John Lathrop (1740-1816) Biography:

John Lathrop (1740-1816) Biography:

John Lathrop, also spelled Lothrop, was born in Norwich, Connecticut. He graduated from Princeton in 1763 and began working as an assistant teacher with the Rev. Dr. Eleazar Wheelock of Lebanon, Connecticut, at Moor’s Indian Charity School. He studied theology under Dr. Wheelock (who later founded Dartmouth College) and became licensed to preach in 1767, ministering among the Indians. In 1768, he became the preacher of the Second Church of Boston, but as Boston was central in the rising tensions and violence with the British leading up to the American War for Independence, he relocated to Providence, Rhode Island. When the Founding Fathers declared independence from Britain in 1776, Lathrop returned to Boston. When Dr. Pemberton of New Brick Church was taken ill, Lathrop was asked to become the assistant to the pastor. When Pemberton passed away a year later, Lathrop became pastor of New Brick Church but also retained the pastorate of Second Church, merging it into New Brick in 1779. Lathrop remained pastor until his death from lung fever in 1816. He had served as President of the Massachusetts Bible Society and the Society of Propagating the Gospel in North America, and he was also a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Antiquarian Society. Numerous of his sermons were published.

A

DISCOURSE,

DELIVERED IN BOSTON, APRIL 13, 1815,

THE DAY OF THANKSGIVING

APPOINTED BY THE

PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES

IN CONSEQUENCE OF THE

PEACE.

BY JOHN LATHROP, D. D.

PASTOR OF THE SECOND CHURCH IN BOSTON.

SERMON.

1st BOOK OF CHRONICLES, XVI. 8,9.

“Give thanks unto the Lord, call upon his name make known his deeds among the people. Sing unto him, sing psalms unto him, talk you of all his wondrous works.”

NEVER, my friends, did we assemble with more cheerful hearts to offer praise and thanksgiving to Almighty God, than we do on the present occasion. Never have we witnessed joy more universal than the joy expressed by the American people at the return of peace. This event, like the sun breaking from a cloud, hath scattered the darkness which hung over our afflicted country, and given new spirits and new life to many who were “bowed down to the dust,” and “covered with the shadow of death.”

On such an occasion, it is highly proper, that people professing the Christian religion, do assemble in places of worship, and offer praise and thanksgiving to Him who ruleth over the nations, and turneth the hearts of the kings, and of the mighty men of the earth, as the waters are turned.

Not only the people of our country but the greatest part of the Christian world, have been in deep affliction. Modern history presents no period to our recollection, in which the miseries of war have been more generally felt, than during the last few years; and it is with great pleasure that we hear, peace was no sooner restored to the bleeding nations of Europe, than the temples of the Most High were filled with praises and thanksgivings.

As the American people were the last to take the cup of affliction, which the Sovereign of the world hath caused to pass from one nation to another, so are they the last, but we trust, not the least, in sincere and humble gratitude, to the giver of all mercies for granting salvation to many millions of people, by a general peace.

The text points out to us a course of exercises, proper on the present occasion. We are called upon by a sense of gratitude; by a recollection of the benefits which a merciful God hath bestowed upon us, – we are called upon to give thanks, – to worship Him, – to talk of all his wondrous works.

It would be pleasant, and it would be useful, to talk of those wondrous works which proclaim the Eternal Power and Godhead; and which have called forth the reverence and love of the wise and good, in all parts of the world. By the things which our eyes behold, we have convincing evidence, that a Being of infinite perfection, presides over the universe and guides all the movements of it, according to his pleasure. But on the present occasion, we feel disposed to talk more particularly of the loving kindness and of the mercy, which God was pleased to show to the Fathers of our Country; of the protection grated to them and their children, in seasons of weakness and danger, and when they were exposed to the savages of the wilderness, and to other powerful enemies; – of the wars in which our country has been engaged; – of the late war, and of the peace which God hath now given to us. From a review of the wondrous works of mercy and goodness, “which were done in the times of old,” and which have been done in later years, we will endeavour to excite those grateful and pious feelings, which alone can render our public expressions of thanksgiving acceptable to a gracious Benefactor.

When we speak of the Fathers of our Country, we have respect to those Europeans, who early adventured to this quarter of the world, and made settlements in various parts of the extensive region now called The United States of America : but when we speak of the Fathers of New England, we have respect to those protestant Christians, who, having been oppressed and persecuted by a race of despotic sovereigns, and by an intolerant hierarchy, left “the places of their fathers sepulchers,” and made the first permanent settlements, in the region which we inhabit, and which still bears the name of the country from whence they emigrated.

The views of the early adventurers to North America, even from Columbus in 1492, to the time when the pilgrims landed at Plymouth, in 1620, where extremely various. The object of some of them was, discovery. — Men best acquainted, in those times with the principles of geography, expected to find a passage to India, by the Western Ocean. Others were excited to the hazardous undertaking, and made voyages to this quarter of the world, with the expectation of wealth: reports were spread abroad, that on the islands and on the continent there was plenty of silver and gold. But it was for the express purpose of securing for themselves and for their children the rights of freemen, and more particularly the rights of conscience, that the Fathers of New England exchanged their dwelling places, in a country abounding with the means of subsistence, for a wilderness, where wants and sufferings were to be expected.

