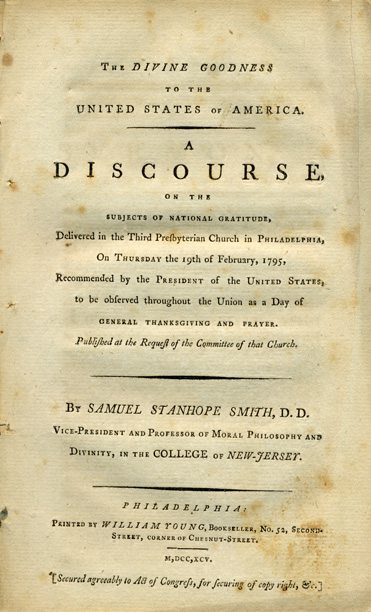

The following is the text of a sermon preached by Samuel Stanhope Smith on February 19, 1795 – the day of the national Thanksgiving proclaimed by President George Washington.

Samuel Stanhope Smith (1751-1819) graduated from Princeton in 1769 and began helping his father (a minister) with his school and studying theology. He became a tutor at Princeton in 1770 where he studied under John Witherspoon and was ordained in 1773. Smith played a role in the founding of August County College (later Washington and Lee Univeristy) and Hampden-Sydney College. He became president of Princeton upon Witherspoon’s death in 1794 and served until 1812.

To the

United States of America.

A

DISCOURSE,

on the

Subjects of National Gratitude.

Delivered in the Third Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia,

On Thursday the19th of February, 1795,

Recommended by the President of the United States,

To be observed throughout the Union as a Day of

General Thanksgiving and Prayer.

Published at the Request of the Committee of that Church.

By Samuel Stanhope Smith, D.D.

Vice-President and Professor of Moral Philosophy and

Divinity, in the College of New-Jersey.

SERMON, & c.

PSALM cvii. 21.

Oh! That men would praise the Lord for his goodness, and for his wonderful works to the children of men!

This verse is the chorus1 of a psalm destined to offer to God the praise of a devout and grateful people for the goodness of his providence towards their nation, and individually towards themselves in various situations of life. It is therefore a proper introduction to our present duty. “Let us sacrifice the sacrifices of thanksgivings, and declare his works with rejoicing.”

Thanksgiving to God for public, or for private blessings is an act of worship as reasonable as it is pious—because, as the whole course of nature is arranged and moved by him, every good and perfect gift, which we enjoy, must flow to us from the immediate direction and beneficence of his providence. Surrounded continually with many proofs of the divine goodness, and partakers of many of its fruits, thanksgiving ought to form a part of our daily devotions. But singular instances of personal or national felicity require public and solemn acknowledgments. Connected by fraternal relations with the whole family of mankind it is our duty to rejoice in their happiness, as well as to sympathize with them in their misfortunes. But, united with our country by more intimate ties, it is especially our duty to bring our vows and offerings of praise for her prosperity before the throne of eternal mercy. To this pious office we are now invited by her voice speaking through that illustrious and excellent magistrate who adds to all his other virtues a sacred regard to religion, and who has ever shown an exemplary and humble acknowledgment of divine providence, even in those moments, so glorious to himself, when the human heart, elated by the splendor of success, is most apt to forget its dependence upon God.

Although it is the business of the philosopher to trace the relations of causes and effects, and though every event in society, as well as in nature, may be referred to some adequate cause incorporated into the system of the universe; yet does not this impair our obligations to God, the first mover of all, or diminish the reasonableness of our present duty. He who created the universe, who gave to all things their respective powers, and arranged their combinations, foresaw also their results, intended every end, and prepared, in the general system, the necessary means to accomplish it. Short-sighted indeed is the man who terminates his view on the means, and who does not discern in them the superior direction of that Infinite Being from whom they have derived their existence and their agency. When therefore I retrace our mercies, however a speculative mind may be able to refer them to political, or to natural causes, it is our duty to direct our gratitude ultimately to the Supreme Disposer of all events, who, in the plan of the universe, had prepared, and in the train of his providence has conducted these causes to a happy issue.

It will be impossible, in the time allotted for a single discourse, to go into a detail of all our public blessings; and I forbear, at present, to point out the chastisements or the threatening of Divine Providence which have been mingled with them, and which should awaken within us an humble and holy circumspection of conduct, and preserve us, in our prosperity, from an undue elation of mind. I shall confine my view to a few of the most obvious and important subjects of national gratitude, that are either peculiar to the time, or have been suggested by some striking circumstances in the conduct and opinions of the present age.

The subjects then to which I shall call your attention, at present, and on which I would awaken your gratitude are, the existence and success of the federal government—the continuance of peace with the powers of Europe, and the prospect of returning peace with our savage neighbors—our internal tranquility, and particularly the suppression of the late unhappy insurrection.—And lastly, that which, in the enumeration of national blessings, ought always to hold the chief rank, our enjoyment of the Christian religion I nits purity, unshackled by power, uncorrupted by fraud.

I. In the first place the existence and success of the federal government.

Altho’ this system was framed by men of acknowledged patriotism, and distinguished talents; yet, as it is so difficult in theory to embrace and reconcile the infinite diversity of interests and opinions that exist in an extensive country, to seize the proper springs of human action, and, by a single impulse, to move ten thousand wheels, the forces and tendencies of which are hardly subject to calculation, and as in operation every political theory is liable to be deranged by unforeseen accidents, government, at first is a measure merely of experiment. It requires time to verify, or to correct its principles. These observations justify me in going so far back as the establishment of the federal government, and calling it up at present as a subject of acknowledgement to heaven. The experience of six years entitles us now to call it a blessing. It has more than realized the expectations of every friend to public order who wished to see energy infused into the laws, of every real patriot who hoped to see public credit redeemed, and the prosperity of the nation established on a firm basis, and even of every enthusiast for his country who fondly gloried in the name of an American. Under the former system, the exertions of the states were divided, unequal, dilatory, and feeble. No common principle of union and energy pervaded them, and concentrated the efforts of the whole. The supreme council of the republic, divested of power, could only recommend their duty to the citizens, and supplicate from them their tardy, their jealous, their parsimonious, and reluctant aids. America resembled a giant paralyzed, and laid upon his back, who can move but one limb at a time, and that feebly and irregularly, and who, robbed of his strength, can use his hands only to beg a precarious assistance of his children.

