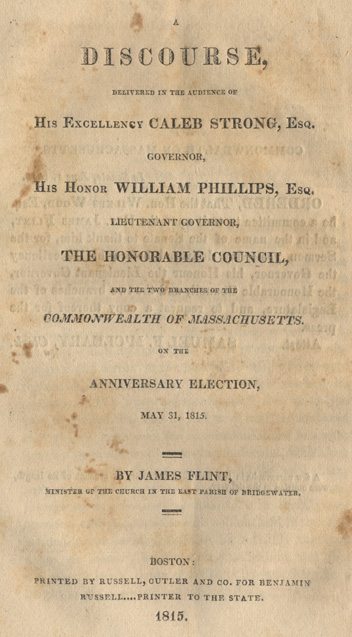

Rev. James Flint preached the following election sermon in Massachusetts on May 31, 1815.

DISCOURSE,

DELIVERED IN THE AUDIENCE OF

HIS EXCELLENCY CALEB STRONG, ESQ.

GOVERNOR,

HIS HONOR WILLIAM PHILLIPS, ESQ.

LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR,

THE HONRABLE COUNCIL,

AND THE TWO BRANCHES OF THE

COMMONWEALTH OF MASSACHUSETTS.

ON THE

ANNIVERSARY ELECTION,

MAY 31, 1815.

BY JAMES FLINT,

Minister of the Church in the East parish of Bridgewater.

Only take heed to thyself, and keep thy soul diligently, lest thou forget the things, which thine eyes have seen, and lest they depart from thy heart all the days of thy life; but teach them thy sons and thy sons’ sons.

Since the last return of this anniversary, the public mind has been agitated by the most affecting alternations of joy and gloom, of awful apprehension and unmingled gladness. We have witnessed, what at the time we deemed the winding up of the great drama, which, for so man years, had been exhibiting in Europe, in which might nations were the actors, and which awakened the most profound commiseration and terror in the bosoms of all, who beheld the novel and stupendous scenes, which marked its progress. We have seen, also – all thanks to the God of our fathers, who in judgment hath remembered mercy – we have seen the conclusion of the less sublime but to us not less interesting under plot, which our own government, in conjunction with the sanguinary hero of the piece, contrived to weave into that drama. Events so astonishing, so important in their consequences, and so pregnant with solemn and instructive lessons to our country, merit to the indelibly engraven upon our memory by frequent recollection, and that we should teach them, “with lessons they have taught us, to our sons and our sons’ sons.”

I would, therefore, ask the attention of my respected auditors to a brief review of these events, of “the things, which our eyes have seen,” – to a cursory notice of some of the important lessons moral and political, which people and rulers, electors and legislators have alike been taught by these things, and are bound to remember; and lastly, to the mention of certain objects, in the promotion of which every patient and philanthropist, and certainly the appointed guardians of a Christian commonwealth, will feel themselves urgently called upon to exert their influence, from the extraordinary character of the times and state of the world, in which we live.

I. A year has not yet elapsed since the friends of liberty, of religion and human happiness in this country, spontaneously and publicly testified their devout and joyous sympathy with the exulting nations of Europe when they heard the tidings of their emancipation from the galling yoke of tyranny, of their delivered from the desolating demon of war, of their restoration to mild and equitable rule, to the quiet cultivation of the arts and enjoyment of the blessings of peace. We had long taken a humane and anxious interest in the great events, that were passing upon the tragic theatre of the old world. We saw, with dismay and deep concern for the liberty, the religion and all the salutary institutions for the improvement and happiness of civilized man, a stern and unrelenting despot, a contemnor of God and man, at the head of a mighty empire, a leader of unnumbered legions trained to the work of destruction in the midst of atheism, carnage and crimes, accustomed to victory, athirst for conquest and plunder, going forth conquering and to conquer. We saw immense armies scattered before him. We saw ancient thrones, principalities and powers fall prostrate at this approach. We saw kings and emperors casting their crowns at his feet. We saw the iron yoke fastened upon the necks of his victims, while terror stifled their groans. We saw him wringing from them, with insatiable cupidity and unsparing cruelty, tribute upon tribute, sacrifice upon sacrifice of their best blood and few remaining comforts; and all this to rivet more firmly the chains, which bound them to the chariot wheels of their conqueror – to satiate his lust of boundless conquest, and to spread the portentous glare, the blasting splendors of his name and despotic communion over the whole civilized world.

We saw, indeed, one people, and one only, who kept the tyrant at bay, who never bowed the knee to this great Baal, who never trembled at “this goals, who then bestrode the” continental “world.” And this people – shall we not exalt in this claim? – this people are our kindred by blood, the descendants of the brethren of our fathers. Their St. George’s channel, their wooden walls and hearts of oak, and more than all, perhaps, the prayers and slams of their “noble army” of Christian philanthropists formed a barrier, which the myrmidons of the tyrant could never pass. England stood unmoved within view of his shores, queen of isles, mistress of the ocean, vanquisher of his fleet and colonies, the asylum of the proscribed objects of his jealousy or revenge, mocking at his important rage, engrossing the commerce of the world, and carrying, in exchange for the perishable products of their soil, the bread of life, the glad tidings of salvation to farthest Indian, and the remotest islands of the Gentiles.

