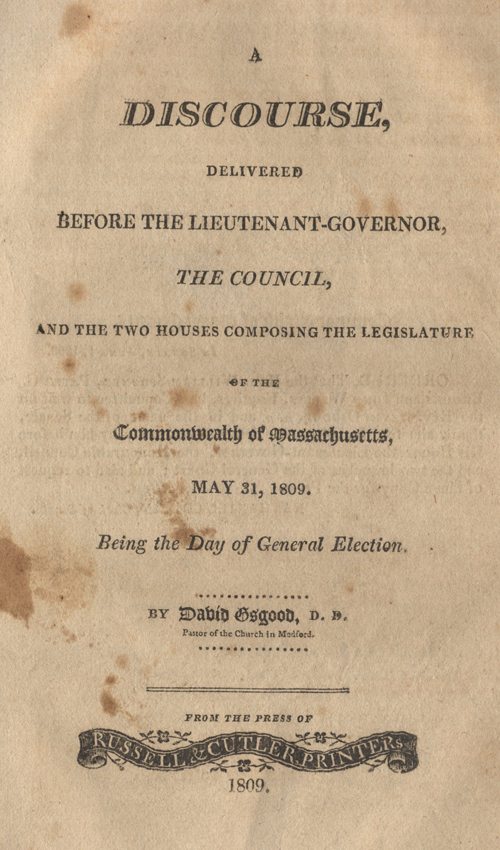

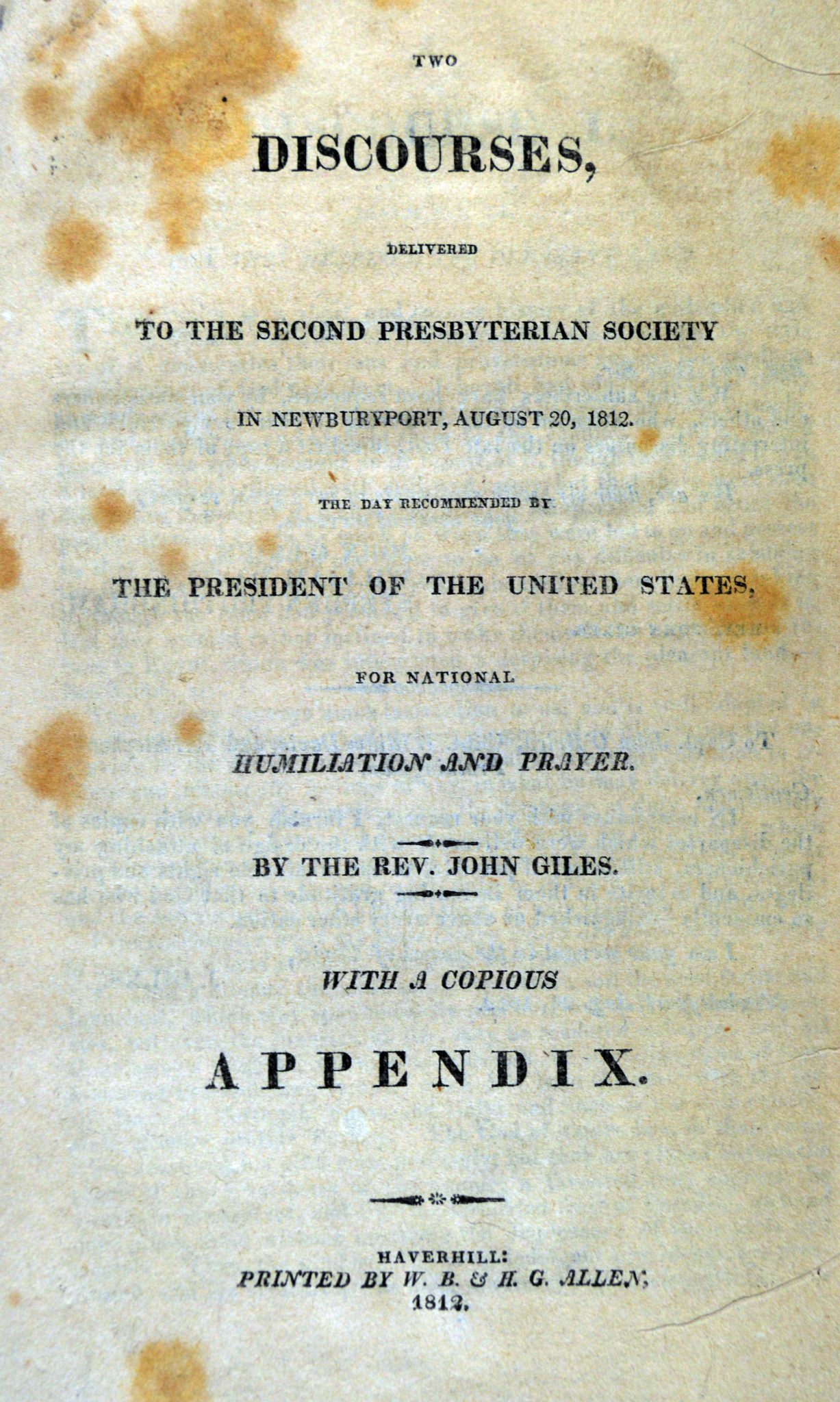

The following two discourses were given by Rev. John Giles on the occasion of a national day of fasting. This fast day had been proclaimed by President James Madison. Following these two discourses are “reviews” of them.

TWODISCOURSES,

DELIVERED

TO THE SECOND PRESBYTERIAN SOCIETY

IN NEWBURYPORT, AUGUST 20, 1812.

THE DAY RECOMMENDED BY

THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES,

FOR NATIONAL

HUMILIATION AND PRAYER.

BY THE REV. JON GILES.

Newburyport, Aug. 24, 1812.

Rev. and Dear Sir,

WE the subscribers have been requested, by your parishioners and others, who attended on the delivering of your very patriotic and interesting discourses on the late Fast, to solicit a copy of them for the press.

We are, dear sir, with sentiments of very great respect,

Your obedient servants,

JOHN O’BRIEN,

WILLIAM DAVIS,

STEPHEN FROTHINGHAM.REV. JOHN GILES.

To Capt. John O’Brien, Capt. William Davis, and Mr. Stephen Frothingham.

Gentlemen,

IN compliance with your request, I furnish you with copies of the discourses which were delivered, with the design of attaching my parishioners, still more, if possible, to our invaluable rights and privileges, and to incite in them increasing gratitude to that God who has so eminently distinguished us above every other nation.

I am your servant in the gospel of Christ,

J. GILES.

Newburyport, Aug. 26, 1812.

DISCOURSE I.

PSALM evi. 24.

YEA, THEY DESPISED THE PLEASANT LAND.

THIS Psalm is a short and concise history of the multiplied and unprovoked rebellions of the ungrateful Israelites; and the writer of it enumerates their sins and provocations against the goodness and blessings of God unto them. Jehovah had conducted them safely through scenes the most trying, and through dangers the most formidable and imminent, and brought them to the confines of the promised land; but the spies brought an ill report of it, though they owned it was a land which overflowed with milk and honey; but that there were such difficulties to possess it, which they thought insuperable; and hence the people despised it—in as much as when they were bid to go and possess it, they refused; and did not chuse to be at any difficulty in subduing the inhabitants of it, or run any risk or hazard of their lives in taking it, though the Lord had promised to give it them and settle them in it. But they seemed rather inclined to make themselves a captain, and return to Egypt, which was interpreted a despising the pleasant land.—See Numb. Xiv. 1.

This history conveys much instruction to us, and is well adapted to the designs of the day. And, before we proceed in illustrating and improving it; the speaker must premise, that it is not his intention to irritate and inflame the feelings of any, in what he may deliver upon the present occasion. His motives are, the discharge of duty, and publicly to avow his warm, firm, and decided attachment, to the country which has adopted him as its citizen, and to the illustrious character who at present presides over it; and to this duty he is urged by lively gratitude, and the solemn oath which he has taken, of undeviating allegiance to it.

First…Enquire what are those things which are absolutely necessary to constitute a land pleasant. And we observe,

1. That a climate the most salubrious, and a soil the most fertile and luxuriant, which may spontaneously produce, not only all the necessaries, but even the luxuries of life, may be rendered unhappy, and all these sweets blighted, and marred, through the intruding hand of some assuming and unfeeling tyrant. Such has been the state with the fertile lands of Portugal, Spain and Italy; and such is the still existing state of more prolific Turkey. The God of nature has, in those countries, scattered his gifts most profusely; but they are placed beyond the reach of the great mass of the people; a favoured few, engross the sweets to themselves, and like the forbidden fruit of Paradise, no hand dare pluck them without incurring the displeasure of their lords and masters. Thus, the kind bounties of an indulgent providence, are prostituted, and his creatures, who have a natural right to enjoy them, are tantalized with having them in continual view, but never are filled with the sweetness of them. This must turn the most pleasant and fruitful land into a sterile and painful wilderness; a land, which none of us, my hearers, would chuse as his home to dwell in, or as his place of sojourneying.

