earth, to the numerous worlds around; when you look up in a serene night, and attentively behold this gloriously “dreadful All”; when you see “worlds on worlds,” and systems on systems “composing one universe;” when you seriously contemplate Him, whose hand once form’d, and still grasps, and moves, and directs this stupendous and amazing Whole; whenever you do thus, I say, you cannot but think even an earthquake, or the earth itself, comparatively speaking, a little work; a far less, than innumerable others. One principal reason why an earthquake appears to be such a great and stupendous work as it does to most people, is because instead of enlarging their minds by contemplating objects that are truly great, they narrow them by attending only to little things; such toys and trifles, I mean, as are found in this world, the riches and vanities of it; the pomps, the thrones, the scepters and diamems of kings. It is not strange that they who can think such little things great, and admire them as being so; they whose thoughts are ever groveling on the ground on which they tread, and never ascend above it, it is not strange, I say, that such persons should be astonished at the grandeur of an earthquake, even though they had nothing to fear from such an event. For it must be confessed that there is nothing, I mean no merely natural occurrence or event in this world, which cn more properly be called great, than such an one. Abut to a contemplative man, as was intimated before, there are many other works of God, which still more fully declare his power and glory; and which are therefore to such men, louder calls to reverence and obey him; tho’ less calculated to minister terror and amazement.

When we behold, or reflect upon, the great and marvelous works of God, all-powerful, wise, holy, just and good the effect hereof should not be the exciting in us a fruitless admiration of, and astonishment at them; but the exciting in us a due reverence and esteem of Him, whose works they are; till from admiring them, we come to admire, to fear, to love nothing besides Him, the Lord God almighty, the King of saints, who only is holy. For all his works are little, in comparison of Him; and can claim no regard or notice, any farther than they may help to lead us to the knowledge, and to worthy conceptions of Him. And unless our thoughts are thus led to God from his works, so as to inspire us with the reverence, love and admiration of him, we had almost as good stare at puppet-shows, as contemplate the heavens.

An earthquake is indeed very peculiarly adapted to rouse and awaken the minds of the inconsiderate, and of those who forget God; and to beget in them that fear of him, which is “the beginning of wisdom”; more adapted to this end, even than the greater and more constant manifestations of his eternal power and godhead. This is evident from the effect: for many who disregard these constant displays of God’s power, and other perfections, from year to year, are yet alarmed by an earthquake, and impressed with a serious sense of religion. How many, who were perhaps never excited to fear God, by beholding the heavens, which declare his glory, “the moon and the stars which he has ordained,” have been excited hereto, b these late occurrences of his providence? Where is that sinner, so tho’tless, so stupid and abandoned, whose “flesh did not tremble for fear of God, and who was not afraid of his judgments,” when the earth so lately shook and trembled? Nor were these fears excited in them without the highest reason, when we reflect that God has often declared in his holy word, that earthquakes are, sometimes at least, sent in his righteous displeasure; not merely for the warning and admonition of some sinners, but for the destruction of others: And when we reflect what amazing desolation he has often actually wrought by hem in the earth! Some recent examples and instances whereof, we have indeed, now within a day or two, heard of in Europe. The particulars of which are so awful and terrible, that I shall not now enumerate them; for I have no inclination, were it in my power, to throw you in a panic; but only to reason calmly with you “of righteousness, temperance and judgment to come”; of your obligation to fear and obey Him, whose works are thus great and marvelous, and his judgments thus made manifest in the earth. 51 It is not only natural, but just and proper for wicked men to tremble and to be afraid, when God thus ariseth to shake terribly the earth, and his judgments are abroad in it. And if their own lives are spared, they ought not only to tremble at, but to learn righteousness from, these alarming events. This, thro’ the tender mercies of our God, is the case of those wicked men who are here present before Him, if there are any persons present, to whom that character belongs. Would to God, there were not!—