We saw, in the mean time, the despot inflicting upon his passive subjects and allies unheard of hardships and privations by that barbarous engine of tyranny, the continental system, the only weapon with which he could hope to reach that object of his hate and terror, the maritime supremacy of unshaken, undaunted England. The oppression of this system added to others, stamped with the character of the blackest treachery and most outrageous insult, rouse, at length, the slumbering energies of Spain, stirred the proud spirit of Spaniards, and inflamed with a sudden fever of resentment and revenge the blood, which till then they had seems to have forgotten, that they had derived from a brave and warlike ancestry. We saw and admired their desperate daring, their noble struggle. But we rather wished and prayed, than hoped it would be crowned with success, although backed, as it was, with the generous and powerful aid of England. The then little known, but now illustrious Emperor of Russia, finding his empire degraded and burdened by the conditions, which is an unfortunate moment, he had entered into with the mighty oppressor of the continent – convinced, by the fate of neighboring princes, that to be in league with him in any form was to enter into compact for his own destruction, and that his only alternative in order to save anything from the illimitable claims of his imperial friendship, was to hazard every thing in determined hostility against him – warmed also with a generous glow of indignation at oppression, and animated by the heroic example of England and Spain united – above all, elevated and sustained by a pious confidence in God and the justice of his cause – he prepares and calmly waits for the assault, which he was aware had been long mediated by the modern Sennacherib against this crown and empire. We saw that “scourge of God” go forth in his wrath with his hundreds of thousands madly confident of an easy victory over the only remaining empire of the continent, that had courage and strongly to resist his desolating progress to universal dominion.

The prayers of all who cherished in their bosom a spark of interest for the liberty and happiness of mankind, were earnestly preferred dot the righteous Father of the world, that he would interpose. Neighboring and distant nations seemed alike interested, and alike waited the issue of the contest in trembling suspense. Nor were they left long to doubt of the result. For, behold, “the Lord of hosts, mighty in battle, what his glittering sword, and his hand took hold on judgment.” He not only inspired the hardy men of the north, with unconquerable energy and intrepidity in defense of their homes and temples, and of a severing, whom they loved, because they had found in him, not an oppressor, but a father of his people; but he brought, also, to their aid the irresistible might of his ministering servants, the elements, flaming fire and frost, “stormy wind and tempest fulfilling his word.” He scattered by thousands the carcasses of the invaders in the wilderness. He emphatically spoiled the spoilers. And, by a rapid descent from his dizzy eminence, before the close of a second year from his proud entrance into Russia, at the had of perhaps the most powerful and best appointed army the world has yet seen, we saw this disturber and terror of the world reduced to the condition of a despised, and therefore, alas, unguarded exile – the man, whose plans of empire were bounded only by the limits of the earth, restricted to the diminutive island of Elba, –

“The desolator desolate,

“The victor overthrown,

“The arbiter of others’ fate,

“A suppliant for his own,” –

the nations, that he had subdued, restored to their independence, and the calm of peace succeeding to the tempest of war throughout all Europe. This we saw, and as became men we rejoiced; as became Christians we gave glory to God.

But there was much at that time to damp our joy. We had to blush for our country, that it had taken no part in the triumphant cause of God and man. Had taken no part do I say? O blot of infamy, dark eclipse of American glory! Our country did take part in this cause, but it was against it. The only remaining republic upon earth, a nation descended from freemen, whose proudest boast was their hereditary love of liberty, and hatred of tyranny, harnessed themselves to the war chariot of the tyrant, in which he was riding over the necks of prostrate millions. Yes, the exclusive republicans of America voluntarily added themselves to the long list of degraded nations, who were by force leagued with the infidel power of France, against England; and lent, with cordial good will, their utmost aid to beat down that last remaining bulwark in the old world, of rational liberty, and “of the religion which we profess.”

It was soon seen that we must fare, as men, soon or late, must ever fare, who take side with those, who are at strife with God and right and humanity. When the pitying Father of the world opened his ear to the cries of the oppressed nations, when the measure of their chastisement seemed to be full, and he arose to lay aside, with signal dishonor and contempt, though not, as we hoped, forever, the blood steeped instrument of their correction – when the great instigator and patriot of our wicked war thus became, in the view of all, “a thing of naught,” we were left singly exposed to the merited resentment of our enemy, to the pity or derision of the whole world, and probably, if England had insisted, to united hostility of her allies.

