John Lathrop (1740-1816) Biography:

John Lathrop, also spelled Lothrop, was born in Norwich, Connecticut. He graduated from Princeton in 1763 and began working as an assistant teacher with the Rev. Dr. Eleazar Wheelock of Lebanon, Connecticut, at Moor’s Indian Charity School. He studied theology under Dr. Wheelock (who later founded Dartmouth College) and became licensed to preach in 1767, ministering among the Indians. In 1768, he became the preacher of the Second Church of Boston, but as Boston was central in the rising tensions and violence with the British leading up to the American War for Independence, he relocated to Providence, Rhode Island. When the Founding Fathers declared independence from Britain in 1776, Lathrop returned to Boston. When Dr. Pemberton of New Brick Church was taken ill, Lathrop was asked to become the assistant to the pastor. When Pemberton passed away a year later, Lathrop became pastor of New Brick Church but also retained the pastorate of Second Church, merging it into New Brick in 1779. Lathrop remained pastor until his death from lung fever in 1816. He had served as President of the Massachusetts Bible Society and the Society of Propagating the Gospel in North America, and he was also a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Antiquarian Society. Numerous of his sermons were published, including the following one delivered on December 15, 1774.

also spelled Lothrop, was born in Norwich, Connecticut. He graduated from Princeton in 1763 and began working as an assistant teacher with the Rev. Dr. Eleazar Wheelock of Lebanon, Connecticut, at Moor’s Indian Charity School. He studied theology under Dr. Wheelock (who later founded Dartmouth College) and became licensed to preach in 1767, ministering among the Indians. In 1768, he became the preacher of the Second Church of Boston, but as Boston was central in the rising tensions and violence with the British leading up to the American War for Independence, he relocated to Providence, Rhode Island. When the Founding Fathers declared independence from Britain in 1776, Lathrop returned to Boston. When Dr. Pemberton of New Brick Church was taken ill, Lathrop was asked to become the assistant to the pastor. When Pemberton passed away a year later, Lathrop became pastor of New Brick Church but also retained the pastorate of Second Church, merging it into New Brick in 1779. Lathrop remained pastor until his death from lung fever in 1816. He had served as President of the Massachusetts Bible Society and the Society of Propagating the Gospel in North America, and he was also a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Antiquarian Society. Numerous of his sermons were published, including the following one delivered on December 15, 1774.

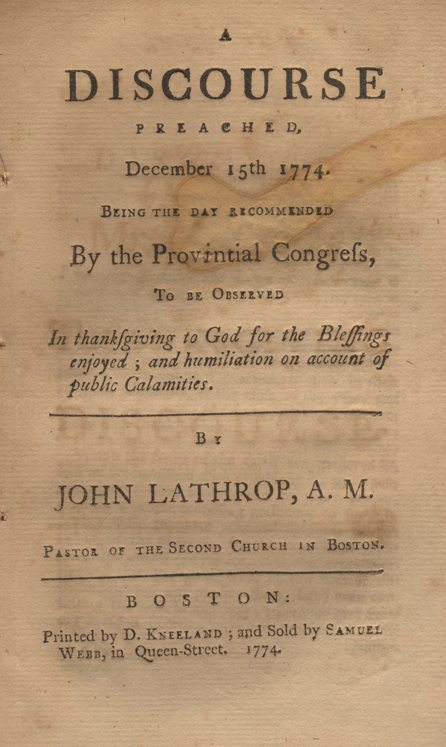

A

DISCOURSE

PREACHED,

December 15th 1774.

Being the Day Recommended

By the Provincial Congress,

To Be Observed

In thanksgiving to God for the Blessings

enjoyed; and humiliation on account of

public Calamities.

By

JOHN LATHROP, A. M.

Pastor of the Second Church in Boston.

A

DISCOURSE,

FROM

PSALM CI. I.

I will sing of mercy and judgment: unto thee O Lord will I sing.

AUTHORIZED by a divine precept, 1 and excited by the feelings of gratitude, the inhabitants of these northern provinces, have made it their constant practice, to meet in their religious assemblies, at the close of the year, and devoutly offer unto the Lord, their sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving.

When the fruits of the earth are gathered in, and we are furnished with provisions for an expensive winter season, nothing can be more proper, than for a people professing godliness, to unite in paying their thankful acknowledgments to the father of the universe, for the expressions of his goodness.—And we rejoice, that the representatives of this Province, who, in the present distracted state of our public affairs, have been consulting the most proper ways to recover and secure our invaded liberties, were not unmindful of the blessings we receive from God almighty; but have invited us to observe this day of general thanksgiving.

But although we have much reason to bless the Lord, for the many expressions of his goodness, through the course of the last year, it is proper, even on this day of festivity, “to humble ourselves before God, on account of those sins, for which he hath suffered our present calamities to come upon us, and implore the divine blessing, that by the assistances of his grace, we may be enabled to reform whatever is amiss, that so God may be pleased to continue to us the blessings we enjoy, and remove the tokens of his displeasure.” 2

The exercises of this day, will therefore be different from what have been usual; and I could think of no passage of scripture, more suitable to place at the head of a discourse, in which we are to have respect, both to the blessings of divine providence, and the public calamities which have befallen us, than the words of David, which have now been read.

A celebrated commentator on the text, has the following observations;–“When God in his providence exerciseth us with a mixture of Mercy and Judgment, it is our duty to sing, and sing unto him both of the one and the other: We must be suitably affected with both, and make suitable acknowledgments of both.” Agreeable to the Chaldee paraphrase,–“If thou bestowest mercy upon me, or if thou bringest any judgment upon me, before thee, O Lord, will I sing my hymns for all.” 3

Let me then ask your attention, while I mention some of the blessings which God is pleased to bestow upon us; and take notice of the principal calamities, which, in righteous Judgment, he has suffered to befall us.

You will be sensible, the time allowed the preacher on a day of thanksgiving, will not admit of an exact enumeration, either of the Blessings bestowed upon us, or the calamities under which we suffer; we must therefore confine our attention to those which are confessedly of the most importance: But should I a little exceed the limits commonly observed on these Occasions, the nature of the subject, I hope, will be an apology for me.

All who possess their belief of the holy Scriptures, will be free to acknowledge, the mercy of God revealed in the gospel, demands our first, our principle attention.

