A black civil rights leader recently told an assembly at Michigan State University that American democracy was only decades old rather than centuries- that not until the 1965 Voting Rights Act when blacks could vote did democracy truly begin. [1]

Such a declaration does not accurately portray the history of black voting in America nor does it honor the thousands of blacks who sacrificed their lives obtaining the right to vote and who exercised that right as long as two centuries ago. In fact, most today are completely unaware that it was not Democrats but was actually Republicans-” like the seven pictured on the front cover-” who not only helped achieve the passage of explicit constitutional voting rights for blacks in 1870 but who also held hundreds of elected offices during the 1800s. [2]

Black Voting in the 1700s

Acknowledgment that blacks voted long before the 1965 Voting Rights Act was provided in the infamous 1856 Dred Scott decision in which a Democratic-controlled US Supreme Court observed that blacks “had no rights which a white man was bound to respect; and that the Negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his benefit.” [3] Non-Democrat Justice Benjamin R. Curtis, one of only two on the Court who dissented in that opinion, provided a lengthy documentary history to show that many blacks in America had often exercised the rights of citizens-” that many at the time of the American Revolution “possessed the franchise of [voters] on equal terms with other citizens.” [4]

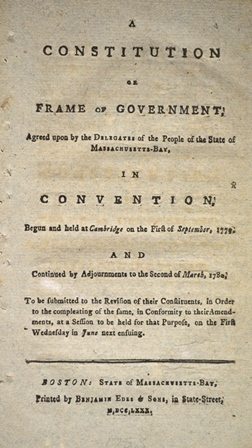

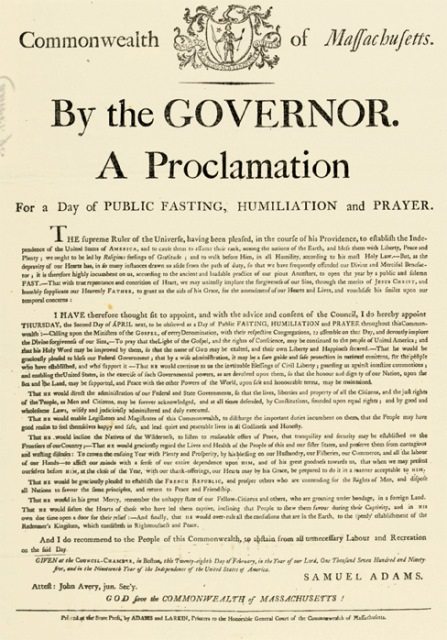

State constitutions protecting voting rights for blacks included those of Delaware (1776), [5] Maryland (1776), [6] New Hampshire (1784), [7] and New York (1777). [8] (Constitution signer Rufus King declared that in New York, “a citizen of color was entitled to all the privileges of a citizen. . . . [and] entitled to vote.”) [9] Pennsylvania also extended such rights in her 1776 constitution, [10] as did Massachusetts in her 1780 constitution. [11] In fact, nearly a century later in 1874, US Rep. Robert Brown Elliott (a black Republican from SC) queried: “When did Massachusetts sully her proud record by placing on her statute-book any law which admitted to the ballot the white man and shut out the black man? She has never done it; she will not do it.” [12]

As a result of these provisions, early American towns such as Baltimore had more blacks than whites voting in elections; [13] and when the proposed US Constitution was placed before citizens in 1787 and 1788, it was ratified by both black and white voters in a number of States. [14]

This is not to imply that all blacks were allowed to vote; free blacks could vote (except in South Carolina) but slaves were not permitted to vote in any State. Yet in many States this was not an issue, for many worked to end slavery during and after the American Revolution. Although Great Britain had prohibited the abolition of slavery in the Colonies before the Revolution, [15] as independent States they were free to end slavery-” as occurred in Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, New Hampshire, and New York. [16] Additionally, blacks in many early States not only had the right to vote but also the right to hold office. [17]

Congressional Actions

In the early years of the Republic, the federal Congress also moved toward ending slavery and thus toward achieving voting rights for all blacks, not just free blacks. For example, in 1789 Congress banned slavery in any federally held territory; in 1794, [18] the exportation of slaves from any State was banned; [19] and in 1808, the importation of slaves into any State was also banned. [20] In fact, more progress was made to end slavery and achieve civil rights for blacks in America at that time than was made in any other nation in the world. [21]

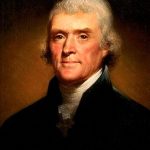

In 1820, however, following the death of most of the Founding Fathers, a new generation of leaders in Congress halted and reversed this early progress through acts such as the Missouri Compromise, which permitted the admission of new slave-holding States. [22] This policy was loudly lamented and strenuously opposed by the few Founders remaining alive. Elias Boudinot-” a president of Congress during the Revolution-” warned that this new direction by Congress would bring “an end to the happiness of the United States.” [23] A frail John Adams feared that lifting the slavery prohibition would destroy America; [24] and an elderly Jefferson was appalled at the proposal, declaring, “In the gloomiest moment of the Revolutionary War, I never had any apprehensions equal to what I feel from this source.” [25] Congress also enacted the Fugitive Slave Law allowing southern slavers to go North and kidnap blacks on the spurious claim that they were runaway slaves [26] and then passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, allowing slavery into what is now Colorado, Wyoming, Montana, Idaho, North Dakota, South Dakota, Kansas, and Nebraska. [27]

This new anti-civil rights attitude in Congress was also reflected in many of the Southern and Mid-Atlantic States. For example, in 1835 North Carolina reversed its policies and limited voting to whites only, [28] as also occurred in Maryland in 1809. [29]

Political Parties

The Democratic Party had become the dominant political party in America in the 1820s, [30] and in May 1854, in response to the strong pro-slavery positions of the Democrats, several anti-slavery Members of Congress formed an anti-slavery party-” the Republican Party. [31] It was founded upon the principles of equality originally set forth in the governing documents of the Republic. In an 1865 publication documenting the history of black voting rights, Philadelphia attorney John Hancock confirmed that the Declaration of Independence set forth “equal rights to all. It contains not a word nor a clause regarding color. Nor is there any provision of the kind to be found in the Constitution of the United States.” [32]

The original Republican platform in 1856 had only nine planks-” six of which were dedicated to ending slavery and securing equal rights for African-Americans. [33] The Democratic platform of that year took an opposite position and defended slavery, even warning that “all efforts of the abolitionists [those opposed to slavery]. . . are calculated to lead to the most alarming and dangerous consequences and . . . diminish the happiness of the people and endanger the stability and permanency of the Union.” [34] The next Democratic platform (1860) endorsed both the Fugitive Slave Law and the Dred Scott decision; [35] Democrats even distributed copies of the Dred Scott ruling to justify their anti-black positions. [36]

Specific Constitutional Rights for African-Americans

When Abraham Lincoln was elected the first Republican President in 1861 (along with the first ever Republican Congress), southern pro-slavery Democrats saw the handwriting on the wall. They left the Union and took their States with them, forming a brand new nation: the Confederate States of America, and their followers became known as Rebels. During the War, Lincoln implemented the first anti-slavery measures since the early Republic: in 1862, he abolished slavery in Washington, DC; [37] in 1863, he issued the Emancipation Proclamation, ordering slaves to be freed in southern States that had not already done so; [38] in 1864, he signed several early civil rights bills; [39] etc. After the war ended in 1865, the Republican Congress passed the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery and the 14th Amendment providing full civil rights for all blacks, thus fulfilling the original promise of the Declaration of Independence.

Most southern States ignored these new Amendments. [40] Congress therefore insisted that the southern States ratify and implement these Amendments before they could be readmitted into the United States. [41]

Until their readmission, the civil rights of the Rebels in the South-” including their right to vote in elections-” were suspended. [42] The Constitution authorizes that certain civil rights may be suspended “in cases of rebellion” or when “the public safety may require it” (Art. I, Sec. 9, cl. 2). In fact, because the Rebels had taken up arms against their own nation-” an act of treason according to the Constitution (“Treason against the United States shall consist only in levying war against them . . .” Art. III, Sec. 3, cl. 1), they could have been executed (Art. III, Sec. 3, cl. 2). Instead, amnesty was granted to the Rebels if they took an oath of fidelity to the United States, which most eventually did. (Regrettably, after their readmission, and after Democrats regained the State legislatures from Republicans, those States worked aggressively to circumvent the 14th Amendment in violation of the pledge [43] they had taken.)

