The Constitution originally organized the judiciary in a manner providing for appointed judges, serving for the duration of “good behavior” (Art. III, Sec. 1, Par. 1). That appointed system performed admirably while a common value system was embraced by the nation. (For example, even though Declaration signers Benjamin Franklin and the Rev. Dr. John Witherspoon held divergent religious views, there were few differences in their governmental philosophy or approach to common cultural values.) The success of the appointed system was further enhanced by the fact that the judiciary did not view itself as a super-legislature; policy-making was anathema to that branch, and it was extremely unusual for the judiciary to strike down any act of the legislature. As a supreme court explained in 1838:

The Court, therefore, from its respect for the Legislature – the immediate representation of that sovereign power [the people] whose will created and can at pleasure change the Constitution itself – will ever strive to sustain and not annul its [the Legislature’s] expressed determination. . . . [A]nd whenever the people become dissatisfied with its operation, they have only to will its abrogation or modification and let their voice be heard through the legitimate channel, and it will be done. But until they wish it, let no branch of the government – and least of all the Judiciary – undertake to interfere with it. [1] (emphasis added)

Most judges today no longer embrace this view. Consequently, State policies on issues from education to criminal justice, from religious expressions to moral legislation, from financing to health now stem more frequently from judicial decisions than legislative acts. In fact, in recent years, even the federal court has described itself as “a super board of education for every school district in the nation,” [2] “a national theology board,” [3] and amateur psychologists on a “psycho-journey.” [4] Judges now endorse the declaration of Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo that:

I take judge-made law as one of the existing realities of life. [5]

As a result, there are now two constitutions for most states: the ratified constitution with its explicitly written language, and the unratified living constitution that evolves from decision to decision (or, as explained by Supreme Court Chief-Justice Charles Evans Hughes: “We are under a Constitution – but the Constitution is what the judges say it is.” [6]) And unfortunately, just as there are now two constitutions, there are also now two public policy-making bodies: the elected legislature and the appointed judiciary.

With two such radically different constitutions and distinctively different public policy bodies, citizens should have the choice of the constitution and public policies under which they must live. Otherwise (as Samuel Adams wisely observed):

[I]f the public are bound to yield obedience to [policies] to which they cannot give their approbation, they are slaves to those who make such laws and enforce them. [7]

While defenders of an activist judiciary often assert that an independent appointed judiciary does not hold political views, such claims are specious and are not confirmed by contemporary experience. As Thomas Jefferson long ago observed, it is naive to assume that judges do not have political views on most issues before them:

Our judges are as honest as other men and not more so. They have, with others, the same passions for party, for power, and the privilege of their corps. . . . and their power the more dangerous as they are in office for life and

not responsible – as the other functionaries are – to the elective control.[8]

Recent months have provided numerous examples of the people expressing a clear will on an issue and the judiciary then abrogating that will.

Most recently, a state judge struck down California’s Prop 22 (enacted in 2000) declaring that marriage is only between a man and a woman. That judge unilaterally took the definition of marriage out of the hands of the people and substituted his own – as did judges in Hawaii, Vermont, and Massachusetts.

In Kansas, the legislature recently passed a death penalty statute at the behest of the people but the state supreme court struck it down, chiding both the legislature and the people. And despite the constitutional requirement that all spending originate and reside solely in the legislature, the court ordered additional spending on education lest the court take control of educational funding.

And in Nevada, even though the state constitution requires a 2/3rds majority of the legislature to increase taxes, its supreme court ordered that clause to be ignored and instead directed a tax increase to boost spending on education. Unbelievably, the state court ruled that part of the state constitution was unconstitutional!

Then in New Jersey, a 2002 candidate for U. S. Senate fell far behind in the polls; with 35 days left before the election, that candidate withdrew his name from the ballot. His party sought to place a new name on the ballot but State law stipulated that a candidate’s name could be replaced only if the “vacancy shall occur not later than the 51st day before the general election.” Despite the clear wording of the law, the appointed court ordered a new name to be placed on the ballot. That candidate surged in the polls and because the court ignored the law in order to advance a political agenda and gives one party two choices rather than one, his party won a U. S. Senate seat they were destined to lose.

