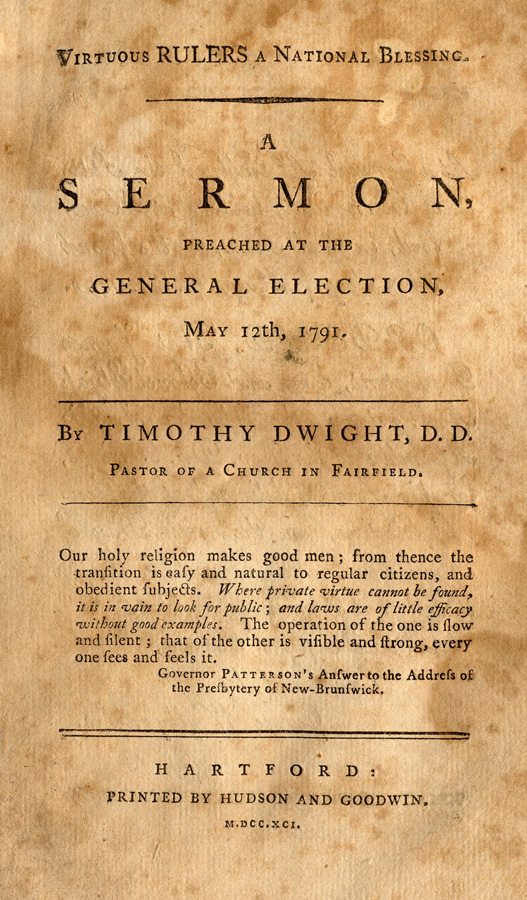

Timothy Dwight (1752-1817) graduated from Yale in 1769. He was principal of the New Haven grammar school (1769-1771) and a tutor at Yale (1771-1777). A lack of chaplains during the Revolutionary War led him to become a preacher and he served as a chaplain in a Connecticut brigade. Dwight served as preacher in neighboring churches in Northampton, MA (1778-1782) and in Fairfield, CT (1783). He also served as president of Yale College (1795-1817). This sermon was preached by Dwight in Connecticut on May 12, 1791.

A

S E R M O N,

PREACHED AT THE

GENERAL ELECTION,

May 12th, 1791.

By TIMOTHY DWIGHT, D. D.

Pastor of a Church in Fairfield.

Our holy religion makes good men; from thence the Transition is easy and natural to regular citizens, and obedient subjects. Where private virtue cannot be found, it is in vain to look for public; and laws are of little efficacy without good examples. The operation of the one is slow and silent; that of the other is visible and strong, everyone sees and feels it.

Governor PATTERSON’S Answer to the Address of the Presbytery of New-Brunswick.

At a General Assembly of the State of Connecticut, holden at Hartford, in said State, on the second Thursday of May, A. D. 1791.

ORDERED, That James Davenport, Esq. and Colonel Elijah Abel, return the Thanks of this Assembly to the Rev. Dr. Dwight, for his Sermon delivered at the General Election, on the 12th Day of May 1791, and request a Copy thereof that it may be printed.

A true Copy of Record,

Examined by

George Wyllys, Sec.

2 SAMUEL, xxiii. 3, 4.

The God of Israel said, the Rock of Israel spake to me, He that ruleth over men must be just, ruling in the fear of God.

And he shall be as the light of the morning, when the sun riseth; even a morning without clouds; as the tender grass springing out of the earth, by clear shining after rain.

When our ancestors instituted the solemnities of this day, they gave the world a fair exhibition of their wisdom and piety. The election of the great officers of a state is an event highly important, and solemn, and ought to be regarded with solemn emotions. To inspire such emotions, they justly determined, nothing would more effectually conduce, than the union of he Legislature in the public reverential acknowledgement of the presence, and agency, of Him, “whose throne is prepared in the heavens, and whose kingdom ruleth over all.” Influenced by that piety, which was their governing characteristic, they were experimentally convinced, that, as no consideration is so interesting, so none is so productive of rectitude, in public, or in private life, as the omnipresence, and omniscience, of that God, to whom we must give an account of all our conduct. Persons of such a character must also have clearly seen, and strongly felt, that pertinent religious discourses, concerning the duties incumbent on rulers, delivered at such a time, could not fail of advantageous effects. From these just and commendable sentiments, the divine service of this anniversary was instituted by our ancestors; and from the same sentiments, it has been uniformly celebrated by their descendants.

The truth of these remarks will, it is presumed, be readily acknowledged, by those at least, whose authority sanctioned, and whose presence countenances, the business of this meeting. With equal readiness will it be acknowledged, that they clearly point out the duty of the preacher. It is visibly his duty to aim at making such impressions on the minds of his audience, as will most effectually accomplish the design of the institution. It is his duty to address his discourse to the peculiar circumstances of those, who summoned him to the employment; and as far as may be, to awaken in them those reflections, which cannot fail to produce, in men of consideration, some desirable consequences.

For about a hundred and thirty years, has this institution existed; and, throughout this long period, wise and virtuous men have annually uttered, from this place, useful truths, and pious exhortations. After the labours of such a train of respectable characters, the present preacher cannot hope to entertain his audience with novelty, or instruction. In the humbler office of a monitor, he may however advantageously remind those, who hear him, of their interest, and duty; and thus may render to them an office of benevolence, eminently necessary to so frail, and so forgetful a being, as man.

To a design of this nature, the passage of scripture mentioned as the theme of the following discourse is an obvious introduction. The sentiments it contains, are of high importance, and unfold their truth, and moment, to the slightest inspection.

In the first of these verses, it is asserted to be the duty of a ruler to be just, and to rule in the fear of God.1 In the second, the beneficent influence of government, formed on these principles, is declared and described in terms of singular force, and unrivalled beauty.