Such is the darkness of the human mind, that had not the children of men, been favoured with the light of divine truth, they would never have found the say to glory. But the father of the universe, in compassion to the human race, exposed to misery, in consequence of the spread of moral evil through the World, was pleased to give his Son, that whosoever believeth on him should not perish, but might have eternal life.– 4 The day-spring from on high hath visited us, to give light to them that sit in darkness, and in the shadow of death, to guide our feet into the way of peace.-—We have reason to join with the angels, and multitude of the heavenly host, ascribing glory to God in the highest, that on earth there is peace, and good will towards men.5

The mercy of God revealed to a guilty World, in the gift of his Son Jesus Christ, will claim an everlasting tribute of Praise.—How deplorable would our condition have been, had the author of our existence, seen fit to leave us to the power of those lusts, which war against the Soul.– 6 Satan, the enemy of all good, was able to seduce our once innocent parents from their loyalty, and render them obnoxious to the wrath of their creator.—And had not Jesus Christ who is stronger than the strong man armed, and is able to subdue all things to himself, 7 undertaken the work of redemption, none of our guilty race, could have entertained a hope of future happiness, or even of life from the dead.

But by the gospel of the grace of God, life and immortality are brought to light.—By the gospel we are made certain of a future state; and the author of our Salvation, has not only suffered for our offences, and rose again for our justification, but clearly pointed out the path to heaven.

We have reason to be thankful, that notwithstanding, all our unworthiness, the gospel is continued among us, and we have liberty to worship our creator, according to the dictates of conscience, without disturbance or molestation.

Many have endured the greatest afflictions, and suffered the most cruel death, not only under pagan Monarchs, and the influence of Romish inquisitions, but under the arbitrary government of tyrants, who in ages past, disgraced the throne of Britain.

Not to mention persecutions in foreign countries, or look back to the ages of darkness and gross ignorance, in our own nation, and in the short time which past between the restoration of Charles the IId, and the glorious revolution, besides many that were inhumanely murdered, five thousand Protestants died in prisons, on account of their religion. 8

But while multitudes have suffered, because they did not choose to submit to unscriptural usages, or attend to modes and forms of human invention, we have enjoyed full liberty of conscience: In no part of the world has the right of private judgment, in matters of religion, been more sacredly maintained, than in America.

In some provinces, all sects and denominations, professing Christianity, Roman Catholics not excepted, are freely tolerated.

In those provinces where the church of England is established by law, dissenters are allowed their own forms of worship; but required indeed, as in most parts of the world, where a form of worship is established by authority, to pay their proportion towards the support of the established clergy.

And in these northern provinces, where the order and discipline, which have generally been observed in the congregation or Presbyterian churches, are favoured with an establishment, dissenters from our worship and discipline, are not only tolerated, but upon their professing to be of other denominations, they are excused from bearing any part of the ministry, and form of worship established by law. 9

Such tenderness to our brethren who differ from us in their sentiments with respect to the modes of worship, or the discipline of the church, is much to the honour of this and the other New-England Provinces.

As the blessings of the gospel, and the privileges of a religious nature which we enjoy, are exceeding precious, we ought to remember them with gratitude, and render to the Lord the warmest affections of our heart for the continuance of them.

We have reason to be thankful “for the smiles of divine Providence upon us with regard to the seasons of the year, and the general health which has been enjoyed.”—God has smiled on the labour of the husbandmen through the course of the year: He has been pleased to grant those showers of rain, and kind influences of the Heavens, which were necessary to perfect the fruits of the earth. Our markets are filled with a variety of provisions; and notwithstanding the multitude of strangers among us, we cannot complain that the necessaries of life are sold us at an extravagant price. 10

We have been visited with no uncommon sickness in this Town, or through the land. This pestilence has not walked in darkness, nor has the destruction wasted at noon day.—Such indeed is human frailty, that every year we must expect to bury some of our friends and valuable acquaintance: But we have reason to be thankful, when mortal diseases have not been general.

“And in particular”, we have reason to be thankful, “from a consideration of the union which so remarkably prevails, not only in this Province, but through the continent, at this alarming crisis.”

It must be acknowledged, America never saw a day so alarming as the present—The unhappy controversy which now subsists between Great-Britain and these Colonies is more painful than any of the distressing wars we have formerly been engaged in.—When the Savages annoyed our infant settlements, or those who we used to consider as natural Enemies threatened to invade us, duty and interest pointed us to the means of safety.—Our young men offered themselves freely to engage in the defence of their country; and being succeeded by Heaven, victory from time to time, crowned their endeavours.—

But when the parent State is contending with us, nothing but the last extremity,–nothing but the preservation of life, or that which is of more importance Liberty, can ever prevail with us to make resistance.

We glory in our attachment to the House of Hanover.—We consider Britain as our native land.—We shall therefore bear much, we shall suffer many hardships, before we can entertain a single wish to the disadvantage of our brethren on the other side the Atlantic.—We never will rebel against the Sovereign of the British dominions.—However provoked,–however oppressed,–however threatened with Slavery and wretchedness, we will never be excited to any other resistance, than what the impartial world shall Judge absolutely necessary to our own defence.

Britons and Americans, subjects of the same Crown, connected by the ties of nature, by interest and by religion, maintained the most perfect harmony, and felt the purest joy in each others happiness for more than a hundred years: And would to God, that harmony had never been disturbed!

But by reason of false, and injurious representations which were made by some, from whom indeed we might have expected better things, a system of government, not long since, was formed for the colonies in America, too degrading and oppressive for British Subjects, quietly to bear.

The Parliament of Great-Britain, some years ago, passed an Act, declaring “That his Majesty in Parliament, OF RIGHT, had power to bind the people of these Colonies by Statutes IN ALL CASES WHATSOEVER.”—“The import of the words above quoted, needs no discant: For the wit of man, cannot possibly form, a more clear, concise, and comprehensive definition and sentence of slavery, than these expressions contain.” 11

In this light was the declaratory Act viewed by Americans in general.—And by several Acts which have passed since, the inhabitants of these colonies have been confirmed in their apprehensions, that the Government at home, had determined to treat them, not as obedient children, but rather as Servants; and let them know that they held life, and property, and whatever is dear to them, at the pleasure of masters three thousand miles distant; on whose ambition they can have no check, on whose power they have no control.