Public credit was expiring—general industry languished—the resources of the nation were inactive and unexplored—the soldier was defrauded of the dear bought reward of his dangers, and his toils—the faithful patriot who had sacrificed his possessions to the liberty of his country was oppressed with want—and foreigners who, through admiration of our heroism, had been led to trust our in integrity, were beginning to turn their admiration into contempt. That proud and irritated nation whose setters we had broken, triumphed us in our extremity complained of our injustice—and the adherents of monarchy laughed at the imbecility and faithlessness of the people.

It has frequently been asked, whence it could arise that men who had acquired so high and just a reputation as those patriots had who conducted our revolution, should frame a system of government that on experience has been found so inefficient and injurious? Illustrious men! I venerate their memory—But they were deceived by that noble enthusiasm which they felt in their own souls, they were deceived by that elevated and sublime virtue which was displayed at that time by the whole mass of the people. Advice was law—the public will anticipated the resolutions of the legislature—every citizen contended who should serve his country best, and who should make to it the most illustrious sacrifices. Those great legislators forgot that this was only a revolutionary virtue—they forgot that it is the character of great and generous passions to draw every other principle to their service, and to elevate human nature to their own dignity. In the transport of liberty they fondly hoped that it was the virtue, not of the occasion, but of the people—that it was peculiar to their country—and that, when she should be emancipated it would be eternal. They framed therefore a system of government adapted only to patriots, and heroes,—a government, that did not contemplate those unjust, and selfish principles which take possession of the human heart in the ordinary state of society, and which cannot be made to bend to the public good but by the force of the laws, hence resulted the imbecility of our former federation, and the numerous evils that were growing upon us apace under a system that was chiefly advisory, and that had not within itself the efficient springs of action, nor the power of compulsion—But let us remark the change that has taken place, and with gratitude to heaven let us remark it, since the new system has been established.

The first benefit that has accrued, and that is, indeed, the foundation of almost all others, is the resurrection of public and individual credit. Confidence in the laws, and confidence among the citizens has been restored; millions that were lying dead in the hands of the possessors, were suddenly revivified, and brought into active, and extensive operation. What has been the consequence? A face of prosperity was instantly diffused over the whole continent. Instead of that torpor that benumbed the hands of industry, enterprise was reanimated—agriculture began to flourish—commerce was extended—the extremities of the globe were explored by our merchants—and India and China saw with astonishment in their ports the ensigns of a new nation which seemed to have suddenly sprung out of the earth. Improvements are rapidly extending themselves. Roads of communication are stretched in every direction—canals are opened—rivers are united—the forests are extirpated—the earth subdued under the active toils of the husbandman, yields a double increase to his vows. The arts have been reproduced—new ones have been created—the limit of cities have been enlarged—new ones have been built—labor and industry are everywhere renovating the face of nature. Were all the improvements of a few years within the United States collected together so that they could be contemplated under one view, how would they beggar the utmost efforts of despotism? Despots, like the Roman emperor, or the Russian czar, may drain their empire to raise by force one splendid capital encompassed by deserts, and by inactive and disconsolate vassals—liberty can rear a thousand flourishing cities, everywhere filled with happy and industrious citizens, surrounded by fertile and cultivated fields. She diffuses population and strength, improvement and wealth throughout the whole republic. The empire of the despots is like the monstrous image of Nebuchadnezzar, the head of which was of gold, but it was supported by legs and feet only of iron and clay. The republic resembles the Jupiter of Phidias, where you behold gold and ivory, majesty and beauty, proportion and symmetry in every part. What thankfulness do we owe to God, whose providence presides over all, for the liberty which we enjoy. And, when we compare our present situation and prospects, with the desolations of the late cruel war waged upon us by tyrants, or with that state of imbecility and languor which afterwards succeeded under a puny and paralytic government, what praise is due to him for the blessings of our present state? You now see the laws active and revered—the tribunals enlightened and impartial—the republic respected, her friendship courted, her wisdom admired by all nations, and her example copied by one of the most powerful upon earth—Would to heaven, that that great and heroic people had copied also a larger portion of her moderation!

This government contains an admirable balance of liberty, and of energy. Resting on the free election of the people in all it departments, and supported only by their attachment, there results the highest security that their happiness will be cherished, and their rights protected. But as a single republic is not calculated to act with promptness and vigor over an extensive territory, this defect is remedied by the union of many distinct and sovereign states in one political system. Each state is calculated to maintain and promote the interest and felicity of its own citizens—the general government protects and defends the whole. The general government protects and defends the whole. The general government, like the heart, diffuses the vital principle through every member. But if it acted alone, this current, would flow with a languid motion to the remoter parts, the respective states, like the vigorous muscles of an athletic body, assist to propel it, with warmth and force, to the most distant extremities.