2. To render a land pleasant, its inhabitants must enjoy equal rights and privileges, otherwise it can be only to a favoured few, while the great majority are rendered objects of misery, through penury and distress; and thus, the comforts and blessings of civilized society, be abused and subverted, and even prostituted to the most ignoble and basest of purposes. We will demonstrate and illustrate this, not only from ancient, but modern governments. And here we observe, that society in every state is a blessing; but government in its best state is but a necessary evil,—in its worst state, an intolerable one. For when we might expect in a country without government, our calamity is heightened, by reflecting that we furnish the means by which we suffer.—Government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence. The palaces of kings, are built on the ruins of the bowers of Paradise. In ancient Greece, monarchy was the government which they first formed; but this they soon found degenerate into tyranny. Hence the term tyrant, was justly applied to them. And, indeed, the word originally signified no more than king, and was anciently the title of lawful princes. But monarchy gave way to a republican government, which, however, was diversified into almost as many various forms as there were different cities, according to the different genius and peculiar character of each people. But still there was a tincture, or leaven, of the ancient monarchical government, which frequently inflamed the ambition of private citizens, and made them desire to become masters of the country. In almost every state of Greece, some private persons advanced themselves, by cabal, treachery and violence, and exercised a sovereign authority, with a despotic empire; and in order to support their unjust usurpations, in the midst of distrusts and alarms, they thought themselves obliged to prevent imaginary or suppress real conspirators, by the most cruel proscriptions, and to sacrifice to their own security, all those whom rank, merit, wealth, zeal for liberty, or love of their country, rendered obnoxious to a suspicious and unsettled government, and which found itself hated by all, and was sensible it deserved to be so. What we have remarked of Greece, will, with a few shades of difference, apply to ancient Rome.

Let us now take a view of the modern governments of Europe, and examine how far they are calculated to add to the peace, comfort and happiness of mankind; and in the attempt our souls must overflow with gratitude to God, if sensible of the superior blessings and privileges we enjoy in this our favoured land. For,

3. A land to be pleasant, must have governors and magistrates, qualified and suited to the dignity and high stations they fill; nor can they command the respect and affection of those they rule over, unless they are the men of their choice. For the truth of this, I appeal to your judgment. Should we feel happy, were a man to be forced upon us, as governor of this state, or as president of the United States? And, granting the man, even qualified, in every point of view, would not our feelings revolt? But should such an one act the part of a tyrant, by oppressing your persons, taking from you your property, and reducing you and your posterity, from affluence to extreme want and beggary, the case would be still more afflicting. This representation is not ideal; it exists in all the aggravating circumstances here stated, and that in the fast-anchored isle of Great-Britain. The chief magistrate, or what they call king, is hereditary. How degrading this to an enlightened people! It is a system of mental leveling. It indiscriminately admits every species of character to the same authority. Vice and virtue, ignorance and wisdom, in short, every quality, good or bad, is put on the same level. Kings succeed each other, not as rationals; it signifies not what their mental or moral characters are. Such a government appears under all the various characters of childhood, decrepitude, and dotage; a thing at nurse, in leading-strings, or in crutches. It reverses the wholesome order of nature; it occasionally puts children over men, and maniacs to rule the wise. It requires some talents to be a common mechanic; but to be a king requires only the animal figure of a man, a sort of breathing automation. But I must observe, that I am not the personal enemy of kings. No man more heartily wishes, than myself, to see them all in the happy and honorable state of private individuals. But I am the avowed and open enemy of what is called monarchy; and I am such, by principles which nothing can either alter or corrupt—that is, by my attachment to humanity—by the anxiety, which I feel within myself, for the ease and honor of the human race—by the disgust which I experienced, when I observed men, directed by children, and governed by brutes—by the horrors, which all the evils that monarchy has spread over the earth, excite within my breast—and by those sentiments, which make me shudder at the calamities, the exactions, the wars, and the massacres with which monarchy has crushed mankind. Would not you, my hearers, consider such a land, however salubrious the clime, however fertile the soil, however embellished with the progress of the arts and sciences, deprived of its birth-right and groaning under special marks of divine displeasure? Let us rejoice, that we are in the full possession and free exercise of the privilege of selecting from ourselves men to be our rulers; and while we give them a compensation for the services which they render the public, in their several stations, which is but just and reasonable; for the labourer is worthy of his hire. Yet government in America is what it ought to be, a matter of honour and trust, and not made a trade of, as in England, for the purpose of lucre.

4. That which constitutes a land pleasant, is the state of society. To see every member of it in the enjoyment of all the essential necessaries of life; we do not mean, that one and all should possess equal property, for this never was designed by the God of nature; for there will be some who are comparatively poor, for the exercise of the benevolence of the rich. But that none should suffer through want or hunger, all who are in the enjoyment of health, and are industrious, should be able by moderate labour, to procure the comforts of life. We bless God that such a pleasant land is our inheritance. Here is a sufficiency of bread for all. Let the people here be but diligent, and a few years will place them in a state of independence. O how different is this, from what we see on the other side of the Atlantic! Should the enquiry be, what makes the difference, has not providence favored them with a fruitful land? We reply, providence has not been to them sparing in its gifts: but through the cunning craft of men, these gifts are engrossed by a few choice spirits, who riot in luxury, at the expense of the labourer, the mechanic and the husbandman. We will explain our meaning—The chief magistrate of England receives a million sterling every year; the other branches of his family, nearly the same sum, and a long list of placemen and pensioners, swell the burden to an enormous size. And all this is wrung from the hard earnings of the laboring poor. It is this wretched system which causes the land to mourn, which crowds the streets with beggars, and which drives men to the desperate act of invading the property of others; for what will not hunger impel men to! This picture is not overcharged; some present have seen with their eyes, these things, and can bear witness to the facts. But let us turn our view from these sickening scenes, and contemplate our own condition on these happy shores, and we see an extent of territory, twelve times larger than England, and the expense of the several departments of the general representative government not amounting to what is allowed even to the king alone.

5. To render a land pleasant, it is essential that the means of grace should be enjoyed. It is these which add to the glory of any land, and render a people truly great. This it was, which made the Israelites so much greater than other nations. Thus Moses describes them: “What nation is there so great, that hath statutes and judgments so righteous, as all this Law which I set before you this day?” Without the Gospel, the most enlightened people, are no better than refined savages. The Gospel is a pearl of great price; it is the glory and honour of a church, a people, or a person. This only instructs us in the way of salvation. Trade and commerce, may gain and preserve an estate, bread may support the body, but this only can nourish and prop up the soul. When the Gospel is removed, the light is removed which is able to direct us, the pearl is removed which can only enrich us. In the want of this, is introduced a spiritual darkness, which terminates in an eternal darkness. As the Gospel is compared to Heaven, and so called the kingdom of heaven; and a people in the enjoyment of it are said to be lifted up to heaven; so in the want of it, they are said to be cast down to hell. See Matt. 10, 23. So that what resemblance there is between heaven and the means of grace; that there is between the want of them and hell. Both are a separation from God; so that when the Gospel departs, all other blessings depart with it, and judgments succeed. When the glory of God was gone up from the first cherub to the threshold of the house, see Ezek. 9, 3. The angels are commanded to execute the destructive sentence against the city. Ver. 4, 5. When the word of God is removed, the strength of a nation departs. The ordinances of God are the towers of Sion. The temple was not only a place of worship, but a bulwark too. The ark was often carried by the Israelites into the camp, because there their strength lay. And when David was chased away by his son Absalom, he takes the ark of the tabernacle, as his greatest strength against the defection of his son and subjects. This blessing, my hearers, we enjoy in a peculiar manner. The heavenly manna profusely descends around our tents, and every one may worship God in that form and manner which he thinks accords best with the volume of inspiration.

6. That which renders our land the glory of all lands, is to be free from all religious establishments, the bane of society, and curse of human nature. Let us enlarge a little on this sentiment. All religions are in their nature mild and benign, and united with principles of morality. They could not have made proselites at first, by professing anything which was vicious and persecuting or immoral. How is it then, that they lose their native mildness, and become morose and intolerant? It proceeds from an alliance between church and state. The inquisition in Spain and Portugal, does not proceed from the religion originally professed, but from this mule animal, as one calls it, engendered between church and state. The burnings in Smithfield, proceeded from the same heterogeneous production; and it was the regeneration of this strange animal, afterwards, in the nation now called the bulwark of our religion, which revived rancor and irreligion among the inhabitants there, and which drove the people called dissenters and Quakers to this country. Persecution is not an original feature in any religion; but it is always the strongly-marked feature of all law-religions, or religions established by law. Take away the law-establishment, and every religion reassumes its original benignity. Here in America, a catholic priest is a good citizen, a good character, and a good neighbor; the same may be said of ministers of other denominations, and this proceeds, independent of men, from their being no law-establishment in America.