On the first of these assertions, it will be unnecessary to expatiate. Of its truth, there can be neither denial, nor doubt; and of its importance, a brief examination of the second will furnish sufficient evidence. The following observations will therefore be principally confined to this solemn declaration of the God of Israel—That a just and pious Ruler is an eminent blessing to a people. Of this doctrine, the text naturally forms the first illustration.

Perhaps there is not, in the whole sacred volume, a single passage, introduced with such solemnity and magnificence, as the passage before us. It is ushered in by two prefaces; both of them conspiring, in a striking manner, to increase the impression. We are first informed by the recording prophet, that these are the last words of David—his solemn farewell to the great kingdom, he had so long governed; his dying monition to the numerous tribes of future princes, whom, with the eye of prediction, he saw springing from his loins; his final benediction to those unnumbered princes, and nations, for whom, throughout the vast regions, and extended duration, of this world, he knew his instructions would be recorded. That we may feel the weight of this preface, a singular and illustrious character of David is subjoined. “David, the son of Jesse, the man who was raised on high, the anointed of the God of Jacob, the sweet Psalmist of Israel, said,” &c.

Nothing could, with more pertinence, have been prefixed to these remarkable words, by the prophet who has recorded them. From the character of the author they derive the highest human sanction. Selected by the wisdom of Jehovah from the whole Israelitish nation, at the divine command, he ascended the throne. In this dignified station, he gave the clearest proof of the propriety of this providence. His country had, for ages, been involved in the most distressing wars. In a period of the deepest calamity, he assumed the direction of its public affairs, roused its dismayed inhabitants to arms and enterprise, and, in a little time, subdued all the surrounding nations, from the great sea to the river Euphrates. With soldiers, whom he raised, officered, and disciplined, with a heroism and military wisdom wholly unprecedented, and in dangers, difficulties, and distresses, of which there are few examples, he established the most respectable empire, at that time in the world.

For the government of these extensive dominions, he projected, and executed, a series of the wisest military, and political measures. Steadily attentive to all the great objects of policy, he effectually provided for the defense of his kingdom, for the enlargement of commerce, for the improvement of agriculture, for the promotion of useful knowledge, and for the regular administration of justice; and, in all, displayed a strength of genius, and a largeness of heart, to which we shall not easily find a parallel. At the same time, he exhibited an illustrious example of the most distinguished virtue. In his excellent and splendid institutions for the public worship of the nation; in those glorious monuments of genius and piety, those perpetual directories of private and public devotion, the psalms he composed; in the regular, expeditious, and impartial distribution of civil justice; and in the combined beauties of a noble personal example; he gained from the voice of heaven that exalted title, “the man after God’s own heart;” and left his memorial to succeeding ages, as a sweet smelling savour, as an object of the applause, and the imitation, of all who should come after him.

It is further to be remembered, that he was advanced to the kingdom, from the humblest station of private life. Tho’ descended from princes, he was, like the Messiah, whom he principally typified, born, and educated in the vale of poverty. In the condition of a subject, he had seen, and felt, all the evils of unjust and impious rule, exercised by his predecessor. As a subject, he knew how to feel for other subjects; as a man persecuted, for other objects of persecution; while, from his long possession of the sceptre of government, he became extensively acquainted with the art of governing with dignity, and success.

Of such a man, are these the last words, uttered at the close of such a life.

The preface of David is still more solemn, and affecting. “The spirit of the Lord,” saith he, “spake by me, and his word was in my tongue.” That eternal spirit “who searcheth all things, even the deep things of God,” speaks expressly the things, which I now utter, as the sum of his own infinite knowledge of this great subject, and the effusion of his infinite benevolence to the children of men. “The God of Israel said, the Rock of Israel spake to me,” &c. The father of the universe, the ruler of an infinite empire, declares to mankind these counsels, as a general conformity to his pleasure and example; and as the result of his own experience, in the august employment of ruling the immensity of intelligent beings.

Such is the magnificent introduction of this singular passage; and such is the force, with which it is intended to operate on the mind of every reader.

In a manner, perfectly suited to so impressive an exordium, is the doctrine exhibited by the passage itself. And he, i.e. a virtuous ruler, shall be as the light of the morning, when the sun riseth, even a morning without clouds; as the tender grass springing out of the earth, by clear shining after rain. Never were objects of more pleasing and splendid beauty exhibited in comparison; nor could any conceivable images unfold this subject with superior energy. The light of the morning is, without a question, the first object in the natural world, for beauty and glory, and the happiest allusion for the illustration of scenes, marked with unusual gladness, prosperity, and splendor. But it is here enhanced with peculiar felicity. It is not only the morning, but the happiest time of the morning; the time when the sun riseth; it is a morning without clouds; a morning of the spring, when the tender grass is springing out of the earth, and peculiarly endeared by the remembrance of the dreariness of winter; a morning succeeding a night of clouds and rain, and doubly delightful by the contrast it forms, to the melancholy gloom of the preceding darkness. Thus is the general gladness and felicity, produced by the benignant influence of a virtuous ruler, most advantageously impressed on us, by the voice of the infinite God, in the singularly happy allusion to the universal delight, created, thro’ this lower world, by the glorious rising of an unclouded morning in the spring, when a preceding night of rain and darkness has ushered it in with increased beauty and splendor; when the new born and newly freshened verdure has mightily enhanced the general luster of all those pleasing forms of elegance and grandeur, which the day-spring, in the magnificent language of the Creator, has stamped on the face of the earth, turned to the sun, “as clay to a seal,” that it may derive from his power an impression so wonderful and divine.

