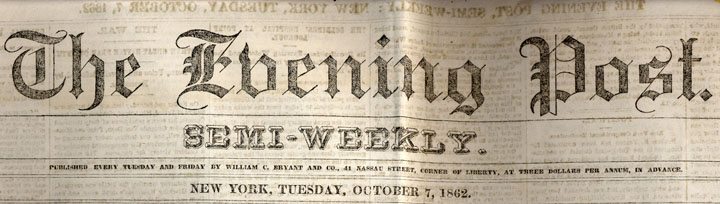

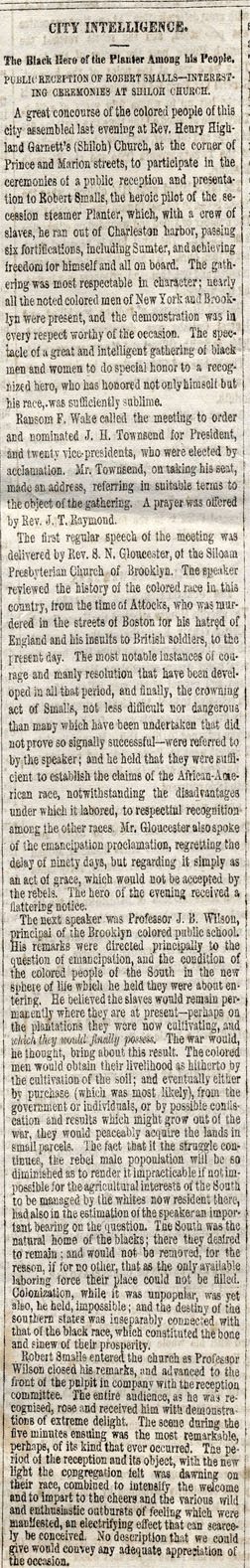

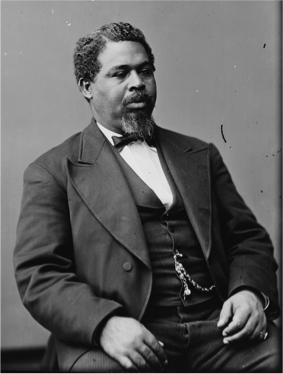

The following newspaper article is about the Gold Medal presented to Robert Smalls. Robert Smalls, a former slave at the time of the printing of this article, was pressed into service in the Confederacy as the quartermaster for the steamer Planter. On May 12, 1862 he was given an opportunity, as a result of the removal of the Confederate officers of the steamer, to take the steamer and make his escape. He piloted the steamer to freedom and surrendered it to the Union. The complete story of his inspiring escape can be found in this WallBuilders Newsletter. The New York newspaper, The Evening Post from October 7, 1862, gives the account of the presentation of Smalls with a Gold Medal from the “colored citizens of New York.”

The Black Hero of the Planter Among His People.

PUBLIC RECEPTION OF ROBERT SMALLS – INTERESTING CEREMONIES AT SHILOH CHURCH

A great concourse of the colored people of this city assembled last evening at Rev. Henry Highland Garnett’s (Shiloh) Church, at the corner of Prince and Marion streets, to participate in the ceremonies of a public reception and presentation to Robert Smalls , the heroic pilot of the secession steamer Planter, which, with a crew of slaves, he ran out of Charleston harbor, passing six fortifications, including Sumter, and achieving freedom for himself and all on board. The gathering was most respectable in character; nearly all the noted colored men of New York and Brooklyn were present, and the demonstration was in every respect worthy of the occasion. The spectacle of a great and intelligent gathering of black men and women to do special honor to a recognized hero, who has honored not only himself but his race, was sufficiently sublime.

A great concourse of the colored people of this city assembled last evening at Rev. Henry Highland Garnett’s (Shiloh) Church, at the corner of Prince and Marion streets, to participate in the ceremonies of a public reception and presentation to Robert Smalls , the heroic pilot of the secession steamer Planter, which, with a crew of slaves, he ran out of Charleston harbor, passing six fortifications, including Sumter, and achieving freedom for himself and all on board. The gathering was most respectable in character; nearly all the noted colored men of New York and Brooklyn were present, and the demonstration was in every respect worthy of the occasion. The spectacle of a great and intelligent gathering of black men and women to do special honor to a recognized hero, who has honored not only himself but his race, was sufficiently sublime.

Ransom F. Wake called the meeting to order and nominated J. H. Townsend for President, and twenty vice-presidents, who were elected by acclamation. Mr. Townsend, on taking his seat, made an address, referring in suitable terms to the object of the gathering. A prayer was offered by the Rev. J. T. Raymond [Pastor of First Independent Baptist Church in Boston].

The first regular speech at the meeting was delivered by Rev. S. N. Gloucester, of the Siloam Presbyterian Church of Brooklyn. The speaker reviewed the history of the colored race in this country, form the time of Attocks {sic}, who was murdered in the streets of Boston for his hatred of England and his insults to British soldiers, to the present day. The most notable instances of courage and many resolution that have been developed in all that period, and finally, the crowning act of Smalls, not less difficult nor dangerous than many which have been undertaken that did not prove so signally successful – were referred to by the speaker; and he held that they were sufficient to establish the claims of the African-American race, notwithstanding the disadvantages under which it labored, to respectful recognition among the other races. Mr. Gloucester also spoke of the emancipation proclamation, regretting the delay of ninety days, but regarding it simply as an act of grace, which would not be accepted by the rebels. The hero of the evening received a flattering notice.