Alarmed it may well be supposed the Americans were, and not doubting but their gracious King would hear their Petitions, and deliver them from their gracious King would hear their Petitions, and deliver them from their troubles, they addressed the throne in the most humble and dutiful manner; but their Petitions were rejected, and treated with contempt. Arbitrary measures were taken to prevent the complaints of the injured and distressed from reaching the Royal ear.—“Assemblies have been frequently dissolved, contrary to the rights of the people, when they attempted to deliberate on grievances.” 12

“The attacks on our rights were incessant”: Not satisfied with taking away our money, in such quantities, and for such purposes as they pleased, the Parliament proceeded, in direct methods, to invade our Charters, and threaten us with transportation to Great-Britain, in order to be tried, on supposition any resistance should be made, to what the Americans might consider as intolerable oppression.

“Hard is our fate, when, to escape the character of rebels, we must be degraded into that of slaves: As if there was no medium, between the two extremes of anarchy and despotism, where innocence and freedom could find repose and safety.” 13

Such were our sufferings, particularly in this Province,–such our fears, and such the apprehensions of all America, that it was judged expedient a Continental Congress should be convened as soon as possible to take our public grievances under consideration, and point out the most proper means of redress.

Deputies were accordingly chosen by the several colonies from New-Hampshire to South-Carolina.—They entered upon the important business to which they were appointed, as it become men professing the religion of Christ.—They made their humble addresses to the Lord of the universe for the influences of his Spirit, to lead them in a safe path, succeed their endeavours to extricate an injured people from their present difficulties, and lay a foundation for lasting tranquility, both in Great-Britain and America.—Many prayers were made for them in our respective churches, and by serious people in their private retirements.

The members who met in that illustrious Assembly, were men of the first character in the several provinces: Men who best understood the rights of America, and were best able to judge what measures would be most proper for the inhabitants in general to adopt, in order to recover and secure them.

After Solemn deliberation on the important subjects which lay before them, they came to a result, which has been made known to the World, and with which you are all acquainted.—We have much reason for thankfulness that the members of the Congress were so remarkably united.—Those among us who wished the late oppressive acts of parliament to be carried into execution, were free to declare, the Colonies would never unite, and endeavoured to make us believe, the Gentlemen who were chosen to represent the several Provinces, were of sentiments extremely different from each other. Had the Congress dissolved without forming any general plans, or had the members been greatly divided in their opinions, it would have discouraged the friends of Liberty, and perhaps given a fatal turn to our public affairs: But their Union has not only expressed the Union of their constituents, but had an happy influence to establish many in their friendship to the American cause, who were before, wavering—Their doings will, as they most certainly ought to, have the force of laws.—The man that ventures to rise in opposition to them, opposes both the wisdom and strength of this amazing continent; and certainly no man in his senses will act so foolish, so desperate a part.

The penalty to be inflicted on such, if any such there should be, as in contempt of the American Association, determine to pursue their own private emoluments, regardless of the public good, is not immediate death, but it must be confessed, it is very little short of it.—You will allow me to repeat some parts of the resolves which declare it.—Whenever it shall appear to the Committees which are, or may be chosen in every county, city, and town, for executing the plans of the continental Congress, that any person within their respective limits, has violated the Association, the truth of the case is to be published,–“To the end, that all such foes to the rights of British America, may be publickly known, and universally contemned as the enemies of American Liberty; and thenceforth we respectively will break off all dealing with him or her.—And we do further agree and resolve, that we will have no trade, commerce, dealings or intercourse whatsoever, with any Colony or Province in North-America, which shall not accede to, or which shall hereafter violate this Association, but will hold them as unworthy of the rights of freemen, and as inimical to the liberties of their Country.”

Who would not dread such a punishment, as much as any temporal evil that can be mentioned?—To cut off from the privileges of human society and lie exposed to universal contempt, is next, if not equal to being cut off from among the living.—People may affect to sport with popular resentment as much as they please, when they have a few companions to flatter and encourage them; but when that punishment, which they may ridicule at a distance, or think little of in its beginnings, falls upon them in earnest, they must have fortitude more than human, to support long under it.—A man of any tender feelings will be unhappy, when he knows a few of his acquaintance are offended with him; how wretched must he then be, who is assured the resentments of almost this whole continent, are raised against him, and that there is no town or village that he can visit, on business, or for amusement, without being exposed to the indignation of the inhabitants!

I have dwelt the longer on this particular, because it appears to me of singular importance.—The union which remarkably prevails through the Continent, at this alarming crisis affords great encouragement, and requires our thankful acknowledgments to almighty God.

It is our duty, as we love righteousness,–as we love peace,–as we love our Country,–as we love the parent state,–ourselves and millions of unborn posterity, it is our duty, to do all in our power, to strengthen and perpetuate, this union.—And was I not sure, you are ready even of yourselves, I would urge you my friends and fellow citizens, by arguments which influence my own mind, “To abide by and strictly adhere to the Resolutions of the continental Congress, as the most peaceable and probable method of preventing confusion and bloodshed, and of restoring that harmony between Great-Britain and these colonies, in which we wish might be established not only the rights and liberties of America, but the opulence and lasting happiness of the whole British Empire.” 14

I CANNOT finish this part of the discourse, without mentioning another reason the inhabitants of this Town in particular have for thankfulness, which, is a consideration of the unexpected liberality of our brethren towards us, since the Port has been shut up, by which thousands were reduced to poverty and distress.

Our condition would have been calamitous beyond expression, had not the hearts and the hands of our Brethren been opened to assist us, when suffering in the general cause.

We thank our generous benefactors: We thank the Father of the universe, for enabling and inclining them to do so much for us: And we thank those worthy Gentlemen, who cheerfully devote a great part of their time to take care of the money and provisions which are sent in from various parts, and make distributions to the needy among us, for no other reward, than the consolation of doing good.15

Thus have we attended to some of the blessings God is bestowing upon us in the course of his providence, which furnish us with proper reasons for praise and thanksgiving.

But as we are called, by the alarming situation of our public affairs, to sing of the judgments of the Lord, as well as of his mercies, we shall now, agreeable to the method proposed, take notice of the calamities which God has suffered to befall us.

The calamities to which we are more especially called to give our attention, are those which arise from “the present controversy between Great-Britain and the colonies.”