2. The conduct of a virtuous ruler, both in his public, and in his private character, will also happily illustrate the doctrine.

To form satisfactory ideas of the natural, the necessary conduct of a virtuous ruler, it may be useful to turn our attention, for a moment, to the several principles, under the influence of which, a ruler may be supposed to aim at the public good.

A ruler may be supposed to aim at the public good, from the selfish principles of avarice and ambition; so far as he conceives the public good and his own private interest to be inseparably connected. With what uncertainty and hazard, the welfare of a community is entrusted to men, governed solely by these principles, we may easily determine, by recollecting how often that welfare will be really separated from the private interest of any individual, and how much oftener these things will be viewed as separate, by the selfish affections, and the biased judgment of that individual. If this mode of determining should be thought improper, history, filled with the unnumbered and infinite evils of sceptered ambition, and avarice, will establish the like determination, with an authority, which can neither be gainsayed, nor resisted.

Honour constitutes another basis, on which it has been thought, the public interest might safely rest. Honour, as commonly used, and pride are but different names for the same odious, treacherous, domineering passion. Of its usual and natural effects, we may find an impressive list, in the private history of gambling, lewdness, dueling and suicide; and a more splendid one, in the public annals of imperial luxury, war, and despotism. It is however further to be remarked, that, as honour, in this sense, is wholly governed by a regard to the eye of mankind, so it can have no influence in measures, withdrawn from the inspection of that eye: a class of measures, on which always a great part, and often the whole, of the public good ultimately depends.

But it has been urged, that there is another and superior kind of honour, which, in opposition to the false kind, I have mentioned, is called true honour. This is variously defined. Sometimes it is asserted to be an instinctive and exquisite sensibility to right and wrong, to that which is noble or debased; by which the mind is irresistibly, or at least very forcibly, led to pursue that, which is right and noble, and to shun that which is wrong and debased. Sometimes it is spoken of, as a governing reverence, felt by a man for the approbation of his own mind, and a disposition steadily determined to deserve it. The opinion, contained in the first of these definitions, is fairly presumed to be chimerical; no satisfactory evidence having been hitherto offered, of the existence of such a principle. According to the last, honour will probably be found to differ little from conscientiousness; a principle which I shall now proceed to consider.

The natural conscience, then, carefully cultivated by education into habit, enlivened by a fixed sense of accountableness to God, and strengthened by the belief of future eternal retribution, as revealed in the scriptures of truth, forms another, and it must be confessed, a much more solid foundation, on which to rest the welfare of a community. A habit of conscientiousness is frequently lasting, and frequently extensive in its effects; and the steady belief of a certain, endless retribution, beyond the rave, furnishes a guard against temptation, and iniquity, which is powerful in its operations, and which extends its influence to the closet, as well as to the house top; to the conduct, which no human eye seeth, as well as to that, which is opened to the eye of the world.

But real or scriptural virtue presents us a still different object of public as well as private confidence. The great law of righteousness, by which the Creator requires his intelligent creatures to regulate their affections, is “Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself;” or, as it respects the actions of such creatures, “Whatever ye would that men should do unto you, do ye even so to them.” A cheerful obedience of the heart to this great command, and to that “other, which is like unto it,” is the sum of real, or scriptural virtue.

How fair and sufficient ground of public confidence is displayed by this principle, a few observations will easily illustrate. The governing disposition of a ruler, whose heart is conformed to this great law, must necessarily lead him to a faithful, uniform pursuit of the public interest, in preference to any private one, and to seek the good of millions rather than his own. Between selfish and general objects, as there is in reality, so there will be in his view, no proportion; and between the pleasure of seeking the one, and the duty of promoting the other, he can admit of no balancing. The principle, by which he is rendered the object of the public confidence, is superior to that of the avaricious, and that of the ambitious man, not only because it possesses higher dignity, and amiableness, but also because his interest can never be separated by it from that of the community: to that of the man of honour, because it furnishes a ruling motive to rectitude, in secret, as well as in open measures; and to that of the man habitually conscientious, and possessed of clear conviction of accountableness and retribution, because virtuous habits cannot change; and because, as we daily discern, in the different degrees of obedience, rendered by the dreading servant, and by the affectionate child, love is an incomparably more efficacious spring, than fear, of steady, faithful, and uniform duty.

Under the direction of this principle, the magistracy of a ruler will naturally be such as to secure the approbation of wisdom, and to command the applause of virtue. This all amiable disposition, pointing, with a few variations of human infirmity, to the pole star of public happiness, will direct the extensive means of usefulness, encircled by his office, to the noblest purposes. In the laws he enacts, in the judgments he pronounces, and in the punishments he executes, justice, benignity and mercy will form the great outlines of his character. It will be his natural, his constant labour, so to distribute the burthens of the community, that they will rest most easily on the public shoulder; to husband the public property, with the exactness of private economy; to treat the creditors of his nation with the scrupulous fairness of mercantile punctuality; and to pursue, through all its numerous paths, that righteousness, which nourishes, adorns, and exalts a nation. As a magistrate, he would blush to project, or to countenance, any measure, which would disgrace him as a man. If it were proposed to sanction fraud, to promulgate falsehood, or to establish iniquity, by law, it would present him no temptation, it would yield to him no support, to remember that multitudes, beside himself, were sharers in the guilt and in the infamy.

