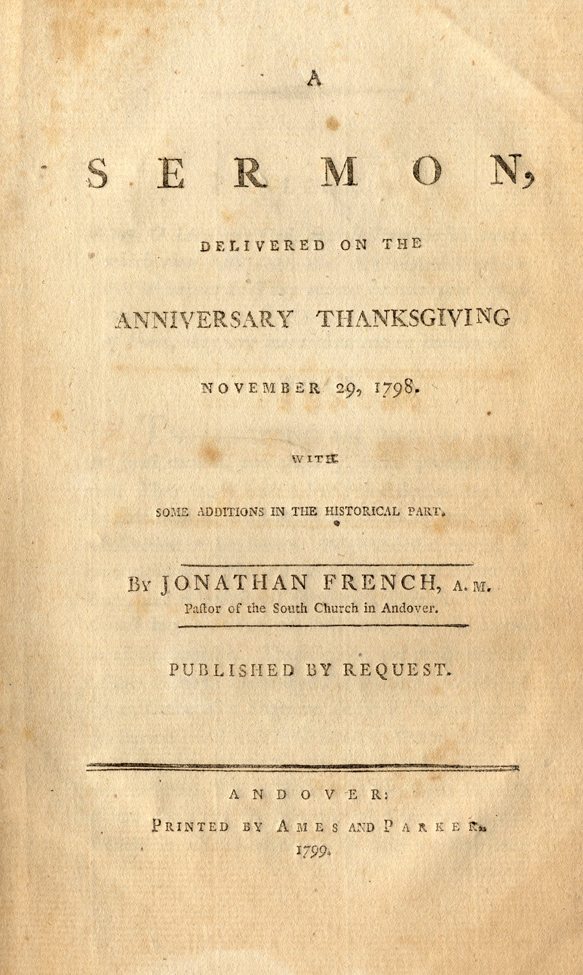

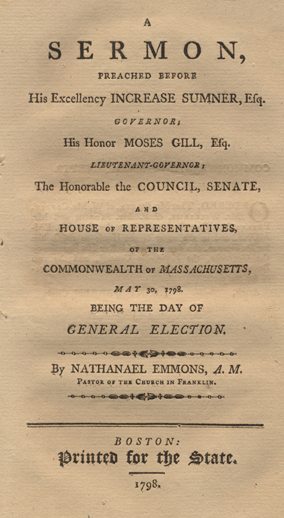

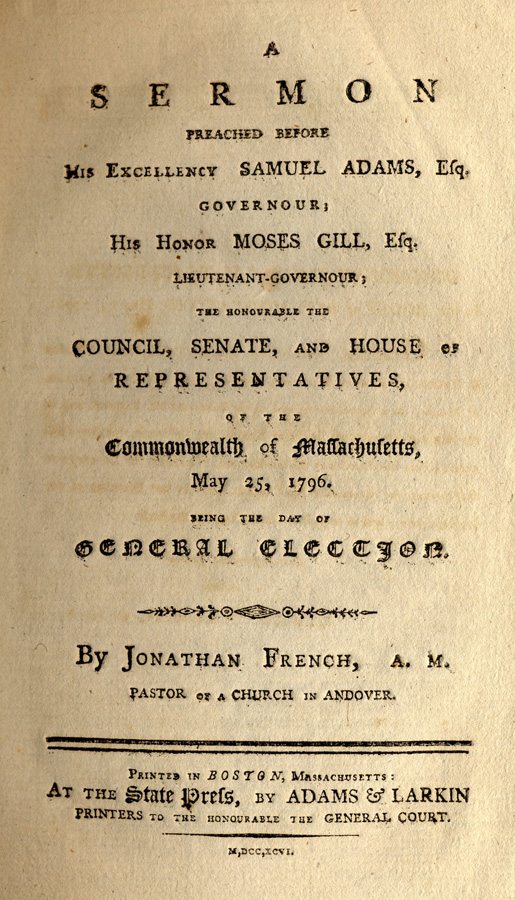

Jonathan French (1740-1809) preached this sermon in Massachusetts on May 25, 1796.

S E R M O N

PREACHED BEFORE

His Excellency SAMUEL ADAMS, Esq.

GOVERNOUR;

His Honor MOSES GILL, Esq.

LIEUTENANT-GOVERNOUR;

THE HONOURABLE THE

COUNCIL, SENATE, AND HOUSE OF

REPRESENTATIVES,

OF THE

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS,

May 25, 1796.

BEING THE DAY OF

GENERAL ELECTION.