The constitution of the United States hath abolished or renounced toleration, and intoleration also; and hath established universal right of conscience. Toleration is not the opposite of intoleration, but is the counterfeit of it; both are despotisms. The one assumes to itself the right of withholding the liberty of conscience, and the other of granting it. The one is the pope armed with fire and faggot, and the other is the pope selling or granting indulgences. The former is church and state; the latter is church and traffic. This is the perverted state of things in that kingdom, called the world’s last hope. And though the gospel is there preached, yet it is the misfortune of many who love it, to have a minister imposed upon them, who is an enemy to it; and which minister they must support, with the tenth of their tithes; even though dissenters from the established church; and what adds to the turpitude of all this, no man can hold any place of trust or employ under the government, who is not an Episcopalian, without first receiving the sacrament of the Lord’s Supper, on his bended knees, to qualify him for office. Must it not be duplicity, nay, the very essence of hypocrisy, in any man, to call such a kingdom, “the bulwark of our religion.”

Use I. Let us to-day, deplore, and lament over our manifold sins which have tempted God to let loose upon us one of his sore judgments. The sword is drawn, and more than probable, while I am addressing you, it is bathed in the blood of some of our fellow-citizens. It is true that at present, through mercy, it is placed at the distance from us; but some on our frontiers, and on the sea, have already fallen sacrifices, and we know not how soon it may be permitted to approximate our habitations. The fate of war is always precarious and uncertain. Let not him who putteth on his armour, boast like him who putteth it off. Remember it is God alone who giveth us the victory. Let our eyes then be directed to him, and all our expectations from him. This by no means supersedes the necessity of our warmest exertions. No, it is the sword of the Lord and Gideon. Let us then assist the brave, generous defenders of our country, who are vindicating our rights, and redressing our wrongs. Let us, I say, assist them by prayer and fervent cries, for prayer has ever proved a powerful weapon. If it overcomes God, it certainly will overcome men. Thus, while the hand of Moses was upheld by the prayer of Aaron and Hurr, he prevailed in the battle against Amalek. And it is promised, that one such, shall chance a thousand, and two, put ten thousand to flight. Thus Jehoshaphat, after he had proclaimed a fast, when a great multitude came against him, addresses God in prayer: O, our God, wilt thou not judge them, for we neither know we what to do , but our eyes are upon thee. And when they began to sing, and to praise, the Lord routed their enemies, with a great slaughter.

2. Let us encourage ourselves in the Lord, from the nature of the enemy we are now engaged with. In our infancy, we humbled their most celebrated generals; one of which boasted on the floor of Parliament, that with 3000 men, he would march in triumph, from one end of our continent to the other. Part of his assertion seemed to be prophetic, for he passed through a section of our continent, not as a conqueror, but a crest-fallen prisoner. If we achieved such exploits in our infant state, what shall we net, through provident, be able to do now in our manhood? Add to this the multiplied crimes of the government we are opposed to; a government founded and cemented in blood, and its tottering state, still upheld by blood; a government with which, it is evident, the Lord has a controversy. How different the state of this, our happy land. Never had a country so many openings to happiness as this; her setting out into life, like the rising of a fair morning, was unclouded and promising; her cause was good; her principles just and liberal; her conduct regulated by the nicest steps, and every thing about her wore the mark of honour. Here I will give you the language of Mr. Rush, the orator of the day, at the seat of our government, the 4th of July last. When, let us ask with exultation, when have ambassadors from other countries been sent to our shores, to complain of injuries done by the American States? What nation have the American States plundered? What nation have the American States plundered? What nation have the American States outraged? Upon what rights have the American States trampled? In the pride of justice and true honour, we say, none. But we have sent forth from ourselves the messengers of peace and conciliation, again and again, across seas, and to distant countries—To ask, earnestly justice to sue, for a cessation of the injuries done to us. They have gone to protest, under the sensibility of real suffering, against that course which made the persons and the property of our countrymen, the subjects of indiscriminate and rapacious spoliations. These have been the ends they were sent to obtain. Ends too fair for protracted refusal, too intelligible to have been entangled in evasive subtitles, too legitimate to have been neglected hostile silence. When their ministers have been sent to us, what has been the aim of their missions? To urge redress for wrongs done to them, shall we ask again? No, the melancholy reverse. For in too many instances, they have come to excuse, to palliate, or even to endeavour, in some shape, to rivet, those inflicted by their sovereigns upon us.

We, my hearers, have nothing to fear eventually, in our contest with a government so depraved and corrupt, as that of the British. Her fictitious wealth is depreciating; her most wise and virtuous statesmen cannot be prevailed upon to join, and unite in her councils; her prince regent has, by his intemperance and debaucheries, reduced himself to the state of an idiot; and the multitudes of her poor, rendered desperate by hunger, are already threatening to overwhelm it with their vengeance. In short, every sign of the times, indicates her speedy dissolution. Certainly the righteous God will not suffer her wicked and horrid ravages to go unavenged, even here upon earth. Let us wait awhile, and we may live to see the time, wherein it shall not be said by the voice of faith, but by the voice of sense itself, Babylon, the great, is fallen, is fallen!

DISCOURSE II.

PSALM 106. 24.

YEA, THEY DESPISED THE PLEASANT LAND.

The speaker, in the forenoon, called your attention, to the distinguishing goodness of God, which has exempted us as a people, from the burdens, oppressions, and calamities, under which the nations of Europe groan, and which wring from the inhabitants, the most piercing cries. Our lines are fallen in pleasant places: yea, we have a goodly heritage: but some among us, like Jeshurun of old, have waxed fat and are kicking against the rock of salvation. This leads us,

Second…To exhibit the characters who despise the pleasant land.

We charge no party, solely, as implicated in this crime; but shall attempt to demonstrate that there are such men among us. And we will, as we proceed in our description, adhere to the criterion laid down by our Saviour—you shall know them by their fruit.

1. Men may be said to despise it, when they make light of their privileges, either in a natural, moral, or political view.

First, in a natural view. The Mercies, which we call natural, are those which are necessary for our nourishment and support; and that we, as a people, abound in these, is evident to all. We live in a land ever-flowing with a rich variety of God’s providential goodness Here is no leanness of teeth; our streets are not crowded with our fellow-creatures, soliciting the aid of our benevolence—nor our ears assailed with the melancholy tales of indigence and distress. The parent, with pallid cheeks, hollow eyes, and trembling limbs, arrest not our steps with importunate cries for relief to their helpless infants, pining in want, and the lamp of life ready to expire, because destitute of means to nourish it. We are placed far from these sickening scenes. But, alas! Do we not make light of these mercies? We enjoy the mercies, and forget the donor. We take what he gives; but pay not the tribute he deserves. The Israelites forgot God their Saviour, which had done great things in Egypt. We send God’s mercies, where we would have him send our sins, into a land of forgetfulness; and write his benefits, where he himself will write the names of the wicked; in the dust, which every wind effaces. We forget his goodness in the sun, while it warms us—in the showers, while they enrich us—and in the corn, while it nourishes us. It is an injustice to forget the benefits we receive from man, but a crime, of a higher nature, to forget those dispensed to us by the hand of God, who gives us those things which all the world cannot furnish us without him. It is, in God’s judgment, a brutishness beyond that of a stupid ox, or a duller ass. The ox knoweth his owner, and the ass his master’s crib, but Israel doth not know, my people do not consider. How horrible, that God should lose more by his bounty, than he would by his parsimony. If we had blessings more sparingly, we should remember him more gratefully. If he had sent us a bit of bread in distress, by a miracle, as he did to Elijah, by the ravens, we should retain it in our memories. But the sense of daily favours, soonest wear out of our minds, which are as great miracles, as any in their own nature, and the products of the same power.

Secondly. We despise our moral and spiritual privileges, when we reject the truths of revealed religion. This is one of the crying sins of our land. Errors which were almost obsolete, are reviving, and the professors of those pernicious doctrines, are daily multiplying and increasing, by which the glories of Christ are laid prostrate in the dust; and the object of the Christian’s dearest hope is degraded, and brought down to a level with a creature, so that we had need to tremble at the prospects before us; for these sentiments, like the explosion of a subterraneous fire, may ere long burst forth and spread fain, slaughter, and death, all around, should they become the creed of an established religion. Let no one say, we live in an age too enlightened, for religious persecution to gain head. But stop; let us for a moment examine the force of this reasoning; and one remark shall suffice. Could any of you, venerable patriots, who joyfully took the spoiling of your goods, and waded your way through blood to gain the pinnacle of liberty, could you suppose, at the close of our national struggle, that in the year 1812, your fellow-citizens should become objects of persecution, for an attachment to those very sentiments, for which so many of our fathers bled and died? And who are the characters who foment and the very ringleaders of this intolerant spirit? Are they not those who profess the aforesaid sentiments?