The first duty of a ruler, and the first concern of a virtuous ruler, is the support of religion. Let not my audience from this remark imagine, that I wish a revival of that motley system of domination which in Europe has so long, so awkwardly, and so unhappily blended civil and spiritual objects. An infidel could not, with more regret, see spiritual courts, laws prescribing faith, binding the conscience, and distinguishing by civil privileges the several classes of religious, or magistrates usurping the throne of the Creator, and claiming the prerogatives of the supreme head of the church. The ruler, who wishes to befriend religion, is forced by no necessity to acts of persecution, injustice, or party; nor because he is desirous of avoiding such acts, is he by any necessity restrained from acting at all. Friendship to religion is the first characteristic of a good man. As such a man must universally desire the good of mankind, so he must, with the greatest ardency, desire this infinite good. That elevation to office, which enlarges the means of doing good, will, in his view, instead of lessening, increase his obligations to “seek first the kingdom of God, its righteousness,” and prosperity. This duty he will endeavour to perform, not in the mistaken ways already mentioned, but by steadfastly opposing immorality, by employing and honouring the just, by contemning the vicious, by enlarging the motives to righteousness, by removing the temptations to sin, and, in a word, by that general train of virtuous measures, which, like a magical charm, unobservedly spreads its influence over moral things, and, in a gloomy waste of vice and impiety, calls up a new creation of beauty, virtue, and happiness.

Among the means of advancing religion, a personal example is commonly of the first importance. Even in private life, its effects are great and striking—In family education, a good parental example instructs more than the wisest precepts, and regulates beyond the best exerted government. But in a ruler, the importance of example is not easily measured. So numerous are the persons, who observe, and imitate his conduct, so distinguished is the brilliancy reflected on it by office, that in forming an idea of its influence, the most romantic imagination will easily fall short of the truth. Strongly affected by the importance of these facts, it will be the daily study of a virtuous ruler, to act always in such a manner, as to allure others to virtue, and not to vice; to uphold religion, and not licentiousness; to support the righteous, and not the enemies of righteousness. Though, during his administration, as at the present time, “iniquity should abound, and the love of many should wax cold” the strength of the opposition, the boldness of the ridicule, and the impudence of the contempt, will instead of relaxing, confirm his resolution, and redouble his efforts against the enemies of religion.

Thus to lessen the public distresses, to increase the public happiness, to discourage vice, to uphold religion, to stand approved at the awful tribunal of his conscience, and to gain the approbation of him, from whose judgment there is no appeal, will be the end of his plans and his exertions, his example and his magistracy.

3. The peculiar power which a virtuous ruler possesses, of being useful to a nation, may also advantageously illustrate the doctrine.

The pertinence of this observation, which is intended principally to be applied to the ruler of a free people, may be exhibited in the following manner. An important part of a ruler’s ability to be useful consists in his influence. The influence of any man depends principally on his personal character. If his actions be such, as to manifest principle, integrity, or virtue, to the general eye, he becomes, of course, possessed of the general confidence. In a country where all measures are decided by suffrages, a fixed belief of the mover’s integrity, and steady patriotism, as often commands those suffrages in favour of the measures, which he proposes, and gives popularity, and efficacy, to the execution of them, as the nature of the measures. Perhaps it is not even a strong assertion, to declare, that the confidence, reposed in the virtue of the first magistrate of this country, has had as much influence, in procuring the general voice in behalf of our national constitution, and in sanctioning its operations, as the nature of the constitution, or the wisdom and justice conspicuous in its operations. As therefore it will frequently happen, that very important public measures will much depend on this confidence, or the want of it, for their adoption, or their rejection, and as the whole wellbeing of a nation may not infrequently be decided by this circumstance, it’s weight cannot fail of a high estimation.

4. In the last place, I shall endeavour to illustrate the doctrine by a summary exhibition of the contrast, formed by a wicked ruler, to a virtuous one.

In all the important particulars, I have mentioned, a wicked ruler is the reverse of a virtuous one. His administration commences under the government of these two noxious principles—That his own highest interest is distinct from that of the public—and that his own interest is, in all things, to be preferred by him to that of the public. Magistracy is, therefore, in his view, but a convenient engine for the accomplishment of his selfish wishes; a courser, put into his hands, merely that he may ride, for business, or for pleasure. From these governing principles are derived all those evils, in public administration, which distract a community from within, or waste it from without. Oppressive laws, partial judgments, and cruel executions; burdensome taxes, and squandered revenues; injurious promotions, causeless ejections from office, neglect of the worthy, and employment of the worthless; caballing, electioneering, and corruption; general sufferings, and general murmurs, are in the number of those evils, which under the magistracy of such a ruler, distress the internal state of a people. It will be needless on this occasion to turn our eyes to the external miseries of war and devastation, naturally springing from the same fountain; war kindled merely to gratify pride, and devastation and rapine extended merely to glut the rapacity of avarice, or cruelty. Our own immediate concern is with the other class of objects; and from his class, I presume, a sufficient selection has been made.

The particular course of wicked conduct, pursued by an unprincipled ruler, will indeed be pointed out by his predominant propensity. As this may happen to be avarice, ambition, sloth, or sensuality, his conduct will be marked by the colouring peculiar to it; or should he, as frequently occurs, be governed by several, or all of them, his magistracy will be tinged by the evil disposition, at the time prevailing; but the tincture will be always deep and poisonous, and the variegations will be only variegations of foulness, guilt, and dishonor.

It has been generally agreed by enlightened men, and even by enlightened infidels and atheists, that religion in a community is essentially necessary to its wellbeing. This agreement may, I presume, be fairly supposed to be a sufficient proof of the justness of the opinion. Should higher proof be demanded, perhaps it may be furnished by a momentary survey of the state of a people, wholly without religion. Think, for a moment only, of a country, inhabited by those, who neither feared God, nor regarded man; by men, insensible to moral obligation, governed by fierce passion, and gross appetite; men of this world merely, unconcerned with truth, or duty, rewards, or punishments; men, strangers to veracity, justice, delicacy, and decency; men, exceptions to the character of human nature, even in the vilest national condition; an astonishment, a byword, and a hissing, to their fellow creatures; a nuisance to the universe, and a smoke in the nostrils of their Creator. On what grounds could the infinitely wise and just God be supposed to continue the existence of such a nation? What valuable end of being could they be supposed to answer?