We are unhappy in being represented to the parent state as factious,–impatient of government, and wishing for independence; when “we can safely appeal to that Being, from whom no thought can be concealed, that our warmest wish, and utmost ambition is, that we and our posterity may ever remain subordinate to, and dependent upon our parent state. This subordination our reason approves, our affection dictates, our duty commands, and our interest enforces.”16

Great-Britain is possessed of a naval power, able to protect our trade, and guard our coast against a foreign enemy: And the colonies produce almost every article necessary to support the parent state in her present greatness, and add unspeakably to her future glory.

A CELEBRATED author, writing on the advantages which would naturally result from the happy connection between Great-Britain and the colonies, was no fatal interruption to prevent, has the following elegant and striking expressions.—“The immense advantages of such a situation, are worthy the closest attention of every Briton. To a man that has considered them with attention, perhaps it will not appear too bold to aver, that if an archangel had planned the connection between Great-Britain and her colonies, he could not have fixed it on a more lasting and beneficial foundation, unless he could have changed human nature.—An Alexander, a Caesar, a Charles, a Lewis and others have sought through fields of blood, for universal empire. Great-Britain has a certainty by population and commerce alone, of attaining to the most astonishing and well founded power the world ever saw. The circumstances of her situation are new and striking. Heaven has offered her glory and prosperity without measure. Her wise ministers disdain to accept them—and prefer” 1718

Since advantages of the most important nature might be derived to both countries were they to be perpetually united in affection, as they are in interest, how ardently is it to be wished, no unhappy controversy had arose between them.—But a controversy now subsists, which has a threatening aspect on America, and Great-Britain herself.

Many calamities are already felt, more and greater are much to be feared.—Instead of mutual love, and a desire of each others greatness, mutual jealousies are strongly exercised: The unfailing consequence of which will be, mutual endeavours to prevent each others interest. A principal of self preservation, that law of nature, which has an uniform influence on the children of Men, will excite them to wish the diminution of that power which they suppose, is at present engaged against them, or in some future time may rival them. And what they wish they naturally express, and will pursue in every measure that promises success.

And can it remain a matter of uncertainty, whether many in Great-Britain are jealous of the increasing greatness of the American interest, and wish to check the growth of the colonies, when we are told what opposition was made to the settlement of a new Province by a late minister of State.—When we hear another minister declaring he will lay the Americans at his feet.—When we hear with Application to one of the largest and most important Towns on the continent, “delenda est carthago”19 “We know how acceptable to many an earthquake would be to sink some of the colonies in the Ocean.—That we are thought too numerous. And how much it would be judged for the interest of Great-Britain, if a Pestilence should sweep off a million and a half of us.” 20

If Great-Britain is jealous of the increasing interest of the colonies, no doubt she will exert her power to check their growth, or her policy to draw off their riches as fast as they acquire them. And from the measures which have been pursued, with unremitting zeal for several years past, the Americans are made to believe, that Great-Britain does not wish the Colonies to make further advances towards “powerful States.”—The business then is to embarrass new settlements,–to lay such burdens on the colonies now planted as to prevent emigrations to them from the crowded parts of Europe, and establish such laws as shall render, not only the money, but the persons of Americans, the property of the British Parliament, or of the crown. 21

And should I say, this business has been earnestly pursued, “since the close of the late “war”, I should have the authority of the greatest and best men in the nation,–I should have more than nine-tenths of America to support the assertion.

The execution of this business has given rise to the calamities, we are this day called to lament.—The time would not allow us to go into a very particular consideration of the calamities we now feel, together with those which we tear may be permitted to fall upon us: Let it suffice to mention those which most sensibly affect us.

Several laws, have of late been enacted by the Parliament of Great-Britain, for the express purpose of raising a revenue in America. Had hose laws been executed according to their original design, the natural operation of them, would have constantly weakened the interest of the people in general, by giving their wealth to the servants of the crown.—Had those laws been regularly executed the servants of the crown, would have had it in their power, either to riot on the spoils taken from the honest and industrious, or accumulate to themselves great riches. The body of the people, being oppressed, would in time be obliged to sell their lands, and other estates, and content themselves, if contentment be possible in such a state, to be the slaves of imperious lords, on whom, hard necessity had taught them to depend, for their bread.—And should they, remembering their former happy circumstances, grow uneasy and factious, a standing army, supported by money taken from them, would be ready to humble, or destroy them.—Figure to yourselves all the calamities which are felt by the inhabitants of France and Spain, or other parts of the World where despotism is established, and I will be bold to say, we could have no security against calamities equally great, unless in the virtue of the reigning Prince, were the laws which have been passed, with respect to America, since the last war, fully carried into execution.

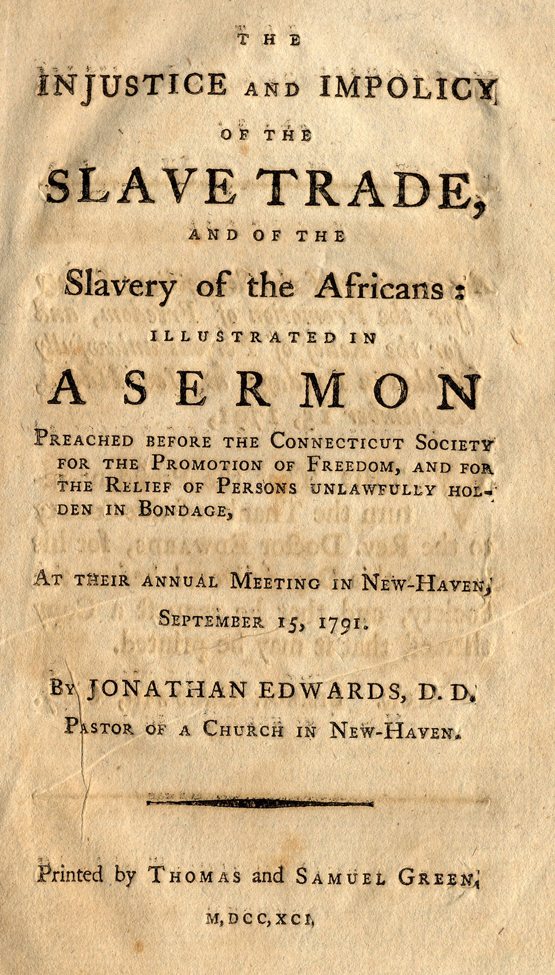

If the British Parliament, may “of right,” without our consent, “give and grant” any particular parts of our property, for any particular purposes, they may the whole: They say with equal pretentions to right sell our persons as slaves to what masters they please. For “Liberty, Life, or Property, can, with no consistency of words or ideas, be termed a right of the possessors, while others have a right of taking them away at pleasure.” 22

That such laws have been enacted, and that any of them are now in force, we consider as a calamity, and lament that God has in judgment, suffered it to befall the American colonies.—The laws now referred to, have already done unspeakable damage. The struggles which have been made by administration to enforce them, and by the Americans in opposition to them, have not only kept the whole continent in a ferment, but created such an alienation of affections, and unhappy jealousies between the two countries, as we have reason to fear, will never be wholly removed.