Happy under this admired frame of policy, the principal evils against which we have to guard are those of consolidation, and those of division. Consolidation would end in tyranny—and division would expose to destructive and perpetual wars. To the former of these evils, we are perhaps less exposed than to the latter. The influence, the interests, the vigilance, and, I may say, the pride of the individual states, are our security against it. Division is a calamity which we have more reason to fear. And I see, with infinite regret, that obstinate factions are beginning to be formed. To what degree they may proceed in decomposing and dissolving the present harmonious system van be known only to God, and to posterity. But, next to slavery, I deprecate its dissolution as the worst of evils. If we would effectually guard against it, we ought to be no less cautious of weakening the federal government, than vigilant against the insidious approaches of tyranny. On this subject the Amphictyonic confederacy in Greece affords us an instructive example. The jealousy of the states which composed that league, gradually detracted from its authority, till at length it was deprived of the power necessary for the general interest. Ambitious demagogues, that they might acquire influence at home, impelled the people to resist its decrees. The council of Amphyctions was at length dissolved by the contempt into which its authority had fallen It was reunited only on particular emergencies by some common and imminent danger that threatened Greece. Then you might see it a theatre of rash and hasty treaties, made and observed with Macedonian faith. Cemented for a moment by fear or by interest, they were always broken by caprice or by intrigue. The states which composed it were engaged in perpetual wars; and, finally, it became the tool of a tyrant by whom they were successively enslaved. Such, also, are the unhappy consequences which I anticipate from dissolution of our union. We shall become the prey of one another, the sport of sovereign intrigue, and at last, perhaps, the victims of foreign ambition.

When we contemplate these dangers, with what ardent gratitude should we raise our hearts to the throne of the Eternal for our present tranquility and union? With what fervor ought we to address our prayers to him, to the control of whole providence all events are subject, that he would graciously preserve to us these inestimable blessings—that he would eradicate the seeds of faction wherever they are beginning to shoot—that he would endue our councils with wisdom, and with moderation—and that he would continue to a remote posterity that happy federation under the influence of which we have already begun to enjoy such an unusual series of public and private felicity?

When we recollect the difficulties that attended the organization of this government by the convention, and its reception by the states, we are led more particularly to recognize in it the direction and good providence of God. The jarring interests that were to be compromised—the jealousies that were to be allayed, or satisfied—the pride that was to be reconciled—the powers vested in the government—the right and extent of taxation—the establishment of the executive—the organization of the judiciary—the constitution of legislative so as to give an equal representation of the people, and yet secure the sovereignty of the states.—These, and innumerable other difficulties which cannot here be detailed, but which would necessarily arise in arranging such a vast and complicated system, long held the convention in balance.—They were ready to abandon their work in despair, when, suddenly, a luminous wisdom disembroiled their embarrassment, a spirit of conciliation compromised all interests and opinions. Shall I not justly ascribe this happy issue to the mercy and direction of heaven? For, although the philosopher and politician may be able to develop the causes that conspired to produce the event, yet, are not the springs of all causes in God? Does not he hold in his hand their eternal chain and guide, by an invisible energy and wisdom, their infinite relations and results? Among the favorable circumstances accompanying the establishment of the federal system, I cannot omit to mention the preservation of the life of the worthiest of our citizens, and his acceptance of the chief magistracy, to whom America had before owed so many obligations, and who has, in so uncommon a degree, united in his favor the public sentiment and suffrage. His acknowledged talents, his disinterested patriotism, and his eminent services to his country, gave weight to his opinion in the public councils, contributed, in no small degree, to the adoption of the constitution, and have greatly promoted the stability, the tranquility, and the energy of its operation.—The goodness of God in his providence over nations, often appears in the characters which he prepares for their safety and defense. David he raised up for the glory, Cyrus he anointed for the restoration of his ancient, and chosen people. I confess, I recognize in this illustrious citizen the immediate hand of heaven. Hardly can I imagine talents more fitted to our situation, both in war, and in peace, than those which distinguish and adorn his character. Do I depreciate, by this merited eulogy, the talents of his fellow-citizens?—No—but where have we seen such a fortunate assemblage of caution and intrepidity, of patience and enterprise, of modesty and firmness, of cool and penetrating judgment, and prompt decision, of love of the people, yet superiority to popular clamor, and finally of that felicity which the Romans so much valued in a general—a Christian will call it the smiles of divine providence that seems to render auspicious all his undertakings?—Will envy dash back these honest praises in our face, by saying that other citizens might have been found of equal talents? Be it so.—But they have not been found. What though Rome might have possessed other senators besides Fabius who could have vanquished Hannibal? Or besides Fabricius who could have disdained the bribes of Pyrrhus? Shall Fabius or Fabricius therefore be robbed of the glory with which they have been crowned by the consent of ages?—I esteem it one of our chief mercies, and I count it one of the noblest acts of patriotism in him to forsake his secure situation on the summit of fame, to accept the dubious helm of government, and, for the good of his country, to put to risk a reputation which history assured to him, untarnished and immortal.

II. Another cause for which we are this day called to render praise to almighty God is the continuance of peace with the powers of Europe, and the prospect of its speedy re-establishment with those savage tribes who have so long harassed us with their depredations.