Europe rejoiced, and all good men in this country rejoiced to see, in the fallen fortunes of the tyrant, the removal of that example of successful guilt, which had so long emboldened the wicked in every country, and in none, perhaps, more than in this. The central throne of iniquity, infidelity, perfidy and crime seemed to us to be thus overthrown to its base; and we regarded its wide spread ruins, like the traces of the deluge, as a monument to the world of God’s eternal abhorrence of oppressions, violence and blood – as a lesion of awful admonition to all those, who have been abettors or admirers of the French league of atheistic philosophy and hostility against the most sacred principles and institutions, against the most consoling hopes, against, in short, the virtue and happiness of mankind. We considered this league as effectually broken in the overthrow of the despot. In his fall, we saw the head of this serpent bruised. And we rejoiced to see the death wound, as it then appeared, thus inflicted upon the head of the venomous best in Europe extending downwards, till the tail of it, as we may say, which had twined itself about the Genius of America, felt the unexpected stroke, and writhed in sympathetic agony. Divided as it now was, from its head, and but a fragment of the original monster, although like a monster of the polypus species, it continued to retain feebly the power of life and motion, yet it must ere long have perished of itself, had not the imprudent Hercules, that came to our shores to destroy it, in attempting to tear its poisonous folds from the Genius of our republic, unhappily wounded that Genius in the attempt. 1

This touched our pride of country, and awakened in all a determined spirit of resistance, an united zeal to defend our soil and our cities against every attempt of the enemy, to repeat the humiliating scenes which had been exhibited at Washington and Alexandria. Those, who from principle, abhorred the war in its origin, its entire character and conduct hitherto, now, that it had assume da new character, stood ready to repel the foe that should have the temerity to invade the soil, which they had inherited from their fathers, and which had been consecrated by their blood to liberty and independence.

Dreading and preparing for the worst, the people assumed, as one man, a determined attitude of self-defense. While we had nothing to hope from our own government, except that the necessity of making peace must soon grow out of their inability to prosecute the war, we had every thing to apprehend in the approach of the enemy with his whole force, from the natural disposition of man to avenge, when he becomes strong, an injury inflicted on him when he was weak. At the same time, we had something to hope from the moderation, magnanimity, and desire of peace, previously manifested by the nation, with which we were contending, notwithstanding our government had been the assailants in the unrighteous contest.

Such, for some time, had been the state of things, and of men’s minds, in regard to the unnatural and hopeless war in which, while all Europe had rest, we found ourselves involved. And when we recollect the gloomy aspect of affairs in our country, at that time, and the appalling prospects, which were opening before us – the nation without revenue, the treasury empty, public credit gone, the people shrinking from the oppressive burden of taxes, that was lain and coming upon them, many states beginning reluctantly to contemplate temporary separation of their fortunes from those of the general government, as their only security from ruin – all eyes in the mean time, turned with anxious waiting to receive intelligence from our commissioners at Ghent – the thoughts of all recoiling from the distress, the devastation and bloodshed, which must be the result of another season of hostilities, should England determine to prosecute the war with her undivided strength, and with that spirit of resentment and animosity, which the time and circumstances, in which it had been declared by our government, might seem to justify; – already many thousands reduced from competence to poverty, and other thousands with the same disheartening prospects before them; – when we recollect all this, we cannot wonder at the unexampled rejoicings, and the fervor of thanksgiving to Heaven, which the people manifested at the conclusion of a war, which had been waged at incalculable expense without the attainment of a single object, a single claim, for which it was professedly declared. What stronger evidence could we have that the war was no war of the people’s choosing, that in its whole character and in all its aspects, it was odious and had become insupportable to the great mass of the nation, that the almost frantic joy with which the return of peace, of bare peace, without brining with it the shadow of an equivalent for its absence was universally welcomed.

True it is, we saw nothing of this joy – I speak not here of those brave men, who have fronted danger and fought the battles of our defense “by flood or field” and how have covered themselves and their country with all the glory that can be derived from arms; but we saw nothing of this joy, I say, in those sauntering “dogs of war,” who have been distinguished only by wearing about them the badge which showed to what master they belonged, and who heard the tidings of peace, so grateful to the people, with selfish and sullen regret, that they could no longer fee din idleness at the public charge. We saw, indeed, nothing of this joy in the servile pimps an spies of government, who had been thriving upon the distresses of their fellow citizens, and whose occupation and gains were now at an end. We saw nothing of this joy in the many thousand occupants of new offices, which the war had created, those patriotic pensioners upon cabinet patronage, and who, like so many devouring locusts, had overspread the country, and consumed tis resources. But we saw this joy in all its fullness and sincerity, in those private and peaceable citizens, who could gain nothing by the war, who beheld in the peace a limit to those wasteful expenses, of which they must pay their full proportion out of the hard earned fruits of the sweat of their brow; and who, had the war continued, must have presented their own breasts to an invading foe, in place of that defense, which they had a right to demand of the national government, but which had been to the last denied them. We behold this joy in parents, who in another season of hostilities, were anticipating the dreadful spectacle of their sons lying mangled and breathless courses upon the field of battle – in wives, who were foreboding a final adieu from the husband of their youth – in children, who, catching the contagion of their mothers’ fears, beheld the demon of war robbing them of their fathers.