And recall the Florida Supreme Court in the 2000 presidential election? State law explicitly declared that all election vote tallies were to be submitted to the Secretary of State’s office by 5 PM on the 7th day following the election, and that results turned in past that time were to be ignored; yet those judges ruled that 5 PM on the 7th day really meant 5 PM on the 19th day, and that the word “ignored” really meant just the opposite – that the Secretary of State must accept all results, even those that did not comply with the law.

There are many other similar examples demonstrating that in States with an appointed judiciary, judges are quite comfortable in exerting political influence rather than simply upholding and applying State laws.

Given the growing proclivities now evident throughout appointed judiciaries, it is time for States with appointed judges to move toward elected judges – as Texas, New York, Louisiana, Pennsylvania, Alabama and more than half the States already have. And any argument that what occurred in New Jersey, California, Nevada, et. al, will not occur in other States ignores the fact that the current trend is not the result of demographics; rather, it is the result of what has been taught in law schools in recent decades. Consequently, the instances of judges acting as super-legislators will continue to increase.

The election of judges can now help preserve America’s two fundamental government principles: government by “the consent of the governed,” as authorized and approved by “We the people.” Additionally, there are three fundamental historic principles that further buttress the current efforts to move toward elected judges.

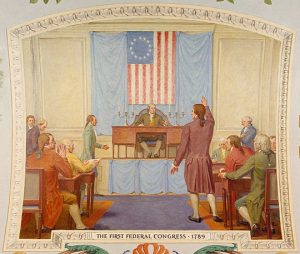

Principle #1: Under American Government as Originally Established, the People are Ultimately in Charge of All Three Branches

The same Framers who established the three separate branches also established the principle that none of the branches was to be beyond the reach of the people. For example, the early State constitutions written by those who also framed the national government contain declarations such as:

All power residing originally in the people and being derived from them, the several magistrates and officers of government vested with authority – whether legislative, executive, or judicial – are their substitutes and agents and are at all times accountable to them [the people]. (emphasis added) [9]

Thomas Jefferson reiterated this important principle on numerous occasions. For example, when setting forth to the French the most important aspects of American government, he explained:

We think, in America, that it is necessary to introduce the people into every department of government. . . . Were I called upon to decide whether the people had best be omitted in the legislative or judiciary department, I would say it is better to leave them out of the legislative. The execution of the laws is more important than the making them. [10]

Since judges often have the final word, it is important that the people have a voice in that branch. In fact, if the “execution of the laws” by the judiciary regularly counters the will of the legislature (and thus uncorrectable by the people), then citizens will lose respect for government. As Luther Martin accurately warned at the Constitutional Convention:

It is necessary that the supreme judiciary should have the confidence of the people. This will soon be lost if they are employed in the task of remonstrating against [opposing and striking down] popular measures of the legislature. [11]

Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story (a “Father of American Jurisprudence,” appointed to the Court by James Madison) further warned that an unaccountable judiciary would create a general dislike and distrust of the judiciary by the citizenry:

[An] accumulation of power in the judicial department would not only furnish pretexts for [complaint] against it but might create a general dread of its influence. [12]

It is an established principle of American government that the judiciary is to be accountable to the people, and judicial elections safeguard this principle.

Principle #2: The Independence of the Judiciary is Not Violated by the Election of Judges

Today, the term “independent” as applied to the judiciary has largely become a euphemism for “unaccountable”; and not surprisingly, many judges, when given increased levels of protection from the public, feel freer to advance personal agendas. Thomas Jefferson wisely observed that no official was to be so “independent” as to be beyond the reach of the people:

It should be remembered as an axiom of eternal truth in politics that whatever power in any government is independent is absolute also; in theory only, at first, while the spirit of the people is up, but in practice as fast as that relaxes. Independence can be trusted nowhere but with the people in mass.[13]

Only the people – and not the judiciary – can be safely trusted with complete independence. The term “independent” as currently used in relation to the judiciary is incorrectly applied – as pointed out by William Giles (1762-1830), a member of the first federal Congress:

With respect to the word “independent” as applicable to the Judiciary, it is not correct nor justified by the Constitution. This term is borrowed from Great Britain – and by some incorrect apprehension of its meaning there – . . . is applied here. [14]

In fact, when some clamored that the judiciary should be “independent,” judge and U. S. Rep. Joseph Nicholson (1770-1817) forcefully reminded them:

By what authority are the judges to be raised above the law and above the Constitution? Where is the charter which places the sovereignty of this country in their hands? Give them the powers and the independence now contended for and they will require nothing more, for your government becomes a despotism and they become your rulers. They are to decide upon the lives, the liberties, and the property of your citizens; they have an absolute veto upon your laws by declaring them null and void at pleasure; they are to introduce at will the laws of a foreign country, differing essentially with us upon the great principles of government; and after being clothed with this arbitrary power, they are beyond the control of the nation, as they are not to be affected by any laws which the people by their representatives can pass. If all this be true – if this doctrine be established in the extent which is now contended for – the Constitution is not worth the time we are now spending on it. It is, as its enemies have called it, mere parchment. For these judges, thus rendered omnipotent, may overleap the Constitution and trample on your laws; they may laugh the legislature to scorn and set the nation at defiance. [15]

The notion of independence as now applied to the judiciary was repugnant to the Framers of American government – as confirmed by Constitution signer John Dickinson:

What innumerable acts of injustice may be committed, and how fatally may the principles of liberty be sapped, by a succession of judges utterly independent of the people? [16]

In short, the modern notions of judicial independence are glaringly absent from the constitutional organization of the branches. No branch is to be unaccountable to the people, and judicial elections ensure accountability.

Principle #3: The Judiciary is to be Accountable to the People, and Election of Judges Currently Accomplishes what Impeachment Did During the First Century of American Government

Originally, every appointed judge was made accountable to the people through impeachment; and literally dozens of impeachment proceedings were conducted during the first century of the nation. [17]

Judges were removed from the bench for everything from cursing in the courtroom to rudeness to witnesses, from drunkenness in private life to any other conduct or behavior that was unacceptable to the public at large. (Only in the past half century has the level for an impeachable offense been erroneously redefined to be the commission of a major felony; with this incorrect standard, the people’s ability to hold judges accountable has been greatly diminished.) The election of judges will now ensure a level of judicial accountability that impeachments once provided. It is instructive to examine the original grounds for removal of judges through impeachment and to note that these would be the very same grounds used today for removal of judges through elections.

What were the offenses that allowed for the removal of judges during America’s early years? According to Justice Joseph Story, those offenses included “political offenses growing out of personal misconduct, or gross neglect, or usurpation, or habitual disregard of the public interests.” [18]

And Alexander Hamilton explained that judges could be removed for “the abuse or violation of some public trust. . . . [or for] injuries done immediately to the society itself.” [19]

Constitutional Convention delegate Elbridge Gerry considered “mal-administration”[20] as grounds for a judge’s removal, and early constitutional scholar William Rawle also included “the inordinate extension of power, the influence of party and of prejudice” [21] as well as attempts to “infringe the rights of the people.” [22]

Very simply, judges could be removed whenever they disregarded public interests, affronted the will of the people, or introduced arbitrary power by seizing the role of policy-maker.

But would not a system of judicial elections be unfair to judges, or become a deterrent to good judges serving? Certainly not. As explained by Justice Story:

If he [a judge] should choose to accept office, he would voluntarily incur all the additional responsibility growing out of it. If [removed] for his conduct while in office, he could not justly complain since he was placed in that predicament by his own choice; and in accepting office he submitted to all the consequences. [23]

In fact, rather than keeping good judges from serving, the election of judges would do just the opposite: it would will help remove the most incompetent from office and – in the words of John Randolph Tucker (a constitutional law professor and early president of the American Bar Association) – it would “protect the government from the present or future incumbency of a man whose conduct has proved him unworthy to fill it.” [24]

Very simply, judicial elections guard the principle of judicial accountability set forth by Justice James Iredell (placed on the U. S. Supreme Court by George Washington), who asserted:

Every man ought to be amenable for his conduct. . . . It will be not only the means of punishing misconduct but it will prevent misconduct. A man in public office who knows that there is no tribunal to punish him may be ready to deviate from his duty; but if he knows there is a tribunal for that purpose, although he may be a man of no principle, the very terror of punishment will perhaps deter him. [25]

Election of judges is nothing more than a tool to protect the rights of the people collectively. It once again makes the judiciary an accountable branch (as was originally intended), holding individual judges responsible for their decisions and thus preventing their usurping, misusing, or abusing power.