Men despise the pleasant land, who make light of the gospel, and will not attend to the preaching of it; or if they give it a hearing, refuse to comply with its just nd reasonable requisitions. It is not enough, to be within the visible ark; so was a cursed Ham. Let us not receive the grace of God in vain; but adorn the gospel, by a gospel spirit, and a gospel practice, and walk as children of light. Let us not trample it under our feet, but put our souls under the efficacy of it, and get from it the foretastes of a heavenly and everlasting light. Let us not loiter while the sun shines, lest we be benighted, and bewildered, and misled, and finally miscarry.

Those may, with the strictest propriety, be ranked among the despisers, who dragoon religion into their service, and make it the trumpet of sedition and rebellion. The gospel, is the gospel of peace. It was introduced by angels with Glory to God in the highest, and on earth good will to man. Christ, the author of it, is called the Prince of peace; and it inculcates peace on all its followers. How malignant, then, must that soul be, which would convert it into an engine to irritate, goad, and inflame the passions of men, to strife, blood, and slaughter? When the sacred desk, is converted into a vehicle of scandal, and calumny, and charges predicated on misrepresentation and the most glaring falsehood; this is a prostitution, not only of place, but office, and sinking the ministerial character into that of a public informer. It is a melancholy consideration, that such occurrences should have taken place, as to force from the speaker such observations; but when the poison is openly and widely diffused, it is the duty of every good man to administer an antidote, to counteract the effects of it. Such conduct strikes at the root, and is subversive of a free government, and has a tendency to introduce anarchy and confusion. It likewise flies in the face of divine authority, and sub serves the cause of infidelity; for no truth is more explicitly revealed, than due subordination to government. We will quote a few to corroborate our assertion. Exod. 22. 28. Thou shalt not revile the Gods, nor curse the rulers of thy people. And Rom. 13. 1, 2. Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers. For there is no power but of God: the powers that be are ordained of God. Whosoever resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God; and they that resist shall receive to themselves damnation. Jude calls these disorganizers, v. 8. Filthy dreamers, who defile the flesh, despise dominion, and speak evil of dignities. Can there be a greater prop to infidelity? Did Thomas Paine, with all his frantic ravings against the Christian religion, give it so fatal a stab as these pretended advocates of it, who, in direct opposition to its express commands, defame and pour a torrent of abuse upon our worthy President; a man who, when first inducted into the presidency, was represented, by these his now defamers, as a converted man, and an experimental Christian. But all these puny attempts to sink, will but elevate him the higher, in the esteem of every genuine American; and with dignified composure, and silent contempt, he hears all these unfounded accusations, as the ebullitions of ignorance or of a maniac; and he who has so long withstood the roaring of lions, has nothing to fear from the braying of an ass.

3. Men despise our political privileges, when they use every stratagem to render our government contemptible, and to alienate the affections of their fellow citizens from it. This is to imitate Satan, who would rather reign in hell, than be subordinate in heaven. Never did human wisdom devise so fair a fabric as our Federal Government. Each state united to the other, like the several members of the human body, co-operating for the good of the whole; so that one cannot say, I have no need of you. All are bound by solemn compact, to adhere to each other; for the good of the whole, is the good of each. How malicious! How cruel! How savage! To attempt to mutilate so fair a fabric, and to loose the bond of union, and destroy a system, which, with its increasing years, hath produced increasing prosperity. We grant that our apparent prosperity, has partially been interrupted; but this arose not from any defect in our government, nor in those at the head of it; but from the existing state of the European world, which for a few years past, has been in an uncommon fermentation. Nor could Solomon, had he presided over us, have guarded us against the collisions of the belligerent powers. French ambition, and British cupidity have committed spoliations on our commerce to a vast amount. But must not every impartial person admit, that, to promote a spirit of discord and disunion among ourselves, is not the way to redress, but the sure method to incite them to greater aggressions. Let us frown, indignant, at every attempt to dissolve our federal constitution, however sacred may be their functions; let us regard them as missionaries of him who is the father of lies, and a murderer from the beginning.

When men counteract the means which the wisdom of our Executive devise to assert our rights, redress our wrongs, and maintain our national dignity and honour—or even when they be cold and lukewarm in promoting them, they come within the charge of our text. Such characters may use plausible pleas, to extenuate their conduct—such as the temper of the public mind, the persecutions they shall be exposed to, and the losses they shall sustain; but if these pleas are valid now, they were valid during our revolutionary war; and had the patriots of that day, displayed the same spirit, we should be groaning now in Egyptian bondage. Let such tremble; let them arise from their torpor, lest they subject themselves to the anathema pronounced against some in days of old. See Judges 5. 23. Curse ye Meroz, said the angel of the Lord; curse ye bitterly the inhabitants thereof, because they came not to the help of the Lord, to the help of the Lord against the mighty.

When men turn liberty into licentiousness, and take shelter under the lenity of our law, to degrade and abuse the majesty of the law; this has a tendency to destroy the liberty we enjoy, and lay prostrate in ruin, the fair edifice, which has for thirty years withstood all the rude shocks to which it has been exposed; either by exciting our legislators to lay some restrictions on the press, which at the present teems with so many inflamitory, virulent, and infamous publications, or else reducing us to a state of anarchy. Let me, on this occasion, advise you my hearers, to adhere, inflexibly adhere, to the principles of Republicanism. But at the same time, bear and forbear, with the insults which your principles may expose you to. Remember, our constitution is founded on the right of private judgment, and that principles cannot be destroyed by the force of arms. No; let reason and argument be the only weapons which you will use; and if violence be heard in our land, wasting and destruction within our borders, let them not originate from those who call themselves republicans, and friends of our government; but from those who assume to themselves, the exclusive privilege of being the friends of good order.

Use 1. Let us, to-day, lament over the ruin of lapsed nature, and over the jarring discordant, and destructive effects, which sin has introduced in all our national calamities, under all the pressure of the times, and in the midst of personal sufferings. Let us hear the answer of God to all our murmurings: Thy way, and thy doings, have procured these things unto thee: This is thy wickedness, because it is bitter, because it reacheth unto thy heart. Let us humble ourselves under the mighty hand of God, and by faith in the Redeemer, and genuine repentance, disarm a frowning God of that vengeance which we have demerited at his hands.

2. Let us, like so many Moseses, stand in the gap, and plead with God, that he would spare us, a guilty people, and still indulge us with a continuance of those privileges for which our fathers fought, bled, and died. O, let us not barter them away for present enjoyments, but patiently submit to, and bear a few privations whilst the present contest continues; and though much of our property may be exhausted in the struggle, yet it is better to leave our families the possession of our present privileges, without the possession of a cent, than to leave them millions of dollars, with the entailment of slavery.

3. Let those, who openly express their disaffection to our government, pause, and reflect upon the criminality of their conduct; for God himself bears witness against those sins which disturb society. In these cases, he is pleased to interest himself in a most signal manner, to cool those, who make it their business to overturn the order he hath established for the good of the earth. He doth not so often in this world punish those faults committed immediately against his own honour, as those which put a state into a hurry, and confusion. It is observed, that the most turbulent, seditious persons in a state, come to most violent ends: As Corah, Adonijah, Zimri, Ahitophel draws Absalom’s sword against David and Israel, and the next he twists a halter for himself. Absalom heads a party against his father, and God, by a goodness to Israel, hangs him up, and prevents not its safety, by David’s indulgence, and a future rebellion, had life been spared by the fondness of his father. His providence is more evident in discovering disturbers, and the causes which move them, and in digging the contrivers out of their caverns, and lurking holes. He doth more severely in this world, correct those actions, which unlink the mutual assistance between man and man, and the charitable and kind correspondence he would have kept up.