By Jonathan French, A. M.

Pastor of a CHURCH in ANDOVER.

In the HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES, May 25, 1796.

Extract from the Journal.

Attest.

HENRY WARREN, C. H. R.

Election SERMON.

WHEREFORE YE MUST NEEDS BE SUBJECT,

NOT ONLY FOR WRATH, BUT FOR CONSCIENCE SAKE

The Apostle Paul appears to have been an adept in philosophy, ethics and politics. In his acquaintance with human nature he was equaled by few. Knowing the will of his divine Teacher, and having imbibed his spirit, with irresistible arguments, enforced by a captivating address, and all the power of rhetoric, he inculcated the interesting doctrines and sacred maxims of Christianity. Well versed in the principles of civil government, and knowing the importance of the influence of Christianity upon the minds and conduct of men to the happiness of civil society, as well as to their preparation for another and more glorious state, with the authority of an Apostle inspired by the Holy Ghost; and commissioned from the King of Kings, he solemnly exhorts, “let every soul be subject to the higher powers that be, are ordained of God.” The meaning undoubtedly is, that civil government, through the instrumentality of men, was instituted by the providence of God, for the benefit of mankind, On this principle, civil magistrates are appointed, not for their own honor, emolument or aggrandizement, but to promote private and public peace and happiness, by discountenancing vice, and encouraging virtue and religion. To such a government, well administered, Christianity requires peaceable and quiet subjection; and enforces it with this solemn denunciation against those, who resist such a government; they resist the ordinance of God, and shall receive to themselves damnation.—Such subjection is required not from a principle of feat only, but for conscience sake. The Apostle means a conscience enlightened by the principles of Christianity, and sanctified by the spirit of grace. We must therefore be subject, not for wrath only, but from a still higher motive, a sense of obligation to Deity and the indissoluble bonds of conscience.

The words of the text may therefore properly stand as the head of the following discourse; in which a few thoughts may be suggested upon the necessity and importance of virtue and religion to the support and success of civil government.

The Apostle does not prescribe any particular form of government: This is left to the wisdom and discretion of men; with which Christianity never intermeddles. It is evident from the Apostle however; that government ought to be founded upon the just rights of mankind, and to be administered for the best interests of society. They greatly mistake the Apostle therefore, who suppose him to favor the horrid doctrine of passive obedience and non-resistance. Such language is fit only for a despot to an untaught, barbarous people. If this were the Apostle’s meaning, no opposition ought to be made to the greatest tyranny on earth. No revolution might then take place; but men, like brutes, must submit to still more brutish men; patiently wear the galling yoke, and drag out the burden of life in miserable servitude without resistance.

The Apostle teaches no such doctrine. Christianity is by no means adapted to encourage oppression and tyranny. No form of government yet constructed, ever was so congenial to Christianity, as a well regulated Republic. No religion, ever yet known, is so conformable to the genius of a free government, as Christianity.

Whoever critically attends to human nature, the design of civil government, and the influence of religious principles on the minds and conduct of men, will easily perceive how essential morality and religion are to the peace and happiness of civil society. There are in mankind a variety of desires and passions, whence all their actions proceed. In the present state of human depravity, unhappily for us, these desires and passions are frequently at variance with each other.—This circumstance, in spite of philosophy and natural religion, will create a clashing of interest, that will produce those different opinions and opposing actions, whence distressing evils may ensue. To prevent such mischiefs, the invention of civil government undoubtedly took its rise. If the desires and passions of men were duly regulated, civil government and penal laws would be unnecessary. Men would then never err, except through misapprehension, which information and the benevolent affections would always rectify.—But human nature is possessed of the passions of selfishness and ambition, envy and jealousy, which unrestrained would produce discord, strife, and every evil work.