Peace is an inestimable blessing to a young and growing country not yet enervated by luxury, nor sunk into effeminacy and sloth. These vices indeed sometimes require the purifying flame of war to purge them off; and the state emerges from its fires regenerated, as it were, and new-created. But we need tranquility in order to repair the losses which we incurred in effecting the revolution. We need it to relieve the people from that load of debt which was the price of our freedom. We need it to augment our population, to cultivate an immense scope of unimproved territory, to promote our commerce, to cherish the arts, and to hasten the progress of society and manners towards perfection.2 War, in our present situation, particularly with Europe, would be to us one of the most fatal calamities. Not to speak of the evil of an accumulated national debt that oppresses the people that overloads the springs of government, that cheeks public enterprise and improvement, and must necessarily long hold a young country in a state of infancy and depression. Our own remembrance of the miseries of the late war with Britain will teach us to estimate its evils in the desolation of our cities—in the conflagrations and rapine that spread distress throughout the United States—in the loss of our friends and fellow-citizens by battle, captivity, imprisonment, and contagion. O Britain! Thy prison-ships, those vaults of contagion, those dungeons of infernal cruelty and torture, the eternal reproach of thy humanity, still fill our souls with horror at the recollection. These cruelties that robbed us of our brothers, affect us infinitely less for their loss than for the manner of their death.—It is the manner of savage warfare likewise, which, though less pernicious to the republic at large, renders it peculiarly dreadful to individuals who lie exposed to their inroads. The continual uncertainty of death from an enemy who seeks his prey by stealth, the indiscriminate murder of each sex and of every age, the atrocious barbarity with which they sacrifice their victims, and the fiend-like cruelty with which they inflict and enjoy the torments of the sufferers, while they should make us at all times fervently deprecate an Indian war, ought now to increase the sincerity and ardor with which we return our thanks to Almighty God for our present prospects of peace.

He has humbled us before them in successive defeats. He has permitted them to spread devastation and blood over a frontier of a thousand miles. He has made them the rod by which he has chastised us. Yet may he say to us as to his ancient people, “For a small moment have I forsaken thee, but with great mercies will I gather thee.” Lately, he has turned our defeats into victory; and the humbled savage, abandoned by that unfriendly power which had inflamed his animosities, supplied his arms, and directed his operations, begins to turn his thoughts on peace.

But, as I have suggested, it is a still greater mercy, that we have been preserved from being sucked into the gulf of European politics and wars. We are so involved by commercial relations with the system of Europe, that we are necessarily affected by their quarrels, and are in no small danger of being sometimes obliged to take part in them. It is but lately that we have been reduced to a most delicate and hazardous crisis by the haughtiness and violence of one nation, and by the audacious attempts of the minister of another.3 Has not the former, affecting a tyranny, and dictating a new law of nations upon the ocean, committed the most injurious and insolent spoil upon our commerce? Has she not treated our citizens with every outrage that could flow from hatred and contempt? Has she not held fortifications? has she not known to have excited that ferocious war that has so long afflicted our frontier—to have kindled against us the rage, assisted the councils, and concentrated the force of the savage tribes? Is it not plain, that she meditated hostilities? That she had already conceived the purpose of attacking us, and only waited the opportunity to carry it into execution? What her violence could not do had been almost affected by the artifices of a bold and insolent minister. Contrary to the rights of our sovereignty and the obligations of our neutrality, he equipped hostile armaments in our ports—He arrayed our citizens under the banners of his nation—He endeavored to incite the people to rebellion against their own government.—In projects so daring and atrocious he was supported by a party in the republic, not inconsiderable in numbers and influence, who attempted, in the pursuit of their favorite design, to brave all the constituted authorities of their country, and who were clamorous for war. Different motives seem to have actuated this party. Some were, and others affected to be, influenced by mistaken gratitude to a nation struggling for its liberties which had rendered us the most necessary and efficient aids, while we were contending for the same glorious object.4 Some, I fear, were governed by a deplorable ambition which hoped to mount into notice and distinction only by the confusion and miseries of their country.—Others, fired by a generous indignation against that government from which we have received so many injuries, were willing to retaliate its insolence and crimes.—But, shall we, in pursuing either reparation or revenge, inflict tenfold injuries on our own country? It is lawful, say they, it is laudable to detest, and to nurse in the hearts of our children, a military rage against a nation that has been willing to destroy us, and that still harbors against us the most hostile resentments. This maxim, my brethren, is contrary to the spirit of our holy religion. But, religion apart—be it as they will—let every American have been led by his father, like Hannibal, to the altar, to swear eternal hatred against the enemy of his country—should he not, like Hannibal, wait the proper moment to avenge her wrongs? Should he not at least be compelled by necessity alone to wage a disadvantageous war?

The causes I have mentioned seemed to be impetuously urging us to a desperate crisis when the goodness of heaven interposed to arrest the danger. For shall I not ascribe to the secret inspiration and direction of the Most High, the wisdom and moderation of the councils of America? Shall I not ascribe it to a merciful providence over us that the hostile plans of Britain have been all blasted on the plains of Belgium? Do we not owe to the mercy of God the prudence and firmness displayed, in the most embarrassing circumstances, by that great magistrate who presides at the head of our government. I see him like a rock in the mist of the ocean, receive unshaken the fury of all its waves. Violence, intrigue, faction, dash themselves to pieces against him and fall in empty murmurs at his feet.

Let us render praise to the Eternal who, in the midst of these imminent dangers, hath hitherto preserved to us the precious blessing of peace with the nations of Europe—who hath lately subdued our savage enemies under the arms of a general who has deserved well of his country—and who, in his good providence, hath in every exigency, raised up for us the natural means of safety and defense. “Salvation belongeth unto the Lord! They blessing is upon thy people.” Psalm, 3, 8.

III. Another subject of thankfulness on this day, is the preservation of our domestic tranquility, and particularly the extinction of a dangerous insurrection that put in hazard the happiness and safety of the republic.