But if a nation of profligates would be such a blot in the creation of God, let it be uniformly remembered, that a profligate ruler is the first and greatest instrument of national profligacy. That striking and infamous character of Jeroboam, “that he sinned himself, and made Israel to sin,” belongs, as the common sense of mankind, recording with an unerring, and prophetic hand, steadily testifies, to every wicked ruler. Combining in himself the great springs of action, presiding over all the great interests of a nation, directing all it’s great operations, and diffusing a malignant moral influence over all the parts of it, he is at once the moving principle and the regulating power, of the whole machine. Nor can we for a moment hesitate to believe, that, thus moved, and thus regulated, it must be soon disordered, and destroyed.

From the magistracy, and from the example, of such a ruler, alike, will corruption and ruin spread through the members of community, and poison the streams of health and life. Awed by his power, authority, and measures, the friends of virtue are necessitated to hide their heads from shame, insult, and punishment. Called forth, from their lurking places, into office, character, and distinction, “the wicked walk on every side.” Charmed by the splendor of dignity, by the glare of pomp, and by the dazzling effects of influence, all seen with a false deceiving gaudry, by the jaundiced eyes of ambition, the young, the gay, the aspiring, and the brilliant, look up to him, as the standard of excellence, and pant “to be perfect, as he is perfect.” His sentiments are greedily imbibed, his actions anxiously imitated, and his speeches repeated with admiration and applause. Example always powerful, and in a ruler always peculiarly powerful, in a vicious ruler has a redoubled power. The vicious inclinations which are so commonly the governing ones, are peculiarly delighted to see the door to vicious indulgence opened by the example of officed vice, and feel themselves strengthened to every evil pursuit, by the flattering union of wickedness and dignity. Thus is an allurement to depravity and corruption presented to youth, especially to the brightest and most ambitious, against the ruinous effects of which, reason and religion struggle in vain.

Thus all the valuable interests of a nation, the public and the private happiness alike, suffer, from the magistracy of an impious ruler. Law no longer looks with an equal eye on the several classes, and the several concerns, of the nation. Justice weighs, and distributes, with an uneven balance, and suffers that sword which was appointed to be the terror of evil doers, to rust in the scabbard. Religion, opposed by his measures, and discountenanced by his example, languishes and decays. Irreligion, elevated to distinction, and graced by office, impudently lifts up her deformed face, and looks down upon humbled wisdom and piety. The parent trembles for the morals, the character, the salvation of his children; the husband’s heart beats with perpetual alarms, for the fidelity, the honour, and the happiness of his wife; the wife sickens at the changed countenance; and the wife and good man is daily excruciated by the sight of his degenerating friends, and his corrupting country, by the decline of piety and wisdom, by the retreat of truth and salvation.

The several sentiments advanced as illustrations of this interesting doctrine, fraught with truth and evidence in themselves, receive the highest sanction from the inspired declarations. In the 101st Psalm, David, with the voice of truth, beautifully unfolds the proper character of a ruler, in a solemn covenant with his Maker, to “rule in the fear of God.” “I will sing of mercy and judgment, unto thee, O Lord, will I sing. I will behave myself wisely in a perfect way, I will walk within my house with a perfect heart. I will set no wicked thing before mine eyes; a forward heart shall depart from me; I will not know a wicked person. Whoso privily slandereth his neighbour, him will I cut off; him that hath a high look, and a proud heart, will I not suffer. Mine eyes shall dwell upon the faithful of the land, that they may dwell with me; and he that walketh in a perfect way, he shall serve me. He that worketh deceit shall not dwell within my house; he that telleth lies shall not tarry in my sight. I will destroy all the wicked out of the land, that I may cut off all wicked doers from the city of the Lord.” In the 72d Psalm he also exhibits both the character of a virtuous ruler, and the blessings of his government, with that glow of feeling, that splendor of poetry and inspiration, which are not often to be even in his writings, and which prove, at once, the peculiar sincerity of the writer, and on high importance of the subject. In the first nine chapters, and occasionally through the remaining part, of the book of Proverbs, Solomon urges the strictest course of piety, and righteousness, upon his son and successor, with the wisdom of the wisest of men, with the yearnings of a father’s heart, and with the fervor of a man bleeding at every pore, from the remembrance of his own backslidings. In the description of a corrupt and impious prince, given to the Israelites by Samuel, I. Sam. viii. 11, &c. we have one of the many striking pictures, in the Bible, of the odious character, and unspeakable miseries, of unrighteous dominion. To appeal to other passages of either kind will be unnecessary. These prove, beyond dispute, that, 2 ”as a roaring lion, and as a ranging bear, so is a wicked ruler over the poor people;” and that 3 ”the king by judgment” and righteousness “establisheth the land.”