Because the Rebels (who had almost exclusively been Democrats) were not allowed to vote in the early parts of Reconstruction, Republicans became the political majority in the South; and since nearly every African-American was a Republican and could now vote, most southern legislatures-” at least for a few years-” became Republican and included many black legislators. In Texas, 42 blacks were elected to the State Legislature, [44] 50 to the South Carolina Legislature, [45] 127 to Louisiana’s, [46] 99 to Alabama’s, [47] etc.-” all as Republicans. These Republican legislatures moved quickly to protect voting rights for blacks, prohibit segregation, establish public education, and open public transportation, State police, juries, and other institutions to blacks. [48] (It is noteworthy that the blacks serving both in the federal and State legislatures during that time forgivingly voted for amnesty for the Rebels. [49])

During the time when most southern Democrats had not yet signed the oath of fidelity to the United States and therefore could not vote, they still found ways to intimidate and keep blacks from voting. For example, in 1865-1866, the Ku Klux Klan was formed by Democrats to overthrow Republicans and pave the way for Democrats to regain control [50]-” as when Democrats attacked the State Republican Convention in Louisiana in 1866, killing 40 blacks, 20 whites, and wounding 150 others. [51] In addition to the use of force, southern Democrats also relied on absurd technicalities to limit blacks. In Georgia, 28 black legislators were elected as Republicans, but Democratic officials decided that even though blacks had the right to vote in Georgia, they did not have the right to hold office; the 28 black members were therefore expelled. [52]

Because of such blatant attempts to nullify the guarantees of the 14th Amendment, the Republican Congress passed the 15th Amendment to give explicit voting rights to African-Americans. Significantly, not one of the 56 Democrats serving in Congress at that time voted for the 15th Amendment. [53]

Democratic Efforts to Limit Voting Rights for Blacks

During Reconstruction (1865-1877), Republicans passed four federal civil rights bills to protect the rights of African-Americans, the fourth being passed in 1875. [54] It was nearly a century before the next civil rights bill was passed, because in 1876 Democrats regained partial control of Congress and successfully blocked further progress. As Democrats regained control of the legislatures in southern States, they began to repeal State civil rights protections and to abrogate existing federal civil rights laws. As African-American US Rep. John Roy Lynch (MS) noted, “The opposition to civil rights in the South is confined almost exclusively to States under democratic control . . .” [55]

Devious and cunning methods were required to circumvent the explicit voting protections of the 14th and 15th Amendments, and southern Democrats implemented nearly a dozen separate devices to prevent blacks from voting, including:

-

Poll taxes

-

Literacy tests

-

“Grandfather” clauses

-

Suppressive election procedures

-

Black codes and enforced segregation

-

Bizarre gerrymandering

-

White-only primaries

-

Physical intimidation and violence

-

Restrictive eligibility requirements

-

Rewriting of State constitutions

1. The poll tax

The poll tax was a fee paid by a voter before he could vote. The fee was high enough that most poor were unable to pay the tax and therefore unable to vote. Although the poll tax affected both whites and blacks, it was disproportionately hard on blacks who were just emerging from slavery, many of whom had not yet established an independent means of living. A poll tax was first proposed in Texas in 1874, right after Democrats reclaimed power from the Republicans, [56] but it was North Carolina in 1876 that became the first State to enact a poll tax, [57] and other southern States quickly followed. [58]

2. Literacy tests

Literacy tests required a voter to demonstrate a certain level of learning proficiency before he could vote. In some cases, the test was 20 pages long for blacks, and those administering the tests were white Democrats who nearly always ruled that blacks were illiterate. In Alabama, the test included questions such as, “Where do presidential electors cast ballots for president?” “Name the rights a person has after he has been indicted by a grand jury.” [59] Democrats required blacks to have an above average education before they could vote but then simultaneously opposed black education and even worked with the Ku Klux Klan to burn down schools attended by blacks. [60] Clearly, they did not intend for blacks to vote.

3. “Grandfather” clauses

“Grandfather” clauses were laws passed by Democratic legislatures allowing an individual to vote if his father or grandfather had been registered to vote prior to the passage of the 15th Amendment. [61] Since voting in the South prior to the 15th Amendment was almost completely by whites, this law ensured that poor and illiterate whites, but not blacks, could vote.

4. Suppressive election procedures

Some election procedures (such as “multiple ballots”) were intentionally made complex and misleading. For example, a Republican voter might be required to cast a ballot in up to eight separate locations-” or sometimes to cast a vote for each Republican on the ballot at a separate location-” before the ballot would be counted. Democratic officials, however, often failed to inform black voters of this complicated procedure and their ballots were therefore disqualified. [62]

5. Black codes and enforced segregation

Black Codes (later called Jim Crow laws) restricted the freedoms and economic opportunities of blacks. For example, in the four years from 1865-1869, southern Democrats passed “Black Codes” to prohibit blacks from voting, holding office, owning property, entering towns without permission, serving on juries, or racially intermarrying. [63]

National observers at that time concluded that the South was simply trying to institute a new form of slavery through these Black Codes. [64] This tactic was obvious to African-Americans, thus causing black US Rep. Joseph H. Rainey (Republican from SC) to quip: “I can only say that we love freedom more-” vastly more-” than slavery; consequently we hope to keep clear of the Democrats!” [65]

Southern Democrats went well beyond Black Codes, however, and also imposed forced racial segregation. In 1875, Tennessee became the first State to do so, [66] and by 1890 several other southern States had followed. [67] As a result, schools, hospitals, public transportation, restaurants, etc., became segregated. (Even though the Republican Congress had already passed laws banning segregation, the US Supreme Court struck down those anti-segregation laws in a series of decisions in the 1870s and 1880s. [68])

6. Bizarre gerrymandering

Once the Democrats regained State legislatures at the end of Reconstruction, they began to redraw election lines to make it impossible for Republicans to be elected, thereby preventing blacks from being elected. [69] For example, although many blacks were elected as Republicans in Texas during Reconstruction, when the last African-American left the State House in 1897, none was elected (either as a Republican or a Democrat) for the next 70 years until federal courts ordered a change in the way Texas Democrats drew voting lines. [70] Furthermore, although Republicans had been an overwhelming majority in the State legislature during Reconstruction, after Democrats redrew election lines, for several decades there were never more than two Republicans serving in the House nor one in the Senate. [71] This pattern was typical in other southern States as well.

7. White-only primaries

Another way Democrats could keep blacks from being elected was by enacting Democratic Party policies prohibiting blacks from voting in their primaries. When Texas later codified this policy into State law, the US Supreme Court struck down that Texas law in 1927, [72] but not the party policies. The Democratic Parties in Georgia, [73] Louisiana, [74] Florida, [75] Mississippi, [76] South Carolina, [77] etc., therefore continued their reliance on white-only primaries. Because Democrats solidly controlled every level of government in the South (often called the “solid Democratic South” [78]), this policy had the same effect as a State law and again ensured that no black would be elected. In 1935, the Supreme Court upheld this Democratic policy [79] but then reversed itself and finally struck it down in 1944. [80]

8. Physical intimidation and violence

In 1871, black US Rep. Robert Brown Elliott (Republican from SC) observed that: “the declared purpose [of the Democratic party is] to defeat the ballot with the bullet and other coercive means. . . . The white Republican of the South is also hunted down and murdered or scourged for his opinion’s sake, and during the past two years more than six hundred loyal [Republican] men of both races have perished in my State alone.” [81] Elliott’s term “coercive means” accurately described the lynchings as well as the cross burnings, church burnings, incarceration on trumped-up charges, beatings, rape, murder, etc.

The Ku Klux Klan was a leader in this form of violent intimidation by Democrats. As African-American US Rep. James T. Rapier (Republican from al) explained in 1874, Democrats “were hunting me down as the partridge on the mount, night and day, with their Ku Klux Klan, simply because I was a Republican and refused to bow at the foot of their Baal.” [82]

Of all forms of violent intimidation, lynchings were by far the most effective. Between 1882 and 1964, 4,743 persons were lynched-” 3,446 blacks and 1,297 whites. [83] Why were so many more blacks lynched than whites? According to African-American Rep. John R. Lynch (Republican from SC), “More colored than white men are thus persecuted simply because they constitute in larger numbers the opposition to the Democratic Party.” [84]

Republicans often led the effort to pass federal anti-lynching laws, [85] but Democrats successfully blocked every anti-lynching bill. For example, in 1921, Republican Rep. Leonidas Dyer (MO) introduced a federal anti-lynching bill in Congress, but Democrats in the Senate killed it. [86] The NAACP reported on December 17, 1921, that: “since the introduction of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill in Congress on April 11, 1921, there have been 28 persons murdered by lynchings in the United States.” [87] Although some Democrats introduced anti-lynching bills across the decades, their Democratic leaders killed every effort and Congress never did pass an anti-lynching bill. [88]

9. Restrictive eligibility requirements

Election policies designed to limit black voting included requirements that a voter must reside in a state for two years, his county for one year, and his ward or precinct for six months before he could vote. [89] This requirement especially limited the effect of workers seeking employment-” often blacks. After the poll tax was abolished, some States, still trying to achieve the same effect, enacted annual registration fees for voters. The lower courts struck down such fees in 1971; [90] in 1972 the Supreme Court struck down the excessive filing fees established by Democratic legislatures; [91] these fees were designed to prevent what the Supreme Court had termed the “less affluent segment of the community” [92] from participating as candidates.

10. Rewriting of State constitutions

As a part of Reconstruction, most southern States had been required to rewrite their State constitutions to add full civil rights protections. [93] However, less than two decades later, many States revised their constitutions to remove those clauses. For example, in 1868 North Carolina had rewritten its constitution to include civil rights, [94] but in 1876 it amended its constitution to exclude most blacks from voting. [95] Over the next two decades, Democrats in Mississippi, [96] South Carolina, [97] Louisiana, [98] Florida, [99] Alabama, [100] and Virginia [101] also altered their constitutions or passed laws to negate many of the rights given to blacks during Reconstruction.