We cannot be sufficiently grateful to heaven for the blessings of internal harmony and order. We cannot be too careful to preserve them inviolate. When civil discord agitates a nation, all the ends for which men united in society are defeated. And in civil wars, a rage more ardent and destructive is commonly excited than that which takes place in hostilities between independent nations. We have reason to bless God that, amidst all the subjects of dissention and party that exist among us, our peace at home remains present so entire. That formidable insurrection, which threatened the existence of government, or the dismemberment of the republic, has been crushed under the powerful arm of the law. The energy of the measures that have been adopted, and the alacrity of the citizens in proffering their services to suppress rebellion, and to testify their attachment to the constitution which they had chosen, have, I hope, effectually repressed that spirit of anarchy and disorganization that was beginning to spread itself with alarming rapidity. The rebels relied for protection and support on the favor and concurrence of a large part of their fellow-citizens, and on the indifference and connivance of the rest. Good God! What would have been our deplorable condition if their ideas had been realized? Divided, discontented, powerless—the contempt and insult of foreigners—the sport of their intrigue—severed to pieces—attacked by piece-meal—distributed among them, we should have been without a name, without a country, without liberty. What is liberty but obedience to the laws? Where the laws are disobeyed, no man can be secure—no man can be free. In what light then are we to view the ringleaders of this insurrection? In what light are we to view those who assisted and fomented it? Are they not incendiaries? Are they not parricides? Do they not deserve the detestation of every good citizen?

Too many, I fear, have been indirectly accessory to this unhappy event who intended not to all the consequences that have resulted from their opposition to government. But the phantoms of tyranny that were perpetually conjured up—the violent and unwary appeals that were made through the channels of the press, and by subservient orators to the passions of an undiscerning multitude who were remote from the sources of real and authentic information—the advantage taken of these by artful and ambitious demagogues who hope to produce themselves to notice, and raise themselves to eminence by playing on the credulity and follies of the people, all contributed to urge the opposition of the insurgents to a crisis—at last their frenzy burst through every tie of duty and subordination, and they dared openly and triumphantly to trample on the laws. Ah! The passions of a people are dangerous engines of faction or ambition. Often you may rouse them to a destructive fury by the grimace of false patriotism, or the fanaticism of mistaken liberty. But you cannot mark the point beyond which they shall not rise. They are not to be allayed by the same arts of persuasion by which they were excited. When they have mounted to a certain pitch, if they are not subdued by the force of the state, they subside only after having spent themselves in acts of violence and horror—they come to be shocked at a review of their own works. Republics, though more calculated for the improvement and perfection of human nature than other forms of government, are peculiarly liable to be disturbed by the arts of demagogues—and demagogues are the greatest curse of republics. May Americans return to their own moderation and good sense. Let no combination of men attempt to resist the will of the majority constitutionally expressed. Abhor the factions that lead to embroil the public peace. Cherish internal order as being among the most precious gifts of Heaven. And let us return thanks to God who hath “stilled the tumults of the people,”—who “hath caused the crafty to be taken in their own snare”—who hath made the counsel of the forward to be carried headlong.”

IV. The last subject of national gratitude which I have mentioned, is our enjoyment of the Christian religion, freed from the setters both of civil and ecclesiastical power.

The Gospel of Christ is the most precious gift which God hath bestowed upon mankind. Without it, this world would be a gloomy vault in which we should wander blind, or only engaged in the pursuit of unreal phantoms—a miserable prison in which we should groan a few days and be no more. Human reason had for ages sought in vain for a clear and simple law of duty that should be intelligible to all, and by its certainty possess sufficient authority to impose its obligation on the conscience. In vain it endeavored to penetrate the veil with which God hath covered the mysteries of futurity—It met with nothing in its researches but eternal disappointment—a dismal uncertainty still rested upon death. And the miseries of life pressed the heavier upon mortals, that they had no solid hopes of a future and better existence. Christ hath revealed a law of duty so perfect, that reason though compelled to approve could never have reached it—so simple that the humblest understanding can conceive it—and possessing such evidence and authority as to give it the firmest hold upon the heart. Chasing from the human mind the frivolous, or the gloomy superstitions with which it had been filled, the gospel imparts to it the most sublime discoveries of the divine nature—Raising it to a pure and rational piety towards the Father of the universe, it becomes to it the source of the sincerest and the noblest pleasures. But it displays its excellence and power chiefly on two subjects on which reason has been always most embarrassed, and on which it has drawn its dubious conclusions with the greatest diffidence, the forgiveness of sins and an immortal existence. It offers to the penitent the only solid ground of peace of conscience by revealing the atonement, and by assuring him of the promises of divine mercy. To the pious, it confers on life its highest enjoyment, by the hope of living forever; and its calamities it alleviates by enabling them to look forward to the period, not far remote when “God shall wipe away all tears from their eyes; and there shall be no more death, neither sorrow nor crying; neither shall there be any more pain: for the former things are passed away.” Rev. xxi, 4.—Precious! Ineffable consolation under all the anxieties and sorrows that prey upon the human heart, and that, without this, would often make us weary of being!

The blessings which we enjoy from religion as individuals, deserve our recollection and acknowledgment on a day of national thanksgiving—because the nation is but the mass of individuals. But it has more direct political relations which require us to recognize it as the chief of our public mercies.

It is the surest basis of virtue and good morals, without which Free states soon cease to exist. Even the superstitious rites of paganism, by acknowledging a deity, were infinitely preferable to absolute infidelity. Enforcing the dictates of conscience by the dread of a divine power, they added an important sanction to the moral law.5 Much more is a religion of principle, like that of Christianity, calculated to regulate the manners of men, and to produce the most happy effects on society. Taught from their infancy to do justice, to love mercy, and to respect the laws of their country as the ordinance of God, they are prepared to become good citizens. Impressed with the fear of a holy and eternal power that takes cognizance of human actions—directed continually to that righteous tribunal where virtue will meet with the most illustrious rewards, and vice shall suffer its deserved punishments—instructed to believe that God regardeth the heart, the principle and fountain of conduct, can they enjoy stronger motives to purity of life? Or can human wisdom impose on immortality and disorder more effectual restraints?