These rejoiced and still rejoice in the event which bade them dismiss their melancholy anticipations, and welcome the heart cheering prospects of quietness in our borders, of returning propriety, of domestic tranquility, and of fathers, husbands, and sons waiting the gentle summons of nature, instead of the abrupt and appalling signal of battle, to resign their spirits to God, who gave them. And in unison with this joy were all the better feelings and sympathies of the human heart. If some dark and perturbed spirits, “who delight in war,” refused to join in the loud chorus of gratulation and gladness, which rang from one extremity of the union to the other, the bright and lovely train of the civil and domestic virtues, the smiling attendants upon peace, were heard mingling their mild voice in the common joy at the return of their long banished patroness and queen. Humanity rejoiced that the earth ceased to be crimsoned with the blood of man, spilt by the hand of his brother; and that the sword was stayed from adding to the number of windows and orphans. Religion, peaceful daughter of heaven, was glad and hymned new anthems of praise to the God of peace, that her voice, which speaks good will toward all men, was no longer to be drowned in the horrid din of battle, in the groans of expiring nature mingling with the savage shouts of victory. Patriotism exulted that our rapid progress to national ruin was arrested and that happier prospects were once more beginning to open upon our suffering country. Justice triumphed in the vanishing of those unholy visions of conquest, which had so long haunted the disordered imagination of our rulers, which had carried fire and sword into so many peaceful villages of Canada, and which have rendered that province the scene of such boundless waste of treasure, of so many signal defeats and disasters, and of one of two splendid and dear bought, but useless victories. In abort, truth, reason, and common sense, so long exiled from the counsels of the nation, hail with gladness this auspicious pause in the reign of delusion, absurdity, restrictive energy, and mad experiment. And who, that loves his country, will not devoutly pray that the pause may be perpetual?

II. From our hasty retrospect of “the things, which our eyes have seen,” we return to notice, as we proposed, some of the important lessons, which we ought to learn form them, and to “teach our sons and our sons’ sons.”

Let the first be lesson of gratitude to the God of our fathers. However ardent, and strong and lasting this gratitude may be, it can hardly equal what we ought to feel for our deliverance from the confusion and ruin, which but recently seemed inevitable, and that we have escaped, with no heavier loss and suffering, great as these have been, from the rash plunge of the nation into the awful perils of war, at a period when the unexampled terrors and miseries of war in Europe solemnly admonished our favored country to remain at peace, and to mitigate, if possible, instead of adding to the woes of an afflicted and bleeding world.

2. We ought, in the next place, to derive new and deeper convictions, from the things we have seen, of the superintending and controlling providence of the Sovereign of the universe, in the direction of human affairs.

In the astonishing change and revolutions, which have marked the age of wonders, in which it is our lot to live, especially in those which have occurred in Europe within the few last years, the supremacy of God, and the agency of his Providence in the government of the world have been so visibly and remarkable manifested, a that even the blind, one would think must see, the hardened feel and be constrained to acknowledge, “that verily there is a God who judgeth in the earth, who enlargeth of straiteneth the nations, who setteth up on end putteth down another, and who doeth all his pleasure among the inhabitants of the earth, as well as among the hosts of heaven.” When we saw the remorseless oppressor of nations ready to take the last step in his march to universal empire, and we were in read lest the whole Christian world must been beneath the sway of an infidel and ferocious despot, with what ease, how speedily, and in a manner how unexpected did God abase to the dust the pride and the might of “the terrible one,” and exalt the weak to the throne of the mighty.

Fear not, then, ye who tremble because the head of the dragon2 is again lifted up. Let him and his angles renew their impious war. The arm of the Almighty hath not waxed feeble. He hath still his Michael and his angles, by whom he hath once given response to the world, and who, when he commissions them, shall again prevail against he dragon; and in the appointed hour, the monster shall be consigned to a safer prison than the islands of Elba.

3. A third lesson, which we have been impressively taught by “the things we have seen,” – and this is another reason for banishing our fears for the result of the renewed contest in Europe – is, that “the triumphing of the wicked is short.” Never, perhaps, since the generation, which God in his wrath swept from the earth with a flood, – never certainly, in any age, or portion of the world that has been shone upon by the blessed lights of Christianity, has there been such a general and open contempt of all religious and moral obligation, such insolent defiance or denial of the divine government and authority, as has been seen in those parts of the old world, which adopted the principles, and afterwards felt the power of revolutionary France. When we saw this colossal power wielded by an individual, “at whose name the world grew pale,” when we saw him successful in all his enterprises of unparalleled daring and guilt, when we saw his humble admirers and obedient followers sitting in the high places of power in our own country, the entire world, to our desponding fears, seems destined by its incensed Creator to fall under the empire of the wicked.

But when they were rearing the last battlements of their Babel, whose impious height had long insulted the Heavens, and from which they began proudly to dictate their laws to the whole earth, we saw their chief in company with numbers of his satellites suddenly hurled from its summit by the hand of retributive justice. We saw him, for a time, and as we hoped forever, left in miserable banishment to “the vultures of his mind,” his own reflections; and like the wretch in the hell of the poet, to admonish by his doom guilty rulers and their adherents in every country to learn righteousness and to fear God. 3 And notwithstanding his unexpected and, wet rust, short reprieve from this doom, it has given us condoling assurance, in which we will rest, that although men without religion, without virtue, without pity or remorse, “join hand in hand,” abuse power, and “frame mischief by a law,” yet shall not the wicked go unpunished. “As a dream, when one awaketh, so, O God, when thou awakest, shalt thou despise their image. And the righteous shall rejoice, when he seeth the vengeance.”