Summary

In this day of rampant judicial agendas, proposals that judges should be protected from citizens are untenable. History is too instructive on the necessity of direct judicial accountability for its lessons to be ignored today; and while judicial accountability through the use of impeachment on the federal level appears to be a thing of the past, judicial accountability through the direct election of State judges should not be. Elected judges should know that if they make agenda-driven decisions, they not only may face a plethora of opponents in their next race who will remind voters of their demonstrated contempt for State law but they will also have to face the voters themselves. Election of judges restores the original vision that:

All power residing originally in the people and being derived from them, the several magistrates and officers of government vested with authority – whether legislative, executive, or judicial – are their substitutes and agents and are at all times accountable to them [the people]. [26]

Endnotes

[1]Commonwealth v. Abner Kneeland, 37 Mass. (20 Pick) 206, 227, 232 (Sup. Ct. Mass. 1838).

[2]McCollum v. Board of Education; 333 U. S. 203, 237 (1948).

[3]County of Allegheny v. ACLU; 106 L. Ed. 2d 472, 550 (1989), Kennedy, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part.

[4]Lee v. Weisman; 120 L. Ed. 2d 467, 516 (1992), Scalia, J., dissenting.

[5]Benjamin Cardozo, The Nature of the Judicial Process (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1921), p. 10.

[6]Charles Evans Hughes, The Autobiographical Notes of Charles Evans Hughes, David J. Danelski and Joseph S. Tulchin, editors (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973), p. 144, speech at Elmira on May 3, 1907.

[7]Boston Gazette, January 20, 1772, Samuel Adams writing as “Candidus.”

[8]Thomas Jefferson, The Writings of Thomas Jefferson (Washington, D. C.: The Thomas Jefferson Memorial Association, 1904), Vol. XV, p. 277, to William Charles Jarvis on September 28, 1820.

[9]A Constitution or Frame of Government Agreed Upon by the Delegates of the People of the State of Massachusetts-Bay (Boston: Benjamin Edes & Sons, 1780), p. 9, Massachusetts, 1780, Part I, Article V.

[10]Jefferson, Writings, Vol. VII, pp. 422-423, to M. L’Abbe Arnoud on July 19, 1789.

[11]James Madison, The Papers of James Madison, Henry D. Gilpin, editor (Washington: Langtree & O’Sullivan, 1840), Vol. II, pp. 1161-1171, Luther Martin at the Constitutional Convention on July 21, 1787.

[12]Joseph Story, Commentaries on the Constitution of the United States (Boston: Hilliard, Gray, and Company, 1833), Vol. II, p. 233, § 760.

[13]Jefferson, Writings, Vol. XV, pp. 213-214, to Judge Spencer Roane on September 6, 1819.

[14]Charles S. Hyneman and George W. Carey, A Second Federalist (1967) supra note 91 at 183-84 (quoting Senator William Giles.

[15]Debates In the Congress of the United States on the Bill for Repealing The Law For the More Convenient Organization of the Courts of the United States; During the First Session of the Seventh Congress (Albany: Collier and Stockwell, 1802), pp. 658-659.

[16]Empire and Nation, Forrest McDonald, editor (Indianapolis, Liberty Fund, 1999), John Dickinson, Letters From a Farmer in Pennsylvania, Letter IX, p.53.

[17]David Barton, Restraining Judicial Activism (Aledo: WallBuilder Press, 2003), p. 10, n. 25, 26.

[18]Story, Commentaries, Vol. II, pp. 233-234, § 762.

[19]The Federalist Papers, #65 by Alexander Hamilton.

[20]Madison, Papers, Vol. III, p. 1528, Elbridge Gerry at the Constitutional Convention on Saturday, September 8, 1787.

[21]William Rawle, A View of the Constitution of the United States of America (Philadelphia: Philip H. Nicklin, 1829), p. 211.

[22]Rawle, View of the Constitution, p. 210.

[23]Story, Commentaries, Vol. II, pp. 256-257, § 788.