This holy religion we enjoy, freed from the degenerating influence of civil, or of ecclesiastical domination. They corrupt in the church whatever they touch. Among us truth is left to propagate itself by its native evidence and beauty. Stripped of those meretricious charms that, under the splendor of an establishment, intoxicate the senses, it possesses only those modest and simple beauties that touch the heart. It recommends itself by the utility of its effects. Wealth and power are apt to inflame the pride, and softer the indolence of the priesthood, in whose hands religion then degenerates into a lifeless form, or into a frivolous system of foppery and superstition. But in America, a diligent and faithful clergy resting on the affections, and supported by the zeal of a free people, can secure their favor only in proportion to their useful services. A fair and generous competition among the different denominations of Christians, while it does not extinguish their mutual charity,6 promotes an emulation that will have a beneficial influence on the public morals.

The lawgivers of antiquity convinced that virtue is essential to the prosperity, and even to the existence of free governments, and finding in their religions only ceremonies instead of precepts, were often obliged, order to supply the defect, to have recourse to an austere and rigorous discipline of labor and obedience, that they might prepare their youth to become citizens. To these they added inspectors of the public manners,7 whose duty it should be to preserve them from degenerating, or to bring them back to their original standard. These advantages, sought so earnestly by the greatest efforts of legislative genius among the ancients, are all happily procured to us by the Christian religion. Her instructions take possession of the heart from our most tender years—She forms the morals of the citizens under the sacred authority and care of the church—She teaches the purest system of virtue that was ever taught on earth—She adds to virtue the most powerful sanctions that were ever known among men. And what those legislators with difficulty and but partially accomplished by their censors of the public manners, she more effectually attains by the moral discipline, and the useful emulation of the different sects.