4. How lost to gratitude, and love of country, must be such of our deluded citizens, who can rejoice in the disasters of those, who are engaged in warfare, against our proud, insulting foe; and are ready to weep at any success which attends our arms. Even the brute beast is attached to the spot which affords it pasture; but they, more brutish, would tear to pieces the foliage of the tree which screens them from the storm, and, unlike the beast, maliciously invite others to join them in blasting our fairest prospects, and laying all in wide ruin and destruction! Is not this too evidently the wish of those among us, who make use of every artifice, and twist and turn all the patriotic measures of our Executive, as being under the control of French influence? Which their own conscience cannot subscribe to, neither do they themselves believe so. But the evil object they have in view, they studiously conceal; and this outcry against French influence, is raised as a mist to blind the eyes of the public, and to sub serve the design of pulling down our present rulers, and to raise themselves on their ruin. Should they succeed in their nefarious plan, what would be the destructive consequence? Why, we soon should see these very same people, who are so clamorous against foreign influence, forming an alliance with Great-Britain, offensive and defensive, which would involve us in the same ruin with herself. Let us, for the truth of this, appeal to stubborn facts. Who is it that justify, and, if they cannot justify, palliate all the insults which we have for ten years past received from that government? If they outrage all laws, moral and divine, by impressing thousands of our gallant seamen; and if, either by bribes, or cruel whippings and floggings, they are forced to enter the service, their advocates extenuate their conduct, by observing, that it is impossible for them to discriminate between our people and their own, as our features and language are so similar. With such reasons and arguments, they justify the cruel wrongs, inflicted on our unhappy countrymen, who are forced to join and assist the common enemy, in their murderous work, and who are perhaps this moment, imbruing their hands in the blood of their nearest friends and dearest relative. These predilections for a government, which is sowing among us the seed of discord, sedition, and treason, and which wishes to tear from us our dearest rights, demonstrates where the bias of their minds tends to. Nor can a word be uttered in their hearing against the British, but what they resent more than they would blasphemy; this speaks volumes, and evidently points to us the object which they have in view. But let them tremble for their conduct. The great mass of our citizens, have too long tasted the sweets of liberty, to exchange it for the gewgaws of monarchy. It is enough for us to will to be free, and maugre all the attempts of anarchists and monarchists, we are free. And let them not suppose, that their misdeeds shall go unpunished. The day of reckoning is fast approaching, when the strong arm of law and justice, will overtake them, and make them sensible that even in a republican government, there is energy enough to crush the guilty.

5. Let not the exertions of the religious inhabitants of England, influence your attachment to the British government, as if the large donations contributed for the support of Missionaries, the distribution of Bibles, and other religious purposes, were the acts of government. These are the generous efforts of its subjects, of individuals, groaning under the pressure of taxes. And how much more would these individuals contribute toward these benevolent purposes, were the demands of government not so numerous! So far is it from true, that the British government is friendly, that it is opposed to the spread of the gospel among the millions in Asia. For, within eight years past, the government of England rejected the application of the Missionary Society to send missionaries to India, to preach the gospel; and which subjected that society to the expense of sending them to New-York, from whence they embarked to the place of their destination. To conclude,

Men brethren, and Fathers,

Let us, today, take a fresh survey of our National, our State, and our personal Blessings, and let us entertain them with a godly jealousy. Let no man under a pretext of liberty, cajole us out of our privileges. With all our calamities, we are comparatively, a happy people. We can boast of what no other people can. The sovereignty is in our own hands. We are not bound, as in France and England, to crouch like beasts of burden to those who goad, and add to the weight of their chains. Our rulers, are our servants, and not our masters. It is by our free suffrages, they have been elevated to their exalted stations; and if they swerve from the principles of liberty, we can destroy their official dignity, and reduce them to the ranks of private citizens, without having recourse to acts of violence. The miseries attending the French revolution, must be yet fresh in your memories; and we hope, and pray, that no aspiring demagogues may be permitted to rise up among us, whereby the proscriptions, assassinations, and murders, of a ferocious Marat, and an ensanguined Robespierre, may pollute and stain our hallowed land of liberty and equality.

And you, my young hearers, read, frequently read, the history of your country. Emulate the deeds of your sires, whose patriotic arms, put to flight the ruffian hordes, which Britain vomited on our shores. O, prove yourselves to be the descendants of those, whose names will shine with luster on the historic page; and should you, like them, be called to avenge your country’s wrongs, prove, that you not only inherit their names, but likewise their courage; that you will not detract from their glory, but maintain with your blood, undiminished, the fair inheritance which they have bequeathed you. And, O, that a double portion of their spirit may rest on you. AMEN, and AMEN.

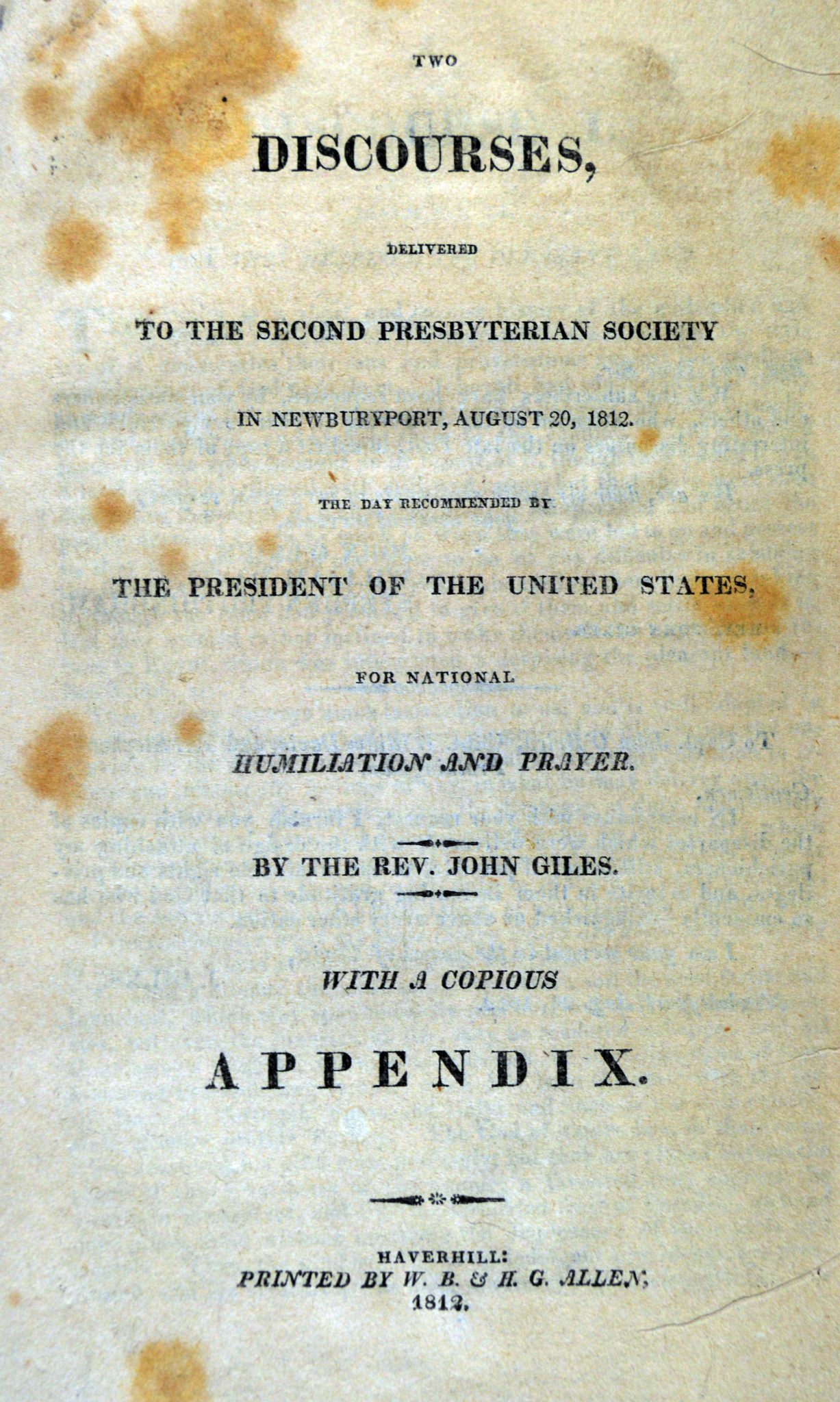

APPENDIX.

To the above discourses we subjorn the following reviews, which have been communicated; in the first of which they are considered merely as literary, and in the second, as political productions:– -to which we add a parallel, exhibiting to the reader not only the pure source from which this reverend gentleman draws the instruction with which he feeds his flock; but the honourable manner in which he does it, by refusing to give the tribute of acknowledgment to whom that tribute is due.

REVIEW I.

THE present is an age of pamphlets. The light which beams from the press, in these days of darkness and blood, seems to overwhelm us with “One tide of glory, one unbounded blaze.” Nor is this light copious only,—it is remarkably intense. The human mind, in the uninterrupted enjoyment of peace, becomes inactive, and fancy ceases to spread her wings, and reposes in torpid slumbers. But, blow the blast of war, and all is life, ardour and strength:—the pen of the erudite is pointed for the combat, and the lips of the eloquent are open to persuade;—genius, by collision with genius, is dazzled with its own scintillations, and reason turns with astonishment from the subject she is pursuing, to admire the profundity of her own researches. The press is the vehicle by which this mental light is communicated from mind to mind; and in the present age, that light appears not only with all the intensity of the solar rays, when condensed by the lens, but with all their variety of colour, when refracted by the prismatic glass, or by the rain drops of the east. Thus we find in the news papers and pamphlets of the present moment, religious light, moral light, political light and various degrees of scientific light.