The first Christian pilgrims approached these northern shores at an inclement season of the year. At their landing they found no shelter from the cold and from the tempest. They were in want of those refreshments which would have been peculiarly grateful after the fatigues and dangers of a long voyage. By reason of the privations and the sufferings, which were unavoidable in their miserable habitations, they soon became sickly; and before the opening of the spring, forty-five of the one hundred and one, who landed on the last of the preceding December, were dead.

Although the first Christian pilgrims had been brought to this northern region, contrary to the contract which they had been careful to make before they left their native country, divine providence seems to have prepared a place for them, in which they might plant themselves without any immediate opposition. The Indians, who had before inhabited the ground on which they landed, and the wilderness bordering on them were nearly extinct. The had some time before been beaten in bloody wars with other savage nations; and, to complete their destruction, an awful pestilence had raged among them, sweeping away both the old and the young, until it might be said, “The land was left without inhabitants.” With great propriety we quote and apply a part of the XLIV. Psalm. — “We have heard with our ears, O God, our fathers have told us, what thou didst in their days, in the times of old. How thou didst drive out the heathen with thy hand, and plantedst them : how thou didst afflict the people and cast them out. For they got not the land in possession by their own sword, neither did their own arm save them; but thy right hand, and thine arm, and the light of thy countenance, because thou hadst a favour unto them.”

The feeble pilgrims, at the first, had indeed no enemy to oppose them. None of the original lords of the soil came to protest against their landing. The first visit made them by an Indian, was in the month of March. One of the chiefs of a tribe, living a considerable distance, appeared, unexpectedly; and in their own language which he had imperfectly learned from Europeans, who had visited the country, he addressed them saying, “Welcome, Englishmen; Welcome, Englishmen!”1

The fathers of New England were not, however, permitted to continue many years unmolested. The tribes of Indians, who inhabited the vast wilderness, observing the increase of English settlements, and hearing of the arrival of new adventurers, indulged suspicions, that the strangers, who were not only spreading along on the sea shore, but were extending into the country, would, ere long, compel them to relinquish the possessions which their fathers had enjoyed, from time immemorial.

Jealousies and apprehensions, such as we have no mentioned, were greatly strengthened by the intercourse which the natives of the wilderness had afterwards with the French, whose settlements were progressing in Nova Scotia and in Canada. The most dangerous wars in which the fathers of New England were engaged, are traced to the sources which we have now mentioned. Philip, son and successor of Massasciet, the historian observes, “could not bear to see the English of New Plymouth, extending their settlements over the dominions of his ancestors; and although his father had, at one time or another conveyed to them all that they were possessed of, yet he had sense enough, to distinguish a free voluntary covenant, from one he made under a sort of duress; and he could never rest until he brought on the war, which ended in his destruction.” The same historian adds; “The eastern wars have been caused by the attachment of those Indians to the French, who have taken all opportunities of exciting them to hostilities against the English.”2

During the wars with Philip, and with various tribes of Indians, after the death of Philip, assisted by the French from Canada and Nova Scotia, the New England Colonies, more especially Massachusetts and New Hampshire, were exposed to great sufferings. Such was the influence which Phillip had over his own tribe, and over many other tribes of the savages that he was able to send the calamities of war to almost every town in New England. Many innocent people were killed while laboring in their fields; many women and children were killed in their houses; many were taken and carried away into captivity. Between the month of June 1675, when this noted warrior began his work of murder and depredation, and the month of August, 1676, when he fell in battle, many of the towns in this then colony, which are now beautiful and opulent, were visited by the savage invaders, and either in whole, or in part were destroyed. I will mention some of them. — Brookfield was among the first, seven days after was laid in ashes. Springfield, partly destroyed. Groton, wholly destroyed. Lancaster, and Medfield, and Warwick, and Sudbury, and Marlborough, and Chelmsford, and Weymouth, and Bridgewater, and Scituate, and Middleborough, and Plymouth, and several other towns, were attacked, and in most cases some of the inhabitants were killed, and some carried into captivity; and many of the buildings left in flames.

Nor did the work of devastation and murder end with the death of Phillip.3 Expeditions were made from Canada and from Nova Scotia. Saco, and Wells, and York, and Dover, and Berwick, and other places, were invaded by French and Indians from the east. Many people were killed, and many houses were destroyed. Several towns, which were destroyed in the time of Philip’s war were again visited and destroyed by parties of French from Canada, and the Indians who united with them. So late as 1704, Deerfield was again invaded and burnt; many of the people were killed, and their minister, Rev. Mr. Williams was carried into captivity. And four years after, Haverhill was attacked, and in part burnt; Rev. Mr. Rolfe the minister of the town, and thirty or forty of the people were killed.

During the long reign of Lewis XIV king of France, great exertions were made by that monarch to gain an ascendency over the powerful kingdoms of Europe, and, in the end, make all of the nations of the world bow to his authority. He found the English were making settlements on the atlantick coasts, and rapidly extending their borders into a country capable of high cultivation, and promising a lucrative commerce. He, too, had colonies in North America; but he had an impression, that his colonies would be of but little advantage to him, unless he could prevent the growth of the English colonies, but eventually, would have extirpated them. We find a plan for the purpose now mentioned, adopted by the court of France, as early as 1687.4