Civil government is a kind of machine, which the necessities of mankind have compelled them to erect for the restraint of such desires and passions as, if let alone, would be ruinous to the public peace and happiness of society. These machines ought to be so constructed and managed, as in their operations to effect that public peace and happiness, which may be sensibly felt, and realized by the people. But these machines require something more, than the power and influence of penal laws, to preserve them in order, and promote their great and important uses. The great art of managing government well consists in laying the desires, the passions and lusts of men under proper restraint.—But how can this be done? The experience of ages decides that penal laws alone are inadequate to the purpose. Though in many instances they may be efficacious, yet in general they do not reform the depraved minds of the lawless, nor correct the vicious habits of the licentious. Fear of punishment may prevent many crimes; but, as it does not destroy the desires and passions which originate them, whenever this fear, through the hope or prospect of impunity, subsides, the same passions will again urge on to licentiousness and criminality. Human reason and philosophy are not of themselves sufficient to secure the permanent peace and happiness of society from the depredations of licentious desires and passions. Further aid beyond anything civil government abstractedly considered embraces, is necessary to support it, and to secure the liberties and happiness of the people. Religion proffers this aid. The very design of Christianity is to reform mankind, to meliorate their tempers, to bring them to discharge their duty to God, and one another, and through the merits of the Redeemer to fit them for happiness in the world to come. The spirit of the religion of Jesus, thoroughly imbibed, would check all dangerous aspiring ambition, and those restless jealousies, which so often disturb the peace of mankind. Christianity embraces the true principles of free governments, as founded, not in usurpation, tyranny, or oppression, but in the true freedom and happiness of mankind. Divine revelation describes the character of good rulers, as men of wisdom and understanding; and requires that they be able men, such as fear God, and hate covetousness. Thus said David, the spirit of the Lord spake by me, the God of Israel said, He, that ruleth over men, must be just, ruling in the fear of God. Such rulers are not a terror to good works, but to the evil. They are Ministers of God for the good of the people. The sacred Oracles teach us, that, though they live, as God upon the earth, they must die like men, and be accountable to him, by whom Kings reign and Princes decree justice; who taketh not bribes, and is no respecter of persons.

If a government usurp an authority, and claim the exercise of a power, with which they never were invested; or if one branch of government should leap its own prescribed limits, and invade the prerogative of another; or if the people should claim the exercise of that authority, which they have delegated to their rulers; in all such cases the order and harmony of government will be necessarily interrupted, the public felicity suffer, and the liberties of the people be endangered. Hence such contests may arise between peace and faction, government and anarchy, as will shake, if not destroy, the very foundation of public happiness. To prevent these fatal evils, Christianity requires that nothing be done through strife and vain glory. But that each in lowliness of mind esteem others better, than himself. That everyone study to be quiet, and to do his own business; not going beyond, nor defrauding others in any matter. Christianity teaches to render to all their dues; tribute, to whom tribute; custom to whom custom; fear, to whom fear; honor, to whom honor. We are not to speak evil of dignities; nor use our liberty for a cloak of maliciousness, but as the servants of God. We are to lead quiet and peaceable lives in all godliness and honesty; and in all things, whatsoever we would that men should do unto us, even so to do unto them. All this is to be done from love to God and our neighbor, and from a religious regard to duty.

No substitute was ever yet found equal to virtue and religion for the support of order and good government. They, who reject these, may boast of their constitutions, their laws and administration; but neither the wisest constitutions, most rigid laws, nor strong nerved officers, dreary prisons, nor severest punishments without aid of virtue and religion can secure the permanent felicity of civil society. The boasted powers of philosophy, of natural reason, and national honor are all too feeble or capricious to be depended on to effect that manly, that regular, and uniform mode of conduct, which is the natural offspring of virtue and religion. Natural religion is of high importance, and its inducements to righteousness and truth, peace and good order are numerous and weighty; but they fall far short of the motives of Christianity and give less security to the liberty and happiness of civil society. The influence of the former terminates with this life; but the latter embraces motives drawn from the consideration of a future state; that the actions of men as moral agents will be rewarded or punished in the world to come. These are motives the strongest and most influential, that can apply to the consciences of men. Without these the public, in many cases, can have no security. The conscientious man, in full belief of the existence of God, and the truth of Christianity, as an honest man and sincere Christian, acts as under the eye of the all seeing and heart searching Deity, who will bring every secret thing into judgment, punish the guilty, and beautify the meek with salvation.

But what has the infidel to do with conscience, whose mind is contaminated with unbelief? Whose principles are destructive both of religion and morality; and whose conscience is feared as with an hot iron by deeply rooted vicious habits? What dependence can society place on such characters? A foe to God is not a friend to man. Restraining laws, necessary as they are for the prevention of crimes can never reach the evil of abandoned principles and vicious habits, so as to effect a remedy. Such characters may sometimes act for the public good; but this is only, when such a line of conduct coincides with some favorite passion—They always change with the current of their passions and interests. Such men are unstable in all their ways.