In a pamphlet now before us, entitled “Two discourses delivered to the Second Presbyterian Society in Newburyport, Aug. 20, 1812, the day recommended by the President of the United States for national humiliation and prayer;—by the Rev. John Giles”—we are pleased to see not only the several kinds of light which we have mentioned, of all which, we presume, there is quantum sufficit, but also a very animating gleam of rhetorical, and a particularly splendid blaze of grammatical light. In the observations we shall make upon these discourses, our object will be principally, to illustrate these unusual traits in productions of this kind, by holding up, to the attention of the reader, passages in which they are more particularly conspicuous,—and that not in the order of their relative merit, but in that of their succession in the book. These beauties meet us on the very threshold:—in the second sentence, the writer, speaking of the Israelites and the Land of promise—says;—“but the spies brought an ill report of it, though they owned it was a land which flowed with milk and honey; but there were such difficulties to possess it which they thought insuperable.”—&c.—

P. 4. “To render a land pleasant its inhabitants must enjoy equal rights and privileges, otherwise it can be pleasant only to a favored few, while the great majority are rendered only objects of misery, through penury and distress; and thus the comforts and blessings of civilized society, he abused, subverted and even prostituted to the most ignoble and basest of purposes.”

Till now we did not know that such and which were correspondent or correlative terms as used in the former of these passages.—And we were at a loss to determine how be abused” was governed either in the infinitive or subjunctive mood, till in the next sentence the clue is given by the luminous proposition that “government in its best state is but a necessary evil.” Here no one can but observe what a flood of light bursts at once upon us.—The reverend republican, since leaving England has contracted such an antipathy to government, of every description, that, not satisfied with emancipating man he generously undertakes to disenthrall even his language from these odious restraints of government.

Again p. 5. “Let us rejoice that we are in the full possession and free exercise of the privilege of selecting from ourselves, men, to be our rulers; and while we give them a compensation for the services which they render the public in their several stations, which is but just and reasonable; for the labourer is worthy of his hire.”

Now some, who do not see things, would suppose there was here a kind of hiatus, as the hearer must be expecting to be told something proper to be done, while, &c. but here the delicate hand of the master is seen, in suffering the imagination of the hearer to have a little play, and fall, by its own efforts, upon the rest of the sentence.

But to proceed: page 10, “The parent, with pallid cheeks, hollow eyes and trembling limbs, arrest not our steps with importunate cries for relief to their helpless infants, &c.—Again “The Israelites forgot God their Saviour, which had done great things in Egypt..”

In old times, when Addison, Johnson and Blair, were at the grammar school, they contracted a habit of making a verb agree with its nominative case, in a number and person, and of making the relative who refer to persons, which to things: and this habit was so fixed upon them that they carried it with them to the last. Even Pope felt himself constrained, by the same illiberal rule, when addressing the same Infinite Being of whom the sacred politician is here speaking, to say

“Thou Great First Cause, least understood,

“Who all my sense” &c.

But in these days, of superior light and liberty, all ideas of concord in a sentence appear as useless and absurd as do those of government. We presume that when this learned gentleman was in England, alias “Babylon,” (vide p. 9,) the Babylonians, being tired of these old fashioned rules, were beginning to get things up in a little better style; and being conversant with the heads of department, or perhaps, more properly with the department of heads, he was the first to receive from authors and orators of the first grade, those emanations of light which he here sheds abroad from himself, as from the radiant point. Not being up to these splendid novelties ourselves, we can but admire in him, the ease with which he declares that “the parent arrest not our “steps” respecting “their helpless infants,” and the dignity with which he invests the Divinity when he makes the Israelites forget God their Saviour which had done great things”—

The specimens heretofore exhibited go, principally, to illustrate the beautiful: but our author occasionally soars to the sublime. The very page from which the two last examples were taken furnishes us with an instance. “But the sense of daily favors, soonest wear out of our minds, which are as great miracles, as any in their own nature, and the products of the same power.”—Here, if our author does not shed his usual light, it is, we presume, not without design. Sublimity is so great an excellence in style, that it is cheaply purchased at the expense of every other. We must not expect, particularly, to have a clear and definite view of the object, nor a full conception of the sentiment that fills our minds with sublime emotions. We must not therefore inquire whether “the sense of daily favors”—the “favours” themselves or “our minds” are the “miracles;”—for the moment we determine, that moment the sublimity vanishes. We could not possibly suppose that sense could be the miracles, because “sense” is singular and “miracles” plural,—were it not that by the magic power of “Liberty and equality” introduced on the last page of the book, our writer has made the singular “sense” equal to the plural “wear” by making them agree as nominative and verb,—of course we do not know how far he may think proper to advance it in dignity: nor do we see any objection, upon principle, to its becoming not only a miracle, but many “miracles.” Between “favours” and “minds,” we think the chance is nearly equal; for as much as is gained by “favours” in relation to the antecedent sentences, so much is gained by “minds,” from its proximity to the relative. This we think is a brilliant instance of the “void obscure”—a bright display of “palpable darkness.”

We pass over the eloquent and gentlemanlike compliments which on pages 11 and 12 he lavishes upon his fellow-labourers in the vineyard of the Lord. But while we admire the generous flow of civility and respect which must be so gratifying to his brethren, the clergy, we must not lose sight of that meek and modest spirit of Christian charity which breathes in every sentence and animates the whole current of his remarks upon them. Our attention however is arrested by the closing sentence of this clerical eulogy, which runs thus—“Let us frown indignant at every attempt to dissolve our federal-constitution, however sacred may be their functions; let us regard them as missionaries of him who is the father of lies and a murderer from the beginning.”—Let those who can, pass this sentence without admiration,—as well as the one next following. “When men counteract the means which the wisdom of our Executive devise to assert our rights”—&c.—These two sentences, must, we presume, be politically correct, and theologically orthodox,—for he who is able to predicate “their functions” of “every attempt”—and then convert “every attempt” into “missionaries” and to make “wisdom” harmonize with “devise” must surely be able to make the rough things of divinity smooth, and the crooked things of the policy straight.

Again, p. 14. “Ahitophel draws Absalom’s sword against David and Israel, and the next he twists an halter for himself.”—The next what? Here again he compliments the reader by suffering the deficiency to be supplied ad libitum by his own imagination.

If we may be indulged yet a little longer, we will endeavour to confine our specimens within as narrow limits as we can, in justice to the subject upon which we have entered. We cannot but dwell a moment upon a very chaste and nervous sentence (p. 15,) which flows in manner and form following, to wit,” “These predilections for a government, which is sowing among us the seed of discord, sedition and treason, and which wishes to tear from us our dearest rights, demonstrates where the bias of their minds tends to.” Here again is displayed that republican hatred of government, which seduces from its nominative the allegiance of the verb—If however the eye is weary with too long contemplating these polished samples of grammatical elegance, each of which might be considered as unique, the ear will undoubtedly be ravished with the rhetorical harmony, and the force of numbers with which this sentence closes.

There are many minor beauties to which we cannot descend, without occupying more space than can be devoted to lucubration’s [intensive study] of this nature: the reader cannot but observe them, on even a hasty perusal—they all go, like those who have brought into notice, to shew a genius improved by science, a taste formed upon the most approved models, a style chastened and elevated, and a fancy whose vagaries have been restrained by the cool dictates of reason. Both the religious and political sentiments we intended to pass over, they are above our humble reach, and must be left to those who are better capable of judging of such “high matters.” If the matter however be equal to the manner, too much cannot be said of it.

There are yet three things which we cannot in justice to the reverend gentleman, neglect to notice. These are his consistency, his modesty and the love he displays towards his native country.

First, his consistency: Our readers must undoubtedly recollect that His Excellency Caleb Strong, who has been raised to the dignity of ruling the free, sovereign and independent people of Massachusetts, in his late proclamation for a State Fast, speaks of Great-Britain, among other things, as the bulwark of the religion we profess. Our republican divine, (may we not say our divine republican) on page 7, speaking also of England, closes his notice of that nation, with these words—“Must it not be duplicity, nay, the very essence of hypocrisy, in any man, to call such a kingdom the bulwark of our religion”—and then goes on (page 12,) to prove from scripture that they who “speak evil of dignities, and curse the rulers of the people, stand at least a chance of “receiving to themselves damnation.”

Of his modesty we have room to say but little; nothing, indeed compared with the subject. It shall however be illustrated in a degree, and faintly shadowed forth, by first recalling to the minds of our readers the recollection of the fact, that during our revolutionary struggle, he was a native inhabitant of the country that strove to strangle America in her cradle, and a subject of the “government with which it is evident the Lord has a controversy;”—and then, while this recollection is fresh in the mind, presenting them one passage from page 8.—

“In our infancy we humbled their pride, and chained to the chariot wheels of our triumph, two of their most celebrated generals; one of which (generals which again) “boasted on the floor of Parliament that with 3000 men he would march in triumph from one end of our Continent to the other. Part of this assertion seemed to be prophetic, for he passed through a section of our Continent to the other. Part of this assertion seemed to be prophetic, for he passed through a section of our Continent, not as a conqueror, but as a crest-fallen prisoner. If we achieved such exploits in our infant state, what shall we not, through providence, be able to do in our manhood.”