The French project to obtain, and to hold the dominion of all North America, was simple, while it was deep. It was to secure the great rivers at the north east, and at the south west, viz. the St. Lawrence, and the Mississippi, as well as the inland seas, which complete the line of water communication, and which give facility to an immense commerce. They very well knew, that the power, which shall be able to command on those waters, will be able to command and to direct the numerous tribes of savages who inhabit the vast wilderness between the English colonies and the French settlements. To carry this plan in to effect, we find the French exploring the waters of the Mississippi, in the year 1687. Some years after, we hear of them making settlements on the borders of that river. We hear of them erecting forts, at the most commanding places, near the lakes, and other navigable waters at the west; and at the same time, making unreasonable demands of territory at the east.5

Having thus prepared, the French lost no time in attempting to carry their plan into execution. They availed themselves of the jealousies which already existed in the minds of many of the native Indians, that the English would take from them their hunting grounds, and destroy them. In this state of jealousy and irritation, they were excited to deeds of savage cruelty. They not only invaded the frontier settlements, and penetrated the country, laying waste and destroying, as has been already related; but formidable fleets were sent to attack the whole extent of sea coast. In 1697, the historian informs us, “an invasion was every day expected for several weeks together; and news was brought to Boston, that a formidable French fleet had been seen upon the coast.”

The reality of a plan to destroy English colonies, and particularly New England, is stated by Charlevoix, in the account given him, of the above mentioned expedition. A powerful army from Canada, was to meet a fleet from France early in the season at Penobscot; and, “as soon as the junction was made, and the troops embarked, the fleet, without loss of time, was to go to Boston, and that town being taken, it was to range the coast, — destroying settlements as far into the country as they could.”6 — This projected expedition, had it been executed, might have been fatal to our country; but, by reason of contrary winds, the fleet did not arrive in season, and the plan was frustrated.

Another projected invasion is within the recollection of some of us. The elderly people have not yet forgotten their fears and apprehensions, when the strong force under the Duke D’Anville, was expected in this harbour; nor have they lost a remembrance of the joy they felt, when that fleet was scattered and many ships were destroyed by the winds and the waves.

Such of us, as are advanced in life, remember our fears during a course of years, while the French surrounded us, except on the Atlantic; and on that side also, they were threatening to invade us : — when our armies were defeated, which were sent to protect the frontiers; when the young Washington found it necessary to capitulate.7 Washington, who about fourteen months after, by skill and bravery, saved the broken remains of an army, late commanded by General Braddock; and who, by the providence of God, was preserved to be the Saviour of his Country.

But I will weary you no longer with the sad detail of wars, in which the Fathers of New England suffered from the French and the savages of the wilderness. In short, they had but little rest from the time of Philip’s war, until Quebec was taken by the immortal Wolfe, and the whole country was ceded to Great Britain in 1763.

Having talked as long perhaps as may be proper, of the mercy which God was pleased to show to the Fathers of our Country; and of the protection granted to them and to their children in seasons of weakness and danger, and when exposed to the savages of the wilderness, and to other powerful enemies; we are prepared to talk of like protection and favours granted to the American people in later times : — of their dangers and sufferings during a severe conflict for the security of their most important interests; a conflict which terminated in the establishment of a new state of things in this quarter of the world, — a new empire, which, in process of time will probably be equal in extent, in power, and in wealth, to any nation in the world. But should we talk of the revolutionary war, — of the causes which produced it, — of its progress and important events; and of the honourable terms of peace, obtained by the plenipotentiaries of the United States at Paris in 1783, our discourse would not only be unreasonably long, but we should have no time left, to talk of the late war, in which our country has been engaged, — of the peace which is again restored to us; and to indulge in pleasing anticipation, the comforts and blessings which, not only the American people, but, we hope, the world may enjoy, in a state of tranquility.

As the events of that war which procured the independence and the sovereignty of the United States of America are within the recollection of such of you have passed a little over the middle of life; and the history of it is in almost every family, I shall omit any farther conversation with respect to it, and go on to talk of the late war, and of the peace, which we on this day celebrate.

It would certainly be attended with very little pleasure and probably with very little profit now that the war is ended, to talk much about the reason assigned for it when it was proclaimed, or of the important objects which were to be secured by it. We remember the many unpleasant feelings occasioned by the contentions of men of different opinions, concerning the origin, and the manner in which the late war was conducted. We hope such uncomfortable feelings may now wholly subside, and that no restless people among us, may hereafter, by rash speeches, or inflammatory publications, again revive them. Although we have not yet learned that the objects for which the late war was declared, have been obtained or secured, we rejoice that the conflict is at an end. We do sincerely rejoice at the return of peace. We will therefore talk of the wondrous goodness of God, both in conducting the American people through the war, and in giving the rulers of the late contending nations pacifick dispositions.

Should the peace continue, which is now established among the Christian nations of the earth, opportunities will offer for the execution of the most benevolent purposes of the human heart. A state of peace is favourable to the propagation of the gospel, — to the advancement of science and all the useful arts, — to commerce, — to every thing which gives true dignity to man, and tends to qualify him for the rank which he is designed to hold in creation.

Divine Providence seems to have been preparing the way for the spread of truth, and the farther establishment of the kingdom of Christ. That Being who superintends the changes and revolutions which take place among the nations of the world, will always bring good out of apparent evil; and therefore while we mourn over the late sufferings of a great portion of our fellow men on the continent of Europe, we find consolation in the belief, that good will result from those sufferings.