It is a calamity that the parliament have resolved, “That colonists may be transported to England, and tried there upon accusations for treason,–or concealments of treasons committed in the colonies.”—Should any unhappy Americans be accused of treason, and prosecuted according to this act, a severe punishment would necessarily be inflicted on them, before it could be determined whether they were guilty or not.

It is a calamity that the Roman Catholic religion is established through the vast province of Quebec, when, as a writer observes, “The abject of the bill, is to cut off all liberties of the rest of the colonies.” 23

Should that vast country which is now taken into the province of Quebec, be filled up with roman Catholics, who are by their religion unfriendly to protestants, and especially to dissenters, it may be in their power, assisted by the Indians to do unspeakable damage to the other colonies. We may easily conceive it will be extremely difficult for Protestants, who now have possessions in that part of the world, to live quietly, or for others to settle where the established religion teaches its professors, that they may violate the most solemn engagements with heretics, and exterminate them from their country when it can be done with safety.

We view it as a calamity, that, by the Lords spiritual, that venerable Bench of protestant Bishops, a warm opposition was not made to a bill brought in to establish a Religion in the most important colony of his Majesty’s dominions, which has disgraced humanity, and crimsoned a great part of the world, with innocent blood.

By the part which the venerable seat of Bishops took in the Canada act, the unparalleled sufferings of our ancestors, by the influence of some protestant Bishops, 24 in former Reigns, are brought fresh to view: And we cannot but apprehend, a foundation is laid, for like ecclesiastical tyranny, at least, in the province of Quebec, should a prince of arbitrary sentiments, hereafter be placed on the throne.

We view it as a calamity, that our most gracious King was pleased to give his royal assent to the Canada Act, by which he has grieved the greatest part of his faithful subjects.—But I forbear.—That unfortunate Prince, who was obliged to fly from Great-Britain, to make way for the Hanoverian succession, was charged among other things, with promoting the Roman Catholic Religion—May the reign of our present rightful Sovereign be long and happy.—May he ever enjoy the full confidence, and affection of all, and especially of his protestant subjects.

We view it as a calamity, that the Parliament have passed an act to alter our ancient method of appointing Juries.—With a Governor and Council entirely dependent on the crown: With Judges and Sheriffs dependent on the Governor, and all entirely independent on the people, we cannot suppose there is provision for the impartial administration of justice: But we have the greatest reason to fear, should any Americans be so unhappy, as to be brought into dispute with crown officers, or any, who on account of their good disposition towards some late acts of Parliament respecting the Colonies, are called friends of Government, a jury returned by such sheriffs, would be under an influence, extremely threatening to the lives and liberties, of such unfortunate subjects.

The noble Lords who entered their dissent, have given a reason, which has respect to this part of the Act for regulating the government, sufficient to convince every mind capable of seeing the force of argument, and is worthy to be writ in letters of gold.—They dissent,–“Because the Governor and Council have the means of returning such a Jury, in each particular cause, as may best suit with the gratification of their passions and interests. The lives, liberties and properties of the subject are put into their hands without control, and the invaluable right of trial by jury is turned into A SNARE FOR THE PEOPLE, who have hitherto looked upon it as their main security against the licentiousness of power.” 25

We view it as a calamity that the British Parliament have lately passed “an Act for regulating the government” of this Province, by which the most important rights of our character are violated, and the way is prepared for exercising an arbitrary and despotic government over us.

Attempts to execute this act have already flung the Province into great disorder.—The inhabitants consider their charter, granted on the faith of Kings, as sacred, and they cannot be prevailed with, either by flattery or threats, to give it up.—Those Gentlemen who have accepted the place of Counselors on the new plan, are viewed as unfriendly to our constitutional liberties:–Our Courts of Justice are shut up: And we are nearly reduced to a state of nature,–In short we have no security for life, or property, or any of the blessings of society, but from the virtue and resolutions of the inhabitants in general.

“To change the government of a people”, says the Bishop of St. Asaph, who is an honour to the sacred order, and an ornament to human nature,–“to change the government of a people without their consent, is the highest and most arbitrary act of sovereignty that one nation can exercise over another. The Romans hardly ever proceeded to this extremity, even over a conquered nation, ‘till its frequent revolts and insurrections, had made them deem it incorrigible.—The very idea of it implies a most total and abject, slavish dependence in the inferior state.”

That great and good man well knew, that attempts to change the government of this province, would be productive of the utmost confusion:–“It will make them mad”.

The noble Lords, who opposed the bill for regulating the government of this Province, entered their dissent,–“Because, say they, we think the appointment of all the members of the Council, which by this bill is vested in the crown, is not a proper provision for preserving the equilibrium of the colony constitution. The power given to the crown of occasionally increasing and lessening the number of the council on the report of governors, and at the pleasure of ministers, must make those governors and ministers masters of every question in that assembly, and by destroying its freedom of deliberation will wholly annihilate its use.”—

But the calamities arising from the unhappy controversy at present subsisting between Great-Britain and America, with which we, the inhabitants of this town, are most sensibly, and in a peculiar manner affected, are yet unnoticed.

When we look back, on our once happy state, and compare the blessings of peace and plenty, which we freely enjoyed, with our present distresses, “the tears are on our cheeks”. “How doth the city set solitary that was full of people! How is she become as a widow! She that was great among the nations, and princess among the provinces, how is she become tributary! 26

The God of nature has taught us by the situation and uncommon advantages of this place, that it was designed for extensive business: And here our fathers planted themselves, that they and their posterity might prosecute those branches of trade and merchandise, which give riches and strength, to nations and states.—And this, for many years, has been the peaceful residence of commerce and wealth.

What joy have we felt to see this capacious and safe harbor, white, with the canvass of our own ships, or of foreigners who came to exchange their treasures, for the commodities which we had to spare.