4. We have, again, been taught, what indeed was foreseen by the considerate and has now been made manifest to all by our ill-fated war, that our form of government, our institutions and habits, disqualify us for engaging in wars of conquest. Events have shown that the attack made upon Canada was as impolitic, as it was cruel and wicked. The crying sin of blood-guiltiness was strictly chargeable, in the view of all men of Christian feelings, upon the authors of that measure; to the honor of New England, it will be remembered that by a large majority of its inhabitants, the measure was regarded in the light of an unprovoked and murderous assault upon peaceable and unoffending neighbors. Nor ought it ever to be forgotten by us, or “our sons, or sons’ sons,” that while the war was thus entirely offensive, a war for conquest, and consequently unjust, God was against us; and we accordingly met only with defeat, disaster, and disgrace. But the moment the character of the war was changed, and become a war of defense, and therefore just, God was with us; and, in every instance of importance, except in the attack of the enemy upon the immediate seat and citadel of improvidence and imbecility, the head quarters of the redoubtable heroes of Bladensburg, we were successful in repelling invasion.

5. This nation, moreover, in addition to the innumerable lessons that have gone before in past ages, have received another, and a very serious one, from the things they have recently seen and suffered, upon that inherent vice and ultimate destruction of all republics, party spirit – a blind devotion of the people to the men, who, to obtain office and power, inflame their passion, and flatter their prejudices and pride of opinion. The people of this country have been taught by bitter and costly experiment, to what evils the indulgence of these passion, these prejudices and this pride of opinion may lead. They have seen for what purposes their antipathies to one nation, and attachment to another have been so industriously cherished by incessantly proclaiming and exaggerating the injuries of the one, and anxiously concealing or excusing those of the other. They have seen that their flatters, and the fermenters of strife and war, have achieved nothing for their country, which they promised – have obtained no security against the violation of “trade and sailors’ rights” and while they have been enjoying the emoluments and honors of office, the people have deprived from their counsels no other fruits than general embarrassment and distress, loss of public and private property, and an entail of taxes, which neither they nor “their sons, nor sons’ sons” will probably see cancelled. The people must, we think, have been feelingly persuaded of the truth of the remark long since made, that “party is the madness of many, for the gain of a few.” We trust that the lessons upon this point, so dearly purchased, will not be lost upon the citizens, who have to pay for it; and that they will learn from it to judge of political as they do of religious profession, by its fruits – to distinguish the true friends and able guides of their country from the smooth and fawning pretender to patriotism and disinterested love for the dear people; and, in future, to trust with office those men only, whose known principles and tried virtues entitle them to the public confidence. To have been once deceived by men who promised fair, proves only that we charitable believed them honest and were mistaken. “But when men,” says an eminent statesman, 4 “whom we know to be wicked, impose upon us, we are something worse than dupes. When we know them, then their fair pretenses become new motives for distrust.”

Tempests, engendered in the natural world, by a foul and heated atmosphere, if they sometimes destroy the fruits of the field and the labors of man, are usually succeeded by a purer air, and a brighter day. Noxious insects, pestilent vapors, and obscuring mists, are dispersed. Objects are seen through a clearer medium, and in a new light; and more distinct and correct impressions of them are conveyed to the mind. We will hope that, in like manner, the tempest and fury of the passion, that have been excited among us, and the storms of war produced by them, now that they are spent and gone by, will be followed by moral and political consequences equally salutary and beneficial to our country. And, great as have been the gloom, and distress, and ruin, which have marked their course, we might pronounce the evil incurred small, compared with the good obtained, should we find that they have also swept away, and that forever, “the refuges of lies,” by which an abused people heave been made the victims of series of oppressive and calamitous measures, the effects of which will be felt long after the present generation shall have passed away.

As it is from experience and by sober reflection upon event, that nations as well as individuals learn wisdom, it is, therefore, the bounded duty of the citizens of our republic not only that they retain in remembrance and meditate much and often upon the things they have witnessed and endured for the last few eventful years, that, soberly viewing the causes and pondering the consequences of these things, they may gather from them the instructive lessons we have noticed and others equally obvious and important; but they are bound also to teach them to their children and to warn them of the dangers to which their prosperity and liberties will ever be exposed, from the arts of ambitious and corrupt men and from their own passions and prejudices.

God, by his servant Moses, enjoined it upon the Israelites, as in our text, to be ever mindful of the astonishing events which they had witnessed alike in their deliverances and their chastisements. They were commanded to teach them to their children, “to their sons’ sons,” that the salutary lessons which they inculcated might be transmitted and perpetuated among them. And it is from what others or themselves have experienced, from recollection of their errors and miscarriages, and reflection upon their causes and consequences that men are admonished, instructed and disciplined into prudence and virtue. This is the great end of God’s various dealings with individuals and nations. For this, history unrolls her faithful records. For this, the faculties of memory and reflection hold so distinguished a place in the endowments of the mind. To consign to oblivion, therefore, when they are past, evens, which deeply affected us while passing – to forget our calamities when they are removed and to avert the attention form the true causes and immediate authors of them or to attribute them to false causes or imaginary instruments, is “to despise reproof and to hate instruction;” is not only, like obstinate children, to suffer the infliction of the rod without deriving from it any equivalent for the smart, but is also to invite a repetition of its strokes.