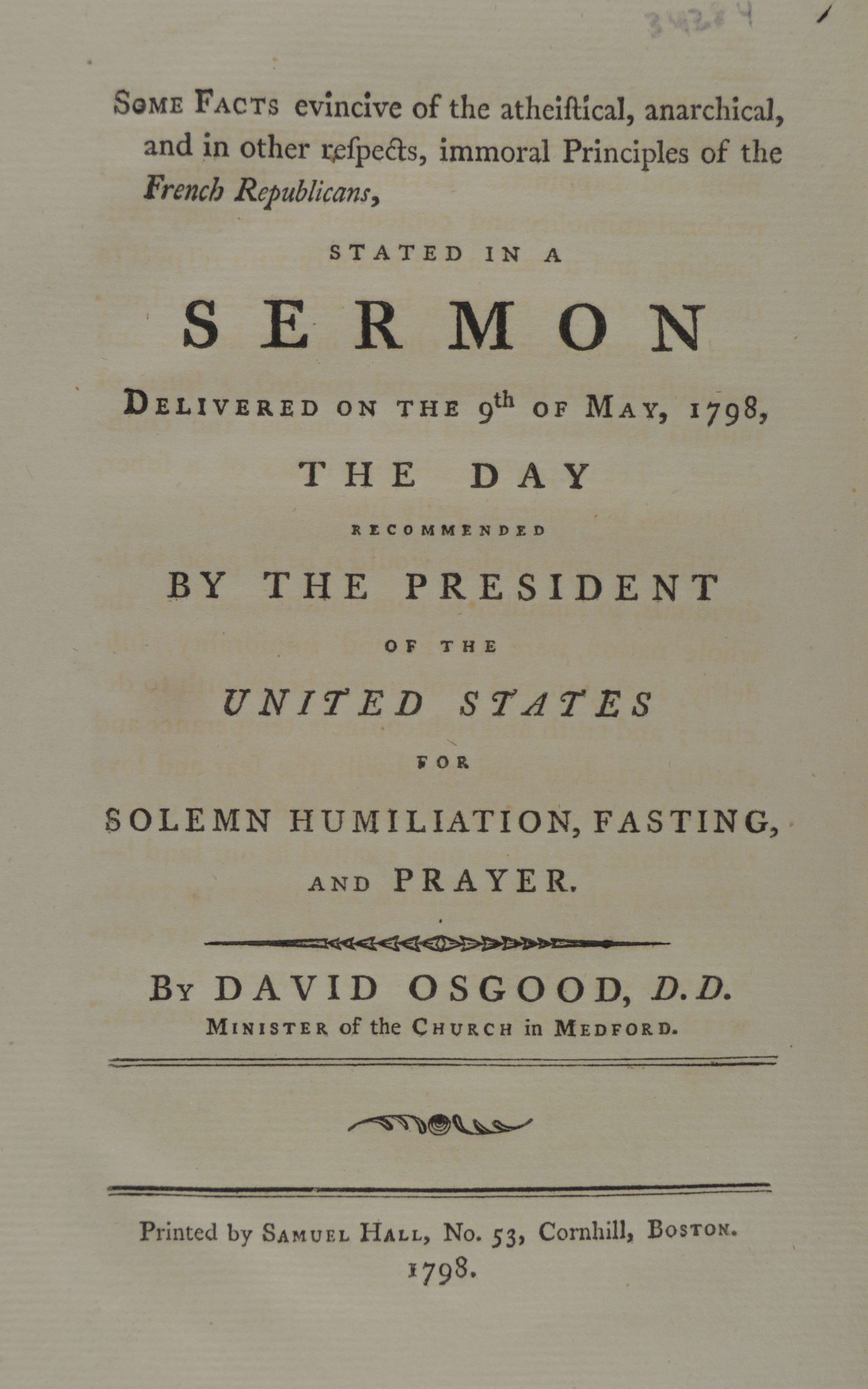

Lately, there has sprung up a sect of political emperies who pretend to deny the necessity or utility of religion, and who would willingly discard it from the state, as they have eradicated it from their hearts. They system of infidelity which was once thought to be cold and gloomy, has at length shown itself to be furious and inflamed. In one nation, where it could act out its spirit, we have seen the apostles of atheism more fanatical than the disciples of Omar, who endeavored to destroy all the monuments of art and genius, and more bloody than the votaries of Moloch who worshipped their infernal idol in the blood of men. Blaspheming the living and eternal God, have they not consecrated to a false and misguided reason with hecatombs of human victims? I may now speak freely on this subject. Those of my humble and imitative countrymen who adopt their opinions implicitly from this nation, and who so flexibly bend after every revolution of party in its capital, will not now deem it profane to un-nitche Danton, Brissot, and Robertspierre, or to drag Marat form his pretended godship in the pantheon where madness and folly had placed him. These men disdaining the examples of other ages, and mad with rage against religion, endeavored to extirpate it from the republic. The more effectually to insult its worship, they instituted a farce in the temple of reason. Was it God, the eternal reason, who framed the universe, whom they meant to adore under a new title? No—God did not form a part of their system—The people were not able to comprehend so multiform and abstracted an idea. But, filled with admiration of their own wisdom, it was this which they canonized in their heated imaginations.8 Each man carried his ridiculous deity in his own brain. ‘Twas its visions and whimsies that he deified—O Egypt! The scorn of ages for the contemptible worship of reptiles and monsters! Did thy temples ever contain so many monsters, such fantastic and reproachful mockeries of divinity, as did these strange temples of reason!

Blessed Savior! Are these the substitutes which infidelity invents for the purity and glory of thy holy religion? Are these the works of those strong and superior minds who affect to despise thy humble birth; thy innocent and instructive life! The condescension of thy mercy! The sacrifice of thy cross! The hopes of immortality which thou hast revealed, and which thou hast verified by thy resurrection! The errors of the human imagination, when it departs from thee, are among the strongest proofs of the truth and excellence of thy gospel!—Ever, may we cherish it as the dearest, the most sacred treasure that heaven has conferred on mortals!

But, could these pretended philosophers, these novel politicians, succeed in their attempts to eradicate the principles of religion from the minds of men, what would be the consequence on the conduct of life, and the order and happiness of society? The general mass of mankind can never be made to embrace the principles of a sound and extensive morality by the evidence of reason alone.—Their minds are too limited—Their occupations are too numerous.—They must receive them from authority.—And no authority is so competent to this end as that or religion. Can their passions be restrained by the delicate force of taste, of sentiment, of honor? No—they must be subjected to the power and control of a supreme legislator who is able to punish and reward.9 —If then, you remove the precepts and sanctions of religion, what limit can you prescribe to the passions of the multitude? What will restrain them from hastening whithersoever pleasure invites, whithersoever want stimulates, or revenge impels? Lust, riot, debauchery; theft, robbery, oppression; treachery, poisoning, assassination would be the fruits of a general atheism. Do these politicians rely upon the power of conscience to control the vicious tendencies of human nature?—Conscience derives its force chiefly from a future state, and from presenting to the mind the power and justice of God. Remove these ideas, and feeble, indeed, in the mass of the people, would be its remonstrances against the temptations of interest, the influence of example, the force of the passions. Without religion the whole fabric of public morals, and of social order, would tumble to pieces. But, thanks be to God! He has implanted the religious principle so deeply in the human heart, that it is impossible for impious politicians ever to eradicate it. The storms of a revolution, or the violence of an atheistic and fanatical10 faction, may shake it for a moment, but afterwards, it will strike its roots deeper, and grow with more vigor and luxuriance. And, I doubt not, that nation is yet destined to be the theatre of a pure, and enlightened piety.

Let us render to God the sacrifices of thanksgiving because we enjoy the institutions and the gospel of Jesus Christ, and enjoy them in so much simplicity, and so much purity. We enjoy the law of truth and holiness revealed by him from heaven—the promise of the forgiveness of sins, and mercy from God to the guilty who are penitent—and the assured hope of life and immortality, which he alone hath brought to light. For a single theorem in geometry did an ancient philosopher, in the rapture of discovery, offer an hundred victims to the deity who had illuminated his mind—what sacrifice shall we pay to God for truths the most glorious and consolatory that have ever been made known to the world? Shall we bring him thousands of rams, or ten-thousands of rivers of oil? No—these would be a poor offering—and God, in pity to our poverty, condescends to accept our gratitude and praise in the room of all. “He that offereth praise, saith he, “glorifieth me.” Let us join in the song of the angels who announced the birth of the Savior.—“Glory to God in the highest! And on earth, peace and good will to men!” Let us re-echo in the church the ascriptions and the triumphs of heaven—Halleluiah!—Salvation, and glory, and honor, and power unto the Lord our God!

AMEN!

Endnotes

1 The whole psalm is constructed agreeably to the rules of that species of poetry by strophe and antistrophe of which we find so many examples, not only in this book, but in other parts of the ancient scripture, and which, from the manner of conducting their music in the public worship, became the prevalent character of the Hebrew poetry. Their musicians seem to have been generally divided into two bands. One band began with a strophe containing some devout sentiment—the other made its responses by an antistrophe which was constructed in different ways; but, most frequently, it contained some contrast or antithesis to the strophe, or introduced some similar and related sentiment, or even repeated the same sentiments with some variation in the expression—an example of which we have in the verse immediately following the text,—“Let them sacrifice the sacrifices of thanksgiving and declare his works with rejoicing.” The former part of this verse was probably played and sung by the first band,—the latter part seems to be the response of the second band. Frequently there was added a chorus, which was either done by introducing a separate band, or by both uniting in the music at the same time. The structure of this part seems to be different in different psalms. In general, perhaps, it was not constructed with that artificial antithesis or reduplication, that prevailed in the rest of the composition. The chorus of the psalm from which the text is taken, and of several others, is a sentiment that appears to contain the burden of the song, and is frequently repeated in the course of the psalm.