In connection with the power of conscience, we may instance the importance of the influence of religion, in the use of lawful oaths. An oath is a solemn appeal to God, for the truth of what is affirmed or promised: It implies an imprecation of the just and righteous judgment of God, if what the person declares, be not true; or if, in what he promises, he should not be faithful. An oath is therefore a solemn religious act, implying the imprecation of the wrath of God upon a person, if he be guilty of perjury. Dreadful is the punishment threatened in such cases. A curse shall enter into the house of him that sweareth falsely by the name of the Lord!

The utility and necessity of oaths in cases of evidence and in laying a person under solemn obligation to fidelity, in the discharge of the duties of his office, have been known and acknowledged among most nations. An oath of confirmation, says the Apostle, is an end of strife. As a kind of sanction to the lawfulness and utility of oaths in important cases, the Deity himself, graciously an oath. Oaths of evidence and of office are of so much importance, that civil government would be unsafe without them. It would be difficult, if not impossible to invent a substitute, that would answer the purpose. “Because, as one observes, the obligation of an oath reacheth to the most secret and hidden practices of men, and takes hold of them in many cases, where the penalty of human laws can have no awe or force upon them.” But what is the oath of an infidel, or of a man void of religion? What security can the public have from the oath of a person, who does not believe there will e a future state of rewards and punishments? What obligations of conscience can such a person feel? His taking the form of an oath while he is regardless of that being, by whom he swears, is no better, than solemn mockery. The public, it may be repeated, have no security from such oaths. The utility and necessity of oaths therefore, to the public safety and happiness evince the necessity of religious principles and virtuous habits. IN the days of Polybius such, we are told, was the corruption of the principles and morals of the people of Athens, that, “no Greek could be trusted on the security of his oath.” But in the republic of Rome, antecedently to their abounding licentiousness, such was the impression of their religious principles and virtuous habits on young minds, “that no Roman was ever known to violate his oath.”

The passions of men, unawed by religion and conscience, are dangerous, and ruinous to the freedom and happiness of civil society.

When loose principles, ungovernable passions, and vicious habits take place of morality and religion; ambition and avarice, revenge and thirst for dominion in the disappointed, or envy against those, who rise above them in wealth and honor, united with dishonesty and intrigue, sow the seeds of discord among the people, excite jealousies, raise factions, and disturb the public tranquility; and, if unrestrained, would throw government, yea even the world itself into confusion.

The evil effects of irreligion and immorality may be exemplified from the universal history of mankind. A few instances may be sufficient to confirm the subject.

Whoever attends to the history of that ancient nation, the Jews, will find these observations verified. When Balaam found that every other expedient to bring destruction upon Israel failed, he laid a diabolical scheme to corrupt and debauch the morals of the people, and by this mean effected their ruin. To the same cause, the corruption of principles and morals, may be traced the final destruction of the Jewish policy, church, and state.

The ancient republic of Sparta through the extraordinary policy and rigid laws of Lycurgus, aided by principles and habits impressed upon the young mind by a singular mode of education, existed for almost seven hundred years. While it remained cemented by the force of principles and manners, it bore down all opposition, and bid defiance to the world. But it finally fell a sacrifice to dissolute manners and lawless faction.

To similar causes may be ascribed the ruin of the famous, though short lived republic of Athens. Solon lived to see the fabric of freedom, which he had erected, fall to destruction. He gave them laws, which he acknowledged were not the best that might have been given, but the best they could bear. On his departure from Athens political storms arose; aided by an unprincipled licentious populace, demagogues took the lead, deluded the people, seized the stronghold, and established a system of tyranny. The freedom of Athens was never recovered. That once famed republic, overrun with ignorance and barbarism, now groans under Turkish tyranny, and Mahometan imposture.

The feuds and factions, which eventually proved the overthrow of the freedom, and the republic of Rome, may be traced up to the same destructive fountain of bad principles and dissolute morals of the people. “They adopted the luxury, the immoralities, and irreligion of other nations.” These in coincidence with their own passions effected their complete ruin. Thus that renowned republic, which nothing else could conquer, was conquered by its own vices. “A corruption of manners and numerous crimes, says a distinguished writer, made greater havoc in the city, than the mightiest armies could have done; and in that manner avenged the conquered globe.”

As human nature in all ages of the world is the same, like causes, under similar circumstances, in whatever period or part of the globe, will produce like effects. Happy will it be for America, if we avoid the rocks, against which so many others have been dashed in pieces.

Many important inferences and reflections, apposite to the present occasion suggest themselves from the subject.