Surely then, it is not expecting too much from the good sense and calculating character of our fellow citizens that they will divest themselves of the unreasonable prejudices, and attachments of party, the immediate or remote cause of most of the evils they have suffered – that they will turn from their political idols whom they have found to be “vanity and a lie,” to the men under whose auspices they were once prosperous and happy; and that they will yet furnish a refutation of that severe maxim of the statesman before cited, that “the credulity of dupes is as inexhaustible as the invention of knaves.”

III. I hasten in the last place to name to my indulgent auditors – for time will hardly permit me to do more – certain objects, in the promotion of which every patriot and philanthropist, and certainly the appointed guardians of a Christian commonwealth, will feel themselves urgently called upon to exert their influence from the extraordinary character of the times and state of the world in which we live.

1. The passing age has been remarkable for its wild speculations, extravagant theories and daring experiments in government, in morals and religion. The people in our own country, as well as in others, have been taught new doctrines upon these subjects – doctrines sanctioned no more by the sober conclusions of reason than by the voice of experience. Their tendency has been to inflate the minds of the uninformed with an overweening sense of their own lights, of their own important – to weaken their respect for the sound maxims, the salutary principles and usages of our fathers – to loosen and in to many instances, to sever the sacred bonds which bind man in allegiance to his God, in equity and in love to his neighbor, his country and his kind. The effects have been answerable – such as we have witnessed have felt and deplored. The order, virtue, happiness, and stability of our republic have been sensibly impaired – its very existence endangered. To remedy these evils if possible, to repair these breaches will be regarded by every good citizen and magistrate as an object of the first importance. And, if this is ever to be affected in any good degree, it must be brought to pass by the same means by which our fathers founded and built up the social edifice which they left to us strong and beautiful, and taught us by their example how to preserve and enjoy.

They were well aware that no free government could be long supported but by the united influence of knowledge, and virtue and the fear of the Lord generally diffused throughout the great body of the citizens. To promote, maintain, and extend the influence of these qualities they bent all the energies of their powerful minds. To this end looked all their public institutions and laws, all their instructions in the pulpit, the college, the school, and in families – those natural seminaries which under Christian parents are of all others foremost in importance as they are in order, in forming the human mind in imbuing it with pious sentiment and virtuous principle.

In order, then, that our free and equal forms of government, our invaluable institutions and usages may recover of the shocks and long survive the changes which they have recited from the licentious and innovating spirit of the age, the united and persevering exertions of the wise and good in every station, aided as far as may be, by the influence of legislative authority, must be strenuously employed to bring back the people to “the old paths and good ways,” in which our fathers walked – to re-establish the authority of the plain and sure maxims, and to put in more general and vigorous operation those tried and effectual means of diffusing knowledge, virtue, and piety, by which the sons of the Pilgrims that have preceded us, formed of New England “a mountain of holiness, a habitation of whatsoever things are true, honest, just pure, lovely, and of good report.”

Knowing therefore the conditions upon which alone the prosperity and permanency of our republican institutions can be insured, the genuine patriot, whether acting in a private or official capacity, will feel himself bound as he would secure, and transmit to his children the rich privileges which he has inherited from his fathers, to exert his utmost ability and influence to enlighten public opinion, to correct and elevate the public morals, to foster the interests and extend the influence of useful learning and pure religion.

2. I would name another object, which is beginning to excite much attention among the reflecting and benevolent in our own country, which is of universal interest to mankind, and in the prominent of which legislators and rulers might, if disposed, do a great deal. The object is no other than to do something, if possible, to bring into discredit and disuse the barbarous and horrible practice of determining national differences by the sword. I know that a proposition of an attempt to abolish wars will be though by many a proof of little else than of a good natured madness in the proposer. But by Christians it ought to be heard with respect and a readiness to cooperate in any measure that may tend to a “consummation so devoutly to be wished” by all the friends of humanity. Surely, our religion gives no countenance to wars, scarcely of defense, and in no case to offensive wars. If wars, as we know from the sure word of prophecy they will, are one day to “cease to the ends of the earth,” how is this great change in the world to be accomplished? Not, we have all reason to think, by miracle, and at once, but gradually, by the combined influence and agency of Christian principles and Christian societies formed for this very end. Traffic in slaves, not long since, was as universally tolerated, as war. But Christian philanthropy and Christian perseverance have already done much and are still going on prosperously to complete the extermination of this infamous practice from out of the limits of Christendom. Were a combination formed in this country, in this state, of the friends of human happiness, aided by legislative concurrence and authority, and let them make their appeals to Christians everywhere, to cooperate in their attempts to impress all hearts which they can influence with abhorrence of the savage customs of war; and perhaps, in tie, by the blessing of God upon their benevolent exertions, the Christian world may owe as much to a New England Association for the abolition of wars, as Africa does to the bond of British philanthropists who led the way in the abolition of the inhuman traffic in slaves. There never was a time more favorable than the present for an attempt of this kind. Should the peace of Europe be speedily re-established by the fall of the outlaw, who hath broken it, as we devoutly hope, government and people, exhausted with the waste and smarting with the wounds of war, will be universally in a condition to listen to an appeal made to their interests and feelings upon this subject. 5 We may at least calculate with assurance, that the legislature of this, and we trust of the other states of the union, will persevere in their endeavors to obtain the constitutional security recommended by the late New England convention, against a repetition of an offensive war, like that from which we have recently escaped.