But how affecting is the change; How gloomy is the present appearance!—Look to our port, and you see it blocked up with British Ships of war—No vessels of trade are allowed to enter this harbor.—Commerce which gave wealth to many, and the means of a comfortable subsistence to thousands, has now ceased.—The well built wharfs are either left naked, or lined with transports, which have been employed to bring the King’s troops to this place.—Stores which were designed for merchandise, are, either unoccupied, or strange to relate!—turned into barracks!—Our public streets,–our most pleasant walks are filled with armed soldiers.—The only avenue to the town by land is fortified on each side, with heavy cannon, and strongly guarded day and night.—In short, all things wear the shocking appearances of war: Of war, not with the natives of the wilderness, or those foreign enemies with whom we have formerly engaged with success.—But,–how shall I speak?—Of war between Great-Britain and the colonies!—Between fellow subjects!! Between brethren!!!

But why these strange appearances? Why is the power of Great-Britain so unnaturally directed against America?—Why is this Town filled with troops? Why is this port blocked up, and the trade of the place ruined?—certainly we must have been guilty as a people of the most daring crimes.—Nothing less than an open and generally avowed rebellion against the best of Princes, one would think, could justify such treatment.—Have we been thus guilty?—Are we, thus charged?—No.—What then is our crime?—It is not pretended to be any more than a trespass, committed by some unknown persons, on private property.—Because a number of people, we know not who, destroyed some cargoes of East-India Tea, this whole community has been condemned, without trial, and is this day suffering in a manner that can scarcely be paralleled in the history of the world.

It is supposed by the rigorous manner in which the port act is executed, poverty, distress and calamity, are brought on 30,000 souls. 27

Other calamities might have been mentioned, and those we have taken notice of enlarged upon, did the time admit.—You will just allow me to say, should the British administration determine fully to execute the laws, of which we complain: Or in other words,–should the prime minister determine to LAY THE AMERICANS AT HIS FEET; and should the new parliament grant supplies for that purpose, we have yet to fear the calamities of a long civil war: For, from the spirit now raised through this continent, and the firm union which subsists, it may be presumed he struggle would be obstinate.

Americans, who have been used to war from their infancy, would spill their best blood, rather than “submit to be hewers of wood, or drawers of water, for any ministry or nation in the world”. 28

But we hope in God, and it shall be our daily prayer, that matters may never come to this.—We hope some wise and equitable plan of accommodation may take place.—For the salvation of the parent state, as well as of these provinces, we sincerely hope the measures, with respect to America, adopted by the last parliament, and pursued with vigour by the ministry, may be essentially altered by this.

We hope the rights and liberties of the colonies may be established on a solid and immoveable basis: And that this Town may emerge from its present distressed and most calamitous state, and be a more prosperous, more rich and happy place than ever yet it has been.

Let us then humble ourselves before God on account of our sins: Let us reform whatever is amiss,–“That so God may be pleased to continue to us the blessings we enjoy, and remove the tokens of his displeasure, by causing harmony and union to be restored between Great-Britain and these Colonies, that we may again rejoice in the smiles of our sovereign, and the possession of those privileges which have been transmitted to us, and have the hopeful prospect that they shall be handed down entire to posterity, under the protestant succession, in the illustrious House of Hanover.”29

FINIS.

Endnotes

1 Exodus 34. 22.

2 See the recommendation from the Provincial Congress, for a day of thanksgiving.

3 Henry on the place.

4 John 3. 16.

5 Luke 2. 14.

6 James 4. I.

7 Phillip. 3, 21.

8 See the History of England during the Reigns of the Stuarts.

9 The following extract from an Act “passed by the Great and General Court” of this province, “to exempt the People called Quakers, and Antipedobaptists, from paying Taxes for the support of Ministers settled by the Laws of this Province, and for the building and repairing Meeting Houses or places of public Worship,” may serve to evince what was said above with respect to religious liberty, and the tenderness which is exercised towards such as dissent from the mode of worship and discipline established by law.

Be it enacted by the Governor, Council, and House of Representatives, that none of the Persons who are either of the Persuasion of the People called Quakers, or Antipedobaptists, who allege a scruple of Conscience as the reason of their refusal to pay any part or Proportion of such Taxes, as are from time to time assessed for the Support of the Minister or Ministers of any Church settled by the Laws of this Province, shall have their Polls or Estate, Real or Personal in their own Hand, and under their actual Improvement; taxed or assessed, in any Tax or Assessment hereafter made for the raising any Monies towards the Settlement or Support of such Minister or Ministers, nor for building or repairing any Meeting-House or Place of public Worship, or be obliged to collect any Taxes granted for the purposes aforesaid.

And to the intent that it may be better known who are to be exempted by this Act.

Be it enacted, That no Person in any Town, District or Precinct in this Province, shall for the future be esteemed or taken to be of the Persuasion of the People called Quakers, or Antipedobaptists, so as to have his, her or their Poll or Polls, or any Estate to him, her or them belonging, exempted by virtue of this Act from paying a proportionable Part of the Ministerial or other Taxes in this Act mentioned, but such whose Names shall be contained in a List or Lists taken and signed by three Members of some Quaker or Antipedobaptist Society or Congregation, who shall be chosen by said Society or Congregation, who shall be chosen by said Society or Congregation for that purpose; one whereof to be the Minister where there is any, who shall therein certify for substance with respect to the People called Quakers in the form following, viz. We the Subscribers being chosen a Committee by the Society of the People called Quakers, who meet together for religious Worship on the Lord’s Day or first Day of the Week in (blank space) to exhibit a List or Lists of the Names of such Persons as belong to said Society or Congregation, do Certify, that (blank space) do belong to said Society or Congregation, and that they do frequently and usually when able attend with us in our Meetings for religious Worship on the Lord’s Day or first Day of the Week, and we verily believe are of our Persuasion.

Dated Signed A. B., C. D., E. F.; Committee.

And with respect to the Antipedobaptists in the words following, viz. We the Subscribers being chosen a Committee by the Society of the People called Antipedobaptists, who meet together for religious Worship on the Lord’s Day in (blank space) to exhibit a List or Lists of the Names of such Persons as belong to said Society or Congregation, do Certify, that (blank space) do belong to said Society or Congregation, do Certify, that (blank space) do belong to said Society or Congregation, and that they do frequently and usually when able attend with us in our Meetings for religious Worship on the Lord’s Day, and we do verily believe are, with respect to the ordinance of Baptism, of the same religious Sentiments with us.