11. Other requirements

Other restrictions used by Democrats to keep blacks from voting included property ownership requirements. For example, in Alabama in 1901, a voter was required to own land or property worth at least $300 before he could vote [102] (today that would equate to more than $6,500. [103]) Some States would withhold voting rights for the “commission” of a crime-” not for a serious crime or a felony but rather for violating any of a long list of petty offenses (unemployed blacks or those looking for work were often charged with vagrancy, resulting in a loss of their voting rights). [104]

An Historical Sidenote

Current writers and texts addressing the post-Civil War period often present an incomplete portrayal of that era. For example, africana.com notes: “Southerners established whites-only voting in party primaries . . . or gerrymandered electoral districts, thus diluting the strength of black voters.” [105] Although it is true that both whites and southerners were the overwhelming source of difficulties for African-Americans, it was just one type of southern whites that caused the problems: southern racist whites. There was another type of southern whites: the non-racist whites, many of whom suffered great persecutions and even loss of life for supporting blacks. These whites are often unrecognized or unacknowledged in black history and are wrongly grouped with racist whites through the use of the overly broad terms such as “southerners” or “whites.” To make an accurate portrayal of black history, a distinction must be made between types of whites.

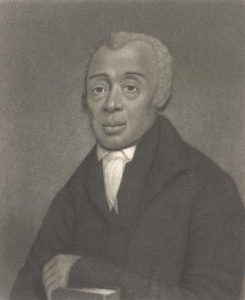

For example, the Rev. Richard Allen (1760-1831), a founder of the AME church in America, suffered many injuries at the hands of “whites”: he was a slave, his mother and brothers were sold separately and his family was split by his master, Allen was opposed by prominent Gospel ministers, etc. Yet Allen understood that only some whites were hostile. In fact, in his own memoirs, Allen openly acknowledges whites who helped him. For example, Allen writes to other blacks: “I hope the name of Dr. Benjamin Rush [a white signer of the Declaration] and Robert Ralston [a white wealthy merchant] will never be forgotten among us. They were the first two gentlemen who espoused the cause of the oppressed and aided us in building the house of the Lord for the poor Africans to worship in.” [106] Allen also notes that in 1784 when he started his first church in Philadelphia, “there were but few colored people in the neighborhood-” the most of my congregation was white.” [107] Such positive portrayals of black/white relations are too often missing from black history pieces today; instead, “whites” are described as oppressors. Some were; some were not.

Another illustration is provided by the passage of the 13th and 14th Amendments. Constitutional amendments must be passed by a margin of two-thirds in Congress and ratified by three-fourths of the States. Those Amendments abolishing slavery and providing civil rights and voting rights for African-Americans were passed by two-thirds of the white men in Congress and by white men in the legislature of three-fourths of the States-” an overwhelming majority of these white men were Republicans and were not racists. (Among the literally hundreds of whites voting for these amendments were two African-American Republicans elected in Massachusetts in 1866. [108])

Therefore, the africana.com quote would be much more historically correct-” although more politically incorrect-” were it to read: “Democratic legislatures in the South [instead of just “southerners”] established whites-only voting in party primaries . . . ” This weakness of distinction is typical of far too many black history writings addressing the post-Reconstruction era.

An Obvious Purpose

It is clear that many southern Democrats despised blacks and Republicans and used every possible means to keep them from power. This hostility was evident in the numerous devices they used-” including violence. In fact, after examining the abundant evidence, Republican US Sen. Roscoe Conkling (nominated as a US Supreme Court Justice in 1882) concluded that the Democratic Party was determined to exterminate blacks in those States where Democratic supremacy was threatened. [109]

The Democrats’ hostility was evident not only in their actions but also in the words they used to describe blacks and Republicans. Democrats applied epithets that were at that time considered base, vulgar, and derogatory-” terms such as “scalawags” (those in the South who had opposed succession) [110] or “radicals” (early Republicans were considered radical because their party was bi-racial and because they allowed blacks to vote and participate in the political process). [111]

Clearly, because Republicans embraced and welcomed blacks as equals, Democrats abhorred and bitterly opposed them. As black US Rep. Richard H. Cain (Republican from SC) explained in 1875: “The bad blood of the South comes because the Negroes are Republicans. If they would only cease to be Republicans and vote the straight-out Democratic ticket there would be no trouble. Then the bad blood would sink entirely out of sight.” [112] Many Democrats today-” including many black Democrats-” have picked up the Democrats’ long-standing hatred for Republicans without understanding its origins. They often blame that generations-long contempt on issues other than the anti-black, anti-Republican sentiments that shaped their Party, but history is clear.

Fighting the Constitution

Decades after the passage of the 14th and 15th Amendments, many Democrats still steadfastly opposed those protections. In 1900, Democrat US Sen. Ben Tillman (SC) declared: “We made up our minds that the 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution were themselves null and void; that the [civil rights] acts of Congress . . . were null and void; that oaths required by such laws were null and void.” [113] Democrats such as Rep. W. Bourke Cockran (NY), Sen. John Tyler Morgan (AL), Sen. Samuel McEnery (LA), and others agreed with this position and were among the Democrats seeking a repeal of the 15th Amendment (voting rights for African-Americans). [114] In fact, Sen. McEnery even declared: “I believe . . . that not a single southern Senator would object to such a move” [115] (of the 22 southern Senators, 20 were Democrats [116]).

Effect on Black Voting

Unrelenting efforts by Democrats to suppress black voting were successful. Eventually, in Selma, Alabama, the voting rolls were 99 percent white and 1 percent black even though there were more black residents than whites in that city; [117] and in Birmingham-” a city with 18,000 blacks-” only 30 of them were eligible to vote. [118] Black voters in Alabama and Florida were reduced by nearly 90 percent, [119] and in Texas from 100,000 to only 5,000. [120] By the 1940s, only 5 percent of blacks in the south were registered to vote. [121]

More Recent Civil Rights Efforts

In the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, a few Democratic leaders began to oppose their own party’s policies against blacks. Democratic President Harry S. Truman from Missouri was perhaps the first and most vocal national Democratic leader to advocate strong civil rights protections, [122] yet his party rejected his efforts. [123] Reformers such as Truman learned that it was a difficult task for rank-and-file Democrats to reshape their long-held views on race.

In fact, in 1924 when Texas Democratic candidate for Governor, Ma Ferguson, ran against the Democratic Ku Klux Klan candidate in the primary, it cost her the widespread support of the Texas Democratic Party. [124] Democrat Franklin Roosevelt understood his Party, however, and in his 1932 race he made subtle overtures to blacks but avoided making any overt civil rights promises. FDR was so unsuccessful in this approach that his Republican opponent, Herbert Hoover, received over 75 percent of the black vote in that election. [125]

Unlike FDR, Harry Truman worked boldly and openly to change his party. In 1946, he became the first modern President to institute a comprehensive review of race relations and, not surprisingly, faced strenuous opposition from within his own party. In fact, Democratic Sen. Theodore Bilbo (MS) admonished every “red blooded Anglo Saxon man in Mississippi to resort to any means” to keep blacks from voting. [126] Nonetheless, Truman pushed forward and introduced an aggressive civil rights legislative package that included an anti-lynching law, an anti-poll tax law, desegregation of the military, etc., but his own party killed all of his proposals. [127]

Southern Democratic Governors, denouncing Truman’s proposals, met in Florida and proposed what they called a “southern conference of true Democrats” to plan their strategy. [128] That summer at the Democratic National Convention when Truman placed strong civil rights language in the national Democratic platform, a walkout of southern delegates resulted. Southern Democrats then formed the Dixiecrat Party and ran South Carolina Gov. Strom Thurmond as their candidate for President. [129] (It was concerning this 1948 presidential bid by Thurmond that Republican Sen. Trent Lott (MS) uttered his disgraceful comments [130] that made national news.) Thurmond’s bid was unsuccessful; he later had a change of heart on civil rights and in 1964 left the Democratic Party. In 1971, as a Republican US Senator, Thurmond became the first southern Senator to hire a black in his senatorial office. [131]

In 1954, additional civil rights progress was made when the US Supreme Court rendered its Brown v. Board of Education decision, [132] integrating public schools and ending segregation. (Significantly, the Court was only reversing its own position taken nearly sixty years earlier in the Plessy v. Ferguson decision that upheld segregation laws enacted by Democratic State legislatures.)

In 1957, and then again in 1960, Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower made bold civil rights proposals to increase black voting rights and protections. [133] Since Congress was solidly in the hands of the Democrats, they cut the heart out of his bills before passing weak, watered-down versions of his proposals. [134] Nevertheless, to focus national attention upon the plight of blacks, Eisenhower started a civil rights commission and was the first President to appoint a black to an executive position in the White House. [135]

In 1963, following the Birmingham riots, Democratic President John F. Kennedy proposed a strong civil rights bill. Its language was taken from the wording of Eisenhower’s original civil rights bill (before it was gutted by Democrats) and from proposals made by Eisenhower’s civil rights commission. [136] Kennedy’s tragic assassination halted his bill.