History also yields abundant and unanswerable proof of the doctrine, and of the sentiments, by which it has been illustrated. In the history of the sacred volume, a history, which, beside its unquestionable authenticity, possesses the great advantage of being far better known to every Christian audience, than any other history, and is therefore more happily applied to this design, it seems to have been a principal intention, throughout several books, to exhibit the beneficent influence of virtue, and the malignant influence of vice in rulers. David, Jehoshaphat, Jotham, Hezekiah, Josiah, and Nehemiah, are illustrious examples of virtuous magistracy. The justice with which they governed, the heroism with which they defended, the constancy with which they loved, their people, were glorious proofs of their benevolence. The encouragement which they uniformly gave to the friends of religion, and the opposition they uniformly made to its enemies, by their public conduct and personal example, were equally glorious proofs of their piety. Under their protection, their countenance, their auspicious patronage, piety and righteousness, as in a fruitful soil, cheered by kindly rains, and temperate suns, sprang up, flourished, and yielded a plentiful and most profitable harvest. While the whole earth beside was one gloomy scene of ignorance, violence, and profligacy, the country which they ruled, enjoyed, in a greater degree than could be rationally hoped, peace, liberty, light, and happiness. Tinged they undoubtedly were with human imperfections; but they were yet very fair examples of the amiableness, the excellency, the propitious influence, of “ruling justly, and in the fear of God.”

From our own history, which after that of the scriptures, is better known to us than any other, I might multiply examples, of the like pertinent application. Perhaps no country has enjoyed the government of so many rulers, of distinguished virtue, as this. Our rulers have not only been decent, and unexceptionable, but bold, strenuous, and exemplary, in their virtue. In their public and private conduct, they have fought, and secured, the general prosperity, and caused “the righteous to flourish, with abundance of peace.”

Correspondent with their efforts have been the blessings generally enjoyed. The liberty, the order, the peace, the population, the learning, the piety, of our State have scarcely known an example. No such exhibition has probably been given to the eye of time, of the reign of righteousness; no such specimen of the weight of wisdom and integrity, unclothed with the ensigns of splendor; no such proofs of the happy influence of virtuous rule, since authority first erected her throne among the descendants of Adam.

The minds of all my audience will, almost of necessity, call upon me to produce, on such a list, the name of the first Magistrate of the United States of America. Had not the most evident propriety forced me to mention this great and illustrious person, I would have avoided making an addition to that burden of praise, with which he has been so long distressed. But as there are some persons from whom, on every occasion, infamy instinctively borrows her examples; so to him, with equal spontaneity, commendation always turns her eye, whether she searches for proofs, of private amiableness, or of public dignity and virtue. The application of this example to the doctrine in hand is, in every respect, obvious and striking. All persons must feel, and confess it, who remember, that to the charm of his influence, and to the confidence universally reposed in his integrity and wisdom, the adoption of our national constitution, the peace, the order, and the facility, with which it has begun to operate, and, of consequence, our present union, and all its interesting attendants, are, in a prime measure, to be attributed.

It may also, with the greatest propriety, be observed, that both the countries, from which our historical illustrations have been drawn, have, while thus governed, and thus influenced, been regarded by Heaven, with peculiar favour. That this might be fairly expected, few persons will dispute; and that it took place, with regard to Israel, we are assured by God himself. Concerning our own country, we have not indeed a prophet to testify; but if an uniform experience may be allowed to decide, there will be left little room for doubt. If we remember the blessings, which we have received; if we remember the declarations, on the general subject, in the word of God, if we remember, that the inhabitants, by their suffrages, have ever created their rulers; we shall be easily convinced, that the application of the sentiment is as just, to this country, as to Judea. While, therefore, the steady election of persons, distinguished by virtue, to the first offices of government, reflects the highest glory on the wisdom and integrity of the inhabitants of this State, we have very sufficient reason greatly to attribute, to this conduct, the peculiar favour of Heaven, which we have always enjoyed.

From history, also, we are furnished with the amplest proof, that the operations of wicked magistracy have ever constituted the first class of human evils, and stained the name of man with the deepest infamy. The earth has groaned with the insupportable burthen; time has shuddered to rehearse the tale; and Heaven, as at the deluge, has been often called upon for new feelings of repentance, that man was made. The names of Ahab, Manasseh, Nero, Caligula, Heliogabalus, Mary the 1st, and Charles the 2d, with innumerable others, are a sufficient verification of these remarks; but very page of history, sacred and profane, must be searched, if we would comprehend the height, and the depth, of this vast and humiliating subject.

I have only to observe further, concerning the doctrine, that it is applicable to all rulers, of what office soever, in proportion to the importance of their offices, and the extensiveness of their influence.

Among the several sentiments, naturally deduced from this discourse, two appear to be peculiarly commended to our attention.

1. How illustrious a character is a virtuous ruler.

All things, relating to this subject, unite to unfold, and to complete, the character of a virtuous ruler. The station, to which he is advanced, is the first eminence, beneath the sun. The views, excited by it, in the human mind, are strongly pictured to the eye, by those ensigns of majesty, which have surrounded it, from the beginning; the throne, the crown, the scepter, the pomp of attendance, and the other numerous peculiars of royalty. ON the ear are these views impressed by titles of dignity, of awfulness, of sanctity, of divinity. The services of the body, the treasures of the purse, and the homage of the heart, have conspired to shew, and that, even when mistaken and impious, the sublime ideas, men have instinctively formed of the dignity of a ruler.

The vast means of usefulness, within the limits of superior offices in government, not only render them desirable objects of possession to a person, who wishes to be useful, but exceedingly enhance their importance in the eyes of mankind. The human eye beholds, with the most solemn regard, so much happiness entrusted to the disposal of a single man, such extensive means of doing good attached to a single office, and is instinctively led to form no distant resemblance between him who fills that office, in a manner correspondent with the divine designation, and that glorious Agent, who, in an office infinitely more elevated, “is good, and doth good, and exercises his tender mercies over all his works.” Nor is this resemblance impiously, or irrationally formed. In the language of inspiration itself, we find the name Elokim, one of the titles of divinity, applied to those, who are appointed to be “Ministers of God, for good, to his people.” We can therefore scarcely be surprised, though we may well be displeased, that the mind of man, darkened, as it has generally been, with ignorance and superstition, and disposed, as it has ever been, to carry all its conduct into extremes, should attach to supremacy of dominion some of the attributes of Godhead, and render to the persons of princes that sacred homage, which is due to Jehovah alone.