In the dark ages of ignorance and superstition, when the religion of Jesus was awfully corrupted, and civil liberty was poorly understood, combinations were formed by the rulers of the church, and by the princes of this world, to support each other in the most shameful acts of tyranny and oppression. Although much had been done at the time of the reformation, and at succeeding periods, to lessen the power, which kings and priests had usurped over the worldly estates, and over the spiritual concerns of the people, much remained to be done. Bigotry and superstition may still bluster and threaten, but they can no longer hold the minds of a great part of mankind in bondage; they can no longer prevent free inquiry such is the power of truth, that it will prevail. “Many shall run to and fro; and knowledge shall increase.”

At no period since the great opposition to popery by Luther, and the reformers who followed after him, have Christians of all denominations been so well united, as they are at the present time in laudable endeavours to extent the knowledge of salvation. Within a few years, societies have been formed in England and in various parts of Europe, consisting of members of great respectability having for their object “the distribution of the Bible.” Societies for the same purpose have been recently formed in the principal cities and towns in North America. The wonderful union of Christians of all denominations, and of all orders of people, from the highest to the lowest, in this noble work of charity, affords the highest encouragement to the friends of Zion, and is, we trust, a presage of that happy condition of the world, which we are taught to expect, when “All shall know the Lord.”

As the most benevolent purposes of God are brought to pass, by means adapted to the ends which are to be accomplished, wise observers may perceive a fitness in the means, and in working of providence, to accomplish such purposes. If there is to be a time, when “the earth shall be full of the knowledge of the Lord,” we shall have reason to think, God is preparing the way for a condition so desirable, when kings and mighty men, — when high and low, — when Christians of every creed, and of every mode of worship, unite their labours and good wishes to extend the only effectual means of religious knowledge to all countries, and to all regions.

There are other circumstances in the present state of the civilized nations of the earth, favourable to the propagation of truth, which have not heretofore existed to the extent in which they now exist. Civil liberty, and the rights of conscience, are better understood, and will no doubt, be more respected, than heretofore. Well informed Christians have more moderation, more candor, more charity for one another, although still differing in opinions, and in modes of worship, than have been exercised at any former period, since the church and the world were united, for the support of each other.

Under circumstances such as we have now mentioned, and on which we might enlarge with great pleasure would the time admit, under such circumstances, aided by peace, and by the intercourse now opened, and more widely opening among the different nations of the world, we indulge a pleasing hope, that the gospel shall be carried to every part of the globe; that the light of the sun; and “people of all kindreds and tongues, and nations, shall walk in the light.”

The peace which we this day celebrate has opened the American ports, not only to the nation with which we have been at war, but to a great part of the nations of the world. The commerce of our country, which had been languishing until there was scarcely an appearance of life, hath sprung up at the voice of peace, and is beginning to assume its wonted cheerful appearance. We again hear the noise of the axe and the hammer. “Zebulon is beginning to rejoice in his going out, and Issachar in his tents.”

Peace is highly favourable to science, to the useful arts, to agriculture, and to all the social connexions of life. In a time of war the mind is disturbed; the thoughts are divided; it is impossible to give that application to study, which is necessary to the acquirement of extensive knowledge.

In a time of war, multitudes are called from their usual occupations, and from domestic enjoyments, exposed to privations, to dangers, and to death. Ware is an evil; a judgment which God inflicts on the sinful nations of the earth. During the late war, our nation has suffered a variety of evils. Many lives have been lost. Vast property has been taken and carried away, or destroyed on the seas : vast sums have been expended, and vast debt hath been contracted. Towns have been invaded, — villages have been burnt, — the capitol has been laid in ashes. We are glad to set down in peace, under circumstances, no doubt, less eligible, than the friends and supporters of the war expected. We have reason to be thankful that our sufferings have not been greater : — that the conflict was no longer continued.

Truly we may say, “If it had not been that the Lord was on our side,” when a powerful enemy invaded our coasts, — “if it had not been that the Lord was on our side,” when men of renown, of uncommon strength and skilled in war, and men accustomed to conquer by sea and by land, — “if it had not been that the Lord was on our side,” when such men with powerful fleets and powerful armies came against us, — “then they had swallowed us up quick, when their wrath was kindled against us! Then the waters had overwhelmed us, the stream had gone over our soul. Then the proud waters had gone over our soul. Blessed be the Lord who hath not given us as a prey to their teeth. Our soul is escaped as a bird out of the snare of the fowlers: the snare is broke and we are escaped.”

In a review of the wondrous works of God, as they relate to the fathers of our country, and to their children, and their children’s children, to the fifth and the sixth generation, we see many things which call for our gratitude, and many things which call for sober reflection and humiliation. Towards the American people, while they were under the government of Great Britain, and since they have been free and independent states, the dispensations of Providence have been merciful, and they have been afflictive. As the children of Israel were marvelously protected when they went out of the land of Egypt, but were afterwards corrected for their faults, and grievously afflicted; so were our fathers protected; but the first generation had not passed away, before the heathen brake in upon them, and they were afflicted.

The history of our country, is a history of its prosperities, and of its adversities; fo its happiness in times of peace, and of its sufferings in seasons of war.