Dated Signed A. B., C. D., E. F.; Committee.

Which Certificate so signed, the said Committee shall cause to be delivered to the Town, District or Precinct Clerk respectively, where such Person or Persons contained in such List or Lists dwell or have Estates liable to be taxed, on or before the first Day of September Annually; and the Clerk on receiving such Certificate, shall enter the same at large in the Town, District and Precinct Book in his keeping, with the time when the same was delivered to him, and shall deliver an attested Copy of such Certificate and the time when the same was delivered to him, to any Person desiring the same, receiving therefor, four Pence only, which Copy shall be received as Evidence on any Tryal respecting the Taxing the Persons whose Names are contained in said Certificate for any Ministerial Charge or Charges, or for building or repairing any Meeting-House.

10 The following Regiments are now Stationed at Boston, and at Castle-William.—Fourth Battalion of the Royal Regiment of Artillery.—Fourth (or King’s own) Regiment.—Fifth Regiment.—Tenth Regiment.—Eighteenth (or royal Irish) Regiment. Twenty-Third-Regiment, Or royal Welch Fusileers.—Thirty-Eighty Regiment.—Forty-Third Regiment.—Forty Seventh Regiment.—Fifty Second Regiment.—Fifty Ninth Regiment.—Sixty Fourth Regiment.—Sixty Fifth Regiment.—We have also the following large Ships of War,–Preston, of 50 Guns. Somerset, of 68. Asia, of 64. Boyne, of 64: Besides a number of smaller Ships and other armed Vessels; together with the Transports which have been employed to bring Troops to this unhappy Metropolis.–

11 See the Pennsylvania Instructions to their Representatives.

12 Proceedings of the American Congress, P. 2.

13 Essay on the constitutional Power of Great-Britain over the Colonies in America.

14 See the Address of the Provincial Congress, presented to the several Ministers of the Gospel in this Province.

15 Some evil minded persons, have wickedly insinuated, that the Committee, with whom the donations are entrusted, and by whom they are distributed to such as stand in need, take pay for their trouble, or they would never devote so great a part of their time to the service.—This insinuation is equally false and malicious.—Those respectable Gentlemen have indeed the thanks of the public, and the blessing of many ready to perish; besides which they neither have nor wish for any reward—is it not base and cruel then, to insinuate, as some have done, that they pay themselves out of the charities which were designed for the immediate sufferers.

But some people have a scurvy trick of lying, to support a certain interest, and if possible injure those who are most faithful and unwearied in the service of their country.—But great is truth, and it will prevail.

16 Essay on the constitutional power of Great-Britain over the colonies in America, p. 52.

17 See the Note in the same Essay, pp. 56, 57.

18 Mr. Nugent’s Speech.

19 Which is to be interpreted, let Boston be demolished. The sage advice of Mr. Van a member of the late parliament.

20 Essay on the constitutional power of Great-Britain &c. p. 61.

21 “The authority of Parliament, has, within these few years, been a question much agitated; and great difficulty, we understand, has occurred, in tracing the line between the rights of the mother country, and those of the colonies. The modern doctrine of the former is truly remarkable; for though it points out, what are not our rights, yet we can never learn from it, what are our rights. As for example—Great-Britain claims a right to take away nine-tenths of our estates—have we a right to the remaining tenth? No.—To say we have, is a “traitorous position”, denying her supreme legislative. So far from having property, according to these late found novels, we are ourselves a property”.

See Essay &c. p. 33, 34.

22 See Essay &c. 41. See Locke on Government. Chap. V. “What property have they in that, which another may by right take, when he pleases to himself?” Mr. Pitt’s Speech.

23 The Canada Act has met with some small advocates in these parts, who pretend the roman catholic religion is not established by it; and that nothing more is designed by that part of it which has respect to religion, than a confirmation of what was stipulated by the treaty of peace.—But what say the Grand American Congress to this matter?—“In the session of Parliament last mentioned, an Act was passed, for changing the government of Quebec, by which Act the Roman Catholic religion, instead of being tolerated, as stipulated by the treaty of peace, is established.”

The Earl of Chatham has declared, that by the Canada Act, popery is established: And Lord Lyttleton, in his Letter to the above-mentioned Earl, does not deny that the Roman catholic religion is established in the Province of Quebec, but endeavours to defend the whole Act, without exception.—After having said, “The Canadians are “above one hundred thousand, the English not more than two thousand men, women, and children.” And that the legislature was therefore to consider whether the law and government ought to be adapted to the many or the few,” he goes on, to consider that part of the bill which has respect to religion; and says,–“The best distinction I know between establishment and toleration is, that the greater number has a right to the one, and the lesser to the other. The public maintenance of a clergy is inherent to establishment; at the reformation, therefore, as much of the church estates as were thought necessary for its support were transferred to the protestant church, as by law established. Surely then when the free exercise of the national religion was given to the Canadian nation, it could never b understood that they were to be deprived of their clergy; and if not, a national provision for that clergy follows of course.”’.—What we have here quoted from his Lordship’s Letter, is sufficient to shew, that he not only considered the Canada Act as establishing the Roman catholic religion in that country, but that he supposed the British Legislature, acted a wise and equitable part in so doing.—But his Lordship’s reasoning does not carry with it the fullest conviction.—Suppose, by a strange Jesuitical influence, in some future period, more than one half the inhabitants of Great-Britain should be converted to the Roman catholic religion, would the legislature be bound in duty to establish that religion, and only tolerate Protestants?—It must be so, it seems, if the best distinction between establishment and toleration is, that the greater number has a right to the one, and the lesser to the other.

Wise legislative bodies, will examine the nature and doctrines of a religion, before they favour it with an establishment; If they find the doctrines of any religion are contrary to that the holy Scriptures, and are persuaded that it is, in its nature, unfriendly to the safety and happiness of the community, certainly they will not establish it, although, the greater number, (of the community) may, at present, be fond of it.—

Let us hear what the learned and pious Bishop Burnet has said of Roman Catholics, and their religion.—“It is certain, that as all Papists must, at all times, be ill subjects to a protestant Prince, so that is much more to be apprehended, when there is a pretended Popish heir in the case.”—“learn to view popery in a true light, as a conspiracy to exalt the power of the clergy, even by subjecting the most sacred truths of religion to contrivances for raising their authority, and by offering to the world another method of being saved, besides that prescribed in the gospel.—Popery is a mass of impostures, supported by men, who manage them with great advantages, and impose them with inexpressible severities, on those who dare call anything in question that they dictate to them.”