Nothing can be more contemptible than the criticism of Thomas Paine on the subject of Jewish poetry, in that book of his which he has chosen to entitle, the Age of Reason; a book more fraught with errors on the subject both of religion and of ancient literature than any of the same size with which I am acquainted in the English language. He has read somewhere, or some person has told him, that many parts of the Hebrew scriptures are written in verse; for of this he could know nothing from his own acquaintance with the original language, or even with the English translation, which he glories either to never have been read, or forgotten. Yet he attempts to prove from one passage in the translation, which he quotes wrong, that, because there are ten syllables together which fall into regular feet, according to the rules of English versification, therefore, the original must have been in Hebrew metre. This is a species of criticism which no man who was not consummate in impudence as well as in ignorance, could have attempted to palm on the public. Whoever thought before him, that a literal translation of verse in one language would fall into verse, of a totally different measure, in another? The ten syllables which he produces are from the first verse of the prophecy of Isaiah–,”Hear O ye heavens, and give ear O Earth”—If he had read his bible, he would have written it with nine syllables, “Hear O heavens, and give ear O Earth.” But to demonstrate that it will make a part of a good English complete, he adds a verse of his own, “Tis God himself who calls attention forth.” By the same rule of criticism, I can prove that Thomas wrote his book in verse. For, for if you take the next eight syllables of his prose, and add eight more, of at least as good poetry as his own, you will have the following lyric couplet.

“Another instance I shall quote,”

Religion’s odious to a sot.

Now this is a proof of the same kind with his, that Thomas Paine wrote in verse. It is probable, indeed as I have said, that a great part of the Hebrew scriptures is written in some kind of poetic measure or rhythm. Critics however are not able to determine whether their poetry consisted in certain combinations of long with short, or of accented with grave syllables, or not; because the pronunciation of the language is totally lost. The most judicious are inclined to think, that it consisted rather in certain contrasts or resemblances that took place between the ideas or objects in different lines, together with a similar structure of period in each. See Lowth de suc. Poes. Heb. Praelec. & prelim. Dissert. To translation of Isaiah.

2 I say hasten the progress of society and manners towards perfection – for, I am not one of those who think rudeness and ignorance essentially connected with virtue.

3 On this subject, when I freely censure the measures of two nations which are invidiously [in a manner arousing resentment] said to govern our political parties, if it be asked to which I attach myself, I say, to neither, but to the people of America.

4 But not to mention that those to whom we were most directly indebted have all been obliged to flee their country, or has passed under the guillotine, they seem to have forgotten that these aids were the result, not of national friendship, but of national interest, and that the claims of gratitude therefore, extend no farther than is equally consistent with our own interest.

5 The legislators of antiquity constantly incorporated religion into their political systems. Xenophon, who was equally an accomplished general, and able statesman, and an elegant writer, always joins the fear of the Gods with the prosperity of states, and makes it one of the chief virtues of his favorite hero.

6 Uncharitable contentious usually spring from the exclusive possession of emoluments and privileges by one party.

7 Such as the Areopagus [earliest aristocratic council which met at the “Ares’ Hill” near the Acropolis] at Athens, the senate and the old men of Sparta, and the censors at Rome.

8 These men rejecting revealed religion and substituting reason in its place, it must have been that reason which each votary possessed, that framed the character of the object of his worship. It must have partaken, therefore, of all the variety and extravagance which the ignorance or fanaticism of myriads of people could give it.

9 It is sometimes said to be improper to sound piety and virtue on the principles of hope and fear in man – – particularly on fear. It is true that virtue, in its perfection is the love of our duty. But its spirit and its habits, must in the beginning, and especially in gross minds, be cultivated by the motives that I have mentioned.

10 We have lately seen that these two characters are not inconsistent as was once supposed. – – And the fanaticism of an atheist is found to be more furious, cruel, and bloody than that of a false religionist.

The Rev. Nathan Strong (1748-1816) was born in Connecticut. He attended Yale, graduating in 1769 (he went on to receive a D.D. degree from Princeton in 1801). Rev. Strong was set in as pastor of the First Church of Hartford in 1774. Interestingly, both his father, also named Nathan, and brother, Joseph, were clergymen as well. Strong became a chaplain in the patriot army during the American Revolution, and was a strong supporter of the American cause. He later was a chief founder and a manager of the Connecticut Missionary Society (founded in 1798), and was involved in the ” Connecticut Evangelical Magazine,” which lasted fifteen years. In this “execution sermon,” preached before Richard Doane was executed for the murder of Daniel M’Iver, Rev. Strong reminds his listeners (including Doane) of the terrible consequences of a sinful life apart from God, and urges them to be reconciled to God through Christ.

The Rev. Nathan Strong (1748-1816) was born in Connecticut. He attended Yale, graduating in 1769 (he went on to receive a D.D. degree from Princeton in 1801). Rev. Strong was set in as pastor of the First Church of Hartford in 1774. Interestingly, both his father, also named Nathan, and brother, Joseph, were clergymen as well. Strong became a chaplain in the patriot army during the American Revolution, and was a strong supporter of the American cause. He later was a chief founder and a manager of the Connecticut Missionary Society (founded in 1798), and was involved in the ” Connecticut Evangelical Magazine,” which lasted fifteen years. In this “execution sermon,” preached before Richard Doane was executed for the murder of Daniel M’Iver, Rev. Strong reminds his listeners (including Doane) of the terrible consequences of a sinful life apart from God, and urges them to be reconciled to God through Christ.