In the hands of a virtuous ruler, all these materials of dignity, and all these means of usefulness, are presented to the considerate eye, with a peculiar splendor. Such a ruler not only fills the station, which, in this world, is the nearest approach to that infinite station, filled by the Creator; but he also acts the character, which is the nearest resemblance to his. Far from being satisfied with escaping censure, and passing, with quiet decency, through his administration; far from contenting himself with wishing kindly to the public weal, he makes it his prime object, he uses his most strenuous efforts, to promote it. To accomplish extensive good, to make mankind better, and happier, to give confidence to virtue, to trample vice under foot, to extend the kingdom of righteousness, to enlarge the general assembly of the first-born, to increase the glory of the Father, the Redeemer, and the Sanctifier, of man, is his constant, his favourite, his professional employment.

To a serious mind, the character of such a ruler appears invested with singular glory. In the view of such a mind, he stands the vicegerent of Jehovah, appointed to execute the noblest purposes. In the view of such a mind, he is not only elevated to the first earthly distinction, entrusted with the first means of usefulness, and separated from the rest of men by peculiar ensigns of dignity; but, by the voice of God, he is entitled to an unrivalled homage, and secured from opposition, obloquy, and irreverence. A long train of solemn commands, respecting the virtuous ruler alone, and pointed directly to great and general happiness, oblige us to love, to fear, to honor him, with a regard wholly singular, and inferior to that only, which is due to the infinite Ruler. Awful in his station, and amiable in his character, he is justly considered as a fellow-labourer with the Redeemer, in that glorious kingdom of righteousness which he came to establish. Temporal good he steadily promotes, to discharge his duty, to indulge his benevolence, and to furnish daily means of accomplishing eternal good. To him, the support, the reverence, the applause, of wisdom and piety are uniformly given; and servant supplications ascend daily from that great family, of which he is the common parent, that his life may be happy, and that his death may be blessed.

Venerable, however, as this character always is, in this country it is peculiarly venerable. It is here a distinction of reason, and rectitude; an elevation, holding a confessed superiority of intelligence, virtue, and amiableness. A ruler is here the favourite object of the approbation, and the choice, of an immense number of wise and good men. He is singled out from other men, not by conquest, law, or birth; but by the hearts of those, who obey, Free and unsolicited suffrages raise him to office. In the original bond, therefore, by which our society was formed, in the covenant interwoven in the very act of electing, our respect, affection, and allegiance, are pledged to our rulers. Happy in presiding over a people eminently free, enlightened, virtuous, and happy, they are ornamented with distinguished glory, and assured of a most honorary, and to an enlarged mind, a most delightful obedience.

2dly. The preceding observations strongly urge the duty of ruling virtuously.

To impress the importance of this great duty is the principal end for which the preacher was summoned to this place; the first use of this solemn institution. This remark, therefore, cannot be esteemed improper, or unseasonable. Should it be thought unnecessary, a little reflection may perhaps persuade us to adopt a contrary opinion.

It is a humiliating, but just observation, verified by daily experience, that human nature is much more resolute in perpetrating that, which is wrong, than in practicing that, which is right. The friends of virtue are often characteristically distinguished by modesty, and meekness; while the votaries of vice are s often marked by a brazen front, and an overbearing insolence. This calamity, at all times existing, in times of degeneracy is predominant. In such times, vicious men, encouraged by numbers, and feeling bold by increasing example, naturally indulge their hatred to virtue, and throw off that mark of decency, which fear and selfishness have before obliged them to wear. As their audacity gains strength, the confidence of most men’s virtue usually diminishes. When wickedness ascends the throne, when her conduct is fashion, when her voice is law, and her ministers are elders and nobles in the land, those, “who have not bowed the knee to Baal” will be unobserved, and unseen.

In our own country, the present period, tho not a period of the most absolute declension, will yet furnish a ruler sufficient allurements to a lukewarm temper and timid administration. A bold and steady course of virtuous measures will usually produce opposition, and obloquy; and, in a degree, the loss of suffrages, and the loss of reputation. Cabals will undermine, jealousy misconstrue, rivalry misrepresent, and enmity blacken. Thus threatened, alarmed, and wearied, human frailty will be too easily induced to seek the midway, inoffensive course of magistracy: a course, often leading to political safety, but oftener conducting away from duty and righteousness.

But however frequently timidity and indifference may mark the public, or private conduct of those, who act in public offices, it is not because they are not furnished, by Providence, with motives to strenuous virtue, sufficiently numerous, and sufficiently important.