[24]John Randolph Tucker, The Constitution of the United States: A Critical Discussion of its Genesis, Development, and Interpretation, Henry St. George Tucker, editor (Chicago: Callaghan & Co., 1899), Vol. I, pp. 411-412, § 199 (f ), p. 415, § 199 (o).

[25]Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution, Jonathan Elliot, editor (Washington: Printed for the Editor, 1836), Vol. IV, p. 32, James Iredell at North Carolina’s Ratification Convention on July 24, 1788.

[26]A Constitution . . . of Massachusetts-Bay, p. 9, Massachusetts, 1780, Part I, Article V.

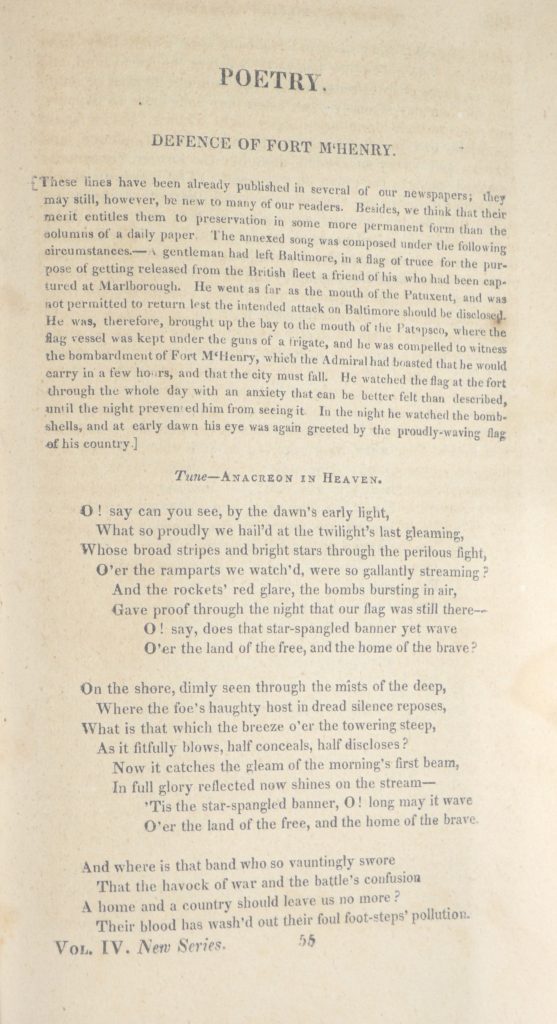

Fort McHenry had been named for Constitution signer James McHenry, who was Secretary of War under both President George Washington and President John Adams. [1] Interestingly, McHenry’s own son John fought as a volunteer in that battle [2] — a battle best known for birthing America’s national anthem: “The Star Spangled Banner.”

Fort McHenry had been named for Constitution signer James McHenry, who was Secretary of War under both President George Washington and President John Adams. [1] Interestingly, McHenry’s own son John fought as a volunteer in that battle [2] — a battle best known for birthing America’s national anthem: “The Star Spangled Banner.”