If the influence of virtue and religion are so essential in preserving the freedom and securing the permanent felicity of civil society; the cultivation of good principles and virtuous morals among the people may be considered, as an object highly meriting the regard of our Legislative, Judicial, and Executive branches of government. What encouragement then should be given by our civil Rulers, by all influential men, and every class of citizens, to morality, religion and piety; and to all Christian institutions, as calculated to promote such happy effects.

If civil government thus needs the aid of good principles and virtuous habits, to render its operations happy and permanent, it must be a hazardous experiment for any nation under Heaven to reject that aid, on supposition that constitutions and human laws are sufficient without it, to secure peace and good order, and the rights and privileges of the people. Men may form constitutions, enact laws, display their philosophy, and exert all their eloquence in conjunction with coercion, but all will be insufficient for the permanent security of freedom and good government, without the aid of religion.

Reasoning from human nature and past events, we might venture to predict, if any nation should have the temerity to cast off morality and religion, as unnecessary to the happiness of civil society, it would in the event pay dearly for the experiment; and find, perhaps too late, that their own folly was their ruin.

From the foregoing observations we may infer the high importance of a virtuous education.

In countries, where religion is only the tool of states and of tyrants, the more ignorant the people are, the more easily they may be imposed upon and enslaved. It is the interest of such governments therefore, to keep the great mass of the people in ignorance. But, as mankind were not made for slavery, an enlightened virtuous people will never suffer themselves to be long enslaved. If, through supiness and inattention, tyranny should slip on the galling yoke, and fasten upon them the chain of slavery, they would soon feel their misery, and with a manly, virtuous resentment raise the all conquering arm of liberty, and break the yoke, as a with of straw, and snap the chain, as a spiders web.

A virtuous education is essential to the permanent felicity of all free governments. “The infant mind, says a writer of note, left to its own untutored dictates, inevitably wanders into such follies and vices, as tend to the destruction of itself and others.” “The early and continued culture of the heart can alone produce such upright manners and principles, as are necessary to check and subdue the passions of the soul; and liberty can only arise from a general subordination of these to the public welfare.”

Education in general forms the characters of men. Principles instilled into the mind, and habits formed in early life, lay a foundation, for the happiness or misery of the world. They verify the sacred maxim, train up a child in the way, he should go; and, when he is old, he will not depart from it.

Impressed with these ideas, our pious ancestors made the earliest exertion for the diffusion of knowledge, and the promotion of morality and religion among the people. Their design has been happily aided by many Christian Patriots, whose numerous charitable donations for the promotion of knowledge and religion, while they have so greatly served to advance private and public happiness, have at the same time laid up for the pious and charitable donors a rich inheritance in heaven!

We are happy in living under a government, where the great object of promoting learning and religion has arrested the attention of our wise and patriotic Legislators, who from time to time have enacted such laws, as, if carried into execution, would prove the grand palladium of our republic. Our Legislators have declared that “a general dissemination of knowledge and virtue is necessary to the prosperity of every state, and to the very existence of a Commonwealth.”

To promote the great design of a virtuous education, a present existing law of this Commonwealth, makes it the “duty of the President, Professors, and Tutors of the University in Cambridge, Preceptors of Academies, and all other Instructors of youth, to take diligent care, and to exert their best endeavours, so impress on the minds of children and youth committed to their care and instruction, the principles of piety, justice, and a sacred regard to truth, love to their country, humanity and universal benevolence, sobriety, industry, and frugality, chastity, moderation, and temperance, and those other virtues, which are the ornament of human society, and the basis, upon which the republican constitution is structured; and it shall be the duty of such Instructors; to endeavor to lead those under their care (as their ages and capacities will admit) into a particular understanding of the tendency of the before mentioned virtues, to preserve, and perfect a republican constitution, and to secure the blessings of liberty as well, as to promote their future happiness; and the tendency of the opposite vices to slavery.”

May this monument of the wisdom and patriotism of the Legislature, who framed it, be as lasting, as the world.

This leads us to reflect upon the importance of entrusting the instruction of youth to those only, who are persons of religion and good morals; who will teach by example as well, as precept.

Happy will it be for these rising States, if our Legislative and Executive branches of government be impressed with the idea, that without close attention to the virtuous education of youth, republicanism, freedom, and public happiness can never be preserved.

From a regard to the happiness of the people, private and public, present and future, our civil fathers, we may hope, will give every encouragement to literary and religious institutions. Parsimony in the support of education and religion is a kind of sacrilege, in which we cheat ourselves and the rising generation, injure the public, and rob God of his due.

If morality and religion be thus essential to public happiness and the support of free governments, it must then be of high importance, that our rulers be virtuous and good men.