3. Indulge me in the mention of one object more which merits even more than all the extraordinary interest and exertions which it has so generally produced in the Christian world, and which of all others will, perhaps, be eventually found the most efficient means of accomplishing the object last mentioned, I mean the diffusion of the Holy Scriptures.

Although we doubt not the glorious work will proceed effectually in the hands of the societies and individuals engaged in it, et I would respectfully ask whether it be not an object deserving the liberal patronage of legislative bodies. While this patronage would ensure to these bodies the augmented respect and confidence of their pious constituents, would it not contribute to awaken a more general attention throughout the community to that Sacred volume, which should appear as thus it would, to be an object of peculiar esteem and reverence to the highest order of men in the state? Every friend of Zion, every Christian philanthropist, whose heart glows with the benevolent desire and daily breathes to Heaven the fervent prayer that the kingdom of Christ that blessed empire of light and love, of righteousness and peace, may be extend and established throughout the world and built up in all hearts, must have witnessed with holy joy and exultation the wide spread and still extending triumphs of British charity in the distribution of “the words of eternal life” in all ands and in all languages. What fountains of consolation have thus been opened to the poor and afflicted in those countries which have been swept with the desolating tempests of war? While a night of double darkness, of infidelity and gloomy despotism was brooding over the fairest portion of continental Europe, form the Bible societies in England, the sun of righteousness seemed to arise with new brightness and healing in his beams. In that fortunate isle, while the upas of atheism, rooted and nurtured in France, was spreading wide its baleful shade, dripping with poison to the souls and destruction to the bodies of men, we have seen the tree of life flourishing with unexampled luxuriance, reaching forth its branches and expanding its leaves for shelter and for medicine to the weary and bruised nations. We have shown that we can vie with the men of that illustrious land of our ancestors in wielding the weapons of death and in managing the engines of destruction. Let us emulate them in their more noble and Godlike efforts to save, to enlighten, to console mankind. When appointed to this service it was my pleasing hope that I might be permitted to congratulate my fellow citizens upon the established repose of Europe, as well as of our own country. But the unsearchable counsels of God have appointed otherwise. While we almost imagine that we heard resounding through the world the echoes of the angelic song, which once announced from Heaven peace on earth and good will to men, the terrific genius of destruction again welcomed into fickle and perfidious France, startled us with new alarms of war. Again,

“Red battle stamps his foot and nations feel the shock.”

It is not for us to penetrate or arraign the purpose of God in suffering this. He governs the world; the wrath and crimes of no created being can pass the bounds which he assigns. Confiding in his goodness, it becomes us to submit with silent reverence to what we cannot comprehend. While we sympathize with Europe again convulsed and bleeding, let it renew our gratitude to that kind Providence which hath made us to differ. And God, of his mercy, make us wise to preserve and worthy to enjoy, this distinction, till it is lost in the universal and permanent repose of the world.

Your Excellency, during “the troublesome times” we have seen has given your constituents a decisive and endearing proof that your heart corresponds to this wish in the spirit of a sincere disciple of the Prince of Peace, with the feelings of a lover of his country and of his kind. So long as we remember “the things which our eyes have seen” will not forget but will teach it to “our sons and our sons’ sons” what we owe to this guide who, under God, hath conducted the people and guarded their rights with a wise and paternal vigilance through all the perils that have encompassed them. If Your Excellency has had no part nor lot in the glory of those magistrates who have sent their citizens to gather laurels and to find the cypress in the wilds of Canada, Your Excellency has that which will be far more soothing in the silent and solitary house of life and its close that which is far more illustrious in the esteem of the wise and good, the glory of having sanctioned no measures that have carried mourning and distress into the dwelling of a single family in the state.

In ancient Rome, he that in battle had saved the life of a citizen was rewarded with a civic crown and was honored as a father by the person preserved. The citizens of this Commonwealth between whom and the deadly contagion of a camp and the weapons of an invaded people, Your Excellency has effectually interposed the shield of the Constitution have no civic crowns to give. But they have repeatedly given the highest mark they have to give of their gratitude and respect; and the same time they acknowledge, in each repeated acceptance of it, a new obligation conferred by Your Excellency upon themselves.

The Christian patriot derives his first best earthly reward from the consciousness of upright intention in the discharge of every trust reposed in him by his fellow citizens; the next, from seeing them manifestly benefited by his services; and next to this, form the uniform and often repeated proofs of their cordial attachment and confidence. His last exceeding great reward, to which he steadily but humbly looks is that transporting eulogium form his final Judge, “well done, good and faithful servant; enter thou into the joy of the Lord.”