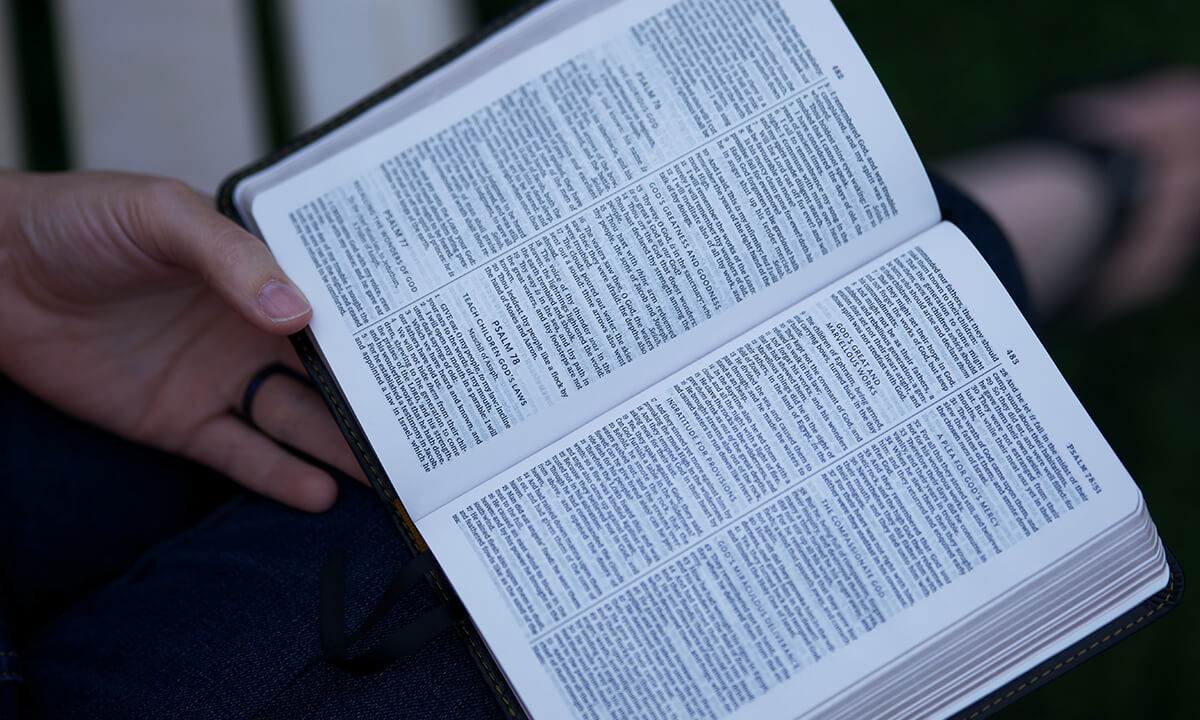

No provision in our Constitution ought to be dearer to man than that which protects the rights of conscience against the enterprises of the civil authority.

No provision in our Constitution ought to be dearer to man than that which protects the rights of conscience against the enterprises of the civil authority.

Princeton was

Princeton was  Harvard University was

Harvard University was

For example, she stressed the importance of Dr. King but apparently did not realize that in his famous “

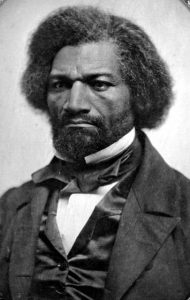

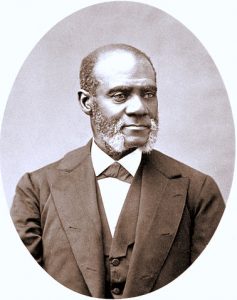

For example, she stressed the importance of Dr. King but apparently did not realize that in his famous “ But Dr. King wasn’t the first black civil rights activist to praise the Declaration of Independence.

But Dr. King wasn’t the first black civil rights activist to praise the Declaration of Independence.  And

And

To contact your Representative or Senator: From a constitutional perspective, it is unconscionable that the current policy penalizing the free speech of religious institutions has remained intact and unchallenged for this long. The government has long recognized that institutions of faith and houses of worship have provided vital services to our communities and our nation. In fact, our public policy has been to honor the valuable contributions of these organizations with an exemption from taxes both for the organizations themselves and for the individuals and groups who support them. Regrettably, because of a simple appropriations rider in 1954, our public policy changed to recognizing the valuable contributions of houses of worship only if they gave up their constitutional right to free speech. (What an amazing exchange: we will honor your charitable contributions but only if you will give up your constitutional rights!) This obviously represents bad public policy and unjustly muzzles thousands of churches across America by preventing them from exercising their fundamental right to free speech. Free speech is most valuable when it is exercised during the elections of our government leaders.

To contact your Representative or Senator: From a constitutional perspective, it is unconscionable that the current policy penalizing the free speech of religious institutions has remained intact and unchallenged for this long. The government has long recognized that institutions of faith and houses of worship have provided vital services to our communities and our nation. In fact, our public policy has been to honor the valuable contributions of these organizations with an exemption from taxes both for the organizations themselves and for the individuals and groups who support them. Regrettably, because of a simple appropriations rider in 1954, our public policy changed to recognizing the valuable contributions of houses of worship only if they gave up their constitutional right to free speech. (What an amazing exchange: we will honor your charitable contributions but only if you will give up your constitutional rights!) This obviously represents bad public policy and unjustly muzzles thousands of churches across America by preventing them from exercising their fundamental right to free speech. Free speech is most valuable when it is exercised during the elections of our government leaders.