But upon the presumption that there are at least some such; (not an unnatural or uncharitable presumption, I conceive, considering the largeness of the assembly, and the present state of religion in the world) Upon this presumption, I say, let me be allowed to address myself briefly and seriously to such unhappy men; not as their enemy, God forbid! But as their friendly monitor—Let your hearts and tongues be filled with the high praises of God, that your lives have been thus graciously preserved; and that the thing which you so greatly and justly feared, not to say deserved, is not come upon you. What distress and anxiety were you lately in! Where, alas! And what would you now have been, had the earth opened her mouth and swallowed you up? Or had your falling houses crushed you to death? Examples of both of which, there have been many in former times, and some very lately. Had either of these been your own case, I say, where, and what would you now have been!—Wretched, and accursed of God, in that region of darkness and despair, where the rich man lift up his eyes being in torment! But in the time of your apparent danger, when “the sorrows of death compassed you, and the pains of hell gat “hold upon you,” 52 God who is long-suffering and rich in mercy, as well as holy and all-powerful, “inclined his ear;” 53 and you are still among the living. What then will you “render unto the Lord for all his benefits towards you”? 54 and particularly for this? Will you not now praise and glorify his name? The mariner (at his “wits end” while the storm beats upon him, and when every sleeper “awakes and calls upon his God:” the mariner, I say,) when the storm is over, blesses Him whom winds and seas obey, that he has escaped foundering and ship-wrack. Thus it becomes you to do, whom God has mercifully preserved when in at least equal perils by land. Did you not make your vows to him in the time of your distress? And will you now pay them? 55 Will you not forever hereafter praise and reverence, worship and serve the Lord God Almighty, the King of saints, and the Preserver even of sinners, tho’ He who only is holy? Will you not now, at length, break off your sins by righteousness; and implore the forgiveness of them through him, in whom God is reconciling the world unto himself? Did you not resolve to do thus, in the late time of your terror and amazement? And will you not now perform these vows and engagements? Were there not some particular sins, that more especially then flew in your faces; & which you then more particularly resolved to forsake, if God should spare your lives? Were there not some particular duties, with the omission of which your consciences then especially accused you; and which you particularly resolved to practice for the future, if you should hae an opportunity for it? Your consciences, which are always the voice of God within you, were, I doubt not, then awake, and plainly told you the truth. It was no Delphic, ambiguous response, which they then gave; but one clear and distinct, convincing and infallible as the oracle of God. Remember, O man! What that great oracle, conscience, within thee, pronounced at that time; take the warning,, and obey the heavenly voice! Presume not to repeat those sins, with which it then charged you; nor to omit those duties, your former neglect of which then gave you disquietude.

It is not only melancholy, but astonishing, to observe how soon wicked men often get rid of their just fears and apprehensions of the divine displeasure, and break through their better resolutions, when they no longer see the rod of God held out, and shaken at them. They act as if they thought he then ceased to be that just, and holy, and almighty Being which they apprehended him to be, while they thought themselves in immediate danger of his judgments; as if they thought he was not “angry with the wicked every day”, but only when there are some alarming occurrences in the course of his providence; and so return to their former vices and impieties, almost as soon as the particular evils and dangers they apprehended, are removed. Suffer me therefore to warn you against this folly; and to beseech you, as you value the salvation of your souls, not to suffer that religious sense of things, which was lately awakened in you by these awful occurrences, to wear off; and so return to your old crimes. At the time of, or immediately after, the late earthquakes, did vicious men find in themselves any inclination to repeat their old sins; and to break the commandments of God? Did the drunkard then think of his bowl or bottle? Did the whoremonger and adulterer then find any disposition to perpetrate their horrid crimes? Did the thief at that time meditate future thefts and villainies? Did the man who was unjust in his commerce and dealings, then scheme and plan future fraud and injustice against his neighbor? Did the misers heart then repose itself on his god?—I mean his gold? Did he then “make gold his hope; and “say unto the fine gold, Thou art my confidence!” Did the profane swearer and blasphemer then ask God to damn either himself or his neighbor? I can hardly believe there was a man amongst us so intemperate, so lewd, so addicted to the hidden things of darkness and dishonesty, so devoted to his mammon, or so profane and impious, as to do thus at the mentioned time. No: how wicked soever some of you might possibly be; yet you all then feared God; or at least were afraid of him, and afraid to sin against him; because you then really believed him to be holy, just and almighty. The drunkard was then far from desiring to indulge to intemperance: The burning adulterer’s blood then ran cold in his veins: The thief would then have dropped the spoil from his hand; and he that stole, resolved to steal no more: The most zealous worshipper of mammon, then wished for a treasure in heaven: And the blasphemer’s oaths and curses, were turned into prayers and supplications. All, all then thought, that God was worthy to be feared, and glorified, to be worshipped and obeyed.

Well: Do you suppose that God is changed; and now become a different Being from what he so lately was, when he shook the earth, and caused the pillars of heaven to tremble? Do you imagine, because you do not now see these same manifestations of his power, justice and holiness, that of almighty he is now become weak! Of just, regardless of justice! Of holy, unholy! And consequently, that though he was lately so proper an object of your fear, yet he is no longer so; but that you may now safely contemn him? That you may trample upon his laws? That you may tread under foot his Son? That you may disregard his word, and profane his day? That you may neglect his worship, his institutions and ordinances, and despise his threatening’s? Can any man be so extravagantly foolish as to think thus! Verily, he is the Lord, and he “changeth not;” the “Father of lights, with whom there is no variableness, neither shadow of turning.” Tho’ the earth should never “tremble” again, he is always the same holy, righteous, powerful and jealous God, which you lately conceived him to be, when he “looked upon it”: He is the same when he dwells in the calm, and all nature smiles around, as when he “makes darkness his secret place,” and “flies upon the wings of the wind;” when he gives his voice in thunder, “a smoke going out of his nostrils, and fire out of his mouth, devouring!”