In 1964, the 24th Amendment was added to the Constitution, abolishing the poll tax. Significantly, on five previous occasions the House passed a ban on the poll tax but Senate Democrats had killed the bills each time. [137] As early as 1949 (as part of Truman’s proposed civil rights package), Democratic Sen. Spessard Holland (FL) introduced a constitutional amendment to end poll taxes, but it was 1962 before it was approved by the Senate. [138] Significantly, 91 percent of the Republicans in Congress voted to end the poll tax but only 71 percent of the Democrats did so; and in the Senate, of the 16 Senators who opposed the 24th Amendment, 15 were Democrats. [139] (The 24th Amendment banned poll taxes only for federal elections; in 1966, the US Supreme Court struck down poll taxes for all elections, including local and State. [140])

In 1964, Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson picked up the civil rights bill introduced by President Kennedy. However, even though Democrats held almost two-thirds of the seats in Congress at that time, Johnson could not garner sufficient votes from within his own party to pass the bill. (Johnson needed 269 votes from his Party to achieve passage but could garner the support of only 198 of the 315 Democrats in Congress. [141]) Johnson therefore worked with Republicans to achieve the passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Bill, followed by the 1965 Voting Rights Act. (The 1965 Voting Rights Act by Johnson was a resurrection of Eisenhower’s original language before it had been killed by Democrats. When it was finally approved under Johnson, of the 18 Senators who opposed the Voting Rights Act, 17 were Democrats. In fact, 97 percent of Republican Senators voted for the Act. [142])

The 1965 Voting Rights Act banned literacy tests and authorized the federal government to oversee voter registration and elections in counties that had used voter eligibility tests. Within a year, 450,000 new southern blacks successfully registered to vote; [143] and voter registration of African-Americans in Mississippi rose from only 5 percent in 1960 to 60 percent by 1968. [144]

The 1965 Voting Rights Act opened opportunities for African-Americans that they had not enjoyed since Republicans had been in power a century before; the laws and policies long enforced by southern Democratic legislatures had finally come to an end. As a result, the number of blacks serving in federal and State legislatures rose from 2 in 1965 to 160 in 1990. [145]

Controversies and Successes

In recent years, much national media coverage has focused on allegations of election fraud in Dade County and West Palm Beach, Florida; St. Louis, Missouri; Michigan (the buying of votes); New Mexico (the destruction of thousands of uncounted ballots); etc. Significantly, each one of these incidents occurred in an area that was overwhelmingly Democratic and where the elections had been administered by Democratic election officials. The fact that such problems occur in areas under Democratic rather than Republican control might surprise many today, but it would not have surprised African-Americans a century ago.

In 1875, African-American US Rep. Joseph H. Rainey (Republican from SC) declared: “We intend to continue to vote so long as the government gives us the right and necessary protection; and I know that right accorded to us now will never be withheld in the future if left to the Republican Party.” [146] In fact, on the floor of Congress, Rainey told Democrats: “Your votes, your actions, and the constant cultivation of your cherished prejudices prove to the Negroes of the entire country that the Democrats are in opposition to them, and if they (the Democrats) could have [their way], our race would have no foothold here. . . . The Democratic Party may woo us, they may court us and try to get us to worship at their shrine, but I will tell the gentleman that we are Republicans by instinct, and we will be Republicans so long as God will allow our proper senses to hold sway over us.” [147]

The original philosophies and actions of both major parties are vividly documented in history but are largely unreported today. And while there has been good and bad on both sides, a general pattern is clearly established: African-Americans made their most significant gains as Republicans. Even today many of those patterns still remain. It is significant that black Republican US Rep. JC Watts (OK) chaired the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia in 2000. Watts was the third African-American to chair a National Republican Convention (the first was US Rep. John Roy Lynch (MS) in 1884 and then US Sen. Edward Brooke (MA) in 1968); [148] however, no African-American has ever chaired, or even co-chaired, a Democratic National Convention. Similarly, in the 130 years that Democrats controlled Texas, only 4 minority individuals served Statewide; in the 8 years that Republicans have controlled the State, 6 minority individuals already have served Statewide. In fact, Texas just elected three African-Americans to statewide office-” all as Republicans, apparently becoming the first State in America’s history to achieve this distinction. Furthermore, Maryland and Ohio each just elected black Lt. Governors-” both as Republicans.

An important point is illustrated by these recent elections (and by scores before them): in Democratic-controlled States, rarely are African-Americans elected statewide (with the exception of US Sen. Carol Moseley-Braun (IL, 1992-1998)); and African-American Democratic Representatives to Congress usually are elected only from minority districts (districts with a majority of minority voters). Minority Republicans, on the other hand, are elected statewide in Republican States, or in congressional districts with large white majorities. [149]

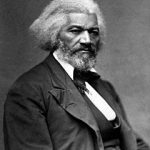

Perhaps this explains why African-American abolitionist Frederick Douglass a century ago reminded blacks: “The Republican Party is the ship, all else is the sea.” [150] The history of African-American voting rights in America proves Douglass was right.

[For more information on the struggle for African American Civil Rights see our Setting the Record Straight resource (in DVD, VHS, and Book format); we have also cataloged our Black History resources here]

Endnotes

[1] The Washington Times online, Steve Miller, “Jackson dismisses Founding Fathers,” September 16, 2002 (at https://www.wa shtimes.com/national/20020916-78725174.htm).

[2] Stanford University online, Peter Kolchin, “Reconstruction,” 1997 (at https://www.stanford.edu/~paherman/reconstruction.htm).

[3] Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393, 407 (1856).

[4] Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393, 573 (1856), Curtis, J. (dissenting).

[5] The Constitutions of the Several Independent States of America (Boston: Norman and Bowen, 1785), p. 92, 1776 Delaware Constitution, “Declaration of Rights,” #6.

[6] Constitutions (1785), p. 104, 1776 Maryland Constitution, “Declaration of Rights,” #5.

[7] Constitutions (1785), p. 5, 1784 New Hampshire Constitution, “Bill of Rights,” #11.

[8] Constitutions (1785), p. 58, 1777 New York Constitution, “Declaration of Rights,” #7.

[9] Rufus King, The Life and Correspondence of Rufus King, Charles R. King, editor (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1900), p. 404.

[10] Constitutions (1785), p. 78, 1776 Pennsylvania Constitution, “Declaration of Rights,” #7.

[11] Constitutions (1785), p. 8, 1780 Massachusetts Constitution, “Declaration of Rights,” #9.

[12] Carter G. Woodson, Negro Orators and Their Orations (Washington, DC: The Associated Publishers, Inc., 1925), p. 310, Rep. Robert Brown Elliott from his speech on the Civil Rights Bill on January 6, 1874.

[13] John Hancock, Essays on the Elective Franchise; or, Who Has the Right to Vote? (Philadelphia: Merrihew & Son, 1865), pp. 22-23.

[14] Hancock, Essays on the Elective Franchise, p. 27.

[15] Benson Lossing, Harpers’ Popular Cyclopedia, pp.1299-1300; W.O. Blake, History of Slavery and the Slave Trade, p. 177; Benjamin Franklin, The Works of Benjamin Franklin, Jared Sparks, editor (1839), Vol. VIII, p. 42, to the Rev. Dean Woodward on April 10, 1773; Frank Moore, Materials for History Printed From Original Manuscripts, the Correspondence of Henry Laurens of South Carolina (New York: Zenger Club, 1861), p. 20, to John Laurens on August 14, 1776; Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Albert Ellery Bergh, editor (Washington, DC: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Assoc., 1903), Vol. I, p. 34.

[16] Thomas R. R. Cobb, An Inquiry into the Law of Negro Slavery in the United States of America (Philadelphia: T. & T.W. Johnson & Co., 1858), pp. 171-172; see also The Public Laws of the State of Rhode-Island and Providence Plantations, as revised by a Committee, and finally enacted by the Honorable General Assembly, at their Session in January, 1798 (Providence: Carter and Wilkinson, 1798), pp. 607-611; see also The Public Statute Laws of the State of Connecticut. Book 1. Published by Authority of the General Assembly (Hartford: Hudson and Goodwin, 1808), pp. 623-626; see also Laws of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, From the Fourteenth Day of October, One Thousand Seven Hundred, to the Twentieth Day of March One Thousand Eight Hundred and Ten. Published by Authority of the Legislature (Philadelphia: Jon Bioren, 1810), Vol. 1, pp. 492-497.

[17] Constitutions (1785), p. 5, 1784 New Hampshire Constitution, “Declaration of Rights,” #11; p. 8, 1780 Massachusetts Constitution, #9; p. 78, 1776 Pennsylvania Constitution, #7.

[18] Debates and Proceedings in the Congress of the United States (Washington, DC: Gales and Seaton, 1834), Vol. II, p. 2215, 1789, “An act to provide for the government of the Territory northwest of the river Ohio”; see also The Constitutions of the United States of America (Trenton: William and David Robinson, 1813), p. 366, “Northwest Ordinance,” Article #6.

[19] Debates and Proceedings (1849), p. 1425, “An act to prohibit the carrying on the slave-trade from the United States to any foreign place or country” in 1794.

[20] Debates and Proceedings (1849), p. 1266, “An act to prohibit the importation of slaves into any port or place within the jurisdiction of the United States” in 1807.

[21] Cobb, An Inquiry into the Law of Negro Slavery, pp. 153, 163, 169.

[22] Debates and Proceedings (1849), pp. 2555, 2559, “An act to authorize the people of Missouri Territory to form a constitution and state government” in 1820.

[23] George Adams Boyd, Elias Boudinot (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1952), p. 290, in a letter to Elias Boudinot on November 27, 1819.