On this day, we are invited by the supreme Magistrate of the United States, to assemble in our place of worship, and to unite our hearts and our voices, “in a free will offering,” of thanksgiving and praise to our Heavenly Benefactor for his great goodness manifested in restoring to us “the blessings of peace.” “No people,” the president observes in his proclamation, “No people ought to feel greater obligations to celebrate the goodness of the Great Disposer of all events, and of the destiny of nations, than the people of the United States. His kind Providence originally conducted them to one of the best portions of the dwelling place allowed for the great family of the human race. He protected and cherished them, under all the difficulties and trials to which they were exposed in their early days. Under his fostering care, their habits, their sentiments, and their pursuits, prepared them for a transition, in due time, to a state of independence and self-government. In the arduous struggle by which it was attained they were distinguished by multiplied tokens of his benign interposition. And to the same Divine Author of every good and perfect gift, we are indebted for all the privileges and advantages, religious as well as civil, which are so richly enjoyed in this favoured land.”

While making our offering of thanksgiving and praise to Almighty God, for the peace which he hath been pleased to ordain for us, many circumstances occur to our minds, which render the event which we now celebrate, peculiarly grateful, and which call for the exercise of our best affections.

Had the war continued another season, it would have become more fierce and cruel. A disposition to plunder, and retaliate injuries, on both sides, had been for some time increasing, and we have reason to fear, that a continuance of the war would not only have afforded opportunities, but excitements to still more shocking deeds’ in which, not only men in arms, but un offending citizens in the peaceful walks of life, would have been subjected to inexpressible sufferings.

Had the war continued another season, the forces of the enemy in the Canada’s, on the lakes, and on our sea coasts, would have been greatly increased: much greater exertions therefore would have been required on the part of the United States. What ways and means should have been devised for the support of such armies as must have been called out to defend an extensive sea coast, and an equally extensive frontier, those public men may, perhaps be able to say, who had the management of the finances during the two last seasons.

Had the war continued, multitudes must have been called from the fields of husbandry, from manufacturing establishments, and other useful and necessary employments, and hurried away to exposed parts of the country, to suffer in camps and to die in battle.

Had the war continued, the spring would have opened upon us with gloomy forebodings. In the winter season, the ice and the snow were our best defense. With the returning sun, our fears would have increased our apprehensions. But with the peace, which God in mercy hath granted us, the whole scene of things is changed. We hail each lengthening day with the smile of cheerfulness. We behold the vernal skies, and we receive the vernal showers, with unmingled pleasure. “We will now give thanks unto the Lord; we will call upon his name; we will make known his deeds among the people; we will sing unto him; we will sing psalms unto him; we will talk of all his wondrous works.”

That our offering of thanksgiving and praise, may be acceptable to God, let it be accompanied with kind affection towards all our fellow citizens, and towards the people whom we lately considered as our enemies.

“Whatever differences of opinion may have existed,” with respect to the origin of the late war, or any of the measures in which it hath been conducted, all now rejoice, in that the conflict is at an end. “All good citizens will unite in providing still farther for our external security, as well as internal prosperity and happiness, by fidelity to the union, by reverence for the laws, by discountenancing all local and other prejudices, and by promoting everywhere the concord and brotherly affection becoming members of one great political family.”8

As we are again at peace with the government and people of Great Britain, let us suppress, as much as possible, the feelings of resentment which are apt to rise from a recollection of sufferings and injuries,. The brave are always generous: they are the first to forgive and forget. If we have suffered, our enemy too has suffered. Let the balm of peace now heal every wound. If the scar remain, lest us be careful, lest by fretting, the blood be made again to appear.

As the brave are always generous, the brave will never exult, when a powerful enemy has been beaten. We are to remember, the race is not always swift, nor is the battle always to the strong. While the American arms have, without question, secured immortal fame, it must be confessed that little else has been secured, for the United States, by a vast expense in blood and treasure.9

It is now devoutly to be wished, that all ill will, and all party spirit may be put away. Why should party spirit and party feelings continue, when, it is presumed, there can now be no foreign influence to support a party? Whatever there may have been in times past, at present there can be no particular attachments to foreign nations, to influence American citizens. If any internal contentions be kept alive, they must be such as are found to a certain degree, in all elective governments : a contention for power, for places, — for “the loaves and fishes.” A man surely can have very little modesty, who seeks for honours and preferments which the public is not willing to give him. In an uncorrupted state of society, men will not be seen making interest for places of honour and profit. Men well known to be qualified men of approved integrity and uprightness, will be sought for, and solicited, to accept offices of high responsibility. God grant that we may live to see a return of something like that golden age of purity and simplicity, which our country once enjoyed!

My beloved people, although I have now talked with you a long time, I feel unwilling to close my discourse, without offering my very particular and most affectionate congratulations on the present joyous occasion. On a like occasion I once addressed some of you. The peace of 1783, after a sever contest for independence and sovereignty, was a glorious peace. It is to the highest degree improbable, that I shall again, at any future time, address you on a similar occasion: or on any political subject. Four seasons of distressing warfare are within my recollection. The war of 1745, the war of 1755, the war of 1775, and the late war declared on the part of the United States June 18, 1812. I have seen important changes and revolutions in my own country, and among the nations of the world I have seen one generation pass away, and another generation come forward. I have seen a nation rise up in this quarter of the world, powerful in men and in arms, and taking rank among the other nations of the earth. Such changes I have seen; but my days of vision on earth are drawing to an end. My country, now at peace, I hope will continue in peace long. Very long, after it shall please God to take me to that “better country,” where wars are unknown.

My heart’s desire and prayer has been for the prosperity and peace of our Jerusalem. May those always prosper who seek her peace!