I believe it may be considered, as an unfailing maxim, that no man can in heart be a true republican, who is not a person of piety and good morals. An infidel, immoral true republican is a solecism in language. Consequently no man, who is unfriendly to religion in profession or practice, ought to be entrusted with any important concerns in government. If it be pleaded, that bad men in many instances have done great good to the public; it may be replied, this happens only, when the selfish principles and passions chance to coincide with the public good. Such cannot be confided in. Special caution ought to be used against all those, who treat Christianity with contempt. Whatever such men may pretend, I appeal to the serious part of the community, whether an enemy to the cross of Christ can be a friend to mankind? The liberties of the people can never be safe in the hands of unprincipled men. While the following maxim remains an eternal truth, “That can never be politically right, which is immorally wrong;” an unprincipled man can never be a good politician, and ought never to be confided in by the people.

The example of wise and religious rulers, if justly esteemed, will have great influence upon the people.—For, in a general way, we may say with the wise son of Sirach, “As is the judge of the people himself, so are his officers; and what manner of man the ruler of the city is, such are they, that dwell therein.” From the imitative nature of man, the power of example lays an indispensible obligation upon rulers, and upon all influential men, to exhibit an example of virtue and piety in all their words and actions.

Happy must it be for that people, whose rulers feel the weight of this obligation. Bad examples are always contagious. The higher men are called in life, the greater in general is the influence of their example. If legislators disregard the laws, they have framed, they practically declare such laws are of no consequence.—One of the most effectual methods, to induce men to obey the laws, is for those, who prescribe them, to set the example. Highly favored is that people, whose legislators may each, with an honest heart say, as a great and wise ruler in Israel said to the people, “look on me, as I do, so do ye.”

In every view it must be the highest wisdom in all elections to have an eye to the religious character of men as well, as to the other qualifications. What can have a greater influence upon the minds and consciences of Rulers, to excite them to fidelity in discharge of their duties of their office, than an habitual sense of the all seeing eye of Deity, joined to a firm persuasion, that the most exalted, who live, as Gods on earth, must die like men, and appear at the awful tribunal of God, who is no respecter of persons, and be adjuged and rewarded according to their works.

If the influence of religion be so essential to public happiness; then the encouraging of virtue and piety, and discountenancing of all profanity, intemperance, profanation of the Lord’s day; all public shows, and plays, and everything, which tends to dissipate the minds, and corrupt the morals of youth, or the people at large, claim the attention of our wise and virtuous Rulers, the guardians of our laws and liberties. On some of these vices, particularly on profanity, intemperance, and profanation of the holy Sabbath, with their baneful influence upon society, I might expatiate, were it not that I should intrude too much upon your patience. One vice however I cannot forbear to mention. I mean slander or detraction. This, whether it proceed from the tongue, the pen, or the press, is an evil of the meanest, blackest die, and of the most mischievous tendency. Its envenomed shafts often aim a deadly blow at the fairest and most important characters, to wound and destroy that good name, which is better, than great riches; yea, that is next to life itself. When long tried virtue, distinguished merit, and signal services are repaid with ingratitude and abuse, an it be expected, that men of integrity will be willing to continue in the service of their country? If men of this character be driven from office, and others succeed them, who prefer private emolument to the public welfare, we shall, when too late, rue the folly and wickedness of that conduct, which produced the change. Slander is an evil of such magnitude, that no bounds can be set to its mischievous consequence. Well might the wise preacher call the defamer a madman, who casteth fire-brands, arrows, and death. With infinite reason did the inspired Apostle represent the defaming tongue, as a fire, a world of iniquity, that setteth on fire the course of nature; and as set on fire of hell.

There is nothing however, to be feared from an open, manly, honest, and decent investigation of public men and measures. The right of free discussion and private judgment is the glory of every free American. But, when this degenerates into falsehood, sourility, and personal abuse; no indignation nor contempt can be too great to be expressed against it.—Happy, thrice happy will it be for America, when the principles of Christianity, and the energy of good morals shall influence every heart, dictate every tongue, and guide in every action. Then will harmony of opinion, peace, and truth pervade every part of the United States. Then will wrath and bitterness cease, faction hide its monstrous head, iniquity be done away, and, the kingdom of the Redeemer flourish.

We must pass over many other inferences and reflections, which naturally suggest themselves from this fruitful subject.