[24] Charles Francis Adams, The Works of John Adams, Second President of the United States (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1856), p. 386, in a letter to Thomas Jefferson on December 18, 1819.

[25] Thomas Jefferson, The Works of Thomas Jefferson (New York and London: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1905), p. 157, in a letter to Hugh Nelson on February 7, 1820.

[26] Statutes at Large and Treaties of the United States of America, from December 1, 1845, to March 3, 1851, George Minot, editor (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1862), 31st Congress, 1st Session, Chapter 55, September 18, 1850, Vol. 9, pp. 462-465.

[27] Statutes at Large and Treaties of the United States of America, from December 1, 1851, to March 3, 1855, George Minot, editor (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1855), 33rd Congress, 1st Session, Chapter 59, May 30, 1854, Vol. 10, pp. 277-290.

[28] Hancock, Essays on the Elective Franchise, p. 22.

[29] Hancock, Essays on the Elective Franchise, pp. 22-23.

[30] Thomas Hudson McKee, The National Conventions and Platforms of All Political Parties, 1789-1905 (New York: Burt Franklin, 1971), pp. 18-20; Office of the Clerk, U.S. House of Representatives online, “Party Divisions” (at ht tp://clerk.house.gov/histHigh/Congressional_History/partyDiv.php); CNN AllPolitics.com, “Democratic Party History,” August 2, 2000 (at https://www.cnn.com/ELECTION/2000/conventions/democratic/features/history/).

[31] Eugene V. Smalley, A Brief History of the Republican Party. From Its Organization to the Presidential Campaign of 1884 (New York: John Alden, Publisher, 1885), p. 30.

[32] Hancock, Essays on the Elective Franchise, pp. 32-33.

[33] McKee, National Conventions and Platforms, pp. 97-99.

[34] McKee, National Conventions and Platforms, p. 91.

[35] McKee, National Conventions and Platforms, pp. 108-109.

[36] Harper’s Weekly online, “The Dred Scott Decision” (at https://blackhistory.harpweek.com/7Illustrations/Slavery/DredScottAd.htm) , in an advertisement that appeared in Harper’s Weekly, July 23, 1859.

[37] Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamation of the United States of America, from December 5, 1859, to March 3, 1863, George P. Spanger, editor (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1863), 37th Congress, 2nd Session, Chapter 54, April 16, 1862, Vol. 15, pp. 376-378.

[38] James D. Richardson, A Compilation of the Messages and Papers of the Presidents, 1789-1897 (Published by Authority of Congress, 1899), Vol. VI, 157-159, Proclamation by Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863.

[39] Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamation of the United States of America, from December, 1863, to December, 1865, George P. Spanger, editor (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1866), 38th Congress, 1st Session, Chapter 166, June 28, 1864, Vol. 13, p. 200; 1st Session, Chapter 144, June 20, 1864, Vol. 13, p. 144-145 [equalized pay]; and 2nd Session, Chapter 90, March 3, 1865, Vol. 13, pp. 507-509.

[40] Dominicus-von-Linprun-Gymnasium online, “American History: The Past of a Nation”

(at https://www.gymnasium-viechtach.de/ushistory/2_e.htm).

[41] Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamation of the United States of America, from December, 1865, to March, 1867, George P. Spanger, editor (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1868), 39th Congress, 2nd Session, Chapter 152, March 2, 1867, Vol. 14, pp. 428-430; Statutes, from December, 1867, to March, 1869 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1869), 40th Congress, 2nd Session, Chapter 69, June 22, 1868, Vol. 15, pp. 72-74.

[42] Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamation of the United States of America, from December, 1865, to March, 1867, George P. Spanger, editor (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1868), 39th Congress, 2nd Session, Chapter 152, March 2, 1867, Vol. 14, p. 429.

[43] Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamation of the United States of America, from December, 1867, to March, 1869, George P. Spanger, editor (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1869), 40th Congress, 1st Session, Chapter 6, March 23, 1867, Vol. 15, pp. 2-4.

[44] The Handbook of Texas online, “African Americans and Politics” (at https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbok/online/articles/print/AA/wmafr.html)

[45] Langston Hughes, Milton Meltzer, and Eric C. Lincoln, A Pictorial History of Blackamericans (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1983), p. 204.

[46] Hughes, Meltzer, and Lincoln, Pictorial History (1983), p. 205.

[47] Alabama Moments in American History online, “Alabama’s Black Leaders During Reconstruction” (at https://www.alabam amoments.state.al.us/sec26det.html); etc.

[48] The Handbook of Texas online, “Reconstruction” (at https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/print/AA/wmafr.html).

[49] Woodson, Negro Orators and Their Orations, p. 291, Sen. Hiram R. Revels from his speech on the Georgia Bill on March 16, 1870; p. 337, Rep. Richard H. Cain from his speech on the Civil Rights Bill on January 10, 1874; p. 379, Rep. Joseph H. Rainey from his speech made on March 5, 1872 in reply to an attack upon the colored state legislators of South Carolina by Representative Cox of New York; etc.

[50] Smalley, Brief History of the Republican Party, pp. 49-50; see also The Handbook of Texas online, “Ku Klux Klan” (at https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbok/online/articles/view/KK/vek2.html).

[51] Hughes, Meltzer, and Lincoln, Pictorial History (1983), p. 199; see also The Impeachment of Andrew Johnson online, “The New Orleans Massacre” (at https://www.impeach-andrewjohnson.com/06FirstImpeachmentDiscussion s/iiib-8a.htm); and Harper’s Weekly online, “The Riot in New Orleans” (at https://www.blackhistory.harpweek.com/7Illustrations/Reco nstruction/RiotInNewOrleans.htm).

[52] Woodson, Negro Orators and Their Orations, p. 291, Sen. Hiram R. Revels from his speech on the Georgia Bill on March 16, 1870; see also National Anti-Slavery Standard, September 26, 1868, “The South. The Rebel Perfidy in the Legislature. Colored Republicans Expelled” p. 1, and Georgia Secretary of State online, “Expelled Because of their Color: African-American Legislators in Georgia” (at https://www.sos.state .ga.us/Archives/ve/1/ec1.htm).

[53] Journal of the House of Representatives of the United States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1869), 40th Congress, 3rd Session, February 25, 1869, pp. 449-450; Journal of the Senate of the United States (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1869), 40th Congress, 3rd Session, February 25, 1869, p. 361.

[54] Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamation of the United States of America, from December, 1865, to March, 1867, George P. Spanger, editor (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1868), 39th Congress, 1st Session, Chapter 31, April 9, 1866, Vol. 14, pp. 27-30; 39th Congress, 2nd Session, Chapter 153, March 2, 1867, Vol. 14, pp. 428-430; Statutes at Large, from December, 1869, to March, 1871 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1871), 41st Congress, 2nd Session, Chapter 114, May 31, 1870, Vol. 16, pp. 140-146; Statutes at Large, from December, 1873, to March, 1875 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1875), 43rd Congress, 2nd Session, Chapter 114, March 1, 1875, Vol. 18, Part 3, pp. 335-337.

[55] Woodson, Negro Orators and Their Orations, p. 375, Rep. John R. Lynch from his speech on the Civil Rights Bill on February 3, 1875.

[56] The Handbook of Texas online, “Constitution Proposed in 1874” (at https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/view/CC/mhc12.html), and “Constitution of 1876” (at https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/view/CC/mhc7.html) .

[57] The Federal and State Constitutions Colonial Charters, and Other Organic Laws of the States, Territories, and Colonies, Francis Newton Thorpe, editor (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1909), pp. 2834-2835, 1876 North Carolina Constitution, Article 5, Section 1; Article 6, Section 4.

[58] Palm Beach Post online, Mark Caputo, “Black Judge’s Honor Restored in History Books,” February 27, 2002 (at https://www.myflorida.com/myflorida/governorsoffice/black_history/ju dge2.html); University of Dayton School of Law online, J. Whyatt Mondesire, “Felon Disenfranchisement: the Modern Day Poll Tax” (at https://academic .udayton.edu/race/04needs/voting06.htm).

[59] Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History online, “America in Ferment: The Tumultuous 1960s,” November 14, 2002 (at http:/ /www.gliah.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?HHID=369).

[60] PBS online, “The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow” (at https://www.pbs. org/wnet/jimcrow/stories_org_kkk.html); see also Cyberschool online, “African Americans Under Congressional Reconstruction” (at https://br t.uoregon.edu/cyberschool/history/ch15/rights.html); see also Hughes, Meltzer, and Lincoln, Pictorial History (1983), p. 199; etc.

[61] Ohio State University online, “Voting Restrictions: Jim Crow” (at https://1912.hist ory.ohio-state.edu/race/jimcrow.htm); see also SkyMinds.Net, “American Civilization: The Reconstruction” (at https://www.skyminds.net/ civilization/12.php).

[63] African-American History online, “The Black Codes of 1865” (at https:// aafroamhistory.about.com/library/weekly/aa121900a.htm); see also The Handbook of Texas online, “Black Codes,” p. 1 (at https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/view/BB/jsb1.html) .

[64] The Handbook of Texas online, “Reconstruction” (at https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/print/AA/wmafr.html).