It was for the love which I had for my country; — the country in which I was born —in which my friends live — in which the people live with whom I am connected by ties which have made, and which still make my abode pleasant to me; for the love which I had, and which I still have for this country, I have discoursed to you several times on its rights and its liberties — on its dangers and its sufferings. I have rejoiced with my country when in prosperity; and mourned when in adversity. As the Comforts which we enjoy in the peace and prosperity of our country, are as truly the gifts of God, as the comforts which we hope to enjoy a future life, we should be unjust to ourselves, and ungrateful to our heavenly Benefactor, did we not endeavour to defend and secure them, when men of violence attempt to take them away from us: I therefore thought, and still think, it was my duty to give warning when the important interests of my country appeared to be in danger. When those important interests were actually invaded, I thought, and still think, it was my duty to say and to do what I was able, to support them. In this I thought, and still think, I had great and good examples, in the prophets and apostles. Jesus Christ also, with the perfect feelings of a perfect man, loved his country, and wept over its capital, when he knew its destruction was approaching. In my youth I was taught to regard civil and religious liberty, with a kind of reverential respect. That sort of devotion I strengthened afterwards, by reading and meditation; nor do I perceive that my attachment to those objects of my early affection, has in any measure abated now I am old.

For the full enjoyment of civil and religious liberty, together with the inestimable blessings connected with them, the fathers of New England exchanged the wealth and the accommodations of their native country, for the poverty and the sufferings of a wilderness. I pray God, the offspring of those excellent men, may never suffer their birth-rights to be taken from them.

I rejoice that my country is again at peace with the government and people of Great Britain; a people of high spirits and somewhat vindictive; but a people possessing many strong virtues. A people, who, with all their faults, have done more to encourage useful institution and to send the true knowledge of salvation to the dark parts of the earth than any other nation, and I may say, than all the other nations in the world. It would be unjust, and base, and wicked, to impute to the present inhabitants of Great Britain, the bigotry and the persecuting spirit of their great grandfathers.

I rejoice that the world is again at peace. The temple of Janus is again shut. The earth is at rest. God grant that henceforth the only contest may be, who shall do most to enlighten the ignorant; who shall do most to reform the guilty; and to use the words of the great Washington, the beloved father of our country, with whose words I conclude, — who shall do most “to make our neighbours and fellow men as happy, as their frail conditions and perishing natures will permit them to be.”10

NOTES

Note A. Some persons who heard the discourse expressed their surprise that this Indian warrior should be known by an English name. We have an explanation in Hutchinson’s History of Massachusetts. Vol. 1st. p276.After the Indians became acquainted with the Europeans who had settled among them, “they were fond of having names given to them.” In 1662 when Massasoiet’s two sons were at Plymouth the governor gave them their English names.” To Wamsutta the eldest son of Massasoiet, governor Prince gave the English name Alexander: to the second son, whose Indian name was Metacom, the governor gave the English name, Philip.

In Neal’s History of New England, Philip is said to be “grandson of old Massasoiet.” “He was a bold and daring prince, having all the pride, fierceness, and cruelty of a savage.” Neal’s Hist. Vol. II. p. 23. The wonderful destruction of the Indians by wars and sickness, before the arrival of the fathers of New England, is related by Mr. Gookin. See Historical Collections, Vol 1st, p. 148. Morton’s New England’s Memorial. P 37, 38. Prince’s Chronology, p.69.

Note B. The quotation to which this note has relation is made from the president’s excellent Answer to the “Tribute of Respect,” or “Congratulatory Address of the Republican member of both branches of the Legislature of Massachusetts, and other citizens.” Which “was voted to be communicated to the President, on the restoration of peace.” Feb. 23, 1815.

Note C. Hon. William Gaston, member of congress from North Carolina, in his circular letter dated at Washington, March 1, 1815, writes thus : “Some time must yet elapse before we ascertain with certainty the addition the war has made to our publick debt. Claims are even now brought before congress which had their origin in the war of the revolution; and this which has just past, short as was its continuance has given rise to many more than our revolutionary struggle.”

Hon. Cyrus King, member of congress from Massachusetts, in a speech delivered Feb. 27, 1815, states the loss of men, “brave Americans,” 30,000. And the amount of treasures sacrificed, “150,000,000.”

Note D. As the words of Washington are words of wisdom, the reader will be gratified by having a few more from the letter quoted at the end of the discourse.

—“I observe with singular satisfaction, the cases in which your benevolent institution,” (the Massachusetts Humane Society,) “has been instrumental in recalling some of our fellow creatures, as it were, from beyond the gates of eternity, and has given occasion for the hearts of parents and friends to leap for joy. The provisions made for shipwrecked mariners is also highly estimable in the view of every philanthropic mind, and greatly consolatory to that suffering part of the community. These things will draw upon you the blessings of those who were ready to perish. These works of charity and goodwill towards men, reflect, in my estimation, great lustre upon the authors, and presage an era of still farther improvements. How pitiful, in the eye of reason and religion, is that false ambition which desolates the world with fire and sword for the purposes of conquest and fame; when compared to the milder virtues of making our neighbours and our fellow men, as happy, as their frail conditions and perishable natures permit them to be!”

Now the writer of the above almost divine sentences is no more among the living, may we exclaim, “How pitiful in the eye of reason and religion” are the heroes of antiquity, — the Alexanders and the Caesars, the Pompies, the Charleses, the Edwards, the Henries, and all who have “desolated the world with fire and sword for the purposes of conquest and fame, when compared” with Washington, who fought only for the liberties and the safety of his country’ and having accomplished the great objects for which he drew his sword, returned to private life!