Reader, dost thou recollect the story of “we apples”? If thou dost, the modesty of this passage, which is but a small portion of what is exhibited in the whole, cannot be illustrated by more appropriate types and figures.

But we cannot take leave of this very accomplished author, without adverting to the deep and feeling sense, he seems to entertain, of the obligations he owes to his native country: that holy devotion to the land that gave him birth, and infused into his mind, by the liberal education it afforded him, those exalted sentiments, those generous recollections which are poured forth through his whole book.—That profound veneration for the religious establishments, that ardent enthusiasm towards the laws, and that respectful and affectionate zeal for the chief magistrate of England, which form the Alpha and Omega of his discourses cannot but convince every reader that he who is thus filial in his attachments to his mother country, must be unshaken in the grand purpose of ennobling and exalting the character of that which has adopted him.

We cannot, perhaps, close this article better than with the following lines from Churchill,—a man who once dressed in the gown and surplice; which however he left off, after disgracing them and the holy profession to which they were dedicated, by the most wanton practices of debauchery and intemperance; but who at times felt and expressed in his writings, sentiments worthy at least of a layman, tho’ they may not be fully equal, in point of patriotism and elegance, to what now flow from those among us who minister in holy things.

“—–Be England what she will,

With all her faults, she is my country still.—

The love we bear our Country is a root

Which never fails to bring forth golden fruit

‘Tis in the mind an everlasting spring

Of glorious actions, which become a king,

Nor less become a subject; ‘tis a debt,

Which bad men tho’ they pay not, can’t forget;

A duty which the good delight to pay,

And every man can practice every day—-

That spring of love which, in the human mind,

Founded on self, flows narrow and confin’d,

Enlarges as it rolls, and comprehends

The social charities of blood and friends,

Till, smaller streams included, not o’er past,

It rises to our country’s love at last,

And he, with lib’ral and enlarged mind,

Who loves his country, cannot hate mankind.—-

Howe’er our pride may tempt us to conceal

Those passions which we cannot chuse but feel,

There’s a strange, something, which without a brain

Fools feel, and which e’en wise men can’t explain,

Planted in man, to bind him to that earth,

In dearest ties, from whence he drew his birth.

If Honor calls, where’er she points the way

The sons of Honour follow and obey;

If need compels, wherever we are sent

‘Tis want of courage not to be contnt;

But if we have the liberty of choice,

And all depends on our own single voice,

To deem of ev’ry country as the same

Is rank rebellion gainst the lawful claim

Of Nature; and such dull indifference

May be philosophy, but can’t be sense.

REVIEW II.

“What manner o’ thing is your Crocodile?”

THE press has lately teemed with a brace of Sermons from the pen of the Rev. John Giles. These performances are somewhat curious, but they might go down to oblivion quietly, did we not think them a fair specimen of democratic reasoning and declamation; which is a tissue of contradictions, absurdities, vituperations and nonsense.—In a short review of these productions, the writer will not stop to notice the bad grammar with which this work abounds, nor point out the false logic conspicuous in every page; for whoever views these twin born graces of democracy, will see that the Rev. John Giles is as much unacquainted with Isis and Cam, as he is with the constitution of his native country, and abuses the King’s English as freely as he does the Court of St. James, or the Prince Regent.

The text for these Sermons is a pointed and biting sarcasm on the stiff-necked and rebellious Israelites—“Yea they despised the pleasant land,” —and this, by a side-way allusion is meant for those who are not idolaters to his Dagon of power.—From a perusal of this scanty, and distorted picture of national happiness, we do not hesitate to say, that the writer is infested with the political poison drawn from the sewers of Godwin and Paine. There is a peculiar driveling in the pupils of this School, by which we always know them; for they struggle to gain attention by bold assertions,—course, and vulgar epithets; and by quaintness and eccentricity strive to make popular flimsy reasoning, and false sentiments, which are subversive of all order the government.—“Government like dress, is the badge of lost innocence,” says Parson Giles, (and I believe Parson Paine1 said it before him.) This is dazzling and fine, but it is neither witty nor illustrative.

Let us pursue this thought, for a moment, for whether the preacher begot it or purloined it, is all the same. If “Government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence”—the savage, who wears but a rag to cover his nakedness, is nearer primitive purity than President Madison dressed for his levee; and the gentleman himself is more a saint in his every day dress, than when adorned with his flowing canonicals.—The nations of Europe pass in review before the preacher, and all are filled with the abominations of government; and even the shades of departed Greece and Rome are called up, that he might “lay them” with a curse.—But England, poor old England, bears the burden of its blows, here he collects his manly wrath and raves most heroically against Kings and courtly trains. Had the good man been made a Bishop in his native land, never, oh! Never, should we have heard this elegant invective; it would have been lost, we fear in the soft accents of his loyalty to his gracious master.—There are sufferings in all countries, and no doubt many in England, but the difference between this country and that is not so great as he represents it, and if this War continues it will be worse here than in G. Britain.—Is the Gentleman ignorant? This I cannot believe—or did he intend to mislead, when he stated without any explanation, that the King of England receives a million a year for his salary from the people?—Why did he not tell them, that from this sum the whole civil list were paid, and that but a small proportion of it is retained for his own private use? This would have been true, but truth seems not to have been his object.

What Parson Giles has suffered in his native country, that should make him curse his mother so bitterly, is not known with us; but surely he must have suffered some terrible oppression, to justify in any measure, this infuriated resentment.—If common report is not a liar he has, in former times, praised his own country, and spoken with contumely and reproach of the common rabble of these United States, and despised the dear people he now so ardently loves.

When a writer animadverts with manliness, if he is severe, no one has a right to complain; but when malignity calls falsehood and ribaldry to her assistance, we have an unquestionable privilege to despise and condemn.—His attack on the Prince Regent, is mean and false. (“The Prince Regent has by his intemperance and debaucheries, reduced himself to the state of an Idiot.”) That the Regent has been a gay man, is not to be disputed—but, for years past, he has attended the affections of his subjects. Such pitiful slander, such absolute falsehood, such miserable abuse, comes most ungraciously from a preacher of the Gospel of Christ.—All this could be forgiven, but his covert and indirect attack on a man—“in whom there is no guile,” a man whose memory will be fresh, among the virtuous, when the parson, and his sermons are forgotten, cannot and will not be forgiven. It is the attempt, not his success, that we mention, for the Egis of Minerva would sooner have been shattered from the puny strength of an infant arm, than the shaft from the parson’s bow,—however deeply dipped in gall,—have reached one “armed so Strong in honesty.”

The second Sermon commences as follows,,—

“The speaker, in the forenoon, called your attention, to the distinguishing goodness of God, which has exempted us as a people, from the burdens, oppressions, and calamities, under which the nations of Europe groan, and which wring from the inhabitants, the most piercing cries. Our lines are fallen in pleasant places; yea, we have a goodly heritage: but some among us, like Jeshurun of old, have waxed fat and are kicking against the rock of salvation. This leads us, “Second…To exhibit the characters who despise the pleasant land.

“We charge no party, solely, as implicated in this crime; but shall attempt to demonstrate that there are such men among us. And we will, as we proceed in our description, adhere to the criterion laid down by our Saviour—you shall know them by their fruit.

“1. Men may be said to despise it, when they make light of their privileges, either in a natural, moral, or political view.”

The preacher is here extremely confused, at which we are not a little surprised, for nothing is more simple and easy than the lines between natural, moral, and political privileges.—Under the division of natural, he has given us moral, religious and political advantages, and drawn a picture of national prosperity,—even such an one, as meager as it is, we wish to Heaven were accurate; but a prevalence of the principles he professes, has shorn our country of her beams and robbed her of her luster,—dimed the sun of our prosperity, evaporated “the showers,” and blasted “the corn.”—His moral head is a mere farrago [jumble] upon religion, and, in the beginning, discovers a want of liberality that ought not to be found in so great a stickler for religious freedom, who execrates so vehemently the hierarchy of England. He more than intimates that persecution is to be feared from the opponents to his politics, if they should be in power—rest easy, Rev. Sir, your opponents, possessed of power, would forget “your venom and your froth.”

It is extremely amusing to observe some of the inconsistencies in this work.—In one page the preacher appears the most strenuous advocate for the divine rights of Kings; for the doctrine of passive obedience and non-resistance, and calls in the aid of Omnipotence to prove his belief; not remembering that in a few pages before he breathed blasphemy on the ruler of his native land.—This is republicanism fresh from the Schools of France.

How bitterly the gentleman denounces his brothers of the cloth, who venture to lisp a word against the immaculate rulers of our land. No, the clergy must not talk politics,—it is infamous,—it is seditious—according to his creed, while he, forsooth, is belching slander and calumny.