[65] Woodson, Negro Orators and Their Orations, p. 305, Rep. Joseph H. Rainey, speaking on April 1, 1871, to explain how the Ku Klux Klan’s actions limit African-American people’s participation in the political process.

[66] CNN.com, “Timeline of the Civil Rights Movement, 1850-1970,” February 1, 2001 (at https://www.cnn.com/fyi/interactive/specials/bhm/story/timeline.html).

[67] African-American History online, “Creation of the Jim Crow South” (at https://a afroamhistory.about.com/library/weekly/aa010201a.htm); see also National Park Service online, “Jim Crow Laws” (at https://www.nps.go v/malu/documents/jim_crow_laws.htm); etc.

[68] Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883).

[69] United States Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Voting Section online, “Introduction to Federal Voting Rights Laws” (at https://www.usdoj.gov/crt/vo ting/intro.htm).

[70] The Handbook of Texas online, “African Americans and Politics,” p. 3 (at https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/print/AA/wmafr.html) , and “Texas Legislature,” pp. 4, 6 (at https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/print/TT/mkt2.html ).

[71] The Handbook of Texas online, “Texas Legislature,” p. 4 (at https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/print/TT/mkt2.html ).

[72] Nixon v. Herndon, 273 U.S. 536 (1927).

[73] Our Georgian History online, Col. Samuel Taylor, “Georgia’s Gilded Age: Georgia History 101” (at https:// www.ourgeorgiahistory.com/history101/gahistory09.html).

[76] Ohio State University online, “Voting Restrictions: Jim Crow” (at https://1912.hist ory.ohio-state.edu/race/jimcrow.htm).

[77] Jim Crow Guide to the USA online, Stetson Kennedy, Chapter 10 (at https:// www.stetsonkennedy.com/jim_crow_guide/chapter10_2.htm).

[78] Harvard University Press online, “The Transformation of Southern Politics,” from a book review of The Rise of Southern Politics, Earl Black and Merle Black, p. 2 (at https:// www.hup.harvard.edu/Newsroom/pr_rise_south_repubs.html); see also The Atlantic online, Grover Norquist, “Is the Party Over?,” p. 3 (at https://www .theatlantic.com/unbound/forum/gop/norquist1.htm)

[79] Grovey v. Townsend, 295 U.S. 45, 55 (1935).

[80] Smith v. Allwright, 321 U.S. 649, 658 (1944); see also The Handbook of Texas online, “White Primary” (at https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/print/WW/wdw1.html ).

[81] Neglected Voices online, “Speeches of African-American Representatives Addressing the Ku Klux Klan Bill of 1871,” pp. 5,10, Representative Robert B. Elliot, responding on April 1, 1871 to arguments that the Bill is unconstitutional, and that Ku Klux Klan is not violent (at https://www .law.nyu.edu/davisp/neglectedvoices/ElliotR.html).

[82 Woodson, Negro Orators and Their Orations, p. 354, Rep. James T. Rapier from his speech on the Civil Rights Bill on June 9, 1874.

[83] University of Missouri-Kansas City online, statistics provided by the Archives at Tuskegee Institute, “Lynching Statistics by Year” (at https://www.law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/shipp/lynchingyear.html ).

[84] Woodson, Negro Orators and Their Orations, p. 276, Rep. John R. Lynch from his speech in the case of his contested election.

[85] Robert L. Zangrando, The NAACP Crusade Against Lynching, 1909-1950 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1980), p. 16.

[86] Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates in the Second Session of the 73rd Congress of the United States of America (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1934), Vol. 78, Part 11, p. 11869, June 15, 1934.

[87] Hughes, Meltzer, and Lincoln, Pictorial History (1983), p. 269.

[89] Alabama Public Television online, Wayne Flint, “History of the 1901 Alabama Constitution” (at https://www.aptv.org/con stitution/history.html).

[90] The Handbook of Texas online, “African Americans and Politics” p. 6 at (https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/view/AA/wmafr.html ). &nbs p;

[91] Bullock v. Carter, 405 U.S. 134 (1972).

[92] Bullock v. Carter, 405 U.S. 134, 144 (1972).

[93] Statutes at Large, Treaties, and Proclamation of the United States of America, from December, 1865, to March, 1867, George P. Spanger, editor (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1868), 39th Congress, 2nd Session, Chapter 152, March 2, 1867, Vol. 14, pp. 428-429.

[94] The Federal and State Constitutions (1909), Vol. V, pp. 2800-2803, 2814, 1868 North Carolina Constitution, “Declaration of Rights,” #1, #10, #33, Article 6, Section 1.

[95] The Federal and State Constitutions (1909), Vol. V, pp. 2822-2823,2834-2835, 1876 North Carolina Constitution, “Declaration of Rights,” #1, #10, Article 5, Section 1; Article 6, Section 4.

[96] The Federal and State Constitutions (1909), pp. 2067-2068, 1832 Mississippi Constitution, Amendment 13, Article VIII; see also p. 2079, 1868 Mississippi Constitution, Article 7, Section 2; pp. 2120-2121, 1890 Mississippi Constitution, Article 12, Sections 241, 243-244.

[97] The Federal and State Constitutions (1909), pp. 3276, 3279-3280, 1865 South Carolina Constitution, Article 4, Ordinance, Section 3; see also pp. 3281, 3297-3298, 1868 South Carolina Constitution, Article 1, Sections 1-2, Article 8, Sections 2, 12; see also pp. 3307-3308, 1895 South Carolina Constitution, “Declaration of Rights,” #9, “Right of Suffrage,” Sec. 3 (c).

[98] The Federal and State Constitutions (1909), pp. 1449, 1462-1463, 1868 Louisiana Constitution, “Bill of Rights,” #1-3, 98, 103; see also pp. 1471, 1502, 1879 Louisiana Constitution, “Bill of Rights,” #5, #188; see also pp. 1562-1563, 1898 Louisiana Constitution, “Bill of Rights,” #197, Sections 2-4, #198.

[99] The Federal and State Constitutions (1909), pp. 704, 719-720, 1868 Florida Constitution, Article 1, 15.

[100] The Federal and State Constitutions (1909), pp. 132, 144, 1867 Alabama Constitution, “Declaration of Rights,” #1, Article 7, Section 2; see also p. 154, 1875 Alabama Constitution, “Declaration of Rights,” #1, Article 8, Section 1; see also pp. 209-210, 215, 1901 Alabama Constitution, “Declaration of Rights,” #181, #194.

[101] The Federal and State Constitutions (1909), pp. 3873-3875, 1870 Virginia Constitution, “Bill of Rights,” #1 Article 3, Section 1; see also pp. 3904-3907, 1902 Virginia Constitution, “Bill of Rights,” #1, #18-19.

[102] The Federal and State Constitutions (1909), p. 210, 1901 Alabama Constitution, Article 8, #181.

[103] Columbia Journalism Review online, “CJR Dollar Conversion Calculator” (at https://www.cjr.org/resources/inflater.asp).

[104] Florida: History, People & Politics online, Unit 3: Florida as a State; “Civil Rights: The Case of Florida; Black Codes” (at https://www.fcim.org/ flhistory/unit3_t4_case.htm).

[106] Richard Allen, The Life Experience and Gospel Labors of the Rt. Rev. Richard Allen (New York, Nashville: Abingdon Press, reprint of an earlier edition, 1960), p. 26.

[107] Allen, Life Experience (1960), p. 21.

[108] Virtual Black History Museum in Louisiana online, “1800s Interactive First’s Timeline,” p. 3 (at https://www.sabine. k12.la.us/mjhs/Archives/1800.htm).

[110] Hughes, Meltzer, and Lincoln, Pictorial History (1983), p. 202; see also “Reconstruction” (at https://www.stanfo rd.edu/paherman/reconstruction.htm).

[111] The Handbook of Texas online, “African Americans and Politics” (at https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/print/AA/wmafr.html), and “Reconstruction” (at https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/view/RR/mzr1.html).

[112] Neglected Voices online, Representative Richard H. Cain, responding on February 3, 1875, to arguments that the Bill would unconstitutionally infringe the rights of whites (at ht tp://www.law.nyu.edu/davidp/neglectedvoices/RaineyFeb031875.html).

[116] Biographical Directory of the American Congress 1774-1927 (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1928), pp. 435-444, 479-488.

[117] Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History online, “Voting Rights, Period: 1960s,” p. 1 (at http:/ /www.gliah.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?HHID=369).

[118] Alabama Public Television online, Wayne Flint, “History of the 1901 Alabama Constitution,” p. 5 (at https://www.aptv.org/con stitution/history.html).

[119] Alabama Public Television online, Wayne Flint, “History of the 1901 Alabama Constitution,” p. 6 (at https://www.aptv.org/con stitution/history.html); see also World Socialist Web Site, Jerry White, “Florida’s Legacy of Voter Disenfranchisement,” April 6, 2001, p. 2 (at https://www. wsws.org/articles/2001/apr2001/flor-a09.shtml).

[120] Mike Kingston, Sam Attlesey, and Mary G. Crawford, Political History of Texas (Austin: Eakin Press, 1992), p. 187.

[122] Democratic National Committee online, “Brief History of the Democratic Party” (at https://www.democrats.org/ about/history.html), the article states, “With the election of Harry Truman, Democrats began the fight to bring down the final barriers of race and gender.” (emphasis added).