This day recalls to our grateful remembrance, what we have heard with our ears, and our Fathers have told us concerning the great things our all gracious God hath done for this land. Our pious ancestors, on account of the dissoluteness of manners and licentiousness of the youth, among whom they resided, “and fearing their posterity through these temptations and vicious examples would degenerate, and religion die among them; for the sake of purity of worship, and liberty of conscience, and from a hope of laying a foundation for the propagation of the kingdom of Christ,” left all that was dear in their native country, and planted themselves in this then barbarous land.—From small beginnings, by a series of almost miraculous events, the United States have arisen into an extensive, flourishing nation.

And now, with respect to our constitutions, laws, and administration, civil and religious privileges, and with respect to our commercial and agricultural interests, may it not be affirmed, without an hyperbole, that we are the happiest nation, that has existed, since the morning stars sang together, and the sons of God shouted for joy at the creation of the world.

What gratitude is due to Heaven on this occasion, for our State and Federal governments, and for the precious privileges and blessings, we enjoy under them? With what grateful sensations should we remember that wise and valiant band of statesmen, warriors, and other patriots, whose great exertions have been employed in pulling down the strong holds of tyranny and oppression, and in rearing up the pillars of liberty, peace, and public happiness? To do full justice to whose characters, would beggar the power of language. May their memories remain indelibly engraven on the heart of every American! But who, O who can render adequate thanks to God for WASHINGTON—whose wisdom and integrity, firmness and magnanimity, have excited the astonishment of the nations of the earth, and added a new wonder to the political world!

What is wanting, to render our national happiness as complete, as the present state of things will permit, but a just estimate of the numerous public blessings, whereby we are distinguished from other nations, due gratitude to Heaven, and an expression of this gratitude by a correspondent behavior. We ought however, to remember that a state of prosperity is a state of danger. It excites envy abroad, and lulls to security at home. It presents us a mark for the wiles of those, who are well versed in intrigue; while our youth and inexperience render us unsuspicious of their stratagems, and poorly qualify us to detect and defeat them. While we are just and faithful in the fulfillment of our engagements to all, as free and independent States, may we be proof against foreign arts, and foreign influence from every quarter.

On this auspicious anniversary, while many nations are sitting in darkness, others are involved in the horrors of war, struggling for the blessings we enjoy, and are groaning to be delivered from calamity, to behold our civil fathers, the heads of our tribes, here peaceably assembled to transact the great affairs of state, what heart does not swell with gratitude to Heaven? What tongue is not ready to break forth into a song of praise.

His Excellency the Governor, his Honor the Lieutenant Governor, the honorable the Council, and the honorable the Members of Legislature, will please to accept my warmest and most respectful congratulations on this important, joyful occasion. May Almighty God take your Excellency and Honors into his most holy protection! Influenced by the best of principles, the peaceable religion of the Prince of Peace, may wisdom and unanimity attend your counsels and decisions; that the people may rejoice and say, blessed be the Lord God of Israel, who hath set such wise and good men to rule over us. Wherefore let us be subject, not only for wrath, but for conscience sake.

May the various branches of the State and Federal governments, under the influence of the religion of Jesus, each in its proper sphere, like the various orbs above, keep their proper places and balances, the one never encroaching upon, or interfering with the other, move on in harmonious rounds till time shall be no more!

If such be the importance of morality and religion to the support of the freedom and happiness of society; my much respected fathers and brethren in the ministry will never be wanting in their exertions to promote religious principles, and the Christian virtues among the people. I am happy in believing the great body of the Clergy, with a very few exceptions, are firm friends to our State and Federal governments, to our constituted authorities, to virtue and religion, peace and good order among the people. And, if their united exertions and patient sufferings in effecting the American revolution are marks of patriotism, may they not justly lay claim to the title of Christian patriots? When the divine Saviour commands us to render to Cesar the things that are Cesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s—When the inspired Paul solemnly charges Titus to put his hearers in mind to obey magistrates, and to be ready to every good work—When the inspired Peter solemnly exhorts his hearers to submit themselves to every ordinance of man for the Lord’s sake—When we hear the inspired Jude denouncing his anathemas against those, who despise dominion, and speak evil of dignities; with such divine commands, and enforcing examples before us, on any great emergency, should the Clergy show indifference, and not exert their influence to save their country; might not our divine Lord and Master say, as in another case, I tell you, if these should hold their peace, the stones would immediately cry out.—In every serious danger, on every important crisis, for Zion’s sake they will not hold their peace, and for Jerusalem’s sake, they will not rest, until the righteousness thereof go forth, as brightness, and the salvation thereof, as a lamp that burneth. They will plead that God will spare his people, that none among the nations of the earth may say of America, where is now their God?