Amidst the descriptions of those who despise the pleasant land, the preacher has contrived to introduce the “Worthy President” of the United States by way of contrast.—A Jupiter on Olympus, surrounded by clouds, and darkness, and attacked by evil spirits—yet firm, and godlike he stands as unmoved at “the roaring of lions,” as at “the braying of an ass,” consulting the good of mortals, notwithstanding their rebellion. He is equal to the war waged against him,—“and with dignified composure and silent contempt, he hears all these unfounded accusations as the ebullitions of ignorance or of a maniac.” This epic flight may not go unrewarded—the “worthy President” has offices and honours to bestow, and money to distribute, and how sweet must this fine strain of panegyric [praise] sound in the ears of the President, who has been so long accustomed to solemn but unpleasant truths from New-England Divines.

The sentiments in these Sermons are so nicely involved, and so charmingly jumbled, that one might as well follow the flight of the raven in the mist, and note all his croaking’s, as to follow the parson in his democratic ramblings through Time and Eternity, over Matter and Mind, War & Peace, Democracy and Federalism—but it is clearly understood that this Minister of Peace is a Friend to War, and calls loudly on his followers to maintain it stoutly.

Patriots, ye who were born on the Atlantic shores, who have once buffeted the storm, and braved the tempest of war, how must you blush to be taught your duty by a foreigner, whose love for you, and your country, surpasses everything, but his hatred for your enemies? How kind it is in him to te4ach you your duty! That lovely and sincere Frenchman Genet was once as kind and courtly, but this ungrateful nation have forgotten him and his services. Genet, it is true, had more talents and ability, but he was not more earnestly devoted to your welfare than the parson,—who will toil in his little sphere with the same holy zeal for his great master, but probably with less success.

It is time to be serious—our all is in jeopardy.—We could continue, at any other time, to treat with playful severity this performance laugh at the author’s folly, and pity his weakness. Our homes, our comforts, our privileges, our rights are all at stake. A weak, false-hearted and pusillanimous government have led us into a miserable war.—A war which has swept Commerce from the Ocean, changed honesty to corruption, and industry to pilfering enterprise. The great sources of wealth are stopped;—the little currents of competency are dried, and scantiness has become absolute want. The voice of complaint is every where heard. The sufferings of the people, must, and will produce a spasm in the body politic, serious and awful to the authors of these evils.—At such a time as this, “every offence should bear its comment,” and folly, virulence, and falsehood, which in prosperous days, might pass with only a sneer, should now be noted with indignation; and wherever found, be pointed at with scorn and derision. It is, and long has been the curse of this country, that we have been taught our rudiments of government from imported patriots, and taken the dregs of Europe for our Masters and Teachers. This country should be an asylum for all nations; but no foreigner should ever have a voice in our Councils.—There are many good men who have come from foreign countries to this, but these men are still, and quietly enjoy the protection of our laws, while a thousand vipers swarm around us, and the moment they are revived by the generous warmth of our breast, sting us to the very soul.

We cannot leave this Rev. Gentleman, without expressing our abhorrence of the following sentiment from his Sermons:—

“Let us wait awhile, and we may live to see the time, wherein it shall not be said by the voice of faith, but by the voice of sense itself, Babylon, (England,) the great is fallen, is fallen!”

This is the most diabolical wish that ever rankled in the heart, or was ever breathed from the lips of a human being. But coming from a minister of the Gospel, in a civilized country, in these New-England States; preached in a place hallowed for religious purposes,—it wears the marks of the beast about it.—Surely the spirit of Napoleon is here; no fiend less than he could have inspired such a thought.

We will now take leave of the Rev. John Giles, and assure him that we should not have noticed these illiterate labours, if such works had not been rare, among our Clergy. The thistle, in Paradise,—if such noxious plants ever grew there, was more noticed—(for the purpose of being avoided,)—than any flower of the valley, or cedar of the hills.

This pleasure we have felt, constantly, near our hearts, in the darkest hour of our political despondency, that men of intellectual wealth, of probity, and principle, in our country were found mostly in the ranks of Federalism. The pulpits (with a few wretched exceptions) have been kept from the tainted air of democracy. The preachers of the everlasting Gospel have seldom failed to oppose the torrent of corruption.

If Federalism be extinguished, the Priest will perish at the Altar, and the Altar be razed to the ground; and the sad fate which the enemies of England wish for her, will be realized in the history of our downfall.—Suffer it not, O God! Stretch thy protecting arm to save us.

Mr. Editor,

For the general conviction of the public respecting the literary character of the Rev. John Giles, I send you a few extracts from the writings of the notorious Thomas Paine, with correspondent ones from the Reverend Divine above mentioned which, to say nothing more, have the appearance of being copied verbatim from Mr. Paine, and palmed upon the world as original.

GILES—published in 1812.

“And here we observe that society in every state is a blessing; but government in its best state is but a necessary evil, in its worst state an intolerable one. For when we suffer or are exposed to the same miseries by a government, which we might expect in a country without government, our calamity is heightened by reflecting that we furnish the means by which we suffer. Government, like dress, is the badge of lost innocence. The palaces of Kings are built on the ruins of the bowers of Paradise.”

Discourse 1st, p. 4.

PAINE—published in 1776.

“Society in every state is a blessing; but Government even in its best state is but a necessary evil, in its worst state an intolerable one. For when we suffer or are exposed to the same miseries by a government which we might expect in a country without government, our calamity is heightened by reflecting that we furnish the means by which we suffer. Government like dress is the badge of lost innocence. The palaces of Kings are built on the ruins of the bowers of Paradise.” Common Sense, p. 1.

“It is a system of mental leveling; It indiscriminately admits every species of character to the same authority. Vice and virtue, ignorance and wisdom, in short every quality good or bad is put on the same level. Kings succeed each other not as rationals; it signifies not what their mental or moral characters are. Such a government appears under all the various characters of childhood, decrepitude and dotage; a thing at nurse, in leading strings or in crutches. It reverses the wholesome order of nature, it occasionally puts children over men, and maniacs to rule the wise.—It requires some talents to be a common mechanic, but to be a king requires only the animal figure of a man, a sort of breathing automation.” Discourse 1st, p. 5.

“It is a system of mental leveling; it indiscriminately admits every species of character to the same authority. Vice and virtue, ignorance and wisdom, in short every quality good or bad is put on the same level. Kings succeed each other not as rationals but as animals. It signifies not what their mental or moral characters are.”

Rights of Man, 2d part, p. 14, published 1792.

“It appears under all the various characters of childhood, decrepitude, dotage; a thing at nurse, in leading strings or in crutches. It reverses the wholesome order of nature. It occasionally puts children over men and the conceits of nonage over wisdom and experience.” p. 15

“It requires some talents to be a common mechanic, but to be a king requires only the animal figure of a man, sort of breathing automaton.” p. 16.

“But I must observe that I am not the personal enemy of kings. No man more heartily wishes than myself to see them all in the happy and honourable state of private individuals. But I am the avowed and open enemy of what is called monarchy, and I am such by principles, which nothing can either alter or corrupt—that is by my attachment to humanity—by the anxiety which I feel within myself for the ease and honour of the human race, by the disgust which I experienced when I observed men directed by children, and governed by brutes—by the horrours, which all the evils that monarchy has spread over the earth excite within my breast—and by those sentiments, which make me shudder at the calamities, the exactions, the wars, and the massacres with which monarchy has crushed mankind.”

p. 5.

“I must also add that that I am not the personal enemy of Kings. Quite the contrary. No man more heartily wishes than myself to see them all in the happy and honorable state of private individuals. But I am the avowed, open and intrepid enemy of what is called monarchy; and I am such, by principles which nothing can either alter or corrupt—by my attachment to humanity—by the anxiety, which I feel within myself, for the dignity and honor of the human race—by the disgust which I experience, when I observed men, directed by children, and governed by brutes—by the horror, which all the evils that monarchy has spread over the earth, excite within my breast—and by those sentiments, which make me shudder at the calamities, the exactions, the wars, and the massacres with which monarchy has crushed mankind.”

Paine’s Letter to Abbe Seyeys, 1791.

“Let us enlarge a little on this sentiment. All religions are in their nature mild and benign, and united with principles of morality. They could not have proselytes at first, by professing any thing which was vicious and persecuting or immoral. How is it then that they lose their native mildness and become morose and intolerant? It proceeds from an alliance between church and state. The inquisition in Spain and Portugal does not proceed from the religion originally professed, but from this mule animal [as one calls it] engendered between church and state. The burnings in Smithfield proceeded from the same heterogenous production; and it was the regeneration of this strange animal afterwards [in the Nation now called the Bulwark of our Religion] which revived rancor and irreligion among the inhabitants there, and which drove the people called dissenters and quakers to this country. Persecution is not an original feature in any religion; but it is the strongly marked picture of all law religions, or religions established by law. Take away the law-establishment, and every religion re-assumes its original benignity: Here in America, a catholic priest is a good citizen, a good character, and a good neighbor; the same may be said of ministers of other denominations, and this proceeds, independent of men, from there being no law-establishment in America.”

Discourse 1st, p. 8.