Your Honor will accept our respectful congratulants upon being again called to fill the office of Second Magistrate in the Commonwealth; and upon which is far more grateful to your Honor, the reviving prosperity of our country which promises to the benevolent increased means of experiencing what your Honor so well knows, “how much more blessed it is to give, than to receive.”

Counsellors, Senators, and Representatives of the Commonwealth; we rejoice with you that the new political year is ushered in with so much happier auspices than the last. You will not need that I should remind you of the high and solemn responsibility which rests upon you in your official character. No one, surely, of your honorable body, can have received the trust reposed in him by his constituents, without feeling the importance, not of the honor, but of the duties attached to it. Least of all should we suppose it possible for a man to take this trust lightly upon him, when an impression of the calamities, which an abuse of it may bring upon his country is so fresh and deep in his mind, as it must be in the mind of every man who remembers what he has recently seen and felt.

Bringing with you, to the counsels of the state, this impression, you will give your sanction to not measures affecting the common interests of your constituents, till looking as far into all their bearings and issues, as the ken of human foresight, assisted by the lights of experience and reason is permitted to penetrate, you conscientiously believe them to be good and salutary. When entered upon the exercise of your legislative functions, you will feel yourselves to be standing upon holy ground. You will, therefore, as becomes the place and your character put off and remove far from your minds, the narrow prejudices and blinding passions of party, the sordid considerations of private interest or personal ambition, as most unworthy to enter into those solemn deliberations and decrees on which depend, in no small degree, the order, security, and prosperity of the Commonwealth.

We may confidently expect from the civil fathers and guardians of the state, all that can be done by legislative authority alone, or in concurrence with the exertions of societies or individuals, to aid the great interests of humanity, to enlighten public sentiment, to improve the public morals, to preserve and increase, in the public mind, a reverence for the name, the word, the Sabbaths, and worship of God, to invigorate and extend the influence of our inestimable civil, literary, and religious institutions.

In all your labors for the promotion of these most important objects, we, the ministering servants of God, are by our office, and form the nature of our charge when faithful to it, “fellow-workers together with you.” We have, therefore, a claim upon your countenance and support, so long as we quit not our sphere. And, if you sometimes find a brother among you, and concern for his flock prompt the question, once put by Eliab to the shepherd, son of Jesse, “Why hast thou come down hither? And with whom hast thou left those few sheep in the wilderness?” Add not, we beseech you, the uncharitable charge laid by the churlish Eliab to his brother, “I know thy pride, and the naughtiness of thy heart; for thou art come down that thou mightiest see,” and mingle in “the battle of contentious partisans.” Your honorable body will rather impute to him a generous zeal to aid you in promoting the great interests of our common Christianity. At least, let the presence of our brethren serve to remind you, that these interests are intimately connected with the great interests of all the state and of our country – that however excellent our constitution and laws, there can be no permanent order, security, or happiness in our republic, unless the citizens composing it are, generally, influenced by the awful sanctions of religion, the hopes and fears of eternity.

Confiding in the wisdom of your counsels in the integrity and patriotism of your intentions, in your zeal for the common welfare not doubting that you will act under a just sense of your accountability to your constituents, and, we trust, to the Searcher of Hearts, we bid you God, speed in the duties before you. May you honorable acquit yourselves, respected Rulers, of your allotted parts in the accomplishment of those high destinies, to which, we trust, it was in the counsels of God to raise this nation, when we planted our fathers in this good land. And while we hail it, as an omen of better days to our country, that so many of our brethren in various parts of the union misled by the false lights of the age, are retuning to the sound maxims of policy and of morals, exemplified and bequeathed to them by the Father of our Republic, we will hope that its glory, emerging like the sun from the clouds that have transiently obscured the brightness of its morning’s rise will hold on its way, like that luminary, with increasing splendor, till it reaches the western ocean, emitting its wildest blaze of effulgence, the moment it touches the waves.

Endnotes

1. The destruction by the British cruisers of our fishing-craft, and o four dismantled coasting the merchant vessels, in our small harbors, laying defenseless towns, and even salt works under contributions, especially the burning of the public buildings at Washington, excited a very general indignation in all parties. And Mr. Randolph has asserted, and probably with reason, that, but for these glaring acts of indiscretion in the enemy, “nothing could have sustained Mr. Madison after the disgraceful affair at Washington. The public indignation would have overwhelmed, in one common ruin, himself and his hireling newspapers.”

Mr. Randolph’s Letter to Mr. Lloyd.

2. Rev. 12 ch. 7 ver. & c.

3. “Phlegyas que misserimus omnes

Admonet, et magna testator voce per umbras:

Discite justiniam moniti, et non temnere Divos.”

Virg. Aen. Lib. 6, ver. 618, & c.

4. Mr. Burke.

5. See an excellent pamphlet upon this subject, entitled “A Solemn Review of the Custom of War,” & c.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

More Resources

Know the Truth and Protect Your Freedoms.

Still looking for answers? Visit our FAQ page

Stay Informed with the Latest Resources

Enter your email address to receive our regular newsletter, with important information and updates right in your inbox!