Endnotes

1 Holmes’s Annals, I:207.

Samoset, it may be supposed, obtained some knowledge of the English language from Capt. John Smith and others, who visited this country and began a commerce with the Indians in the years 1614 and 1615.

2 Hutchinson’s Hist. I:176 and 283.

3 See Note A.

4 Holmes’s Annals I:472.

5 As far as the river Kennebeck. Hutchinson’s History of Massachusetts, II:111.

6 Hutchinson’s Hist. V:ii:102.

7 Holmes’s Annuals, V:ii:199.

8 See Note B.

9 See Note C.

10 A letter, dated at Mount Vernon June 22, 1788. See Note D.

John Lathrop (1740-1816) Biography:

John Lathrop (1740-1816) Biography:

On March 4, 1789, the

On March 4, 1789, the

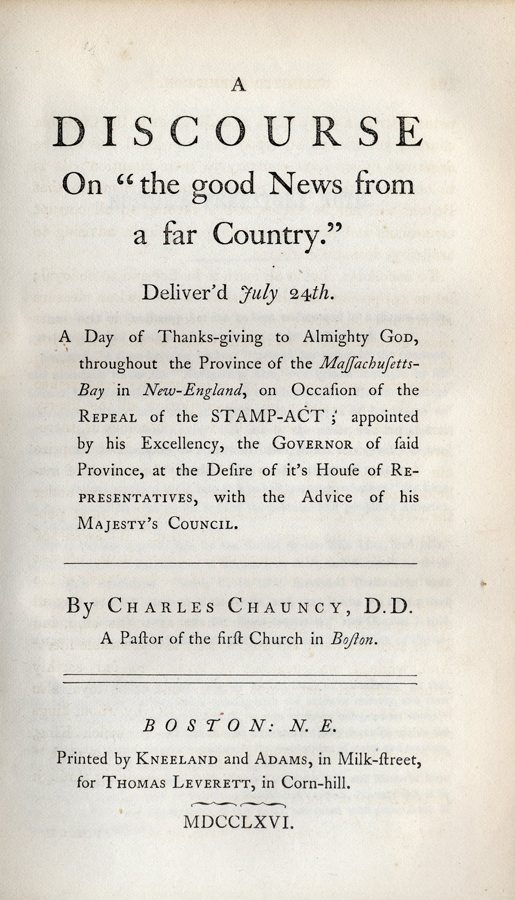

On July 24, 1766

On July 24, 1766  In 1815, John Adams

In 1815, John Adams  During the early days of the War for Independence—while the gun smoke still covered the fields at Lexington and Concord, and the cannons still echoed at Bunker Hill—America faced innumerable difficulties and a host of hard decisions. Unsurprisingly, the choice of a national flag remained unanswered for many months due to more pressing issues such as arranging a defense and forming the government.

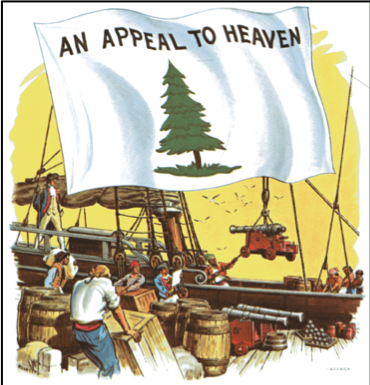

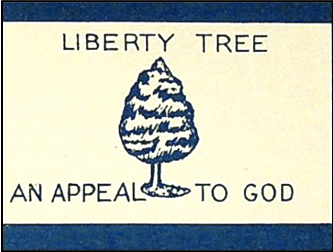

During the early days of the War for Independence—while the gun smoke still covered the fields at Lexington and Concord, and the cannons still echoed at Bunker Hill—America faced innumerable difficulties and a host of hard decisions. Unsurprisingly, the choice of a national flag remained unanswered for many months due to more pressing issues such as arranging a defense and forming the government. In fact, prior to the Declaration of Independence but after the opening of hostilities, the Pinetree Flag was one of the most popular flags for American troops. Indeed, “there are recorded in the history of those days many instances of the use of the pine-tree flag between October, 1775, and July, 1776.”

In fact, prior to the Declaration of Independence but after the opening of hostilities, the Pinetree Flag was one of the most popular flags for American troops. Indeed, “there are recorded in the history of those days many instances of the use of the pine-tree flag between October, 1775, and July, 1776.” As the skirmishes unfolded into all out warfare between the colonists and England, the Pinetree Flag with its prayer to God became synonymous with the American struggle for liberty. An early map of Boston reflected this by showing a side image of a British redcoat trying to rip this flag out of the hands of a colonist (see image on right).

As the skirmishes unfolded into all out warfare between the colonists and England, the Pinetree Flag with its prayer to God became synonymous with the American struggle for liberty. An early map of Boston reflected this by showing a side image of a British redcoat trying to rip this flag out of the hands of a colonist (see image on right). The fact that Locke writes extensively concerning the right to a just revolution as an appeal to Heaven becomes massively important to the American colonists as England begins to strip away their rights. The influence of his Second Treatise of Government (which contains his explanation of an appeal to Heaven) on early America is well documented. During the 1760s and 1770s, the Founding Fathers quoted Locke more than any other political author, amounting to a total of 11% and 7% respectively of all total citations during those formative decades.