In addition to those, already suggested in this discourse, the remembrance of what has been done, to establish virtue and piety in this land, and of the blessings, which they have produced, presents to the mind one of the most powerful, and interesting. Superior to danger, triumphant over persecution, and glowing with piety, our generous ancestors, that they might leave to their children this best of all legacies, braved every hazard, and overcame every difficulty. Heaven, as if to try, to refine, and to beautify their virtues, to hand down to their descendants a glorious example of meek and matchless fortitude, and to give the world an illustrious pattern of Christianity, “enduring to the end,” led them to seek a refuge in a distant and savage wilderness, summoned the tempest to meet them, on the ocean, and spread want and disease before them, on the land. Chastened, but not forsaken, cast down, but not destroyed, they submitted, yet they endured; they suffered, yet they overcame. Religion was their constant, their angelic guest, a cheering inmate of every dwelling, a divine Paraclete of every heart. This heavenly stranger, since the apostacy of man, and the closure of paradise, had travelled down the gloomy progress of time, and wandered over this inhospitable globe, shut out from the greatest part of human society, and, in most regions, but the guest of a night. Even in Judea, her proper dwelling place, she was often alarmed by violence, and often thrust out by corruption and idolatry; and when the Redeemer of men made that land his earthly residence, though, like him, she went about doing good, yet, like him also, she was shunned, and persecuted, and “had not where to lay her head.” In the company of his apostles, indeed, with the wisdom, strength, and loveliness, which she had derived from his precepts, miracles, and example, she gained a noble, but transient triumph, and saw, with ecstasy, her “still small voice” vanquish, for a season, the sophistry of philosophers, the power of emperors, and the furious persecution of ignorance and idolatry. But her transports were soon to terminate. In the midst of her friends, in the temple where her sacred mysteries were celebrated, arose a new and most terrible enemy, and with “a deadly wound,” pierced her to the heart. After a long and fatal torpor, she was raised, however, as from the grave, by the reforming voice of Zuingle, Calvin, and Luther, lifted up her head with returning strength, and placed her habitation in the western parts of Europe. But, as if warned by a divine premonition of returning licentiousness, with our forefathers she sought out this new world, as a last and permanent asylum. The savage, nursed with blood, and trained up to fraud, revenge, and idolatry, shrunk from her presence. Called into existence, as by a creating voice, towns and villages, schools and churches, rose up in the wilderness and the desert was changed into the garden of God. Let there be peace, she said, and there was peace. She commanded order, liberty, and happiness, to arise, and it was done. The land was no more called desolate; but she named it “Beulah, and Hephzibah,” “an enduring excellency, a joy of many generations.”

By her side, and for her blessings, our progenitors toiled, watched, bled, and died. In their counsels, she animated and presided; in their wars, she inspired and overcame; in their government, she influenced, and blessed; and in their families, she ruled and trained up for endless life.

To watch, to preserve, to extend, to perpetuate this mighty mass of good, earned by our ancestors, and given as an answer to the prayers, and as a reward of the obedience, of piety, is the first duty of every magistrate, minister, and man. Most unnatural children shall we prove, if, with the combined force of so glorious an example, and in the possession of such hard earned happiness, we neglect any means, or refuse any efforts, to discharge this duty.

On the magistrate this burden rests with peculiar weight; for “if the foundations be destroyed, what shall the righteous do?” While, therefore, those of my audience who hold offices of government may, in pursuing this inestimable object, assure themselves of the support and the prayers of the ministers of righteousness, and of all wise and good men, let me, to close with faithfulness the present duties of my office, summarily address to them the solemn motives to virtuous magistracy, suggested by this discourse.

Are you called by the Creator of men, to rule in the several offices of government, let m entreat you to think solemnly of the dignity, the importance, the usefulness of this employment. Remember that it is the noblest of all employments, the first of all the stages of usefulness. Remember that it is a singular honour to be summoned, by God, to the office, and to the power, of doing more good, than other men. Think affectingly, and always, of the inestimable worth of that religion, which the Son of God came from heaven to teach, and to establish which he died on the cross. Often recall to view the illustrious things, which your fathers have done, to leave the invaluable inheritance to you; and think, that your children justly demand of you similar proofs of parental tenderness. Feel, that it is unworthy of the descendants of such ancestors, to tarnish, or even to lessen, that high moral glory, which they attained; and that it is eminently cruel, to deprive your children of the superlative blessings, which those ancestors, with such strenuous duty, such unexampled distresses, such enduring fortitude, purchased for them, as well as for you. Call up into realizing view the glory of making a people virtuous and happy, of promoting the honour and kingdom of Jehovah, and of leaving a name to the affection, the reverence, and the imitation, of succeeding ages. Think of the manner, in which virtuous rulers, who have departed, are loved and mentioned; of the manner, in which you yourselves love and mention them. In all the temptations, dangers, and distresses, which surround you, you will find sufficient consolation, and firm support, in the love of good men, in the applause of conscience, and in the approbation of God. These are satisfactions, of which you cannot fail, independent solaces with which no stranger can meddle, and which worlds and ages cannot diminish. In that solemn period, “when flesh and heart shall fail,” when friends shall retire, and the world recede from your view, when the awakened guilty mind shall open its eyes, with infinite dismay, upon accumulated crimes, surpassing number, and conception, and shrink, with inexpressible amazement, from the approaching sentence of immutable justice, “the rod and the staff” of your Redeemer, your Shepherd, the testimony of a good conscience, the remembrance of so important a stewardship faithfully discharged, the consciousness of having steadfastly done good to your fellow men, “will support and comfort you,” will give you peace in so awful an hour, and firmness in so stupendous a trial. And may He, who holds the hearts of rulers in his hand, and turns them as the rivers of water are turned,” aid you to a faithful discharge of the duties of magistracy, to a fixed reliance on his favour, to a constant fear of his presence, to a steadfast love of mankind, and to a final attainment of the infinite approbation.

Endnotes

1. This passage of scripture has been supposed, perhaps justly, to be a prophecy of the Messiah; according to the following translation—There shall be a ruler over men, a just one, ruling in the fear of God, &c. Should this opinion be adopted, the doctrine may be fairly derived from it. The justice and piety with which it is prophesied, this glorious person shall rule over men, are plainly mentioned, as the reason of that great and general happiness, produced by his government. From the force of the argument, and the dignity of the example, the doctrine receives as high a sanction, as it could receive from any precept.

2. Prov. xxviii. 15.

3. Prov. xxix.4.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!