Bishop Burnet’s History of His Own Times. If the Roman Catholic religion is what the good Bishop has here declared, is it not astonishing, that any Protestant can plead for its establishment! For a British legislature to tolerate such a religion, is as much, one would think, as they could do consistent with their duty to God, and to that constitution of civil government, which they are bound to maintain.—

It may be said a religion is established, where there are laws for the support of it.—Thus is the church of England established in a great part of the British dominions.—Thus are the congregational order and discipline established in this Province, and thus is the roman catholic religion established in Canada.

24 The high Church party says Bishop Burnet, have all along been unfriendly to the government established on revelation principles: They have not been wanting to reproach those who were of moderate sentiments, and abuse the dissenters,–Why? Because moderate church-men and Dissenters in general, have been friends to the rights of mankind, and honest enough to oppose Tyrants in church and state. I would here beg leave to insert a paragraph from a Pamphlet which fell into my hands since this discourse was delivered, called, An address to Protestant Dissenters of all Denominations &c.—“The measures that are now carrying on against the North-American colonies are alone a sufficient indication of the disposition of the court towards you. The pretence for such outrageous proceedings, conducted with such indecent and unjust precipitation, is much too flight to account for them. The true cause of such violent animosity must have existed much earlier and deeper. In short, it can be nothing but the Americans (particularly those of New-England) being chiefly dissenters and whigs. For the whole conduct of the present ministry demonstrates, that what was merit in the two late reigns, is demerit in this. And can you suppose that those who are so violently hostile to the offspring of the English dissenters, should be friendly to the remains of the parent stock? I trust that both you and they will make it appear, that you have not degenerated from the principles and spirit of your illustrious ancestors, and that you are no more to be outwitted or overawed than they were.”

25 Much to our purpose is the following extract from Doctor Pettingal’s celebrated Enquiry into the use and practice of Juries among the Greeks and Romans.

“The privilege that every Englishman enjoys of having his person and property so far secured, that no injury, under pretence of law can be done to one or the other, but by the consent and approbation of twelve men of his own rank, is the greatest happiness that can belong to a subject, and the most valuable blessing that can attend society; for by this means the poor stands in no fear of oppression from his governor or powerful neighbour; and the hands of the great are tied up from disturbing the public by making inroads upon the ease and property of individuals below them.—So that the powers of each, in their respective stations, are hereby happily directed to carry on one and the same end, the peace, order, and good government of the whole.”

In another place the same great Man writes,–“The trial by Jury was founded on liberty, and contrived both in the Grecian and Roman polity, as a guard and protection of the lower people, against the power and arbitrary judgments of their superiors.”—And again, “Civil liberty, being thus, both in Greece and Rome, founded in equality, that is, a joint power and participation of enacting and executing laws, we hence see the reason why the trial by our equals, the legale judicium parium suorum, makes so great a figure in the character of English liberties; for while we are bound by no laws but those we consent to, and suffer no judgment under those laws but by the approbation of honest men of our own rank and condition, who have no interest in injustice, but an expectation of the same candor and integrity in us upon some other occasions, where perhaps we may be a jury on them or their affairs, there is no danger of being ruined and undone by arbitrary laws, or oppressed by the partial determination of a corrupt Judge. This was the liberty and happiness that arose from the equality which was the foundation of the Greek and Roman constitution, and is the very spirit and life of our own.”—p. 8. In Preface, I. 25, & 26, in the Enquiry.–

26 Lamentations Chap. I. I.

27 The damages arising from the execution of the Port Act are immense: Supposing 30000 people suffer the loss of 1S sterling per day, one with another; which I believe will be judged far short of what is real, considering the destruction of Trade,–the multitudes flung into idleness,–the useless condition of shipping, Wharfs, Stores, Ware-Houses &c. And the damages the last Six months will be 270000 pounds Sterling.

28 See the address of the American Congress to the People of Great-Britain.

29 See the recommendation from the Provincial Congress for a day of thanksgiving.

also spelled Lothrop, was born in Norwich, Connecticut. He graduated from Princeton in 1763 and began working as an assistant teacher with the Rev. Dr. Eleazar Wheelock of Lebanon, Connecticut, at Moor’s Indian Charity School. He studied theology under Dr. Wheelock (who later founded Dartmouth College) and became licensed to preach in 1767, ministering among the Indians. In 1768, he became the preacher of the Second Church of Boston, but as Boston was central in the rising tensions and violence with the British leading up to the American War for Independence, he relocated to Providence, Rhode Island. When the Founding Fathers declared independence from Britain in 1776, Lathrop returned to Boston. When Dr. Pemberton of New Brick Church was taken ill, Lathrop was asked to become the assistant to the pastor. When Pemberton passed away a year later, Lathrop became pastor of New Brick Church but also retained the pastorate of Second Church, merging it into New Brick in 1779. Lathrop remained pastor until his death from lung fever in 1816. He had served as President of the Massachusetts Bible Society and the Society of Propagating the Gospel in North America, and he was also a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Antiquarian Society. Numerous of his sermons were published, including the following one delivered on December 15, 1774.

also spelled Lothrop, was born in Norwich, Connecticut. He graduated from Princeton in 1763 and began working as an assistant teacher with the Rev. Dr. Eleazar Wheelock of Lebanon, Connecticut, at Moor’s Indian Charity School. He studied theology under Dr. Wheelock (who later founded Dartmouth College) and became licensed to preach in 1767, ministering among the Indians. In 1768, he became the preacher of the Second Church of Boston, but as Boston was central in the rising tensions and violence with the British leading up to the American War for Independence, he relocated to Providence, Rhode Island. When the Founding Fathers declared independence from Britain in 1776, Lathrop returned to Boston. When Dr. Pemberton of New Brick Church was taken ill, Lathrop was asked to become the assistant to the pastor. When Pemberton passed away a year later, Lathrop became pastor of New Brick Church but also retained the pastorate of Second Church, merging it into New Brick in 1779. Lathrop remained pastor until his death from lung fever in 1816. He had served as President of the Massachusetts Bible Society and the Society of Propagating the Gospel in North America, and he was also a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Antiquarian Society. Numerous of his sermons were published, including the following one delivered on December 15, 1774.