The next speaker was Professor J. B. Wilson, principal of the Brooklyn colored public school. His remarks were directed principally to the question of emancipation, and the condition of the colored people of the South in the new sphere of life which he held they were about entering. He believed the slaves would remain permanently where they are at present – perhaps on the plantations they were now cultivating, and which they would finally possess. The war would, he thought, bring about this result. The colored men would obtain their livelihood as hitherto by the cultivation of the soil; and eventually either by purchase (which was most likely), from the government or individuals, or by possible confiscation and results which might grow out of the war, they would peaceably acquire the lands in small parcels. The fact that if the struggle continues, the rebel male population will be so diminished as to render it impracticable if not impossible for the agricultural interests of the South to be managed by the whites now resident there, had also in the estimation of the speaker an important bearing on the question. The South was the natural home of the blacks; there they desired to remain; and would not be removed, for the reason, if for no other, that as the only available laboring force their place could not be filled. Colonization, while it was unpopular, was yet also, he held, impossible; and the destiny of the southern states was inseparably connected with that of the black race, which constituted the bone and sinew of their prosperity.

The next speaker was Professor J. B. Wilson, principal of the Brooklyn colored public school. His remarks were directed principally to the question of emancipation, and the condition of the colored people of the South in the new sphere of life which he held they were about entering. He believed the slaves would remain permanently where they are at present – perhaps on the plantations they were now cultivating, and which they would finally possess. The war would, he thought, bring about this result. The colored men would obtain their livelihood as hitherto by the cultivation of the soil; and eventually either by purchase (which was most likely), from the government or individuals, or by possible confiscation and results which might grow out of the war, they would peaceably acquire the lands in small parcels. The fact that if the struggle continues, the rebel male population will be so diminished as to render it impracticable if not impossible for the agricultural interests of the South to be managed by the whites now resident there, had also in the estimation of the speaker an important bearing on the question. The South was the natural home of the blacks; there they desired to remain; and would not be removed, for the reason, if for no other, that as the only available laboring force their place could not be filled. Colonization, while it was unpopular, was yet also, he held, impossible; and the destiny of the southern states was inseparably connected with that of the black race, which constituted the bone and sinew of their prosperity.

Robert Smalls entered the church as Professor Wilson closed his remarks and advanced to the front of the pulpit in company with reception committee. The entire audience, as he was recognized, rose and received him with demonstrations of extreme delight. The scene during the five minutes ensuing was the most remarkable, perhaps, of tis kind that ever occurred. The period of the reception and its object, with the new light the congregation felt was dawning on their race, combined to intensify the welcome and to impart to the cheers and various wild and enthusiastic outbursts of feeling which were manifested, an electrifying effect that can scarcely be conceived. No description that we could give would convey any adequate appreciation of the occasion.

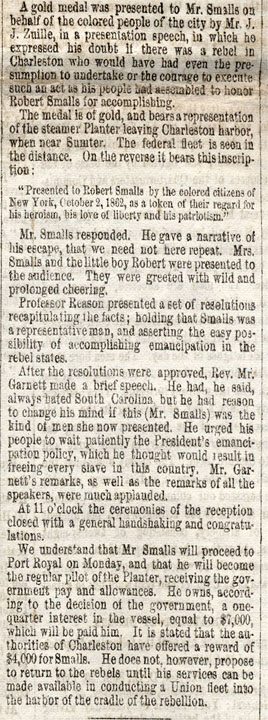

A gold medal was presented to Mr. Smalls on behalf of the colored people of the city by Mr. J. J. Zuille, in a presentation speech, in which he expressed his doubt if there was a rebel in Charleston, who would have had even the presumption to undertake or the courage to execute such an act as his people has assembled to honor Robert Smalls for accomplishing.

A gold medal was presented to Mr. Smalls on behalf of the colored people of the city by Mr. J. J. Zuille, in a presentation speech, in which he expressed his doubt if there was a rebel in Charleston, who would have had even the presumption to undertake or the courage to execute such an act as his people has assembled to honor Robert Smalls for accomplishing.

The medal is of gold, and bears a representation of the steamer Planter leaving Charleston harbor, when near Sumter. The federal fleet is seen in the distance. On the reverse it bears this inscription:

“Presented to Robert Smalls by the colored citizens of New York, October 2, 1862, as a token of their regard for his heroism, his love of liberty and his patriotism.”

Mr. Smalls responded. He gave a narrative of his escape, that we need not here repeat. Mrs. Smalls and the little boy Robert were presented to the audience. They were greeted with wild and prolonged cheering.

Professor Reason presented a set of resolutions recapitulating the facts; holding that Smalls was a representative man, and asserting the easy possibility of accomplishing emancipation in the rebel states.

After the resolutions were approved, Rev. Mr. Garnett made a brief speech. He had, he said, always hated South Caroline, but he had reason to change his mind if this (Mr. Smalls) was the kind of men she now presented. He urged his people to wait patiently the President’s emancipation policy, which he thought would result in freeing every slave in this country. Mr. Garnett’s remarks, as well as the remarks of all the speakers, were much applauded.

At 11 o’clock the ceremonies of the reception closed with a general handshaking and congratulations.

We understood that Mr. Smalls will proceed to Port Royal on Monday, and that he will become the regular pilot of the Planter, receiving the government pay and allowances. He was, according to the decision of the government, a one-quarter interest in the vessel, equal to $7,000 which will be paid him. It is stated that the authorities of Charleston have offered a reward of $4,000 for Smalls. He does not, however, propose to return to the rebels until his services can be made available in conducting a Union fleet into the harbor of the cradle of the rebellion.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!