[123] Documentary History of the Truman Presidency online, “The Truman Administration’s Civil Rights Program: The Report of the Committee on Civil Rights” and President Truman’s Message to Congress of February 2, 1948, Vol. 11, p. 3 (at https://www.lexisnexis.com/academic/2upa/Aph/truman_docs/g uide_intros/tru11.htm), and “The Truman Administration’s Civil Rights Program: President Truman’s Attempts to Put the Principles of Racial Justice into Law, 1948-1950,” Vol. 12, pp.

1-2 (at https://www.lexisnexis.com/academic/2upa/ Aph/truman_docs/guide_intros/tru11.htm).

[124] The Handbook of Texas online, “Democratic Party,” p. 2 (at https://www.tsha.utexas.edu/handbook/online/articles/print/DD/wad1.html ).

[125] Colorado College online, “A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States of America,” p. 8 (at https://www2.coloradocollege.edu/Dept/PS/faculty/loevy/civil%20rights.h tml).

[126] Truman Presidency online, “Report of the Committee on Civil Rights,” Vol. 11, p. 3 (at https://www.lexisnexis.com/academic/2upa/Aph/truman_docs/g uide_intros/tru11.htm).

[127] United States of America Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates in the Second Session of the Eightieth Congress Second Session (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1948), Vol. 94, Part 1, p. 927 February 2, 1948; see also Truman Presidency online, “Report of the Committee on Civil Rights,” Vol. 12, p. 13, (at https://www.lexisnexis.com/academic/2upa/Aph/truman_docs/guide_intros/t ru12.htm).

[128] Truman Presidency online, “Attempts to Put the Principles of Racial Justice into Law,” Vol. 12, p. 2 (at https://www.lexisnexis.com/academic/2upa/Aph/truman_docs/gu ide_intros/tru12.htm).

[129] Truman Presidency online, “Attempts to Put the Principles of Racial Justice into Law,” Vol. 12, p. 2 (at https://www.lexisnexis.com/academic/2upa/Aph/truman_docs/gu ide_intros/tru12.htm).

[130] Time online, Karen Tumulty, “Trent Lott’s Segregationist College Days,” p. 2 (at http:/ /www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,399310,00.html), Lott stated that “…if the rest of the country had followed our [Mississippi’s segregationist Dixiecrat party] lead, we wouldn’t have had all these problems over the years either.”

[132] Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

[133] The Civil Rights Act of 1964: The Passage of the Low that Ended Racial Segregation, Robert D. Loevy, editor (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1997), pp. 26, 27, 33; see also Civil Rights-” 1957: Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Constitutional Rights of the Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate Eighty-Fifth Congress First Session (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1960), pp. 125-131; Civil Rights Act of 1960: Hearings Before the Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate Eighty Sixth Congress Second Session on H.R. 8601 (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1960), pp. 2-7.

[134] The Civil Rights Act of 1964, pp. 26, 27, 28, 30, 31.

[135] The White House Historical Association online, “African Americans and the White House: the 1950s” (at https://www.whitehousehistory.org/04_history/subs_t imeline/c_africans/frame_c_1950.html).

[136] Civil Rights-” 1957: Hearings, Part 3, p. 131; “Civil Rights Act of 1957” online, Part 3 (at http: //www.nv.cc.va.us/home/nvsageh/Hist122/Part4/CRact57.htm); see also The Civil Rights Act of 1964, pp. 27, 30-31; civilrights.org, “Civil Rights Act of 1964,” (at https://www.civilrights.org/library/permanent_collection/resources/1964cra.html ); “Voting Rights Act of 1965,” 42 U.S.C. 1973I.

[137] United States of America Congressional Record: Proceedings and Debates of the 88th Congress (Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office, 1963), 1st Session, Vol. 109, Part 9, June 27, 1963, pp. 11864-11865; Library of Congress online, “Today in History,” January 23, 2002, pp. 1-2 (at https://memory.loc.gov/am mem/today/jan23.html).

[139] Congressional Quarterly (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Service, 1962), 87th Congress, 2nd Session, 1962, Vol. 18, pp. 630, 654.

[140] Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966).

[141] Congressional Quarterly (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Service, 1965), 88th Congress, 2nd Session, 1964, Vol. 20, pp. 606, 696.

[142] Congressional Quarterly (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Service, 1966), 89th Congress, 1st Session, 1965, Vol. 21, pp. 984, 1063.

[143] Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History online, “Voting Rights, Period: 1960s,” p. 2 (at http:/ /www.gliah.uh.edu/database/article_display.cfm?HHID=369).

[147] Woodson, Negro Orators and Their Orations, pp. 379-380, Rep. Joseph H. Rainey from his speech made on March 5, 1872 in reply to an attack upon the colored state legislators of South Carolina by Representative Cox of New York.

[148] James Haskins, Distinguished African American Political and Governmental Leaders (Phoenix: Oryx Press, 1999), p. 155; see also USA Today online, “Conventions 2000: Rep. J.C. Watts,” p. 1 (at https://www.usato day.com/community/chat/0817watts.htm); African American Political History online (at htt p://www.garyjosejames.com/AfricanAmericanPoliticalHistory.html).

[149] Maryland State Archives online, Michael Steele,”Lieutenant Governor,” January 27, 2003 (at https://www.mdarchives.state.md.us/msa/mdmanual/08conoff/html/msa13921 .html); see also Ohio Republican Party online, “Leadership: Lt. Governor Jennette Bradley” (at https://www.ohiogop.org/Victory2002.asp?FormMod e=Candidates&CID=8&T=Lt%2E+Governor+Jennette+Bradley); see also Black News Weekly online,”Ga. Could Send 5 Blacks to Congress,” p. 2 (at https://www.blacknewsweekly.c om/210.html); see also The Weekly Standard online, Beth Henary, “Things Go Right in Texas,” November 7, 2002 (at https://www.weeklystandard.com/Content/Public/Articles/000/000/001/ 875ahmds.asp); etc.

Today, most Americans are taught Black History from a southern point of view. That is, they are exposed to the slave trade and the atrocities of slavery that were common in the South but hear nearly nothing about the many positive things that occurred in the North.

Today, most Americans are taught Black History from a southern point of view. That is, they are exposed to the slave trade and the atrocities of slavery that were common in the South but hear nearly nothing about the many positive things that occurred in the North. Similarly, most Americans are unaware that American colonies passed anti-slavery laws before the American Revolution, but that those laws were vetoed by Great Britain, who insisted on the continuance of slavery in America. In fact, several Founders who owned slaves while British citizens freed them once America declared her independence. Sadly, we have been taught to identify Founding Fathers who owned slaves but are unaware of the greater number who opposed slavery or worked with anti-slavery societies.

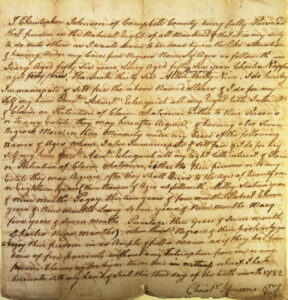

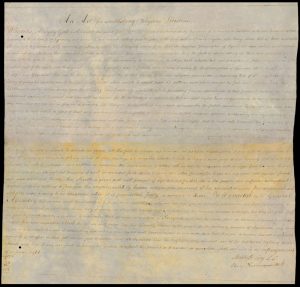

Similarly, most Americans are unaware that American colonies passed anti-slavery laws before the American Revolution, but that those laws were vetoed by Great Britain, who insisted on the continuance of slavery in America. In fact, several Founders who owned slaves while British citizens freed them once America declared her independence. Sadly, we have been taught to identify Founding Fathers who owned slaves but are unaware of the greater number who opposed slavery or worked with anti-slavery societies. In this 1782 document, Christopher Johnson, a soldier in the American Revolution, declares that he is “fully persuaded that freedom is the natural rights of all mankind & that it is my duty to do unto others as I would desire to be done by in the like situation.” Having fought a war to win his own political freedom, and invoking the Golden Rule delivered by Jesus in Matthew 7:12, he freed (that is, manumitted) his slaves.

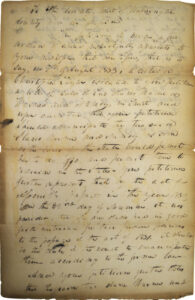

In this 1782 document, Christopher Johnson, a soldier in the American Revolution, declares that he is “fully persuaded that freedom is the natural rights of all mankind & that it is my duty to do unto others as I would desire to be done by in the like situation.” Having fought a war to win his own political freedom, and invoking the Golden Rule delivered by Jesus in Matthew 7:12, he freed (that is, manumitted) his slaves. In this 1837 document, Dorcas, a Black American who is “a free woman of color,” petitions the court to recognize the legality of two slaves that were freed. According to the Tennessee Act of 1831,4 freed slaves were required to move out of the state, but the subsequent act of 18335 permitted slaves to remain in the state if they had received their freedom prior to 1831. In her letter, Dorcas affirms that “the said two slaves, Warner and Nancy” had received “their freedom long before the passage of the act of 1831” and asks the court to take appropriate action for ensuring their freedom.