In a word, may the consideration of the great importance of virtue and religion to our public and private happiness, both present and future, engage every class of citizens to cultivate the Christian temper, and to promote sobriety, peace, and good order in every sphere of action; that our peace may be as a river, and our righteousness, as the waves of the sea! May the holy Spirit of the Lord be poured out upon all the nations of the earth; and that kingdom, which consisteth in righteousness, peace, and joy in the holy Ghost, universally prevail! That instead of wars and bloodshed, Kings may become nursing Fathers, and Queens nursing Mothers to the people of God. Then will that ancient prophecy be fulfilled, the kingdoms of this world are become the kingdoms of our Lord, and of his Christ, and he shall reign forever and ever.

FINIS.

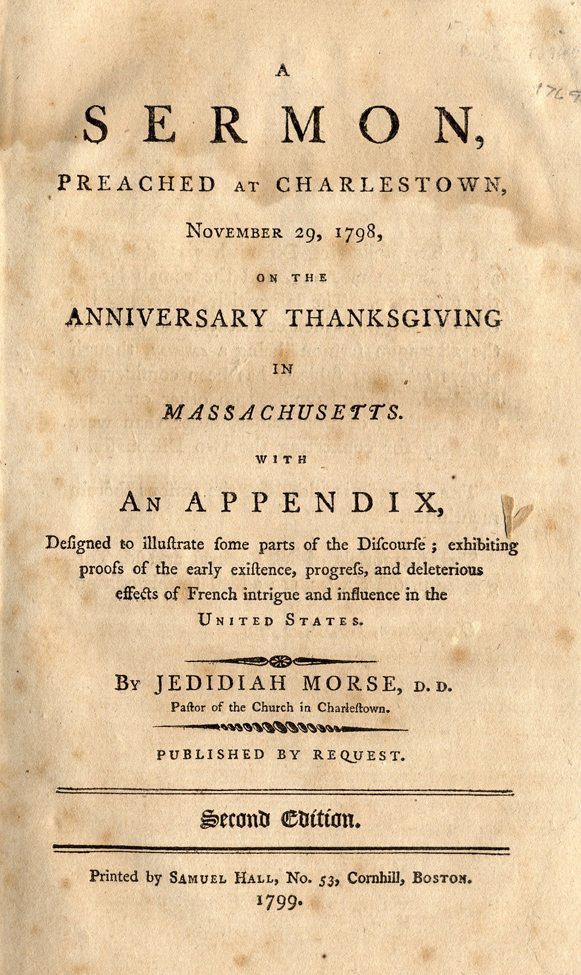

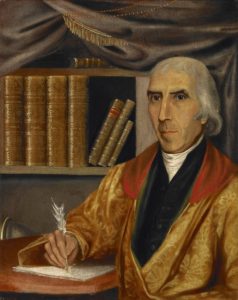

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Morse graduated from Yale in 1783. He began the study of theology, and in 1786 when he was ordained as a minister, he moved to Midway, Georgia, spending a year there. He then returned to New Haven, filling the pulpit in various churches. In 1789, he took the pastorate of a church in Charlestown, Massachusetts, where he served until 1820. Throughout his life, Morse worked tirelessly to fight Unitarianism in the church and to help keep Christian doctrine orthodox. To this end, he helped organize Andover Theological Seminary as well as the Park Street Church of Boston, and was an editor for the Panopolist (later renamed The Missionary Herald), which was created to defend orthodoxy in New England. In 1795, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity by the University of Edinburgh. Over the course of his pastoral career, twenty-five of his sermons were printed and received wide distribution.

Born in New Haven, Connecticut, Morse graduated from Yale in 1783. He began the study of theology, and in 1786 when he was ordained as a minister, he moved to Midway, Georgia, spending a year there. He then returned to New Haven, filling the pulpit in various churches. In 1789, he took the pastorate of a church in Charlestown, Massachusetts, where he served until 1820. Throughout his life, Morse worked tirelessly to fight Unitarianism in the church and to help keep Christian doctrine orthodox. To this end, he helped organize Andover Theological Seminary as well as the Park Street Church of Boston, and was an editor for the Panopolist (later renamed The Missionary Herald), which was created to defend orthodoxy in New England. In 1795, he was awarded a Doctor of Divinity by the University of Edinburgh. Over the course of his pastoral career, twenty-five of his sermons were printed and received wide distribution.