Take heed, therefore, that you do not suffer those just sentiments concerning the power and holiness of God, and your duty to him, which were lately awakened in you to be effaced; cherish and improve them; and let them be written on your hearts as with a pen of iron, and the point of a diamond; or as graven on the rock for ever. You ought certainly always to fear, always to glorify, always to worship and obey him, who is always almighty, always holy, always just, always present with you; even tho’ he should never manifest himself and his power to you in the same terrible manner. But you are to remember, that God may perhaps visit us with other, and far greater earthquakes, or with terrible and destructive inundations of the sea, as he has lately visited others, in divers places; or with other desolating judgments: For he never wants means and ways by which to punish the disobedient, even in this world. But, as was said before, tho’ his judgments should not now be made manifest in any of these ways; yet he is always the same glorious, righteous, almighty and terrible God; even “yesterday, to day and forever”. And he will most surely render to every man according as his work shall be, in the day that he has appointed for that end, whether it be near or remote. You should therefore have an habitual reverence of him upon your minds; such a one, as thro’ his grace and assistance, will always be productive of obedience and holiness in your lives. “As he which has called you is holy, so be ye holy in all manner of conversation; because it is written, Be ye holy, for I am holy. And if ye call on the Father, who without respect of persons, judgeth according to every mans work, pass the time of your sojourning here in fear. 56

“Happy is the man that feareth alway; but he that hardeneth his heart shall fall into mischief!” 57 Happy, thrice happy are they, who ever religiously reverence, and sincerely obey almighty God; and who are the objects of his peculiar love and favor, thro’ the glorious Mediator of the new covenant. Miserable, beyond expression miserable are they, who are the objects of his righteous displeasure, thro’ sin; thro’ obstinate impenitence and unbelief. What real harm or evil can come nigh he former, shielded by that hand that “garnished the heavens”, and formed “the crooked serpent!’ 58 What good can the latter expect, under his frown, whose “right hand shall teach him terrible things!” 59 What worm can resist omnipotence! What craft can evade the justice of the all-wise and holy One! Or who fly from him who is omnipresent! If you can fly to the most distant parts of the earth or sea, he is there: if you ascend to the highest heaven, behold he is there, if you descend to the lowest hell, he is equally there! And wherever he is, he is always the same glorious almighty, wise and holy Being; the friend, the hope, the salvation of the good; the enemy, the terror, the destruction of the wicked! “When he giveth quietness, who then can make trouble? And when he hideth his face, who then can behold him? Whether it be “done against a nation, or against a man only?” 60 Who then? what man? What nation shall not fear thee, O Lord, and glorify thy name! Shall not all nations come and worship before thee!—

I would willingly hope there may be some good effects of the late terrible earthquake, not only in this capital, where people have appeared to be so generally affected by it; but throughout the province; and indeed throughout these American plantations and colonies, as far at least as it extended. Without running into a common-place invective against the times, or pretending to give a detail of the sins and vices which are prevalent thro’out these British colonies, one may, I think, say with modesty, that there is ample room for, and therefore great need of, a general reformation of manners; even amongst persons of all orders and degrees, without any exception. This alarming occurrence of providence, is, in the nature of it, as a moral means, calculated to produce such an effect, such a reformation. And considering our lives are all thus mercifully preserved, one would willingly believe that God really meant it to us for good, that we might awake to righteousness and not sin; that we might be made partakers of his holiness hereby; and so become the suitable objects of, and in due time enjoy, his favour; that kind protection, and those smiles of his providence, which we at all times need, and, in some respects, more particularly at this.

To mention only one of these respects: We are, and have been for some time engaged in an unhappy, and hitherto, an unprosperous war with our French neighbours on the continent, and their Indian allies, supported and encouraged in their encroachments and depredations by the power of France: With which martial, though perfidious nation, a more general war seems to be now on the point of breaking out. Four 61 (that is, in short, all the late) expeditions made against them, for the securing of our territories, have proved unsuccessful; and not only unsuccessful, but some of them fatal to a considerable number of British subjects; and not only so, but some of them at least, very dishonourable to the British name and arms: Not to say anything of the great expense of these expeditions to the crown, and to these colonies.—How have these colonies lately bled! How are some of them still bleeding, by treacherous and savage hands! What scenes of violence! Of rapine! Of fire! Of murder! Especially on the frontiers of the southern colonies!