In this 1837 document, Dorcas, a Black American who is “a free woman of color,” petitions the court to recognize the legality of two slaves that were freed. According to the Tennessee Act of 1831,4 freed slaves were required to move out of the state, but the subsequent act of 18335 permitted slaves to remain in the state if they had received their freedom prior to 1831. In her letter, Dorcas affirms that “the said two slaves, Warner and Nancy” had received “their freedom long before the passage of the act of 1831” and asks the court to take appropriate action for ensuring their freedom.

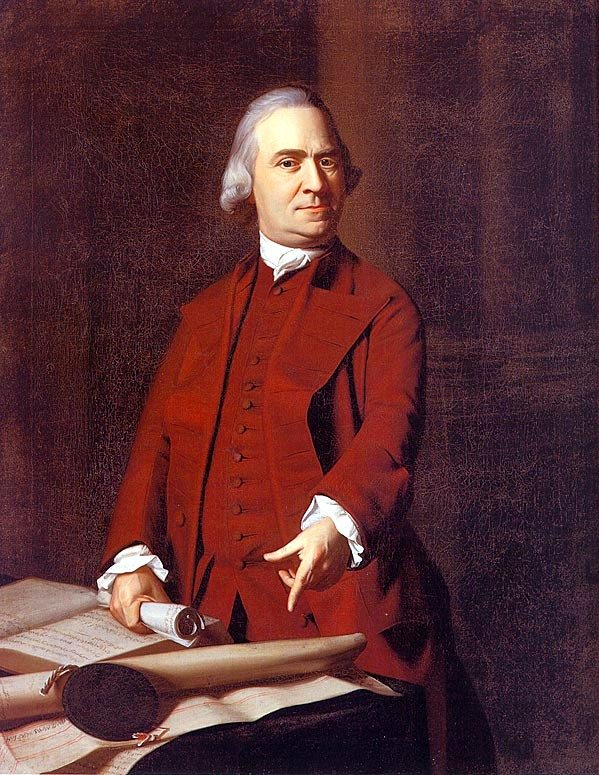

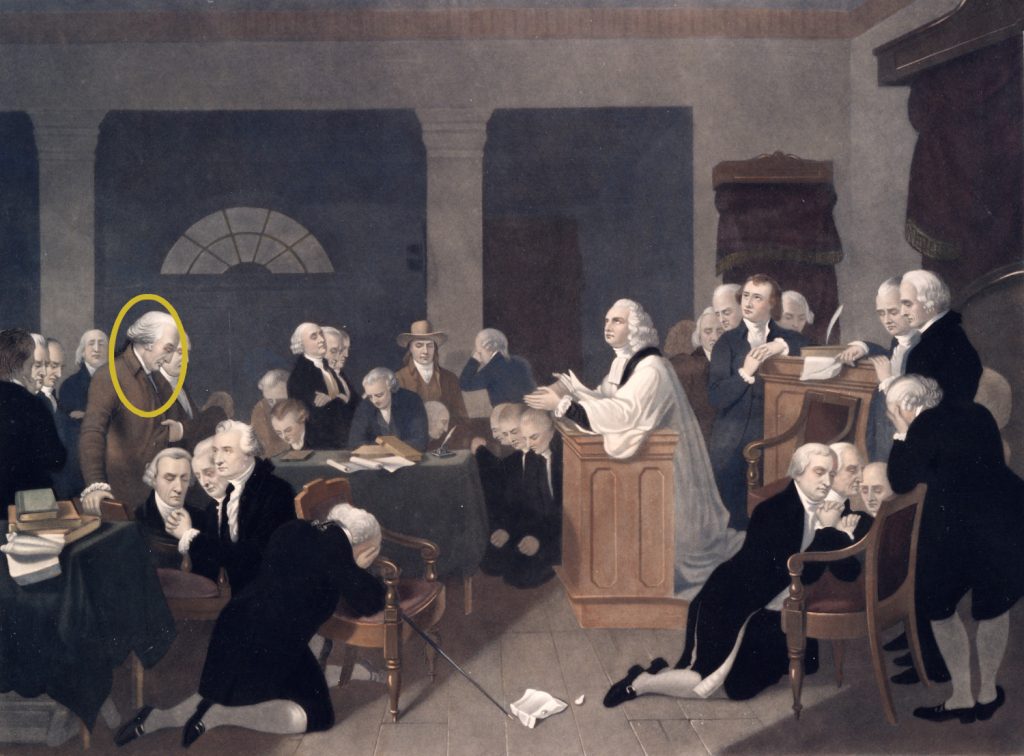

In this situation of this assembly, groping, as it were, in the dark to find political truth, and scarce able to distinguish it when presented to us, how has it happened, sir, that we have not hitherto once thought of humbly applying to the Father of Lights to illuminate our understandings? In the beginning of the contest with Britain when we were sensible of danger, we had daily prayers in this room for the Divine Protection. Our prayers, sir, were heard, and they were graciously answered. . . And have we now forgotten that powerful Friend? or do we imagine we no longer need His assistance? I have lived, sir, a long time; and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth: that God governs in the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without His notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without His aid? We have been assured, sir, in the Sacred Writings that except the Lord build the House, they labor in vain that build it. I firmly believe this; and I also believe that without His concurring aid, we shall succeed in this political building no better than the builders of Babel . . . and we ourselves shall become a reproach and a byword down to future ages. I therefore beg leave to move, that henceforth prayers imploring the assistance of Heaven, and its blessings on our deliberations, be held in this Assembly every morning before we proceed to business.

In this situation of this assembly, groping, as it were, in the dark to find political truth, and scarce able to distinguish it when presented to us, how has it happened, sir, that we have not hitherto once thought of humbly applying to the Father of Lights to illuminate our understandings? In the beginning of the contest with Britain when we were sensible of danger, we had daily prayers in this room for the Divine Protection. Our prayers, sir, were heard, and they were graciously answered. . . And have we now forgotten that powerful Friend? or do we imagine we no longer need His assistance? I have lived, sir, a long time; and the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth: that God governs in the affairs of men. And if a sparrow cannot fall to the ground without His notice, is it probable that an empire can rise without His aid? We have been assured, sir, in the Sacred Writings that except the Lord build the House, they labor in vain that build it. I firmly believe this; and I also believe that without His concurring aid, we shall succeed in this political building no better than the builders of Babel . . . and we ourselves shall become a reproach and a byword down to future ages. I therefore beg leave to move, that henceforth prayers imploring the assistance of Heaven, and its blessings on our deliberations, be held in this Assembly every morning before we proceed to business.

The Bible has often been described as the book that built America. As President Franklin Roosevelt affirmed:

The Bible has often been described as the book that built America. As President Franklin Roosevelt affirmed: For example, Benjamin Rush (a signer of the Declaration of Independence) in 1809 helped establish the first Bible Society in America.

For example, Benjamin Rush (a signer of the Declaration of Independence) in 1809 helped establish the first Bible Society in America.

On March 18, 1877, Frederick Douglass became the first African American confirmed by the U. S. Senate to serve in a presidential appointment.

On March 18, 1877, Frederick Douglass became the first African American confirmed by the U. S. Senate to serve in a presidential appointment.

Black History Month is a special time to focus on black history, which interestingly often involves not just Black Americans but also those of other races. As famous Black American minister Richard Allen reminded his brethren during the Founding Era, “Many of the white people have been instruments in the hands of God for our good [and] are now pleading our cause with earnestness and zeal.”

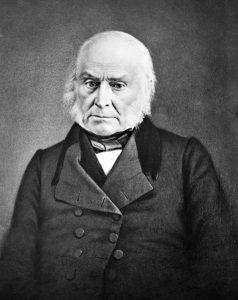

Black History Month is a special time to focus on black history, which interestingly often involves not just Black Americans but also those of other races. As famous Black American minister Richard Allen reminded his brethren during the Founding Era, “Many of the white people have been instruments in the hands of God for our good [and] are now pleading our cause with earnestness and zeal.”  Adams also led the legal defense of the African slaves in the famous Amistad case

Adams also led the legal defense of the African slaves in the famous Amistad case

January 16, 1786, was the day that the Virginia Assembly adopted the

January 16, 1786, was the day that the Virginia Assembly adopted the  1779

1779

A Founding Father who exerted great influence in our constitutional government was Alexander Hamilton. As a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, and one of its thirty-nine signers, he played what would be considered a minor role in the debates of the Convention itself. However he (along with John Jay and James Madison) became one of the three men most responsible for the adoption and ratification of the Constitution through the writing and publication of a series of articles which became known as The Federalist Papers.

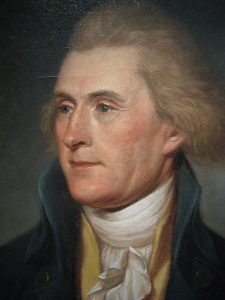

A Founding Father who exerted great influence in our constitutional government was Alexander Hamilton. As a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, and one of its thirty-nine signers, he played what would be considered a minor role in the debates of the Convention itself. However he (along with John Jay and James Madison) became one of the three men most responsible for the adoption and ratification of the Constitution through the writing and publication of a series of articles which became known as The Federalist Papers. (By the way, during that election cycle in 1800, a number of ministers preached and published pulpit sermons against Jefferson, including Hamilton’s good friend, the Rev. John Mitchell Mason.)

(By the way, during that election cycle in 1800, a number of ministers preached and published pulpit sermons against Jefferson, including Hamilton’s good friend, the Rev. John Mitchell Mason.)