The fact that Locke writes extensively concerning the right to a just revolution as an appeal to Heaven becomes massively important to the American colonists as England begins to strip away their rights. The influence of his Second Treatise of Government (which contains his explanation of an appeal to Heaven) on early America is well documented. During the 1760s and 1770s, the Founding Fathers quoted Locke more than any other political author, amounting to a total of 11% and 7% respectively of all total citations during those formative decades. Furthermore, the Pinetree Flag was far from being the only national symbol recognizing America’s reliance on the protection and Providence of God. During the War for Independence other mottos and rallying cries included similar sentiments. For example, the flag pictured on the right bore the phrase “Resistance to Tyrants is Obedience to God,” which came from an earlier 1750 sermon by the influential Rev. Jonathan Mayhew.

Furthermore, the Pinetree Flag was far from being the only national symbol recognizing America’s reliance on the protection and Providence of God. During the War for Independence other mottos and rallying cries included similar sentiments. For example, the flag pictured on the right bore the phrase “Resistance to Tyrants is Obedience to God,” which came from an earlier 1750 sermon by the influential Rev. Jonathan Mayhew.

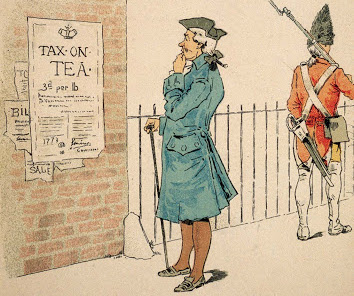

As a brief background, the British Parliament had been passing laws taxing American colonists for years without allowing for any recourse through representation in Parliament. (Although the Colonists had elected representatives in local government, they had no elected leaders to represent them in England.) This principle of arbitrary power exerted by the government was clearly illustrated by a tax on imported tea despite colonial resistance.

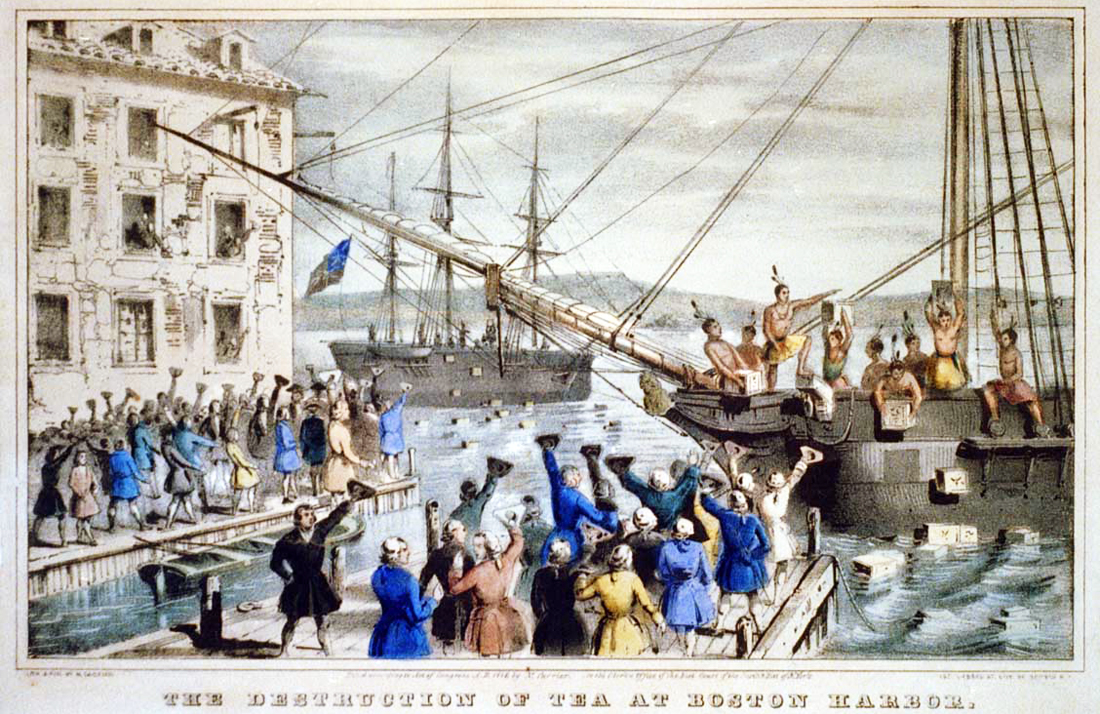

As a brief background, the British Parliament had been passing laws taxing American colonists for years without allowing for any recourse through representation in Parliament. (Although the Colonists had elected representatives in local government, they had no elected leaders to represent them in England.) This principle of arbitrary power exerted by the government was clearly illustrated by a tax on imported tea despite colonial resistance. With time running out and all other options exhausted, nearly 7,000 Bostonians gathered at the Old South Meeting House and learned from ship’s owner, Joseph Rotch, that his request to sail back to England had been rejected and that if the tea was not unloaded that night it was subject to confiscation by the English navy (who undoubtedly would land the tea and tax the colonists).

With time running out and all other options exhausted, nearly 7,000 Bostonians gathered at the Old South Meeting House and learned from ship’s owner, Joseph Rotch, that his request to sail back to England had been rejected and that if the tea was not unloaded that night it was subject to confiscation by the English navy (who undoubtedly would land the tea and tax the colonists).